Most of the data that we have on the Israelite army comes from the Bible, and refers mainly to the army of the United Monarchy. Thus, according to Yadin, the Israelite army was made up of two separate formations: the regular army and the militia. The regular army consisted of two separate bodies, the Israelites and foreign mercenaries. The Israelite standing army probably originated in the people who gathered around David in the cave at Adullam, when the latter was fleeing from the jealousy of Saul. They consisted of around 400 men (First Book of Samuel 22: 1–2). Later, the number rose to approximately 600 men. Once David became king of all Israel, this group, often referred to as ‘David’s heroes’, formed the nucleus of the regular army (First Book of Samuel 30). Together with the king and the army commander, Joab Ben Serujah, a small part of this group known as ‘the Thirty’ were organized into a supreme army council. This body decided on promotions and appointments, framed army regulations and selected the permanent commanders of the militia army. David’s mercenary force consisted of the Cherethites, Pelethites, and Gathites (Second Book of Samuel 15: 17–21). The organization of the militia during the United Monarchy is described in the First Book of Chronicles (27: 1–15). According to Yadin, the text in Chronicles clearly indicates that by then the army was no longer organized on the basis of tribal levies, but rather its organization depended on a strong central administration. The organic division into 12 formations shows that the militia was organized in advance of any conflict, with permanent units of equal size. Moreover, the same quota was imposed on every region. The militia was called up according to the units and not according to individuals. It is probable that in times of emergency all units would be engaged. At the head of each of the 12 formations stood a leading commander, or ‘Commander of the Host’. Each formation consisted of 24,000 warriors, and was itself subdivided into units of thousands, each of which were divided into smaller units of hundreds. Last but not least, there was a system of rotation, with each formation serving for a month a year.

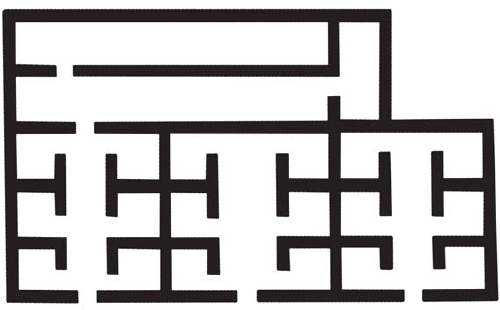

A plan of the administrative buildings west of the palace of Samaria. These three buildings featured an elongated central courtyard flanked on each side by wings that were divided on each side into three rooms. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

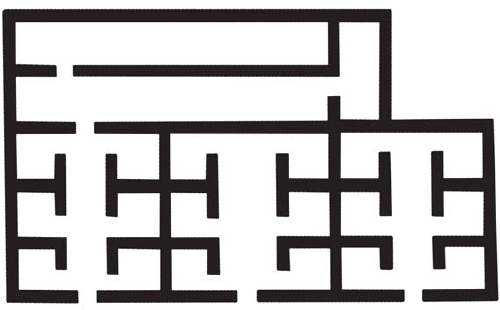

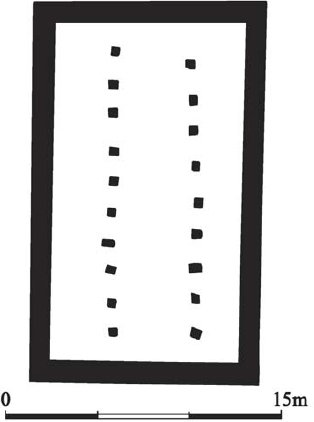

A plan of Building 71a, Area A at Hazor. This building takes the form of an elongated rectangle, divided into three parallel aisles delineated by two parallel sets of pillars. The central aisle was used as a passage, while the two side aisles were used to store goods. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

It is probable that the kingdoms of Israel and Judah retained the same structure for their respective armies. The only data that we have on the army of the Kingdom of Israel in its full strength, which comes from Assyrian documents, is that concerning the battle of Kurkar, when Achab fielded 500 chariots and 10,000 infantrymen. The sole information on the army of Judah comes from the Second Book of Chronicles and relates to the reigns of Jehoshaphat and Uzziah. The first passage (17: 12–19) relates to the reign of Jehoshaphat. The tribe of Judah was divided into three military districts, while the tribe of Benjamin was divided into two of them, depending on the royal administration. The second passage (26: 11–13) relates to the status of the army during Uzziah’s reign. The Judahite army now demonstrated the strong influence of the royal administration. Two officials, Jehiel, a scribe who kept the accounts, and the officer Ma’aseiah, were responsible for its organization. The various weapons, listed as ‘shields, and spears, and helmets, and body armour, and bows, and stones for slinging’, were kept in royal storehouses distributed around the fortresses of the kingdom. The field army was commanded by ‘Hananiah, one of the king’s commanders’. The Judahite army in this period was organized into units. The nucleus of the army consisted of 2,600 men, and when expanded the army numbered no fewer than 307,500 men. The latter number is probably grossly inflated, but it shows that the system of a small regular army working alongside a militia called up in times of emergency was maintained. Moreover, in the last years of the kingdom, probably from the reign of Josiah onwards, if not before, Greek mercenaries from Ionia served the kingdom as well.

The armies of the United Monarchy, as well as those of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, were made up of chariots, cavalry and infantry. According to the Bible (First Book of Kings 10: 26 and Second Book of Chronicles 9: 25), King Solomon possessed a strong chariot force. Yadin calculates the number of chariots as being between 500 and 1,400, stressing that the first number is probably closer to the truth. However, Achab at Kurkar had no fewer than 500 chariots. After the conquest of Samaria, Sargon organized a separate unit in the Assyrian army that numbered 50 chariots, the remains of the chariot unit of the Kingdom of Israel. It seems that the Kingdom of Judah possessed a much smaller chariot force than the Kingdom of Israel. The cavalry were divided into heavy cavalry armed with spears, and light cavalry armed with bows. The infantry were probably divided into three broad units: spearmen, archers and sling men. Spearmen, the heavy infantry, made up the bulk of the army; each was protected by a helmet, a cuirass, and a shield, and was armed with a sword and a spear. Archers and sling men were used as light infantry.

The remains of Building 71a, Area A at Hazor. (Author’s photograph, courtesy of Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

Although the army of the northern Kingdom of Israel, in which the chariots played such an important part, had an offensive character, the fortifications were still very important. In the Omride period, although Megiddo was rebuilt with complexes of stables for the chariots, the other fortifications of Dan, Hazor, Jezreel and the royal acropolis of Samaria stood as the main defensive strongholds of the kingdom. In contrast to the Kingdom of Israel, the army of Judah was much more closely linked to the kingdom’s fortifications. Here the static defence was based on a chain of previously discussed regional fortresses. The Bible stresses the importance of the various fortifications erected by Judah’s rulers. According to the Second Book of Chronicles (11: 5–12), Rehoboam fortified the cities of Beth-Lehem, Etam, Tekoa, Beth-Zur, Socoh, Adullam, Gath, Mareshah, Ziph, Adoraim, Lachish, Azekah, Zorah, Aijalon and Hebron. Jehoshaphat (17: 1, 12) fortified the cities in the tribal area of Ephraim, taken from the Kingdom of Israel by his father Asa. He also built castles and store-cities in Judah, including in Jerusalem. King Uzziah (26: 9–10) fortified Jerusalem, and erected various ‘tower’ fortifications in the Shephelah and in the Negev.

A manger set between two pillars, in the Northern Stables complex at Megiddo. (Author’s photograph, courtesy of Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

A pillared building in the Southern Stables complex at Megiddo. (Author’s photograph, courtesy of Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

The silos at Megiddo. (Author’s photograph, courtesy of Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

It is important to understand that the various fortifications erected in Israel and Judah did not have a solely military purpose. Most of the fortifications were primarily important as administrative centres. Thus, the royal official (‘Sar haIr’) who resided in and commanded the fortification was in fact a civilian. His main task in peacetime was to levy taxes from the area around the fortress, the administration of which he was responsible for. These taxes were often grain (wheat and barley), oil and wine. Part of the products collected was not sent to the capital, but was stored in the city storage houses in case of emergency. Although the Sar haIr had under his command the units of the standing army, which garrisoned the place, these had their own officers. It seems that most of the population, with the exception of those in the big cities such as Samaria in Israel and Jerusalem in Judah, did not live inside the city walls, but dwelt outside in houses scattered all around the countryside. However, the various officials, who assisted the Sar haIr – such as the scribes who kept the archives or the people responsible for managing the store houses, or various artisans – certainly did live inside the city.

Everything changed during times of war. First of all, the Sar haIr had to call on the militia. The various local levies were organized into a military force. The militia could reinforce the local regular garrison, or they could be sent elsewhere to defend an area or a place that was under more immediate threat from the enemy. In Judah, fire signals were used to announce that the enemy was approaching, giving time to prepare the city or the fort for a siege. Many logistical preparations had to be made. The local population, living in the surrounding area, naturally came into the site to escape the enemy army. The store houses had to be brought to maximum capacity, as the Sar haIr had to feed not just his officials, the army, the standing forces and the militia, but the whole incoming population as well. Space available was limited, and the resulting congestion could result in poor health and epidemics. The problem of feeding the civilians weighed heavily on the Sar haIr, and if there was insufficient food and water then famine would certainly follow. Next, the city fortifications were strengthened. Wooden battlements were erected on top of the walls and towers, and shields were hung from these to afford the maximum protection. The water system was also reinforced. The fortification was now ready to be tested by siege.

The ostraca (shards of stone or pottery bearing inscriptions) from Arad and from Lachish help us to understand how a city or a fort functioned in peacetime and how it prepared for siege. Those from Arad were found in various strata. A letter, dated to Hezekiah’s reign, was sent to the military commander of the fortress, whose name was Malkiyahu, and mentions conflict with Edom. However, most of the ostraca belong to the archives of a certain Elyashib, who commanded the fortress in a later period. These ostraca comprise the correspondence between Elyashib and other commanders in the upper military hierarchy. Seven of these letters were sent from Jerusalem. They include a fragmentary one from one of the last kings of Judah, perhaps Jehoahaz, who announces his enthronement, and discusses matters of international policy, mentioning the ruler of Egypt. Another ostracon orders the dispatching of troops from a place called Qinah to Ramoth Negev, which may be the fortress of Hurvath Uza, as an emergency measure to withstand the Edomite threat. However, most of the correspondence deals with logistical and not with strategic problems. Arad appears on the ostraca as a receiver and distributor of food supplies. Flour, oil and wine were sent from towns in the southern Hebron Hills, perhaps as royal taxes, and in turn were allocated by Arad to other forts and troops located in the Negev. Several other ostraca are letters of introduction to the commander of Arad from officials elsewhere in Judah, requesting that food supplies be assigned to a certain messenger. Other letters include instructions to send supplies to the Kittim, who were probably Greek mercenaries, serving in the Judahite army. The name probably originated in the city of Kition, in Cyprus. The discovery of Cypriot and Eastern Greek pottery in the Northern Negev enhances this possibility.

A cross section of the Megiddo water system. The system consisted of a vertical shaft, with broad steps leading down to its bottom. From there a horizontal tunnel led to the water source, which lay outside the city walls. (Dalit Weinblatt–Krausz)

The ostraca from Lachish are dated to Stratum II, slightly before the Babylonian destruction of the city during the last days of Judah. They consist of correspondence found in the burned debris of the city gate, which were written by a certain Hoshayahu to his commander Yaush. According to N.H. Tur-Sinai, Hoshayahu was the commander of a small fortress outside Lachish, while Yaush was the commander of Lachish. However, according to Yadin, these ostraca were drafts of correspondence sent from Lachish to Jerusalem. Accordingly, Hoshayahu would be the commander of Lachish, and Yaush a high official in the capital. One of the letters has a dramatic end: ‘And may my lord know that we are watching for the beacons of Lachish, according to all the signs which my lord has given, for we cannot see [the signals] of Azekah.’

Until the advent of the Assyrians, the main device used during siege warfare was the scaling ladder. The early Israelite fortifications, designed to withstand sieges by the neighboring Arameans, Moabites, Ammonites and Edomites, thus relied on casemate walls for their defence. These provided for the concentration of troops and storage, enough to defend the city. The besieged knew that time was on their side. Thus, if they had sufficient provisions to face a long siege, by harvest time the enemy army would be obliged to abandon the siege and return to their fields.

|

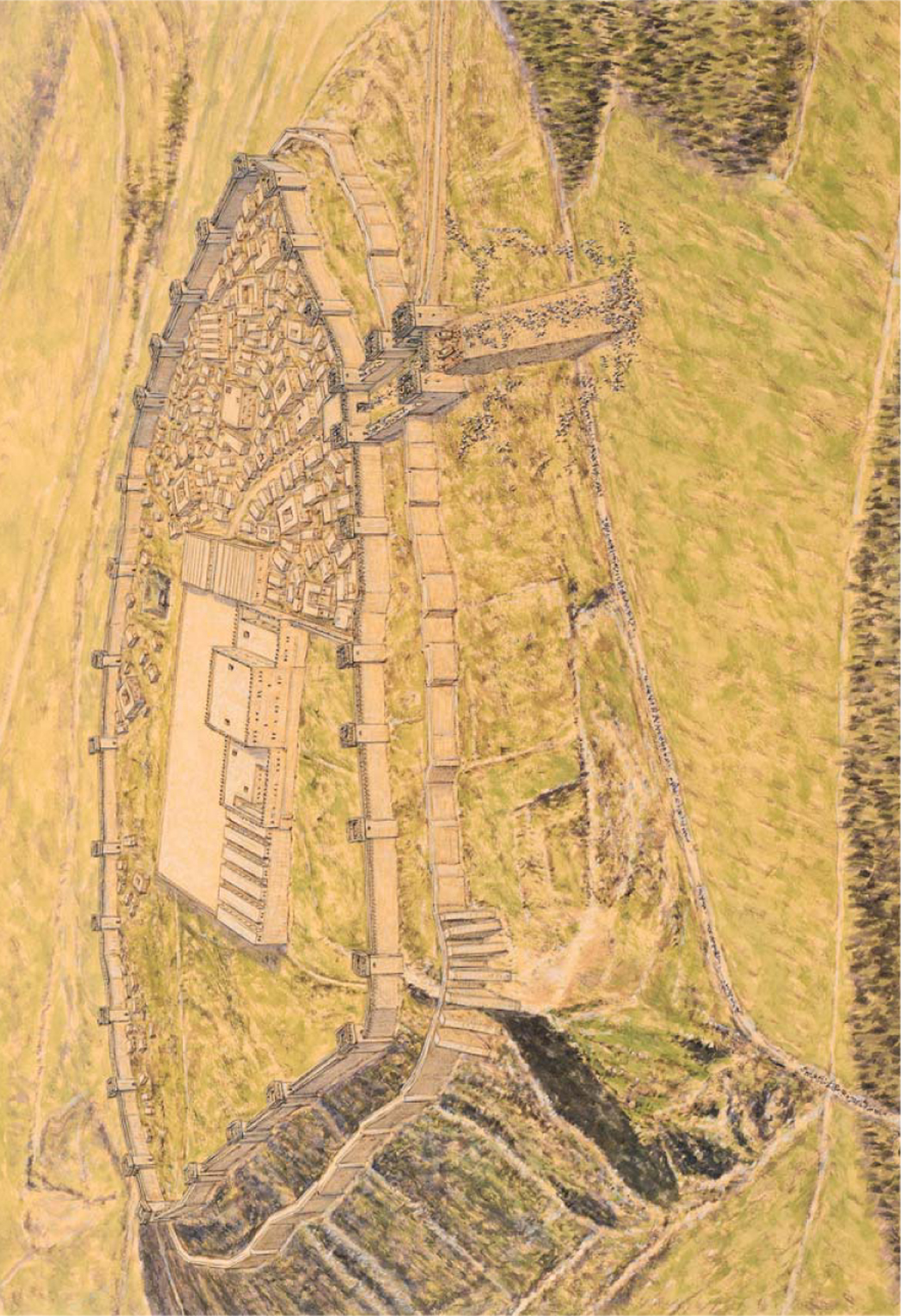

LACHISH: PREPARING FOR THE ASSYRIAN SIEGE |

After Jerusalem, Lachish was the most important city in the Kingdom of Judah. This illustration shows Stratum III, on the eve of the Assyrian siege, after the defenders had erected the battlements and emplaced their shields as a means of further defence. The city occupied an area of 20 acres (8 hectares). The city fortifications had an outer and an inner defensive wall. The city gate complex includes an access ramp alongside the slope of the mound, and an outer and inner six–chambered gate. The whole northern part of the city was separated off by a huge wall. The main structure comprised a palace fort, erected on a podium, in which resided the royal governor.

However, with the Assyrians siege warfare changed completely. The Assyrians were not only much more methodical in organizing sieges, but they also had new siege weapons, such as the battering ram. The defenders in Israel and Judah thus reacted by building stronger walls featuring inset and offset sections and fortified with towers. Once they had surrounded the city or fortification, the Assyrians erected a camp. Their army would then search for a weak spot in the walls, more often than not near the city gate. There they would construct an earth rampart, the purpose of which was to bring battering rams close to the city wall. This siege machine was rectangular in shape, and mounted on four wheels, and was topped by a wooden frame covered with animal skins. The front of the battering ram was topped with a tower, from where archers could fire incendiary arrows. The skins were kept wet so that the defenders could not set fire to the engine. The ram had a metal point on the end, and was used to batter a hole in the wall – which did not take long, given that the walls were more often than not made of mud-brick. Although the Assyrian army preferred to take the city by storm rather than wait for its surrender, psychological warfare was used, to reduce the costs of time and human life for the attackers. Any captured enemy troops were executed, having previously been subjected to various forms of torture. The watching city population would hopefully be terrorized into submission. With the exception of Jerusalem, which later fell to the Babylonians using the same siege methods as the Assyrians, the cities of Israel and Judah fell one after the other to the Assyrian besiegers.

The shaft of the Megiddo water system. (Author’s photograph, courtesy of Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

The tunnel in the Megiddo Water System. (Author’s photograph, courtesy of Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

After the city had been stormed, the Assyrians publicly executed the city officials and the military commanders who had refused to surrender. Then the Assyrians collected the remnants of the population to deport them to a far-off place. Often another population was settled in the ruined city instead. The Babylonians followed similar methods, but they preferred to deport only the ruling class. The Book of Lamentations describes in detail the fate of Jerusalem after the Babylonian conquest, and the terrible effects of the famine inside the city, as well as the fury of the enemy:

The tongue of the sucking child cleaves to the roof of his mouth for thirst; the young children ask for bread, and none break it unto them… They that did feed on dainties are desolate in the streets; they that were brought up in scarlet embrace dunghills… Her princes were purer than snow, they were whiter than milk, they were ruddier in body than rubies, their polishing was as of sapphire… now their visage is blacker than coal; they are not known in the streets; their skin is shrivelled upon their bones; it is withered, it is become like a stick… They that are slain with the sword are better than they that are slain with hunger; for these pine away, stricken through, for want of the fruits of the field… (Book of Lamentations 4: 4–10)