Photo Section

Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

“GREAT” BEFORE GREAT. After World War II, the federal government launched a giant program subsidizing home purchases, largely in the suburbs, for working-and middle-class Americans. For the poor, Washington created urban renewal, a costly undertaking that included vast housing projects of rental apartments. Small businesses and families in the bulldozers’ path protested. “Urban renewal . . . means negro removal, and the federal government is accomplice to this fact,” concluded the writer James Baldwin. The Supreme Court backed the bulldozers, and complexes such as Pruitt-Igoe of St. Louis (below) replaced much-loved neighborhoods. As the 1960s dawned, federal planners confidently predicted that a growing economy and even more ambitious spending would ensure unqualified success for projects like Pruitt-Igoe and their inhabitants.

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

Associated Press

PLANNERS AND THEIR BONANZA. Most politicians and experts believed that when three groups—the government, big business, and unions—sat at one table, optimal growth for the country resulted. Economists counseled that a “mixed economy”—part public, part private, and heavily coordinated—suited the nation best. Above, President John F. Kennedy hosts Henry Ford II, Joseph Block of Inland Steel, Thomas Watson of IBM, George Meany of the AFL-CIO, Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers, and future Federal Reserve chairman Arthur Burns, among others. What Americans should do with wealth once they had it was the topic of a TV Western that debuted as the 1960s commenced, Bonanza.

Getty Images/NBC/Contributor

Getty Images/Corbis Historical

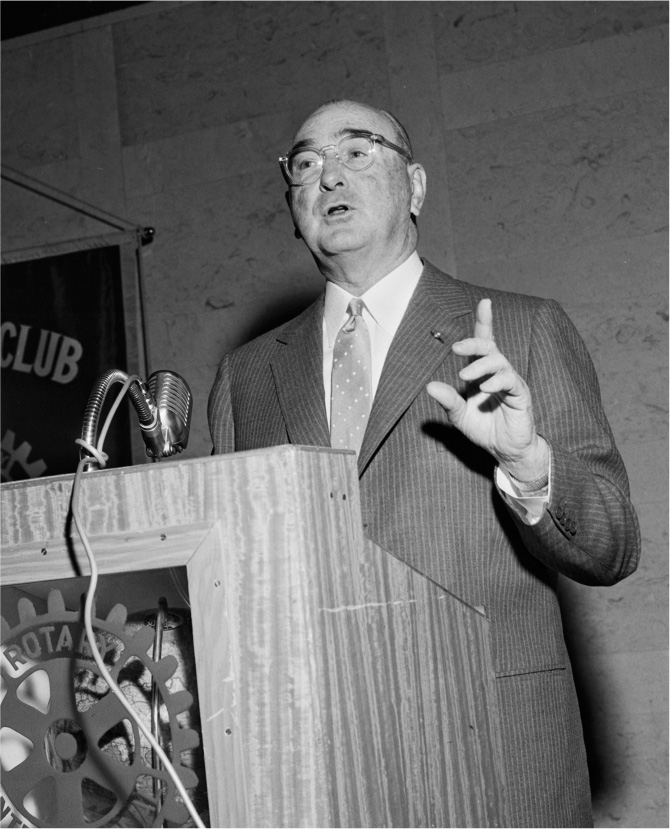

THE THREAT TO THE BONANZA. One man believed that top-down coordination actually threatened growth, and that America could slide into populism or dictatorship. Lemuel Boulware (above), an executive at GE, argued that seemingly benign social institutions, such as labor unions, put America on the wrong path.

Associated Press/Getty Images/University of Southern California/Contributor

Boulware hired an aging actor, Ronald Reagan, to make the case for purer capitalism. (Above, Reagan plays a Soviet colonel on GE Theater.) A philosopher who also warned of the dangers of the “mixed economy,” Friedrich von Hayek (below), suggested America risked stepping onto the “road to serfdom.” For many, such fearmongering seemed outdated and extreme.

Getty Images/Paul Popper/Popperfoto/Contributor

Getty Images, Michael Ochs

IT STARTED AT PORT HURON. In June 1962, a number of young Americans gathered at cabins outside Port Huron, Michigan, to forge their own plans to transform society and to build up new institutions, including the Students for a Democratic Society. Michael Harrington (above), a socialist, argued for partnership with the established Democratic Party.

Getty Images/Robert Elfstrom/Villion Films/Contributor

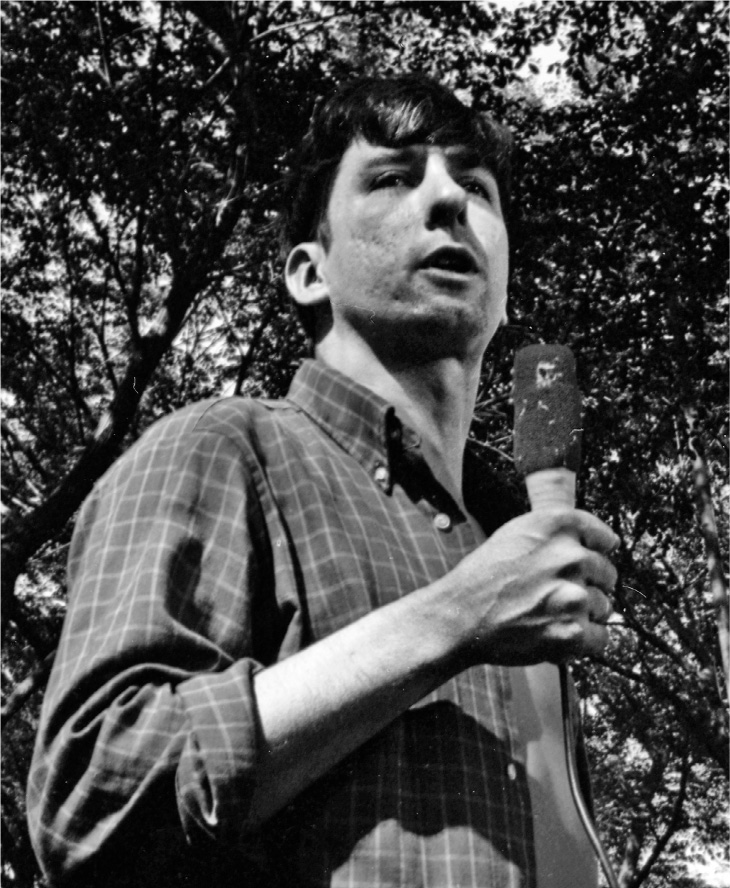

Robert Parris Moses (above), a math instructor who became a civil rights leader, led dangerous voter registration drives in the segregated South.

Getty Images/Frew W. McDarrah/Contributor

Tom and Casey Hayden (above and below) pushed for new protests and community action to win jobs and dignity for workers.

Courtesy of Casey Hayden

Getty Images/William C. Shrout/Contributor

THE UNIONS IN THE BACKGROUND. Though the student activism of the early 1960s appeared spontaneous, it was not entirely so. Union groups, including Walter Reuther’s (above) United Auto Workers and the AFL-CIO, funded the Port Huron activists.

Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

Reuther’s UAW aide, Mildred Jeffrey (above right, with Lady Bird Johnson), actually arranged the stay at the Port Huron cabins for the students. Reuther believed that engaging a youth wing would help unions lead the entire country away from bigotry and toward his ideal, Western European social democracy. Reuther was also an early supporter of Martin Luther King Jr. When King and other demonstrators landed in a Birmingham jail, Reuther sent UAW executives with $160,000 in cash strapped to their belts to bail them out.

Associated Press

Getty Images/Grey Villet/Contributor

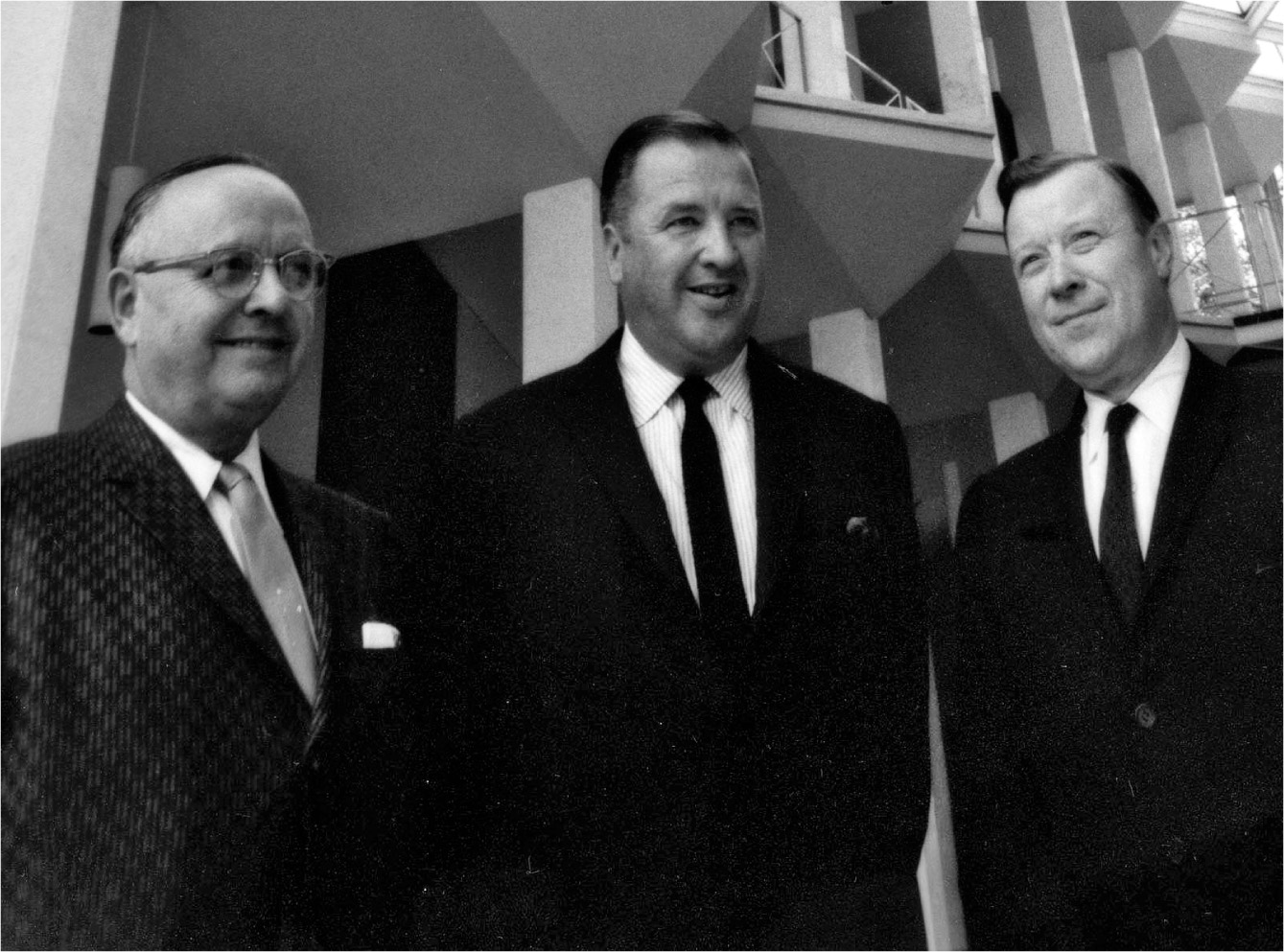

THE BEST AND THE BRIGHTEST. The automakers who employed Reuther’s workers operated from the top down. George Romney of American Motors (above) was among several successful executives, including Robert McNamara of Ford, who believed their mastery of business would translate to mastery in government. Throughout the 1960s, Detroit’s mayors, automakers, and union leaders (below from left, Detroit mayor Louis Miriani, Henry Ford II, and Reuther) did follow the lead of European social democrats, agreeing on unprecedented wages and benefits for workers. Few asked whether the generous pay packets would render Detroit uncompetitive.

Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

Courtesy of NASA

MANKIND—OR MAN? In the early 1960s, government offered one model of how to “get to great”—collective projects. The most inspiring of such projects was Kennedy’s “Man to the Moon” space program, which distracted the country from its own troubles: errors in Vietnam and riots in the cities. In the same period, however, business startups were beginning to demonstrate the potential of the individual to move the country forward. Below, the “Traitorous Eight”: Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and six others who left Shockley Semiconductor in 1957 to found Fairchild Semiconductor. Fairchild in turn begat Intel—and an entire new culture of enterprise.

Wayne Miller/Magnum Photo

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

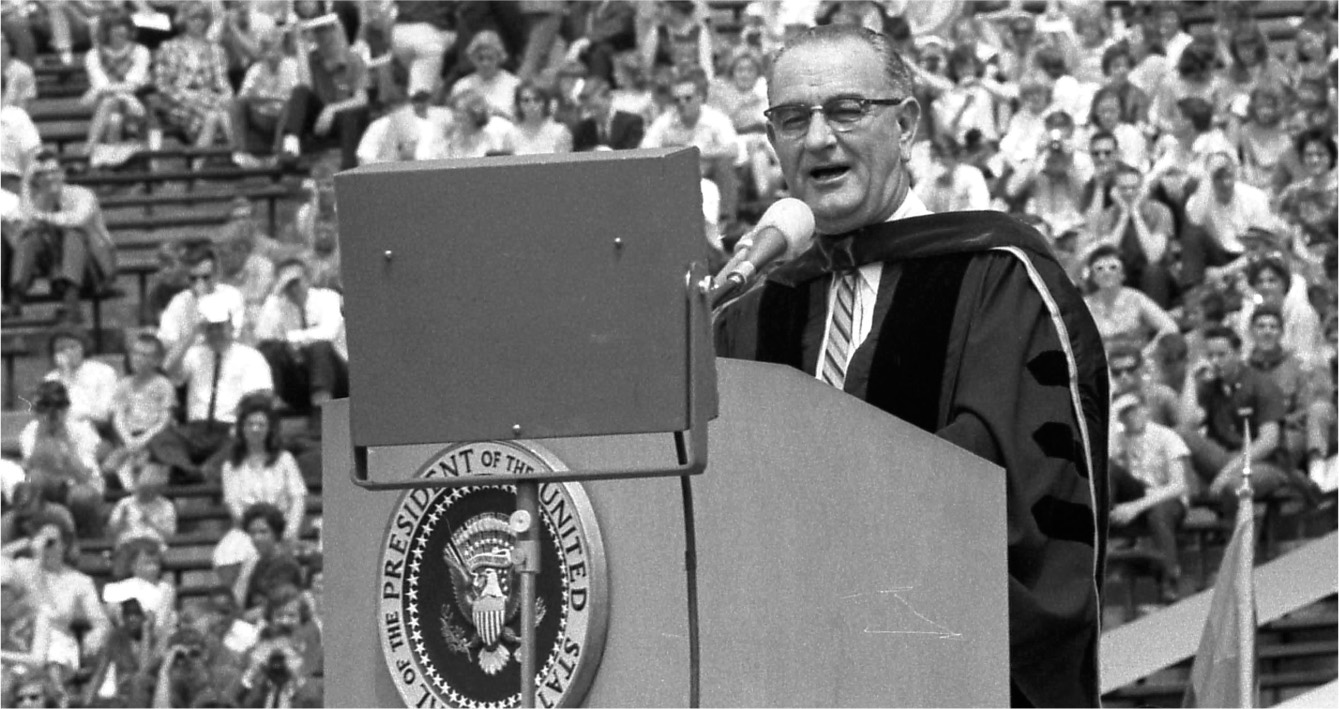

THE GREAT SOCIETY BECOMES OFFICIAL. As a U.S. congressman and senator, Lyndon Johnson had lionized both New Deal father Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman. On becoming president, Johnson sought to implement a program that expanded on his predecessors’ progressive legacy. At the University of Michigan in 1964, Johnson made the Great Society official, declaring he would cure poverty. “Our aim is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it, and above all to prevent it,” the president said. With the Michigan speech, Johnson made the portentous choice for the entire nation: America would attempt advancement through the public sector. To the private sector, Johnson assigned the job of funding the undertaking.

BL012296, University of Michigan News and Information Services Photographs, Bentley Historical

Getty Images/Historical/Contributor

BENZEDRINE IN THE AIR-CONDITIONING. Sargent Shriver, President Kennedy’s brother-in-law, directed the Peace Corps. Johnson tapped the energetic Shriver to lead the War on Poverty as well. If church charity helped the poor, Shriver reasoned, so should government spending. Shriver’s Office of Economic Opportunity commenced multiple controversial programs.

Associated Press

Getty Images/Fred W. McDarrah/Contributor

STUDENTS TRY TO CHANGE THE CITIES. Inspired by the unions and the federal government’s War on Poverty, many young activists headed to northern cities, where they hoped to help the poor find a voice. Tom Hayden created the National Community Union Project for Newark, but NCUP had trouble finding a constituency.

Getty Images/New York Daily News Archive/Contributor

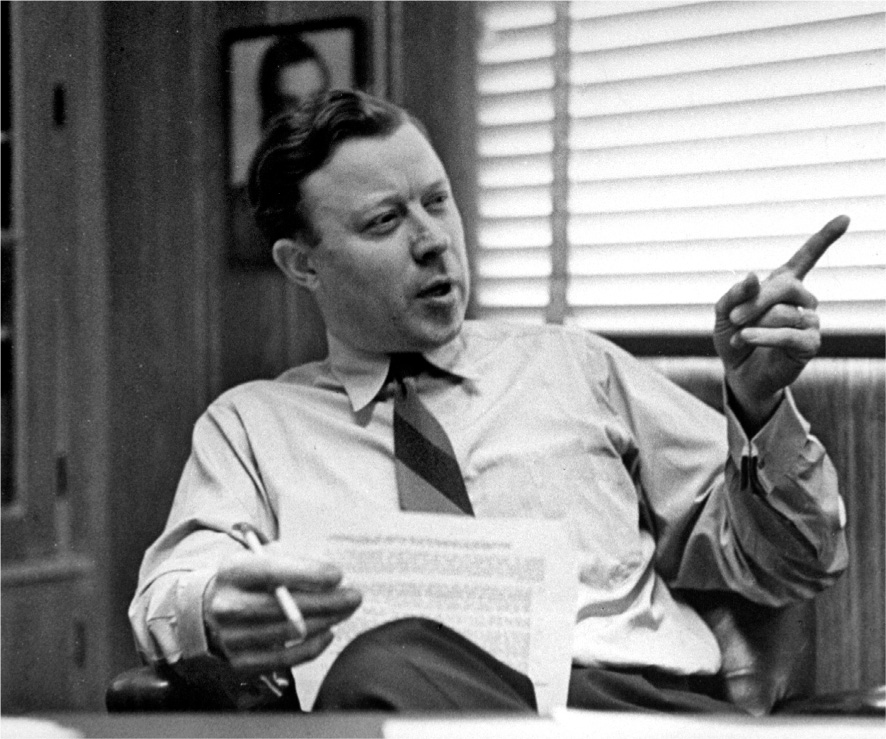

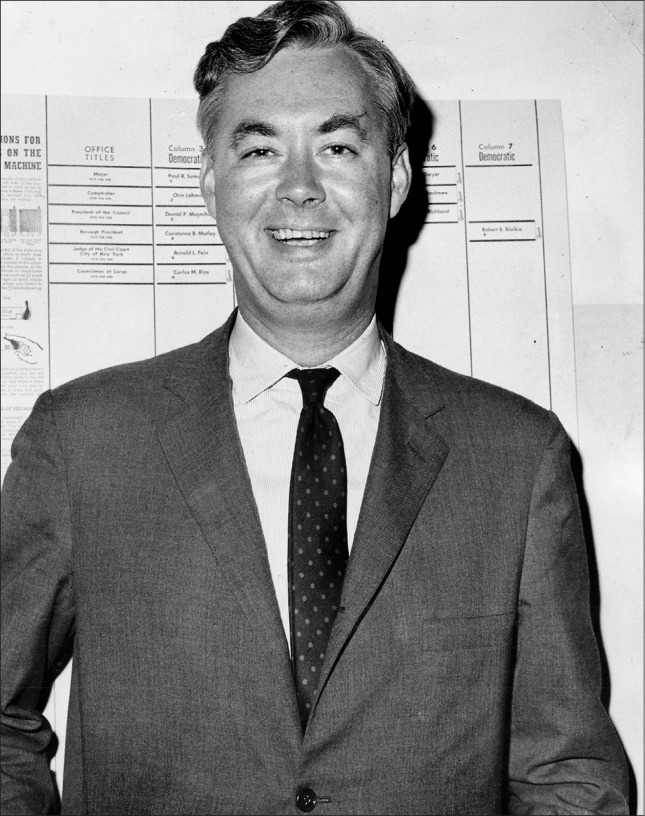

THE IDEA MAN. Daniel Patrick “Pat” Moynihan helped craft John F. Kennedy’s Executive Order 10988, which gave federal workers’ unions the authority to bargain collectively on workers’ behalf. Few thought the change meant much, but 10988 set the stage for a new kind of labor powerhouse—public sector unions.

Associated Press

PLANNING SOME MORE. President Johnson placed faith in young experts. As Kennedy had turned to whiz kids to manage foreign policy, so Johnson assigned them to the Great Society as well. Here poverty czar Shriver hands out cigars to celebrate the birth of his fourth child; Secretary McNamara sits to Shriver’s left.

Associated Press

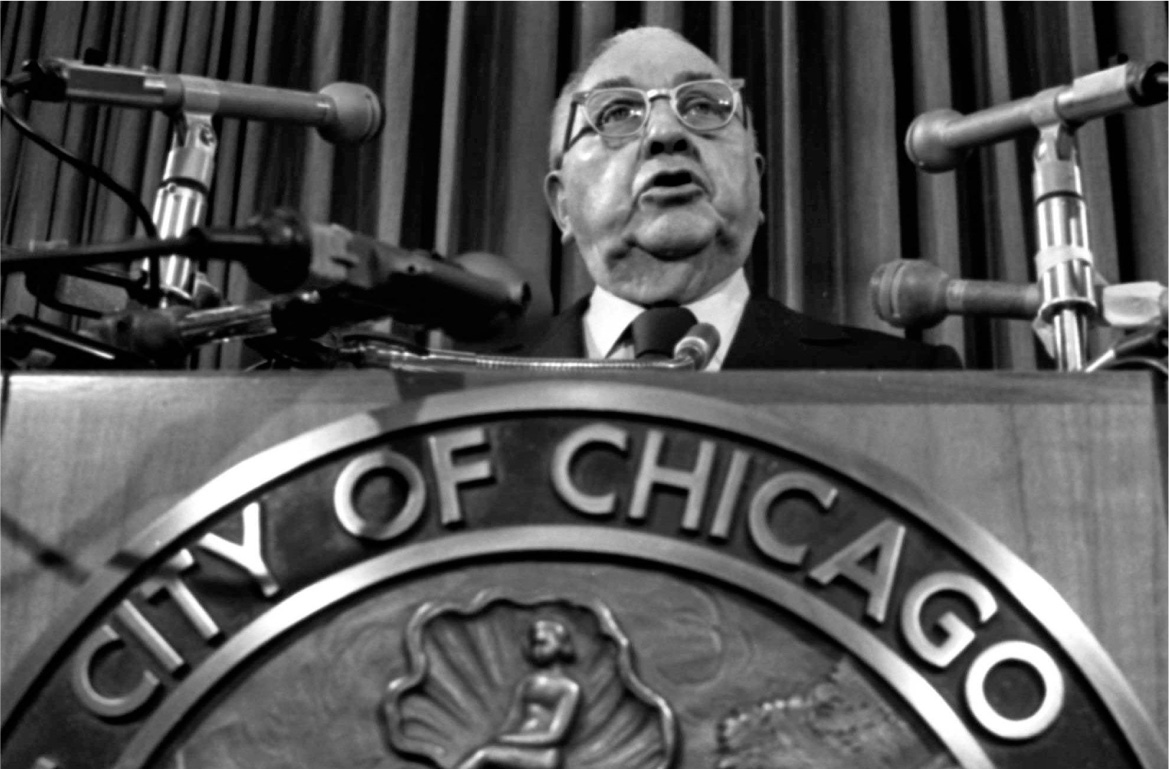

THE MAYORS STRIKE BACK. In a landmark 1965 speech at Howard University, President Johnson shifted the Great Society’s emphasis from equality of opportunity to equality of result. “Freedom is not enough,” Johnson said. The nation’s mayors first welcomed the flow of help and cash that the Great Society represented, assuming that the funds available would go into their own poverty or community programs. Soon enough, however, the mayors started to resent the intrusion of the federal government, especially when Washington funded social activists to challenge the mayors politically. Two of Johnson’s fellow Democrats resisted the federal usurper: Sam Yorty of Los Angeles (above) and Richard J. Daley of Chicago (below), an old ally of President Johnson’s.

Associated Press

Associated Press

TENSION FROM THE BEGINNING. “Guns and butter” was how Johnson’s dual commitment to spending on Vietnam and the Great Society was described. The “butter” part included two expansive health care programs—Medicare for seniors and Medicaid for the poor. But could the country actually afford both guns and butter? Federal Reserve chairman William McChesney Martin (above, with Johnson) feared not, believing overspending would challenge not only budgets but the U.S. currency. Governments of other nations shared the Fed chair’s concern about the future of the dollar. French leader Charles de Gaulle (below) was among them. “The world needs an indisputable monetary base that bears the mark of no country in particular,” de Gaulle said.

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

Getty Images/LE TELLIER Philippe/Contributor

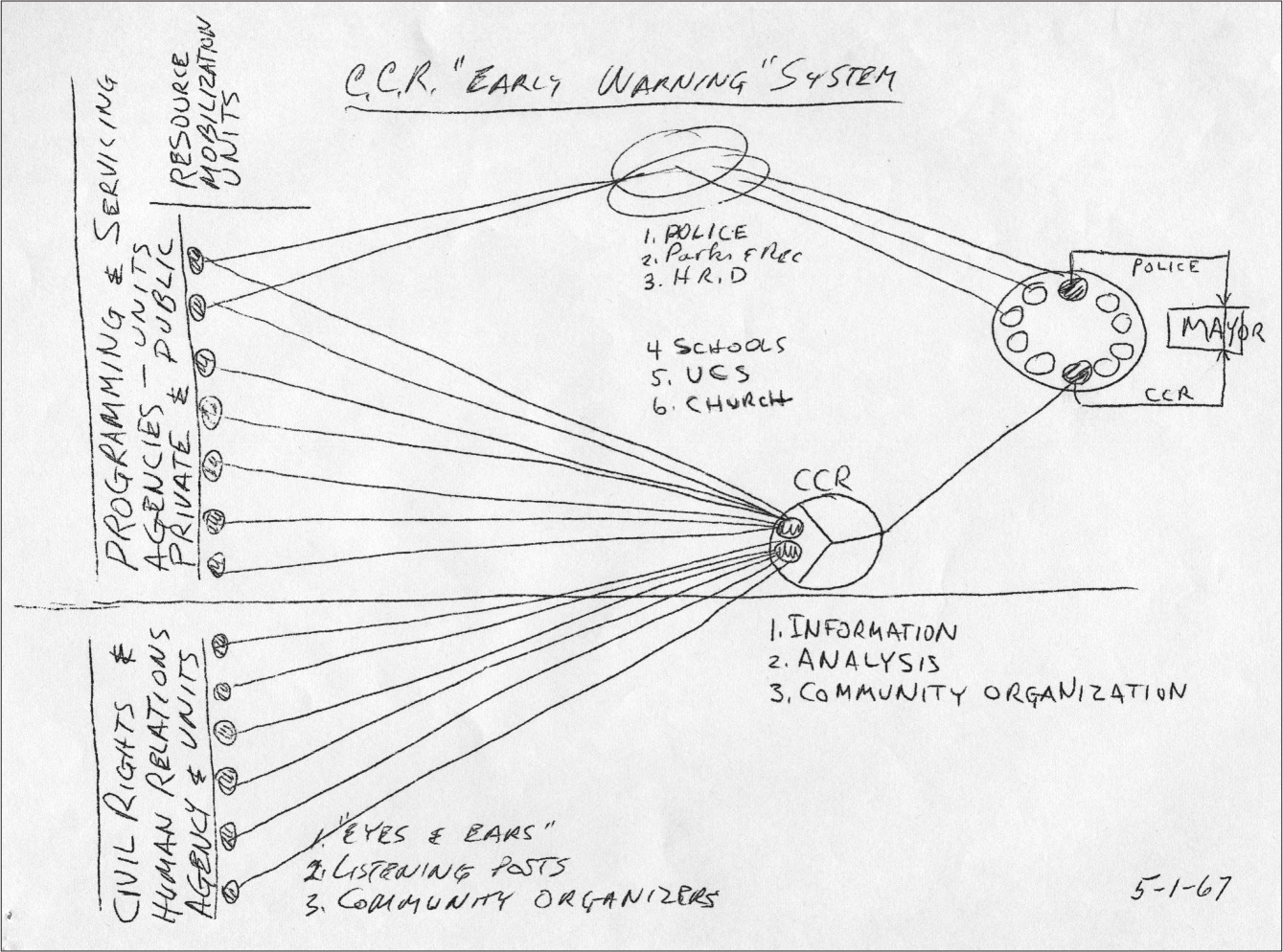

A METAL THAT REFLECTED DISTRUST, AND A COUNTRY THAT NO LONGER TRUSTED ITS PEOPLE. Like Bitcoin today, gold in its day was the measure of the world’s distrust of the U.S. dollar. The infatuation with the commodity spread to the popular culture. Pictured above is the Paris opening of Goldfinger, about a plot to take over the world’s gold supply by irradiating Fort Knox. At home, federal, state, and city authorities felt increasingly estranged from their constituents. Below is an elaborate riot repsonse crisis protocol readied by Detroit police.

Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

Associated Press

THE FIRE THIS TIME. The experts notwithstanding, 1960s reforms made as little progress as earlier federal efforts. Still isolated, poor and working-class families found too little of the bonanza was reaching them. The wonder world they viewed in the shows on their new television sets only deepened their disillusionment. Detroit’s elaborate riot prevention plan was never implemented—riots erupted too quickly. The August 1965 Watts riot in Sam Yorty’s Los Angeles (above) left thirty-four dead, a thousand injured, and millions of dollars in property damage across days of violence.

US National Archive/HUD Staff

GREAT SOCIETY II. Frustrated that civil rights laws and new entitlements were not reducing American discontent, President Johnson turned to housing. The massive scale of the new Department of Housing and Urban Development’s headquarters (above), designed by brutalist architect Marcel Breuer, reflected the federal government’s desperation to get “great” right this time. Part of Johnson’s housing drive was new construction, including further attempts to fix up past errors at public housing projects such as Pruitt-Igoe (below). But federal dollars could not offset another emerging problem. Industry was migrating out of cities—and even out of the country.

Missouri Historical Society/Mac Mizuki Photography Studio Collection

Chicago Tribune

STOP THE SLUMLORDS. Landlord exploitation of black families was the focus of Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1966 housing drive in Chicago. King’s emphasis on class—poor versus landlord—was one Reuther shared. King also pushed for “open housing,” integration of heretofore white neighborhoods. Here are the Kings at 1550 South Hamlin Avenue, a house they occupied to publicize landlord neglect.

Associated Press

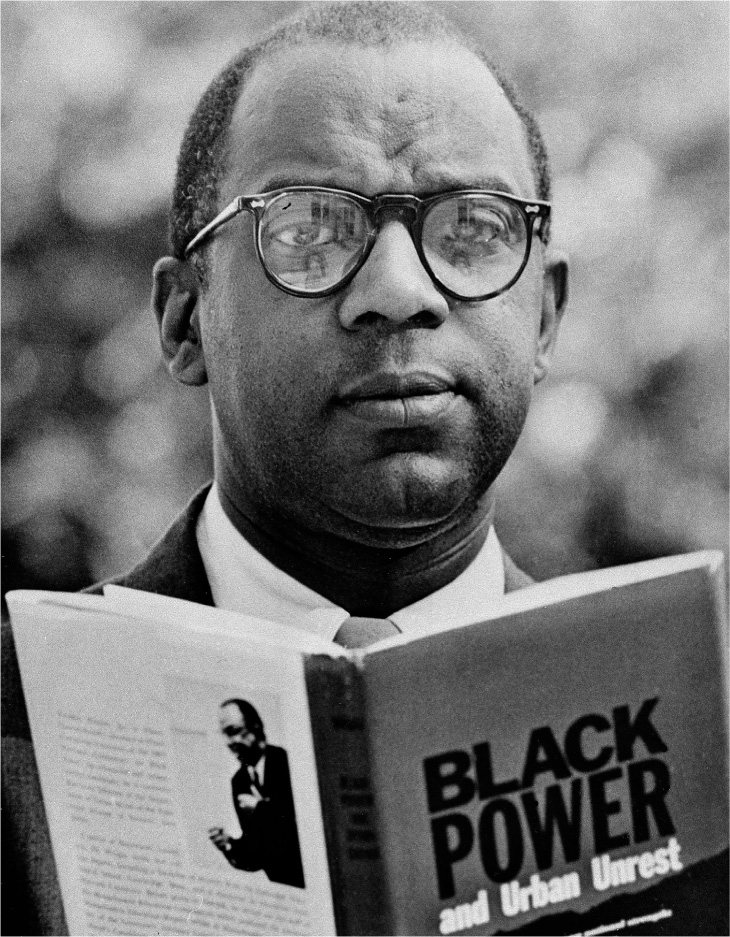

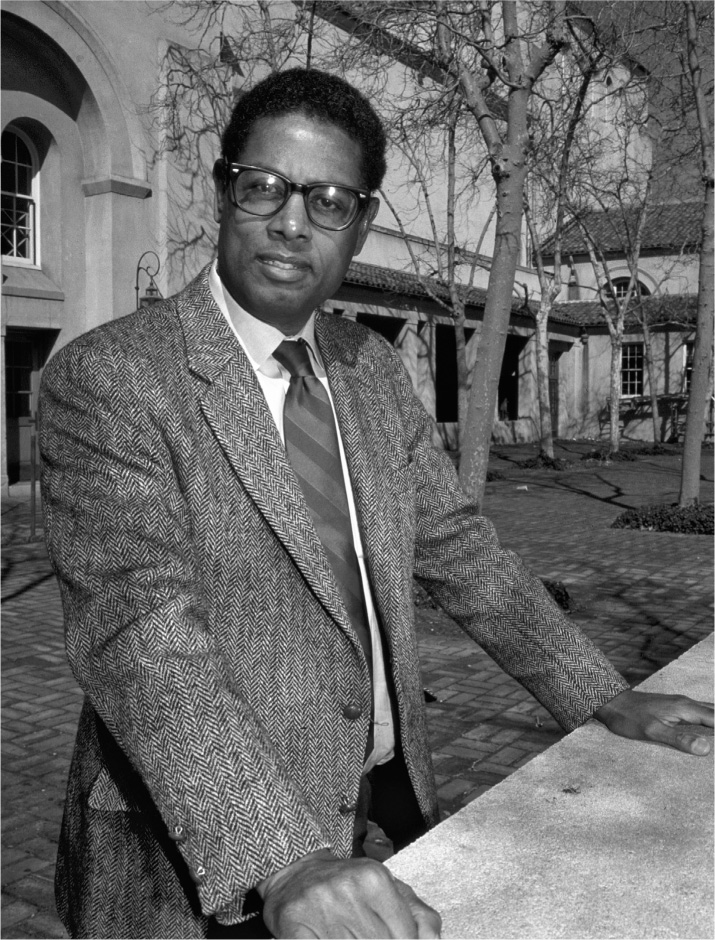

BUILD IT YOURSELF. Other black Americans thought the black community should turn inward to solve its problems. Among them were Nathan Wright, an Episcopalian minister in Newark (above), and a young economist named Thomas Sowell (below).

Getty Images/John Harding/Contributor

Getty Images/PhotoQuest/Contributor

PLANNING FAILS ON TWO FRONTS. Just as his fellow cabinet members planned the Great Society with precision, so defense secretary Robert McNamara (above) planned the U.S. assault in Vietnam to the last detail. By April 1966, the death toll averaged a hundred a week, and total U.S. fatalities in the conflict numbered more than three thousand. The planning failures abroad mirrored those at home. In the same period, an architecture writer in Greenwich Village named Jane Jacobs (below) offered up another approach: Don’t plan from above. Let the people below make their own plans. Don’t think big, think small. Urban planners too often ignored the “marvelous and intricate order of freedom,” said Jacobs. Given autonomy, a slum could “unslum.”

Getty Images/Fred W. McDarrah/Contributor

Associated Press

LOOKING FOR SOCIALISM. Frustrated with civil rights and community work at home, Tom Hayden, like so many other activists, started to ask big philosophical questions. When in 1965 the chance materialized for a trip to Vietnam, Hayden took the offer, not only to protest the Vietnam War but also to evaluate socialism firsthand. Along with the pacifist Staughton Lynd and Communist Party intellectual Herbert Aptheker, Hayden made a tour of socialist and communist capitals, traveling to Prague, Moscow, and Beijing before stopping in Hanoi. Here Hayden (tallest), Lynd (rear), and Aptheker (eyeglasses) stand with a Buddhist priest. Lynd and Hayden admired North Vietnamese solidarity and concluded that North Vietnam featured a “socialism of the heart.” Below, members of a North Vietnamese air defense unit in Quang Binh province. The trip proved only the first of such for Hayden, who also traveled to Cuba.

Getty Images/Sovfoto/Contributor

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

WOULD AMERICA BE NEXT? Britain’s prime minister, the socialist Harold Wilson (above), introduced new government departments and nationalization plans. In the fall of 1967, a run on the pound ensued, forcing Her Majesty’s government to shut down the London Stock Exchange and devalue the pound sterling. With America also adopting social democratic measures, markets wondered if the dollar would be next. Tension between Fed chairman William McChesney Martin and the president grew. The Fed chair warned America was failing in her mission. Johnson bullied Martin and ignored his data. Frustrations with Vietnam drove Johnson to forgo a second term, but another impetus was Johnson’s aversion to presiding over an inevitability: government austerity. “We don’t have the self-discipline . . . to be great,” Martin concluded.

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

Associated Press

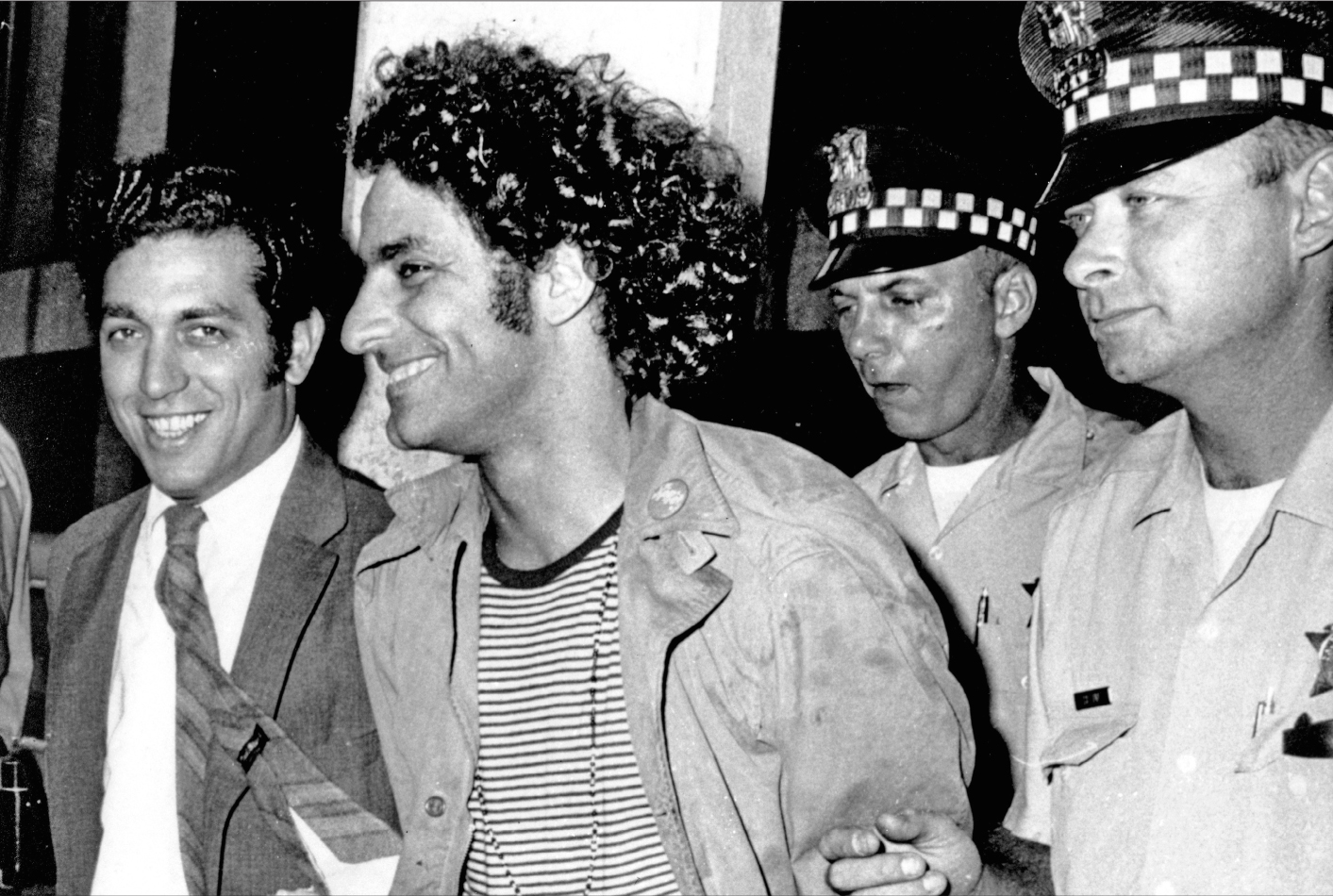

VIOLENT SOCIETY. By 1968 the SDS of Hayden’s student days had imploded and given rise to groups such as the violent Weathermen or the Youth International Party (the Yippies). Ironically, Hayden, who had so hoped socialism would be benign, saw his own organization taken over by Maoists late in the decade. Above, Yippie leader Abbie Hoffmann after an arrest on a charge of unlawful weapons possession. Below, a Greenwich Village town house used by the Weathermen exploded when bombs held there detonated.

Associated Press

Associated Press

ENTER THE COMPETITOR. Unlike American workers, Toyota workers could halt the assembly line and suggest an improvement. The result: better cars for the money—like the early model Corona above. The Corona and the German Volkswagen retailed for well below the Big Three automakers’ economy models.

Courtesy of UAW

AWAY FROM THE WORLD. Sensing future defeats, Walter Reuther struggled in his last years as UAW head. In his final days, Reuther focused on a world he could control, overseeing construction of a grand union retreat at Black Lake, Michigan. Far grander than the Port Huron cabins, Black Lake resembled the rest homes of the Scandinavian social democracies that Reuther so admired.

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

ANOTHER TRY AT “GREAT”—AND SOME SKEPTICISM. In the 1968 presidential election, many of the candidates retooled Johnson’s old “Great Society” logo. “Great for ’68” was candidate George Romney’s (above) slogan. Richard Nixon, the victor, promised not a great but a “just and abundant society.” Many observers found that increasingly liberal courts and government planners were going too far, especially in demanding busing of children long distances in the name of school integration. “Busing is not relevant to high-quality education,” challenged James Farmer (below), cofounder of the impactful Committee on Racial Equality and an assistant secretary at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare in the Nixon administration.

Associated Press

Associated Press

WAITING IN THE WINGS. Ronald Reagan found a new post-Hollywood life when he was elected governor of California in 1966. While in office, Reagan came to tangle personally with the federal government over many Great Society programs, especially Sargent Shriver’s Legal Services. Here Reagan is sworn in as governor in 1967.

Images/Bettmann/Contributor

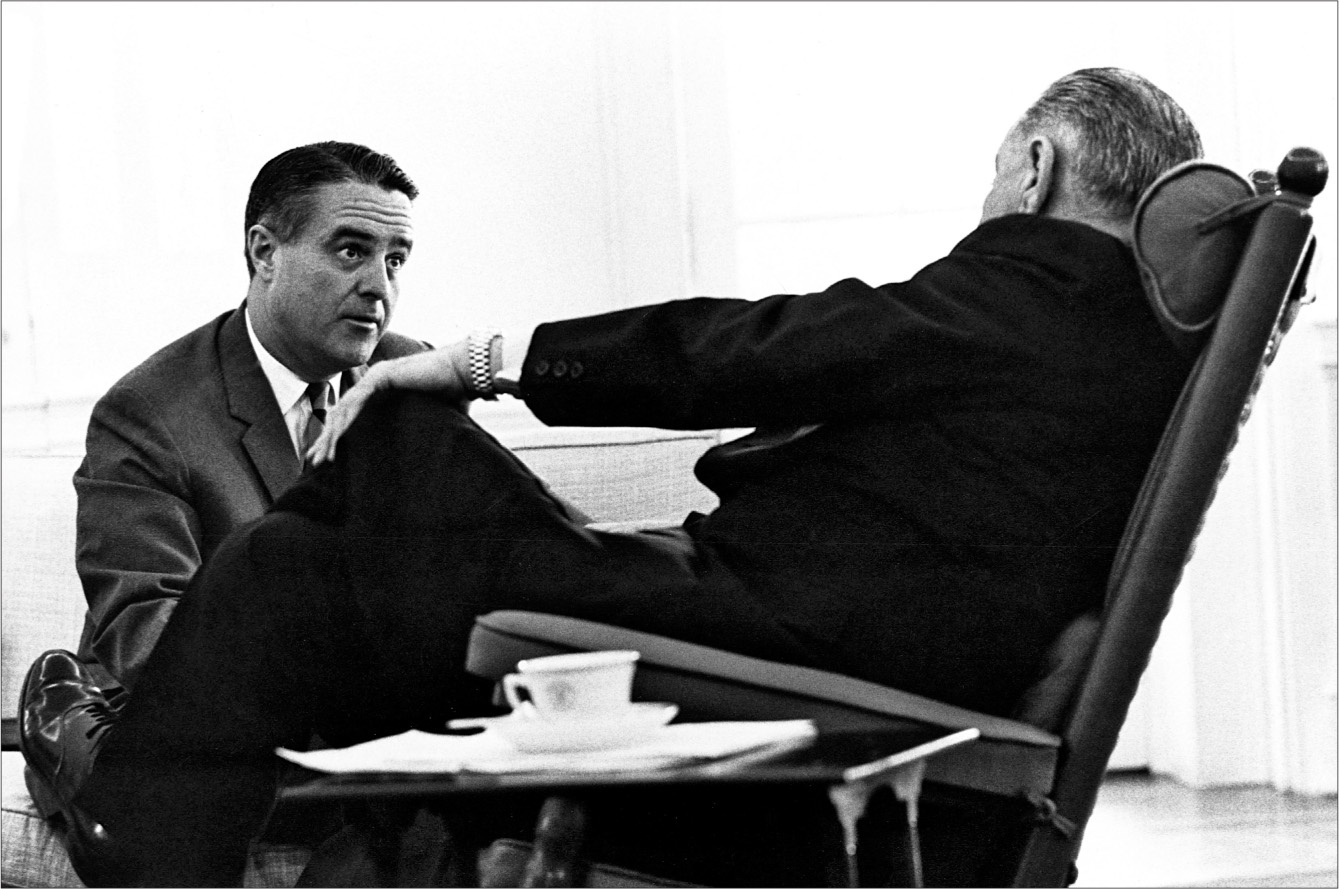

GREAT SOCIETY III. Though the electorate expected Richard Nixon to lead Congress in curtailing the Great Society, the thirty-seventh president ended up expanding it. Advisor Pat Moynihan (above) encouraged Nixon to push through legislation committing to guaranteed income for the poor and working class. The theory was that a simple payment dignifying work would lift the spirits of Americans disheartened by welfare bureaucrats. The legislation failed to pass. By 1971 a new challenge, inflation, disoriented the country. The rise in prices caused a crisis at America’s big unions—no matter how large was the wage that union leaders demanded, inflation meant workers needed more. After confronting the humiliation of a strike by union employees against his own UAW, Reuther’s successor, Leonard Woodcock (below center, in glasses), headed to England, where Toyota was also making itself felt.

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

Associated Press

THE FED VERSUS THE WHITE HOUSE, AGAIN. If Johnson leaned on Federal Reserve chairman William Martin, President Nixon leaned harder on Martin’s successor at the Fed, Arthur Burns (above, at Nixon’s left). Nixon, like Johnson, demanded lower interest rates. Burns, the ultimate professional, resisted. But after Nixon gave Burns the cold shoulder, Burns compromised, laying the groundwork for modern America’s greatest inflation. When the nation’s gold reserves dropped to $10 billion and inflation hit new highs, Nixon tapped new treasury secretary John Connally (below) to fashion a shock package to astound the nation out of its malaise.

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

Getty Images/Grey Villet/Contributor

ROMNEY ON THE OUTS. Housing secretary George Romney was another figure spurned by Nixon. Romney’s humiliation at HUD made a deep impression on his son Mitt (both pictured here). In an unguarded moment during his own 2012 election campaign, a still-bitter Mitt recommended abolishing HUD altogether.

Polaris Images

MANAGED AND CHRONIC. As the country moved into the 1970s, it became clear that new federal programs—whether Kennedy’s, Johnson’s, or Nixon’s—did not cure poverty, as President Johnson had promised. New entitlements merely managed poverty. Above, Pruitt-Igoe’s exterior after water pipes burst. Bad economic news panicked Nixon. So he called a retreat at Camp David and won backing for Connally’s populist shock package. The U.S. imposed tariffs and price controls, lowered taxes for consumers, and closed the “gold window.” Like most populists, Nixon benefited enough from his stimulus to win the next election, but a decade of economic pain ensued. The reluctant Camp David team (in front, from left): Paul Volcker, Pete Peterson, Arthur Burns, Herbert Stein, Paul McCracken, Treasury Secretary John Connally, and George Shultz.

Getty Images/White House/Contributor

Associated Press

MORE FIX-ITS THAT FAILED. In the name of halting inflation, President Gerald Ford in 1974 would form a program to “Whip Inflation Now.” WIN operated under the absurd assumption that the public, through sheer willpower, could slow inflation. WIN also included a tax increase—a challenge to the weak economy.

Intel

AN UNMANAGED CAPITALISM. Even as older industries floundered and consumers struggled, some sectors flourished. In 1971 Intel, a newly publicly traded company, had to navigate the rough waters caused by Richard Nixon’s Camp David program. Still, as its annual report proudly noted, 1971 was the year the young microchip company moved into the black. Intel’s early profits were a portent of the new bonanza that freewheeling high-tech, removed from the old military-industrial complex, would eventually bring.

Associated Press

BOULWARE’S PROPHECY COMES TRUE. In the early 1960s, General Electric’s ideologues predicted that grass would grow in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, if unions drove the price of labor there too high. Over the decades, General Electric indeed pulled thousands of jobs from Pittsfield and other unionized towns and expanded elsewhere. The consequences of the Great Society included “stagflation,” the combination of slow growth and inflation. Blame was placed everywhere, even on foreigners. By the 1980s, U.S. autoworkers would take turns with a sledgehammer on a Japanese car.

Associated Press

Missouri Historical Society/Richard Moore

“THE GOVERNMENT GAVE UP.” A St. Louis city official called the early 1972 demolitions at Pruitt-Igoe “the best show in town.” But to those who had lived there, such demolition represented the final act of a tragedy. Following multiple efforts, federal officials and the St. Louis Housing Authority concluded that they could do nothing more and called the demolition men. “The government gave up,” Chad Freidrichs, a one-time resident, later said.

Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor