Megiddo

The main strata of the Israelite city are Megiddo IVB–VA. According to Yadin, Canaanite Megiddo, (Stratum VIA) was destroyed c.1000 BC. Soon afterwards, during the rule of David, it was rebuilt as an unwalled city with dwellings all along the outer perimeter of the mound (VB). According to Yadin, during the United Monarchy Megiddo was an important administrative centre and the seat of the governor of the Jezreel and Beth Shean valleys. Yadin identified Stratum VA with the period of King Solomon.

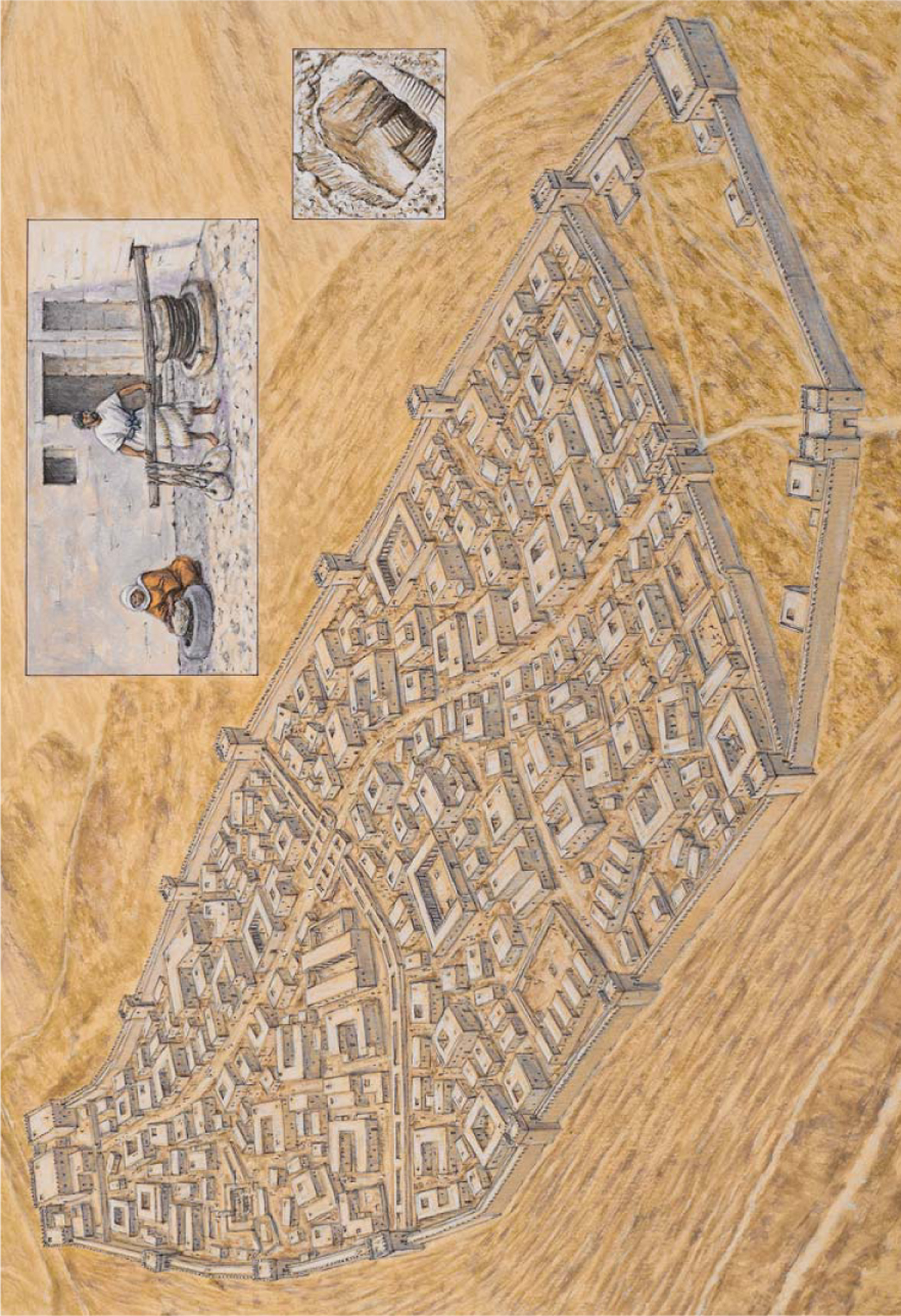

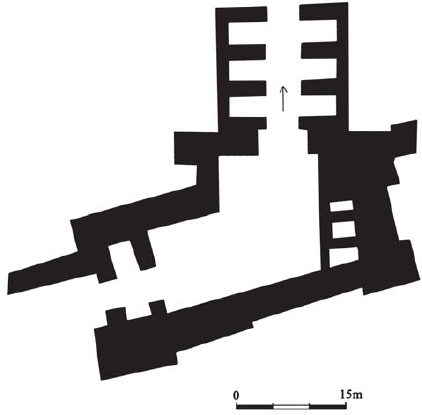

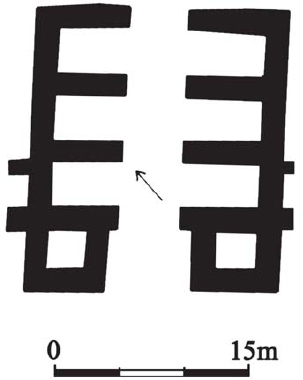

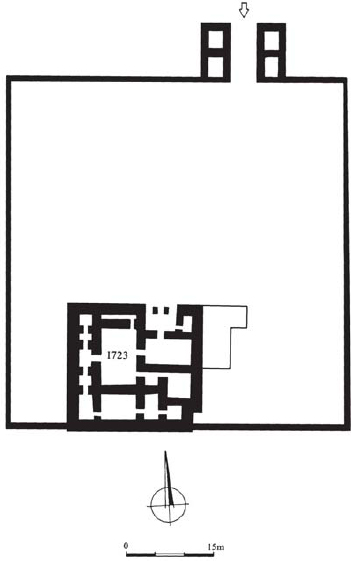

Solomonic Megiddo was surrounded by a casemate wall. A monumental six-chambered gate, mentioned in the First Book of Kings (9: 15–17) measuring 17.8 × 20m in size, built of ashlar, stood in the northern part of the oval-shaped mound. The gate complex included a frontal gate set laid perpendicular to the inner gate, and connected by a wall to the inner gate. The Solomonic city included two palaces that stood in the southern part of the mound, palaces 6000 and 1723. The northern one (6000) was rectangular, while the southern one (1723) had a more complicated plan.

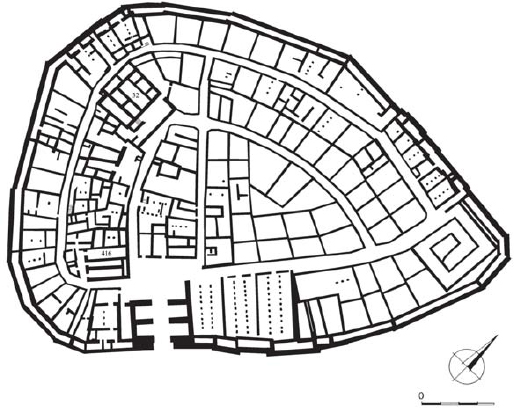

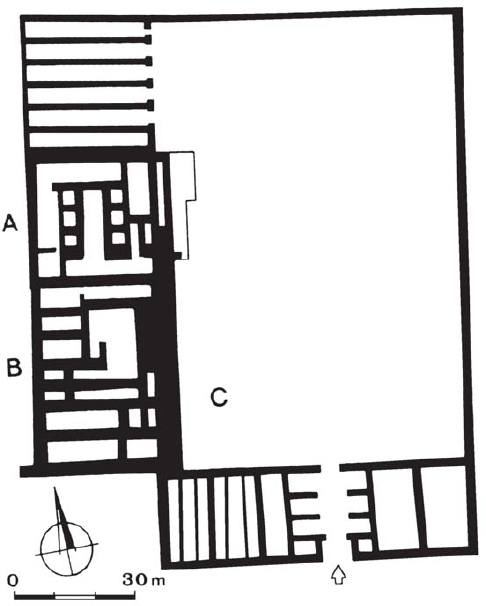

Beer-sheba, Stratum II. The main characteristic of the site is its radial plan. The city included a four-chambered gate, a casemate wall formed by the outer ring of private dwellings, a public building, the governor’s residency and a complex of three-pillared storage buildings. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

According to Yadin, the successive stratum IVA dates to the Omride Achab and was destroyed in 732 BC during the Assyrian conquest. At this time the settlement was surrounded by a solid, 3m-wide inset and offset wall. The six-chambered gate was retained for a while, before being replaced by a four-chambered one. Palace 338, built in the eastern part of the mound, served as the residence of high officials. The main characteristic of stratum IVA were the two huge complexes of pillared buildings, probably used as stables. The northern set stood east of the gate, and consisted of two complexes each composed of five units. According to various scholars, the northern buildings could hold 300 horses altogether. The southern complex, consisting of five more units, was built west of Palace 1723, now destroyed. This complex was preceded by a rectangular courtyard. The Megiddo water system consisted of a shaft over 30m deep, cut into the bedrock. It led down to a horizontal tunnel more than 60m long, which led to a natural spring on the edge of the tel.

Yadin’s stratigraphy has been criticized by Aharoni and Herzog. According to Aharoni, Stratum VB dates to the time of David, and includes only palaces 6000 and 1723. The successive stratum IVA included the inset and offset wall, which is the only wall that can be related to the six-chambered gate. Both this wall and the four-chambered gate must date to the reign of Solomon. The Solomonic city also included the two ‘stable’ complexes. Other archaeologists, such as Finkelstein, date both levels to the Omride dynasty.

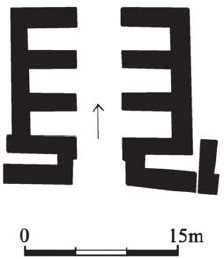

The Israelite city developed on top of the Bronze Age Canaanite acropolis. Five strata relate to the Israelite period, Strata IX–V. Solomonic Hazor, dated to Stratum XB, occupied only the western half of the upper mound, an area of approximately 8 acres (3 hectares). The Solomonic city was surrounded by a casemate wall. The entrance was through a six-chambered gate, situated on the eastern part of the citadel. The gate was similar to that of Megiddo, though built of undressed stone. The successive stratum, IXA–B, does not show any deviation from the Solomonic citadel. It seems that Hazor was destroyed during wars with the Arameans in the 9th century BC.

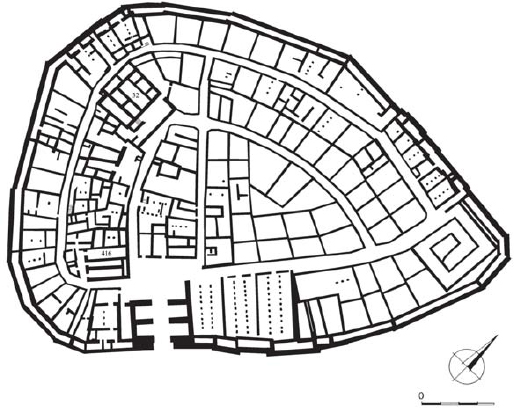

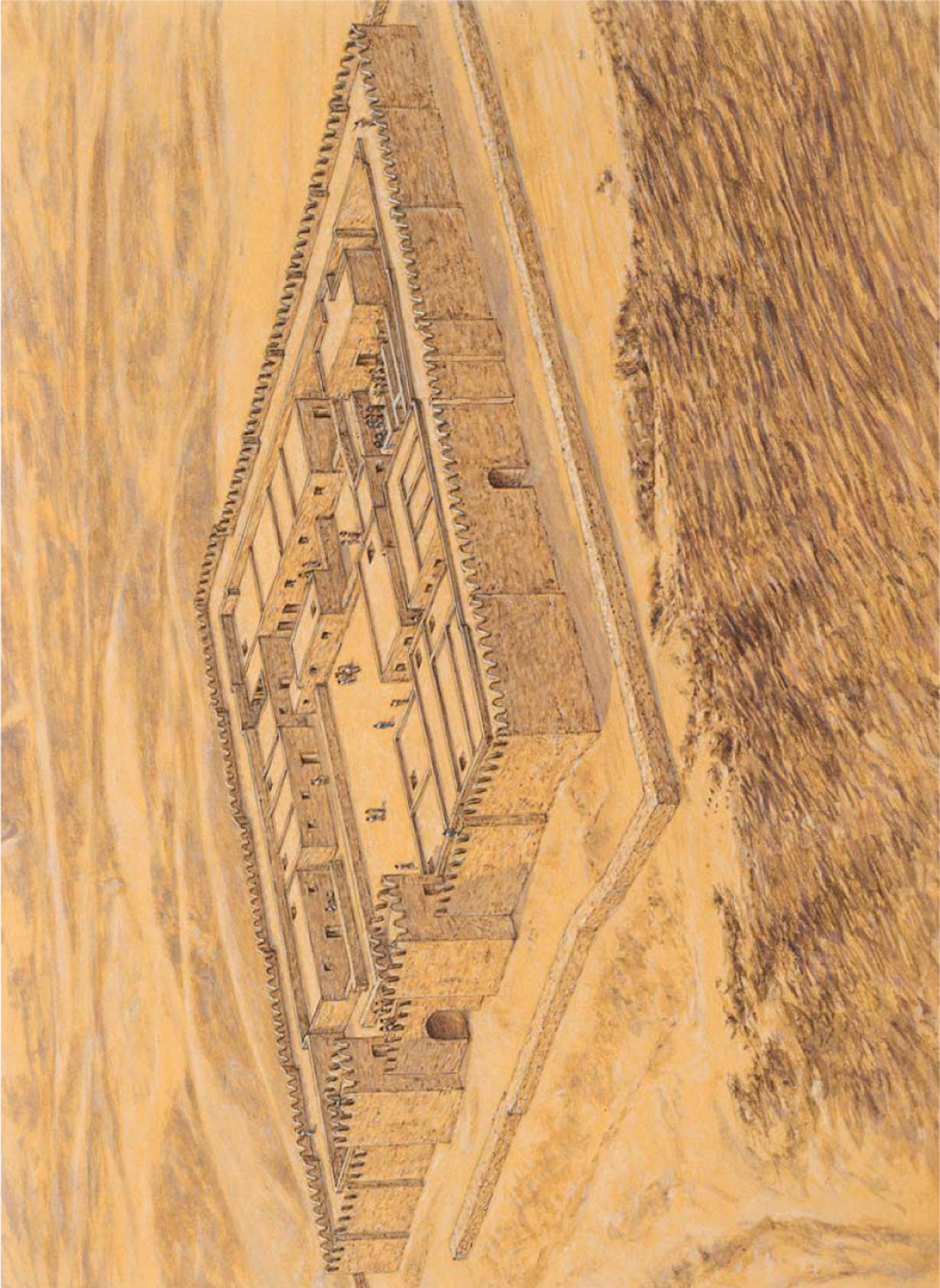

The successive Stratum VIII dates to the Omride dynasty, to the time of Achab. The city had doubled in area, now occupying the whole upper mound, and was surrounded by a solid wall. A small fortified palace (Area B) was located on the narrow western spur of the mound. It was separated by a wall from the rest of the city and it was entered by a gate decorated with ashlar pilasters, topped by Proto-Aeolic capitals. The citadel was rectangular in shape and divided into elongated spaces; its central space was divided into two elongated units. Two sets of administrative buildings, consisting of an elongated courtyard flanked by a wing divided into various rooms, stood on each side of the fortified palace. Omride Hazor had a storage building as well as a large granary. The water system consisted of a large vertical shaft cut into the solid bedrock below. Because of its 30m depth, support walls were erected. Broad steps led to the bottom, where a sloping tunnel, 25m long, led into a rock-cut chamber into which groundwater flowed. The successive strata of Israelite Hazor did not greatly change the Omride citadel. Stratum VI, dating to the reign of Jeroboam II, was probably destroyed by earthquake (see Amos 1: 1, and Zechariah 14: 5). Stratum VB is dated to the reign of Menachem. In the successive Stratum VA the fortifications were broadened on the eve of Tiglath Pileser III’s invasion in 732 BC (Second Book of Kings 15: 29).

|

THE CITADEL OF HAZOR IN THE OMRIDE PERIOD |

This plate depicts Stratum VIII, dated to the middle of the 8th century BC and the rule of Achab. The city had by now doubled in area, occupying the whole upper mound, and it was surrounded by a solid wall. The earlier Solomonic casemate wall and the six-chambered gate were by then no longer in use. A small fortified palace was located on the narrow western spur of the mound. The city included a storage house as well as a large granary. The water system consisted of a large vertical shaft cut into the solid bedrock below. A characteristic of Hazor was that the walls and gates were built using undressed stone, which was later covered by layers of plaster. The two inset illustrations show an olive press, and the entrance to the shaft of the water system.

The new capital of the Northern Kingdom was founded ex-novo (from scratch) by Omri, and named Shomron. The acropolis of the city was situated on a hill owned by a certain Shemer (First Book of Kings 16: 23–24). Ahab, his successor, completed the construction of the city, which thrived for 150 years, until the Assyrian conquest in 720 BC. The location of the settlement can be linked maybe to Omri’s foreign policy; it was situated north-west of Shechem, near an important road running towards the Sharon Plain on the coast, and on another leading northwards through the Jezreel Valley to Phoenicia. Moreover, the city was strategically situated on a steep hill, offering a good view of the surrounding countryside.

The excavations were concentrated on the top of the city, where the royal acropolis stood. In fact very little is known of the city itself, which covered an area of several dozen acres. The royal acropolis consisted of a huge, levelled rectangular enclosure, measuring 89 × 178m, which covered an area of 5 acres (2 hectares). The acropolis presents a characteristic orthogonal plan; the top of the hill had to be flattened before the huge royal compound could be built. The earthen fill packed behind the supporting wall was no less than 6m deep in some places. The casemate outer wall, which surrounded the acropolis, was probably designed to relieve the immense pressure of the fill, and the casemate chambers were probably filled with earth. The rectangular plan, common to Hazor and Jezreel as well, is characteristic of Omride citadels. The entrance gate was located on the east side, and was protected by a huge tower.

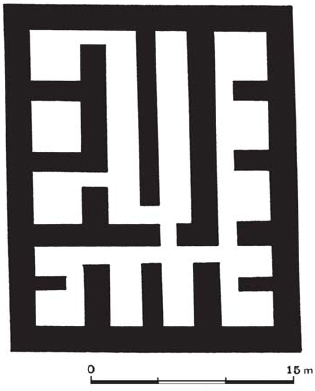

A plan of the six-chambered gate at Megiddo. The gate included outer projecting towers, a central passage and three square guard chambers on each side of the central passage. The gate complex included a frontal mono-chambered gate set perpendicular to the inner gate, and connected by a wall to the inner gate. (Dalit Weinblatt-Krausz)

The palace complex displays two main phases of planning and construction. In the first, probably dating to Omri, the main part of the acropolis was paved with a thick lime 15m floor and it was surrounded by a fine ashlar masonry wall, 1.6m thick, built using the header and stretcher technique. In the second phase, dating to Achab, the outer wall was replaced on the northern and western sides by a casemate wall. In the north the axis of 54 elongated casemates was perpendicular to the line of the wall. On the south and east sides were 52 smaller rooms. The casemate rooms provided storage space for royal treasures, an arsenal and food stocks.

The central palace, rising on the side of the artificial platform, covered an area of approximately half an acre (0.2 hectares). At the centre was a large rectangular courtyard, flanked by several wings. Only the southern one has been preserved. It included rectangular rooms surrounding a central inner courtyard. One of the palace’s rooms was filled with ivory, used to inlay palace furniture; the First Book of Kings (22: 39) alludes to the ivory house built by Achab.

Jerusalem

Prior to becoming the capital of the Davidic monarchy, Jerusalem was a small Canaanite city (Jebus). Its topography suggested a natural development. The Canaanite city of Jebus was situated on a ridge running north–south, surrounded by the Kidron Valley on the east, and the so-called Tyropoeon Valley on the west. On the north a small hill, Mount Moriah, connected by a ridge running east–west (the Ophel), defended the city. On the east lay two ridges, the northernmost being Mount Scopus, and the southernmost being the Mount of Olives. Thus, the settlement of Jebus lent itself to defence. On the eve of the Israelite conquest, the Jebusite city occupied a surface area of 10 acres (4 hectares), and had a population of 2,000 people. The earlier Israelite settlement bypassed Jebus, and thus at the time of Saul Jebus was still a Canaanite enclave in the territory of the tribe of Benjamin. It is interesting that King Saul erected his fortified residence, Givath Shaul, at Tell El-Full, only a few kilometres from the Jebusite city.

The Jebusite city was captured by David (Second Book of Samuel 5: 6–9, and First Book of Chronicles 11: 4–7), and he made it the administrative and religious centre of his kingdom. Although the city was situated in the territory of the tribe of Benjamin, the smallest and least powerful of the tribes, it was near the territory of Judah, the tribe from which David had come; thus it could be said that the capital of the kingdom was situated in an area acceptable to all the tribes, including the two northern tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh. Indeed one of the first acts of David was to transport the Ark of the Covenant to Mount Moriah, north of the city of David. It seems that in this period the city assumed the name of Jerusalem. King David continued to use the earlier Jebusite wall, but erected a palace to serve as the new royal residence and administrative centre of the kingdom on the old acropolis; this was probably located on the Millo, on the north–eastern extremity of the City of David. It was built using a filling of stone and soil, and reinforced by thin stone walls, creating an artificial tel. This was surrounded with a system of terraces to strengthen the tel. This palace may have been erected with the help of King David’s ally, the Phoenician King Hiram of Tyre (Second Book of Samuel 5: 11).

However, Israelite Jerusalem is mainly connected to King Solomon, the son of David by Bathsheba. Solomon’s building projects there, which were probably executed in the first years of his kingdom, are mentioned in the First Book of Kings (6: 1–7, 2, and 7: 13–7, 51) and in the Second Book of Chronicles (4). Solomon built a palace, and his famous temple on Mount Moriah, which came to be known as the Temple Mount. The Temple was a rectangular-shaped structure, divided into three parts: the Ulam, the Hechal and the Gvir. Two pillars in bronze stood in front of the Temple. Together with the Temple, Solomon erected a palace, described in Kings 7: 1–11. The palace included various halls, the ‘House of the Forest of Lebanon’, the ‘Hall of Pillars’, the ‘Hall of the Throne’, ‘his own House’, for dwelling, and ‘the other court’, and was probably inspired by contemporary Cypro-Phoenician architecture. It seems that Solomon reinforced the city fortifications; a casemate wall was uncovered by Kenyon in the area of the City of David that has been linked to similar Solomonic structures at Megiddo and Hazor. The Warren Shaft – the main well of the city – also dates to this period. This shaft was built on the hill of the City of David, to enable water to be drawn from the Gihon spring during sieges. Jerusalem expanded slightly during King Solomon’s reign, reaching an area of 32 acres (13 hectares), and had a population of 5,000.

The six-chambered gate at Megiddo. The gate was built using a mixture of ashlar and undressed stone. (Author’s photograph, courtesy of Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

After King Solomon’s death, and the end of the United Monarchy, Jerusalem assumed the role of a provincial city. The third period of growth started only with Uzziah’s reign in the 8th century BC. According to the Second Book of Chronicles (26: 9) he reinforced the walls of Jerusalem and built the towers. Jotham continued to fortify the city. However, the situation changed dramatically after the fall of Samaria to the Assyrians in 722 BC. Many Israelites, fleeing the Assyrians, settled in Jerusalem. By the time of Hezekiah, Jerusalem covered an area of 25 acres (10 hectares), and had a population of no fewer than 25,000 souls.

Hezekiah erected a new wall that encompassed the new quarters west of the City of David in preparation for a possible military confrontation with the Assyrians. This new wall began on the west side of the Temple Mount, and continued westwards all along the Transversal Valley, to the northern slopes of Mount Zion. From there it turned southwards all along the western slopes of Mount Zion down to the Valley of Hinnom in the south, then it turned eastwards, joining the City of David in its southern part. The northern section of this huge wall was excavated in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem. The section is 65m long, and is no less than 3.5m thick. Two towers were discovered on the line of the wall, probably pointing to the existence of a gate. Under the ‘broad wall’ were found remains of private dwellings.

A plan of the six-chambered gate at Hazor. The gate was similar to that at Megiddo, though built of undressed stone. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

The most ambitious defensive preparations comprised the erection of various structures, the task of which was to bring water to the besieged population. Hezekiah enlarged the city wall to include the Siloam Pool, and then constructed the horizontal Hezekiah Tunnel, which connected the Gihon Spring (outside the walls) to the Siloam Pool (Second Book of Kings 20:20 and Second Book of Chronicles 32:30), an event recorded in the Siloam Inscription in the Istanbul Museum of Archaeology. Hezekiah also erected a dam across the Beth Zetha Valley to catch the floodwaters there. In addition, the northernmost of the two Bethesda Pools was excavated; an opening was made in the dam to drain off water to a conduit. Hezekiah’s Jerusalem valiantly withstood the Assyrian Siege of 701 BC. Indeed, the fortifications built by Hezekiah would endure until the sieges of Nebuchadnezzar in 597 and 587 BC.

The six-chambered gate at Hazor. This photograph clearly shows the two parallel sets of three chambers. (Author’s photograph, courtesy of Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

Kuntillet Ajrud

This unique site along the ‘Gaza Road’, is located about 50km south of Kadesh Barnea. An isolated building was erected on the top of a steep hill, near a crossroad leading into the Sinai Desert and close to water wells. The building was rectangular in shape, measuring 15 × 25m, and consisted of a large central courtyard surrounded on three sides by long casemate rooms with projecting corner towers. The entrance was through a gate chamber which created a ‘bent axis’ approach into a broad room. In both rooms benches were constructed along the walls, and white plaster covered the walls, floors and benches. Among various finds were objects made of organic materials, such as basketry, ropes and textiles. The lack of Negbite handmade pottery here shows that there was no relationship with the local nomads. The pottery that was found indicates a date between the mid 9th century and mid 8th century BC. The combination of Israelite and Judahite elements may reflect a period when the Northern Kingdom’s sphere of influence extended to Judah, as during the reign of Queen Athaliah.

The mound on which Lachish stands (Tell el-Duweir) is located in an area in the Lower Shephelah, near the main road leading to the southern coastal plain, and occupies a surface area of 20 acres (8 hectares). During the United Monarchy, Lachish, Stratum V, was only partly rebuilt, and remained unfortified. The erection of the huge city and its fortifications, Stratum IV, can be dated to King Rehoboam (Second Book of Chronicles 11: 9). Stratum III, when the city reached its peak, was destroyed during Sennacherib’s siege and conquest in 701 BC. During the reign of Manasseh the city was rebuilt (Stratum II). The city was finally destroyed in 587 BC.

Lachish was the administrative and military headquarters of Judahite government in southern Shephelah. The city fortifications are characterized by an outer and an inner defensive wall. The outer wall was erected on the middle of the mount’s slope, while the inner wall was erected at the summit. The inner wall was 6m thick, and had a stone foundation topped by bricks. The city gate complex includes an access ramp along the slope of the mound, and an outer and inner gate. The outer gate was protected by a huge bastion erected on the slope of the wall. A small piazza inside the outer wall led to a six-chambered gate. This must be early in date, and was possibly erected not many years after Solomon. However, according to Ussishkin, who excavated the city, the city fortifications were mostly erected by either Asa or Jehoshaphat. The fortifications of Stratum II were less solid, and the gate complex was much weaker. The inner and outer gates were both of the two-chamber type.

The whole northern part of the city was allocated to a royal government. It was separated from the city by a huge, thick wall. Its main structure was a great palace fort, erected on a podium. The first phase of the building consisted of a square structure, which measured 32 × 32m; its date is unclear, being erected either in Stratum V, during the United Monarchy, or in the following Stratum IV. During the next phase, the building was enlarged to the south by 44m. During the last phase, the palace was enlarged to the east, resulting in the final structure of a huge building measuring 36 × 76m. It remains the largest Iron Age structure excavated in Israel. The podium elevated the building 6m above the surrounding land. The plan of the palace itself is unclear. East of the palace stood a spacious, paved courtyard surrounded by a defensive wall and entered via a six-chambered gate structure. Elongated rectangular buildings on the side of the courtyard served as storerooms, or perhaps stables.

The United Monarchy fortified enclosures

Rapid and widespread settlement occurred in the Central Negev Highlands during the United Monarchy. Various enclosures, excavated in the area, date from this period. The Central Negev Highlands are bordered on the east by the cliffs of Nahal Zin, on the south by the depression of Machtesh Rammon, on the west by the oasis of Kadesh Barnea and on the east by the Sinai Desert.

About 50 fortified enclosures, often referred to as fortresses, have been surveyed and excavated. Often these were erected near water sources or wadi beds. Most of the fortresses were situated on hills within sight of each other. The widespread distribution points to a general settlement in the region, and not control of any specific area. Most of these fortresses were 25–70m in diameter; their shape could be circular, oval, triangular or amorphic, following the contour of the hill. Usually they include a row of casemate walls with rooms and a large central courtyard, the latter accessed through a narrow entrance. The main examples are ‘En Kadesh, Atar Haro’e, Hurvath Haluqim, Hurvat Rahba, Hurvat Ketef Shifta and Ramat Matred.

A plan of the six-chambered gate at Gezer. (Dalit Weinblatt – Krausz)

Palace 1723 at Megiddo. This building was preceded by a rectangular courtyard that was entered through a four-chambered gate. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

Groups of dwellings have been excavated near these fortresses. The sites were only briefly inhabited. Two groups of pottery were found. The first consists of wheel-shaped pottery identical to that found in other sites dated to the period of the United Monarchy in Judah. The second consists of handmade pottery called Negbite ware, which was made by local nomads.

According to B. Rottemberg, D. Eitam and I. Finkelstein, these fortified enclosures were made by Amalecites, or Israelites of the Tribe of Simeon, and later destroyed by Saul. Finkelstein stresses the similarity between these structures and modern Bedouin pens. However, various scholars contest this earlier dating. If these settlements were erected by Amalecites, it is unclear why Israelite pottery was found in situ. Aharoni suggested a gradual Israelite penetration of the Negev Highlands. He therefore dates these fortresses to Iron Age I, the 11th century BC, contemporary to the Israelite settlement of Tel Masos. However, Glueck, Meshel and Cohen view these sites as the result of a royal initiative. As the Israelites established farms in the Negev Highlands, administrative centres were built to host royal officials and landowners. According to Meshel, these fortresses were established during the reign of Saul to protect against desert nomads, such as the Amalecites. Cohen dates these fortresses to the reign of Solomon. These settlements were destroyed as a result of a Shishaq military campaign in the region. In fact Shishaq’s list on the walls of the Temple at Karnak includes no fewer than 70 place-names from the Negev.

The Judahite defence of the Negev was concentrated in two main areas, the Northern Negev and the Central and Southern Negev. The area reached its main phase of development only in the 7th century BC. The main tasks of these fortresses were the control of the trade road descending towards the Dead Sea and Transjordan, to defend against the Edomite raids and to protect the local nomadic population. Various finds from the Northern Negev point to its role in international trade during this period. The prosperity of the region must have been related to Assyrian economic and political interests, which furthered trade connections between Edom, Judah and the coast through the Negev. This economic activity continued even after the fall of Assyria. The finds include pottery from Edom and Philistia, and Assyrian imported artefacts. Slowly the area passed from Judahite to Edomite control. The main Edomite site excavated in the region is Hurvat Qitmit.

|

BEER-SHEBA IN THE NORTHERN NEGEV |

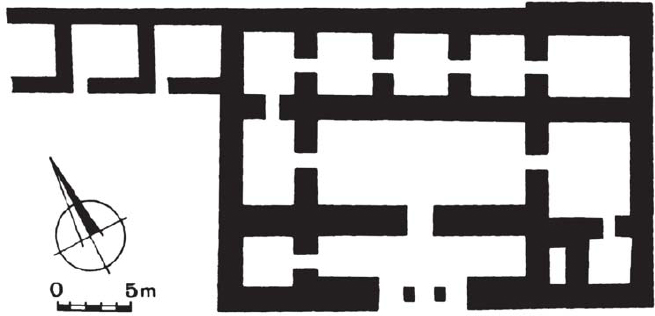

Tel Sheba in the Northern Negev has been identified with the Biblical Beer-sheba. The latter was the most important citadel in the area. The site covered an area of approximately 11,500m2. The city of Strata III–II was defended by a casemate wall, and it had a four-chambered gate. The main characteristic of the town is its radial plan. The governor’s palace was located near the city gate. A complex of three-pillared buildings, probably used to store food, was erected adjacent to the city gate. At the north-eastern corner of the site stood a water shaft.

Palace 6000 at Megiddo, similar to the Syrian Bit Hilani style of palace, was a rectangular structure. It was entered through a monumental ‘distylos in antis’ (i.e. with two columns in front), which was immediately followed by the reception hall in the centre of the building. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

The main fortresses in the Northern Negev, Beer-sheba and Arad, are dealt with below; other fortresses were at Hurvat Uza, Tel Ira, Aroer, Tel Masos and Tel Malhata. After the 10th century BC, the Central and Southern Negev areas remained unsettled until the end of the Iron Age. Only three Iron Age II settlements are known south of Beer-sheba: Kadesh Barnea, Kuntillet Ajrud and Tell el-Kheleifeh. All these settlements indicate a major Judahite effort to control the approach to the Red Sea along the Gaza Road during the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Trade relations with Arabia through the Red Sea continued as part of international trade between Edom, Judah, Israel and the Phoenicians, under Assyrian guidance. In the 7th century Edom took possession of the sites in the Northern Negev.

During the 9th and 8th centuries BC the small town of Tel Beer-sheba in the Northern Negev was the main Judahite centre in the region. It was well planned and it underwent several stages of development. The entire area covered approximately 11,500m2. The initial Stratum IV, dated to the 10th–9th century BC, was a fortified town surrounded by a solid wall and a massive earth rampart, entered through a gate. In Stratum III–II, the solid wall was replaced by a casemate wall, and the gate was rebuilt as a four-chambered gate, located on the south-east side of the town. The main characteristic of the town was its radial plan. Three main streets shape the city. The first consists of a circular, outer, peripheral street parallel to the city wall, that was separated from it by a row of buildings. The second consists of an inner peripheral street, which was parallel to the outer one. In addition, the settlement is divided in the middle by a street leading from the city gate. The outer street was separated from the casemate wall by a line of houses integrated into the wall itself. The casemate wall consisted of the outer wall of the four-roomed houses.

The governor’s palace identified by Aharoni, the excavator, was located near the city gate. It was built on undressed stone foundations, using ashlar and mud bricks. It was more or less a two-storey squared building, which measured 10 × 18m. Small rooms on the western and southern sides served as living quarters and service rooms. It seems that the ceremonial area was located in the long halls on the eastern side of the second storey. A complex of three-pillared buildings was erected adjacent to the city gate, and the façade of each faced the street. It seems that these buildings were used to store food. These storage buildings indicate that town was the main administrative centre in the Northern Negev. At the north-eastern corner of the mound stood a shaft, with a flight of stairs built into the supporting wall; the shaft has not been excavated. Tel Beer-sheba was destroyed towards the end of the 8th century or in the early 7th century BC, during or after Hezekiah’s time.

During the Iron Age I period a small village already stood on the top of the tel at Arad (Stratum XII) in the Northern Negev. This was replaced by a royal fortress around the 10th century BC. The fortress served as an important administrative and military stronghold of the Kingdom of Judah in the region, guarding the road from the Judaean Hills to the Aravah, and to Moab and Edom. The fortress developed until the end of the Iron Age (Strata XI–VI). The earliest fortress (Stratum XI) was a square structure, around 50 × 50m in size, located on a high hill, which dominated the surrounding area. The fortress was surrounded by a casemate wall. This phase has been dated to Solomon’s reign, through a later date, the 9th century BC, can be accepted. The next stratum, Stratum X, is dated to Uzziah’s reign. The fortress was now provided with solid stone walls of inset and offset pattern. An entrance gate flanked by two towers stood in the middle of the eastern wall. A central courtyard was flanked by storage rooms, dwelling rooms and a temple located in its north-western corner. The water supply came from a deep, stone-lined well in the valley at the foot of the hill, from where it was brought by donkeys to a canal that passed through the outside wall of the fortress and into the rock-cut cisterns. According to Aharoni, the fortress continued to develop in Strata IX–VIII. The severe destruction exhibited in Stratum VIII is attributed to the Edomites, who in the wake of Sennacherib’s campaign in 701 BC, which drained the resources of the Kingdom of Judah, invaded the area and burned down the fortress. The fortress of Strata VII–VI, which followed the same layout, is dated to the 7th century BC. At the end of the 7th century BC the fortress was rebuilt, with an outer casemate wall (Stratum VI). The date suggested by Aharoni is not accepted by every scholar. According to Yadin and Dunayevsky, the fortress with inset and offset walls continued in use until the end of the Israelite period, and the successive fortress with casemate walls must be dated to the Hellenistic period.

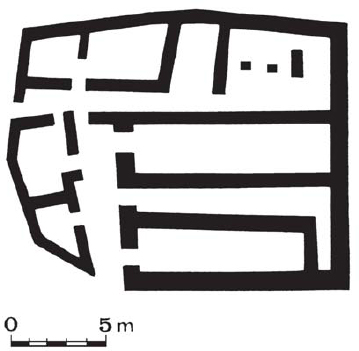

A plan of the citadel, Area A, at Hazor. The citadel, similar to the four-room house, was rectangular and divided into elongated spaces. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

The palace fort at Lachish, Stratum III, which was erected on a podium. This is the largest Iron Age structure excavated in Israel to date. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

Tel el-Kheleifeh

This site, not far from Eilath, was located at the ends of routes leading to the Red Sea. Excavated in the 1940s by Glueck, it has been identified with the Biblical Etzion Geber. According to the First Book of Kings (9: 26-28; 10: 1–13), it was established by Solomon as a base for trade in the Red Sea area. It seems that the site was established to further naval and mercantile activity by the United Monarchy, and later on by the Kingdom of Judah, in the Red Sea. The first fortress (Period I) consists of an open courtyard, measuring 45 × 45m, surrounded by a casemate wall. Inside the courtyard stood a single building planned as a four-room house. Later (Period II), the enclosure was enlarged to 60 × 60m. It was entered through a four-chambered gate and it was defended by a solid outer wall with inset and offset sections. The Period III fortification was similar in its layout to Arad, although smaller. During Period III, various structures were built inside the fortress courtyard. This well-planned fort had a military and administrative nature. It is possible that the Judahite stronghold of Etzion Geber in the 7th century BC passed into Edomite hands. Another possibility is that the fortress was an Edomite stronghold never related to the Israelites, but the presence of Judahite and Negbite pottery, which attests to the presence of local nomads, suggests this to be incorrect.

Kadesh Barnea was the most important oasis on the border between the Sinai and the Negev. During the 10th century BC an elliptical casemate enclosure was built on the mound of the oasis. It was the westernmost of a cluster of some 50 fortresses of the 10th century BC in the Central Negev highlands. Like all other fortresses in the group this site was destroyed towards the end of the 10th century BC during Shishaq’s campaign. However, although all the other sites were abandoned after their destruction, Kadesh Barnea continued to be an important Judahite stronghold in the following centuries, though perhaps after a gap of 100 years. The new fortress became the main Judahite base along the Gaza Road. This stronghold was also essential in controlling the nomadic population of the Negev and eastern Sinai.

|

THE FORTRESS OF ARAD |

Arad was a small fort located in the south-eastern Negev. The fortress was located on a high hill, which dominated the whole surrounding area. Stratum X is dated to the reign of Uzziah. The fortress was protected by a stone wall comprising inset and offset sections. An entrance gate flanked by two towers stood in the middle of the eastern wall. The central courtyard was flanked by storage rooms, dwellings, and a temple located in its north-western corner.

The fortress of Kadesh Barnea was a rectangular structure measuring 40 × 60m, enclosed by a 4m-wide solid wall with eight rectangular towers. Four of the towers stood on the corners, while the other four stood in the middle of each encircling wall. The wall was surrounded by an impressive earth rampart supported by an outer retaining wall. The gate has not been found. Perhaps entry was gained by way of a ramp on top of the earth rampart. A built-up water reservoir inside the citadel was filled from a canal bringing water from the oasis spring. This fortress was erected probably in the early 8th century BC during Uzziah’s reign (Second Book of Chronicles 26: 10). It was destroyed in the early 7th century BC, either by Nomads or by Edomites in the years after Sennacherib’s invasion and Manasseh’s reign. The fortress was rebuilt in the same shape, but this time the solid wall was exchanged for a casemate wall, which was the same width as the original. The fortress was destroyed in 587 BC.

The presence of so-called Negbite handmade pottery, side by side with Judahite wheel-made pottery, indicates the presence of a semi-nomadic local population, who may have lived together with the garrison, and probably benefited from royal resources.

The other main areas in which fortifications were erected in the Kingdom of Judah were the Judaean Desert, the Judaean Hills and Shephelah. In the Judaean Desert the main fortification excavated is located at Vered Jericho, not far from Jericho. This unique type of fortress guarded the road from Jericho to the Dead Sea. The fortress consists of a rectangular building, the entrance of which is defended by two flanking towers. Inside, the rectangular courtyard leads to two parallel and attached ‘four-room house’ units. The regular planning and defensive character indicate that the function of the building was official.

Several fortress and towers have been discovered in the Judaean Hills and Shephelah. The fortresses were square or rectangular in shape and had a large central courtyard surrounded by casemate walls with rooms on the outer wall. The two main fortifications discovered are located at Khirbet Abu et-Twein and Hurvat Eres. The former is located on the western slopes of the Hebron Hills. It stands on a high hill, with an excellent view of the Shephelah and the Valley of Elah. The building measures 30 × 30m in size. It had a chamber gate and a central courtyard surrounded by a double row of rooms. These two rows were separated by rows of monolithic pillars to which partition walls were attached. Khirbet Abu et-Twein formed part of a network of strongholds in the hilly and probably forested region which separated the Hebron Mountain ridge from the inner Shephelah. The fortress of Hurvat Eres was located on a high ridge west of Jerusalem offering a view of the coastal plain as well of the Jerusalem area. The location of the Judaean stronghold suggests that one of the main functions was to ease communications by fire signals between different parts of the Kingdom of Judah. The use of these communications is known from Jeremiah (6: 1) and the Lachish letters.

A plan of the governor’s palace at Beer-sheba. This square, two-storey-high building was located near the city gate. The ceremonial area was located in the long hall on the eastern side of the second storey. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

Moreover, around Jerusalem there were also freestanding, elevated, isolated, solid towers, usually built on podiums. Two of these are known. One is situated on a high ridge north of the city in the modern neighbourhood of French Hill, and the other on a ridge south of the city in the quarter of Giloh.