Anita Loos’s best-selling 1925 novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes has been all but eclipsed by the voluptuous shadow of Marilyn Monroe. Any text would have trouble competing with Monroe’s spun-sugar hair, bursting bodice, and slick lipstick pout in Howard Hawks’s 1953 film adaptation of the novel. In its own time, however, few other popular novels received as much attention from both general readers and cultural critics of note. Well into the 1930s and 1940s, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes had considerable cultural traction and was adapted to nearly every medium imaginable—magazine, stage play, silent film, musical, sound film, comic strip, dress fabric, and wallpaper.1 While the novel’s superficial signifiers (champagne, diamonds, and dancing vamps) could be captured on film or paper a room, its most important characteristic, its voice, was paradoxically silenced with the coming of the sound film. This is particularly striking given that Loos’s novel is fashioned from a convergence of literature and film.

The narrator of Blondes is Lorelei Lee, a gold-digging ditz who spends most of her time wheedling jewelry out of her paramours, shopping, dining at fashionable clubs, or lounging in her “negligay.” Lorelei is a sybarite who, when traveling in France with her sugar daddy, “Gus Eisman the Button King,” and her sardonic best friend, Dorothy, frets that she cannot “tell how much francs is in money,” but decides that “Paris is devine” when she sees “famous historical names, like Coty and Cartier” along with the “Eyefull Tower.”2 She begins keeping a diary when one of her admirers urges her to put her thoughts down on paper. “It would be strange if I turn out to be an authoress,” she muses. “I mean I simply could not sit for hours and hours at a time practising for the sake of a career. … But writing is different because you do not have to learn or practise” (B, 4–5). Although writing appeals to Lorelei, she confides, “the only career I would like to be besides an authoress is a cinema star” (B, 6).

Critics of Blondes, from its initial appearance to now, have taken their cue from Lorelei’s two aspirations (cinema and literature) and have tried to place the novel in the cultural spectrum from mass culture to modernism. Lawrence yoked “Blondes Prefer Gentlemen” and The Sheik together as the kind of best-seller that was beneath him.3 For Q. D. Leavis, Cyril Connolly, and Wyndham Lewis, Blondes epitomized popular culture’s frivolity and idioms of idiocy. However, James Joyce, H. L. Mencken, Aldous Huxley, William Empson, George Santayana, Edith Wharton, and William Faulkner were positively giddy in their embrace of the novel. Mencken, Loos’s friend, whose predilection for dim-witted platinum beauties was said to have inspired Blondes, wrote in a review, “This gay book has filled me with uproarious and salubrious mirth. It is farce—but farce full of shrewd observation and devastating irony” (B, xi). Others who had no personal connection to Loos at the time were similarly enthralled. Huxley wrote that he was “enraptured by the book.”4 In 1926, Joyce wrote to Harriet Shaw Weaver that he had been “reclining on a sofa and reading Gentlemen Prefer Blondes for three whole days,” an image that figuratively reverses Eve Arnold’s 1955 photograph of Monroe in a bathing suit reading Ulysses.5 Recently, some critics have attempted to locate Blondes within paradigms of modernism.6 In fact, it makes more sense to view it as anticipatory of the aesthetic developments later in the century.

Loos’s “Blonde book,” as Faulkner called it, has proven tricky to categorize. As Faye Hammill points out, “The primary difference between the admiring and the critical readers of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is that the former consider Loos as an ironic and perceptive commentator on mass culture and the latter see her as an emanation from that culture and a producer of its commodities.”7 Hammill proposes that “middlebrow” is a useful term to describe Loos’s writing, which responds parodically to both modernist and mass culture. Rather than perpetuating the battle of the brows, I suggest that the significance of Loos’s work lies not in its adherence to existing literary paradigms, but rather in its creation of a distinct style that incorporates the kinds of linguistic projects modernism cast as unpleasure into a more buoyant form of vernacular textuality.

Lorelei’s blonde “ambishion” of intertwining literature and cinema unwittingly reflects Loos’s development of a literary style that had affinities to some of the most radical aesthetic projects of early twentieth-century art from within popular culture. Loos herself was a star “authoress” of cinema, having written over a hundred one-and two-reelers, along with features for Douglas Fairbanks and D. W. Griffith, two pillars of American filmmaking, and screenplays such as Red-Headed Woman (1932) and the adaptation of Clare Booth Luce’s The Women (1939). There has been a recent resurgence of interest in Loos, signaled by a series of trenchant articles on Blondes and by Anita Loos Rediscovered, which presents a selection of her extensive cinema writing.8 During the silent era, Loos was widely known as one of the most innovative writers of titles (variously called intertitles, subtitles, or leaders). Her contributions to cinema and literary history have only recently begun to be formally connected.

Film historians have presented the main story of early cinema as the controversy about the coming of sound, but there was also a passionate debate about titling, and Loos was an important part of this. Challenging the separation of literature and cinema as high and low culture, Loos develops a mode of writing in which literature and cinema together unmoor the conventional relationship of the image to the word. In both media, words exceed their contexts and signify not only through their meaning but also through their literal status as objects: letters printed on the page or projected on the screen. As Brooks E. Hefner points out, Loos inaugurated a “new way of thinking about how film relates to modernist modes of fictional representation and structure” (108). Taken together, Loos’s titles and Blondes show a cross-genre relationship of exchange that brings modernist ideas about language into the vernacular culture that had been thought antipathetic to them. Like modernist writers such as Joyce and Stein, Loos changed reading practices, but she did so without resorting to strategies of unpleasure. Her narrative innovation in both film and literature pivots around the profusion, rather than the curtailment, of pleasure.

REVOLUTIONARY SIMPLETONS

Blondes appeared at the height of the modernist parsing of pleasure based on the exercise of cultural distinction. The novel—like all of Loos’s writing—draws much of its comedy from this discourse in which certain (feminine, bodily, visual, sensual, collective: “blonde”) pleasures are constructed as culturally corrosive and others (cerebral, individualized, written) are favored as edifying and worthwhile. Loos, for whom both modes are compelling, slyly demonstrates how acts of cultural classification (and their undoing) are themselves pleasurable.

Leavis’s Fiction and the Reading Public designates Blondes as representative of popular fiction published in 1925, asserting that the novel’s “slick technique is the product of centuries of journalistic experience and whose effect depends entirely on the existence of a set of stock responses provided by newspaper and film.” The correlation of Blondes and cinema, intended as a slight, is an acute observation. However, Leavis’s conception of mass culture—“crude and puerile,” “made up of phrases and clichés that imply fixed, or rather stereotyped, habits of thinking and feeling”—is willfully reductive: she could only wish that the attractions of mass culture were so nugatory. Leavis’s contrast between the pleasures of popular culture—bodily, auditory (music, voice), or visual (cinema)—and those of high culture—cerebral and textual (“the free play of ironical intelligence in Passage to India and To the Lighthouse”)—is the very paradigm around which Loos shapes Blondes.9 Leavis seems amazingly (conveniently?) unaware of the fact that Loos both indulges in and satirizes idioms of mass culture.

Like Leavis, Wyndham Lewis describes Loos’s language as distinctively colloquial and verbal (spoken and heard rather than written) in his surprising comparison of Loos and Gertrude Stein, in which he calls Blondes “the breathless babble of the wide-eyed child.”10 (In The Long Week End, Graves and Hodge also highlight the “artless pseudobaby language” of Blondes.11) Lewis joins Leavis in emphasizing Loos’s affiliation with cinema, dubbing her, together with Charlie Chaplin, “revolutionary simpletons.”12 Continuing this taxonomy of body and cinema versus mind and text, Cyril Connolly’s Enemies of Promise (1938) places Blondes in the category of “Vernacular,” as opposed to “Mandarin” literature (for example, Eliot’s Poems and Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway). Hemingway is “the outstanding writer of the new vernacular”; he writes in “a style in which the body talks rather than the mind, one admirable for rendering emotions; love, fear, joy of battle, despair, sexual appetite, but impoverished for intellectual purposes.”13

For all these critics, the distinctions between low and high, popular and elite, image and word, cinema and literature, are functions of the quality of pleasure produced. As we have seen, these polarized classifications of pleasure, in which cinema is inevitably the placeholder for cultural degeneration, are often so strict as to be farcical, and seem almost to beg to have their terms tousled. For Loos, such ideological inconsistency, whereby those who claim to be most invested in cultural distinction are receptive to the voluptuous allure of denigrated pleasures, is a springboard to satire. Loos cannily named Lorelei after a mythological Rhine Maiden, a Siren, that figure around whom Horkheimer and Adorno shape their Enlightenment dichotomies (modernism versus mass culture, mind versus body, bourgeois intellectual versus proletarian laborer, and “‘masculine’ rationalization” versus “‘feminine’ pleasure,” as Rita Felski puts it.14) Many intellectuals, lashed to the mast of cultural distinction, savored the giddy pleasures of Blondes. (It is a happy coincidence that, at least according to Heine, the Teutonic Lorelei was, like Loos’s siren, a blonde.)

In a context in which approved pleasures are deliberate, complex, and cerebral, Loos’s novel is strategically lightweight. When Lorelei is traveling through “the central of Europe” (B, 75), she goes to Vienna and sees the great doctor himself for psychoanalysis. “Dr. Froyd” marvels at the fact that Lorelei has no inhibitions and does not seem to dream at night. She explains, “I mean I use my brains so much in the day time that at night they do not seem to do anything else but rest.” She appears to have no capacity for psychological conflict, sublimation, interiority, self-consciousness, or depth: in short, none of the interests of literary modernism. Lorelei recalls that Freud “seemed very very intreeged at a girl who always seemed to do everything she wanted to do” (B, 90). Loos gives Lorelei virtually all of the characteristics of mass culture: female, seductive, ravenously materialistic, American, and cinematic.

Blondes looks quite different if, instead of reading it as symptomatic of the degraded idiom of journalism or cinema, we see it as based on historically specific cinematic effects. The novel is framed by Lorelei’s film career: when it opens, she has retired, and her triumphant return to the movies closes the book. In between, she flits among some of Hollywood’s major names, meeting “Mr. Chaplin once when we were both working on the same lot in Hollywood” and lunching with “Eddie Goldmark of the Goldmark Films,” who is based on the film mogul producer Samuel Goldwyn (B, 6, 16). More fundamentally, the language of the novel and its visual qualities are drawn from the distinctive voice Loos developed ten years earlier within silent film.

GOING TO THE MOVIES TO READ

The story of literary modernity includes mass-produced texts such as newspapers and magazines, billboards, and other forms of advertising that inspired, for example, the skywriting in Mrs. Dalloway and the skittering Hely’s sandwich-board men in Ulysses. However, the huge words that silent cinema routinely cast in front of audiences are rarely a part of this historical narrative. Titles were introduced into silent film as the functional heirs of the nickelodeon projectionist who read out information to the audience. In early Edison films, titles were explanatory devices that patched over gaps in the narrative; in the early 1910s, they started to include direct dialogue.15 For the most part, titles were perfunctory, establishing only basic narrative facts; most filmmakers and critics regarded them as a crude but necessary tool indicating the technological limitations of silent film. In his influential Photoplay: A Psychological Study (1916), Hugo Münsterberg opines that intertitles should be regarded as “extraneous to the original character of the photoplay”; they are “accessory, while the primary power must lie in the content of the pictures themselves.”16 Manuals for aspiring photoplay writers published in the 1910s insisted that “the use of a leader [title] is a frank confession that you are incapable of ‘putting over’ a point in the development of your plot solely by the action in the scenes—you must call in outside assistance, as it were.”17 (Elinor Glyn repeats the same point almost verbatim in The Elinor Glyn System of Writing: “If possible, make your plot clear without using any sub-titles; for the use of one is the frank confession that you are not able to bring out certain phases of your plot without resorting to the written word.”18) The vigorous discussion about titling in film magazines and newspapers in the 1910s and early 1920s, Laura Marcus observes, raised “fundamental questions about the nature of film language and, indeed, the extent to which cinematic images could be understood as elements of a language.” Captions and intertitles were an “intrusion of the literary into what should be an essentially pictorial realm.”19 They were not, in the early 1910s, considered an artistic form for individual authorship, only anonymous and banal placeholders. Loos changed this.

Loos’s debut in cinema was precocious and auspicious. D. W. Griffith bought one of her first scenarios, which became a 1912 one-reeler, The New York Hat, starring Mary Pickford and Lionel Barrymore. Her early scenarios were fairly conventional, but she was already experimenting with words not just as representations of ideas but also as objects with their own material status. Loos’s 1914 one-reeler The School of Acting features Professor Bunk’s drama school, in which thespians are taught to emote according to “large cards, about two feet square, [on which Bunk] has printed in big type the names of the different emotions; such as ‘Anger,’ ‘Jealousy,’ ‘Love,’ ‘Hope,’ etc.”20 Comedy ensues when actors are shown the cards in inappropriate circumstances and cannot help but act them out. The cards suggest titles, which cinema audiences read in tandem with the actors in the film, causing a metatextual collapse of viewer/actor and word/image. In “By Way of France,” a young Frenchwoman is kidnapped upon her arrival in New York; she manages to drop a note pleading “au secours! au secours!” but efforts to save her are thwarted because the man who finds the note cannot read French. Finally he locates a French dictionary and rescues her; they exchange a note: “Je t’aime” (AL Rediscovered, 28–29). Both films revolve around texts as concrete images—material combinations of letters—and the complications caused by faulty readings of words. The titles do not just elucidate the plot but are themselves the plot. Both films express anxiety about literacy and cinema audiences’ ability or willingness to extend their attention to reading.

In the mid 1910s, Loos’s future husband, John Emerson, pitched some of her screenplays to Griffith, who pointed out that they did not follow the usual protocol: “most of the laughs are in the dialogue which can’t be photographed,” he said, and “people don’t go to the movies to read.”21 Nevertheless, in 1916, Loos displayed her idiosyncratic style of titling in her first of many screenplays for Douglas Fairbanks, His Picture in the Papers. Loos led with a lengthy text: “Publicity at any price has become the predominant passion of the American people. May we beg leave to introduce you to a shining disciple of this modern art of ‘three-sheeting,’ Proteus Prindle, producer of Prindle’s 27 Vegetarian Varieties.” Parodying the Heinz Corporation with its “57 varieties” and the current fad for vegetarianism, Loos addresses her readers sarcastically (“a shining disciple of this modern art”) and peppers her sentences with alliteration, mixing precious locutions (“May we beg leave to introduce you”) with slang (“three-sheeting”). A saucy title announces a scene in which Pete Prindle, the carnivorous son of Proteus Prindle (and brother of “PEARL AND PANSY … KNOWN AS ‘28’ AND ‘29’”), kisses his girlfriend, who has previously received a “hygienic kiss” from a vegetarian: “Wherein it is shown that beefsteak produces a different style of love-making from prunes.” Late in the story, a title comments about Pete: “Ain’t he the REEL hero?” This punning voice establishes an autonomous level of commentary that self-consciously gestures at the film’s REEL medium and the title’s REAL textuality.

The film was considered a milestone in titling, and Loos received widespread attention in industry and general interest publications. Louella Parsons declared in the New York Telegraph that Loos had “revolutionized” titling.22 Fairbanks signed an exclusive contract with Loos in 1916 to write the titles for all his films. In an article for Everybody’s Magazine called “The Handwriting on the Screen,” Fairbanks told Karl Schmidt that “Time and again … I have sat through plays with Miss Loos and have heard the audience applaud her subtitles as heartily as the liveliest scenes.”23 Even an antititling critic such as Vachel Lindsay, who bemoaned that “‘Title writing’ remains a commercial necessity,” conceded that “in this field there is but one person who has won distinction—Anita Loos,” who was as “brainy” as anyone could be “and still remain in the department store film business.”24 Loos saw titling as a locus of linguistic creativity and authorial power in film. “Titling pictures had all the fascination of doing crossword puzzles but was a lot more fun,” she remarked (GI, 103), using a metaphor that is not far off from the serious whimsy of modernists such as Joyce. Loos’s titles, which film historian Kristin Thompson calls “the Loos-style title,” or the “‘literary’ inter-title,” instigated the recognizable shift to witty and prolix titles in some films of the late 1910s.25 Fundamentally changing the concept of cinematic pleasure as passive vision (“they need only sit and keep their eyes open,” Huxley writes in “Pleasures”), Loos’s titles presumed and even created an active audience to whom they offered a new kind of pleasure: literary visual pleasure. Loos did not just coax people to read; she taught them to view words as images. American Aristocracy (1916), another Fairbanks film, is an exemplary “Loosstyle” script. The opening title asks, “Has America an aristocracy? We say yes! And to prove it we take you to Newport-by-the-Sea, where we find some of our finest families whose patents of nobility are founded on such deeds of daring as the canning of soup, the floating of soap and the borating of talcum.”

Satirizing the insular Newport colony, where capitalism produces its own aristocracy (“patents of nobility”), the film’s titles include puns, euphemisms, mock Latin, and other fairly intricate jokes, along with written documents—letters, newspapers, ads—that were commonly used in films at the time. But while the interpolated documents are incorporated into the plot in the conventional way (that is, the audience reads them as the characters read them), the intertitles are often detached from the plot, either commenting upon it or embarking on an entirely new conversation. Thompson refers to this aspect of Loos’s titles as “double functioning,” in which “almost every expository title that begins a scene also makes a verbal joke of its own”—a style quickly taken up by other comic writers, including Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd.26

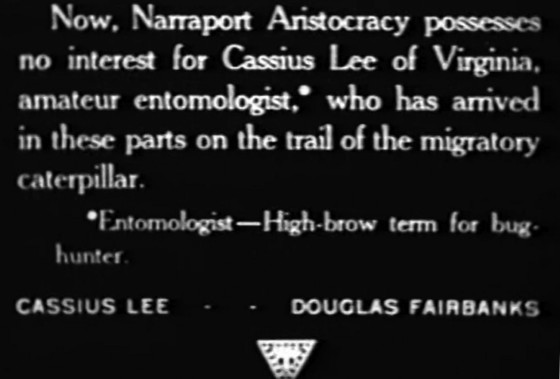

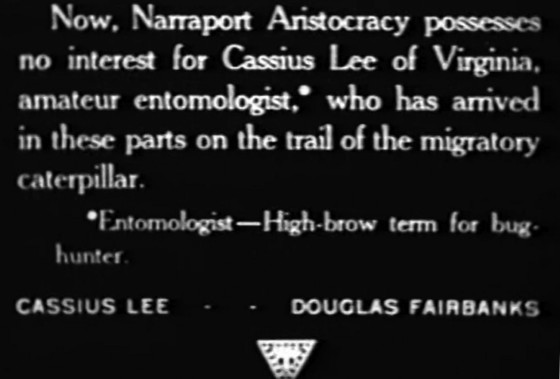

The hero of American Aristocracy, played by Fairbanks, is introduced by a title:

Now, Narraport Aristocracy possesses no interest for Cassius Lee of Virginia, amateur entomologist,* who has arrived in these parts on the trail of the migratory caterpillar.

*Entomologist—High-brow term for bug hunter

The footnote creates a level of diegesis two times removed from the cinematic plot (film diegesis: intertitle: footnote to intertitle). Moreover, the footnote splits the author’s voice between one that uses a “high-brow” term (and a pseudo-scholarly flourish like a footnote) and another that undermines this pretension. Loos never missed an opportunity to set high and low against each other.

American Aristocracy, Lloyd Ingraham, 1916.

In “The Handwriting on the Wall,” Loos told Everybody’s Magazine that her “most popular subtitle introduced the name of a new character. … The name was something like this: ‘Count Xxerkzsxxv.’ Then there was a note, ‘To those of you who read titles aloud, you can’t pronounce the Count’s name. You can only think it.’”27 The title, as described by Loos, establishes a direct relationship between the audience and the writer that entirely excludes the film. It insists that this jumble of letters cannot be treated as an oral artifact. Language here is neither visual nor audible, but rather located in an abstract realm of thought. Words don’t just represent ideas: they are ideas in themselves. The fact that Loos considered this title—explicitly allusive and self-reflexive—her “most popular” suggests how differently she imagined her audience from most critics of the time. Loos’s cinema offered the pleasures of interpretation and irony—those “mandarin,” “subtle,” and “intelligent” pleasures that Leavis, Connolly, Huxley, and others claimed were the purview of serious literature. Loos invited audiences to enjoy the collision of different levels of cultural pleasure.

This was an exceptional historical moment when film could be exploited for literary purposes, and Loos did just that, by flouting current theories that film should strive to be a purely visual form and the idea of cinema as a seamless illusion with invisible techniques. Ignoring the injunction of critics such as the New York Dramatic Mirror’s Frank Woods that, “the spectators are not part of the picture, nor is there supposed to be a camera there making a moving photograph of the scene,”28 Loos’s titles directly addressed the spectator, the cinematic equivalent of breaking the fourth wall. Against the idea of film functioning like hieroglyphics (promulgated by Vachel Lindsay) or as a universal language healing the linguistic fragmentation of the Tower of Babel (associated with Griffith),29 Loos crafted a highly idiomatic cinema that cultivated tension, rather than harmony, between text and image. In her cinema writing and subsequently in Blondes, she employs a number of techniques to promote this pleasurable conflict between word and image: visual and graphic subordination (subtitles, captions, footnotes), punning, homophones, phonetic spelling, a split voice, and a kind of artistic synesthesia (asking audiences to read images and see words).

Loos’s 1919 short story “The Moving Pictures of Blinkville” dramatizes the process by which the pleasures of the text compete with the pleasures of the image. A trickster pretends to be a filmmaker. After the town’s denizens pose for his camera, he takes an old parade film and transforms it “by long and labored work at scratching and clouding the film,” like a form of writing. The resulting movie “projected on the curtain was not a picture—it was a series of blurs and blotches, with here and there a human form indicated amid the surging storm of scratches.”30 He shows it to great acclaim as “Scenes of Blinkville.” The word, which is supposed to be subordinate to the visual spectacle, is rendered concrete and assumes a starring role. Audiences, without realizing it, are induced to “read” a film. Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Our Own Movie Queen” (1925) demonstrates the effects of this new style of intertitling. When a small-town girl is all but cut out of a film in which she thinks she is going to be the lead, she and her boyfriend exact revenge by inserting new images and intertitles (set off from the regular text in the story to simulate the shape of the screen) to make her the star.31 Thanks to Loos, titles had their own kind of textual autonomy.

At no other time in cinema history did the word exert so much power. Loos continued to capitalize on the battle between the image and the word and the related disputes about hierarchies of cultural pleasure in Blondes. One film project was unexpectedly influential for Loos and for Blondes: Intolerance.

“A BATHTUB FULL OF DIAMONDS”: INTOLERANCE

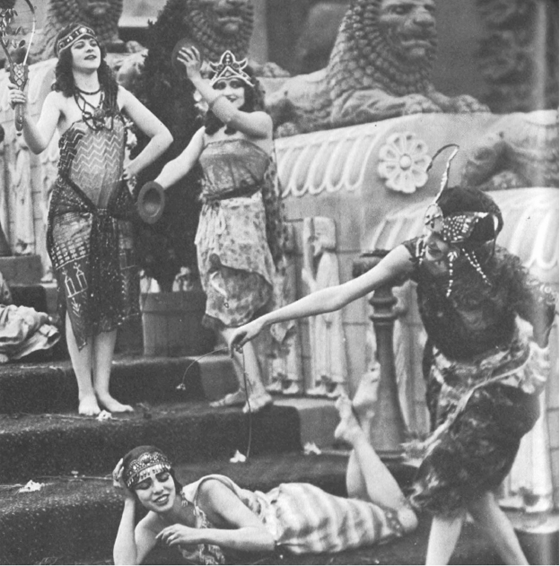

While Fairbanks’s films represent classic Hollywood cinema, Griffith was a figure caught between convention and innovation, pulling back toward the theater and forward toward cinema’s future with innovative techniques that inspired experimental filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein and have led more recent critics to view Griffith as an early modernist.32 Loos was invited to collaborate with Griffith and Frank Woods on the titles of Intolerance (1916). The film, approximately three hours long, presents a sweeping metanarrative, the “history of how hatred and intolerance, through all the ages, have battled against love and charity.” Intolerance has a fuguelike structure that uses parallel montage to intercut among four narratives set in different eras (Babylonian, biblical, seventeenth-century France, and modern day). Each narrative features characters (many of whom are given generic titles such as “The Dear One,” “The Boy,” and “The Friendless One”) who act out analogous scenarios of oppression or “intolerance.” In the Babylonian narrative, one priest violently represses a more hedonistic sect; in the biblical narrative, Jesus is martyred; in the French narrative, Huguenots are slaughtered on St. Bartholomew’s Day; and in the modern-day story, a workers’ strike is violently suppressed and a selfrighteous group of female reformers destroy a family.33

Loos claims that she was “the first viewer ever to see Intolerance [in the editing room]. I must be honest and say I thought D. W. had lost his mind. … In that era of the simple, straightforward technique for telling picture plots, Griffith had crashed slam-bang into a method for which neither I nor, as was subsequently proved, his audiences had been prepared” (GI, 102). The dominant models of spectatorship—intoxication or passive escape—fail to account for Intolerance, which requires its audiences to synthesize four widely disparate historical narratives and to relate allegorical images (the Book of Intolerance, the woman—Lillian Gish—rocking the cradle) to the stories around them. Intolerance calls upon its audience to construct its meaning, but it gives assistance through didactic titles, beginning with a sequence that addresses the viewer and explains how to watch the film—“you will find our play turning from one of the four stories to another, as the common theme unfolds in each”—and marking many of the bridges between the film’s different time frames. The titles are remarkably variable in style and tone, reflecting, no doubt, the three different authors who worked on them. Many titles are bombastic and heavy-handed (for example, “My Lord, like white pearls I shall keep my tears in an ark of silver for your return. I bite my thumb! I strike my girdle! If you return not, I go to the death halls of Allat”).

In most cases, we can only speculate which writer was responsible for which title, but the stylistic differences are suggestive. Loos was clear about her role. In her memoir, she recalls, “D. W. bade me put in titles even when unnecessary and add laughs wherever I found an opening. I found several” (GI, 103). Interspersed among the instructive and weighty inscriptions are lighter and more ironic captions that seem more reflective of the “Loos style.” For example, in the scene in which The Dear One, who has jealously watched a woman’s undulating walk draw men’s attention on the street and decides to imitate it by tying her skirt into a hobble, a title dryly comments, “The new walk seems to bring results,” as men flock to her ridiculous gait. In the marriage market in Babylon, when no one bids on the feisty Mountain Girl, she shouts at them, “You lice! You rats! You refuse me? There is no gentler dove in all Babylon than I.”

Some titles are more subtle, as when the repressive High Priest of Bel-Marduk is threatened by the rival cult of Ishtar. The title remarks, “He angrily resolves to reestablish his own god—incidentally himself.” The final modifier sarcastically comments from outside the action in a distinctly contemporary idiom. The tone does not match the image, and the title elicits a snicker whereas the image is aiming for sober drama. Later in the film, in the modern narrative, when The Boy is framed and put in jail, the title remarks, “Stolen goods, planted on the Boy, and his bad reputation, intolerate him away for a term.” The verb form “intolerate” can be read as a teasing poke at Griffith’s tendentious insistence upon the word and the concept of intolerance, which often seems like an elaborate defense against criticism of his race politics in Birth of a Nation.

Griffith shared with Loos an interest in making films more porous to high culture, as reflected by his use of Whitman and other literary and artistic intertexts. However, while Griffith used this material in a fairly traditional style, as epigraph or thematic support, Loos’s literary intertexts are usually cheeky. The one title for which Loos routinely claimed credit—the most controversial title in Intolerance—is such a text. She recalls, “At one point I paraphrased Voltaire in a manner which particularly pleased D. W.: ‘When women cease to attract men, they often turn to reform as second choice’” (GI, 103). It may seem odd that Loos would claim authorship of a quotation that is arguably misogynist, but she never hesitated to distance herself from feminism. Loos’s idea of female empowerment is more Sex and the Single Girl than suffragette, and she was always at pains to emphasize her girlishness and insignificance even as she, like her titles, stole the spotlight. (Writing about how Blondes had been inspired by Mencken’s barbs aimed at his fellow Americans, she remarks, “My book was certainly an offshoot of Mencken’s point of view, just as a gadget can be produced by the important theory of a scientist” [GI, 217]). Loos flaunted superficial signifiers of cultural capital in her intertitles, not so much to make films “smarter” but to disrupt the expected relationship between the image and the word, vacuous mass culture and clever high culture. The epic complexity of Intolerance—its heterogeneity, didacticism and suggestion, melodrama and innovation—challenged Loos to produce a subtle, insinuating voice for a film that defied current cinematic conventions and concepts of cinematic pleasure.

Vachel Lindsay writes, “Anita Loos once said to me that Intolerance was ‘a bathtub full of diamonds’. … It was a humorous way of proclaiming that there were enough suggestions in Intolerance, to producers of imagination, to last the motion picture world for fifty years.”34 This is certainly the case, but here Loos speaks, significantly, in the idiom of Lorelei: “kissing your hand may make you feel very very good but a diamond and safire bracelet lasts forever” (B, 55). Loos explicitly connects Intolerance to the world of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by giving Lorelei a cameo in the film. “I was doing quite well in the cinema when Mr. Eisman made me give it all up,” Lorelei remarks at the beginning of Blondes (B, 6). Her “last cinema,” was Intolerance, in which she played “one of the girls that fainted at the battle when all of the gentlemen fell off the tower” (B, 8). The battle in question is the fall of Babylon, which indicates Lorelei’s definition of “gentlemen.” Lorelei’s appearance in the film is preposterous but also has a particular logic to it.35

As Miriam Hansen notices, one of Intolerance’s dominant themes is the “fate—and fatal power—of unmarried female characters throughout the ages” and how their environment thwarts or supports them; Michael Rogin adds that many of the narrative threads in the film promote female sexuality and public pleasure.36 The Babylonian narrative in which Lorelei acts features open eroticism, feasting, and elaborate dance sequences (according to accounts from the set of Intolerance, some of the extras hired to appear seminude in the scenes were, as Lorelei would say, “not nice”37). Griffith’s film is sympathetic to women of pleasure who are the victims of intolerance: the temple prostitutes/“Virgins” in Mesopotamia, Mary Magdalen, and the women who are herded out of the bordello under the gleeful eyes of the modern-day reformists (the subjects of Loos’s “female reformers” title). Both Griffith and Loos were fascinated by hypocritical reformers. Henry Spoffard, who becomes Lorelei’s husband, is a wealthy cinema “senshur” who likes to assemble the “riskay” scenes he has excised into a sort of reformist stag film that he watches recreationally with other men (B, 102). At one point in Blondes, Spoffard tells Lorelei that she “seemed to remind him quite a lot of a girl who got quite a write-up in the bible who was called Magdellen. So then he said that he used to be a member of the choir himself, so who was he to cast the first rock at a girl like I” (B, 93).

Loos leads her reader to infer a somewhat seamy quid pro quo underpinning the economics of Lorelei’s glamorous life, but critics are divided about exactly what goes on. Barbara Everett describes Lorelei as “a cherubic-faced nail-hard amateur whore” (254); Regina Barecca remarks that Lorelei and Dorothy are “closer to con artists than to whores … far from professional courtesans” (xvii); Katharina von Ankum states that Lorelei “preserves her virginity” until she marries Spoffard.38 All these readings are technically plausible. “Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure” is as euphemistically apt a subtitle for Blondes as “The Illuminating Diary of a Professional Lady,” which Loos, always taking advantage of structural subordination, subtitled her novel. What is certain is that Lorelei, like the profession to which she gravitates, the cinema, is in the business of selling pleasure. Loos went on to exploit Intolerance’s linguistic subtleties and thematics of pleasure in Blondes, where she plays Griffith’s vast historical epic as local comedy.

Intolerance, D. W. Griffith, 1916.

GENTLEMEN PREFER TYPISTS

According to Lorelei, she has “been” three careers. Back when she was still going by her given name, Mabel Minnow, her father sent her to “the business colledge” in Little Rock, but after just a week, a lawyer named Mr. Jennings hired her to be his new stenographer. She reports that she “stayed in his office about a year”—doing exactly what, she does not say (B, 24). Lorelei’s first job links her to one of modernity’s favorite female icons, the secretary or typewriter girl,39 who embodies the paradoxes of female pleasure and technologies of writing in ways that anticipate the cinema spectatrix and the cinema writer. On the one hand, the stenographer/typist/secretary earns money and works in the public sphere. On the other hand, hers is a labor of automatism, Marx’s “dead labor,” regurgitating the words of others. She is connected to writing, but only in the passive sense of recording or transposing someone else’s (usually her male boss’s) thoughts. Her job is copying, transposing, correcting errors, and rendering her work transparent; she has no distinctive authorial signature. She bears a remarkable resemblance to the cinema titler before Loos transformed that role.

The typist’s primary identity is as a worker, but there is, as Christopher Keep notes, an “excessive, almost obsessional fascination … with the assumed promiscuity of the female typist.”40 As Lawrence Rainey remarks, “The typist, after all, is repetition personified,” but she is also imagined as “represen[ting] the promise of modern freedom: an allegedly new, autonomous subject whose appetites for pleasure and sensuous fulfillment were legitimated by modernity itself.”41 But the nature of the typist’s pleasures tends to be imagined as analogous to her production of language: anonymous, automatic (like Eliot’s robotic typist in The Waste Land, for whom sex is anhedonic). Loos wrote several screenplays exploring the misreadings accruing around this amanuensis of alienated words. Erik von Stroheim’s The Social Secretary (1916) follows a stenographer who loses several jobs because she is harassed by her male employers, including a boss at the office of the New York Purity League who looks at “riskay” pictures—a forerunner of Henry Spoffard. Virtuous Vamp (1919) also features a talented stenographer who is fired because she distracts the men around her from their work. In Red-Headed Woman, Jean Harlow plays the stenographer as a “sex pirate.”42 By giving Lorelei a brief past as a stenographer, Loos invokes all the narrative clichés associating debased writing and pleasure that surround this handmaiden of modern literature. Even more significantly, it is through this so-called career that Lorelei is “discovered.”

Lorelei’s stenography stint comes to an end when she catches Mr. Jennings with “a girl there who really was famous all over Little Rock for not being nice” (B, 24–25). Lorelei recalls that when she “found out that girls like that paid calls on Mr. Jennings I had quite a bad case of histerics and my mind was really a blank and when I came out of it, it seems that I had a revolver in my hand and it seems that the revolver had shot Mr Jennings” (B, 25). Lorelei’s revolver is part Hedda Gabler, part Mae West, but it is recast as an instrument that conveniently—like the typewriter—erases her agency. During her murder trial, Mabel Minnow seduces the jury with her damsel-in-distress routine and is acquitted. The judge, who appreciates her act, bestows upon her a ticket to Hollywood and the stage name Lorelei Lee. “I mean it was when Mr. Jennings became shot,” she remarks, “that I got the idea to go into the cinema” (B, 25). Never has the passive tense been deployed so tactically.

In making stenography the gateway to stardom, Loos cannily invokes the popular discourse of the 1920s that associates the typewriter girl with cinema.43 As Kracauer remarks, “Sensational film hits and life usually correspond to each other because the Little Miss Typists model themselves after the examples they see on the screen.”44 Iris Barry argues that one of cinema’s key consumers is “The typist in search of a thrill.”45 The typist career and the spectatrix pastime seem to support each other; as Freidrich A. Kittler puts it, “at night [women] are at the movies and during the day they sit at their typewriters.”46

The typewriter and the cinema are connected materially (both are American, individuality-flattening technologies that traffic in copies) as well as imaginatively. Both are understood as feminized and offering paradoxical pleasures. Early film critics describe cinemagoing as an experience of fantasy and escape, but they also imagine cinematic pleasure as banal and standardized. (“That which determines the rhythm of production on a conveyer belt is the basis of the rhythm of reception in the film,” Walter Benjamin remarks in “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire.”47) Even Barry, one of early cinema’s greatest advocates, describes “The second-hand experience derived from the pictures, the imitation excitement,” as “almost as standardized as a church service or a daily newspaper.” She laments, “I wish that the public could, in the midst of its pleasures, see how blatantly it is being spoon-fed, and ask for slightly better dreams.”48 This is modernism’s familiar double bind: it must account for the fact that mass culture is enormously compelling but also a kind of false consciousness.

Loos turns to the typewriter girl to constellate—and also recast—the connection among mechanized writing, debased pleasure, and cinema writing. Lorelei, we can safely assume, is not much of a typist: she writes her diary in longhand, and not very well at that. And Lorelei is not a spectatrix but a would-be actress. The cinema turns out to be the closest thing to a true profession for her. In making cinema a place of production rather than consumption, Loos alters the standard trope of passive celluloid just as her trademark cinematic style diverges from the paradigm of hypnotic spectatorship. The titler herself is historically positioned like the typist, alienated from her labor; Loos alters that by reinventing the form.

Loos fashioned not just Lorelei but also herself through the typist–cinema correlation. In her memoir A Girl Like I, a phrase taken from Lorelei (Loos often slips into such Loreleisms, in her essays as well), Loos chose to reproduce a Ralph Barton sketch of herself, a wellknown cinema writer, as a cutely infantile typewriter girl. Antonia Lant suggests that the proliferation of publicity shots of female cinema writers at their typewriters in the 1920s was a way of solving the “awkwardness in efforts to signify women’s acts of film writing, given the cultural desire to make her an object of visual study.”49 Loos uses the standard shot to render writing visual in a much more complicated way, adding a caption to the image in which she adopts the voice of Lorelei: “The only thing wrong with this picture is that an authoress like I never learned how to type” (GI, unnumbered insert between 150 and 151). Like her cinema titles, this text that is supposed to be subordinate to and explain the image instead upstages it. Ostensibly revealing Loos’s shortcomings, it in fact makes her superior to the typist. The sentence reflects the anxiety that cinema titling is regarded like typewriting: debased, anonymous and subordinate, an inartistic stream of banal formulas rather than the individualized, scripted work of a legitimate writer.

On the same page of A Girl Like I, below Barton’s drawing, is a photograph of Loos sitting at a desk with a pen in her hand, a seemingly straightforward portrait of the artist at work. Yet Loos adds this caption: “My sole preparation for a career was to buy a fountain pen and a large yellow pad: no dictionary or grammar required. Some day I’ll give a course on how to succeed in literature without any learning.” This idea of producing literature without learning is as ironic the usage of the words “education” and “literary” in Blondes. While Lorelei inflates these words and her own “literary” labor, Loos deflates them and the self-important disingenuousness with which they are deployed by the many would-be seducers who “educate” Lorelei through showing her art and bestowing upon her highbrow books. Loos implicates the typist and the caption writer (analogous to the subtitler as a producer of text linked to an image) to position herself between low and high cultural pursuits.

Ralph Barton cartoon of Anita Loos Courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

In her film writing, Loos routinely disrupts visual pleasure and puts in its place the pleasure of the text. In Blondes she follows the same principles, but because of her medium, the effect is slightly different. Her cinematic language creates literary visual enjoyment and her novelistic language creates visual literary pleasure. Lorelei, acting as authoress in Blondes, writes in language that induces the reader to see words as images.

“TRANSPARENT NEGLIGAYS AND ORNAMENTAL BATH TUBS”

Blondes is a visual novel in several senses. Most obviously, it is illustrated by Ralph Barton, who was under contract with Harper’s Bazar: A Repository of Fashion, Pleasure and Instruction (it became Harper’s Bazaar in 1929), where Blondes first appeared in serialized form. Loos was not responsible for the images, but they are routinely included in editions of the novel, so they have become part of its textual apparatus. As it happens, they reflect Loos’s preoccupation with technologies of writing. The first illustration shows Lorelei at her desk with a pen, writing in her diary: exactly the same pose as Loos’s publicity photo. The humorous caption Loos appended to her own portrait is perfectly appropriate for this occasion: Lorelei has “succeeded in literature without any learning.” Barton’s second illustration shows Lorelei on a couch with a stack of books scattered around her, looking perplexed. When a “literary” admirer (a novelist) gives Lorelei “a whole complete set of books for my birthday by a gentleman called Mr. Conrad” in an effort to “educate” her, she asks her maid to read and summarize them; she comes to the conclusion that “They all seem to be about ocean travel” (B, 8). Lorelei is only marginally literate, but her mistakes have the effect of calling attention to the concrete qualities of her writing.

Lorelei’s voice is reminiscent of other unreliable or idiosyncratic narrators—John Dowell, Nick Carraway, Molly Bloom—and Loos adds a linguistic layer of textual play through Lorelei’s misspellings and malapropisms. Even as Loos constantly signals toward the textual production of Blondes through these mistakes, critics such as Leavis, Lewis, and Connolly take her narrator literally (“But writing is different because you do not have to learn or practice”) and understand her voice as purely physical—oral, idiomatic, and “artless pseudo-baby language.” They focus on the verbal qualities of Lorelei’s narrative and perceive it as “uncrafted” bodily speech rather than scripted language. Lorelei’s phonetic spelling and punctuation errors, along with Loos’s innuendos, euphemisms, and double entendres, do lend themselves to this reading—for example, Lorelei’s explanation that “of course when a gentleman is interested in educating a girl, he likes to stay and talk about the topics of the day until quite late,” or Dorothy’s suspicions about a girl in Paris who claims to be eighteen: “how could a girl get such dirty knees in only 18 years?” (B, 4, 66). However, most of the humor of Blondes depends upon visual wordplay.

Lorelei’s trip to Europe affords Loos an opportunity to make multilingual puns (for example, Lorelei’s adventure with the French con artists “Louie and Robber,” and her visit to “Fountainblo” and “Momart” [B, 63]). Lorelei remarks that “French is really very easy, for instance the French use the word ‘sheik’ for everything, while we only seem to use it for gentlemen when they seem to resemble Rudolf Valentino” (B, 69). Loos frequently crafts homophone puns such as “Sheik”/“chic” or “Hofbraü”/“half brow” (B, 86), which, although based on words sounding alike, have to be seen to be perceived (like the “real”/“reel” pun in His Picture in the Papers). As with the cinema title about the unpronounceable Count Xxerkzsxxv—which looks like a vengeful secretary has pounded on random typewriter keys—Loos’s language in Blondes highlights the details of its construction.

Faulkner’s 1925 letter to Loos illustrates the many levels of voice and awareness in Blondes:

Please accept my envious congratulations on Dorothy—the way you did her through the intelligence of that elegant moron of a cornflower. Only you have played a rotten trick on your admiring public. How many of them, do you think, will ever know that Dorothy really has something … My God, it’s charming … most of them will be completely unmoved—even your rather clumsy gags won’t get them—and the others will only find it slight and humorous. The Andersons [Sherwood and Elizabeth] even mentioned Ring Lardner in talking to me about it. But perhaps that was what you were after, and you have builded better than you knew. … 50

It is no wonder that Faulkner prefers Dorothy, Lorelei’s brunette sidekick, who is the voice of overt irony, modernism’s signature rhetoric, in Blondes. Faulkner divides the readers of Loos’s novel into those aligned with Lorelei (the “admiring public”) and those aligned with Dorothy (educated readers). Faulkner is not so sure where Loos herself falls. Mentioning Lardner, the acknowledged master of modern American vernacular, Faulkner then revokes the compliment by suggesting that the effect was not deliberate, but also jokes back at Loos by imitating Lorelei: “you have builded better than you knew.” Faulkner assumes two separate and hierarchical audiences who experience two different reading effects (irony versus mere humor), two different levels of comprehension, and hence two different kinds of pleasure. He does not acknowledge the ways Lorelei (who is hardly “elegant”), as scripted by Loos, is an only half-proficient writer but a master of strategy. Lorelei’s voice is, in fact, more complex than Dorothy’s sophisticated but straightforward irony. Her grasp of language is comical, but she is nevertheless skilled in dissimulation. She is a surreptitious editor of her own diary, expurgating all evidence that would contradict her carefully constructed image of herself and successfully manipulating everyone around her. Lorelei is not as dumb as she seems or as smart as she thinks she is. Making her a barely literate writer has the effect of estranging the reader from language. Loos makes sure we do not mistake these strategies for modernism—Lorelei is quick to dispatch the Conrad novels to her maid—but rather sustains the juxtaposition of mass and high culture.

At least Molly Bloom reads her own novels, even if they are “smutty.” But while Molly’s undulating run-on sentences are most intelligible when read aloud, Lorelei’s language, if read verbally (the way Leavis, Connolly, and Lewis seem to have approached it) would produce only a few laughs at the “rather clumsy gags” (e.g., “A girl like I”; “champagne always makes me feel philosophical”). If we are fooled into thinking that we are hearing Lorelei’s voice rather than seeing her script (transcribed by an unknown typist into the book before us), we are failing to see what is in front of us on the page. There is almost no descriptive imagery in Blondes, which is odd, given the “lookist” visual economy that rules the novel. Instead, Loos directs the reader to look at the words on the page, much in the same way that she scolds the cinema viewer who tries to pronounce ‘Count Xxerkzsxxv.’ One has to read and analyze the words on the page to see Loos’s more intricate jokes. Blondes follows the principles of her cinema writing and asks its audience to view language materially, as visual images.

One reader who paid close attention to the words on the page, despite his declining vision, was James Joyce. In the same 1926 letter in which Joyce tells Harriet Shaw Weaver that he has read Blondes, he describes his “Work In Progress,” which he put aside to read the novel. The next week (November 15), in a letter signed “Jeems Joker,” he sends Weaver the opening paragraph of Finnegans Wake.51 It is not hard to imagine why Blondes would have appealed to Joyce. Lorelei’s voice resonates with those of Joyce’s own Sirens (who appear, like Dorothy and Lorelei, “bronze by gold”), his Nausicaa, and his Penelope. In Joyce’s own exploration of a contemporary, uneducated woman’s voice in the final chapter of Ulysses, he merely jettisons punctuation, while Loos toys with all levels of language except syntax. Lorelei’s mangling of several languages—French and German as well as “the english landguage” (B, 88)—corresponds to the riot of languages in Finnegans Wake. Lorelei’s felicitous phrases (e.g., her “Eyefull Tower”) may have stayed with Joyce (“a waalworth of a skyerscape of most eyful hoyth entowerly.”)52 More than specific puns, however, it is Loos’s comic choreography of concretized language that seems relevant for Joyce. As Beckett remarked of Finnegans Wake, “Here form is content, content is form. You complain that this stuff is not written in English. It is not written at all. It is not to be read—or rather it is not only to be read. It is to be looked at and listened to. His writing is not about something; it is that something itself.”53 We are familiar with this argument made about modernist art, but not about vernacular culture.

Loos was keenly aware of modernist and avant-garde writing and art, joking about the contrivances of cubism and the daffyness of Dada.54 She visited Stein at the rue de Fleurus, but claimed to be less interested in her writing—which she described through Sherwood Anderson’s summary: “one should look on it as one looks at the palette of a painter, appreciate the words merely as words, and pay no attention to the context in which she placed them”—than she was in finding Stein, among Hemingway and Fitzgerald, “the most manly of the lot” (GI, 228). Loos routinely calls attention to the surface of words, like Stein’s word portraits, or Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1912), in which newsprint letters “JOU” are incorporated into the image as literary artifact and also as a pun. What is remarkable about Loos is that she deploys the “mandarin” mode of heightened textuality as the guiding principle of vernacular forms of culture without being gnomic, obscure, or inaccessible. For her, there was no inherent contradiction between these ostensibly different orders of pleasure, only systems of cultural classification—including elitism masquerading as “education”—that made this seem so.

When Lewis compared Loos to Stein, he argued that the former “intended to reassure the reader of the mass-democracy that all is well, and that the writer is one of the crowd … not a detested ‘highbrow.’”55 But Loos had a much wider audience in mind, and she aims to disarm rather than reassure, always sustaining the tension of cultural hierarchy as she views distinction from the middle of the great divide. Lorelei eagerly asserts the ways she is “literary”; simultaneously, Loos targets the self-styled “intelectuals” (modeled on Mencken) who fall for Lorelei but attempt to maintain their vaunted values of distinction. At the end of the novel, Lorelei convinces Spoffard to become a producer of titillating “pure films” (B, 120); their first production, “a great historical subject which is founded on the sex life of Dolly Madison,” stars Lorelei (B, 114). Simultaneously, she collaborates on scripts with her man on the side, Mr. Montrose, a frustrated screenwriter who “had quite a hard time getting along in the motion picture profession, because all of his senarios are all over their head. Because when Mr. Montrose writes about sex, it is full of sychology, when everybody else writes about it, it is full of nothing but transparent negligays and ornamental bath tubs” (B, 115). Loos’s work found a wide audience precisely because it allowed viewers and readers the pleasure of participating in cultural distinction and its undoing: a testimony to general audiences’ capacity to embrace the wit of linguistic play, and to “highbrow” audiences’ susceptibility to the pleasures of “transparent negligays and ornamental bath tubs.” Loos’s success suggests that she produced her ideal audience: a consumer who could read images and see words.

Other popular writers and artists began to reflect modernism back to itself. Several of Loos’s female contemporaries—including Mae West, Dorothy Parker, and Gypsy Rose Lee—similarly manipulated modernist sensibilities and stereotypical, conventional pleasures to forge new kinds of vernacular culture. Gypsy, for example, was dubbed the “Striptease Intellectual” for her idiosyncratic burlesque act in the late 1920s and 1930s, in which she delivered a sly lecture on art, literature, or classical music, or deconstructed the practice of striptease itself, with lines quoted from the likes of Algonquin Round Table wit Dwight Fiske, all while peeling off her clothes. Like Loos, Gypsy poked fun at the pretentions of pedagogy that sought to shore up the great divide. Gypsy also wrote pulp noir fiction, including the detective novel The G-String Murders (1941), plays, occasional essays for The New Yorker, and a sparkling memoir. Loos wrote about Gypsy in a section of A Cast of Thousands called “Women to Remember”: “Gypsy Rose Lee and I had some curious traits in common. … In early youth we had each appeared in rather basic vaudeville skits, during which period we whiled away some of our childhood hours reading The Critique of Pure Reason by Immanuel Kant. Why? Possibily [sic] as a counter-irritant to the gag lines we were forced to learn” (184). Gypsy and Loos both cultivated a distinctive voice (one wised-up, one dumbed-down) within their respective genres, using humor and cultural name-dropping to assert female pleasure. Throughout her career, Gypsy, like Loos, teasingly unsettled ideas about class, gender, and the perceived divide between high and low culture.56

The sound film put an end to the linguistic play of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Hawks’s 1953 film drastically revises the plot of the novel (Lorelei and Dorothy, now showgirls, sail to Europe for Lorelei’s wedding to Gus Esmond, and all but a few minutes of the film are set on the ship) and, most crucially, jettisons Loos’s first-person narration. What we gain in iconic sex appeal, we lose in textual complexity. Significantly, Dorothy’s jokes—broad irony—translated well to the sound film, while Lorelei’s did not. The only witticisms retained in Hawks’s film are obvious grammatical mistakes and malapropisms—for example, the phrase “A girl like I,” and Lorelei asking for directions to “Europe, France.” The pleasure of the text has dissipated. The disappearance of the text in cinema was strikingly marked within the film industry by the first Academy Awards in 1929, which gave the first and only Best Title Writing award to Joseph Farnham. (Gerald C. Duffy was posthumously nominated for his work on The Private Life of Helen of Troy, a film that sounds like a Spoffard production, or one of Huxley’s feelies.) The same year, a special award was given to Warner Brothers for The Jazz Singer, signaling what was to come. Ironically, some viewers, such as Q. D. Leavis, complained that the sound cinema further distanced people from the written word: “the ‘talkie’ … does not even offer captions.”57

Although Loos’s literary-visual voice disappeared from most film, her playful approach to cultural signification would become the stock in trade of the next generation. For writers such as William Burroughs, Jeanette Winterson, Kathy Acker, and Thomas Pynchon and artists such as Jeff Koons, Andy Warhol, and Cindy Sherman (whose respective images of Marilyn Monroe signal the paradoxical emptiness and thrill of replication58), consciousness about the divisions that marked modernism became sources of humor, critique, or self-reflection. The giddy juxtapositions of the sort that Loos performed exist in postmodernism in tandem with the lingering critique of pleasure.