During the Iron Age II period, the sociopolitical situation was completely different to previous periods. The United Monarchy, and the separated kingdoms of Israel and Judah, developed administration systems that superseded tribal authority. As a consequence, the armed forces and the principles of defence changed as well. Each state now possessed an army composed of local levies and more consistent mercenary forces. The Israelites developed the urban strongholds of the once mighty Canaanite cities of the Bronze Age (Laish-Dan, Hazor and Megiddo in the north, Jerusalem and Lachish in the south), and created new ones (Samaria and Jezreel in the north, and Arad in the south). The smaller Israelite settlements of the Iron Age I period grew in size too. There was a clear hierarchy among such settlements, from the capital cities of Samaria and Jerusalem, through the administrative centres of Megiddo, Hazor, Lachish, and Beer-sheba II, to the small provincial towns, such as Tell Beit Mirsim.

The Israelite cities built during the Iron Age II period followed clear planning principles. The three main ones were peripheral planning, radial planning and orthogonal planning. The outer contour of the settlement and the natural surface conditions of the site were important criteria at the planning stage. In settlements characterized by peripheral planning (the most common form, of which Megiddo is the best example), the line of the wall is planned in accordance with the topography of the terrain, but houses are built without any uniform plan. However, in settlements characterized by (the much rarer) radial planning (of which Beer-sheba, Stratum II is a good example), the radii emanating from the central point appear to determine the plan of the settlement.

Orthogonal planning is characterized by the use of the square and a lack of conformity to the natural contours of the site. Many such settlements thus stand out from the surrounding area, giving them a monumental character. It requires great engineering, such as levelling and quarrying work, as more often than not the spot chosen does not present the square contour required. This type of plan was implemented at settlements of social, political or military importance such as an acropolis, a capital city, or a main administrative centre. Good examples of the use of orthogonal planning are the Omride settlements of Samaria, Hazor, and Jezreel. However, given the limits of engineering capability, at Samaria only the acropolis demonstrates orthogonal planning, while the area below follows an oval shape. The only example of orthogonal planning in Judah is Lachish III, where orthogonal building units were planned within a peripheral contoured city.

Inside a settlement the quantitative relationship between public structures and private dwellings varied, revealing the administrative importance of the place. The form of the streets and open areas could also be revealing. Settlements that were carefully planned had streets of uniform width, without encroaching buildings, whereas minor settlements featured only irregular open areas to connect the various parts. In a well-planned settlement, open areas (such as at Lachish III and Megiddo VB-IVA) were useful for the encampment of military units (more often than not levies, as mercenaries had their own dwellings) in times of war, while in peacetime they housed markets.

A facsimile of the Siloam Inscription. The original is in the National Museum of Archaeology in Istanbul, Turkey. The inscription reads: ‘[The tunnel] was driven through. And this was the way in which it was cut through: while [there were] still […] axes, each man towards his fellow, and while there were still three cubits to be cut through [there was heard] the voice of a man calling to his fellows, for there was an overlap in the rock on the right [and on the left]. And when the tunnel was driven through, the quarrymen hewed [the rock], each man towards his fellow, axe against axe; and the water flowed from the spring towards the reservoir for 1,200 cubits.’ (Author’s collection)

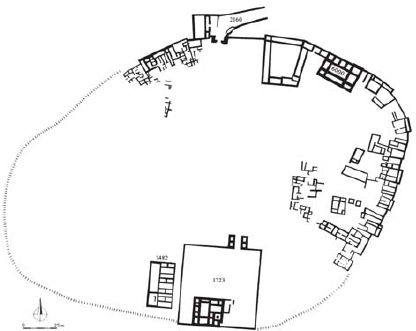

A plan of Megiddo, Stratum VA. Yadin identified this stratum with the city erected by King Solomon. The city included a six–chambered gate, and two palaces that stood in the southern part of the site, palaces 6000 and 1723. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

The major defensive components of Iron Age II fortifications include administrative buildings, city walls, city gates, palaces, storehouses and water systems. City walls were erected on huge glacis (slopes), which mostly dated to the Bronze Age and gave each tel its characteristic shape and contours. The glacis was created by piling compact earth on top of an existing mound or hill. These steep slopes were slanted at an average angle of 30 degrees and protected the city’s walls from the outside, hindering any attackers and preventing undermining attempts. They also protected the wall foundations from erosion. On the top of the glacis lay the city walls.

Iron Age II city walls are characterized by their stone foundations. The walls themselves were built using ashlar (dressed masonry) or brick, or alternating sections of ashlar and mud brick. Walls were sometimes built of undressed stones with ashlar used on the corners. The use of mud brick dates back to the Bronze Age, while the extensive use of ashlar is characteristic of the Iron Age, not just in Israel and Judah, but also in the surrounding Phoenician world. Ashlar usually came in long rectangular blocks, with drafted margins. These were laid in ‘header and stretcher’ courses, that is, placing some with their long sides parallel to the line of the wall and others with their short sides perpendicular to it.

Various types of walls were built. First, particularly in Iron Age I, the outer wall of the private dwellings contoured around a mound served as a defensive wall. This type was found mainly in smaller settlements. During the United Monarchy much use was made of the so-called casemate wall, which consisted of two parallels walls joined at determined intervals by perpendicular walls. Casemate walls could be freestanding, as at Megiddo VA, or could be integrated into city buildings, as at Beer-sheba II. Casemate walls could be used as soldiers’ dwellings, or to store food or weapons that could be used in case of siege. Sometimes the stone casemates served as a framework, which was filled with earth. From the Divided Monarchy onwards massive walls are more frequent. The earliest type is the inset and offset type, built with sections of around 6m long that alternately project and recede. The degree of projection was 0.5–0.6m. Megiddo IVA is the best example of this type. In Judah massive walls with square towers or bastions projecting outwards were common. The towers probably rose higher than the rest of the wall. Lachish III and Hazor VA are good examples. Simple massive walls were used as well. Such walls were probably topped with crenellations, as at Ramat Rahel near Jerusalem, which has a crenellation consisting of three decreasing steps. The Assyrian relief depicting the siege of Lachish shows wooden battlements on which shields were hung to strengthen the defence. In the early 1960s, Yadin suggested a chronological shift from casemate walls to inset and offset walls caused by the Assyrian adoption of the battering ram. However, it seems more likely that the choice of walls was dictated by the importance of the settlement in the military and administrative hierarchy, as well as by the economic resources available at the time.

|

THE SOLOMONIC GATE AT MEGIDDO |

The gate was an important military as well as civic element. The monumental six-chambered gate, mentioned in the First Book of Kings, measured 17.8 × 20m in size. Built using ashlar, it stood in the northern part of the site. The gate complex included a frontal gate laid perpendicular to the inner gate, which was connected by a wall to the inner gate. Similar six-chambered gates have been excavated at Megiddo VB, Gezer and Hazor.

During the Iron Age II period there is a clear development of the city gate. During the United Monarchy the so-called six-chambered gate was used, whereas the Omrides favoured the smaller four-chambered gate. In Judah, after Sennacherib’s destructive campaign, the use of two-chambered gates is attested.

Megiddo, Stratum IVB. Yadin identified this stratum with the city erected by King Achab of Israel. The settlement was surrounded by a solid inset and offset wall, and featured a four-chambered gate. It included Palace 338, two huge complexes of storage buildings, probably used as stables, grouped in the northern and in the southern part of the city, and a water system. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

The six-chambered gate, excavated at Megiddo VB, Gezer, Lachish III and Hazor, included outer projecting towers, a central passage, which was 4.2m in width, and three square guard chambers on each side of the central passage, and was built of ashlar. At Megiddo VA–IVB, as well as Lachish, the six-chambered gate is preceded by an outer front gate perpendicular to the inner gate, and is connected by a wall to the inner gate. This created a closed space between the two gates that was easily defendable.

The four-chambered gate (found at Tel Dan, Megiddo IVA and Beer-sheba II) consisted of a central passage, flanked by two square guard chambers on each side of the central passage. It seems that the reduction from six to four rooms was dictated by the increasingly military character of the city gate. In Biblical Israel, the city gates were the meeting place of the elders, and acted as courthouses (at Megiddo benches were found around the gate). At Megiddo IVB the four-chambered gate still utilized the outer gate, whereas at Dan it was preceded by a simple outer gate which faced the inner gate. The two-chambered gate consisted of a simple central passage, flanked by a square guard chamber on each side of the central passage. This type of gate has been excavated at Lachish II and Tell Beit Mirsim.

City walls and gates were the main component of the city defence, but there were other buildings. The king or city governor lived in a palace, similar to the Bit Hilani type of palace, which for the Israelites had an inner courtyard (probably a Canaanite retention), an outer courtyard often surrounded by a wall, and a small gate; it was often built as part of a greater structure. Palaces were generally rectangular, and were entered through a portico, formed by two freestanding pillars, with two more pillars attached to the walls. The pillars were topped by Proto-Aeolic capitals, subdivided into two types: Israelite (Megiddo and Hazor), and Judahite (Jerusalem and Ramat Rahel). Sometimes monumental steps preceded the entrance. A long rectangular-shaped reception room immediately followed the entrance. To the sides and the rear were smaller, square rooms, probably used to store goods or to house guards. A staircase led to an upper floor, which was probably used for dwelling. Sometimes there was a tower at the back of the building. Israelite palaces have been excavated at Megiddo (palaces 1723 and 6000, which probably date to the United Monarchy period, and Palace 338, which dates to the Omrides) and at Lachish III. Smaller palaces in the form of four-room houses were built in less important centres. At Hazor the citadel was rectangular and divided into elongated spaces; however, the central space was divided into two elongated units. The governor’s palace at Beer-sheba II was similarly shaped.

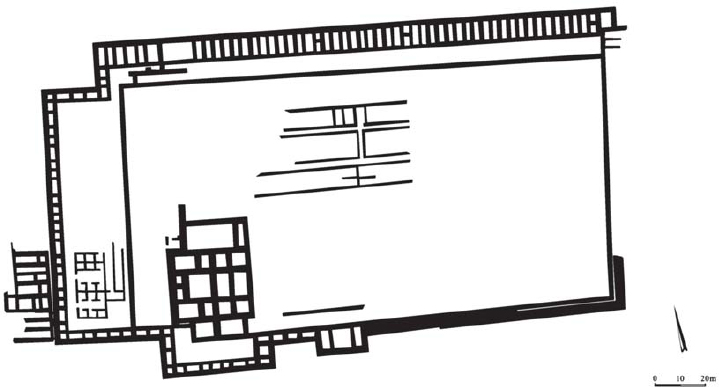

Omride Samaria. The royal acropolis consisted of a levelled rectangular enclosure, on a characteristic orthogonal plan. The rectangular plan, also seen at Hazor and Jezreel, was characteristic of Omride citadels. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

Administrative buildings have been excavated at Samaria and Hazor, consisting of an elongated courtyard flanked by a wing on each side, divided into various rooms. In the administrative buildings were stored the royal records, often written on papyri. Storage buildings found at Megiddo IVA, Hazor and Beer-sheba II are elongated rectangles in form, and are divided into three parallel aisles. The aisles are divided by two parallel sets of pillars. It seems that the central aisle was slightly higher than the two side aisles, as it was used as a passage. The two side aisles could be used to store goods, but those found at Megiddo IVA have been identified as stables for the war chariot horses.

Huge water systems are one of the main characteristics of Israelite fortifications. These held water that often came from a source located outside the city walls. The system often consisted of a vertical shaft, with broad steps leading down to a horizontal tunnel, which in turn led to the water source, often in a cave. The entrance to the cave from outside the citadel was of course blocked off. Water systems have been excavated at Megiddo, Hazor and Lachish; the latter, however, was not finished. The water system of Jerusalem will be discussed later.

Lachish, Strata V–III. The city fortifications are characterized by an outer and an inner defensive wall. The latter included a six-chambered gate. The city was dominated by a great palace fort, erected on a podium. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)