The land is known as Antioquia, and the people that inhabit it, Antioqueños. There’s a dominant cultural group here, and they identify as Paisas. This may seem like a superficial designator on the surface, but to experience Paisa culture first hand is to catch a glimpse into a Colombia at once familiar yet slightly askew. It was Paisa industriousness that turned Antioquia Department into the industrial capital of the country. The department’s capital, Medellín, is an example of what Paisas are capable of: here sleek and shiny office parks and apartment towers are connected to even the poorest neighborhoods via one of the most advanced metro systems in the world – something that, the more you spend time here, seems like it could only have ever happened in Antioquia.

View over the Guatapé

Getty Images

Yet outside of the capital city, the pace of life slows to a crawl in the idyllic colonial villages dotting the countryside. Spend time here, eating hearty plates of comida Antioqueña, strolling cobblestone streets amid whitewashed homes and surrounded by rolling green hills, and you can’t help but wonder how something as ugly as violence could ever affect one of the most beautiful regions of the world. Again, Antioquia is as complex as its people, and you could spend years here without ever finding a truly satisfactory answer.

Relaxing in front of a coffee house in Jardín.

Shutterstock

A brief history

The Muisca indigenous people didn’t only exist in the Bogotá region – in precolonial times they could also be found in Antioquia. However, they weren’t the only indigenous group in this area. The southern Antioquia region was inhabited by the Quimbaya people, who were known to produce some of the most detailed gold work of any pre-colonial native group. Other areas of Antioquia were inhabited by native groups, including Carib ‘families’ such as the Nutabes, Catías, and Tahamíes. It was these principal indigenous groups – the Caribs, Muisca, and Quimbaya – that the first conquistadors encountered when they made their way south from the coast and into Antioquia.

Eat

The bandeja paisa is one of the great – and most formidable – examples of Antioquian dishes. It consists of a large plate (the bandeja) piled with meat, sausage, fried pork belly, plantains, and topped with a fried egg. Bring your appetite.

Relations between the natives and the conquistadors started off badly and quickly got worse. The populations of the Quimbaya and Muisca were smaller in Antioquia, and those that weren’t subdued by the Spanish quickly dispersed. The Caribs had the numbers and the will to fight, but were outgunned by the Spanish, and those who refused to live under Spanish rule were soon killed. These encounters were defined by their gruesomeness – so much so that many Caribs killed themselves rather than submit to being conquered. Those who didn’t take their own lives scattered to neighboring departments, like Chocó, which is why today you’ll rarely see Paisas with native blood – the population of Antioquia as a whole is less than 0.5 percent indigenous.

Of the Spaniards who did settle in Antioquia, a great majority of them hailed from Spain’s north coast, particularly the Basque region. For years it was unclear just how many Basque wound up in this area in the early days of the 16th and 17th centuries, as there is almost no record of the Basque language, Euskara, being spoken. Scholars attribute this to the fact that any Basque who wished to resettle in Colombia at the time likely were forced to speak Castilian. This changed slightly after the Spanish Civil War when a new wave of Basque immigrants came to settle in Antioquia, and this time they brought their language with them. However, they flew so far under the radar for so long, that it took an American historian, Everett Hagan, flipping through a Medellín phone book at random in 1957 to realize that a significant portion of the surnames in it were of Basque origin.

Some say that the Paisa reputation for industriousness is a direct result of their Basque roots. A more likely explanation is that the Paisa facility for trade and industry was born out of necessity rather than DNA. Antioquia as a region is geographically isolated and mountainous, meaning it couldn’t sustain very many crops. As a result, Paisa residents were forced to become dependent on trade, first with gold and then, over the centuries, with things like textiles and, unfortunately, cocaine.

Yes, the drug trade in the 1980s and 90s tore through the whole of Colombia, but it was particularly cruel to Antioquia. Pablo Escobar was a natural-born Paisa, and his Medellín Cartel operated out of the capital city. The ripple effect of his operation extended to all corners of this region, but it is only in the last few years that Antioquia is finally beginning to shake off the legacy of one Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria.

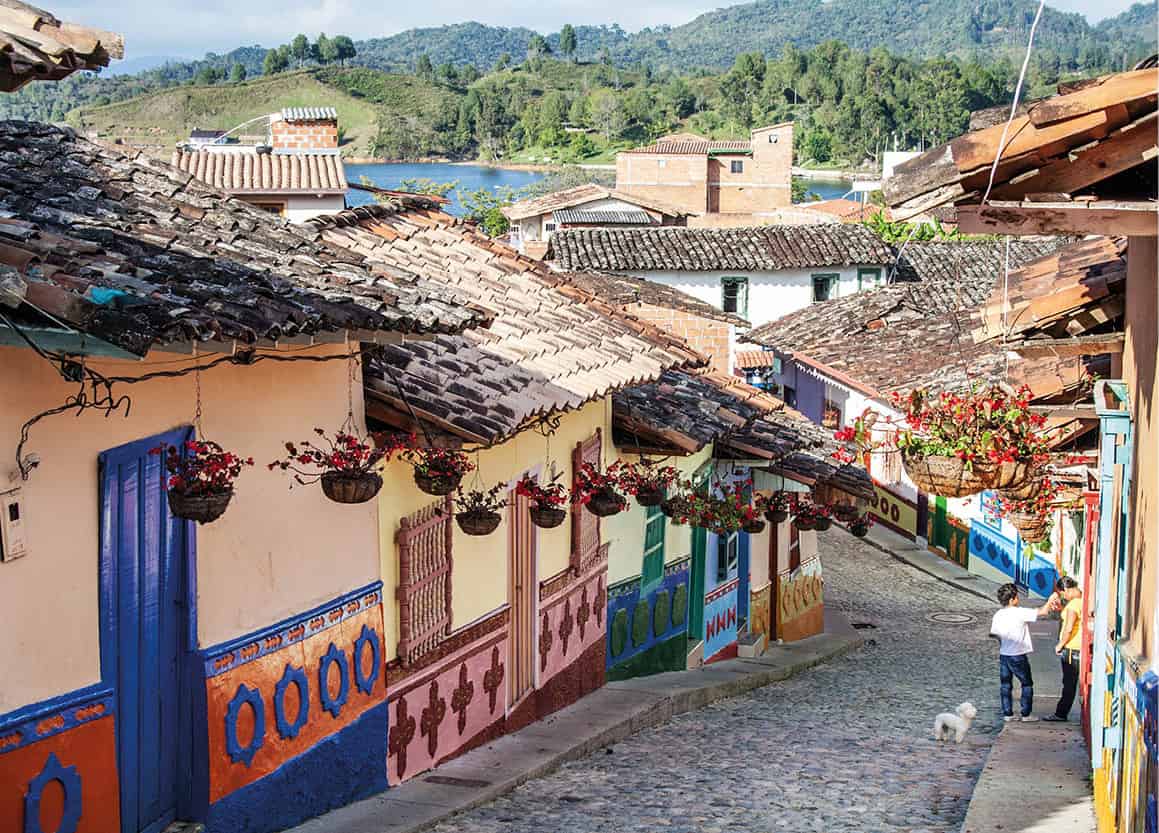

A street full of colorful houses in Guatapé.

Shutterstock

Antioquia and its people today

Today Antioquia has a population of around 6 million people, with over half of them living in the capital city of Medellín (for more information, click here). It seems the Paisas could only have ever existed in this particular part of Colombia. This is especially true when you consider the departments bordering Antioquia. To the west and north is the Chocó, where the culture is dominated by indigenous blood and tribal rhythms passed down through generations from Africa. To the south is the Zona Cafetera, which even the Paisas refer to as ‘frio’ (cold). No, Paisas wouldn’t want to live anywhere else, or be anyone else. After spending even just a little time here, you’ll start to understand why.

Guatapé and El Peñol

When Paisas want to get away for a day trip or weekend excursion, they oftentimes come to Guatapé 1 [map], located about 93km (58 miles) east of Medellín. Once you arrive you’ll see why: Guatapé is adjacent to El Peñol, a town and sleek granite rock, which juts 200 meters (650ft) out of the ground like a bullet, and is one of the major tourist attractions in Antioquia. That said most people prefer to stay in Guatapé as opposed to El Peñol because this lakeside town is an explosion of color and activity, which is most pronounced on the zócalos (lower exterior portion) of the colonial houses that are found here. Even some of the mototaxis are decked out in all the colors of the visible spectrum.

Guatapé is a small lakeside town with hardly more than 6,000 residents, making it even more of an attractive location for those escaping the hustle and bustle of nearby Medellín. On weekends it is positively packed, with families and couples strolling along the malecón (waterfront promenade) beside the lake and enjoying ice cream and other snacks. Here you’ll see plenty of pleasure boats cruising the waters, blaring salsa and vallenato like there’s no tomorrow. One water-based activity that stands out here is the zipline that runs over the lake. Those who come during the week will find the town to be quieter and the lodging options to be much more reasonably priced.

The Stone of El Peñol, also known as the Rock of Guatapé.

Shutterstock

The main plaza A [map] is surrounded by colorful houses and a red-and-white Greco-Roman church, the Parroquia Nuestra Señora del Carmen B [map] (mass times: Sun 8am, 10am, noon, 4pm, and 7pm). The church dates back to 1812 and the interior has many impressive wood carvings and columns. Head over to Calle de los Recuerdos C [map] and see some houses whose zócalos have been embellished with intricate sculptures depicting local families and political events. It’s a unique form of public art. Another religious institution here is a Benedictine Monastery, the Monasterio Santa Maria de la Epifania D [map], which holds Sunday services at 11am, accompanied by Gregorian chanting. To visit, simply take a mototaxi from the plaza.

Just 3km (2 miles) away from Guatapé is the town of El Peñol 2 [map], which was founded in 1714. Although it doesn’t hold a candle to the former as far as lodging options go, people flock here for the rock of the same name, whose summit looks out over a network of interconnected aquamarine lakes like something out of a fantasy-adventure video game. To reach the summit involves climbing 649 steps, which takes about 30 minutes. It’s a must visit for the views alone.

Tip

Pack light when traveling to Antioquia. Many cities and towns, such as Medellín, enjoy a spring-like climate all year round.

Santa Fe de Antioquia

Some 80km (50 miles) northwest of Bogotá is Santa Fe de Antioquia 3 [map], a medium-sized town of about 23,000 residents with a whole lot of colonial history. Jorge Robledo founded this town in the Cauca River valley in 1541. Located at a lower altitude, the town enjoys a more tropical climate, and is hotter than Medellín. The town was initially founded as a gold-mining town, and it was the location of the first such mine in the area. Santa Fe came into its own in 1584, when it officially became the capital of Antioquia. It remained the capital until 1826, when it was replaced by Medellín.

Santa Fe de Antioquia retains so much grandeur from its time as the capital that the town was even named a National Monument of Colombia in 1960. The colonial spirit is thick here, as you’ll see from the narrow cobblestone streets and architecture of the great balconied mansions that line them. This makes for a great weekend getaway for those who want to escape the modernity and tourist hordes of Medellín’s Poblado neighborhood. Having said that, Santa Fe de Antioquia has seen something of a boom in tourism in recent years, with new hotels and hostels popping up all the time. Visitors will be particularly impressed with the annual Christmas and New Year festivities.

Immediately striking is the Plaza Mayor. You won’t find a more beautiful colonial-style plaza anywhere else in Colombia: there’s an elegant center fuente (fountain), which has been supplying Santa Fe with water for the better part of 450 years, with a central bronze statue of Juan del Corral, who was president of Antioquia during a brief period of independence from 1813 to 1826.

The most dominant building around the plaza is a neoclassical cathedral, the Catedral Basilica de la Inmaculada Concepción de Santa Fe (Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception; mass times: Mon–Fri 6.45am, Sat 6.30pm, Sun 11am and 6.45pm), which was constructed between 1797 and 1837 and looks over the plaza from the west. Inside is an 18th-century sculpture depicting the Last Supper. Local artisans built the shrine in the church, with its embossed silver ornamentation, which was then decorated with local gold pieces. Unfortunately, however, the gold was stolen in 1986. In the plaza around the church you’ll also find many artisan kiosks selling souvenirs and handicrafts, as well as local products like honey and dried fruits.

Another standout church is the Iglesia de Santa Bárbara (Calle 11, no. 8–53; mass times: Mon–Sat 8am and 6pm, Sun 8am, 10am, and 8pm), which is located two blocks from the Plaza Mayor. This gem was finished in 1728, at which point it was given to the Jesuits. The front is in Rococo-style (late Baroque) and the interior walls are in Calicanto-style. Adjacent to the church is the Museo Juan del Corral (Calle 11, no. 9–77; tel: 4-853 4605; Mon–Tue and Thu–Fri 9am–noon, 2–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 10am–5pm, closed Wed; free), housing collections of historical items and local gold work. West of the Plaza Mayor is another interesting public area, the Plaza José Maria Martinez Pardo, which contains a statue of Jorge Robledo.

Iglesia de Santa Bárbara.

Shutterstock

Jardín

Jardín 4 [map] is a small town 133km (83 miles) southwest of Medellín that is home to around 14,000 people. It is located in a valley between the western Cordillera Oriental and the San Juan River, and there are actually a number of rivers and arroyos in the area, making Jardín one of the major trout-fishing destinations in Antioquia. There are also a number of trout farms in the surrounding hills. The town itself stands out as one of the most idyllic colonial villages in an area already teeming with idyllic colonial villages.

The history of Jardín is an interesting one in that its original site belonged to the Emberá-Katío, an early indigenous group. In 1863 Indalecio Peláez, a settler, claimed the land here between the two arroyos. The story goes that these first outsiders to arrive in the area were so taken back by the jungle valley, surrounded by bright green hills, that they started referring to it as a garden. Even today visitors will note just how apt this name is.

Then, later in the 1860s, a group of priests arrived, and they officially founded Jardín as a parish in 1871. Their main goal was to create a village with more independence than others in the region; one where locals and farmers wielded control of the municipality. However, in 1882 the president of Antioquia State, Luciano Restrepo, declared it a town. For a while the people of Jardín were predominantly growers of such crops as plantains, sugarcane, and beans.

Tourism eventually overtook other industries as the driving force of Jardín’s economy. Perhaps the main reason for this is because the village is another one of those places that has changed little in the intervening years since colonization. Colonial whitewashed homes with colorful doors and bougainvillea-draped balconies still line the streets, and the plazas and churches pay homage to earlier centuries. As Jardín is such a picture-perfect representation of another time, there has been a huge influx of hotels opening in town. Some estimates place the number at around 40, which is about four times as many as there are in the bigger town of Santa Fe de Antioquia. Visitors can rest assured they’ll be able to find a bed for the night.

As for the village, the central plaza, Principle Park (sometimes called Plaza El Libertador), is where all the action occurs. There’s a large fountain here, surrounded by colorful patio chairs and well-manicured bushes. The stones that make up the plaza come from the nearby Tapartó River. There’s an abundance of shopping, dining, and lodging options around the plaza, and locals sit outside the bars surrounding the plaza whiling away the afternoon hours, while vendors sell fresh fruit juices from carts. There’s a bright white statue here featuring the loving representation of the Madre de Jardín. During the weekend evenings, local horseback-riding enthusiasts ride into the plaza and show off various gaits for the amusement of the locals and tourists.

Principle Park, Jardín.

Shutterstock

Jardín’s neo-Gothic church, the Templo Parroquial de la Inmaculada Concepción, is well worth looking around. Built between 1918 and 1942, the church is a National Monument of Colombia. The striking facade was made with hand-carved stones that parishioners brought from a nearby quarry as a way to atone for their sins. Inside, there’s an impressive altar, made of Italian marble, and an eight-point star in the apse. Impressive sculptures of Christ and the apostles sit behind the pulpit, and there are beautiful stained-glass mosaics throughout.

Visitors to Jardín will also want to take a ride on the cable cars. There are two cable car lines here, which were originally meant to help connect residents from the nearby villages so they could sell their goods in Jardín. These lines are also a gambit to boost tourism, with one traveling from the north to the top of a mountain peak locals call the Alto de las Flores (Flower Hilltop). It affords great views of the town and there’s also a restaurant there. The other line, the garrucha, is an older cable car that runs from the south up over a river to a hill lined with plantain trees. There’s a terrace bar offering good snacks like empanadas, beer, and aguardiente. The views of the town from here are stunning.

Lastly, you can’t come to Jardín without visiting Dulces de Jardín (Calle 13, no. 5–47; tel: 4-845 6584; daily 8am–6pm), a famous local confectioner that supplies candy, chocolate, and jelly to the rest of the country. Even if you don’t have a sweet tooth, be sure to try the curuba (banana passion fruit) and rose petal marmalades. They also serve a tasty breakfast of yogurt with fresh fruit.

Men relaxing at the end of the day in Jardín.

Shutterstock

Reserva Natural Cañon del Río Claro

In a country filled with immense natural beauty, there’s no shortage of dream-like locales teeming with otherworldly charm. One such place is the Reserva Natural Cañon del Río Claro 5 [map]. The canyon was formed by water carving its way through the countryside on a marble riverbed, leaving sheer cliffs and hidden caves in its wake. The running waters here twist and turn their way through Antioquia, creating large pools and gulleys that act as natural bathtubs of the most vivid shades of jade.

Where

The Reserva Natural Cañon Rio Claro and Hacienda Napoles are about 20km (12 miles) apart. Since these locations are at roughly the midpoint between Medellín and Bogotá, it makes sense to visit them on the same excursion.

Reserva Natural Cañon del Río Claro.

SuperStock

The history of Cañon Río Claro

The preserve (www.rioclaroreservanatural.com) is located 165km (103 miles) southeast of Medellín on the way to Bogotá, about a three-hour journey. Interestingly, had the Medellín–Bogotá road never been completed it’s likely this area would have remained little discovered other than by local campesinos and only the most intrepid of backpackers. But the road was built, and a certain Pablo Escobar built his home some 20km (12 miles) away, making it all but inevitable that Río Claro would one day open up to the masses.

It was just such a campesino, Eduardo Betancourt, who discovered the gorge that has now become one of Colombia’s prized tourism destinations. In 1964 Betancourt was losing his livestock to a savvy jaguar, and the humble farmer decided to end matters once and for all. It took him six weeks, but he finally succeeded in tracking the animal to the canyon. Just as Betancourt was bearing down on the animal, preparing for the final assault, the jaguar slipped away forever. However, it did lead Betancourt to the area that would later become the park. There were locals in the area, but they never entered that part of the canyon because they believed it to be cursed.

Betancourt returned to his landowner, Juan Guillermo Garcés, empty-handed but with a tale of a canyon paradise. This intrigued Garcés so much that he never got the tale out of his head. Then, in 1970, a government engineer on a survey mission to build a bridge for the new highway, spotted the canyon from a helicopter. With news that officials had now come across the canyon as well, Garcés enlisted the help of Betancourt to lead him to the fabled area. Over two days they hacked through dense jungle and pulled themselves upriver on a raft, but finally they arrived.

It was intended to be a short trip but Betancourt and Garcés stayed in the canyon for a few months, exploring caves under the canyon walls and building shelters there. It was a good vantage point from which to observe a wide array of animal species that were previously unknown, such as the cave-dwelling guacharo bird. Upon experiencing this bio-diverse ecosystem, Garcés was inspired to protect it, and thus he developed it into a private nature preserve.

Of course the reserve gained more notoriety when Escobar’s profile rose to the point that he was the most famous Colombian in the country. Journalists staking out the famous Hacienda Napoles often wandered over to the preserve, and the area got its fair share of free press. The buzz around the canyon was so strong that on the weekend the new Medellín–Bogotá road opened, some 1,500 visitors descended on Reserva Río Claro. At that point the cat was out of the bag, and rather than fight the momentum, Garcés decided to promote sustainable tourism in the area while maintaining a protected preserve.

What to do and where to stay

The Reserva Río Claro is best visited over two or three days; there are plenty of activities and sights here that are going to keep you occupied for some time, so 24 hours just won’t cut it. Among the activities available is rafting, not only down the river but under great limestone cliffs with water dripping from huge stalactites. The river has sculpted many caves and caverns along the canyon, so caving is also popular in this area. One such cavern cut by the El Bornego creek spans 400 meters (1,312ft) and is made up of tunnels with smooth marble walls. Of course swimming is also popular here, and there’s also a zipline network that covers 500 meters (1,640ft), allowing you to glide over the river and through the tropical rainforest on its banks.

There are also a number of lodging options at the site, including a rustic refuge made up of four different lodges, where rooms have balconies offering views of the canyon. There’s also the Blue Morpho eco-lodge, with two floors of rooms offering forest views. La Mulata consists of two family-sized homes perfect for large groups, and their elevated position makes them ideal for birders.

Tip

Hotel Río Claro is the biggest and most developed of any of the lodging options in Rio Clara, featuring 32 bungalows, a swimming pool, a waterslide, and a restaurant.

Entrance to Hacienda Napoles.

Shutterstock

Hacienda Napoles

In a place called Puerto Triunfo, Antioquia, some 150km (93 miles) east of Medellín, is the former home of the most notorious drug lord to have ever lived, Hacienda Napoles 6 [map] (road from Medellín–Bogotá at km 165; tel: 4-444 2975; www.haciendanapoles.com; Tue–Sun 9am–5pm). Really, calling it a home is a misnomer – this was an expansive estate covering a massive 20 sq km (7.7 sq miles) of land. Pablo Escobar built Hacienda Napoles to be his prime country estate, and indeed he made it one of his principal residences. Today the home itself has fallen into disrepair, and the whole property is now a theme park complete with hotels.

Back in its heyday the hacienda symbolized everything large and ostentatious about Escobar. Not only was it home to a sprawling residence, but it possessed a 1,280-meter (4,200-ft) -long private airplane runway. To put that in perspective, this personal airstrip was large enough to land a Boeing 747. Needless to say, Escobar didn’t build it to accommodate passenger jets.

Certainly vast quantities of drugs were shipped to and from this airfield, but that wasn’t all. A smuggler by trade, Escobar used the landing area to secretly bring in exotic animals. He did this for the singular purpose of building his most prized area of the property: his own private zoo. However, the zoo wasn’t so totally private, as Escobar – in keeping with his carefully cultivated image as a Robin Hood type figure – opened it up to the locals. Here Antiqueños would come and see animals never before seen on the continent, such as elephants, giraffes, and hippos, among others.

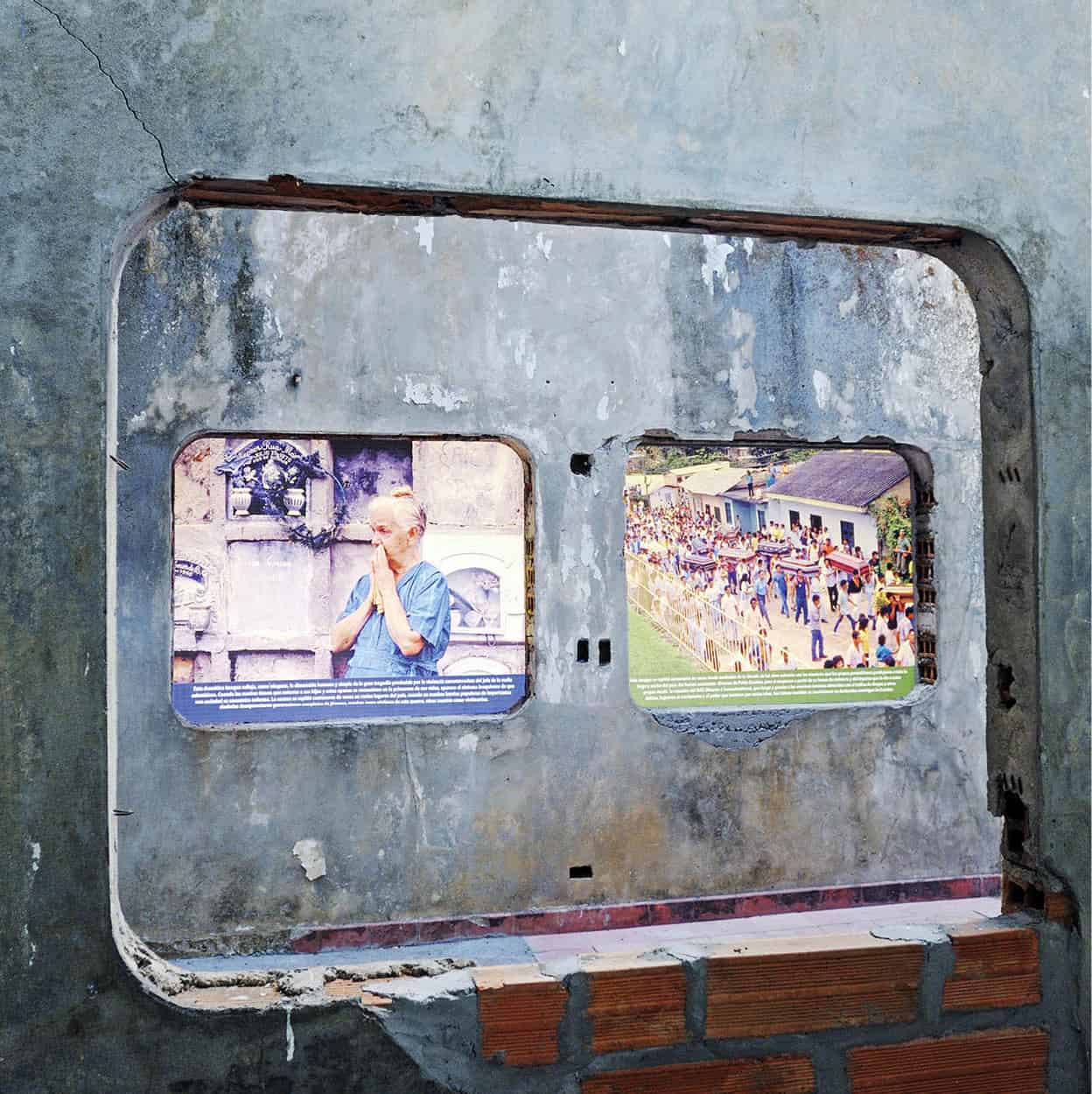

Exhibit at Hacienda Napoles.

Oliver Gerhard/imageBROKER/REX/Shutterstock

In the late 1980s, as Escobar was beginning to feel the pinch of government intrusion into his narco operation, he fled Hacienda Napoles, leaving it to its own slow, inevitable march to the state of decay it is in today. In the immediate aftermath scavengers came to pilfer hidden stashes of cash and drugs, and many of the zoo animals died or escaped. This was the case with Escobar’s hippos, who ran off into the Magdalena River (see box).

The property was eventually taken over by the Colombian government. A private company built a safari theme park, and you even enter the grounds through great tall gates not unlike those seen in the film Jurassic Park. Part of this theme park is the old zoo, which is now a nature preserve featuring a number of animals, including elephants, buffalo, wild cats, ostriches, llamas, and monkeys, as well as an entire herd of hippos. There are even life-size dinosaur models here, which were originally created for Escobar.

As for the main house, it was left abandoned and fell into disrepair. You can still visit it today, and you’ll notice holes in the swimming pool that treasure hunters dug looking for stores of hidden cash. It will likely strike some that the house is on the small side, odd for a man who, at the height of his powers, pulled in $22 billion dollars a year.

Pablo’s hippos

After the Colombian police began to get the better of Escobar and he went on the run, his private zoo at Hacienda Napoles soon became neglected. As a result, some of the hippos escaped, and made their way down to the Magdalena River. Over the years the hippos thrived, even more so then back in their native habitat in Africa. The region agreed with them too, and they soon began breeding in large numbers. Today there are too many hippos in the Magdalena River region in Antioquia to count, but they are all descended from Pablo’s hippos. Rumour has it that the original hippos that escaped from Escobar’s property, the mothers and fathers of this unusual colony, are alive and well today.