DINNER is the most important as well as the most substantial meal of the day. It marks the meridian of gastronomic time, and all other meals are regulated by it. It offers the largest variety of food, and occupies the longest measure of time, and, if only on this latter account, deserves the most attention. In all ages feasting has been associated with both public and private rejoicing, and the evening meal has ever been the most esteemed. Abraham celebrated the weaning of Isaac with a great feast. “Laban gathered together all the men of the place and made a feast” to honour the marriage of Jacob, and Pharaoh kept his own birthday by giving a feast to his servants. Other occasions of the feasts of old were the consummation of the harvest and the vintage, the summer and the winter solstice. The Roman feast was always a supper, and commonly commenced at about three o’clock in the afternoon. These were often great occasions, and were protracted to a late hour. Julius Caesar once gave entertainment to 22,000 guests, and the feast was enlivened by music, dancing, and gladiatorial exhibitions. The feasts of the Hebrews were varied by music, poetry, storytelling and the solution of riddles. It is interesting to note how many of these old customs survive in our modem practices.

DINERS may be classified as diners-in and diners-out. The diner-in is the host who gives the dinner, and in the majority of cases the guests are those who in their turn are diners-in, and who on such occasions reciprocate his hospitality. Besides these, however, there are others, bachelors and spinsters, visitors from abroad, or from a distance, who are welcomed for a variety of reasons, and from whom no invitation is expected in return. It is to these latter, and especially to the bachelors, that this little book is addressed.

ETIQUETTE is the accepted code of manners observed by good society. Its object is not restraint, but graceful freedom.

To be entirely at one’s ease, without impairing the complete ease of others, is to secure the whole purpose and intent of etiquette.

He who has mastered the golden rule, “As ye would that others should do unto you, do ye unto them,” has acquired the true spirit of etiquette, though he may yet have much to learn as to its application to the various experiences of life.

Like the laws of art, the laws of etiquette are deduced from the principles and practices observed by the best masters, and, like communal laws, they came into being in the first instance for the protection of the weak. It was to protect the weak against the strong of the community that communal laws were first enacted, and modern etiquette is an outcome and a survival of the olden spirit of chivalry, which led the brave to deserve the fair. To this day the gentleman is always presented to the lady, however noble his rank may be, and however lowly hers, and this is not done until it has been ascertained that the introduction will be agreeable to her.

Indiscriminate introductions are a sure sign of vulgarity, and no introduction should ever be made without the assurance that it will be agreeable to both parties.

The whole practice of good manners is based upon the gracious bearing of the higher to the lower in the social scale, and the equally gracious recognition of the accepted order of precedence on the part of the lower to the higher. When these obtain, both meet upon a common ground of practical understanding, without loss of dignity on either part.

Some of the earliest and best rules of etiquette may be traced to the early Christian writings and one lesson given in St. Luke xiv. 8-11 is so applicable to the diner-out to-day, that we venture to quote it here.

“When thou art bidden of any man to a marriage feast, sit not down in the chief seat; lest haply a more honourable man than thou be bidden of him, and he that bade thee and him shall come and say to thee, ‘Give this man place’; and then thou shalt begin with shame to take the lowest place. But when thou art bidden, go and sit down in the lowest place; that when he that hath bidden thee cometh, he may say to thee, ‘Friend, go up higher: then shalt thou have glory in the presence of all that sit at meat with thee. For every one that exalteth himself shall be humbled; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted.”

“In honour preferring one another” is also a time-honoured maxim which may well be observed in general practice.

For special occasions, special laws are laid down, and these should be duly observed; but circumstances will often arise when it may be difficult to apply any specific rule, and these will be found to be the real opportunities and tests of good manners. To break a law of etiquette may be the misfortune of many not well versed in the procedure of good society, or new to the particular experience in passing; but in such cases it is always the duty of the master of deportment to observe the spirit which underlies all laws of good behaviour by refusing to, be perturbed by untoward incident, and declining to accentuate awkwardness at the expense of the offender. To observe the laws of etiquette is to act at least after the manner of a gentleman, but to intentionally humiliate another who has unfortunately transgressed is to display the spirit of a cad.

ROYAL MANNERS.—A certain architect unaccustomed to association with royalty was once called upon, in the pursuit of his professional duty, to hand a silver trowel to H.M. King Edward VII., at that time Prince of Wales, in order that he might “well and truly lay” a certain foundation-stone. The architect was an extremely nervous man, and looked forward with some trepidation to the, to him, formidable ordeal. His fears, however, were quite illusory. He was dealing with a master of deportment, who immediately on his arrival at the scene of the ceremonial, sent for him, complimented him upon the designs he had prepared for the building about to be erected, and put him so entirely at his ease that the function became a pleasure instead of a pain.

An equal instance of gracious bearing and true delicacy of feeling is recorded of Queen Alexandra, who on one occasion was taking tea with the wife of a provincial mayor, when, from careful habit, the mayoress placed a lace handkerchief across her knees. Some of the court ladies present observed the act, and smiled their superiority, the one to the other. The Queen noticed both the act and the inaudible comment, and taking her own handkerchief followed the suit of the mayoress, thus putting her hostess entirely at her ease, to the inward discomfort of the ladies of her suit. It was ever so: the best people are always the most easy to deal with.

PERFECT BREEDING.—Daniel Webster, referring to English manners, said: “The rule of politeness in England is to be quiet, act naturally, take no airs, and make no bustle. This perfect breeding has cost a great deal of drill.” There are no surer signs of vulgarity than loud talking, fussy behaviour, and obtrusive conduct, whether upon the part of the entertainer or the entertained. Ostentation on the one part and aggressiveness on the other are equally to be deprecated. Wealth, rapidly acquired nowadays, often places small men in large positions, and thus opens the door of hospitality, without having first graduated host and hostess in the art of entertainment. This leads to mixed gatherings, and often ill-assorted associations. And these cannot always be avoided. To maintain one’s own self-respect, without hurting the feelings of others, by observing quietly, amid unconventional surroundings, the refinements and manners of good society must be the aim of the gentleman.

FORMAL INTRODUCTIONS, as we have already seen, are never made unless it is known that they will be agreeable to both parties, and in all cases the gentleman is introduced to the lady. But this does not prevent informal introductions being made on occasion for temporary purposes. At a dinner party the guests are selected by the host and hostess on the intelligent assumption that they will be agreeable to each other. In such cases it would not be polite of either party to refuse an introduction, but such introductions need not involve lifelong acquaintance, and do not really survive the occasion for which they are made. As elsewhere stated, in such cases the parties bow, but do not shake hands. Introductions made in a ballroom are of the same character, and follow the same usage. The gentleman introduced for the purpose of a dance offers the lady his right arm, and conducts her to the floor of the room. There are, however, introductions which involve the shaking of hands, as when one is introduced to the relations of one’s flancé. These are assumed to be the beginnings of lifelong friendships, and so are inaugurated with more of heartiness and less of formality. Sometimes persons unfamiliar with polite usage desire, for the gratification of their own vanity, introductions to the more distinguished persons present, and these often place others in a very awkward position by asking them to effect such introductions on no other ground than that the person asked is on terms of friendship with both parties. In such cases the person whose kindly offices are requested may, if a man of resource, be trusted to act with discretion towards both friends. He may judge from his knowledge of the two whether the introduction would be agreeable or not, and decline or further it, or he may make direct inquiries and act accordingly.

If the third person is agreeable to the introduction, the difficulty is at an end, but if he declines it, some tact is required on the part of the intermediary in dealing with the proposer, who is often enough one not quick to understand a delicate hint. Persons seeking introductions and not receiving any encouragement should accept the fact as an indication that the proposal is not acceptable, but if too dull to take the hint for a definite reply, there is no alternative but to remind the inquirer that it is a rule of English society only to introduce persons upon the assurance that the introduction will be agreeable to both parties, and to add, “For some reason which he has not given, or best known to himself, Mr. So-and-so does not desire it.” Persons seeking introductions should also remember that similar consideration is due from them to the friend whose kindly offices they seek to employ. No one ought to be asked to introduce two persons unless the one seeking the introduction feels sure that the office will be agreeable to the intermediary. All these points of delicacy are accentuated when the persons proposed for introduction are of opposite sex.

SHAKING HANDS is one of the most characteristic actions of common life, and there is perhaps no action to which more character can be imparted. All kinds of eccentricity find expression in the hand-shake, and that is probably why society has reduced the practice to somewhat formal limits. We all know the “pump-handle” shake, and the “concertina” shake, and the “piston” shake needs no description. Most of us can recall hand-shakes which are combinations or mixtures of all these. The saving merit of these greetings is their undoubted sincerity. Then come the hand-shakes, if they may be so called, which indicate the various degrees of indifference and contempt with which conscious superiority patronises its betters, and the “vice” hand-shake, which crushes the hand of the inexperienced and unexpectant, to the amusement of the cad who inflicts the torture. Besides these there are the three degrees of altitude at which the shake, or what passes for a shake, may be made, and which may be described as the front-door altitude, the first-floor altitude and that of the top flat. All extremes are vulgar, and society generally adopts the middle course. Extremes may be represented by—

“the true good-hearted shake

Of friendship’s hand for friendship’s sake,

When love’s deep power nerves the arm,

And strength meets strength as palm greets palm.”

And,

“The flabby lump of flesh and bone,

That one may shake or leave alone:

An insult in a friendly way

Unfit to scare a crow away.”

There are, of course, occasions when the hand should be shaken, and occasions when it should not; but it may be taken as certain that if the hand is offered it should be accepted, as to refuse it would have the appearance of a slight.

INVITATIONS are issued by the hostess in the name of the host and herself, and the reply should be addressed to both. If the party is to be a small one, the invitations are usually made in writing, but where this would involve the hostess in too much labour, cards, such as are procurable at any fancy stationer’s, are used. They should be issued not too long in advance, and yet sufficiently early to facilitate the convenience of both parties, and to anticipate prior engagements. The larger the party, the longer the notice, is a convenient rule. In the ordinary way, a fortnight is regarded as a reasonable notice, though sometimes a month or more is given. The longer period, though fashionable, is to be deprecated, as it limits the liberty of the guest in a way which may easily become embarrassing. A week or ten days is usually considered sufficient notice for a small dinner party.

An invitation to dinner is a compliment paid, and demands a correspondingly courteous response. It may, of course, be accepted or declined, but whether the one or the other, the decision should be communicated without delay. It is due to the hostess who is to provide the entertainment that she should know as soon as possible for whom, and for how many, she has to provide. Guests who keep hostesses long in doubt as to their intentions, and who at the last moment, as it were, send their regrets, are quite likely, and deservedly so, to find their names removed from the guest-list of the house. Acceptances or regrets should be written in the third person and sent as soon as possible after the receipt of the invitation.

DRESS known as Evening Dress should always be worn at formal dinner parties. The dinner jacket is not admissible except on informal occasions. The Tail Coat with black trousers and boots or shoes and a white or black tie are the proper equipment. Double Collars should not be worn with evening dress, though they are admissible with dinner jackets and other informalities at home, and on informal occasions. Dinner Jackets may be worn by parties of gentlemen dining or visiting theatres, but must never be worn at a formal dinner, at the opera, or at a ball. In private the presence of ladies would seem to mark the distinction, though at home the ladies are inclined to allow the gentlemen more latitude than they enjoy abroad. Waistcoats may be black or white as the guest may determine, but a white waistcoat should be without pattern, ornament, or decoration. The practice of wearing coloured Handkerchiefs tucked in the bosom of the waistcoat has been vulgarised out of use. A White Handkerchief in the breast pocket is the right thing in the right place. The practice of tucking the handkerchief up the coat sleeve as copied from military habit is to be deprecated. It has a slovenly appearance, though it is copied from the smart service. Watch Chains are taboo in evening dress, whether the waistcoat be black or white, but why it is difficult to understand. Evening dress is sombre enough under any circumstances, and might well be allowed this little alleviation, though, of course, all display of jewellery is vulgar. A silk ribbon, or perhaps a fine hair chain may pass if it be black. For outdoor wear, collapsible Opera Hats are the most approved headgear, with a Light Overcoat or heavier as may suit the requirements of the weather. Men are sometimes seen in the streets at the West End of London with no covering over their evening dress, but it looks loud, and is therefore not good form. Gloves should be worn for the protection of the hands, but of a quiet colour, and suitable to the season of the year. The bachelor, as a rule, is not a carriage man, and if the evening be fine, and the distance short, he may with all propriety walk to the house of his host. Should he do so, he must take care, if he turns up the legs of his trousers before starting, to turn them down again before entering the reception-room. If he has worn heavy gloves out of doors, he will also take the first opportunity of substituting the light ones suitable for the reception. He should not offer his hostess a glove which has been handling a cane or an umbrella, twirling a moustache, or manipulating a cigar.

PUNCTUALITY should be observed in all things, and invitations to dinner usually indicate the limits within which the guest is free to suit his own convenience. Fifteen or more minutes, according to the number of guests expected, is usually allowed for the reception, and an invitation for seven o’clock commonly means dinner at 7.15. To delay a dinner is a crime, for which no adequate punishment has yet been discovered,

Beranger, the poet, once gave it as a reason for his invariable practice of being punctual at dinner that waiting guests usually occupy the interim in discussing the faults of the absentee. Those who desire to stand well with all concerned will do wisely to follow the poet’s example.

Failure in this particular on the part of a guest is a slight upon those who are seeking to do him honour. It is the guest’s duty to present himself to his hostess in the most approved form possible to him. His dress should fulfil all the conditions already indicated, and should be of good material, make, and fit; and should bear no mark of haste or carelessness in dressing, or exposure to dust and weather in transit. Let him remember that he has his part to play in the success of the evening, and that it is due to his host and hostess that he should play it well, and so, having dressed himself properly for his part, let him present himself in good time, spick and span as a confection from a band-box if he likes, but free, severely free, from the atmosphere of the made up.

THE RECEPTION.—On arrival, the servants will assist in the removal, and take charge of the outdoor garments, and on reaching the reception-room will announce entrance. The guest will immediately approach and shake hands with his hostess, and then his host. If he is accompanied by a lady, she will precede him at the reception. In no case should they either approach the room, or enter it, arm-in-arm,?Having shaken hands with the host and hostess, and passed a few words with them, the guest will naturally look round the room for any he may expect to see, or any with whom he is on friendly terms. If these are near, he may with propriety shake hands with them, but if at a distance, a slight bow is a sufficient recognition. It is during the reception that the host and hostess make what introductions are necessary, and among these the introductions of those who are to accompany each other to the dinner table. The gentleman will in all cases be introduced to the lady, to whom he will bow, but with whom he will not shake hands. A few words of easy conversation should now break the ice, and prepare the way for the larger opportunity of conversation at the dinner table, after which he will in due course give his right arm to her, and according to the precedence indicated by the hostess, conduct her to the dining-room. Should the passage to the dining-room involve a staircase with the wall on the left hand, the gentleman will give the lady the left arm, that she may take the inside position, as she would were they walking out-of-doors. On the announcement that dinner is served, made by the butler, the host gives his right arm to the principal lady guest, and proceeds to lead the way to the dining-room, followed by the guests, whose order of precedence is regulated by the hostess, who brings up the rear on the right arm of the principal male guest. The seats allotted to the individual guests are usually indicated by cards, bearing their names, or are pointed out as they enter by the host, who, as a rule, remains standing until all are seated. Should it so happen that unavoidable circumstances detain the guest until after the company have gone in to dinner, the servants will conduct him direct to the dining-room, and it will be his duty to make his way straight to his hostess, shake hands with, and apologise to her, and then proceed to his seat with as little fuss and confusion as possible. An apology to the lady who was deprived of her escort by his late arrival would not be out of place. When all are seated the host will be found to occupy the bottom of the table with the principal lady guest on his right and the hostess will preside at the head of the table, with the principal gentleman guest on her left. If the guest is a novice it will become him to avoid prominence, and to watch from unobserved retirement the actions of others. He will have no difficulty in following the due observances of society, if he observes the course taken by those more experienced than himself, and conforms to general usage. Let him in all cases preserve a calm self-possession, and never under any circumstances act in a hurry.

GRACE BEFORE MEAT is pronounced at the desire of the host by some clergyman who may be present, or by himself. In either case the simplest form is the best. “Benedictas, bene-dicat. Amen,” is perhaps the briefest. “For what we are about to receive, may the Lord make us truly thankful” is perhaps the most simple and informal. “Sanctify, O Lord, these mercies to our use and us to Thy service,” is another well-known and often-used grace, while the following well-known collect is admirably available for almost any function which custom regards as suitably opened with prayer. “Prevent us, O Lord, in all our doings with Thy most gracious favour, and further us with Thy continual help, that in all our works begun, continued, and ended in Thee, we may glorify Thy holy Name, and finally by Thy mercy obtain everlasting life; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.”

At rural gatherings where grace is sometimes sung the old quatrain may still serve:

“Be present at our table, Lord;

Be here and everywhere adored;

These mercies bless, and grant that we

May feast in paradise with Thee.”

That laymen are often called upon to say grace, lest it should be omitted altogether, is the reason why we cite these examples here. There are few things more unpleasant than to be nonplussed before others, whether in private or public, and there is no reason why the simple act of saying grace before meat should embarrass any one. The Earl of Selkirk once called upon Robert Burns to say grace, and the Selkirk grace is well worthy of inclusion among these examples.

“Some ha’e meat and canna eat,

Some wad eat that want it;

We ha’e meat, and we can eat,

And sae the Lord be thankèt.”

How extremely embarrassing it may be to be called upon to pray in public was shown some time ago in the case of two well-known barristers, one of whom, a prominent Nonconformist, was accustomed to preach occasionally while on circuit. His learned friend, who was a wit and a caricaturist, could not, on one occasion, resist the temptation to go and hear him. The preacher seeing the gay Q.C. in one of the foremost pews, did not relish the idea of preaching in the presence of his quizzical friend, so, announcing the hymn to be sung before the sermon, he added the words, “After the singing of the hymn, Brother Lock-wood will lead us in prayer.” Brother Lock-wood was quite nonplussed by this announcement. The pulpit had completely turned the tables upon him, and during the singing of the hymn, he lost no time in retiring.

An amusing story is told of Compton, the actor, who on a certain occasion when travelling in the country, called at a village inn and ordered refreshment. Wearing a dress-suit covered by a long black coat, which left his white cravat exposed to view, he was mistaken by the landlord for a clergyman, and was introduced as such to a party of clerics who were about to dine. Invited by a Dean, who presided, to join the party, he was asked to occupy the seat at the Dean’s right hand, and as a further compliment was requested to say grace. There was no possibility of escape, but, being accustomed to overcome stage fright, he was able to rise to the occasion. Not quite sure as to the formula he ought to use, he seized upon the first idea that presented itself to him, and said, in a rich, melodious voice: “O Lord, open Thou our lips, and our mouths shall show forth Thy praise.”

THE MENU is printed for all public dinners, and most private dinner parties of importance. The variation is not great: hors d’œuvres, soup, fish, entrées, joints, game, ice-pudding and savouries, sweets and dessert follow with time-honoured regularity, and host and hostess are always pleased to see their guests do justice to their hospitality. It need hardly be pointed out that vulgarity has a loud voice and can express itself in many ways, in few perhaps more offensively than in eating and drinking. Deportment without awkwardness, mastication without noise, and satisfaction without repletion is the desideratum. What to eat and what to leave is a matter for individual discretion, and the printed menu gives a good opportunity for selection. A famous French cook once claimed that the whole of his menu was arranged on scientific principles, and said that he would not be responsible for the consequences to any diner who omitted any of his courses. But appetites vary and digestions differ, and the diner who finds that certain dishes disagree with him is certain to disagree with the cook. “Know thyself” is a time-honoured maxim which needs to be remembered at the dinner table as elsewhere. A well-ordered table is a pretty sight, with its white cloth, its bright silver, and shining glass, to say nothing of the dainty flowers and the varicoloured fruit, which add so much to its adornment, and yet when one descends from the general to the particular, and squarely faces one’s own small portion, it presents, at least to the novice, a somewhat formidable appearance. In the forefront he is faced with a dinner napkin folded maybe mitre-fashion, a loaf already in its mouth waiting the arrival of the fishes. On the left of his plate he will find a fair array of forks, and on the right a complementary equivalent of knives. There are probably more tools required daily for the feeding of a man’s body than would be needed for its surgical dissection. The writer hopes that this thought will not impair the diner’s appetite. The accompanying diagram shows the disposition of the tools required for the graceful disposal of the food included in a full menu. The number will lessen with the modification of the menu, and vary according to the character of the foods. If hors d’œuvres are included in the menu an additional knife and fork will be found upon the plate ready for use. The knife beyond the plate is for butter or cheese, the spoon and fork for sweets, and the smaller spoon for ice. If oysters are included in the menu a tiny fork is often placed with its prongs turned upwards in the bowl of the soup spoon, and its handle lying diagonally across the outer knife and fish-knife.

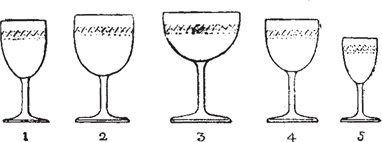

Hors-d’œuvres are often placed upon the table that the guests may help themselves, at other times they are handed round as the other courses are, after the guests are seated. The second dish is the soup, of which there are many varieties, commonly differentiated as “thick” and “clear.” The diner will of course choose according to his taste, but if he wears a heavy moustache he will probably discriminate. The soup spoon, which is the largest of the spoons used, will be found on the right hand of the plate. Soup should be eaten, like other courses, as served, subject to the moderate use of condiments. Small cruets are placed within easy reach of the diners, and should be used with discrimination. The ostentatious use of condiments is a reflection on the cook, and, through the cook, on the host and hostess. Bread, which should always be broken with the fingers, and not bitten off, should never be put into the soup but eaten separately. The plate may be tilted if necessary, but not towards the diner. To tilt it towards the outer edge allows any droppings which may fall from the spoon to reach the plate before the spoon is held to the lips. When dishes are handed round the one handed to a diner is intended for him, and should not be passed on, nor should the diner wait until the whole table is served. Second helpings of any course should not be asked for: it disturbs the service of the whole table When finished the spoon should be left in the plate with the bowl upwards. Wines.—Hosts differ and tastes vary, and in the matter of wines practice is much simpler than formerly. At table the servants will offer such choice of wines as may be suitable for each course. In response you either name the wine or point to the glass made for it. With Oysters and Relishes of all kinds, Vermouth, Sherry, Madeira, or Marsala may be taken. With Soups and Fish white wines, Rhine wine, Sauterne and light white Burgundies go well. With Relêves or Entrées clarets, red Bordeaux, red Hungarian wine, red Swiss wine or Italian wines. So far, the wines have been selected with a view to stimulating appetite. Burgundy may be continued to be served throughout the dinner. With Roasts champagne and other sparkling wines are served. With Coffee Kirsch, brandy. After Coffee liqueurs. Sherry is served with soup, and a small glass is used (Fig. 1). Glasses of various sizes, shapes, and colour are used for the several classes of wines, and these are of various designs. Hock, chablis, or sauterne is served with fish, and a larger glass is used (Fig. 2). Champagne comes round with the joints or game, and a still larger glass is commonly employed (Fig. 3). Though they vary in shape, champagne glasses are always the largest of the suite. Port is drunk with dessert, and the smaller of the gobular-shaped glasses is used (Fig. 4). Liqueurs are usually served after the ice, and in the smallest glass of all (Fig. 5). Claret and Burgundy are served in the glass commonly used for hock; Madeira, and Marsala in the glass used for sherry. Coffee is served last before, or first after, the toast of “The King” at public dinners, and after the departure of the ladies at a private one. Counting the hors-d’œuvres as a course, though it is only an appetiser, Fish is the third course, and fish-knives and forks are used. These will be found the first and last of the formidable array on either side the plate. All usual accessories are served with the several courses, and it is safe to take anything or everything that is offered. As they are used, knives, forks, and glasses are removed from the table, and others, when required, are added. When finished with, knives and forks should be placed side by side on the plate, the blade of the knife towards the fork, and the prongs of the fork turned upwards. Plates are next served for the entrées, which are handed round in silver dishes, from which the diner helps himself. Serving oneself from one of these dishes sideways, as one has to do, is one of the awkwardnesses of dinner service which needs improving upon. Picking and choosing is equally open to suspicion whether done from motives of modesty or greed. While the practice lasts, however, it must be accepted and acted upon with as much grace as possible. The diner uses the spoon and fork in the entrée dish when serving himself to an entrée, and, except where a knife is really necessary, a fork only in eating it. Those who use the right tools for anything always find a smaller number sufficient. Joints and game follow, either as separate courses in sequence, or as alternative dishes simultaneously. With these the accessory vegetables, gravies, etc., are served. The pièce de résistance occupies the plate when placed upon the table, and the accessories are offered to the diner, who helps himself. Sweets follow the joints and game, and the fork, with the spoon in reserve, come on duty. The proper use of the spoon is not that of the knife which, if really needed, should be used. It has its own sphere, in which the fork cannot take its place, in dealing with soft-cooked fruits and ices for instance, but the fork is a much neater and more dainty implement for raising food to the lips, and, held in the right hand, may be made equal to most occasions. Savouries come next, and sometimes the fork requires the assistance of a knife, and sometimes both are dispensed with. Knives and forks are a product of modern civilisation, but “fingers were made before forks” we are sometimes told, and for certain purposes they are preferable to later devices. Bread broken by the fingers, or buttered is lifted to the mouth by them. Cheese-straws and other cheese served on a miniature tray of bread, are eaten in the same way. So are celery, asparagus, water-cress, and artichokes. Dessert brings the dinner to a close. It is ushered in by the laying of a dessert plate containing a doily, a finger-glass, and a dessert knife and fork. The diner removes the doily to his left hand, and places the bowl upon it, leaving the knife and fork on either side of his plate, and then selects the fruit he wishes to enjoy. Fruit needs very careful negotiation, and many prefer to leave it alone. Bananas, apples, pears, apricots, nectarines, and peaches all require peeling, and for this purpose a knife and fork should be used, as well as in eating them when peeled. Oranges are so pretty from a decorative point of view, and so difficult to treat experimentally, that it is better to leave them to the adornment of the dinner table, and negotiate more intimate relations with them at more convenient seasons. Fruits which require the removal of certain parts, such as grapes with their skins, cherries with their stones, strawberries with their stalks, are difficult to deal with, and some are better left, like oranges, for private consumption. Strawberries may be served with their stalks removed, or the diner may remove them with his fingers, and then using his fork dip them into the cream and sugar on his plate and raise them to his mouth. Raspberries may be dealt with in the same fashion, but few things look more unpleasant on a plate than a pile of ejected grape skins, cherry stones, and the like. It may be fastidious, but one has the feeling that anything which has been in the mouth and has to some extent been masticated, ought not to be seen on the plate again. The spoon may aid the fork in some of these matters, and in the case of crystallised fruits the knife must be called into play. Almonds and raisins and nuts may be manipulated with the fingers. The truth is, the simplest, neatest, and cleanest way of disposing of one’s food is the one which most commends itself to refined acceptance.

TABLE TALK.—At dinner there are ample opportunities of conversation, and it is the duty of the diner-out to save his partner from ennui on the one hand and boredom on the other. The diner-out who exhausted his resources in a gallant attempt to interest his partner in the subject of cheese was scarcely a success, except as an example of the inept. It is an old story, but it is worth repeating as a classic illustration of heroic efforts under trying circumstances. “Do you like cheese?” was the first venture of this unfortunate young man, uttered in a subdued tone of voice, but only to elicit a negative reply. “Does your brother like cheese?” was the next inquiry after an impressive pause. “I have no brother,” was the gentle response. Things were getting desperate, but our hero dared another query before he finally succumbed, “If you had a brother do you think he would like cheese?” This appears to have finished the conversation, for no answer is recorded. The gentleman in this case did his best to entertain the lady, and he probably succeeded, but scarcely after the manner of his intention.

THE ART OF CONVERSATION is not that of talking all the time. It is the art of drawing the best out of others, and contributing the best of one’s own to the general treatment of the subject under discussion. Great talkers are not necessarily good conversationalists. Lord Macaulay was a man of vast and varied information. Sydney Smith said of him “He not only overflows with learning, but he stands in the slops,” and another contemporary said in reference to him “I wish I was as cocksure of anything as Lord Macaulay is of everything.” But these were not the qualities of a good conversationalist. Macaulay was a great talker, a fine orator; but conversation in the true sense was hardly possible in his presence. Samuel Taylor Coleridge was another example of those who, having great knowledge and being great talkers, kill conversation. “Did you ever hear me preach?” he once said to Charles Lamb, to which the wit replied, “I have never heard you do anything else.”

TOPICS FOR CONVERSATION are never far to seek, nor difficult to pursue, and, given ordinary intelligence, it should be quite easy to open up subjects of mutual interest, amusement, or edification. Places one has visited during previous holidays spent at home or abroad often provide interesting topics of conversation, in which those who take part can compare notes and relate experiences, humorous and otherwise. Books one has read form another fruitful source of interesting conversation between intelligent companions, when interchanges of opinion on recent fiction, the latest biography, the last book of travel, the youngest and the sweetest of the poets may occupy pleasant intervals. Plays one has seen, and the comparative methods of different actors and actresses in the treatment of the same parts, is another subject of perennial interest, which may well do duty in killing time after the most approved society fashion. Art and Artists, the exhibitions of the Royal Academy, and the other societies of painters may form congenial subjects of conversation in some cases, while Music and Musicians, the first fiddler of the year, or the most lustrous star of the opera or the concert hall, may be the means of introducing an air with variations, which shall not fail of touching a sympathetic chord. Sports, Pastimes, and Hobbies all have their votaries, and a match at Lord’s, a boat-race on the river, and such society gatherings as are represented by such words as Hurlingham, Ascot, and Henley, may serve to revive pleasant recollections and suggest interesting reminiscences, which may more than suffice the occasion. Ladies are much more interested in sport than they were formerly, and this opens a wide field for interesting conversation. Politics are best avoided, as differences of opinion should not be allowed to interfere with the social harmony of the hour, and even in gatherings of no more than two persons heated argument and embittered controversy are frequently the result of party discussion. Public Men and Women are fair objects of fair comment, and the men and women of one’s common acquaintance may often be the pleasant subjects of pleasant remark, though the criticism of one’s friends is always a delicate matter, and good taste, no less than good nature, demand tact and resource. Some people have an unhappy knack of placing their partners in very awkward positions when discussing common friends, and many an estrangement has followed upon a remark which should never have been made, or which, if made, should never have been repeated, and even the tacit acceptance of a remark which the hearer may not approve and may not care to controvert has been taken as an endorsement of the opinion expressed, and quoted as such with unhappy results. The desideratum under such circumstances is a sufficient tact and resource to steer the conversation into a new channel when rocks loom in the distance and breakers roar ahead.

TACT.—Some questions are much easier to answer than avoid, and yet wisdom demands that they shall be avoided at all hazards. Mr. Sims Reeves gives a good illustration of the tact required under some circumstances in his Jubilee volume of “Reminiscences.” He tells us that the late Sir Michael Costa was in the habit of sending as a present to his friend Rossini, at Christmas time, a fine Stilton cheese in prime condition. After the production of his oratorio “Eli,” Sir Michael sent the usual Stilton, but accompanied by a copy of the score of his new work. What passed between the two friends by way of criticism is not known, but it is recorded that a friend of Rossini’s, anxious to hear his opinion, asked him what he thought of the oratorio. “The cheese was excellent,” was his only reply. Kemble was once placed in a similar difficulty by a persistent critic, who questioned him as to his opinion of Mr. Conway, a young actor of his time. “Mr. Conway, sir?” he said. “Well, Mr. Conway is a very tall young man.” “Yes, of course, I know that,” said the inquirer, “but what do you think of him?” “Oh! think of him, yes, exactly. I think,” said the imperturbable actor, “Mr. Conway is a very tall young man.” A similar story is told of a famous German ’cello player, who was interrogated as to the merits of a certain French violinist of his acquaintance. “He haf a verra fine insthrument,” was the reply. “Ja, ja, I know zat is obvious, he haf a fine insthrument, but how does he blay?” “Blay? I tell you he haf a verra fine insthrument.”

Reputations are not lost and actions for slander do not lie when people answer as discreetly as these professionals did. Let us hope the reader may never be involved in a difficulty of the kind, but if he is, to be forewarned is to be forearmed, and example is better than precept. The illustrations given will show an adroit manner of preserving the qualities of some very good friends from undue vivisection.

AWKWARD SITUATIONS will often arise from want of care in general conversation, and one cannot be too careful how one speaks of other persons in mixed company, for one never knows who may be within hearing of their remarks. According to a Stuttgart musical journal, several ladies and gentlemen were, on a certain occasion, travelling together in a railway carriage from Dresden to Leipsic. They were mostly strangers to each other, but the conversation soon became general. One lady, who had been present at a performance of “Euryanthe” at the Court Theatre the night before, passed some very severe strictures upon the production of the work. “Worse than all,” she said, “that Madame Schröder is much too old for her part; her singing has become unbearable,” and then turning to the gentleman sitting next her she said, “Do you not think so too?” The gentleman looked somewhat amused, and then replied somewhat coldly, “Would you not rather tell all this to Madame Schröder herself? She is sitting opposite to you.” What the lady’s feelings were must be left to the imagination; but, recovering from her surprise, she turned to the singer with many confused apologies and said, “It is that horrid critic Schmieder who has influenced my judgment concerning your singing. I believe it is he who is always writing against you. He must be a most disagreeable and pedantic person.” “Had you not better tell all this to Mr. Schmieder himself?” calmly replied Madame Schröder. “He is sitting beside you.” Two imaginations would hardly be equal to describing the lady’s sufferings during the remainder of the journey.

In speaking of people who are absent, it is always best to observe the golden rule, and if there are no pleasant things that can be said about them, to remember that “the least said is soonest mended.” As some writer has well said, We certainly owe it to our common humanity, to show the same consideration for men and women that we do for a picture, by taking care to look at them in the best light.

But conversation at dinner parties is not necessarily limited to two persons, and if the company be small and the story a good one, there is often no reason why all should not benefit by it. The direction of general conversation must a ways be left in the hands of the host, and it is simply rude for any guest, however distinguished, to monopolise it. A good host is, however, alert for the amusement of his guests, and if he sees a group evidently enjoying a good story, he may request that it shall be told for the benefit of the whole party. In such cases the story should be told to the host or hostess, that others may hear, but only at their request.

Loud Talking should be avoided, though when many are engaged in conversation it is sometimes difficult to make oneself heard, say, across the table by one’s vis-à-vis without raising the voice. Perhaps the best rule is to avoid conversation that cannot be carried on without effort, and that leaves one open to the risk of a sudden cessation of the general conversation, throwing one’s own vociferance into all too bold relief. A very amusing story may be told here, illustrating the awkwardness which may arise under such circumstances, and which may lead up to some remarks on telling stories which may perhaps be helpful to the diner-out. The story itself, though rather a difficult one to tell, if well told, never fails of great amusement.

Dr. M’Gregor of Edinburgh owned a parrot which was remarkable for the clearness and distinctness of its words. One of its sayings usually repeated after hearing any unusual sound was “Great Scott, M’Gregor, did you hear that?” At a dinner-party given by the doctor an elderly lady made a remark under the circumstances indicated above which attracted the parrot’s attention, and who commented upon it in his usual formula, “Great Scott, M’Gregor, did you hear that?” The lady, annoyed at what she called the vulgarity of the parrot, informed the company that she had a parrot which, although exceedingly clever, was never guilty of coarse language, and who usually addressed visitors with the phrase, “Funny thing! what are you doing there?” The doctor asked the loan of the lady’s parrot, that his own might profit by its superior culture, and gaining her consent, dispatched his unwilling butler to fetch the missionary bird. The butler was met with the usual formula, “Funny thing! what are you doing there?” to which he answered roughly: “You ugly brute! I shouldn’t have been here but for you!” and taking the cage with him returned to the doctor’s house. The lady welcomed her pet with its own words: “Funny thing! what are you doing there?” and to her intense disgust was answered in the words of the butler: “You ugly brute! I shouldn’t have been here but for you?” This was naturally too much for the doctor’s parrot, who immediately screamed out: “Great Scott, M’Gregor, did you hear that?”

Withdrawing.—At a signal from the hostess, the ladies rise and the gentleman nearest to the door opens it, that they may proceed to the withdrawing-room. Cigars and wines and the last new stories are then discussed by the gentlemen, until such time as the host feels that they are due in the drawing-room, when he rises and leads the way. The time spent over dinner—and it is the last thing in the world that should be hurried over—usually leaves but little time for after-amusement, and in the ordinary way the guests depart soon after the ladies have been joined by the gentlemen, unless indeed the dinner has been an especially early one, announced as preceding a reception. A little music, and a little conversation of a more general character than is possible at the dinner table takes place, but after this the guests begin to disperse. Youth should never be the first to leave, unless under pressure, and when taken the departure should be made with the least possible fuss. Every guest should shake hands with the host and hostess before leaving, and call and leave cards within a week after his visit.

Epicurus never taught

Wild excess and wanton sport;

His to differentiate

Between the coarse and delicate.

Highest good and sweetest pleasure

Follow perfect taste and measure;

Only theirs who choose the wiser,

O wine-bibbing gormandiser.

Follow Epicurus’ suit:

Feed the angel, not the brute.—A. H. M.

Hunger is the best sauce.—Old Saying.

May good digestion wait on appetite and health on both.—SHAKESPEARE.

To know how to eat well is a third part of wisdom.—Anon.

Many dig their graves with their teeth.—FRANKLIN.

Come, gentlemen, let us drink down all un-kindness.—SHAKESPEARE.

Dine with pleasure when you may

Dine with pride another day.—M.

He that is rich need not live sparingly, he that can live sparingly need not be rich.

Be the meat but beans and peas,

God be thanked for those and these.

Have we bread or have we fish,

All are fragments of His dish.

Old Rhyme.

The poor man must walk to get meat for his stomach, the rich man to get stomach for his meat.—FRANKLIN.

Man is a dining animal

Whose wants must be supplied.

Who may not join the cannibal

Must other food abide.

So fish, and fowl, and mammal

He gorges to his taste,

And imitates the camel

In the region of his waist.

And when he’s fed till he can eat no more, His victims join him in a general snore.—A. H. M.

Our life is but a winter’s day:

Some only breakfast and away;

Others to dinner stay, and are full fed;

The oldest only sups and goes to bed.

Large is his debt who lingers out the day;

Who goes the soonest has the least to pay.

CORNOOH.