Conservation International have classifed Colombia as one of the 17 megadiverse countries in the world, which means it is home to high bio-diversity regions. Amazonas alone boasts 427 mammals, 378 reptiles, over 400 amphibians, and 3,000 types of freshwater fish. All in all, the Amazon Rainforest accounts for more than one-third of all animal species on earth. With such an abundance of life, it’s no wonder conservation is such an important topic in Colombia. Sustainable tourism is the solution to ensure people can come and enjoy the region and its animal species for generations to come (for more information, see the Amazonas chapter).

South American squirrel monkey (saimiri sciureus) at Amacayacu National Park.

SuperStock

Then there are the birds. Colombia is a birdwatcher’s dream. It has the highest avian bio-diversity of any country on earth, and is home to 1,889 species. This represents 20 percent of all the total species on earth. There are also 197 species of migratory birds that make their home in Colombia sporadically throughout the year. Unlike many species in the Amazon, these birds aren’t just relegated to a single region. Prime birdwatching destinations include the Cauca Valley, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the Zona Cafetera, the Amazon, and the llanos Eastern Plains.

Golden poison dart frog.

SuperStock

An often-overlooked destination for serious birdwatchers is the Pacific Coast region of the country. Here, in the Chocó Department, wet forests define the western Andes that slope into the sea and run into Panama’s Daríen Gap north into Panama. Perpetual clouds hang over these tropical forests, providing moisture and condensation that feeds the epiphytes growing on the dense clusters of trees and shrubs, which include orchids. Tanagers are rife in this area; Chocó has even earned an unofficial nickname – the Tanager coast – due to the abundance of these species. But they aren’t the only ones; there are many other species endemic to the area. If you travel south, for example, to La Planeda, between Pasto and Tumaco, you will find a nature preserve covering 3,200 acres that is home to some 240 species of birds.

So what makes this possible? Why is Colombia such a hotbed of biodiversity? The answer lies in the variations of topography and the conditions of the Amazon. The Amazon River has the largest volume of water of any river in the world, and this, with help from the Orinoco River, has led to the creation of the most extensive tropical rainforest on the planet. This is fertile and expansive ground for a number of animal species.

The Andes must also be taken into account. The three cordilleras running through the country are part of the longest uninterrupted mountain chain in the world. These mountains create a wide range of habitats. Rivers drain these areas and create ideal living conditions. Add to that the various expanses of tree-covered open terrain, such as the llanos, and the arid desert regions, and you have the conditions necessary to sustain a huge array of wildlife.

Geology and time have also played a key role in creating these conditions. Look at any map and what stands out about South America is that the continent is essentially an island. It’s connected to the north via a narrow isthmus. At various points since the beginning of time, this land-link has been broken, cutting off migratory patterns from the north and isolating wildlife already existing on the continent, which means competitive conditions were mitigated, allowing more species to thrive. The present connection has been stable for a mere few million years – a relative blip on the timeline of planet earth. During that time, invasions of new migratory animals entered Colombia.

Yellow-eared parrots (ognorhynchus icterotis) nesting.

SuperStock

Birds

Out of the 1,889 species of bird mentioned earlier, some 71 are native to Colombia. Parakeets, finches, hummingbirds, woodpeckers, tanagers, and wrens are particularly abundant here. Some other species of interest include the Cauca guan, chestnut-winged chachalaca, blue-billed curassow, chestnut wood-quail, Bogotá rail, Tolima dove, yellow-eared parrot, black-backed thornbill, silvery-throated spinetail, Antioquia bristle-tyrant, and the Santa Marta tapaculo.

Colombia’s national bird

The national animal of Colombia is the Andean condor. With a wingspan of up to 3 meters (10ft), these carrion birds have been revered since before colonial times, when the indigenous regarded them as messengers of the gods. In recent times they have become a threatened species. Because of this, in 1989 an initiative was undertaken to reintroduce condors raised in captivity into the wild. Dozens have been released into Colombia’s high-altitude páramos, in the Andes, which is their natural habitat. However, lack of efficient tracking methods makes it difficult for scientists to properly monitor these majestic animals, so only time will tell if the Andean condor will make a full comeback.

Mammals and vegetation

As with the birds, Colombia’s varied species of mammals thrive in certain parts of the country, depending on factors as landscape, temperature, and altitude. Many of these creatures are recognizable as woodland animals, like squirrels, mice, rats, tapirs, bats, sloths rabbits, and deer. The opossum is a primitive mammal that has thrived here in part because of the stable nature of the ecosystems. Other rodents in Colombia that are specific to South America include the capybara and chinchilla. Populating the list of Colombian mammals are alpacas, llamas, vicunas, cougars, bears, armadillos, porcupines, monkeys, wolves, and jaguars.

Where you find each of these animals depends on where you happen to be in the country. Some rare and unique mammals exist only at high altitudes here. For example, high in the Andes, between around 3,600 meters (12,000ft) and 4,400 meters (14,500ft), you’ll encounter páramo topography defined by straw grass (pajonal) and other moorland vegetation. Here, deep gorges offer some protection from the harsh weather conditions and icy winds. It’s possible to find thriving shrubs and even the occasional orchid here. Look hard enough and you may just find the footprint of a white-tailed deer, also known as South Andean Deer or huemul, an endangered species.

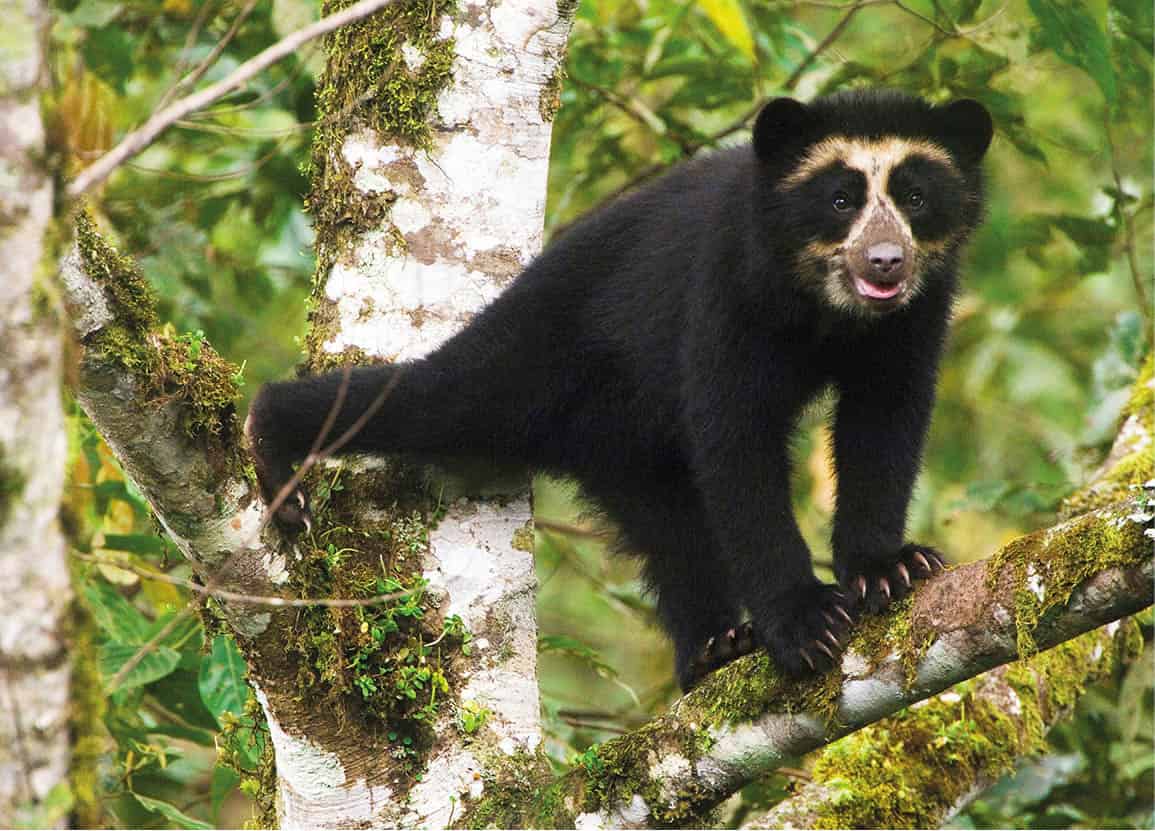

The spectacled bear is a relatively small species of bear native to South America.

Getty Images

Also found at high altitudes in the Andes (over 4,500 meters/15,000ft), are Polylepis forests, defined by gnarled evergreen trees that look like something out of a dark fairy tale. Despite the high altitude, these forests are bright, and they drip water from the moist air on thriving tree ferns. Bromeliads live in abundance here, which is good as they are a principal food source for the spectacled bears in these areas. This is the only bear found in South America, and although it isn’t endangered, it is classified as a vulnerable species due to losses of its habitat. It’s typically a black-furred bear with distinctive beige or red markings around its face, lending it the spectacle look. Its closest relative, the Florida spectacled bear, is already extinct.

At the riverbanks it’s not uncommon to see mountain tapirs and small Andean deer called Pudu. It’s worth mentioning that it is quite difficult to spot mammals in the páramo during the day, as they tend to seek refuge amid the cover of that fringes these areas. At night is when they tend to come out to the moorlands, as the mists that swirl about the dark forests offer protection from the predators of the night. It’s their tracks you have to look for, and often these will include those of pumas on the hunt. Birds in these high-altitude regions tend to be raptors like the mountain caracara and the red-backed hawk.

Speaking of cloud forest, this natural phenomenon occurs only in the narrow strip of the Andean spine that runs from Colombia down to Ecuador and into Peru. In Colombia, these forests are often characterized by tall wax palms, which grow at between 2,000 meters (6,500ft) and 3,000 meters (10,000ft) above sea level on the western side of the central cordillera, and often peak above the cloud blanket. On the eastern side of the Cordillera Oriental Mountain Range, you’ll find dense forests, which blanket the steep slopes and protect the streams running down that feed the Amazon River. These forests are overflowing with lichens, orchids, ferns and epiphytic mosses. This area typically get two meters of rain a year, which maintains the lush forests and help form the many clear-water streams running through them.

As the topography dips below 1,500 meters (5,000ft) the cloud forest disappears and transitions into the lowlands of the Amazon Basin. Here you’ll find an abundance of animal species, including river mammals. For more info, see the Amazonian wildlife photo feature.

Ever dreamed of visiting an island teeming with colorful squirrel monkeys? In Colombia there’s just such a place: Isla de Los Micos (for more information, click here). Here you can walk among hordes of the most playful of critters, and if you’ve got food they won’t be shy about approaching you...

Green iguana at Tayrona National Park.

Alamy

North to the Colombian Coast

The Caribbean Lowlands are home to an array of animals that reinforce Colombia’s reputation as a haven for diverse wildlife. The Caribbean Coast, for example, boasts species that are as unique as the culture itself. One of the most iconic of these animals is the iguana, and they are found all over, although you’ll have to wander away from metropolitan areas to see them in their natural habitat. Usually they are milling about in trees and searching for fruits to eat, but it’s also possible to catch them waddling across roads. More than a few iguanas can be found on the grounds at Quinta de San Pedro in Santa Marta. Also, if you visit Johnny Cay (just off San Andres island), the central grasslands of the island are overflowing with these animals. Because they seem to enjoy a steady diet of food from enthralled tourists, most of them are on the chubby side.

If you’re lucky you might spot a cotton-top-tamarin in northwest Colombia, between the Magdalena and Cauca Rivers. It’s a small monkey notable for a white-patch of fur on its head that gives it a kind of mad-scientist look. Unfortunately these little guys are in danger of extinction. If you’d like to learn more about conservation of this unique species, feel free to contact Proyecto Titi (Calle 77 #65–37; tel: 5-353 1278) in Barranquilla.

The giant anteater also makes its home in northwest Colombia. If you travel between Cartagena and Barranquilla be on the lookout for road crossing signs featuring the image of an anteater. This animal can be found in other parts of South America, all the way down to northern Argentina, as well as in Central America. Fossil remains have been found as far north as Mexico. The animal is characterized by a pronounced snout, and is a close relative of the sloth. It used to exist in the mountainous Andes regions but has sadly since wiped out. Those who wish to see these elegant animals in their natural surrounding will need to visit the Caribbean Coast.

The red-footed tortoise is an animal commonly found on the Colombian coast as well as in southeast Panama. These tortoises are diminutive in stature, and earn their name from the red markings on their legs. Sadly this makes them quite the trophy for exotic pet owners. Still, go to the hottest parts of the coast, like Guajira, Magdalena, and the departments of Bolívar and Atlántico, and you may well see one moseying about in the wild.

Cyrtochilum orchid.

Fernando Vergara/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Conservation in Colombia

Colombia’s various ecosystems and topographies have resulted in a mega diversity of wildlife. Some estimates state that around 10 percent of all the earth’s species reside in this country. Such varied wildlife is a gift to locals and visitors alike, and the hope is that everyone should be able to enjoy Colombia’s rich nature for many generations to come.

To this end there are currently a number of active conservation projects throughout the country aimed at addressing various concerns. Some such projects involve ensuring that Bogotá has clean drinking water for its residents by making sure that the cloud forests of the surrounding páramo continue to thrive. Others involve protecting the Magdalena River Basin, or ensuring sustainable tourism practices are being adhered to in the Amazon.

Climate change is also a threat to various areas of Colombia, including the northern Andean region and Amazonas. The direct danger is to the myriad species that live in these areas. Changing temperatures also have a negative impact on rural areas and the wild regions that surround them. Without action, whole ecosystems will be thrown in flux.

For more information, or to volunteer, visit www.nature.org.

Colombian flowers

It’s hard to address the diversity of wildlife in Colombia without also acknowledging the diversity of plantlife. Over 130,000 plant species exist here, and the richness of climate that allows for this vegetation is also responsible for the wide variety of flowers found in the country. Flower cultivation is so popular In Colombia that it has become an export crop that generates some US$1.5 billion annually. This has even resulted in the creation of one of Colombia’s most famous festivals – Medellín’s annual Feria de las Flores. Some common varietals include carnations, bromeliads, roses, helliconias and even the bird-of-paradise.

The most popular of all the species is by far the orchid. Colombia is home to over 3,000 species of this elegant flower, including the Flor de Mayo. You can see these gems on display at Colombia’s largest botanical garden, the Jardín Botánico José Celestino Mutis (Calle 63 #68–95, Bogotá; tel: 1-437 7060; www.jbb.gov.co; Mon–Fri 8am–5pm, Sat–Sun 9am–5pm), or visit the Orchideorama at the Joaquin Antonio Uribe Botanical Garden in Medellín (for more information, click here). If you book a stay at Hacienda Venicia in the Zona Cafetera, be sure to check out the lady of the house’s expansive orchid garden that she cultivates personally.