“Pleasure is not always fun. …”

In Jean Rhys’s 1939 novel Good Morning, Midnight, the protagonist, who calls herself Sasha, is picked up by a male stranger on the Boulevard Arago during an evening walk. They go to a café and drink Pernod: one, two. … “I feel like a goddess,” she thinks. “I want more of this feeling—fire and wings.” The man puts his hand on her knee and invites her back to his flat. Sasha doesn’t particularly like him, but she remarks, “Well, why not?” When they walk out onto the street, she stumbles. “What’s the matter?” he asks. “Have you been dancing too much? … All you young women … dance too much. Mad for pleasure, all the young people. … Ah, what will happen to this after-war generation? I ask myself. What will happen? Mad for pleasure.”2

This is a comically flawed conclusion, as the man mistakes Sasha for a good-time girl, a shingled flapper out for thrills. Although Sasha is, in fact, eager to get drunk, she is poor, alone, and depressed, a broken marriage and a child’s death in her past. She sleeps most of the time and contemplates chloroforming herself, were it not for the fact that her hotel board has been paid for the month. She lurches in the street not because she is giddy from dancing, but because she is hungry and drinks on an empty stomach. Sasha goes along with the stranger even though she describes the encounter as “unhoped-for” and “quite unwanted” (397). In the novel’s final act, when she leaves her hotel-room door propped open to invite a menacing neighbor into her bed, her pleasure is dubious by any conventional definition.

Rhys’s transnational flâneuse would seem to epitomize modern feminine cosmopolitanism, as a creature who orbits contemporary amusements (clubs and restaurants, the cinema, popular music, cocktails, and freely chosen sexual companionship), yet she is plagued by anxiety and alienation. Sasha’s decisions are not calculated to produce what most would recognize as bliss or joy. Rhys’s narrative enacts Sasha’s erratic psychology through its fragmented form, shifting abruptly from one time frame and one scene to another, and dispensing with causality. Communication is cryptic; people are ciphers. On a local level, some individual scenes are poetic, playful, or witty, but the overall impression is one of disorientation and dislocation. Like Sasha, Rhys’s reader lurches from one episode to the next, a succession of flights and drops, delight and mostly dysphoria.

Sasha’s companion’s conception of “this after-war generation” as “mad for pleasure” echoes stereotypes of the interwar period: Daisy Buchanan jazz babies drinking cocktails and dancing in sleek art deco dresses, swooning in the cinema or listening to the latest thing on the gramophone. Rhys subsumes these experiences into the landscape of malaise and depression through which her protagonist drifts. In other modernist texts from the period—an era preoccupied by the miseries of the past war and the impending rise of fascism as well as the exhilaration and anxiety of shifting gender roles and new sensory cultures—embodied, direct, and easy pleasures have a dark side. Figured as a siren call, alluring and dangerous, they are both a compulsion and a disorder of the age. What would usually register as pleasure often becomes empty, dangerous, or even anhedonic. “Well now that’s done: and I’m glad it’s over,” T. S. Eliot’s typist in The Waste Land remarks, following a mechanical lovemaking session.3 As with Rhys’s novel, the form of Eliot’s poem echoes its representations of compromised pleasure, confronting its reader with language that is as demanding as it is captivating. Between the disjointed imagery, the foreign languages, and recondite, dense allusions, by the time the (at least first-time) reader reaches the poem’s final “Shantih shantih shantih” (69), she may breathe a sigh of relief too: “Well now that’s done.”

Many other modern and most high modernist texts complicate or defy classical conceptions of literature as an experience of pleasure (Aristotle4) or delight (Horace5) that continue into contemporary criticism. Posing the query, “What do stories do?” Jonathan Culler specifies that “First, they give pleasure.” Harold Bloom, who bemoans that “reading is scarcely taught as a pleasure, in any of the deeper senses of the aesthetics of pleasure,” proposes that literature’s purpose is rehabilitative and redemptive: it is “healing” and “alleviates loneliness.”6 To the contrary, modernists offer a challenging and even hostile reading experience that calls into question the most axiomatic premises of what literature and pleasure can do.

The man in Good Morning, Midnight misunderstands Sasha, but his notion of a generation “mad for pleasure” reflects two truths about the interwar period: that there was widespread suspicion of particular categories of pleasure, and that the broader idea of pleasure itself was undergoing a radical reconceptualization, and nowhere more than in the literary culture of the time. This book will argue that the fundamental goal of modernism is the redefinition of pleasure: specifically, exposing easily achieved and primarily somatic pleasures as facile, hollow, and false, and cultivating those that require more ambitious analytical work. Essential paradigms of modernism, such as the high/low or elite/popular culture divide and the attention to formal difficulty, I claim, revolve around pleasure. That is, the so-called “great divide”7 is fundamentally a way of managing different kinds of pleasure, and modernism’s signature formal rhetorics, including irony, fragmentation, indirection, and allusiveness, are a parallel means of promoting a particularly knotty, arduous reading effect. The discrepancies between the modernist theory and practice of pleasure signal how denigrated pleasures are never actually banished, but are rather presented in a reformulated guise. Focusing on the tension in modernist literature between the artistic commitment to discipline—of ideas, form, and cultural activity—and the voluptuous appeal of embodied, accessible culture, the following chapters will show that modernists disavow but nevertheless engage with the pleasures they otherwise reject and, at the same time, invent textual effects that include daunting, onerous, and demanding reading practices.

In a 1963 essay called “The Fate of Pleasure,” Lionel Trilling contends that “at some point in modern history, the principle of pleasure came to be regarded with … ambivalence.”8 Trilling points to Romanticism as a contrast, exemplified by Keats’s writing (“O for a Life of Sensations rather than of Thoughts”) as well as Wordsworth’s praise in his preface to Lyrical Ballads for “the naked and native dignity of man” that is found in “the grand elementary principle of pleasure” (Trilling, 428). Trilling argues that early twentieth-century writers came to regard sensuous, simple, mainstream pleasures as a false consolation, a “specious good” (445). Conventional bliss, Trilling maintains, did not interest a generation of artists committed to exploring the “dark places of psychology,” as Virginia Woolf put it.9 Trilling describes modernists as a group of writers who “imposed upon themselves difficult and painful tasks, they committed themselves to strange, ‘unnatural’ modes of life, they sought out distressing emotions, in order to know psychic energies which are not to be summoned up in felicity.”10 This, along with the desire to destroy “the habits, manners, and ‘values’ of the bourgeois world” (442), resulted in a full-blown “repudiation” of pleasure (439). While acknowledging that the impulse to look beyond the pleasure principle is not exclusive to the twentieth century—for example, Keats explored a “dialectic of pleasure,” a “divided state of feeling” by which “the desire for pleasure denies itself” (433–434)—Trilling asserts that this impulse to free “the self from its thralldom to pleasure” (445) reached an unprecedented peak in modernism.

Trilling was a great promoter of modern literature as an art of disruption, rebellion, opposition, and crisis. Like any myth, this is in part a distortion. Recent scholarship informed by cultural studies tells another story about pleasure. Instead of Trilling’s brooding, ponderous modernism, we now have a more effervescent one that writes for Vogue, courts celebrity, and adores Chaplin films. Through this lens, even high modernism can look downright user-friendly. However, at the same time that scholars produce a more vernacular, culturally savvy, and accessible field, modernism’s own overt rhetoric about its relationship to pleasure upholds the great divide. Neither Trilling’s “repudiation” nor cultural studies’ enthusiasm exactly captures modernism’s central conflict about pleasure.

While Trilling is right that pleasure is a major preoccupation of modern literature, it is not precisely “bourgeois” pleasure that modern writers purport to reject; nor is the defense against pleasure as straightforward as “repudiation.” To choose two memorable episodes from canonical high modernism, we might think of Leopold Bloom’s breakfast of organ meats at 7 Eccles Street or Clarissa Dalloway’s rumination on her feelings for women that culminates in “some pressure of rapture, which split its thin skin and gushed and poured with an extraordinary alleviation over the cracks and sores!” Notably, these visceral, powerful moments are closely related to negativity and angst, including Bloom’s more representative moods of compulsive avoidance and guilt and Clarissa’s depressing realization that passion is a thing of the past.11 Woolf’s famous remark, inscribed on coffee cups and t-shirts in our own century, “One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well,” is not a rallying cry for the sybaritic life, but rather appears in the context of a discussion of women’s educational deprivation.12 Likewise, the magnificent boeuf en daube scene in To the Lighthouse cannot be read apart from the conflict and violence elsewhere in the novel, which Mrs. Ramsay’s meal only temporarily and partly assuages.13 In modernism, sensual pleasure appears in a climate of tension and fragmentation, only very provisionally transcending rifts and anxieties.

Literary pleasure exists in two related registers: the thematic and the linguistic. As with Rhys’s and Eliot’s texts, the delectation of passages such as the one detailing Bloom’s “nutty gizzards” is generated not only by the objects represented but also by the linguistic play through which they are rendered. The “grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine”14 are hardly epicurean delicacies, although Bloom clearly relishes them. Rather, it is Bloom’s earthy, carnal appetite for “the inner organs of beasts and fowls” and the irony of his delicately wrought tastes (“fine tang,” “faintly scented”) alongside the clinical “urine” that amuse and prepare us for the still more unorthodox appetites to come. Woolf’s luminous prose requires the reader to identify and ponder the collapse of temporality and the associative leaps of consciousness that happen in Clarissa’s moment of illumination. The words themselves, “swollen with some astonishing significance,” effect an ecstatic swoon in the text. The bliss of modernism emerges from highly self-conscious writing that demands a heightened attention to form and the construction of pleasure itself.

Despite its interest in polyphony and suggestion, fragmentation and open-endedness, modernism is highly pedantic insofar as it dictates to readers what kind of enjoyment is permissible. Its assertion of the value of deliberate, intricate, cognitive effort often comes at the expense of more immediate, sensual enjoyment. “Modernism,” Richard Poirier writes, “happened when reading got to be grim.”15 It is worth noting that modernism was at the center of the post–World War One institutionalization of English literature as an academic discipline and a shift away from the study of literature as philology to a field of criticism and interpretation. No longer assumed to be a form of entertainment available to anyone who could read, literature now required professors. It took modernism to constitute literature as a field of inquiry that was, as Terry Eagleton puts it, “unpleasant enough to qualify as a proper academic pursuit.”16 Modernist texts do not appear on summer reading lists: for all its attractions, modernism is no picnic. Its pathways to readerly bliss often require secondary sources and footnotes as dense as the original text. Yet the modernist doxa of difficulty gives rise to new kinds of pleasure. Along with offering thrilling and powerful innovation, modernist writers ask their readers not just to tolerate but also to embrace discomfort, confusion, and hard cognitive labor. Modernism, in short, instructs its reader in the art of unpleasure.

Let me be clear: unpleasure is not the opposite of pleasure, but rather its modification. The concept of unpleasure breaks with the conventional separation of human experience into two tendencies, as expressed in Bentham’s ominous opening of The Principles of Morals and Legislation: “Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. … They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think: every effort we can make to throw off our subjugation, will serve but to demonstrate and confirm it.”17 Unpleasure denaturalizes this distinction between two rival governing bodies and introduces another, less regal category of motivation that operates between them. Unpleasure, from “Unlust” in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, a text written in the shadow of World War One, is characterized by gratification attained through tension, obstacles, delay, convolution, and pain, as opposed to accessible, direct satisfaction. Unpleasure can be grim, but it can also be ironic and funny and offer engagements and intensities on par with pleasure. I will elaborate on the theory of unpleasure later and propose that it offers a dialectical approach to the opposition of pain and pleasure that describes modernist sensibilities. First, though, a note about the parameters of pleasure itself is in order.

The discourse of pleasure is complicated by two long-standing ontological problems. On the one hand, pleasure is exasperatingly unbound; on the other, it remains subject to millennia-old postulates about its nature. Pleasure in general is such an expansive concept that it is useful to begin by estranging ourselves from what we think we know about it. Both second nature and so familiar as to be beneath or beyond definition, pleasure is, as the neurobiologists would have it (in research that postdated modernism), whatever tickles our limbic system or sets our dopamine surging.18 It’s what makes us feel good. We know, to take a page from Potter Stewart, what it is when we see or feel or experience it—we laugh or swoon, or are energized, excited, or riveted. It’s bliss. Ecstasy. Enjoyment. Delight. These near-synonyms all have specialized connotations, but pleasure is semantically unconstrained and apparently ahistorical, although close attention to the way the word is deployed will reveal that one era’s pleasure is not the same as another’s. Geoffrey Hartman contends that “The word pleasure is problematic. … First, for its onomatopoeic pallor, then for its inability to carry with it the nimbus of its historical associations. … Though literary elaboration has augmented the vocabulary of feeling and affect, pleasure as a critical term remains descriptively poor.”19 I find the word itself more evocative than Hartman does: I hear a plosive that relaxes into a sinuous buzz followed by a purr. However, he is right that “pleasure” lacks the connotative richness of words such as jouissance (downgraded to “bliss” in Richard Howard’s translation of Roland Barthes’ Pleasure of the Text); by contrast, the terms that modernists use to dismiss somatic, accessible pleasures are sneeringly effective: the trivializing “fun” or “amusement” and the banalizing “recreation.”

Even as the word is overwhelmingly diffuse, the practice of pleasure has always been kept in tight ethical check. For most ancient Greek philosophers, hedone (pleasure) is only one unruly factor in eudaimonia (happiness). Pleasure is integrally tied to bodily, sensual experience, while happiness is more abstract and metaphysical, correlated with truth, contemplation, and wisdom. A spectrum with asceticism and gluttony at its extremes, pleasure can easily become disruptive, antisocial, or excessive. Pleasure can get out of hand; happiness, never. The relatively recent science of pleasure supports this axiom. In the 1950s, James Olds and Peter Milner embedded electrodes in the brains of rats. When the animals pressed designated levers, the electrodes would deliver local currents. Given the opportunity, the rats with electrodes in pleasure-stimulating areas would press the levers repeatedly, neglecting food, water, and their young.20 Subsequent studies in fields such as affective neuroscience have demonstrated the biological basis of hedonic compulsions and addictions in humans. Many of us are, it seems, only a step away from falling into the vortex of pleasure.

Many early philosophers imagined well-being as a physiological model with two states, pain and pleasure, that need to be balanced in order to achieve ataraxia (tranquility). Only extreme hedonists such as Aristippus of Cyrene (435–356 B.C.E.) declared that pleasure, including immediate and bodily sensation, was the highest good.21 Others, such as Epicurus, were more conservative about indulgence and defined pleasure as aponia (absence of pain) and a lowering of tension. By this logic, pleasure is not intrinsically desirable, but is rather a relief from negative states: a negation of a negation. It is in this spirit that Plato’s Philebus, a dialogue about whether pleasure or reason is the highest good, begins with Socrates’s premise that “the majority of pleasures are bad, though some are good,”22 and proposes a calibration of pleasure according to quality and quantity. Socrates imagines a sort of doorman who chooses to admit pleasures or turn them away: “‘We know about true pleasures,’ we’ll say, ‘but do you also need to share your house with pleasures which are very great and intense?’ ‘Of course not,’ they would probably say. ‘There’s no end to the trouble they make for us: with their frenzied irrationality they disturb the souls we inhabit’” (77). Cogitation, you’re in; lust and gluttony, move along. The aim of pleasure, according to this view, is to eliminate tension and to restore harmony.

Plato also introduced an influential distinction between “true” and “false” pleasures (39), aligning mental pursuits with the former and the pleasures of the body with the latter. A life of physical stimulation without reason, intellect, memory, knowledge, and judgment, Sophocles remarks, is “not the life of a human being, but of a jellyfish or some sea creature which is merely a body endowed with life, a companion of oysters” (16). In contrast to these blissed-out blobs at the bottom of the sea, the highest form of gratification belongs to the philosopher, with his head in the clouds.23 This basic formulation has endured. Bentham’s hedonic calculus was scandalous—“Pig Philosophy,” as Thomas Carlyle put it, giving a mammalian backbone to the oyster metaphor24—because it jettisoned qualitative distinctions: “Prejudice apart, the game of push-pin is of equal value with the arts and sciences of music and poetry. If the game of push-pin furnish more pleasure, it is more valuable than either. Everybody can play at pushpin: poetry and music are relished only by a few.”25 John Stuart Mill refined Bentham’s formulation by reasserting a hierarchy of “higher” and “lower” pleasures that was in keeping with Plato’s hypothesis. “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied,” Mill wrote, and “better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.”26 This hierarchization of pleasure reaches its theoretical zenith in Kantian aesthetics, where rational, universal taste and appreciation are distinguished from embodied, instinctual, voluptuous stimulation.27 Bifurcating experience into a pure (abstract, disinterested) and an impure (sensual, engaged) form exacerbates the semantic problems with pleasure. Adorno points out that “For Kant, aesthetics becomes paradoxically a castrated hedonism, desire without desire.”28 Bourdieu too describes Kant’s “pure pleasure” as “ascetic, empty pleasure which implies the renunciation of pleasure, pleasure purified of pleasure.”29 As paradoxical as the formulation is, it nevertheless became a fundamental principle in articulating a refined aesthetic sensibility, and it underpins modernism’s dismissal of accessible pleasure as facile and trite, and its valorization of that which requires effort and training.

Modernist era philosophy is characteristically contrasted to the crude instrumentalism of utilitarianism, yet the separation of pursuits of the rational mind from sensual, bodily experience proved to be lasting, as philosophers such as G. E. Moore emphasized the cerebral processes or “states of mind” involved in pleasure.30 Modern writers reject the hedonic calculus of utilitarianism and seem to appeal deliberately not to the greatest possible number, but to the least; however, when considering contemporary (vernacular, mass, sensorial) pleasure, modernists substitute their own kind of utilitarian calculus, inverting Bentham’s hierarchy by putting poetry at the top and pushpin at the bottom. Meaningful pleasure is intellectually or aesthetically useful. So Moore, following Plato’s argument in the Philebus, asserts that “pleasure would be comparatively valueless without … consciousness” (92) and that “a pleasurable Contemplation of Beauty has certainly an immeasurably greater value than mere Consciousness of Pleasure” (96). Moore specifies that “pleasure is not the only end, that some consciousness at least must be included with it as a veritable part of the end” (92). Moving valorized pleasure still further from the somatic to the cerebral, Roger Fry writes, in Vision and Design, that “the specifically aesthetic” experience involves an apprehension that “corresponds in science to the purely logical process,” proposing that “Perhaps the highest pleasure in art is identical with the highest pleasure in scientific theory.”31 (Virginia Woolf records Bertrand Russell proclaiming, “I get the keenest aesthetic pleasure from reading well written mathematics.”32) Despite its devotion to aesthetics and beauty and its interest in interior psychological states, most modernism remains largely tethered to aesthetic instrumentalism when it comes to pleasure.

Modernism steers a curious path between Victorian attitudes toward pleasure and those of decadence and aestheticism. Its energies are more in line with the decadent idea of artistic autonomy than they are with the Victorian insistence that art is integrally related to morality; however, modernists consistently frame pleasure as an ethical and aesthetic problem. And while modernism draws from the decadent understanding of the artist’s rarified relationship to pleasure (“Harlots and / Hunted have pleasures of their own to give, / The vulgar herd can never understand,” Baudelaire writes in his epigraph to Les Fleurs du Mal33), decadence, with its swooning sadomasochism, does not typically include the overtly antipleasure rhetoric in which modernism is so invested. What marks the modernist period in the genealogy of pleasure is that unpleasure and difficult pleasure are elevated as aesthetic practices that require extraordinary kinds of reading practices and often entail a hostile relationship to the reader, and that those modes are predicated on a struggle with other—lesser—kinds of pleasure.

Explicated through these categories of value over time, pleasure itself has been strikingly elusive even as it has been a principal term in modern critical discourse. Lord Henry Wotton’s quip, in The Picture of Dorian Gray, that “Pleasure is the only thing worth having a theory about,” sets the tone for a century and a half of exposition about pleasure.34 Just as his “New Hedonism,” at least in the way it is represented in the text, is less about sensual indulgence than about verbal irony, paradox, and coy wordplay, literary critical discourse is dependent upon but largely elides pleasure. In Barthes’s Pleasure of the Text, the primary subject is teasingly vague, and deliberately so. Jouissance, Barthes claims, cannot be put into words; “no ‘thesis’ on the pleasure of the text is possible.”35 Pleasure is thereby relegated to the category of things that are beyond articulation and “can never be fixed directly by the naked eye—let alone pursued as an end, or conceptualized—but only experienced laterally, or after the fact, as something like the byproduct of something else,” as Frederic Jameson has observed.36 This is borne out by twentieth-century cultural critics who have applied themselves to the problem of pleasure as an occasion to discuss something else—for example, politics, censorship, or aesthetics—while never quite registering pleasure’s palpable effects or rendering it as a concrete, immediate, or phenomenological experience. Despite its powerfully specific, local, and stimulating effects, pleasure remains mainly abstract and offstage, a means of getting to another topic rather than something worth pondering for its own intrinsic value.

“We are always being told about Desire, never about Pleasure,” Barthes laments.37 The usually psychoanalytically inflected “desire,” defined by lack and frustration, is much more often the object of analysis than aim-achieving pleasure.38 Desire is compelling, perhaps, because it is, by definition, always seeking, always active, always still unfolding, and hence conducive to analysis. Pleasure, by contrast, is the achieved end point, the need satisfied, the desire slaked. In Slavoj Žižek’s Lacanian terms, for example, the pleasure principle represents limitations, whereas jouissance, or enjoyment, transgresses those limitations.39 Similarly, reflecting on a dialogue with Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze complains, “I can barely stand the word pleasure.” Casting pleasure on the side of dull “strata and organization,” a stabilizing “re-territorialisation” in contrast to desire’s chaotically sexy “zones of intensity,” Deleuze maintains, “I cannot give any positive value to pleasure, because pleasure seems to interrupt the immanent process of desire.”40 Pleasure is, by this assessment, desire’s killjoy. Desire is a work in progress, while pleasure is a narrative punctuation that is also, apparently, the end of theoretical and critical speculation. This is why, for many critics, middle- and lowbrow texts—texts of pandering pleasure (Barthes’s “readerly” text) rather than inscrutable bliss (the “writerly” text)—do not seem to require analysis. Certainly, pleasure has basic sense, brazenly a temporary character, followed by a renewal and repetition. Unlike desire, which can be endlessly attenuated, pleasure is periodic. But in the same way that an orgasm-centered theory of sexuality does not account for vast registers of eroticism, the idea of pleasure as a performance that has ended or a dam that has burst imposes false borders on the experience.

There is something unseemly about pleasure, something too direct, selfish, nonrelational. Hedonism is distinctly out of step with the current theoretical climate of other-oriented, ethical, relational philosophy and cultural criticism. While desire is constantly turned outward, pleasure is, in its most basic sense, brazenly self-centered. We might think of Lacan’s response to Bernini’s sculpture of St. Teresa’s ecstasy. Lacan is sure that “she’s coming [qu’elle jouit], there is no doubt about it,” yet he famously claims that “the woman knows nothing of this jouissance” even while she experiences it, and that despite his “begging” female analysts to disclose the secrets of such pleasure, he got, “well, not a word!”41 Where desire is essentially communicative, discursive, other-seeking, and expansive, pleasure is, on a physical, neural level, a fundamentally insular experience (although it can be shared with others in a mediated fashion). It’s no coincidence that the mystery of pleasure, for Lacan, is symbolized by a woman. Embodied, immediate pleasure has long been aligned with femininity. As we will see, women’s increasing ability to articulate and participate in the discourse of pleasure in the twentieth century is a key development of modernity. In the chapters that follow, I hope to demonstrate that pleasure is every bit as structurally, narratively, and historically complex as desire. The concept of unpleasure amplifies the intricacy of pleasure, as modernists knew well.

MODERNISM’S TIRED TOPOI

Screeds against the “culture industry” in which pleasure is cast as “mass deception” have become familiar parts of modernism. “One of the most tired topoi of the modernist aesthetic and of bourgeois culture at large,” Andreas Huyssen remarks, is that “there are the lower pleasures for the rabble, i.e., mass culture, and then there is the nouvelle cuisine of the pleasure of the text, of jouissance.”42 This tired but tenacious bias is routinely interpreted as a function of the dichotomy between high and low that has, as Robert Scholes notes, “been the founding binary opposition for all Modernist critical terminology.”43 Although it is useful for schematizing modernism’s overt rhetoric about its priorities, this conceptual scaffolding has limitations: the dichotomies inevitably break down, and the scaffolding masks what motivates the dichotomies. As some of the richest work in modernist studies of the past twenty years or so has demonstrated, modernism constantly participates in the vernacular culture (to adopt Miriam Hansen’s nuanced alternative to “popular”44) that it purports to reject. The relationship between modernism and mass or popular culture is more complex than simple opposition, entailing local histories that elude the dichotomy of the great divide.45

So far, so good. However, the same deconstructive analysis has not been applied to pleasure as it structures the terms of the debate. What is fundamentally at stake in the tension between modern literature and vernacular modernism is not just class, aesthetics, or institutions of culture, but even more centrally, judgments about different types of pleasure. That is, distinctions about pleasure are not the by-product of but rather motivate classic articulations of modernist cultural hierarchy. For Q. D. Leavis, for example, the distinction between modern and popular culture is a function of the quality of pleasure each produces. She praises Puritan reading habits and the “extremely subtle kind of pleasure” of the eighteenth century “public prepared to take some trouble for its pleasures,” as opposed to the “immediate,” “cheap and easy pleasures offered by the cinema, the circulating library, the magazine, the newspaper, the dance-hall, and the loud-speaker.”46 All of these amusements have had the effect of diminishing readers’ capacity for tackling challenging texts and appreciating subtle pleasures.

We have no practice in making the effort necessary to master a work that presents some surface difficulty or offers no immediate repayment; we have not trained ourselves to persevere at works of the extent of Clarissa and the seriousness of Johnson’s essays, and all our habits incline us towards preferring the immediate to the cumulative pleasure. (226)

The premise that reading enjoyment requires training beyond literacy itself, and that enjoyment should require serious exertion as well as a tolerance for delayed gratification, is key to Leavis’s argument about cultural value. She notes that “Post-war books are apt to be praised by reviewers and advertised as ‘readable’” (227), as if that is an indictment in itself. If a text is too “readable” it is classified with the easy, accessible, trite pleasures of movies and newspapers. Hence the frequency with which many cornerstones of modernist literature are pronounced “unreadable.” What distinguishes modernist productions from amusement is the effort entailed. Quality pleasure is challenging, flexible, and innovative; inferior versions are ossified and boring, their obvious popular attraction notwithstanding. “Pleasure hardens into boredom,” Horkheimer and Adorno remark, “because, if it is to remain pleasure, it must not demand any effort.”47

Modern fiction writers explicitly address these questions of pleasure’s variable disposition. The following examples display the predictable hierarchies of the great divide, but they also invoke the definition of pleasure and its effects as an essential problem to be solved. This sequence of authors—Lawrence, Eliot, Huxley, and Orwell—indicates the way I am using the term “modernism” here. Not long ago, “modernism” typically only included those authors who practiced radical formal innovation (Pound, Eliot, Joyce, Stein, Faulkner, Woolf, and the like): that is, “high modernists.” However, in recent years, scholars have been expanding the field of inquiry designated as modernism or modernist to include writers from the period who do not experiment extensively with form but who participate in the same ideological discussions. If we prioritize the historical contours of modernism, rather than fetishizing form, as modernists themselves did, the field looks very different. The preoccupation with pleasure is one of the hallmarks of modernity and a means of uniting those authors who are often excluded from canonical modernism but are important figures of the period. Writers such as Lawrence and Huxley, for example, do not engage in the radical aesthetic innovations of high modernism, but they do share many of the signature cultural concerns of the period, and they notably seek to recalibrate their readers’ ideas about pleasure in ways that have surprising affinities with authors such as Joyce and Stein. I present the interwar debate about pleasure and the rise of unpleasure, then, as a new way of defining literary modernism more capaciously.

Near the conclusion of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, a novel that seems consecrated to bodily, immediate delights and that details its protagonists’ every orgasmic stroke, Constance Chatterley travels to Europe, away from her gamekeeper lover, Mellors. She observes tourists in Italy indulging in “Far too much enjoyment! … It was pleasant in a way. It was almost enjoyment. But anyhow, with all the cocktails, all the lying in warmish water and sun-bathing on hot sand in hot sun, jazzing with your stomach against some fellow in the warm nights, cooling off with ices, it was a complete narcotic. And that was what they all wanted, a drug. … To be drugged! Enjoying! Enjoyment!”; “Oh, the joy-hogs! Oh ‘enjoying oneself’! Another modern form of sickness.”48 In this moment, the protagonist’s voice is notably overshadowed by the author’s own near-hysterical expression (recognizable from essays such as “Pornography and Obscenity”). Lest cocktails, sunbathing, and frottage sound too pleasant, Lawrence insists, they are bad! sick! a drug! Lawrence’s authorial presence regularly intrudes on his fictional world when he writes about pleasure, whether he is arguing about the correct form of leisure activity or the correct kind of orgasm for women. His quotation marks (“Oh ‘enjoying oneself’”) appeal to the reader’s sense of semantic distinction and imply that these enjoyments are delusions or a kind of false consciousness.

Some, but not all of these activities are related to mass culture. What bothers Lawrence about cocktails, sunbathing, sexual promiscuity, and jazz, when he believes so passionately in sensual life itself, is that these body-centered activities are effortless, narcotizing, and collective, and decrease awareness. Unlike the forms of eroticism that Lawrence exalts as a means of personal and social enlightenment, a transcending of “sex in the head” that is, paradoxically, very much related to the linguistic expression of consciousness, these modern enjoyments lack any purpose except pleasure. The most threatening pleasures are tautological, with no “added value.” They “mean,” as Aldous Huxley writes of the “feelies” in Brave New World, only “themselves; they mean a lot of agreeable sensations to the audience.”49 Art for art’s sake is a worthy endeavor, but not pleasure for pleasure’s sake. T. S. Eliot makes a similar point in his 1934 essay on “Religion and Literature,” where he investigates the attraction of popular literature.

I incline to come to the alarming conclusion that it is just the literature that we read for “amusement,” or “purely for pleasure” that may have the greatest, and least suspected influence upon us. It is the literature which we read with the least effort that can have the easiest and most insidious influence upon us. Hence it is that the influence of popular novelists, and of popular plays of contemporary life, requires to be scrutinized most closely. And it is chiefly contemporary literature that the majority of people ever read in this attitude of “purely for pleasure,” of pure passivity.50

According to this view, popular contemporary literature surreptitiously bypasses consciousness and obviates effort. The same argument, as we will see, was made about cinema, which was thought to lower people’s defenses, lulling them into a relaxed or hypnotized condition. Again, ironic quotation marks around the operative terms “amusement” and “pleasure” suggest that Eliot, like Lawrence, views the sociological problem of pleasure as importantly related to language. Modern writers confront pleasure from within language itself, by advocating closer textual scrutiny and pressing the word to signify not one but several different ranks of phenomena. (“Life is a well of joy,” Nietzsche wrote, “but where the rabble drinks too, all wells are poisoned. … They have poisoned the holy water with their lustfulness; and when they called their dirty dreams ‘pleasure,’ they poisoned the language too.”51) Such self-consciousness and linguistic defamil-iarization are standard modernist strategies. This is not just irony, but an attempt to subject the sensation of pleasure to the same concerns modernists voice about aesthetic experience.

Although they would have been loath to admit it, modern writers, in these arguments for the necessity of putting more effort into amusement, overlapped significantly with contemporary “leisure theorists”: philosophers and social scientists who emphasized the importance of pursuing cultivated pleasures as a bulwark against cultural degeneration. The popular (and anti-Bloomsbury) philosopher C. E. M. Joad, whose misogynist writings Woolf cites extensively in Three Guineas, argues in his 1928 tract Diogenes or the Future of Leisure against easy, popular pleasures in favor of activities and tastes that “must be worked for; they must be pursued with effort and through boredom.” Labor and difficulty, Joad claims, are exactly what the modern situation requires. Our cultural development depends on our willingness to shun simple, easy pleasures, forsaking “festering on the beach at Margate” (23) for reading “good novels” (25) and other challenging pastimes. If, Joad maintains, we “force ourselves to undergo a severe training,” we will “enjoy the happiness which comes to all who struggle.”52

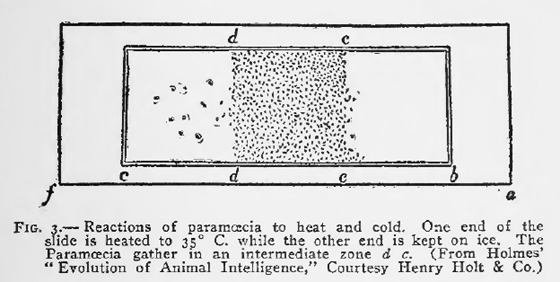

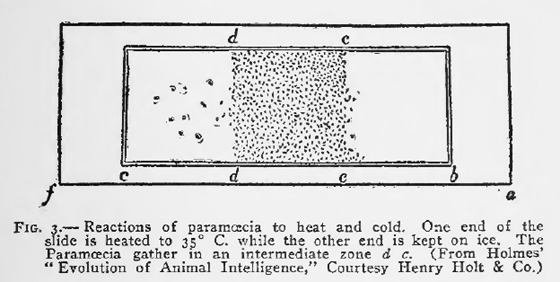

“Reactions of paramoecia to heat and cold” from Henry Thomas Moore, Pain and Pleasure, 1917.

Henry Thomas Moore’s treatise on Pain and Pleasure (1917) makes a similar point by invoking experiments on single-celled animals: for example, paramecia put in a trough with progressively freezing to very hot water were found to gravitate toward the pleasant, tepid temperatures in the middle. Humans must distinguish themselves from such lowly creatures, Moore argues, by striving to develop more complex and demanding inclinations. Moving from the petri dish to the concert hall, Moore contends that the most worthy pleasure must be cultivated and “results from conflict.”

The music that we most enjoy to-day would have been laughed out of court as unspeakably disagreeable two hundred years ago. More and more dissonant intervals have challenged the ears of each successive generation, and while each new innovation has created confusion and unpleasantness, it has been gradually mastered by the music-going public, which now demands that music be complex and even harsh in order to be enjoyable.53

Confusion, unpleasantness, complexity, and harshness are positive values. Aesthetic enjoyment is figured as a punishing series of hot and cold plunge pools (as opposed to the paramecia’s bath or Lawrence’s “warmish water”) that stun the mind awake. This is art as shock therapy. Moore is more optimistic than Eliot, Lawrence, and Huxley in his conviction that people can be and are being trained to value more difficult pursuits. Among modernist literary critics, there is a shared sense of despair that amusement is winning the war on pleasure.

Huxley’s 1923 essay called “Pleasures” is a particularly despondent dispatch from the front:

Of all the various poisons which modern civilization, by a process of auto-intoxication, brews quietly up within its own bowels, few, it seems to me, are more deadly (while none appears more harmless) than that curious and appalling thing that is technically known as “pleasure.” “Pleasure” (I place the word between inverted commas to show that I mean, not real pleasure, but the organized activities officially known by the same name) “pleasure”—what nightmare visions the word evokes! … The horrors of modern “pleasure” arise from the fact that every kind of organized distraction tends to become progressively more and more imbecile. … In place of the old pleasures demanding intelligence and personal initiative, we have vast organizations that provide us with ready-made distractions—distractions which demand from pleasure-seekers no personal participation and no intellectual effort of any sort. To the interminable democracies of the world a million cinemas bring the same balderdash. … Countless audiences soak passively in the tepid bath of nonsense. No mental effort is demanded of them, no participation; they need only sit and keep their eyes open.54

Huxley starkly juxtaposes “old” pleasure—“real pleasure” that is individualized and intellectually demanding—with “ready-made,” collective, and immediate distractions (described, once again, through the metaphor of the warm bath). Mindfulness and individualism are the supreme virtues that separate humans from beasts. For Huxley, there is something especially disturbing about the creation of pleasures that materialize as effortlessly as waste brewed in modern civilization’s bowels. (It is not just their novelty that bothers Huxley; he is more approving of the engineered phenomenon of speed, which he claims in a 1931 essay “provides the one genuinely modern pleasure.”55 Unlike more complex forms of culture that require explanation and effort, the production of these new pleasures is just as automatic as their consumption. Old pleasures, by contrast, are hard to achieve and require education to create and properly digest.

In metaphors from the barnyard to the pharmacy, from Q. D. Leavis’s descriptions of the consumption of vernacular culture as masturbation or a drug habit56 to the Frankfurt School critique of “distraction factories,”57 passive and corporeal pleasures—often associated with femininity and with the new sensorium—are posited as inferior to the deliberately chosen, cerebral, and difficult pleasures of modernism. All of the aforementioned attacks on pleasure are predicated on challenging the dominant idea of the word itself. (Orwell’s 1946 essay “Pleasure Spots” sounds the same notes: “Much of what goes by the name of pleasure is simply an effort to destroy consciousness. … The tendency of many modern inventions—in particular the film, the radio and the aeroplane—is to weaken [man’s] consciousness, dull his curiosity, and, in general, drive him nearer to the animals.”58) Signposts around pleasure set off the writer’s sensibilities from common usage, a recurrent rhetorical maneuver that is further evidence that modern writers thought of pleasure not merely as a matter of what people did with their spare time, but as a potential threat to language itself that needed to be fought, in kind, through language. Hence, modern writers managed their readers’ response to pleasure and actively inscribed their own alternatives into the grain of their writing.

DIFFICULTY AND UNPLEASURE

“We do not take pleasure seriously enough,” Robert Scholes remarks, “and Modernism, with its emphasis on the connection between greatness and difficulty, is to some extent responsible for this” (xiii). Significantly, we have elaborate analyses of the anatomy of difficulty—for example, William Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity or George Steiner’s “On Difficulty”59—but no equivalent for pleasure. In tandem with disparaging embodied, accessible pleasure, modernists revise the conventional relationship between the artist and the audience from entertainment to intellectual challenge. The hallmarks of modernism—including fragmentation, disjunction, and irony—are strategies that demand interpretive work from the reader as well as a certain kind of tolerance and submission.60 Trilling observes that

Our typical experience of a work which will eventually have authority with us is to begin our relation to it at a conscious disadvantage, and to wrestle with it until it consents to bless us. We express our high esteem for such a work by supposing that it judges us. … In short, our contemporary aesthetic culture does not set great store by the principle of pleasure in its simple and primitive meaning and it may even be said to maintain an antagonism to the principle of pleasure. (438)

The reader genuflects before an arrogant, hostile text. Here Trilling presupposes a combative or masochistic model of readership, an engagement with an arrogant opponent that will eventually be enriching. This is very different from collaboration or seduction, more conventional conceptual models of readership. Indeed, modernism has a confrontational edge: Eliot’s insistence that “poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult,”61 for example, or Dorothy Richardson’s quip that “Plot, nowadays, save the cosmic plot, is inexcusable. Lollipops for children.”62 Joyce’s only half-joking claim that “the demand that I make of my reader is that he should devote his whole life to reading my works” is confirmed by his prose, which seems to have been written for an “ideal reader suffering from an ideal insomnia.”63 Difficulty becomes an inherent value and is a deliberate aesthetic ambition set against too pleasing, harmonious reading effects. Conventional pleasure is dismissed precisely because it is too easy and seems to pander to the dumb happiness of beasts.

Rather than become more conventionally captivating, modernists invented new modes of engagement. Against the saccharine, predictable, easy amusement of popular novels, newspapers, and cinema, they offered cognitive tension, irony, and analytical rigor. Leonard Diepeveen has made a convincing case that when disparaged for “block[ing] reading pleasure, creating anxiety and irritation instead,” modernists claimed that the struggle with difficult texts had its own intrinsic rewards: the satisfaction of solving a puzzle or recognizing arcane references, sorting out the voices of The Waves, or decoding Pound’s Cantos.64 Those of us who have to coax recalcitrant undergraduates into reading Ulysses will recognize this argument: really, it’s FUN.

An important motivation for modern art’s aesthetic difficulty was competition with the undeniable charms of vernacular culture. In Orwell’s 1936 novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying, which wittily stages the cultural battle of the brows in a bookshop scene, the self-defeating would-be poet Gordon Comstock is undone by his attempt to compose a massive work in rhyme royal, an Eliotic pastiche caustically called “London Pleasures.”65 Gordon sneers at the common urban pleasures around him even as he acknowledges their allure:

The pubs were open, oozing sour whiffs of beer. People were trickling by ones and twos into the picture-houses. Gordon halted outside a great garish picture-house, under the weary eye of the commissionaire, to examine the photographs. Greta Garbo in The Painted Veil. He yearned to go inside, not for Greta’s sake, but just for the warmth and the softness of the velvet seat. He hated the pictures, of course, seldom went there even when he could afford it. Why encourage the art that is destined to replace literature? But still, there is a kind of soggy attraction about it. To sit on the padded seat in the warm smoke-scented darkness, letting the flickering drivel on the screen gradually overwhelm you—feeling the waves of its silliness lap you round till you seem to drown, intoxicated, in a viscous sea—after all, it’s the kind of drug we need. (71–72)

Here we see, in characteristic Orwellian clarity, anxiety about cinema’s appeal (such bad food and such small portions!), felt all the more now that cinema was superseding or cannibalizing literature. Unlike Graham Greene’s sociopathic Pinkie in Brighton Rock, who has an extreme antipathy to somatic enjoyment—dancing, alcohol, and sex fill him with “the nausea of other people’s pleasures”66—Gordon senses but tries to resist the cinema’s “soggy attraction.” Gordon is a comical failure whose negativity and pretentious rebellion keep him from enjoying anything. Orwell understood the power of “good bad books”67; nevertheless, like Huxley, Eliot, and others, he articulates the common concerns about vernacular culture here and in 1984, where he imagines a dystopia that secures its drone-citizens’ compliance through “pornosec” and fiction produced by “novel writing machines.” The new landscape of vernacular pleasure is both stimulating and threatening to modern writers, as evidenced by the defensive mode that often underlies their seeming autonomy and innovation.

Diepeveen contends that

high moderns moved too briskly away from mainstream notions of pleasure. Looking askance at forms of pleasure that didn’t have its vigorous ethic attached to it, difficult modernism presented the hard and serious work required for reading Ulysses as the only worthwhile pleasure. Thus, even though difficult modernism shed light on an important aspect of art when they described difficulty’s anxiety, and why that anxiety might be important, it was less adept at imagining the validity of other forms of pleasure. … When they asserted their vigorous morality, difficulty’s apologists also couldn’t deal with the pleasure of physical abandonment and sensual indulgence. (173)

This kind of pleasure, Diepeveen argues, is modernism’s “blind spot.” Certainly, modernism privileges serious cultural work, but its resistance to vernacular and sensual pleasures suggests that it is anything but blind to them—rather, it never takes its eyes off them. The writers collected here often draw on simple, immediate pleasures, but present them through devices of refinement, indirection, irony, and distance that mitigate against a reader enjoying them too easily or too much. Modernism’s contribution to the genealogy of pleasure is the declared substitution of one set of pleasures (refined, acquired, and cognitive) for another (embodied, accessible), in which the disavowal of the latter is promoted as an aesthetic principle. The construction of pleasure hierarchies, the resistance to certain stimulation, and the obstacles to reading pleasure, culminate in their own kind of contorted satisfaction.68 (This did not only happen in literary modernism: there was a concomitant problematicizing of pleasure in fine art as abstract, nonmimetic modernist and avant-garde works challenged traditional conceptions of art and the experience of viewing it. Clement Greenberg, for example, in his influential 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” contrasts the ersatz culture of kitsch, “vicarious experience and faked sensations,” to “what is necessarily difficult in genuine art.”69) This premise has been one of modernism’s enduring cultural legacies: the philosopher Susanne Langer argued that “Now that everyone can read, go to museums, listen to great music, at least on the radio, the judgment of the masses about these things has become a reality and through this it has become clear that great art is not a direct sensuous pleasure. Otherwise, like cookies or cocktails, it would flatter uneducated taste as much as cultured taste.” Modernism is the first moment when “great art” so consistently asserted formal experimentation and allusiveness—pleasure and unpleasure that had to be learned—and withheld from its audience cookies and cocktails.70

What, then, should we call this aesthetic response that must be earned or learned, and that distinguishes itself from facile amusement? Commenting on the reading experience of The Waste Land, Frank Kermode detects a “pleasure that is accompanied by loss and even dismay—something quite different from the ordinary pleasures of reading … an experience hardly to be called pleasure, a moment of ecstatic dismay.”71 Ecstatic dismay is a suggestive description, but not wide enough to cover the range of dysphoric effects in modernism. Earlier writers had anecdotally described the paradoxical attraction of unpleasant experiences (itching for Plato, ecstatic martyrdom for the early saints, spanking for Rousseau, the sublime for Kant), and late nineteenth-century sexologists such as Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis catalogued masochistic and sadistic practices in the realm of human sexuality that blurred the distinction between pleasure and pain. But it was Freud who moved the discussion to more general principles of psychology, offering in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) a metapsychological theory of “Unlust,” translated as unpleasure, which unmoors the premise that people seek pleasure and avoid pain. Unpleasure (as distinct from “Schmerz,” or “pain,” which Freud uses to designate more uniform negative experiences72) is not an abdication of pleasure entirely, nor is it the same as anhedonia. “Lust” is embedded in “Unlust,” and this is key to grasping the relationship between the two drives. Recasting the classical model of pleasure as a lessening of tension—“unpleasure corresponds to an increase in the quantity of excitation and pleasure to a diminution”73—Freud describes enactments of “unpleasurable tension” such as the repetition compulsion that circuitously produce pleasure. Here, as a dialectical resolution of apparently oppositional forces, unpleasure is useful for describing the modernist approach to pleasure. That Freud elaborated the concept of unpleasure in the context of interwar culture strengthens its aptness for literary modernism and demonstrates further how views about pleasure are subject to historical fluctuations.

The force of Beyond the Pleasure Principle is its suggestion that people commonly seek out convoluted and distressing experiences, and that what seems like pain or unbearable conflict can produce pleasure. Leo Bersani has drawn out the implications of Freud’s argument about “the pleasureable unpleasurable tension of sexual excitement” to suggest that “The mystery of sexuality is that we seek not only to get rid of this shattering tension but also to repeat, even to increase it. … Sexuality—at least in the mode in which it is constituted—could be thought of as a tautology for masochism.”74 Far from a perverse experience, unpleasure can be part of commonplace experience, and not just in the sexual realm. The reality principle itself, Freud maintains, requires “the temporary toleration of unpleasure as a step on the long indirect road to pleasure” (Beyond the Pleasure Principle, 7). Sublimation itself is a form of unpleasure.

Freud’s idea that we must renounce what we actually want (presented, for example, in Civilization and Its Discontents) is useful for complicating what Trilling deems modernism’s “repudiation” of pleasure. The fort/da game of Beyond the Pleasure Principle, which Freud calls “the child’s great cultural achievement—the instinctual renunciation (that is, the renunciation of instinctual satisfaction)” (14), a ruse of postponement and simulated control that masters emotional attachment to the mother, is suggestive of modernism’s distrust of instinctive, comforting, bodily pleasure and its validation of difficulty. What may look like a suppression of sensual, embodied, immediate, and easy pleasure in the service of cognitive effort is a means of assuaging an attraction to those disavowed pleasures. Modernism redefines pleasure not just to include but to require tension, difficulty, and obstacles. Unpleasure, to adapt Bersani, may be a tautology for modernism.

“Unpleasure” is a big umbrella. How is it different from, say, the sublime’s pleasurable terror? While the sublime taps into deep instinctive impulses (the natural sublime is involuntary, although it can then be consciously constructed in literature), the modern repudiation of pleasure must be cultivated and learned. With authors like Joyce, Rhys, and Patrick Hamilton, terms such as “masochism,” “abjection,” or “jouissance” are plausible explanations for some of the experiences they describe. However, these are only subsets of a broader category. I will use “unpleasure,” then, as it reflects the self-conscious and explicit interwar discourse about pleasure. More than any other term, “unpleasure” is able to encompass both the complex, dialectical representations of pleasure and the readerly affects modernism puts into play.

READING FOR (UN)PLEASURE

Laura Mulvey famously declared, in “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” “It is said that analysing pleasure, or beauty, destroys it. That is the intention of this article.”75 The intention of this book is the opposite. It is, rather, to analyze, magnify, and participate in the varieties of delight and unpleasure that texts display. How should we go about grasping pleasure? How can we catch it in the act? First, we have to move past the idea that pleasure must be veiled or obscure: an affect that dare not speak its name. While it is true that analyzing pleasure, like analyzing jokes, runs the risk of ruining the fun (hence, Beyond the Pleasure Principle is really no more pleasurable than Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious is funny), it is a risk worth taking. The linguistic barriers to sense impression mean that pleasure is always and necessarily mediated in literature. Recent studies such as Sianne Ngai’s Ugly Feelings and Lauren Berlant’s The Female Complaint have provided useful models for reading the aesthetic, political, and social implications of affect, and I will follow their lead in conceptualizing pleasure as a bodily, individual experience that is simultaneously located in a social field as well as, most importantly, a textual one.76 The challenge of analyzing pleasure rendered in language lies in teasing out its texture and effects: its ticklish play on the page, its moments of affectual intensity, the “fire and wings” in Good Morning, Midnight, for example, or in Katherine Mansfield’s short story “Bliss” (1920), the protagonist’s sensation that she’d “suddenly swallowed a piece of that late afternoon sun and it burned in [her] bosom, sending out a little shower of sparks into every particle, into every finger and toe.”77 Such moments solicit the reader’s feelings and body through both the objects or states represented and the language itself. A text of bliss, Barthes writes, must “cruise” its reader (4); “whenever I attempt to ‘analyze’ a text which has given me pleasure … it is my body of bliss I encounter” (62). The text does not have to be a sensation novel; this happens when we admire a felicitous phrase, laugh, are aroused, or find ourselves drawn in through textual challenges, mysteries, or riddles. Of course, a text can appeal to different readers in different ways, so the focus here is primarily on the rhetorical management of pleasure for what Wolfgang Iser has called an “implied reader.”78 We do not read modernist works now in exactly the same way readers did in the 1920s and ’30s. Retrieving that experience is impossible, but the author’s linguistic cues give a strong sense of what kind of response was expected and desired. Barthes insists that pleasure is never so obvious as to be literal—“the text of bliss is never the text that recounts the kind of bliss afforded literally by an ejaculation. The pleasure of representation is not attached to its object”—but rather is linguistic and “occurs in the volume of the languages” (55, 13). This conforms to modernism’s own story about itself (nothing so low as representational pleasure: but can one cruise without a body?), but it is not the whole story. Modernism simulates or curtails pleasure—thematically and linguistically—in order to achieve a particular effect. So Mansfield’s story, for example, is both a catalogue of sensations and a text of aporias, ellipses, and indirection that reflects the incoherence of her protagonist’s feelings and demands an analytical and mediated kind of engagement. Reading for modernist pleasure, then, requires an attention to how a text represents, produces, and thwarts bliss at once.

For all its elusiveness, modernism is profoundly pedagogical. It continually teaches readers how to approach its texts. Modernist fictions are full of implied or explicit injunctions—notice this, admire this, reject this, puzzle over this—and scenes that model correct and incorrect readerly affect. So Joyce, for example, exhibits and creates models of different kinds of pleasure—readerly, aesthetic, and sensuous—in Ulysses. Lawrence, through overt polemic and textual guidance, aims to shape his audience’s experience of reading and of sexuality together. Stein trains her reader to tolerate repetition and indeterminacy. Huxley expounds on the idea that people’s pleasures can be upgraded through pedagogy and other modes of cultural conditioning.

That said, in modernism, pleasure is often the place where the text contradicts itself. Pleasure may exert itself through ideology-defying magnetisms and irrational attractions. It is important to note an author’s avowed stance but also to pay close attention to how pleasure plays out in the text. Barthes writes, “The pleasure of the text is that moment when my body pursues its own ideas—for my body does not have the same ideas I do” (17). Although modernists attempt to tightly control their effects, scorned delights appear everywhere in disguised or disavowed forms. So, for example, the language that Lawrence uses when he writes about eroticism makes use of the same clichés and stereotypes that he condemns in popular genre fiction; and when Huxley depicts Brave New World’s pneumatic woman Lenina Crowne, he appeals to the same prurience that he abhors in popular culture. Modernists often use, in the guise of irony, the same formulas of vernacular culture that they otherwise reject as corrosive precisely for the attractions they offer. Pleasure is often where the text goes beyond or gets away from itself.

It is not my goal here to account for all kinds of subjects responding to all kinds of pleasure, but rather to suggest, through a series of heuristic readings, how centrally modern literature is concerned with the reconceptualization of pleasure. In the following chapters, I will analyze stimulants as diverse as perfume, bearskin rugs, Rudolph Valentino, and linguistic puzzles, and experiences ranging from wordplay to foreplay to tickling to drunkenness. Widening the field to include both somatic and cognitive pleasure and to show the imbrication of the two is a strategic choice that I hope will reflect unexpected connections, combinations, transfer points, and associations between and among different types of pleasure.

I aim to capture a panorama of pleasures while emphasizing those about which modernists were most overtly concerned. It was an era shadowed by the Great War and the impending signs of another; it was also a time of gender upheaval and novel forms of mass culture: the disembodied sounds of the radio, the gramophone, and interwar cinema’s momentous transition from silence to sound. The “mass production of the senses,” Miriam Hansen writes, offered “new modes of organizing vision and sensory perception, a new relationship with ‘things,’ different forms of mimetic experience and expression, of affectivity, temporality, and reflexivity, a changing fabric of everyday life, sociability, and leisure” (60). This mass production initiated modes of pleasure and means of stimulation that troubled as well as excited modernists. This is not merely about the invention of new technologies or a shift in perception or cognition: it is about shifts in the value of particular pleasures and the understanding of how modernity is experienced through the body and the brain, and also how those shifts impact aesthetics. If, as Walter Benjamin remarked, “technology has subjected the human sensorium to a complex kind of training,”79 literary modernists counter this with their own kind of training in reading that ratifies certain pleasures as legitimate and casts doubt on others. There is a thread running through these chapters about emergent technology facilitating this effortlessness, in which machines do not so much alienate (like the gears and gadgetry of Chaplin’s Modern Times, for example) as they generate easy, debased, bodily pleasure. Modernist prose is the opposite of technological efficiency. It means to discomfit its readers, to make them focus, think, and grapple with language. It is conspicuously labor intensive.

There are two strong currents running through the dominant representation of pleasure in modernism. Literary modernity corresponded to the emergence of women as politically empowered subjects and also to the establishment of cinema, newly imbued with sound, as a massively popular pastime. Female voices and the cinema, both figured as intensely somatic and largely noncerebral, are often the foil for modernist unpleasure. The twentieth-century equivalents of Bentham’s pushpins were popular women’s novels and films. In the late 1920s and early ’30s, modernists continually focused on the nexus of popular fiction—which Lawrence personifies and pointedly feminizes as “that smirking, rather plausible hussy, the popular novel”80—and cinema as a site of controversial pleasure.

My focus here has been necessarily selective, and this project largely addresses British modernists as well as some American writers. All of them, however, were strongly influenced by other national literatures, and most spent substantial amounts of time living outside of their native countries.81 Their work therefore offers a more cosmopolitan vision of pleasure than their national origins might suggest. Mapping complex linguistic traditions and nationalities onto a concept like pleasure is a complicated matter. Pleasure is typically experienced as an individual, local, and intimate event, but affiliations of race, class, gender, and nationality all exert an influence over how and where particular pleasures flourish. The dominant discourse of bliss has been largely Western, white, male, privileged, and heterosexual. Female Harlem Renaissance writers such as Nella Larsen or Zora Neale Hurston, for example, had a different set of political pressures around their representation of pleasure than did white, male, British writers such as Huxley, Lawrence, or Patrick Hamilton.82 This study never loses sight of that fundamental difference, but I also argue that Huxley’s treatment of the black male body, Lawrence’s orientalist sheiks, and Hamilton’s prostitutes, among other examples, illustrate how stereotypes of race, gender, and nation shape pleasure.

Most criticism on the modernist sensorium focuses on visual or auditory pleasure. I begin with the less considered realm of olfaction. Chapter 1, “James Joyce and the Scent of Modernity,” examines one of modernism’s great hedonists who is also one of the great artists of unpleasure. Numerous odors, fragrant and foul, waft through Ulysses, charged with erotic and mnemonic symbolism. For Joyce, odor is significant because it hovers on the threshold between body and mind, confounding the bifurcation of these qualities in contemporary theories of pleasure. Odor in general has a formal dimension: its dispersal is analogous to the mechanisms of the mind that produce involuntary memory and stream of consciousness. Perfume would seem to embody the simple, somatic pleasures against which high modernism often sets itself, but Joyce is also interested in the cultural connotations of perfume, and especially the synthetic creations of modern perfumery, which strikingly dovetail with the history of aesthetic modernism. Modern perfume’s most compelling qualities, for Joyce, are its contradictions: its combination of artificial and natural scents, its abstract and mimetic characteristics, and its blend of the putrid and pleasing. Perfume is a metaphor for Joyce’s response to pleasure in general. His “perfumance” in Ulysses,83 which includes inventing his own fragrance, “Sweets of Sin,” poses counterintuitive acts of olfactory pleasure as a model of eroticism and readership that seeks to expand his audience’s repertoire of sensation in idiosyncratic ways.

Chapter 2, “Stein’s Tickle,” takes up one of the outstanding questions in Stein criticism: how and whether she gives pleasure. There has been a strong turn in recent Stein criticism toward interpreting her as a purveyor of sensuous pleasure that is secured by her hermeticism and indeterminacy. That is, the same formal features in her work that are deemed irritating or confusing have increasingly been read as the source of her appeal. Looking at Stein’s experimental writing from 1914 to her lectures of the mid-1930s, I will suggest a new model for approaching her work: tickling. Both infantile and erotic, delight-inducing and irritating, physically reflexive and intersubjective, tickling is an enduring social and scientific mystery whose patterns, I will argue, illuminate Stein’s methods and her reading effects. The gesture of tickling describes both the delights and difficulties of Stein’s texts and also accounts for the wide discrepancies in readers’ responses to her writing.

Chapter 3, “Orgasmic Discipline: D. H. Lawrence, E. M. Hull, and Interwar Erotic Fiction,” considers the relationship between innovation and repetition in the structure of pleasure, and Lawrence’s effort to direct readerly pleasure around those poles. For most modernists, vernacular culture has its own language: cliché, stereotype, and banal formula, all of which would seem to work against the modernist maxim to “make it New.” Lawrence’s representation of sexuality is understood to be among the most original of the modernist period. However, just as British genre novels and popular films exerted an important influence on many modernist representations of sexual pleasure, Lawrence criticized but also borrowed from the formulaic language of popular romance by turning it toward antierotic purposes. I will examine Lawrence’s charged reaction, in his essays and in fiction, to E. M. Hull, whose 1919 novel The Sheik was the supreme interwar desert romance novel. Lawrence’s appropriation and manipulation of Hull’s work demonstrates how circuits of pleasure favor both novelty (the shock of the new) and familiarity (the sure thing). Lawrence’s effort to actively reform pleasure is most evident in his strategies of orgasmic discipline, through which he demands that his characters, along with his readers, embrace arduous ecstasy.

Chapter 4, “Huxley’s Feelies: Engineered Pleasure in Brave New World,” considers Huxley’s most famous novel as an intricate balance of pleasure and unpleasure. Huxley highlights the management of vernacular pleasure in Brave New World as a means of bolstering other techniques of social and political conditioning. In so doing, he addresses one of the central assumptions of modernism: that pleasure can be manipulated and upgraded through training. Huxley is interested in the ways pleasure is malleable and the uses to which it can be put, and he casts the cinema as a key manifestation of engineered pleasure. His response to early cinema—and especially the transition to sound—recognizes its stimulation of the body as well as the mind and imagines film’s potential to be either an instrument of sociopolitical reform or a medium of cultural degeneracy. This chapter traces the dense composite of references around the “feelies” in Brave New World, from a popular women’s romance novel to Shakespeare to race cinema and nature documentaries. Just as Lawrence’s work registers the attraction of the material he claims to reject, the engineered pleasures in Brave New World, including the feelies, exert a frivolous, sleazy magnetism that often contradicts the novel’s argument against careless hedonism. The totalitarian culture that is meant to be repellent is secured by a wide variety of vernacular pleasures that are, from a readerly perspective, paradoxically engaging. This irony is extended in Huxley’s subsequent adaptation of Brave New World to the form that is perhaps least likely: a musical comedy.

If some modernists foreground cognitive and aesthetic difficulty in their work, others replace conventional, sensory, popular, and stereotypical enjoyment with forms of somatic and aesthetic unpleasure that are contorted, violent, or masochistic. Chapter 5, “The Impasse of Pleasure: Patrick Hamilton and Jean Rhys,” pairs two late-modernist authors who are rarely thought of as pleasure seekers but rather as chroniclers of urban misery. Like other writers of the period, Hamilton and Rhys are highly attuned to vernacular culture as the main force of conventional, bodily pleasure. However, in fictions in which the losses of the Great War and the menacing rise of fascism are felt, these authors extend the critique of pleasure in a new direction as vernacular culture becomes the primary realm for their protagonists to achieve negative distinction. Effacing the conceptual boundaries between pleasure and pain, Hamilton and Rhys deploy several common vehicles—including alcohol, cinema, and prostitution—to redefine the texture and terms of the pleasure principle and to show the allure of intense experience that is obliterating, repetitive, and self-destructive. Through representations of visceral distress, dark humor, and characters of determined dissolution, Rhys and Hamilton both frustrate reading for pleasure and beckon their audience to read for unpleasure.

Chapter 6, “Blondes Have More Fun: Anita Loos and the Language of Silent Cinema,” turns to an author for whom the modernist debate about pleasure is a source of amusement, creativity, and aesthetic play rather than a vexing problem and who, in this respect, anticipates the movement beyond modernism, postmodernism. Loos’s 1925 best-selling novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was simultaneously lambasted by Q. D. Leavis and Wyndham Lewis and praised by pleasure critics such as Huxley and Mencken. Blondes’s appeal to modernist audiences turns on the way Loos develops a linguistically witty and self-conscious reading pleasure within one of the most reviled of the interwar genres: popular women’s writing and film. Loos honed her linguistic strategies in the early silent cinema writing screenplays and subtitles, which until that point had been largely dismissed as superfluous and artless: a means of making an undemanding art form even more effortless. At a transitional moment when literary institutions were changing and the cinema was being born, Loos cross-pollinated the novel with the cinema to invent new forms of vernacular pleasure and slyly demonstrated how acts of cultural classification (and their undoing) are themselves pleasurable. Along the way, she sends up the pretentions of modernist pedagogy, asserting the possibility of witty innovation without the vexation of unpleasure. For these reasons, I position Loos as a transitional figure out of the thicket of modernism into postmodernism.

The book concludes with a coda, “Modernism’s Afterlife in the Age of Prosthetic Pleasure.” Although summing up six decades of pleasure after modernism is impossible, by way of a necessarily impressionistic conclusion, I will look at David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest (1996), as it demonstrates how, despite postmodernism’s divergence from many of modernism’s premises, the conception of pleasure as a problem remains strong into our century.

My goal is to place pleasure at the center of the twentieth century and to cast the history of literary modernism in a way it has not been seen before: as a tumultuous and revealing chapter in the history of bliss. Although this book investigates the counterintuitive condemnation of experiences of delight and enjoyment as a discursive issue in modernism, my fundamental premise is hedonistic. No matter how circuitous the paths may be, there is, in every aesthetic act, a basic impulse toward an engaged incitement, but we need to expand and even revise our concept of pleasure in order to perceive that effect throughout modernism. What looks like a story about limiting pleasure, then, is also a story about its proliferation.