I SPENT A LITTLE OVER A YEAR IN JERSEY, THE LARGEST OF THE Channel Islands. This would be followed by two and a half years in London. I would be caught between East and West, and would have to make up my mind about where I belonged. The link with Britain was tenuous, after all; based on heredity rather than upbringing.

I had come to England with a dream of sorts, and I was to return to India with another kind of dream; but in between there were to be four years of dreary office work, dank and cheerless bed-sitting rooms, shabby lodging houses, cheap snack bars, hospital wards, and the struggle to write my first book and find a publisher for it. I discovered that the world could be a lonely place for someone like me. And I found that becoming a writer wasn’t just a matter of putting pen to paper—although that was certainly the first step!

Jersey was a beautiful island—wide bays, pretty inlets, a busy little port, a quaint capital (St Helier), and farms famous for tomatoes and Jersey cows. But I knew no one outside my aunt’s family, and my relatives showed no great interest in my literary ambitions.

Within a week of my arrival I was down with jaundice again. I must have picked it up in that seedy little hotel in Bombay, and the virus had been lurking in my system throughout that long sea voyage. Certainly no one in Jersey suffered from jaundice or any tropical disease. But with the right diet and rest I recovered quickly, and immediately set about looking for a job. I did not want to be a burden on my aunt any longer than was absolutely necessary.

I did not waste time with job applications or employment agencies. I simply set out down the high street of St Helier, knocked on doors, waited outside offices, walked up to anyone who appeared to be in charge and enquired politely: ‘Excuse me, sir, I’m looking for a job. Do you have a vacancy?’ Usually there was no vacancy, but people were surprised at my direct approach and occasionally someone would ask me what I could do. ‘I can type,’ I’d say. ‘I know a little shorthand. I can attend to correspondence. I can make out a bill.’ And then in desperation: ‘I can make tea.’

The office manager of a large grocery chain, Les Riches, looked me up and down and asked me if could do any accounting. ‘Not very good in maths,’ I said honestly ‘But I can add and subtract!’ He gave me a job as a junior clerk on three pounds a week, which wasn’t bad for those times. I gave one pound a week to my aunt, and spent the rest on books, films and stationery. And I bought myself a new pair of shoes, because my aunt would say, ‘A man is always judged by his shoes, Ruskin, your shoes look very shabby.’

I had never paid much attention to my appearance, and my trousers were usually unpressed, my shirt sleeves frayed, my ties ragged (you had to wear a tie to work in those days), but I made an effort to smarten myself up, both to please my aunt and to impress the girls who worked at Les Riches. I worked with some twenty other clerks, a mixed bunch, in a large, gloomy office above the store. It was winter—dark when I walked to work at eight in the morning, dark when I walked back from work at six in the evening. Saturday afternoons we were free, and of course Sunday was a holiday. My fellow clerks, most of them senior to me, were a friendly lot, who talked about football, films, the weather and the Royal Family. When King George VI died, we observed a minute’s silence. He’d been a popular king, very brave and unselfish during the war, in spite of poor health. I remember my father used to think highly of him.

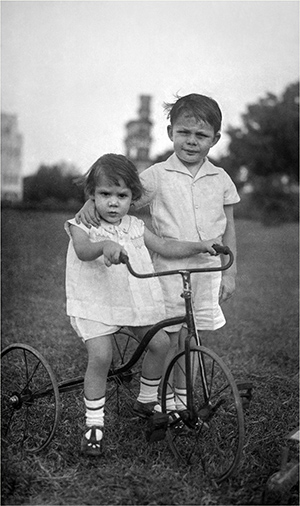

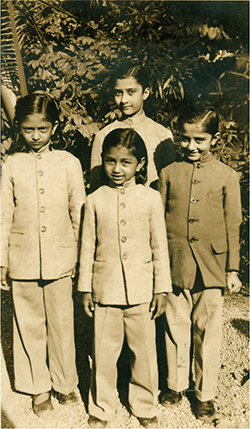

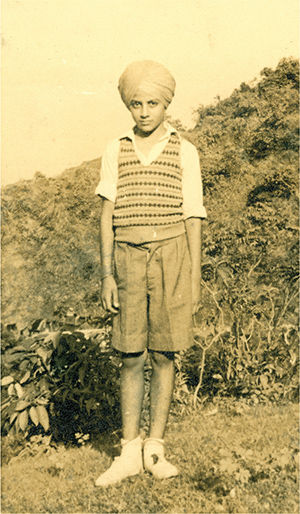

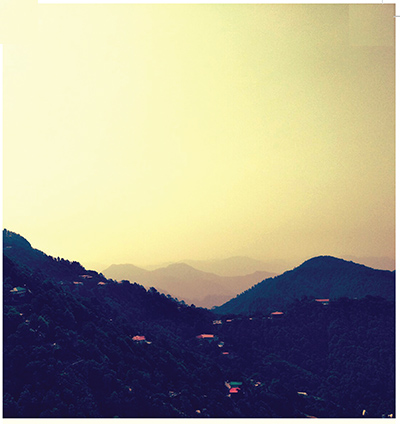

I would always miss my father, but now I was missing India and my friends in Dehra. During that last year, I had made many attachments—Somi and his brothers; Krishan and his mother; Ranbir and his sister Raj; and I missed our games and picnics and little expeditions into the foothills. And the bazaar with its sweet shops and chaat shops, and the little railway station, and the lonely mango groves, and the bulbuls and mynahs and other small birds who would visit my room on the roof. Here in Jersey, there were only seagulls! And it was an insular place. There was little here to remind me of India or the East, not one brown face to be seen in the streets or on the beaches. I’m sure it became a different sort of place in a decade or two, but in the 1950s it had nothing to offer by way of companionship or good cheer to a rather sensitive boy who had left home and friends in search of a ‘better future’.

Occasionally, after an early supper, I would walk along the deserted seafront. If the tide was in and the wind approaching gale-force, the waves would climb the sea wall and drench me with their cold salt spray. My aunt thought I was quite mad to take this solitary walk; but the fierce wind and the crashing waves gave me a sense of freedom, and some solace. Not since the year following my father’s death had I been such a loner.

The attic room I’d been given had no view, so one of my favourite occupations, gazing out of windows, came to a stop. But perhaps this was helpful, in that it made me concentrate on the sheet of paper in my typewriter. At night, I would take out my Dehra journal and put some of the entries into story form. Perhaps they would make a book of sorts. And I was writing stories and sending them to English magazines, but they came back with polite rejection slips.

I discovered the St Helier library, and lapped up the collected plays and poems of Rabindranath Tagore; a couple of novels by Mulk Raj Anand and R.K. Narayan; a charming childhood memoir by Sudhin Ghose set in the Santhal Parganas (And Gazelles Leaping ); and the novels of Rumer Godden. These books—particularly Tagore’s poems—kept me in touch with the soul of India.

One of Rumer Godden’s novels, The River , had recently been filmed by Jean Renoir, the great French director, and it ran for a week in one of St Helier’s cinemas. I saw it several times—enchanted by its lyrical intensity, its glorious colour, and the way in which it captured the atmosphere of a corner of India that resonated in my heart. I read all Rumer Godden’s ‘Indian’ novels—Black Narcissus (also a beautiful film), The River , and Breakfast With the Nikolides (possibly her best)—and resolved to capture, or recapture, my own corner of India in the novel that was slowly taking shape.

By now I had left Les Riches, and taken a job as an assistant in the newly-opened office of Thomas Cook, the travel agency. Thomas Cook had sent a representative, Mrs Manning, over to Jersey to look after their expanding travel business (hotel bookings mostly) on the island. Mrs Manning needed an assistant who was polite and who could speak good English, and I seemed to fit the bill.

One of my faults is that I am over-polite, too willing to please, and as a result I am bullied and over-ridden by strong, masterful types—particularly women. Mrs Manning was the strong, masterful type, who soon had me doing everything in the office, from making tea to answering the phone to making hotel bookings to starting a filing system to typing the office correspondence and then to going out to post it while she chain-smoked and spoke non-stop but distractedly on the phone. Sometimes she was absent for hours, for she was having a passionate affair with a smooth-talking, good-looking man who made a living from selling used fire extinguishers. He was a conman, really, and a smart one. He bought up old fire extinguishers, put them in working order, gave them a fresh coat of paint, and then drove around the island selling them as new. My boss, Mrs Manning (I never did learn who Mr Manning might have been) accompanied him on his drives around the island, which must have been fun—Jersey’s climate and scenery was just right for middle-aged lovers.

Left in charge of the affairs of a famous travel agency, I did my best to cope with an ever-increasing volume of work; but inevitably there was some confusion and several mix-ups. An elderly couple had wanted a room with twin beds—why had I given them a double-bed? And there were the honeymooners who wanted a double-bed and who’d been given separate beds. Some hotels still had a colour bar—the rest of Britain had, largely, begun to acknowledge and address its centuries-old racism, but not Jersey—and I was given a dressing-down for booking a group of Samba dancers from Brazil into a hotel meant for all-white customers.

Coming under fire, Mrs Manning fired me. A few weeks later she was recalled to London; maybe she took her fire-extinguisher lover with her. I never found out because by that time I had another job, this time in Jersey’s Public Health Department.

The idea of being dependent on others never appealed to me, and I was never without a job for long.

In the offices of the Public Health Department, close to the St Helier docks, I was in the company of several senior clerks, engineers and secretaries, and got on famously with everyone. Of the year I was with them, I have only fond memories.

I was the youngest, and everyone called me Russ—or, when they learned of my writerly ambitions, Pushkin! I remember their names—Mr Bromley, the gentlest of them all; a human chimney called Bliault (a French name—the Channel islands being originally French; most people spoke a French patois); Mr Cummings, who had been in the navy during the war; and our chief, Mr Gothard, a very nice, soft-spoken man. There was also an engineer, McLintock, a Roman Catholic, and as Catholics don’t believe in birth control, he had twelve children. I don’t know how he was managing on his salary, bringing up so many children. He was a nice man too, except that he would keep telling me I should ‘look up the Catholic faith.’ He was trying to convert me. Although a Protestant, I wasn’t into religion at all, and I let him carry on, showing no interest whatsoever, till he got the message and stopped.

I ended up spending a lot of time with Mr Bromley, a quiet, gentle man in his early fifties. A widower, he lived alone in lodgings close to my aunt’s house, and we would walk back together every other evening. He was a Yorkshireman who had settled in Jersey for health reasons. Yorkshire, he said, was too damp, which wasn’t good for him, and he’d been told by the doctors to go to a sunnier place. He did not tell me the nature of his illness; but he often spoke about his son, who had been killed in the war, and about the North Country, which was his home. He sensed that we were, in a way, both exiles, our real homes far from this small, rather impersonal island.

Mr Bromley had read widely, and he rather admired my naïve but determined attempt to write a book. I think it was he who had given me the name Pushkin, and would ask every now and then how my book was coming along.

One evening I stopped in front of a shop which had a little portable typewriter on display that I’d been admiring for some days, and I said, ‘How I wish I could buy that.’ My old typewriter was in bad shape, a couple of the keys had jammed and I had to ink the letters by hand after I had finished typing.

‘Is it very expensive?’ Mr Bromley asked.

‘It’s nineteen pounds. I only have six pounds saved up, so maybe in a few months.’ And I began to walk.

Mr Bromley stopped and said, ‘I tell you what, lad. Give me your six pounds, and I’ll add thirteen pounds to it, and we’ll buy the machine. Then you can pay me back out of your wages—a pound or two every month. How would that suit you?’

Something about Mr Bromley’s demeanour, and the rapport we had developed, made me accept his offer without hesitation. We bought the typewriter and I walked home feeling a little more confident about my writerly efforts. It took me several months to repay the loan—I kept sending some money every month even after I moved to London—but Mr Bromley was always patient.

While in the Public Health Department, I was persuaded by my senior colleagues to sit for the Jersey Civil Service exam, which was open to everyone regardless of qualifications. There were papers in General Knowledge, Elementary Maths, History and English Literature, as well as an Intelligence Test. As the reader knows, I had an aversion to exams, but Mr Bromley and the others prevailed upon me to take the exam, which I did, along with some 200 other candidates.

To my surprise (and to the astonishment of my aunt and uncle) I stood fourth in the island, with special mention of my excellent English Literature paper.

This meant that I was now eligible for a permanent post in the Public Health Department, or in any other department of the local government. There was an interview for those who had cleared the exam, and one of the men who was interviewing me said they would give me a promotion if I moved to the medical service department, where they needed people. I said I was happy in the Public Health Department; I was used to the work and the people, so I’d rather stay there. The interviewer looked a little surprised, then said, ‘Well, there’s something to be said for loyalty.’

I suppose it was loyalty of a kind. Mr Bromley and the others had been good to me, and if it was going to be Jersey and a routine job, I’d rather be among people with whom I was comfortable.

But the real reason was different. Yes, I could have settled down in Jersey and grown old there, on a comfortable salary and the prospect of a pension. Everyone would have approved—my aunt and uncle; my mother back in India; my well-meaning colleagues. But I wasn’t looking for permanency or the unexciting life of a government servant. I didn’t refuse the permanent job, but in my heart I knew I wasn’t going to stay.

Encouraging noises were coming from a publisher in London, who had read the first draft of my novel. Her name was Diana Athill, a partner and editor in the firm of Andre Deutsch Ltd., an up-and-coming publisher. She was enthusiastic about the book, but she felt it needed some re-working, and she had suggestions to make. And I have always been open to suggestions.

London beckoned. That was where writers and publishers flocked together. That was where Dickens had lived, and Thackeray, and Galsworthy, and dear old Hugh Walpole, a brave man, and a friend to young writers. That was where Barrie was commemorated with a statue of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. That was where Bertie Wooster and Jeeves and the members of the Drones Club indulged in the festive spirit. Or so I imagined…

But the real impetus or catalyst to my leaving Jersey was a falling-out with my relatives, specifically my uncle.

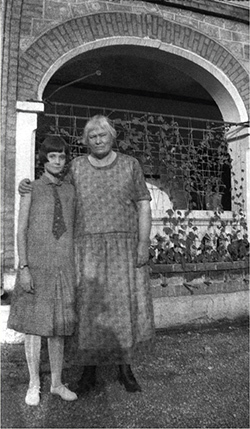

A Christian from Pondicherry, Dr Heppolette was upright, honest and hardworking (and he’d been a well-known doctor in Lahore), but he was set in his thinking and his prejudice against the country of his birth. He did not think much of India or of Indians, and frequently expressed the gloomiest of forebodings on the future of the country, just five years into Independence. He was also very vocal about his disapproval of my mother and the life choices she had made, ending up with an ‘Indian’. Both he and my aunt had led a privileged existence in British India, and had left because of the loss of privilege. There were many like them. I felt that his attitude was unfair, and said so; but because I was living with them as a ‘poor relation’, even though I was paying my way, I did my best to avoid heated arguments or any unpleasantness. Instead, I put down my thoughts and feelings in the diary I was keeping. Unfortunately—or fortunately, I suppose, now that I look back—it fell into the hands of my uncle, who couldn’t resist reading it, and we had an almighty row. Among other things, I was accused of ingratitude, and that by itself convinced me that I ought to move on.

Whenever I was unhappy or disturbed, I used to go for a walk along a lonely stretch of seafront, and that was what I did now, although it was late evening. There was a storm brewing and the waves were crashing in and there was nobody else on the seafront. The tide was high, and a wave smashed itself against the sea wall, sending the salt spray on to my head and face. I almost lost my balance, but I stood my ground, and then I stood defiant, taking another stinging spray on my body, and then another, as the wind howled around me, testing and daring me. It was an exhilarating sensation, guaranteed to make me feel brave and indomitable—I would survive. With the help of the natural elements around me, I resolved, there and then, that I would leave Jersey the next day.

And this is exactly what I did.

Suitcase in one hand and portable typewriter in the other, I made my way down to the docks and bought a ticket on the first small steamer leaving for Plymouth. I hadn’t even bothered to give notice to my employers, and as a result I lost the previous week’s salary. But I had about twenty pounds saved up, and in 1952 that would have kept me from starvation for about a month.

It was March, and the Channel was foggy, and the sea choppy. But I felt quite confident in myself and in the future. I suddenly realized that for the first time in my life I was really and truly on my own. No parents to back me, no relatives to fall back on. Alone. All by myself in a wilderness of wind and water. The way I wanted it. Eighteen, and in control of my own destiny. For that man is strongest who stands alone.

I DIDN’T SEE MUCH OF LONDON FOR THE FIRST COUPLE OF DAYS, the fog was so thick and all-pervading. I spent two or three nights in a student’s hostel; it was cheap, but very noisy. I had the address of an old BCS boy, Shyam Kishan, who was in London for ‘higher studies’. He had a room in Belsize Park, and he insisted that I stay with him. He had been my senior in school, not a very close friend, but now he treated me like a brother. But I knew I had to fend for myself, and at the first opportunity I made my way to the nearest employment exchange and asked for a job.

I must have looked rather shabby. My trousers, as usual, were unpressed, my coat—the only one I possessed—a bit worn at the cuffs, my shoes unpolished. I had no overcoat, and I was feeling cold.

‘And what can you do?’ asked the clerk, looking at me doubtfully.

It was no use telling him that I’d written a book. They weren’t looking for an unemployed author.

‘I can type,’ I said. ‘I can write letters. I can make out bills. I can do accounts.’

‘Quite an all-rounder,’ he remarked, laughing. ‘Anything else?’

‘I can play football.’

‘Can’t help you there. You’ll have to join a football club. But there’s this factory in Swindon that makes football boots. Would you like to work in a boot factory?’

‘No, sir.’

‘All right, so here’s a desk job for you,’ he said, taking a card out of his index cabinet. ‘Photax, Photographic Accessories. They need an accounts clerk who knows some book-keeping. Starting on five pounds a week. That suit you?’

Five pounds a week sounded like a fortune. In Jersey I’d been getting three pounds.

‘Sounds all right.’

‘Here you are, then.’ And he gave me the address of Photax Ltd, who were to employ me in their office off Tottenham Court Road for the next two years.

Shyam, whom we knew in school as ‘Jackson’, which was the name of the high-end garments shop his father owned in Jodhpur, insisted that I could stay with him as long as I liked. But I didn’t want to impose on his goodness and hospitality. I went out and found a room for myself.

I moved around a fair amount during my stay in London, and that restlessness must say something about my state of mind at the time. First, there was a small attic room on Glenmore Road in north London, not far from the Belsize Road tube station and within a short distance of the Everyman Theatre, a small cinema which showed revivals of old films, and where I often spent a lonely evening. But the Glenmore Road room was cold and miserable, and it had a view of the overcast sky and the roofs of other houses—an endless vista of grey tiles and blackened chimneys, without so much as a proverbial cat to relieve the monotony. So I moved to a more pleasant abode on Haverstock Hill, where I lived for some months; then, for short spells, to lodgings on Belsize Avenue, Tooting, in south London, and Swiss Cottage in north London again.

Most of my landladies were Jewish. The first, whom I remember best, lived on the ground floor, two floors below my attic room. The only telephone in the building was outside her room, and occasionally when there was a phone for me, she would shout to call me down. But she could never pronounce my name right! ‘Rooskin!’ she would shout. ‘Roo-oo-skin. Call for you.’ And I would climb down the stairs, in no great hurry, because in those early months there were hardly any people I would have wanted to spend time with. I usually came back to my damp and sparsely furnished room to make myself a cheese sandwich—occasionally with ham—and then sit at my typewriter to work on my Dehra journal. Alone, till one day I noticed a roommate—a little mouse peeping out at me from behind the books I had piled up on the floor (I had no bookshelf). I threw him some crumbs and a bit of cheese from my half-eaten sandwich, and soon he was making a meal of them. After that, he would present himself before me every evening, and I was happier for the company.

My worldly possessions had increased, not only by the typewriter bought in Jersey, but also by a record player which I had bought second-hand from a Thai student, a friend of Shyam’s. I had become an ardent fan of the Black singer Eartha Kitt, and had bought many of her records; but they were no good without a player until the Thai boy came to my rescue. Then the sensual, throaty voice of Eartha—singing ‘Uska Dara’ and ‘I Want To Be Evil’—reverberated through the lodging house, bringing complaints from the landlady and the gentleman on the first floor. I had to keep the volume low, which wasn’t much fun. I was also fond of the clarinet (turi) playing of an Indian musician, Master Ebrahim, who did versions of popular Hindi film songs which transported me back to the streets and bazaars of small-town India.

On weekends I would explore the city, usually on foot, that being the best way to get to know a place. My conception of what London would be like was based on my early reading of Dickens and P.G. Wodehouse. Well, the London of Dickens was long gone, and the London (and England) of Wodehouse had never existed. There was more of the real world in Alice in Wonderland than in the world of Jeeves and Bertie Wooster. I would have gained a better idea of the city from the stories of Arthur Morrison (Tales of Mean Streets ) and Patrick Hamilton (Hangover Square ); but I came to these writers much later.

London was still recovering from the war, and in the East End and dockland there were still bombed-out buildings and empty sites where there had once been offices or residences. Sugar was still rationed, and I soon got used to the strong, sugarless office tea. Meals in the cheaper restaurants were on the skimpy side, and when I had finished my ‘meat and two veg’ in the nearest ABC café, I was still very hungry!

Still I tramped around the city whenever I could—searching the Thames dockland and the Mile End Road for traces of Bleak House or Our Mutual Friend . Dutifully I wandered through Kensington Gardens and paid homage to the statue of Peter Pan, took up my position on a corner of Baker Street and looked across at the entrance of the house where Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson had met so many mysterious clients…

In the evenings, I usually took the tube train home after work from Tottenham Court Station to Belsize Park. Sometimes I walked. One evening I started walking through the maze of streets and I saw a little roadside restaurant and decided to have dinner there, having tired of cheese and ham sandwiches. I’d never been there before. I walked in, sat down, had a nice, good meal, and when it was time to pay the bill I found I didn’t have my wallet on me! It was getting towards winter and I’d kept it in my overcoat, which I’d left hanging in the office. I fiddled with the cutlery for a while, then decided to come clean. I went up to the manager and said, ‘I’ve had my dinner, sir, and it was very nice. But I don’t have any money with me. I’m sorry, I’ve left my coat in the office with my wallet in it.’ I told him where I worked, not far from the restaurant, on Goodge Street, but the office would be closed now. He looked me up and down, assessing me to see if I was telling the truth or pulling a fast one, and then he said, ‘All right. You can come by tomorrow and pay the bill.’ Which was what I did, first thing the next morning.

I would go to the restaurant once in a while after that in the evenings. During the day, a fellow clerk at Photax, Ken Murrel, would share his marmite sandwiches with me, made by his mother, or we would go out together to a snack bar during the lunch break. Ken was always very helpful; working class himself, he could tell that I was having a harder time. We exchanged a few letters soon after I returned to India, and then there was a period of some forty years when we didn’t correspond. About ten years ago, I received a letter from a man, who wrote to say he had my address from his father—Ken Murrel. Ken had been suffering from Alzheimer’s and barely recognized anyone. One day his son told him he was going on company work to a town in India called Dehradun, and Ken’s eyes lit up and he said, ‘That’s where Ruskin went, you know. He’s my friend.’ It was very touching to read that. Ken’s son came up to meet me from Dehradun, and I shared my memories of working with his father when we were both young, just nineteen or twenty.

But I did not make many English friends. If they were a reserved race, I was even more reserved. Always shy, I waited for others to take the initiative. In India, people will take the initiative, they lose no time in getting to know you. Not so in England. They were too polite to look at you. And in that respect, I was more English than the English.

The gentleman who lived on the floor below me on Glenmore Road occasionally went so far as to greet me with the observation, ‘Beastly weather, isn’t it?’

And I would respond by saying, ‘Oh, perfectly beastly,’ and pass on.

It was all very polite and insular, and rather dull. Things changed when I bumped into a Gujarati boy, Praveen, who came to live on the basement floor. He gave me a winning smile, and I remember saying, ‘Oh, to be in Bombay now that winter’s here,’ and immediately we were friends.

He was eighteen, and studying at one of the polytechnics with a view to getting into the London School of Economics. At that time, most of the Indians in London were students, the great immigration rush was still a long way off, and racial antagonisms were directed more at the recently arrived West Indians than at Asians.

Praveen took me on the rounds of the coffee bars, and introduced me to other students, among them a Vietnamese, called Thanh. He would become the subject of one of my stories, as would a distant cousin of his, a girl named Vu, and both relationships would end in some disillusionment, but more of that later.

Praveen liked gangster films and wanted me to accompany him to anything which featured Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, George Raft and other tough guys. He wanted to be a tough guy himself, and often struck a Bogart-like pose, cigarette dangling from the side of his mouth. There was nothing tough about Praveen, who was really rather delicate, but his affectations were charming and comic and it was fun being with him.

From the room in Haverstock Hill, my second abode in London, it was a short walk to Hampstead Heath, the large park in London with its ancient woodlands and chain of ponds, and on one occasion I walked from Primrose Hill down to Regents’ Park. There was no shortage of greenery and parkland in London, and I wrote a story called The Green City which was never published, in fact lost by a future publisher.

Not much was being published, not even by the ‘little’ magazines to whom I submitted the odd poem. This prompted me to write the following verse:

Who’ll buy my poems?

I sang out to the silent stones.

And came the dread reply

In deep sepulchral tones:

We’ll buy your eyes

We’ll buy your heart and bones

We’ll buy your rags

And settle all your loans

But please don’t send us any poems,

We will not buy your rotten poems!

Needless to say, no one published it. Even Punch did not find it funny.

However, I had better luck with radio.

Dear old BBC. I was finally repaid for all my years of loyalty in listening to ITMA , Much-Binding-in-the Marsh , and Waterlogged Spa , not to mention the endless cricket commentaries, by having a story accepted and broadcast on the Third Programme, which was aimed at highbrows and super-intellectuals, which I definitely was not, but the producer, a nice lady named Prudence Smith, assured me I could pass for one. The story was called ‘The Rainbow,’ and I was invited to read it live, a daunting prospect; but I did it with aplomb after some rehearsals with the producer!

I no longer have the script; but it was to become one of the early chapters of The Room on the Roof —the episode in which Rusty plays Holi with the local boys and begins his discovery of India.

My employers at Photax were impressed (there was no one else to impress) and gave me leave to give two more talks, these on the more popular Light Programme—one of them about growing up in India (called ‘My Two Countries’), and another about life in the bazaars of an Indian city. The producer of this programme was a kind man called P.H. Newby, a well-known novelist and travel writer. Over the years, and even after my return to India, the BBC was to provide a home for many of my short stories.

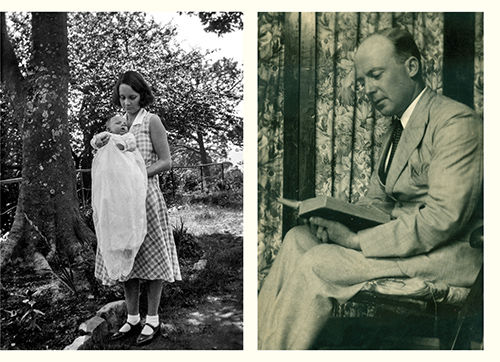

A small digression at this point, to describe a brief encounter that shows how different the life of a writer was fifty or sixty years ago, before the advent of television and the internet, when only film or sports stars and popular singers, or the occasional fashion model, were celebrities. Even newspapers did not write about them so much as they did about their books (book covers were photographed more than the authors).

I was outside one of the BBC studios, waiting to give my talk, when a man came out of the studio, greeted my producer, passed the time of day with him and me and then left. I don’t remember what we talked about—could even have been something as mundane as the weather. Anyway, after he left, the producer asked me, ‘You didn’t know who that was?’ and I said no. ‘That’s Graham Greene,’ he said.

Greene was then at the height of his fame. He’d even done the screenplay recently for The Third Man , which was running in the West End. He was a nice-looking man, but understated, and not immediately recognizable. He wasn’t a public face. And you could have said that about most authors at the time. Except for those who sought out publicity—someone like Hemingway, who liked being in the public eye and would do things like crashing his plane somewhere in Africa in order to get into the newspaper headlines.

But let me return to my BBC stories. Another to be impressed by this little achievement was Diana Athill, of Andre Deutsch, who had been corresponding with me in regard to The Room on the Roof , which she had first read as a journal and suggested that I rework it as a novel. It was now in its second or third draft—what started out as a journal became a first-person fictional narrative, and finally ended up in the third person. Diana would send me feedback—her own, and from the firm’s ‘readers’—which was sometimes useful, and sometimes contradictory and confusing. But I did benefit from much of it, especially Diana’s suggestions, which were about the story; she did not tamper with my language or style.

To give the reader some idea of how the novel evolved, and what a good editor’s engagement with a young writer’s work can be like, let me reproduce one of Diana’s letters to me. (In the draft of The Room on the Roof that Diana is responding to in this letter, Kishen had become Kamini—purely a literary sex change—but reverted to Kishen in the final draft.)

March 6th 1954

Ruskin Bond, Esq.,

124 Haverstock Hill

London N.W.I

My dear Ruskin,

I have read The Room (and it must be The Room—it is the inevitable title for it), and I like it. I gave it to someone else to read yesterday, and they brought it back to me saying ‘I think it’s a lovely story’. Andre hasn’t read it yet, however, so you will just have to make do with this much at present.

I am not without criticism, however, and two I can give you straight away. 1. The end is a bit too fairy-tale. The coincidence of your meeting with Kamini by the river strains the credulity at a point when it is absolutely vital that it should not be strained. I thought that this could be avoided fairly easily by making something like this happen. Perhaps a neighbour to the house where she had been with her mother in Hardwar could chip in and say that she had an idea where the girl might be found—she had felt sorry for her, and had tried to help her, but Kamini had not accepted it (excepting, perhaps, for once or twice taking food from her) and had slipped off into the town: but she had seen her about occasionally, and thought that she often hung about the steps to the river … You could still be pretty hopeless about finding her, and so have the hopeless feeling of page 121, but when you did find her it would not make the reader feel ‘how very convenient!’ in that disturbing way.

The other thing is that you have been too ruthless in your pruning away of inessentials. What you have done, in fact, is write as though your medium was the short story, not the novel. You don’t give time enough time to pass in! (I’m not sure that that isn’t a meaningless remark!) What I mean is, that some incidents and people could be, perhaps, a little enlarged, so that the reader had time to settle down in them. Particularly, this applies where you first go to live with Somi. This is a crux point, new life, and you dismiss that week in a page or two. I think you could enlarge here quite a lot, with benefit. Somehow the feeling of strangeness and excitement at the small things being different, the eating and the sleeping and the washing… You are taking your reader from one world (superficially speaking) into another, as well as yourself, and you must allow them more time to get the feel of it.

I wonder what you will feel about that. Does it make sense to you?

I shall try very hard to get you the final decision as soon as possible, and no doubt we’ll be talking more about the book soon. Meanwhile, I do think you have done wonders.

Yours,

Diana

P.S. I’ll tell you one thing that I missed—the original Kapoor family. You’ll begin to wonder why I don’t sit down and write the book myself, soon; but couldn’t Somi’s family have such neighbours, who could come into that chapter? Kishen could still be their spoilt son. Your pupils rather materialize out of thin air, as it stands, and they would be more explained if you had two families backing you as a teacher, and telling people about you. And that old drunk father was a good solid character—an excellent filler in of atmosphere and background.

I must say I worked harder on that book than on anything else I have written; and there was a time when I thought it had all gone to waste. Because Deutsch just could not make up his mind about it. His readers (Walter Allen, the famous critic, and Laurie Lee, the writer) said it was full of promise but that it would be premature to publish a work that was, in many ways, still immature. They were probably right; but I think that ‘immaturity’ was one of the appealing things about the book, for it was, after all, a story of adolescence written by an adolescent.

Anyway, it led to several meetings with Diana Athill, and our enduring friendship. She was sixteen years older than me, and I wasn’t really her type, and I was past the stage of puppy love, so there was no question of a romantic or physical relationship. I looked upon her as a literary person, even as a mentor, which she was, and then as a smart and sensitive friend whose company I enjoyed. She was fond of me, and she could see I was neglecting myself, so she would invite me to her flat sometimes and share her meals with me—wholesome English food she cooked herself. When it grew very cold, she gave me an overcoat.

Many years later, Athill took to writing herself, and published a series of remarkable memoirs (the last of these at ninety-eight). In some of these she describes her life with several lovers, and writes about being ‘the other woman’ very often and finally going off sex at age seventy-five. But at the time I knew her, I did not see evidence of this. She was sharing her York Terrace flat with her cousin Barbara, who was working for The Economist , and it was Barbara who was having an affair with a writer called Anthony Smith—who was having an affair with a hot-air balloon. He took off in his balloon and landed somewhere in Iran or Afghanistan. However, he came back to write a book about it, and to marry Barbara.

On a couple of occasions, I took Diana to an Indian restaurant—there were only about half-a-dozen to choose from in the London of the 1950s—and sometimes we went to the cinema together. We usually went to see French films, which had English subtitles. After I took her to see a particularly silly film called Aan —the first Indian feature film to be shown in London—she became a bit wary of my choice of films, but got her revenge by taking me to see Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and the unfinished Que Viva Mexico. The latter had been edited by Marie Seton, whom I was to meet in Delhi and Darjeeling several years later, when she was working on her biography of Satyajit Ray.

A film buff from my time in Delhi with my father, I explored the suburbs of London, visiting cinemas which were showing offbeat films that might not have benefited from a West End release. And when I had some money to spare, I went to the theatre. I saw a great production of Porgy and Bess , brought to perfection by the two great Black singers Leontyne Price (singing ‘Summertime’) and William Warfield (‘Bess, You Is My Woman Now’), and by an old film favourite, Cab Callaway, with his rendering of ‘Ain’t Necessarily So’.

The old Scala theatre was close to the Photax office on Charlotte Street, and around Christmas time I dropped in to see the annual production of Peter Pan , Barrie being one of the playwrights whose plays I had lapped up when I was at school. Playing Peter was Margaret Lockwood, one of the most popular British film stars of the 1940s; not so young any more, but still beautiful and very accomplished. I was the envy of my office colleagues. Most of them lived in the suburbs and went straight home after work. Also, they saved their money, whereas I spent mine.

The movies and musicals provided some relief from the otherwise monotonous routine of near-endless hours in the office, followed by hurried sandwich or beans-on-toast dinners and a lot of typing and revising of my manuscript. After a year of drudgery, juggling with figures (no calculators and no decimal system as yet), I stepped out of that office looking for a different sort of life. And in due course I found it.

TODAY, AS I LOOK OUT OF MY WINDOW AT THE MOUNTAIN MIST curling up from the valley, I am reminded of a different mist—not so much the London fog of 1953, as the mist that was gradually obscuring the vision in my right eye.

It began with black spots that kept dancing in front of my eye, like Fred Astaire in top hat and tails. Well, we all see spots from time to time. But these were there in all my waking hours—in the office, on the streets, in cinemas, restaurants, and in my little room. They were very irritating.

‘It’s probably due to malnutrition,’ I told myself, and began dosing with vitamins.

But gradually the spots grew bigger until they coalesced into a shifting cloud, and there wasn’t much else that I could see with my right eye.

Fortunately, the left eye was unaffected, and I used it to guide me to the consulting room of an eye specialist. After various tests and examinations, which involved several visits, he declared that I was suffering from ‘Eale’s Disease’, a rare condition of the retina, and had me admitted to the Hampstead General Hospital for further observation and treatment.

I spent a month in the general ward, a guest of Her Majesty’s Government and the National Health Insurance, which meant I did not have to pay a penny for my stay and treatment. The latter consisted of cortisone injections to the eye, and a diet designed to build up my resistance to infection—for I was right in thinking that malnutrition was at the root of my problem. For almost a year I had been living on Mars Bars, beans on toast, cheese sandwiches, and the occasional ‘meat and two veg’ dinner. I had never been so skinny in all my life. And now, to the envy of the other patients in the ward, I was provided with a bottle of Guinness (light ale) with my substantial lunch. This was designed to buck me up—and it did! ‘God bless Her Majesty’, I toasted the Queen as I gulped my Guinness, although I should really have been blessing the Labour Government, which had just been voted out of power.

While recuperating in the Hampstead General, I wrote a story and read several books, brought to me on a trolley every morning. I discovered the detective novels of Josephine Tey, and a book on the Buddha (by Robert Payne) which helped me to take a philosophical view of my situation. I received visits—Diana Athill (with flowers), my new landlady (with a cake), and my office manager (with my salary packet). As I had no expense at all that month, I had saved twenty pounds of my salary.

My vision did improve slightly. The cloud dispersed. But it never went away completely, and even today I do not see much with my right eye. Well, as long as my left eye and my writing hand continue to serve me well, I consider myself lucky, or rather, blessed by a benign providence.

And in London there were soon to be other distractions.

One of the patients in my ward in the Hampstead General hospital was George, a man of about thirty who had come to England from Trinidad and worked as a ticket-collector at one of the underground stations. He had been suffering from fever and a stiff neck and the doctors suspected meningitis. He was a large, stout man with a gentle, kindly expression on his mobile face, and he was always smiling—except when he had to be given a rather painful lumbar puncture. He would set up quite a commotion then, and I would go over and sit on his bed and try to calm him down. When I left the hospital, I gave George my home address, although I didn’t expect to see him again.

A few months later, I found him on my doorstep, fully recovered and smiling. We repaired to a nearby pub and drank rum. He invited me to a party in Camden Town, and when I arrived, I found I was the only ‘white’ in a gathering of handsome Black men and women determined to have a good time. We drank and danced into the early hours of the morning, when I fell asleep on a sofa, and someone fell asleep on top of me.

I went to two or three more of these calypso parties—I didn’t really have the stamina to become a regular—and George and his friends poured sunshine into my rather dreary life.

And then, along came Vu.

Or rather, her cousin Thanh, who introduced me to her.

Thanh was a Vietnamese youth of my age, but younger-and better-looking, delicate and androgynous. His family was well-to-do, and lived in France (Vietnam had been a French colony and many Vietnamese had settled in France). He was in London because he wanted to be a pianist and he wanted to speak English fluently. Both his piano-playing and his English were rudimentary. He had met Praveen somewhere, and when Praveen told him that I was a writer of sorts, he turned to me for help with his English.

Thanh was a complicated person, but I didn’t see this at first. I was attracted by his exotic looks and a sort of sophisticated aloofness he cultivated. He didn’t like Asians very much, though he was one himself, and when I told him I was Indian—very much an Asian—he looked disappointed but seemed to get over it. He said he liked me, and despite myself I was flattered. We grew close; I stayed with him in his rooms and enjoyed his cooking—he was a better cook than a pianist—and conversed with him in English.

Sometimes he would complain that I wasn’t a good friend, that I did not respect him, and thought too much of myself though I knew so little and spoke English like a Welshman, not a proper Englishman. But he would turn affectionate soon after and cook me delicious pork and fried rice.

Sometimes he would be gloomy and tell me he didn’t have long to live.

‘There is something in my chest. It is always ticking,’ he would say and bare his bony, pale chest for me. I would put my ear to it and hear nothing. I would ask him to go to a hospital and get an X-ray done, but he would turn away in irritation.

Our association ended abruptly one day when he realized my accent wasn’t even Welsh—as, I later gathered, Praveen had told him—but Indian. He felt that I had betrayed him in some way. Indians, he said, were not to be trusted.

‘Find someone who can speak real English,’ he demanded. ‘Otherwise you are not my friend.’

So I introduced him to a boy who spoke ‘real English’—a Cockney youth who worked for the British Railways. They hit it off splendidly, and months later dear Thanh was speaking pure Cockney. I suppose I’d had my revenge.

Before he terminated our friendship, Thanh had introduced me to Vu Phuong—a pretty, petite, sweet, intelligent nineteen- or twenty-year-old, who was on her own in London, studying something or the other—it was a mystery to me what some of these young people were studying, they seemed to have an endless amount of time on their hands. But at least Vu did not ask me to teach her English. She knew enough to be able to charm anyone who met her. And I found myself at ease in her company. This was unusual, because I was usually shy and self-conscious with girls of my own age.

Vu liked visiting parks and public gardens, and I was quite happy to accompany her on these little expeditions—strolling through Regent’s Park; feeding the ducks at the pond on Hampstead Heath; lying on the grass on Primrose Hill; exploring the hothouses at Kew.

The botanical gardens at Kew always attracted me, because there I could return to the tropics simply by entering one of those steamy hothouses where tropical plants grew in profusion. It was the Amazon basin rather than the Ganges plain that was re-created here, but that was good enough for me; anything to get away from the London drizzle and the fogs that came in from the Atlantic.

‘We’ll go down to Kew in lilac time,’ were the words of an old song, but I was glad to go down to Kew at any time.

On Primrose Hill, Vu took my hand and held it seemingly for ever, and naturally I fell in love with her. It was the first time a girl had shown me undisguised affection and a desire to be with me. I did not take her back to my rather gloomy room (my landlady had forbidden visitors), but she took me to hers (no sign of a fearsome landlady) and we spent hours together, drinking tea and playing simple card games. I must have been madly in love with her in order to play cards; I hated card games—my time with Miss Kellner being the only exception. But during those idyllic few weeks I was ready to do anything to please Vu.

We drank innumerable cups of chrysanthemum tea, and told each other’s fortunes from the tea-leaves. You need proper tea leaves for this, not tea-bags. When the leaves settle at the bottom of the cup, they take on unusual shapes and patterns, and those who can interpret these patterns predict the future from them. Vu was an expert at doing this, and predicted all sorts of interesting things for me—that I’d be a successful writer some day (but not in the near future), that I’d travel to distant lands (maybe India, maybe Africa), and that I’d have many love affairs.

‘Never mind the love affairs,’ I said. ‘What about us—will you marry me?’

She studied the tea-leaves in her cup for some time and said, ‘It’s not in the tea-leaves. So sorry.’

‘Try again. Read my tea-leaves this time’.

So she studied the pretty chrysanthemum leaves at the bottom of my empty cup, and made the same pronouncement: ‘So sorry, Ruskin. It’s not in the tea-leaves.’

After that I refused to look at the tea-leaves.

She really was a lovely person, and I was deeply in love with her. But it often happens that I overdo things, get carried away by my infatuation or passion and make a mess of everything. I finally taught myself to take things somewhat lightly, not to scare people away with the intensity of my feelings, and even to have no expectations from others, but it took me many, many years.

When Vu told me that she was going into the country for a couple of weeks to pick strawberries with a group of students, I should have left it at that. Strawberry-picking was an annual ritual with foreign students who made a little pocket money working on farms in the English countryside. But a week without Vu was too long for me. I knew where they’d gone—a village called Kintbury in Berkshire, only an hour or two from London—and on a desolate weekend I bought a rail ticket and travelled up to Kintbury.

It was a pretty little place, Kintbury, a real old-fashioned English village, with a homely pub decorated with prints of hunting-scenes. I had a light lunch, and set off for the farm where I was told the girls were staying.

I found them all right, all gathering strawberries—pink-cheeked English girls, tall willowy Scandinavian girls, handsome smiling African girls—and Vu in the middle of them, having the time of her life.

I don’t think she was pleased to see me—she’d have to explain my sudden arrival to all her companions—but she was never unkind, and she greeted me with her usual sweetness and asked me why I was there.

‘Just wanted to see you,’ I said.

‘Well now we have seen each other. I have to be with the girls. You go back to London and I will see you next week.’

I went back, feeling rather foolish. I called at her lodgings the following week but was told by her landlady that she had not returned. Three days later, when I telephoned, I was told that she had moved elsewhere. The landlady wasn’t sure where. Somewhere in South London—Tooting or Clapham—she was very vague about it. I had changed my own lodgings several times, but I had always lived mostly in north London. Except for Kew Gardens, south London was unfamiliar territory to me.

Disheartened and downcast, but still hopeful, anxious to clear up any misunderstanding and reinstate myself in Vu’s affections, I made a serious attempt to locate her. A sympathetic Thai student gave me an address, and off I went to track it down. I had a fortnight’s leave that year, and I spent most of it in a frustrating endeavour to find Vu Phuong, to whom I had surrendered my heart.

It was clear that she no longer wanted my heart, if she ever had at all, but I persisted. Was I becoming a stalker? The thought did not occur to me then, but looking back, I feel I came near to being one.

At the new address I was told that Vu and her student friends had gone to Paris. Apparently her sister ran a restaurant there. I walked across the street and spent some time walking up and down the pavement. I had a feeling that Vu was in the house. And when I crossed the road and looked up at the building, I saw her face at one of the windows, looking down at me. She withdrew as soon as I raised my hand to wave to her.

I walked away, and took the train back to London. Walking back to my empty room from the Swiss Cottage station, I stopped at a pub and had a few brandies, but of course that didn’t help.

Some days later, I received a postcard from Vu, telling me that she was with her sister in Paris, and they might go back to Vietnam. Obviously I did not fit into her scheme of things. There would have been no future for me in her country, and I suppose she saw no future with me. I tried to forget her. But it wasn’t easy.

She held my hand on Primrose Hill,

I loved her then and love her still.

Although she had sworn we never would part

She went away with the shreds of my heart.

But I loved her then and love her still,

And I see her still climbing up Primrose Hill.

It was a year of disappointments, and Andre Deutsch did not make things any better by refusing to make up his mind about The Room on the Roof . He’d given me twenty-five pounds as an option on the book, and I was supposed to receive another fifty pounds as an advance against royalties. But he hesitated to commit himself to publication—he thought he would lose money on the book (after all, it was a first novel by a complete unknown), and he felt, too, that I should wait a year or two before making authorship my profession.

I wasn’t the only writer with whom Andre had trouble making up his mind. None other than Orson Welles, the great director who had transformed cinema with Citizen Kane , had come up with a novel called Mr Arkadin , and it appeared that nobody at Deutsch wanted it! Orson Welles may have been a great film-maker (though not always), but as a writer he was something of a flop. But you couldn’t tell him so. He was a big man with a bad temper. And like most actors, he was extremely vain. A polite letter of rejection was mailed to him. His response was to come storming into Andre’s Thayer Street office, denouncing two-bit publishers and their lackeys in no uncertain terms. Chairs were overturned, manuscripts flew out of windows, and poor little Andre Deutsch (who was only five-and-a-half feet or thereabouts) dived for cover. (I received a blow-by-blow account from Diana a few days later.) In the end Andre agreed to publish the wretched book.

I suppose that’s one way to get your masterpiece accepted—terrorize the unfortunate publisher.

Andre and Diana were right in thinking that Mr Arkadin had little merit as a novel. The book never really took off, and when Welles obstinately transferred it to the screen (in the process wasting the talents of some good actors, including Michael Redgrave), it did no better; the master had clearly lost his touch.

As a publisher, Deutsch was going from strength to strength, roping in such writers as Jack Kerouac, Wolf Mankowitz, Mordecai Richler, and, a little later, V. S. Naipaul and his talented but short-lived brother Shiva. But of my little book there was no sign—though I did finally receive the fifty-pound advance—and I began to see the future as year after year of totting up sales figures for Photax Ltd., good people though they were. Surely I could do as much, if not more, back in India, where I would at least have friends to cycle around with, and the freedom that comes from being a nobody in the great grey multitude that makes up the country.

For some time I had almost resigned myself to a lifetime of clerical servitude—it would have been bearable had there been someone, a Vu Phuong, to take my hand occasionally—but now, once more, I began to think seriously of returning to India; although, when I mentioned this to anyone—Indian students, my mother, or friends back in India, they expressed alarm at the thought and did their best to dissuade me. What was the point in coming all the way to England if I was going to return home because I felt lonely and because I thought I was a failure?

‘Home’—that was the magnet. Not the ‘home’ of my mother and stepfather, but the larger home that was India, where I could even feel free to be a failure. The Land of Regrets, someone had called India; but for me it was a land of acceptances. For hadn’t I, a mixed-up colonial castaway, an accident of history, found acceptance on the streets and in the tea-shops and the wayside haunts of Dehra? I wasn’t looking for a palace or a hilltop retreat. All I really wanted was my little room back again.

I left London without any planning; I made up my mind on the spur of the moment. I gave my office a week’s notice, and they had a little party for me, gave me a travel bag, and the head of the office said if I changed my mind and returned to London, I could have my job back.

Diana Athill didn’t know I was leaving. She found out only when I wrote to her from Dehradun to tell her, ‘So I’m back in India. Are you going to publish my book?’ I suppose I should have behaved better after all the kindness she had shown me, and gone and met her before I left London for good. But I did hear back from her some months later, when she sent me copies of The Room on the Roof . We still write to each other every eight or ten years (Diana will be a hundred this winter; 2017).

From Vu I heard nothing more. Her life, it seemed, was to go in another direction—to war-torn Vietnam, where her parents were still living in Hanoi, the Communist stronghold. Or she stayed on in Paris; perhaps she came back to London. I never found out.

Thanh died shortly after I returned to India. A common friend wrote to tell me it was something to do with his heart. A stopwatch had been ticking away in his chest after all. He had died in Paris, looked after by his sister.

The voyage back from England was on a cheaper liner than the one that brought me to the country. It was a Polish ship, the Batory , which had been in the headlines just some weeks earlier because most of the crew had taken political asylum in England.

My cabinmate was an Indian student, Raghuvir Narain, who was coming back home for a break. We discovered a cheap but rather nice Polish vodka in the bar, and would pool our money to buy a couple of drinks every other evening. When we stopped in Gibraltar, we went ashore together and spent some time walking around. There were a lot of shops and almost all were Indian-owned—even at that time, 1956. At Port Said, we went ashore again, and were cheated—it served us right—by a couple of Egyptian men who promised to take us to a place where a woman and two donkeys did intimate things to one another. We returned to the ship considerably poorer, having bought the men many rounds of drinks before realizing we’d been had.

The Batory was a jinxed ship. As we were passing the Suez Canal, a crew member jumped overboard and was never seen again—it was a Communist ship and the man was probably desperate to get away. Some days later, when we were in the Arabian Sea, the ship’s alarm bells began to ring in the middle of the night and there was much panic; no one knew what was happening; and hardly anyone knew how a life jacket should be worn, as there’d been no lifeboat drill. There were shouts of ‘Abandon ship!’ and then ‘Man overboard!’ and some children had begun to wail. Someone said the ship’s engine had gone silent, and it did appear that we were drifting in the immensity of darkness and sea. Finally, we were told it was a false alarm and we could go back to our cabins. We later heard that a passenger had fallen overboard. Who it was, or how he or she had ended up in the sea, we never found out.

Our last stop before Bombay was Karachi, where again I went ashore, already feeling I was home. I bought some Karachi newspapers to see if there were any I could send my stories to for publication, but the few that I picked up didn’t seem to have any space for stories or essays. I never did manage to get published in any papers in Pakistan,

Then we were in Bombay’s Ballard Pier. And as we were getting off, a fire broke out on the Batory. People rushed out while the Bombay fire brigade trucks drove into the docks with their bells ringing. I was glad to be off that ship!

This time I didn’t stay in Bombay. I went straight to the Bombay Central Station and took the slow train to Delhi.

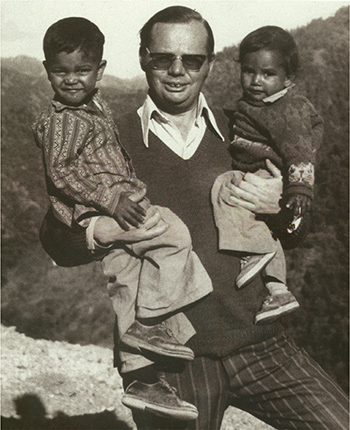

Mr H met me in Delhi at the station, which was very good of him. Time had indeed made us all better people—him more responsible than before, although I was being more reckless than I had ever been. Did my mother have something to do with him being there? She hadn’t followed the rules, after all, and maybe she understood me better at that time than others would have. Of course, it may just have been that Mr H happened to be in Delhi for some other work. Even so, he needn’t have come to receive me. So there he was, and we travelled together by train from Delhi to Dehradun.

As we approached Dehradun, the train entered a forest of familiar green. Every click of the rails brought me closer to all that I had missed and was now coming back to reclaim as my own. I belonged to the hot sunshine and muddy canals, the banyan trees and the mango groves, the smell of wet earth after summer rain, the relief of a monsoon thunderstorm, the laughing brown faces. And the intimacy of human contact—that was what I had missed the most in England. The orderly life, the good sense and civility were all admirable, but they did nothing for the soul. I missed the freedom to touch someone without being misunderstood; the freedom to hold someone’s hand as a mark of affection rather than desire, but also to show desire without reserve and find fulfilment. I missed being among strangers without feeling like an outsider; I missed everything that made it all right to be sentimental and emotional.

In Dehra, Somi’s cousin Dipi was at the station with his bicycle. I put my suitcase and travel bag in my stepfather’s second-hand car, pulled myself onto the crossbar of Dipi’s bicycle, and we rode through the streets of the town that had shaped my life, and brought me home.

I HAD LEFT LONDON FEELING A LITTLE DEPRESSED, BUT AS WE entered the Red Sea my spirits had soared with the temperature. At the end of the voyage, stepping off the gangway in Bombay, I was a happy young man, and happier all the way to Delhi and onwards to Dehra. The passage home had cost me about forty pounds, and I had a similar amount in cash with me. That would see me through the coming month, perhaps two, and that was as far as I dared to think.

Sometimes I feel my life has been a saga of new beginnings. Setbacks, failures, and then small successes to spur me on to other failures. In the beginning, I had to come to terms with the loss of my father, then create an identity for myself in my stepfather’s home. Off to Jersey to make a beginning of sorts in an atmosphere that was completely alien to me. Another beginning in London; small achievements amounting to nothing. And now back to India, and starting all over again.

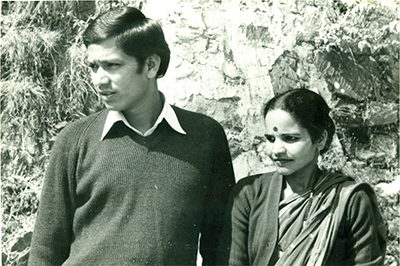

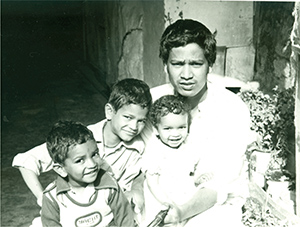

And what was I, anyway? English, like my father? Or Anglo-Indian, like my mother? Or Punjabi Indian, like my stepfather and half-brothers? Or a London Indian, like so many of my friends who had settled there, in body and in spirit?

Well, I was back in India, and I had no intention of going elsewhere, and as the land was full of all kinds of people of diverse origins, I decided I’d just be myself, all-Indian, even if it meant being a minority of one.

And ever the optimist, I was convinced that I could make a living from my writing, even though I could not see anyone else doing so.

I had my small typewriter, the one Mr Bromley had helped me purchase in Jersey, and I was soon putting it to good use. Although book publishers were in short supply, I was able to make a fairly impressive list of English-language magazines and newspapers to whom I could sell my wares, and it went something like this:

The Illustrated Weekly of India (first choice)

The Sunday Statesman (second choice)

Sport and Pastime

Sainik Samachar (armed forces weekly)

The Deccan Herald

The Tribune (Ambala)

Shankar’s Weekly

My Magazine of India (if it still exists)

Most of these publications included fiction in their supplements and magazines, so there was a ready market for my short stories. The Illustrated Weekly , I had found out, still paid Rs 50 for a story or article; Sainik Samachar , Rs 30; the others, Rs 25.

Before leaving London I had sold a story to the Young Elizabethan , a British literary magazine for older children, and I planned to send them more. And of course to the BBC, which paid fifteen guineas—fifteen pounds and fifteen shillings—for a fifteen-minute story. Back then, the rupee was stronger and the 180 or 190 rupees per story would keep me in some security, if not comfort, for a month.

Encouragement came from C.R. Mandy, the genial Irish editor of The Illustrated Weekly . He had published some of my early work, and now he accepted the first two stories I sent him. I would soon be bombarding him with almost everything I wrote.

But where was I to live?

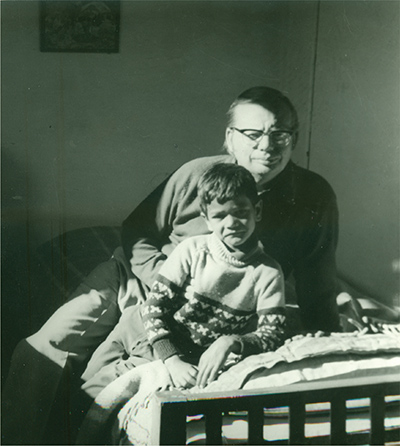

Though my mother and stepfather had welcomed me back, they were already packing to leave for Delhi. Mr H’s business dealings had gone awry yet again. He was now bankrupt; his workshop had closed down, he owed money to various people, and there were heavy demands from the income tax department. An old friend who ran a car business in New Delhi had offered him a job as a workshop manager, and he was glad (and wise) to accept it. As he and my mother were in financial difficulties, I could not expect much help from them; nor was I in a position to do much for them. They suggested that I accompany them to Delhi, but I hadn’t come back to live in Delhi. I wanted to stay on in Dehra, at least for the time-being. I wanted to be near old friends; I wanted new friends. I wanted the proximity of the hills and rivers. And above all, I wanted the freedom of being my very own person.

This was when Bibiji came into the picture.

Bibiji had a name of course, but everyone called her Bibiji. She was my stepfather’s first wife, the woman he had abandoned for my mother, and she became a guardian angel of sorts during those two and a half years in Dehra when I struggled to make a living as a freelance writer. If this sounds complicated, I suppose it was. It is the kind of thing that can only happen in India, or at least it was when I was twenty-one.

I got on rather well with this hardy, industrious lady, and sympathized with her predicament. In order to sustain herself and two small children after Mr H deserted her, she had started a kirana shop, a small provision store, in a corner of the Astley Hall shopping arcade, thus becoming Dehra’s first lady shopkeeper. She was a sturdy woman of balloon-like proportions, very strong in the arms, who could fling sacks of flour around as though they were shuttlecocks. On one occasion, early into Mr H’s affair with my mother, she had gone looking for them armed with an axe. I could see that she had probably been a little overwhelming for my diminutive stepfather.

Bibiji had rented a couple of rooms above the kirana shop and, as she lived alone, she offered to sublet one of these rooms to me for a nominal sum. I took it without hesitation, for it would have been impossible to find anything else in the centre of town that didn’t cost at least twice as much. Bibiji’s profits from the store were meagre, and she should really have been charging me more, but I think having me stay on her premises in Dehra, and not with my mother or stepfather in Delhi, gave her a victory of sorts.

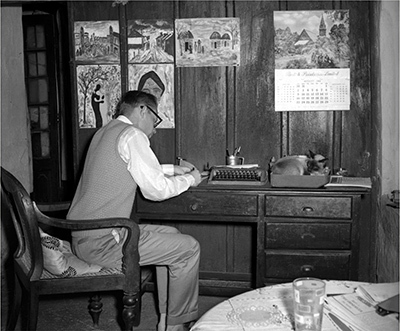

My room was bright and airy, with a balcony in front and a small veranda at the back. A neem tree grew in front of the building, and during the rains, when the neem-pods fell and were crushed underfoot, they gave off a rich, pungent odour which I can never forget. There were flats on either side of my room, served by a common stairway, which was blocked, at night, by a sleeping cow, over whom one had to climb, for it would move for no one. In the evenings I lit a kerosene lamp if I wanted to read or write, as there was no electricity—the bills having gone unpaid for several years. The amount due was now astronomical, and no one could afford to clear the arrears, so I had to manage without lights or a fan or a radio. Most of my writing was done in the mornings at my desk, especially during the hot summer months when I would fall asleep at mid-day.

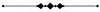

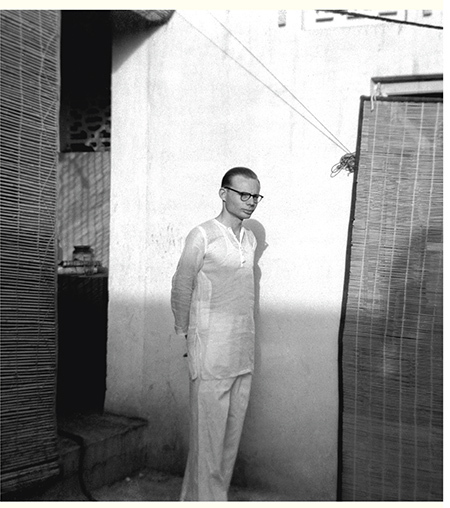

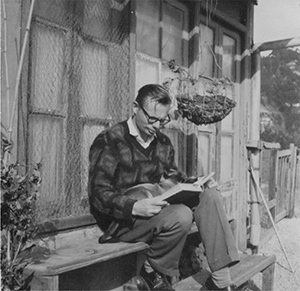

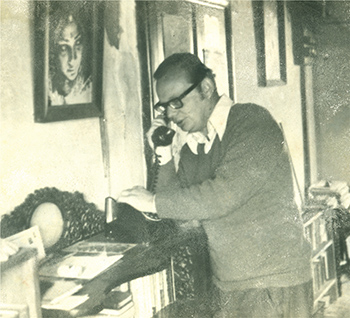

My ‘desk’ was a large dining table on which I spread out my notebooks, papers and typewriter. A couple of smooth rounded stones from the Rispana riverbed acted as paperweights. There was a framed photograph of my father and one of Vu Phuong. Daddy’s photograph is still on my desk. Vu’s moved from its frame into my album some months later, and there it has remained as a distant memory.

All my memories I examined, rearranged, edited, or sometimes just reproduced, for my stories. I was diligent about this, but I certainly did not burn the midnight oil in my striving to make a living as a writer. If I could manage one thousand words a day, I was satisfied. And this could be accomplished in a couple of hours. Afterwards, I would drop in at a café for a cup of coffee, and in the evenings I would walk to the bazaar for tikkis or kababs, and to look at strangers with whom I would imagine conducting intensely physical, clandestine affairs. Then I would return to light my kerosene lamp for an hour at night and jot down stray thoughts and ideas, or write a letter, before getting into bed alone.

I used to breakfast with Bibiji downstairs, behind the shop, where she had a small alcove to herself. Breakfast would consist of aaloo or mooli parathas (as many as I could consume) with a sabzi and pickles—all manner of pickles. I soon became a pickle aficionado, my favourites being shalgam (turnip), a very Punjabi pickle; or stuffed red chillies; or jackfruit pickle. It was very substantial fare and I usually didn’t need another meal till the evening, when I went down the road and took my dinner in a small restaurant or a dhaba. I was never any good as a cook, and these eating places were quite cheap—for five rupees I could have a decent non-vegetarian meal, and if I stuck to the basics—daal, rice and a vegetable—I could eat in three rupees.

During the day, Bibiji had no time to cook, as she had to run the shop, and that too without any help. I would come by and help her with bills and invoices and haphazard accounting. She was barely literate, but an astute shopkeeper; she knew instinctively who was good for credit and who was strictly nakad (cash), and she measured out quantities of rice, potatoes and lentils with the professionalism of any bazaar shopkeeper. I soon learnt the names of all the different, colourful daals that she displayed—moong, arhar, masoor, malka, etc (but alas, I can no longer tell one from the other). Her rajma (red beans) was in great demand, and people from Delhi would buy quantities of it. Dehra was also famous for its basmati rice, which was grown all over the Doon. Today, there are very few rice fields, the builders having taken over most of the countryside.

Once or twice a week, at the crack of dawn, Bibiji would set off for the wholesale market to procure her supplies. Normally, this was a bit too early for me to be up and about, but on a couple of occasions I made a special effort, got up and dressed and accompanied her to the wholesale market, in the depths of the Paltan Bazaar. This entailed a forty-minute march along deserted roads, then an hour of negotiating with vendors from the rural surroundings offering green peas or cabbage or cauliflowers, or mounds of rice, flour and daals, or onions and potatoes, all at fluctuating rates. Bibiji was of course good at bargaining, and hiring a push-cart, would soon have it loaded up with her purchases. Her favourite coolie, Mumtaz, would then trundle the cart back to Astley Hall and the provision store.

Who was Astley, and why was this shopping centre so named? Foreign road and place names have, over the years, come and gone, but Astley Hall is still (as I write) Astley Hall, just as Connaught Place in New Delhi remains Connaught Place. No one knows who Astley was; I don’t, either. Those who might have known are long ago gone. I can only speculate that Astley was a favourite son of one of the owners of the property on which this commercial centre came up, back in the early 1900s.

‘Astley’, of course, is often mispronounced, and Bibiji always called it ‘Asli’ Hall—‘asli’ meaning the ‘real thing’. Which was how she described my father, whom she had met just once, she said, when he had come to the old photo studio before Mr H sold it.

‘Your father was an asli Angrez (an Englishman),’ she would say, implying, I think, that he was a man of honour and good conduct. She didn’t have a good word for my mother, but that was understandable. When she referred to my father as a ‘Juntalman’, it was meant to be a judgement delivered about my mother and her—Bibiji’s—ex-husband.

Bibiji’s pronunciation was distinctly Punjabi. To her I was always ‘Rucksun’, not Ruskin.

‘Rucksun,’ she would say, ‘one day you must write my life story.’

And I would promise to do so.

Of the book that I had written, there was no news, and I had, in fact, forgotten all about it, being far too busy trying to sell my stories to magazines and make a living. I had made it my duty to study every English language publication that found its way to Dehra (most of them did), to see which of them published short fiction. A surprisingly large number of them did; the trouble was, the rates of payment were not very high, the average being about twenty-five rupees a story. Ten stories a month would therefore fetch me two hundred and fifty rupees—just enough for me to get by.

Only The Illustrated Weekly , as I have said, paid Rs 50 per story, and fortunately quite a few of my stories appeared in the paper. One day, a letter from C.R. Mandy informed me that he was going to serialize The Room on the Roof —and that was how I knew it had been published. Even Diana Athill had neglected to inform me. Copies of the book finally turned up, but I first saw it when serialization began in the Weekly , with lively illustrations by Mario Miranda, the Weekly’s well-known cartoonist and illustrator. That was in 1956, and I recall the morning well, because I wrote about it soon afterwards. I was twenty-two then and I am eighty-two now; a lot has happened since then, and if I sat down to make a list of all my mornings, I would probably remember more eventful ones. But as it was my first book, I suppose it deserves commemoration, so here’s the piece I wrote:

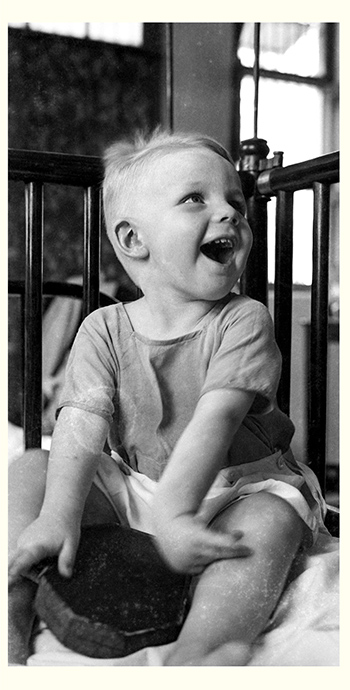

I was up a little earlier than usual, well before sunrise, well before my buxom landlady, Bibiji, called up to me to come down for my tea and parathas. It was going to be a special day and I wanted to tell the world about it. But when you’re twenty-one, the world isn’t really listening to you.

I bathed at the tap, put on a clean (but unpressed) shirt, trousers that needed cleaning, shoes that needed polishing. I never cared much about appearances. But I did have a nice leather belt with studs! I tightened it to the last notch. I was a slim boy, just a little undernourished.

On the streets, the milkmen on their bicycles were making their rounds, reminding me of William Saroyan, who sold newspapers as a boy, and recounted his experiences in The Bicycle Rider in Beverley Hills. Stray dogs and cows were nosing at dustbins. A truck loaded with bananas was slowly making its way towards the mandi. In the distance there was the whistle of an approaching train.

One or two small tea shops had just opened, and I stopped at one of them for a cup of tea. As it was a special day, I decided to treat myself to an omelette. The shopkeeper placed a record on his new electric record player, and the strains of a popular film tune served to wake up all the neighbours—a song about a girl’s red dupatta being blown away by a gust of wind and then retrieved by a handsome but unemployed youth. I finished my omelette and set off down the road to the bazaar.

It was a little too early for most of the shops to be open, but the news agency would be the first and that was where I was heading.

And there it was: the National News Agency, with piles of fresh newspapers piled up at the entrance. The Leader of Allahabad, the Pioneer of Lucknow, the Tribune of Ambala, and the bigger national dailies. But where was the latest Illustrated Weekly of IndiaWhat brings you here so early this morning?’What brings you here so early this morning?’What brings you here so early this morning?’? Was it late this week? I did not always get up at six in the morning to pick up the Weekly, but this week’s issue was a special one. It was my issue, my special bow to the readers of India and the whole wide beautiful wonderful world. My novel was to be published in England, but first it would be serialized in India!

Mr Gupta popped his head out of the half-open shop door and smiled at me.

‘What brings you here so early this morning?’

‘Has the Weekly arrived?’

‘Come in. It’s here. I can’t leave it on the pavement’.

I produced a rupee. ‘Give me two copies.’

‘Something special in it? Did you win first prize in the crossword competition?’

My hands were not exactly trembling as I opened the magazine, but my heart was in my mouth as I flipped through the pages of that revered journal—the one and only family magazine of the 1950s, the gateway to literary success—edited by a quirky Irishman, Shaun Mandy.

And there it was: the first instalment of The Room on the Roof, that naïve, youthful novel on which I had toiled for a couple of years. It had lively, evocative illustrations by Mario, who wasn’t much older than me. And a picture of the young author, looking gauche and gaunt and far from intellectual.

I waved the magazine in front of Mr Gupta. ‘My novel!’ I told him. ‘In this and the next five issues!’

He wasn’t too impressed. ‘Well, I hope circulation won’t drop,’ he laughed. ‘And you should have sent them a better photograph.’

Expansively, I bought a third copy.

‘Circulation is going up!’ said Mr Gupta.