Introduction

The destructive forces that lead to a mangled extremity can create complex fractures and strip and devitalize the soft tissue envelope. Salvaging the limb often requires osseous reconstruction and soft tissue coverage to provide an environment conducive to fracture healing while preserving or restoring function. Fortunately, there is a spectrum of soft tissue coverage options that vary in complexity and utility.

The “reconstructive ladder” describes tiers, or rungs, of increasingly complex soft tissue coverage options from local wound care, primary closure, skin graft, to local flaps, pedicled flaps, free flaps, or complex allotransplantation [1, 2]. The principle behind the ladder is to use the most simple, clinically appropriate option to provide soft tissue coverage while optimizing function, whether it is simple primary closure or complex microsurgical free flaps. The reconstructive ladder has been modified and revisited several times as technologic advances and new products such as negative pressure wound therapy and dermal matrices are applied to soft tissue management [2, 3].

There is some criticism to using the ladder concept dogmatically and strictly using the simplest technique for wound coverage in every case. Gottlieb coined the term “reconstructive elevator” to describe a more individualized treatment algorithm for a wound [4]. He argues that the surgeon should consider optimal form and function postoperatively for the wound rather than defaulting to the “simplest” technique. This may mean using a flap instead of a split-thickness skin graft to improve function. The hand in particular is an example of where wound coverage is only part of the goal, as mobility, function, sensation are equally important goals of treatment [5].

Whether climbing the “ladder” or taking the “elevator,” the treating team must take into account the anatomy of the injury, patient-specific personal factors, and the complexity of the procedure versus risk to the patient [6]. This chapter will focus on the non-microsurgical soft tissue coverage options such as local and regional flaps, fasciocutaneous, muscle, and myocutaneous flaps, which are powerful tools a non-microsurgical trained surgeon can use to provide coverage of a mangled extremity. The lower tiers of wound coverage options such as skin and skin substitute products will not be covered in this chapter, nor will the higher tiers of microsurgical options that require specialized training. The techniques described below are considered “workhorse” flaps for upper and lower extremity coverage, but there are several other options that are beyond the scope of this chapter.

Indications

Non-microsurgical soft tissue coverage techniques are useful for wounds that need more than a split-thickness skin graft, but may not necessarily need a free flap. These techniques are generally indicated for wounds that are unable to close primarily, as well as wounds unlikely to heal by secondary intention. Primary or delayed primary closure works well for clean, easily approximated wound edges that are not under much tension. In the mangled extremity, this scenario is rare as most wounds require multiple procedures to debride and resect devitalized tissue, and the swelling that has occurred by the time of closure usually precludes tension-free closure. Healing by secondary intention is also not an ideal option when tendons, vessels, and/or nerves are exposed. Unfortunately, mangled extremities are subject to wound breakdown leading to exposed internal fixation implants, vasculature, or tendons, which would also be an indication for local or rotational flap coverage.

Patients with mangled extremities are often polytrauma victims that have other injuries that do not allow for a prolonged operative procedure, and in some cases, they may lack healthy donor sites to provide free-flap coverage. In this scenario, non-microsurgical soft tissue coverage can be used to provide a protective environment for large defects or exposed tendons or neurovascular structures to promote healing and reduce the risk of continued infection while sparing the patient from a physiologically demanding and extensive procedure.

Preoperative Workup

A thorough history to obtain the mechanism, timing, and location of injuries is important for appropriately managing a mangled extremity. For example, if the patient is a polytrauma patient requiring other life-saving procedures, communication with the trauma team is important to discuss timing and tolerance of limb surgery [11]. The degree of contamination and mechanism of injury help anticipate the likelihood of salvage versus amputation, as well as provide clues as to how much healthy soft tissue will be available after multiple debridements. The patient’s nutrition, smoking, and psychological status are also important factors to consider when planning soft tissue coverage. For example, patients who are poor hosts due to smoking or malnutrition may not be the best candidates for flaps, and psychiatric conditions or social barriers to adequate participation with postoperative restrictions or wound care will impact inpatient as well as outpatient disposition [6]. Physical exam findings with regard to vascular and neurologic status, degree of soft tissue damage, and bone or joint exposure will help dictate type of coverage needed as well as what soft tissue will be available.

Initial radiographs to determine bony injuries should be obtained. Advanced diagnostic imaging studies such as angiography, CT angiography, or ultrasound are useful if the vessels to the planned soft tissue coverage are in question, but these studies are usually optional.

Several objective measures have been described to predict outcomes of attempted limb salvage versus amputation. For example, the Mangled Extremity Severity Score (MESS) was described by Johansen et al. in 1990 to rate lower extremity trauma based on measures of skeletal or soft tissue injury, limb ischemia, shock, and age [12]. They set a cutoff score of 7 as predictive of amputation. However, later studies including LEAP (Lower Extremity Assessment Project) study group data and PROOVIT (PROspective Observational Vascular Injury Treatment) registry data were unable to establish a predictive value of MESS for functional status nor need for amputation [13, 14]. While objective scoring systems are helpful to generally categorize injury severity, the ultimate decision to attempt limb salvage versus amputation should be a team approach that incorporates the input from orthopedic, plastic, and trauma surgical teams as well as patient factors. As the time for operative management of the mangled extremity approaches, backup plans for coverage should be discussed beforehand with all teams, so that the necessary equipment and staff are available.

Wound, Patient, and Timing Considerations

When managing a wound that requires soft tissue coverage, the treating surgeon should consider several factors to decide on the appropriate coverage method and timing. Elevating rotational skin and muscle flaps requires available, non-traumatized local donor options. Ideally, this would be supple, non-edematous tissue in the desired area of flap elevation. Adequate debridement and the treatment of any preexisting infection are mandatory prior to flap coverage. In some situations, the wound dimensions or location may preclude local coverage options. These wounds may be better suited to distant free tissue transfer options.

Patients with significant comorbid conditions who are poor candidates for limb salvage could be a contraindication to soft tissue reconstruction. Furthermore, the patient’s financial, social, and emotional circumstances should be taken into consideration when determining coverage options [6]. In a scenario where the patient’s injury or their ability to be a good steward of their wounds are compromised, the surgeon should pause and consider other options before moving forward with using complex techniques requiring significant resources.

With regard to the timing of soft tissue coverage, factors such as amount of contamination, amount of swelling, and availability of a microsurgical team are all part of determining when to cover a wound. Repeating debridements until a wound was culture negative before definitive coverage in open tibia fractures was shown to have low rates of deep infection [7]. Even with institution of an ortho-specific microsurgery team, coverage of open fractures can be delayed by several days, although no statistically significant difference was seen between early (<7 days) and late coverage [8]. Delaying coverage and elevating the traumatized limb until swelling is reduced and tissue equilibrium is achieved decreases the technical difficulty of dissecting tissue planes and also reduces vessel friability. A German study showed a low rate of flap complications in retrospectively reviewed cases of delayed (>3 days) soft tissue reconstruction of open extremity fractures [9]. However, there is also opinion that exposed structures, especially in the upper extremity, should be covered as soon as possible, or less than 72 hours, if feasible [10].

Non-microsurgical Soft Tissue Coverage Options

Local Flaps

Local skin flaps provide subcutaneous fat and skin coverage of wound defects. This option can provide sensate tissue over the wound, but local flaps depend on available nearby lax soft tissue. If the local manipulation of skin and fat causes too much tension, it may necessitate skin grafting the donor site. Options such as Z-plasty or rhomboid (Limberg) flap are commonly used methods to cover small wounds [15, 16]. In general, mangled extremities have defects too large to be adequately covered using these methods, but if the wound is appropriate, local, random pattern transposition flaps are straightforward and useful coverage options.

Non-healing over antecubital fossa covered with local flap intraoperatively and at 2-week follow-up

Fascial and Fasciocutaneous

Local skin flaps with underlying fascia attached are helpful in staged reconstructions. Compared to myocutaneous flaps, they are less scarred and fibrotic when they heal, providing functional and cosmetic benefits. Theoretically, decreased scarring allows structures such as tendons and neurovascular structures to glide underneath the flap. These flaps also tend to have better cosmetic outcomes than myocutaneous flaps due to their decreased relative bulk if they are transferred as fascia-only flaps. Wound healing is thought to be promoted by restoration of venous and lymphatic circulation.

Radial Forearm

The radial forearm flap is a versatile option for covering defects of the distal upper extremity given that it can be used both as a free and pedicled flap. It is a radial artery-based flap with sensation provided through the medial and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves. It can be used as an antegrade or reversed flow flap depending on the location of the defect to be covered.

Preoperatively, an Allen test is mandatory to assess for any pathologic results to avoid ischemia to the hand. The radial artery course is marked out and the amount of coverage needed is templated out, centered over the radial artery. This should be planned with consideration of the axis around which the flap will pivot.

The flap should be harvested from distal and ulnar to proximal and radial. The dissection can be carried out in either a sub- or supra-fascial manner, depending on the need. During dissection, the paratenon of the flexor carpi radialis tendon should be preserved. Once the intermuscular septum is encountered, perforators to the bone are carefully taken down, while perforators to the skin are preserved. The artery should be separated from the surrounding tissue until the flap is free enough to either rotate or tunnel. The donor site can be closed primarily if the defect is small; however, this site often requires a separate full- or split-thickness skin graft [17].

Lateral Arm Flap

The lateral arm flap is taken from the lower lateral aspect of the arm above the epicondyle. This flap is based on the posterior radial collateral artery with sensation from the lateral brachial cutaneous nerve and can provide a fairly substantial amount of tissue when elevated as an extended flap [18–20]. The extended lateral arm flap is useful as an axial transposition flap for posterior elbow and olecranon wound coverage [21].

The desired flap is outlined, the anterior incision is made first, the fascia of the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles is elevated, and the radial nerve is identified in the interval and can be protected. The posterior incision can then be made, elevating triceps fascia, and the flap is then elevated from a distal to proximal direction, essentially subperiosteally off of the lateral humeral ridge in order to include the pedicle that runs with the lateral intermuscular septum. There are several perforators within the septum that are preserved by elevating in this manner, ensuring perfusion of the skin island. Once the flap is raised, it can be rotated, or tunneled as an island flap [22].

Lateral arm flap used to cover exposed hardware as well as the bony prominence of the olecranon

Groin Flap

The groin flap is a technique described in 1972 by McGregor and Jackson to provide coverage of upper extremity traumatic soft tissue defects [23]. This flap is based on the superficial circumflex artery and provides a large surface area to work with. The flap is raised starting from lateral to medial including the fascia lata medial to the anterior superior iliac spine terminating at the medial border of the sartorius muscle [24]. When planning the outline of the flap, an additional 2–3 cm can be added to the length for some mobility [25]. Once the flap is mobilized, coverage is obtained, and the unused portion is tubed. Although this method provides reliable soft tissue coverage, patients treated with this technique are subjected to a period of bed rest, and the grafted limb is immobilized until the second stage of detachment. In a polytrauma patient that remains intubated or sedated, this may not be of much consequence. However, the patient with an isolated mangled extremity may experience some discomfort with their positional and activity restrictions.

Ballistic injury to hand requiring internal fixation and soft tissue coverage with a groin flap acutely. (Pictures courtesy of Raymond Pensy, MD)

Propeller Flap

The pedicled propeller flap can be useful in the lower extremity, especially in the distal third of the limb where the thin soft tissue envelope can leave bone, tendon, and neurovascular structures exposed after trauma [26]. Proximally, there is a thicker soft tissue envelope, and perforator vessels arise from the posterior tibial artery, anterior tibial artery, and the peroneal artery. Flaps can be raised from any of these vessels, and a single perforator can perfuse a fairly large surface area [27].

Perforator arteries are first detected using a handheld ultrasound Doppler and marked out. The outline of the flap is then planned to provide adequate length and coverage. Subfascial dissection is carried out to directly visualize the perforator vessel around which the flap will rotate. The perforator branch is then isolated and dissected free to allow for appropriate rotation. Once the flap is mobilized to cover the defect, perfusion is carefully checked and verified before the flap is closed over drains [26–28].

Exposed hardware and soft tissue defect in distal lower extremity requiring a propeller flap with demonstration of rotation of the flap. (Pictures courtesy of Raymond Pensy, MD)

Reverse Sural Artery Pedicle Flap

Reverse sural artery pedicle flap is a peroneal artery-based flap that can be used for fasciocutaneous coverage of the lower leg and foot. It is a useful flap due to its reliable blood supply that does not need to be sacrificed, as well as its fairly straightforward dissection with generally low blood loss. It is extremely useful for distal lower extremity coverage with demonstrated success in blast victims [29]. It does have a reputation for high rate of venous congestion, but a wide pedicle width can enhance venous drainage and reduce this risk [30].

The patient is placed in a prone or lateral decubitus position. After the flap is traced out, the incision is made distal to proximal. The sural nerve and the short saphenous vein should be kept together and preserved with the flap. Perforators are identified 5–10 cm proximal to the tip of the lateral malleolus. The sural nerve can be transected and ligated proximally to mobilize the flap. The flap should be attached with minimal tension with anchoring sutures. The donor sites may be able to be closed primarily depending on the size, but some may require split-thickness skin grafts [29, 31].

Posterior lower leg wound breakdown with exposed tendon treated with reverse sural artery flap and split-thickness skin graft that went on to subsequent healing. (Pictures courtesy of Sam Fuller, MD)

Muscular and Myocutaneous

Myocutaneous or pedicled muscular flaps can be used in cases of underlying osteomyelitis, areas where there are large defects from debridement, or in wounds that were grossly contaminated. The increased bulk of muscle flaps may be cosmetically displeasing in areas with previously thin soft tissue coverage; however, in regions with deeper, larger defects, the increased bulk of the flap can help fill these spaces in. These flaps do incur a fairly large donor site morbidity and may result in compromised function in the donor region.

Flexor Carpi Ulnaris (FCU) Flap

The FCU flap is a useful and reliable option for posterior elbow coverage where lack of muscle and other subcutaneous tissue predisposes this area to coverage issues [32]. The FCU muscle belly receives its blood supply from the ulnar artery and the posterior ulnar recurrent artery, with ulnar nerve innervation. The flap provides approximately 4 cm of coverage [32–34]. The FCU is also bipennate, which can reduce donor morbidity if it is split rather than taken in whole, although this is rarely indicated in our practice. This muscle can also be harvested as a myocutaneous flap with an overlying skin paddle centered over the muscle belly at the junction between the distal two thirds of the forearm. The dominant perforators enter the muscle at this level and do not need to be visualized or specifically isolated.

The flap is raised from distal to proximal along the posterior ulnar border from the pisiform. The FCU muscle is then elevated similarly from distal to proximal with ligation of minor perforators. The dominant pedicle enters approximately 6 cm distal from the olecranon tip and should be isolated with careful dissection to allow for mobilization. Flap stabilization and wound closure should be done with the elbow at 90° to assess the tension on the flap with elbow flexion [33].

Wound dehiscence with FCU flap planned, raised, and tunneled to the defect with primary closure of the donor site. (Pictures courtesy of Ebrahim Paryavi, MD)

Gastrocnemius Flap

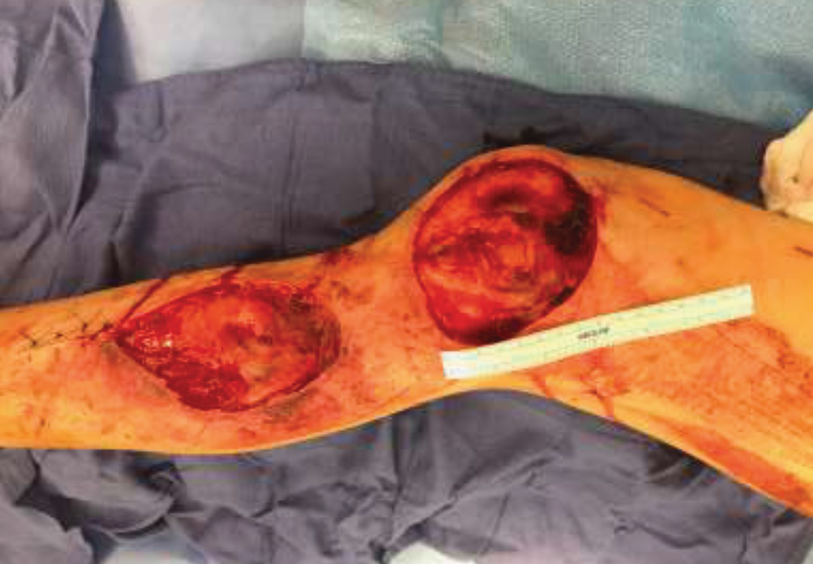

A 25-year-old male with significant road rash and soft tissue defects after motorcycle accident, amenable to a lateral gastrocnemius flap. (Picture courtesy of Ebrahim Paryavi, MD)

For a medial gastrocnemius flap, the incision is made on the medial aspect of the leg from the medial tibia posterior to the pes anserine tendons proximally to about 10 cm above the ankle [35]. The superficial posterior compartment fascia is released, and the medial gastrocnemius is isolated from the lateral head and from the soleus. The muscle is transected distally. Dissection can then proceed proximally to free the attachment to the medial femoral condyle. The muscle flap can then be tunneled or rotated over to cover the defect. The skin is closed over drains. The defect covered by the gastrocnemius will require a split-thickness skin graft or synthetic equivalent.

The lateral gastrocnemius flap is harvested with an incision on the lateral aspect of the leg about 2 cm posterior to the fibular head and parallel with the shaft [35]. Neurovascular structures are carefully dissected, and the small saphenous vein and sural nerve can be used to identify the median raphe [36]. The muscle belly should be bluntly dissected as in the medial flap away from the soleus and transected distally once freed. The flap can be tunneled and rotated as needed.

Latissimus Dorsi Flap

The latissimus dorsi flap is a pedicled muscular or myocutaneous flap that can provide a large area of soft tissue coverage for the upper extremity. Its primary blood supply is the thoracodorsal artery, but it also has secondary blood supply from perforators [37]. The muscle is innervated by the thoracodorsal nerve, and if necessary, the flap can be used as a functional muscle tendon transfer. If soft tissue coverage is the only need, the muscle can be denervated to allow for atrophy and less bulk.

Graft harvest is done with the patient in the lateral decubitus position with a wide area prepped out. If the flap is to be used as a myocutaneous flap, this should be incorporated into the planned incision. The flap should be raised from distal to proximal to approach the pedicle, which should be 10–12 cm from the axilla [37]. The pedicle is isolated, and the muscle is elevated before tunneling or rotating to the defect.

(a) Clinical photograph on presentation demonstrating significant contamination and devitalized tissue. (b) 3D CT reconstruction. (c, d) Debridement followed by fixation (same day). Debridement was completed followed by re-prep, re-drape, new back table and fresh instruments, and new gowns for all operative staff prior to fixation at same setting. (e) Pedicled latissimus flap POD#1 to achieve soft tissue coverage, anchoring latissimus to scapula and remnants of supra- and infraspinatus tendons for additional abduction/external rotation strength. (f, g) Final follow-up clinical photos. (a–g Courtesy of Raymond Pensy, MD)

Conclusion

Each mangled extremity case will provide unique challenges and opportunities for management. There is no one-technique or one-flap-fits-all when managing open wounds. The condition of the wound as well as the condition of the patient will help guide coverage options. In situations where primary closure or microsurgical techniques are not possible, there are several flap options that do not require microsurgical training. When used appropriately, these non-microsurgical flaps are valuable tools for any surgeon that manages mangled extremities. However, they should be planned out carefully and used appropriately to achieve the goal of reliable coverage and optimal function postoperatively.