To all active temperaments, something to do is a necessity, and to compel such to inactiivty is to inflict them with boredom. But here, as in everything else, “variety is the charm of life,” and the minor social functions such as “At-Homes” and unpretentious evening parties are in danger of becoming wearisome inflictions if new interests are not constantly introduced. Such games as Table Tennis, and games of this class require more physical skill and energy than many people care to employ on indoor recreations, and so become the exclusive enjoyment of the younger and more vigorous. Competitions in mental skill afford quieter means of occupation, which appeal with greater acceptance to the older members of the company, and as in the nature of things, many of these can be played without in any way interfering with the amusements more congenial to others, they may often be employed together, and so cover the whole ground of recreative necessity. To facilitate such amusements, the publishers of fancy stationery have issued materials for card competition games in considerable variety and requiring varying degrees of skill, specimens of which by their courtesy are included in the following pages. To those who find sufficient pleasure in the exercise, prizes may be no inducement, but as a rule in these days they excite competition and add to interest. In all cases they should be of moderate value and be more treasured as souvenirs of happy occasions than for their intrinsic value. The following cards, published by Messrs. Delgardo & Co., Ltd., are supplied in boxes of twelve with pencils and cards attached, and with a card containing a key to the solution of the several puzzles. In the following examples the answers are given in the right-hand columns in the space left blank on the actual cards.

EXPLANATION.—Each group of letters represents a well-known proverb; the words of which are in’their proper order but the letters of each word are transposed

| EETRBTELATTANHREEVN | . | Better late than never |

| VEEYRODGAHSHSIDYA. | . | Every dog has his day |

| LITLSTREWASRUNEPED | . | Still waters run deep |

This Game consists of 21 Proverbs

| Letters spell name of town when properly arranged |

County in which the town is situated |

Name of Town | |||||

| THYOAMRU | . | . | Norfolk | . | . | YARMOUTH | |

| TNOSDHEU | . | . | Essex | . | . | SOUTHEND | |

| SOCNETRAD | . | . | Yorkshire | . | . | DONOASTER | |

This Game consists of 24 Towns

| Letters which spell title of book when properly arranged | Name of Author | Title of Book | |||

| LEEWRVYA | . | . | Walter Scott. | . | Waverley |

| LKEUOBEHAS | . | . | Charles Dickens | . | Bleak House |

| LEHMAP | . | . | Lord Lytton | . | Pelham |

This Game consists of 24 Titles

In this game the musical terms here printed in capitals are left blank spaces

The young people at the sea-town of BARmouth had watched with interest the attentions paid by Mr. BEN MARCATO to Miss ANDANTE, so that when the engagement was announced her friends did not REST until they had sent NOTES of congratulation. (Numerous words to fill in.)

In this game the names of the newspapers or periodicals here printed in capitals are left blank spaces

The young people of QUEENstown were much interested in the movements of an eligible young bachelor, who was reputed rich and anxious to get married, so that when at last they heard he had met THE LADY of his choice, all THE WORLD & HIS WIFE flocked to congratulate them both. (Numerous words to fill in.)

In this game the names of the books here printed in capitals are left blank spaces

DEAR JESS (Rider Haggard)

Only last week my sister and I, and OUR MUTUAL FRIEND (Dickens) decided to go for A TRAMP ABROAD (Mark Twain), so here we are, in THE HEART OF ROME (M. Crawford) and simply delighted with all we have seen. (Forty words to fill in.)

A well-known Christian name of a woman lies hidden in each sentence. Find the Name.

| It was a ripping race . . | . | GRACE |

| No pastry can beat rice pudding | . | BEATRICE |

| She had a nice berth and voyage | . | BERTHA |

This Game consists of 29 Questions

A well-known Christian name of a man lies hidden in each sentence. Find the Name.

| The bird lined her nest with moss | . | ERNEST |

| On the step, hens were sitting . | . | STEPHEN |

| Her bertha was made of fine lace | . | HERBERT |

This Game consists of 28 Questions

The answers consist of words formed from the letters in HELIOTROPE

| Looked for north and south | . | . | POLE |

| To marry romantically . | . | . | ELOPE |

| What keeps us from despair | . | . | HOPE |

This Game consists of 22 Questions

The answers consist of words spelt with letters found in the word HONEYSUCKLE

| Much heard during an Election | . | . | HECKLE |

| Punishment by an angry mob | . | . | LYNCH |

| A favourite sport . . | . | . | HOCKEY |

This Game consists of 40 Questions

Each answer must be a word ending with RATE

| A rate that gets worse . . | . | DEGENERATE |

| A rate that dwindles to nothing | . | EVAPORATE |

| A rate that is not excessive | . | TEMPERATE |

This Game consists of 40 Questions

Each answer must be a word ending with KING

| A king who was long besieged | . | . | MAFEKING |

| A king who torments others | . | . | PROVOKING |

| A merry, uproarious king | . | . | ROLLICKING |

This Game consists of 40 Questions

Each answer must be a word beginning with ASS (or AS pronounced as ASS)

| A ready, helping ass . | . | . | ASSISTANT |

| An ass used by the Kaffirs | . | . | ASSEGAI |

| An ass cut in halves . | . | . | ASUNDER |

This Game consists of 30 Questions

Each answer must be a word beginning with IMP

| An imp that cannot be taken . | . | IMPREGNABLE |

| An imp that does things off-hand | . | IMPROMPTU |

| An imp that is easily touched . | . | IMPRESSIONABLE |

This Game consists of 34 Questions

The answer in each case must be a word commencing with either Pro or Con

| A Scottish Official | . | . | . | PROVOST |

| A Piece of Music . | . | . | . | CONCERTO |

| A Geographical Term | . | . | . | PROMONTORY |

This Game consists of 24 Questions

Each answer must be the name of a Periodical

| What was the Bazaar called . . | . | VANITY PAIR |

| What was sold at the refreshment stall? | . | TIT-BITS |

| Which paper gave the most realistic account? | . | THE GRAPHIC |

This Game consists of 26 Questions

Each answer must be a food suitable for the different class of people mentioned

| The food for poachers . . | . | POACHED EGGS |

| What birds do undergraduates like | . | LARKS |

| The shell-fish liked by all athletes | . | MUSSELS |

This Game consists of 26 Questions

Each “SAW” is a well-known proverb which will rhyme with the “SEE”

| SEE | SAW | |

| Trial brings a blessing down . | . | No cross, no crown |

| To find the needy do not roam | . | Charity begins at home |

| Squire stampeded, scullion ran | . | Like master, like man |

This Game consists of 20 Proverbs

The answer is in each case the title of a well-known novel

| What was the store called (Dickens). | Old Curiosity Shop |

| Where was it situated (R. Whiteing). | No. 5 John Street |

| When was it opened (Charles Kingsley) | Two Years Ago |

| Who provided the capital (W. Besant) | Ready Money Mortiboy |

This Game consists of 24 Questions

Messrs. Delgardo publish over fifty varieties of card games, and are continually adding to their list. These can be procured through any fancy stationer.

Other varieties of parlour games are issued from other houses. The following are from the list of Messrs. Goodall & Sons, and may be had of all fancy stationers

Each question must be answered by the title of a well-known Paper

| The highest in the land | . | . | . | . | The King |

| The leaders of fashion | . | . | . | . | The Smart Set |

| The dread of all nations | . | . | . | . | The War Cry |

| A. burden on the rates | . | . | . | . | The Idler |

This Game consists of 41 Questions

The answer to each question is a well-known Play

| Where was the ball given? . | . | Haddon Hall |

| Who sent the invitations? . | . | The Private Secretary |

| What did every mother hope to secure for her daughter? . . | . | The Catch of the Season |

| Who served the refreshments? | . | The Geisha |

This Game consists of 40 Questions

Each answer is composed of letters in the word SHAMROCK

| A faithful serving man and true, ’Twas feared he liked the widows too . |

. | Sam (Weiler) |

| Something of early Gothic style And oft describes a maiden’s smile . |

. | Arch |

| Wild waves dash o’er me—spray so light Or placed upon the mountain height . |

. | Rock |

This Game consists of 24 Questions

The answer to each question is a well-known English Cathedral

| Destroyed by fire—restored by Wren | |||

| I rise above the haunts of men | . | . | St. Paul’s |

| The Apostle’s town . . . | . | . | Peterborough |

| Irish mourning and a meadow . | . | . | Wakefield |

This Game consists of 29 Questions

Each answer to be a term used at Cards, especially at Bridge

| What did simple Mary lose? . . | . | Heart |

| What did she play for? . . . | . | Love |

| As her cards were so bad what did she say? | . | “I leave it” |

This Game consists of 24 Questions

Couplets descriptive of the Celebrity or a Play on the Name

| His name is recalled by an ancient town, His works are of great and lasting renown |

. | Carlyle |

| Give a weapon sharp a quiv’ring motion, My name is known from ocean unto ocean |

. | Shakespeare |

| A domestic article gives the sign Of a nation’s hero—yours and mine . |

. | Kitchener |

This Game consists of 24 Questions

Under this heading Messrs. Goodall & Sons publish a double card upon which is printed an account of the festivities held in honour of the coming of age of a young Frenchman. The story is told in English, and blanks are left for the insertion of French words to complete the sense. These are all words in common use by English-speaking people, but as seventy words are required to complete the story, and the prize (if any) must go to the competitor who fills in the largest number in a given time, it will be seen that the competition is a real one, and one likely to create great interest. Some sentences run as follows, “The company included all the (élite) of the neighbourhood.” “The (costumier) had turned out the most (chic) gowns, absolutely (à la mode), etc., etc., etc.

Other Card Games are provided by the same firm which, however, it is impossible to describe in detail here. All About Ma, 32 questions; The Game of Cities, 20 questions; A Musical Tea, 33 questions; A Party at the Zoo, 24 questions; A Periodical Letter, 64 questions; An English Garden, 28 questions; Current Jokes, 22 questions; An Alphabetical Romance, 26 questions; Reverse, 30 questions; A Novel Fleet, 24 questions, etc., etc., etc. These cards, with pencil and tassel complete, are sold in boxes containing twelve cards and a key card, by all fancy stationers.

Acting Charades are performed in several ways. In one form a scene is devoted to each syllable, and a final scene to the whole word, and the syllables and the word are not only acted but uttered at least once in the scenes by which they are represented; in another form the syllables and the final word are acted but not spoken; and in a third the syllables are sounded in the several scenes, but the whole word is not uttered in the final. Either plan may be adopted with a view to simplifying or obscuring the issues, as words may vary in difficulty ef treatment. Whichever plan is adopted the course intended to be pursued should be made quite clear to the audience, who should be told the number of syllables and scenes which will represent the word chosen. The best acting charades are those which can be so arranged that the several scenes are consecutive incidents in one story, and so form a short play. Let us suppose that the word “wedlock” is selected for the purpose. The first scene may well be a reception after a wedding, at which the father of the bride may say to the happy pair casually, “Well, you’re wed at last, and I hope you will be very happy,” shortly after which the scene may end. The second scene may disclose the bride (a month later) seated at her husband’s desk, in which she finds, among his letters, a lock of hair. At this point one of her late bridesmaids enters and fans her jealousy to flame, advising her to demand immediate explanation, and insist on knowing at once whose look of hair it is, after which she leaves. The third scene is the husband’s return, and the first quarrel, during which the benedict, quite unconscious of the casus belli, may say, “Well! if this is wedlock, I think I had better have kept out of it,” after which the wife produces the lock of hair, which the husband immediately recognises as a curl cut from a pet dog he once possessed, and satisfactory explanation follows. This is a rather obvious rendering, and few will fail to solve the riddle, but it illustrates the advantage of making the scenes form a consecutive narrative, in fact, a novelette of real life. Of course this is not always possible, and three or more separate scenes having no connection at least give opportunity for contrast and ordered variety.

Words for Acting.—Sky-lark, snap-shot, madcap, pad-lock, bond-age, ear-ring, neck-lace, night-mare, black-mail, war-lock, man-hood, child-hood, grand-child, grand-mother, bookworm, book-maker, van-guard, war-spite, home-sick, pot-luck, kind-red, wel-come, welfare, fare-well, court-ship, heart’s-ease, sweethearts, love-knot, check-mate, moon-struck, ill-will, sea-son, orphan-age, highway-man, penman-ship, ring-leader, work-man-ship, thoroughbred, cast-away, co-nun-drum, Shake-speare, Shy-lock, Fal-staff, Touch-stone, Ham-let; also words beginning with in, doubling the n—in-tent, in-mate, in-dul-gent, in-constant; words ending in man, as bond-man, bell-man, footman, fire-man, states-man, watch-man, prizeman, sports-man; words ending in smith, as gold-smith, gun-smith, silver-smith, black-smith; names of places, as Ox-ford, Cam-bridge, High-gate, Lady-well, Smith-field, Folk-stone, Swan-age, Black-pool, Red-hill, Hunting-don, Scarborough, and some proper names—as Good-child, Well-beloved, Young-husband, Thorough-good, etc., etc., etc.

Acting Proverbs are played by one or more performers. In their simple form each proverb is acted by a single player, separately, but in some cases a proverb may require more than one performer for its representation. As a rule, the proverbs are performed in dumb-show, but sometimes they are accompanied with monologue. As an example of a proverb acted by one person in dumb-show, take the following rendering of “Honesty is the best policy.” A servant girl begins dusting a drawing-room with a feather broom, when she discovers her master’s purse on the mantelpiece. She opens it and counts the money, hesitates, puts it back again, and goes on with her work. She again opens the purse and takes out a sovereign, hesitates once more, puts it back again, and flies temptation by rushing out of the room.

The following proverbs suitable lor dumbshow performance by single players will suggest their own treatment. “A bad workman always quarrels with his tools” (player imitates the use of saw, plane, chisel, hammer, throwing them impatiently aside, one after the other; finally cuts or hammers his fingers, and dances about with rage). “All is not gold that glitters” (a chemist pretends to test with acid various articles borrowed from the audience, and returns some with a nod of approval, and some with a shake of the head). “What can’t be cured must be endured” (a tramp with a crutch, a loose sleeve hanging, and a patch over his eye). “Forewarned is forearmed” (preparing for burglars). “A penny saved is a penny gained” (transfer a letter from a box marked “post” to one marked “delivery”). “The pitcher that goes oft to the well is broken at last” (imitate the drawing of water at a well, and the dropping of the pitcher on return—lady’s proverb). Proverbs accompanied by monologues.—“A contented mind is a continual feast” (an old-age pensioner). “Fools and their money are soon parted” (a ruined spendthrift). “When the wine is in, the wit’s out” (silly intoxication). “A miss is as good as a mile” (a disappointed marksman). “A guilty conscience needs no accuser” (a criminal determining to give himself up to justice). “Where there’s a will, there’s a way” (optimism under difficulties, and determination to get on). Proverbs for several characters may be prepared with all the elaboration of charades or private theatricals, and almost any proverb may be attempted. “Handsome is as handsome does,” “One good turn deserves another,” “A friend in need is a friend indeed,” “Anything for a quiet life” may suggest their own treatment.

Acting Rhymes are played singly, as proverbs are, but where the rhyme requires it, the rhymer may be allowed to invite the help of another player from the audience. The action is dumb-show. As rhyming words capable of being acted are not always numerous, six or eight players will often be sufficient for one round. One of the company names a word or a syllable, and each player in turn acts a rhyme to it. Care must be taken in the selection of words and sounds, as some admit of too few rhymes to be practical. The sound AKE suggests wake, quake, shake, rake, break, take, bake, and snake, all of which may be acted. Other sounds and rhymes are ANCE—dance, glance, prance, lance, trance, advance, intemperance; OWE—bow, mow, throw, row, blow, hoe, roe, stow, sew; ITE—bite, fight, flight, fright, write, recite, delight. E—bee, flee, knee, free, see, sea, tee, tea, plea, glee. AD—bad, mad, glad, sad, dad, fad, pad. ACE—face, grimace, race, chase, interlace, trace, embrace. AIN—pain, stain, cane, plane, vain, chain, sprain, skein. SAGE, age, rage, wage, gage, cage, stage, page. IDE—hide, ride, stride, bride, guide, bestride, divide. END—bend, rend, blend, mend, defend, descend, distend.—ENCE—fence, defence, indolence, eloquence, consebuence, benevolence.

Games New and Old.—New games are all more or less modifications of old games, just as new tricks are usually adaptations of old puzzles. These new-old games, too, have a way of reverting to their original forms, and there are not a few who affirm that the old games are the best. This must be our excuse if the reader, looking for the impossible, something new under the sun, finds much in the following pages with which he is familiar.

Viva-voce Games are often of more active interest than card games; they are more noisy, and therefore, as some would say, less dull. Man and His Object is one of these. Two persons, preferentially a lady and a gentleman, go out of the room, and the company present decide upon some man or woman and some object characteristic of and belonging to the man or woman chosen, which shall form the basis of the puzzle. These subjects may be historical, political, literary, scientific, or general. They may be universal or local. A great deal of amusement may often result from the choice of some well-known member of the company present, provided, of course, the person chosen does not object. Very funny results have often followed the choice of one of the persons appointed to guess the puzzle. The man or woman may be a well-known character in fiction, but the object should always be tangible.

The following list of men and objects may be suggestive. Alfred the Great and the burnt cakes, King John and Magna Charta, Christopher Columbus and America, George Washington and his hatchet, James Watt and the steam engine, George Stephenson and the locomotive, William Tell and his apple, Dick Whittington and his cat, Wellington and his boots, Nelson and his telescope, Maxim and his gun, Dumont and his airship, Sir John Franklin and the North-West Passage, Peary and the North Pole, Mr. Gladstone and his collars, Mr. Chamberlain and his eye-glass, etc., etc., etc.

Local subjects may include the rector or vicar of the parish and some object connected with his church, or the mayor of the borough and something appertaining to the Town Hall. A local artist and his pictures, a local musician and his violin or piano, a local miser and his money.

The subject fixed, the absentees are called in, and it is their business to interrogate the company seated round, one at a time, the object of the one being to discover the name of the man, and that of the other to ascertain the nature of the object. One question must be asked of each person in turn by each of the interrogators, and they must be questions which can be answered by a “yes” or “no.” The first questions will naturally be “Is it a man?” “a woman?” “a child?” “living?” “dead?” “eighteenth century?” “later?” “earlier?” and so on. These questions narrow down the field of inquiry, and bring the interrogator nearer to the subject. In the meantime the questions as to the object will be interspersed, and these will naturally be, “Is it a manufactured article?” “a raw material?” “mineral?” “vegetable?” “animal?” etc., etc., etc. The two questioners may deal alternately with one person, or may take the company alternately, but they should not both question at the same time, as all the company are interested in hearing the cross-examination. The game proceeds until the puzzle is solved or the interrogators have to give it up.

Sherlock Holmes is a name suggested for a variation of the foregoing game by the Evening News. In this case the “detective” retires from the room, and the company concoct a crime which it is his business to detect. The crime suggested by this popular evening paper is as follows: “Shakespeare murdered Bacon, and threw his body into the River Avon.” All these points are to be elicited in cross-examination in the manner already described. Other subjects of the same kind, but with a real basis in history, will readily occur to the reader. “The Murder of the Young Princes in the Tower,” “The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots,” “The Decapitation of Charles I.,” etc., etc. Perhaps purely fictitious crimes like that attributed to Shakespeare in our first example are better adapted for mere amusement.

How, When, and Where is another viva-voce game, in which the company selects a subject which may be preferentially represented by a single word. The interrogators then proceed round the room, asking three questions, “How do you like it?” “When do you like it?” and “Where do you like it?” and endeavouring to guess the object from the answers given. A simple and of course far too obvious example is the following: “How do you like it?” “Without milk.” “When do you like it?” “After dinner.” “Where do you like it?” “At the table,” or “In the drawing-room.” The obvious answer to this is Coffee, but an enormous variety of subjects may be chosen, representing every degree of difficulty.

The Spelling Bee.—Spelling bees and roller skates came into fashion about the same date, and a wit of the time referred to them as symptoms of the “foot-and-mouth disease,” an ailment then prevalent among cattle. The spelling bee “improved the shining hour,” and incidentally the national spelling for a while, and then died a natural death. The roller skate has grown in popularity; and in view of the deterioration of the modern English winter, appears to have come to stay. The Spelling Bee in the first instance was a mere test of skill in spelling, and it may still be used in its primary form in entertaining young people—and all people are young on festive occasions—with interest, amusement, and profit, if prizes are offered to those who survive the ordeal. If played as a game at a private party the numbers entering should be limited, or the game will take too long. The Interrogator, who should be appointed beforehand, should have a number of words of graduated standards of difficulty written down on paper, and taking the easier words first should put them to the several competitors in turn—a new word to each—who, on failing to spell a word correctly, should leave the group competing until the final round determines the winner or winners of the prizes. The Progressive Spelling Bee adds to the study of orthography a considerable exercise of ingenuity. The first player names a letter, and each successive player adds a letter, with a view to forming a word. The player who cannot add a letter without completing a word loses the game and pays a forfeit. An illustration of this game was given some time ago in one of the daily papers, which unfortunately the writer is unable to name. In this five competitors were supposed to take part, and the first-named the letter “S” to start the word. The second, third, and fourth players in turn added the letters “T,” “I” and “F.” This placed the fifth player in a quandary, for had he added a second “F” and completed the word STIFF, he would have lost the game and suffered forfeit. Happily, he thought of the letter “L,” and so started the train of thought on to the line STIFLE. As only five competitors were playing, this would be a drawn game, unless the players had previously agreed to continue for a second round, or until such time as a word was completed. Had this been arranged, or had there been a larger number playing, the sixth player might have still escaped penalty by naming “I” and prolonging the word in the direction of STIFLING. The object is to postpone the naming of a letter which will make a complete word of those which preceded it, as long as possible, under penalty of a forfeit. This game is sometimes played under the name Ghosts, in which case three failures, which are called “lives,” are allowed to each player before he becomes “dead” to the game. Double Demon Spelling Bee is a development of this game, and opens up larger opportunities of ingenuity by allowing prefixes as well as affixes. In this case each player has the option of adding his letter at either end of the word in process of formation, provided, of course, that he has in view a definite word, the correct spelling of which can be so promoted. Thus, continuing the illustration given above, the fifth player, fearing the letter “F,” which would have completed the word STIFF, and not thinking of the letter “L,” which diverted the word in the direction of the word STIFLE, might still have avoided forfeit had he thought of the prefix “A,” which would have diverted the letters in the direction of the word MASTIFF. It will be seen that this game offers plenty of opportunity for ingenuity, and may sometimes be continued to considerable length. Prizes may be given in place of imposing forfeits, if those failing drop out of the competition one by one until only two are left. These should be judged equal.

Wills and Bequests.—In this game the testator leaves the room, and the player who acts as lawyer writes down on a sheet of paper the various personal belongings of the testator as suggested by the company to the number of, say, twelve. These he will number in order, one to twelve. The list may include all sorts of absurd as well as sensible things, as the testator’s motor-car, his fiancée, her mother-in-law, his temper, his debts, etc., etc., etc. The testator is then called into the room, and in ignorance of the nature and order of the bequests, is asked to whom he is desirous of leaving No. 1, No. 2, and so on, to the end. The names of the legatees are then written down by the side of the bequests, until the list is complete, and then the lawyer reads the will as nearly as possible in legal form. The amusement arises from the incongruity of the allocation of the odd bequests to the several legatees.

Clairvoyance, real or sham, always excites wonder, and the sham has the advantage of promoting amusement. The clairvoyant leaves the room, after taking a careful survey of its appointments and furniture. The professor then, speaking so that he may be heard by the clairvoyant through the closed door, says: “Do you remember the disposition of the various features of the room?” to which the answer will be “Yes.” The professor then proceeds to name various articles, suggested by the company (sotto voce), interrogatively, thus: “The piano?” “Yes”; “The overmantel?” “Yes”; “The clock?” “Yes”; “And the coal-scuttle?” “Yes”; “The settee?” “Yes”; “The picture over the sideboard?” “Yes,” and so on, until a good number of articles have been named and acknowledged. The professor will then place his hand on the coal-scuttle and say: “Which of all these articles am I now touching with my hand?” and the clairvoyant will immediately answer correctly. Why? Because the professor used the word “and” before the word “coal-scuttle,” and this gave the clue to his confidant. So long as the clue is understood beforehand it need not be used to apply to the word immediately following, but to the first, second, or third word after or before its introduction.

The Stool of Repentance is a game which often causes a great deal of amusement. The person who is to occupy the position retires from the room, and during his absence one, who is appointed spokesman, collects from the company, preferentially on paper, opinions or characterisations of the person in question. The absentee is then called in, and the opinions or characterisations are read to him one by one, and he is asked to guess who are the authors of the same. Failure to do so involves a forfeit. Within the limits of good taste, some very amusing opinions may be given and characterisations made, and all should be put to the occupier of the stool of repentance with some such formula as, “Deponent saith So-and-so. Who is your critic?” These should be in the main real but amiable characterisations, but such opinions as: “Deponent saith You are no better than you ought to be,” or, “You are never obstinate when you can have your own way,” or “He would not trust you with his best girl,” or “What you don’t know, isn’t worth knowing,” etc., etc., etc., are admissible at discretion. This game gives a man’s wife a chance not always open to her.

Games which have been called by various names, and which may be described as “Message Games,” come under this category. The simplest form is that of a message or of a proverb which is whispered by the first player to the second, and by the second to the third, and so on, until it has completed the circle of the company. The fun of the game consists in the extraordinary difference which is found to exist between the original message and its final form. Each of the players should pass the message on with as much distinctness as possible, but should take care that it is not audible to any one but his immediate neighbour. In all games of this kind the original formula should be written down on paper, and kept in the possession of the first player, that it may be compared with its own mutilation at the finish of the round. If PROVERBS are used they should be such as are not too short, trite, or well known, though even these will seldom escape transformation in transmission. The following old proverbs may be suggestive: “Get thy spindle and thy distaff ready, and Heaven will send the flax.” “He that hath a head of glass should not throw stones at another.” “Better go to bed supperless than get up in debt,” “It is wit to pick a lock and steal a horse, but it is wisdom to leave them alone.” “They who would be young when they are old must be old when they are young.” “Better ride on an ass with a sure foot than a horse that shies.” If MESSAGES are sent they should be so framed that they may easily confuse the memory, but of course not so difficult as to spoil sport. The following formula which was proposed by Foote to Macklin as a test of memory, may be cited as an example of how to frame such a sentence, but of course in itself it is far too long for the purpose of this game. “So she went into the garden to cut a cabbage leaf to make an apple pie; and at the same time a great she-bear coming up the street pops its head into the shop: ‘What! no soap?’ so he died, and she very imprudently married the barber; and there were present the Piccaninnies and the Joblillies and the Garyulies and the great Panjandrum himself with the little round button on top; and they all fell to playing the game of catch as catch can, till the gunpowder ran out at the heels of their boots.”

Message Games may be made more complex and therefore more interesting, if they take the form of A Telegram, reply paid. In this game, which is played in the way already described, the abbreviated form of the telegraphic style lends itself to confusion and so to amusement; and the interest is doubled when the message has completed its round, and a suitable reply is returned by the last player to the original sender by the same means. RUMOUR or GOSSIP is a name which may be given to another variation of this game. In this case some little piece of harmless scandal may form the sentence which is passed round. Yet another viva-voce game, in which whispers do not count, is one called Shooting Proverbs. In this two persons leave the room, and the company sitting round choose a proverb which in this case should be a fairly well known one, but not so long as to baffle solution. Supposing the proverb to be “It’s a long lane that has no turning,” the first player takes the word “it’s,” the second the word “a” the third the word “long,” and so on until every word in the proverb is provided with a sponsor. If there are more guests than words, the proverb may be begun again, and continued as far as there are guests to represent it. When each guest is fitted with a word, the absentees are called in, and take their place in the centre of the room. The spokesman then calls out: “Make Ready! Present—Fire,” and at the word “Fire” the whole company simultaneously shout the word of the proverb which has been allotted to them, and it is the object of the guessers to discover order in the babel of sounds. The guessers may call for the repetition of the shout with the same formula as often as they please, and they may walk round the room, and listen specially to individual voices to catch definite words as much as they like, until they have guessed the proverb or confessed their inability to do so. In most proverbs there are striking words which, once heard, give the game away. In the proverb cited above, the word “turning” would probably do this; in the proverb “a stitch in time saves nine,” the word “stitch” would be an unfailing clue.

Paper Games. Games that require the use of pencil and paper, other than card games where the cards and pencils are procurable attached, involve some little trouble, as the want of a flat surface upon which to write often results in illegibility, and yet some of these games will well repay the trouble involved. Pictures and Mottoes is one of these. To play this game, pieces of paper folded across the middle are handed to each member of the company, and each is asked to write on one side of it the subject of a picture. This may be “The Coronation,” “An Alpine Scene,” “A Farm Yard,” “A Storm at Sea,” or any well-known picture, or any subject capable of pictorial treatment. When this is done each person refolds the paper concealing the subject written on the inside, and hands it to his right-hand neighbour, who, without opening it, writes a motto on the outside. These may be well-known proverbs, or lines, or couplets from poems, such as are often placed by artists beneath their pictures. This done, the papers should be handed to the next person on the right, who in turn should read out for the benefit of the company, first the subject, and then the motto. The result is not always congruous, but very often subjects and mottoes are found to be very suitably matched. The writer remembers several apposite examples which resulted in one game in which he took part. The picture, “A Farewell at a Railway Station,” had for its motto “Oh! for the touch of a vanished hand, and the sound of a voice that is still,” and the picture “Cattle Grazing” bore the inscriptive motto “The nearer the bone, the sweeter the meat.” In announcing the result it is sometimes found better to collect the papers immediately after the mottoes have been written, and hand them to some one to arrange, and give thereadingsin some appropriate order later on.

Adjectives is a name given to a game in which each player is supplied with a piece of paper, on which he is required to write several adjectives. These are collected by the principal player, who reads a page or two from some book, substituting, without regard to sense, the adjectives supplied by the players for those printed in the narrative. The result is both curious and amusing.

The Ancient Game of Crambo may still be included among parlour games. In this two pieces of paper, of different colour, are handed to each player, who is asked to write a noun on one colour and a question on the other. These papers are collected in separate hats, well mixed up, and again distributed. Fach player has then to make up two or more lines of verse at once including the noun and answering the question. These are then collected and read out, for the general amusement.

The Game of Consequences is an old paper game which seems to enjoy perennial youth, and which with young people and at Christmastime, when the older games are commonly the most popular, can usually be trusted to cause general amusement. It is a “personal” game, and must be played with discretion, and strictly within the limits of good taste. a half-sheet of note paper is required by each player, who proceeds to write the name of a gentleman at the top. Each player then folds the paper to conceal the name and hands it to his right-hand neighbour. At the top of the paper as folded each player then writes the name of a lady, folds the paper again, and passes it on. Each player then writes the name of a place, folds the paper, and passes it on as before. What the gentleman said is next inscribed, and after folding and passing the paper, what the lady said; after which what the gentleman did, and what the lady did, are added separately in, and finally the consequences finish up the story. When the papers are completed, each player in turn, or one appointed for the purpose, reads out the results in the following formula: What’s-his-name met Mrs. or Miss So-and-so at such a place. Mr. What’s-his-name said this or that, and Mrs. or Miss So-and-so said that or this. Mr. What’s-his-name then did thus-and-thus, and Mrs. or Miss So-and-so said one thing or another, and the consequences were—#x2014;Though commonly the names of persons present, or persons known to members of the company are used in this game, those of public men and women, historical persons, and characters in fiction may often be used with great amusement.

Games at Forfeits commonly involving osculatory exercises are often popular with young people at Christmas-time, and within the home circle need not be disdained by their elders. Usually the criers of forfeits fail in the variety and suitability of the inflictions they impose, and any one who would invent a number of new penalties, which should be humorous without being open to objection, would confer a benefit and enable many games to be played which are at present taboo. Many of the old ordeals are somewhat trying. When a lady is condemned to stand under the mistletoe and spell opportunity, she is asked to give an opportunity from which she may not unnaturally shrink, and when she is ordered to stand in the centre of the room and repeat Nelson’s famous signal at Trafalgar, “England expects that every man this day will do his duty,” she really needs all the courage of the combined fleets. That there are those to whom such impositions would be really painful is a sufficient reason why they should be applied with discretion, and that, the blindfold conditions under which the penalties are dispensed renders impossible, tinder these circumstances it is best that only those should take part in these games who are prepared to accept the consequences. The writer well remembers being distressingly perturbed when, a small and bashful boy, he was ordered to “Bow to the wittiest, kneel to the prettiest, and kiss the girl he loved best in the room,” and it was only when his mother pointed out to him how easy it was for him to discharge all his obligations at her feet that he rose to the occasion, and found, not for the first nor the last time, “a happy issue out of all his troubles” in her arms. Other osculatory penalties are “Kiss the four corners of the room,” in which, of course, the lady is sure to find a gentleman ready to help her to redeem the behest; “Kiss the flowers on the carpet,” when the “weeds” will sometimes be found more numerous than the flowers; “Measure six yards of love ribbon,” effected by kneeling on cushions, face to face, with some chosen one joining hands in front, and then extending them sideways to their extreme limit, and thus bringing the lips together six times in succession, and “kissing rabbit fashion” brought about by nibbling rabbit fashion at the two ends of a piece of string until the lips meet and ratify the compact. A prettier forfeit of this kind may be borrowed from the “Valse Cotillion” and called, for this purpose, “The Mirror of Venus.” In this ease the lady sits with a mirror in one hand and a pocket-handkerchief in the other, while the gentlemen pass behind her chair and look in the mirror as they pass. One after one she essays to wipe the reflection out with her handkerchief, until she sees that of the face she chooses, when she looks up at the real face and—kisses meet.

BUT exploiting worthy Whewell:—

Though his words were rather cruel—

When, in spite of pap and gruel, Baby cries.

When the early hours are creeping

And you’re wakened from your sleepirg,

If you wish to stop its weeping Dam its eyes.

A, H, M,

SHOULD auld acquaintance be forgot,

And never brought to min’?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And days o’ lang syne?

For auld lang syne, my dear,

For auld lang syne,

We’ll tak’ a cup o’ kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.

And here’s a hand, my trusty frien’,

And gie’s a hand o’ thine;

And we’ll tak’ a right gude willie-waught

For auld lang syne.

And surely ye’ll be your pint stoup,

And surely I’ll be mine!

And we’ll tak’ a cup o’ kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.

For auld lang syne, etc.

Willie-waught, draught; stoup, measure.

GOD save our gracious King,

Long live our noble King,

God save the King!

Send him victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us,

God save the King!

O Lord our God, arise,

Scatter his enemies,

And make them fall!

Confound their politics,

Frustrate their knavish tricks

On Thee our hopes we fix—

God save us all!

Thy choicest gifts in store,

On him be pleased to pour,

Long may he reign!

May he defend our laws,

And ever give us cause

To sing, with heart and voice,

God save the King.

SIR W. S. GILBERT

THE Ballyshannon foundered off the coast of Coriboo,

And down in fathoms many went the captain and his crew;

Down with the owners, greedy men, whom hope of gain allured,

Oh, dry the starting tear—for they were heavily insured!

Beside the captain and the mate, the owners and the crew,

The passengers were also drowned excepting only two—

Young Peter Grey, who tasted teas for Baker, Croop & Co.,

And Somers, who from Eastern shores imported indigo.

These passengers, by reason of their clinging to a mast,

Upon a desert island were eventually cast.

They hunted for their meals, as Alexander Selkirk used,

But they couldn’t chat together—they had not been introduced.

For Peter Grey, and Somers too, though certainly in trade,

Were properly particular about the friends they made;

And somehow, thus they settled it, without a word of mouth,

That Grey should take the northern half, while Somers took the south.

On Peter’s portion oysters grew, a delicacy rare,

But oysters were a delicacy Peter couldn’t bear.

On Somers’ side was turtle, on the shingle lying thick,

Which Somers couldn’t eat, because it always made him sick.

Grey gnashed his teeth in envy, as he saw a mighty store

Of turtle, unmolested, on his fellow-creature’s shore.

The oysters at his feet aside impatiently he shoved,

For turtle, and his mother, were the only things he loved.

And Somers sighed in sorrow, as he settled in the south,

For the thought of Peter’s oysters brought the water to his mouth.

He longed to lay him down upon the shelly bed, and stuff,

For he’d often eaten oysters, but he’d never had enough.

How they wished an introduction to each other they had had,

When on board the Ballyshannon! and it almost drove them mad

To think how very friendly with each other they might get

If it wasn’t for the arbitrary rule of etiquette.

One day when out a hunting for the mus-ridiculus,

Grey overheard his fellow-man soliloquising thus:

“I wonder how the playmates of my youth are getting on—

McConnell, S. B. Walters, Paddy Byles, and Robinson?”

These simple words made Peter as delighted as could be,

Old chummies at the Charter House were Robinson and he.

He walked straight up to Somers, then he turned extremely red,

Hesitated, hemmed and hawed, then cleared his throat and said:

“I beg your pardon—pray forgive me if I seem too bold—

But you have breathed a name I knew, familiarly of old.

You spoke aloud of Robinson—I happened to be by—

You know him?” “Yes, extremely well.” “Allow me—so do I.”

It was enough—they felt they could more pleasantly get on,

For (oh! the magic of the fact) they each knew Robinson;

And Mr. Somers’ turtle was at Peter’s service quite,

And Mr. Somers punished Peter’s oyster-bed all right.

They soon became like brothers, from community of wrongs,

They wrote each other little odes, and sang each other songs;

They told each other anecdotes—disparaging their wives—

On several occasions too, they saved each other’s lives.

They felt quite melancholy when they parted for the night,

And got up in the morning as soon as it was light.

Each other’s pleasant company they reckoned so upon,

And all because it happened they each knew Robinson.

They lived for many years on that inhospitable shore,

And day by day they learned to love each other more and more.

At last, to their astonishment, on getting up one day,

They saw a frigate anchored in the offing of the bay.

To Peter an idea occurred—“Suppose we cross the main?

So good an opportunity may not occur again.”

And Somers thought a moment, then ejaculated, “Done!

I wonder how my business in the City’s getting on?”

“But stay!” said Mr. Peter. “When in England, as you know,

I earned a living tasting teas for Baker, Croop & Co.,

I may have been suspended—my employers think me dead,”

“Then come with me,” said Somers, “and taste indigo instead.”

But all their plans were scattered in a moment, when they found

The vessel was a convict ship from Portland, outward bound.

When a boat came out to fetch them, though they felt it very kind,

To go on board they firmly and respectfully declined.

As both the happy settlers roared with laughter at the joke

They recognised a gentlemanly fellow pulling stroke;

’Twas Robinson, a convict, in an unbecoming frock,

Condemned to seven years’ for misappropriating stock.

They laughed no more, for Somers thought he had been very rash

In knowing one whose friend had misappropriated cash;

And Peter thought a foolish tack he must have gone upon,

In making the acquaintance of a friend of Robinson.

At first they didn’t quarrel very openly, I’ve heard;

They nodded when they met, and now and then exchanged a word;

The word grew rare, and rarer still the nodding of the head,

But when they meet each other now, they cut each other dead.

To allocate the Island they agreed by word of mouth,

And Peter takes the north again and Somers takes the south.

And Peter has the oysters, which he hates, in layers thick,

And Somers has the turtle, and it always makes him sick.

(By permission of Lady Gilbert.)

All Court Functions, Levees, Receptions, etc.—Special and very strict ancient regulations apply to these occasions, and it is necessary to consult one of the firms who are thoroughly acquainted with the rules and regulations.

From designs by N. T. Greenlaw & Co., by permission.

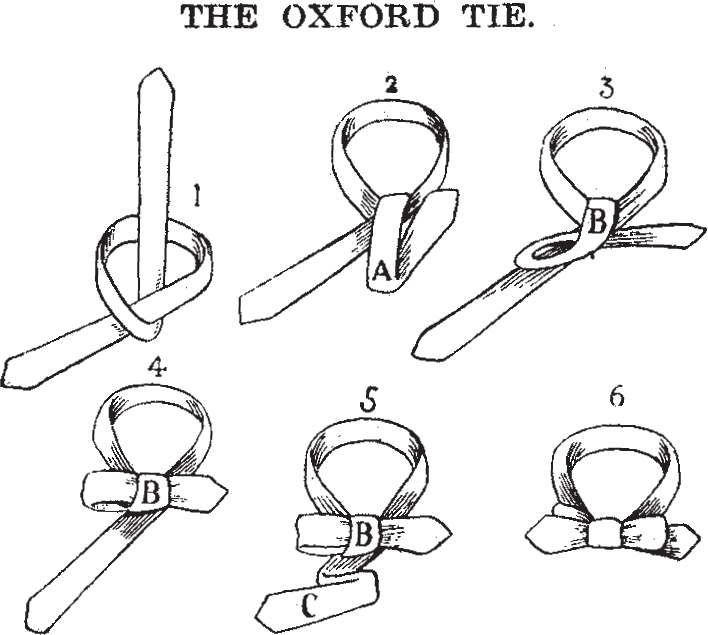

The Oxford Tie.

The diagram shows a new way of tying the Oxford Tie into a straight bow: Fold A with reversing turn to form the loop B (fig. 3 is a half turn), then fold C and pass through loop B to produce fig. 6 (fig. 4 is a complete turn).

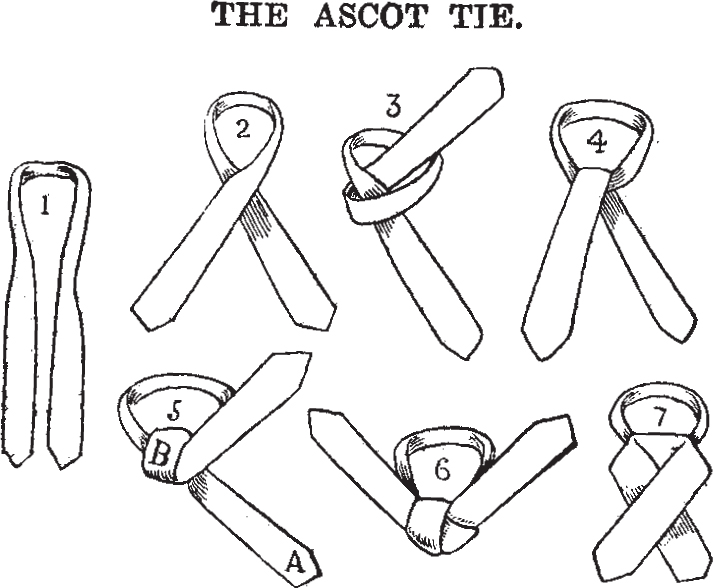

The Ascot Tie.

This diagram shows the tying of the Ascot Tie into a pin shape. The advantage of this tie is that both ends can be used in tying: Pass A through B, drop ends down to produce fig. 7, and pin is required.

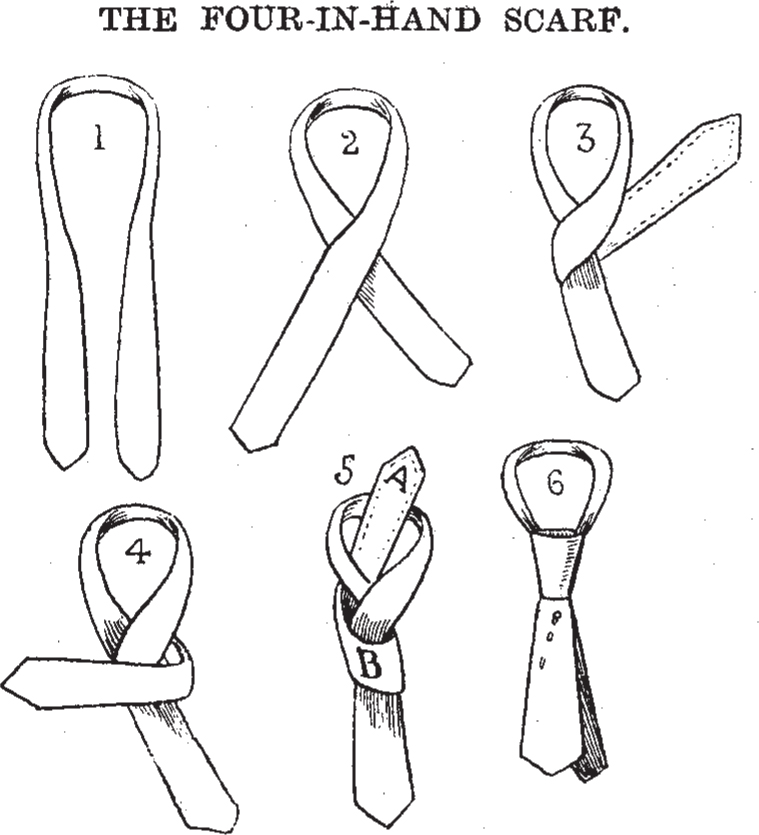

The Four-in-Hand Scarf.

The diagram shows the tying of the Four-in-Hand Scarf into a sailor’s knot: Pass A through B to produce fig.

THEIR sweet salutes are not misplaced

When women kiss a friend or brother,

But surely ’tis a wicked waste

When women kiss each other.

And yet a Christian virtue they may teach,

With greater eloquence than parsons preach,

By doing unto others as they would

That men should do to them, and that is good.

M.

“May I print a kiss on your lips?” I said,

And she nodded her sweet permission;

So we went to press, and I rather guess

We printed a big edition.—Modem Society.

HE met her in the darkened hall

And said, “I’ve brought some roses.”

Her answer seemed irrelevant,

She said, “How cold your nose is!”

Modem Society.

“You must give back,” her mother said

To the poor sobbing little maid,

“All the young man has given you,

Hard as it now may seem to do.”

“’Tis done already, mother dear,”

Said the sweet girl, “so never fear,

All the fond looks and words that passed

And all the kisses to the last.”—W. P. Landor.

The old world was a pleasant place

Before the scientist

Brought men and microbes face to face

And bade the man resist.

A pretty girl I may not kiss,

Lest evil germs escape her,

And put an end to all my bliss—

For life is but a vapour?

Though heart should fail and senses whirl,

And ’twere my final dinner,

I’d rather eat the pretty girl

And all the microbes in her.—A. H. M.

“Go ask papa,” the maiden said.

He, knowing her papa was dead,

And what a wicked life he’d led,

Quite understood her, when she said, “Go ask papa.”

Marriages are made in heaven.

Marriage and hanging go by destiny.

Two untied are drawn together,

Tie them and they strain the tether.—M.

Who woo in poetry may wed in prose,

And tragedy may bring the farce to close.—M.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments.— Shakespeare.

Wed-lock without love, they say,

Is like a lock without a key.—Butler.

Yet some have found who long have tarried,

There are worse things than getting married.—M.

They were so one that none could ever say,

Which most did rule, and which did most obey.

He ruled because she would obey, and she,

In the obeying, ruled as much as he.

He paid her compliments of yore,

And now he pays her bills,

And time runs up a pretty score,

For homely joys and ills;

But when the times are wintriest,

To show she only borrows,

She pays him back with interest

In all his joys and sorrows.

The honey-moon is very strange.

Unlike all other moons the change

She regularly undergoes:

She rises at the full; then loses

Much of her brightness; then reposes

Faintly; and then . . . has naught to lose.

W. S. Landor.

All moons for ever wax and wane,

Who will, may watch, nor watch in vain,

The faintest round to full again.—M.

A hundred times I softly sighed,

“Be mine, dear maid, be mine,”

Ere she consented. Now I wish

I’d stopped at ninety-nine.—W. Thomson.

I loved thee, beautiful and kind,

And plighted an eternal vow;

So altered are thy face and mind,

’Twere perjury to love thee now.

Lord Nugent.

When man and wife at odds fall out,

Let syntax be your tutor:

’Twixt masculine and feminine

What should we be but neuter?

“How like is my picture, the pose of the head,

The life, the expression, the spirit!

It wants but a tongue!” “Oh no, dear,” he said,

“That want is its principal merit.”

Brown lisps, and says that for a whole long

He has not spoken to his lady “wonth.” [month

“A bear,” you call him? Nay, not so abrupt, sir,

He’s too polite-he will not interrupt her.—M.

“My love, you never kiss me

Unless you want some money;

It seems that you in this be

Much like the bee and honey.”

“But surely, darling, that’s no cause for huff,

You ought to find my kisses quantum suff.

Am I not wanting money oft enough?”—M.

“My dear, what makes you always yawn?”

The wife exclaimed, her temper gone.

“Is home so dull and dreary?”

“Not so, my love,” he said, “not so,

But man and wife are one, you know,

And when alone I’m weary.”

“Come hither, Sir John, my picture is here,

What say you, my love, does it strike you?”

“I can’t say it does, just at present, my dear,

But I think it soon will, it’s so like you.”

“Lo! here’s the bride and there’s the tree,

Take which of these best liketh thee.”

“The bargain’s bad on either part,

But, hangman, come, drive on the cart.”

Who of the maidens I have seen

Should I the last importune?

Though the most constant-she has been Miss Fortune.

What dame—were I to challenge Fate

By marrying another—

Should I with least misgiving mate—

Her mother?—M.

They may talk as they please about what they call pelf,

And how one ought never to think of oneself,

How pleasures of thought surpass eating and drinking;

My pleasure of thought is the pleasure of thinking.

How pleasant it is to have money, heigh-ho!

So pleasant it is to have money.

It’s all very well to be handsome and tall,

Which certainly makes you look well at a ball;

It’s all very well to be clever and witty,

But if you are poor, why it’s only a pity.

So needful it is to have money, heigh-ho,!

So needful it is to have money.

There’s something undoubtedly in a fine air,

To know how to smile and be able to stare;

High breeding is something, but well-bred or not,

In the end the one question is, what have you got?

So needful it is to have money, heigh-ho!

So needful it is to have money.

A. H. Glough.

Good Luck is the gayest of all gay girls;

Long in one place she will not stay:

Back from your brow she strokes the curls,

Kisses you quick and flies away.

But Madame Bad Luck soberly comes

And stays—no fancy has she for flitting—

Snatches of true-love songs she hums,

And sits by your bed, and brings her knitting.—John Hay

It’s when a man would borrow

That he is brought to see,

And find out, to his sorrow,

How close a friend can be.—Anon.

His velvet-like paws hide his talons of steel,

He smiles as he thinks how you’ll break on his wheel;

He’ll smile at your wit and he’ll humour your bent,

The price of his friendship three hundred per cent.

“He owned a million yesterday,”

They said—said one who’d known him:

“Was ever millionaire could say

His money didn’t own him?

A self-made man who boasts his own ability

Relieves God of a great responsibility.

Once I pictured, fondly yearning,

All the gay and merry sport

That would greet my ship returning Into port.

Now I crow a very low note,

And ’twill be a modest din

That will greet my little row-boat Coming in.

“Life is short!” the preacher cried

From the pulpit up on high.

Jameson heard and softly sighed:

“True! ah, true! And so am I.”

“Life is real!” the preacher said.

Jameson nodded. Vain regrets!

Bowed in patience he his head,

“So,” he sighed, “are all my debts.”

“Life is earnest!” next he heard.

Cold sweat oozed through all his pores.

“Yes,” he whispered, “that’s the word;

So are all my creditors.”—Tribune.

A hope fulfilled in perfect bliss

Has been of many a tale the text;

How false of life, unless it is

“To be continued in our next.”

(Reprinted, by permission, from the Revised Oode, 1900.)

CARDS

1. Two packs of cards are used, one being used by each side.

2. A card or cards torn or marked must be either replaced by agreement, or new cards called for at the expense of the table.

3. Any player, before the pack is cut for the deal, may call for fresh cards on paying for them. He must call for two new packs, of which the dealer takes his choice.

CUTTING OR DRAWING

4. The ace is the lowest card in cutting or drawing.

5. In all cases, every one must cut or draw from the same pack.

6. Should a player expose or draw more than one card, he must cut or draw again.

FORMATION OR TABLE

7. (a) The candidates first in the room have the preference. When there are more than six candidates, and there is a doubt or question as to the preference of two or more of them, they determine their preference by drawing. Those drawing the lower cards have the preference. The table is complete with six players. On the retirement of any of those six players, the candidates who, in the first draw, drew the lowest cards have the prior right to enter the table.

(b) If there are more than four players they all draw, and the four who draw the lowest cards play first.

(c) When two or more candidates or players draw cards of equal value they draw again, if necessary, to determine their precedence.

PARTNERS

8. The four who play first again draw to decide on partners. The two lowest play against the two highest. The lowest is the dealer and has choice of cards and seats, and, having once made his selection, must abide by it.

9. Two players drawing cards of equal value, which are not the two highest, draw again. If the equal cards are not the two lowest, the higher in the new draw plays with the highest in the original draw; if the equal cards are the two lowest, the new draw decides who is to deal.1

10. Three players drawing cards of equal value draw again; should the fourth (or remaining) card be the highest in the original draw, the two lowest of the new draw are partners, the lower of those two the dealer; should the fourth card be the lowest, the two highest are partners, the original lowest the dealer.2

1 Example. A three, two sixes, and a knave are drawn. The two sixes draw again, and the lower plays with the three. Suppose, at the second draw, the two sixes draw a king and a queen, the queen plays with the three.

If at the second draw, a lower card than the three is drawn the three still retains its privileges as original low, and has the deal and choice of cards and seats.

2 Example. Three aces and a two are drawn. The three aces draw again. The two is the original high, and plays with the highest of the next draw.

Suppose, at the second draw, two more twos and a king are drawn. The king plays with the original two, and the other pair of twos draw again for deal.

Suppose, instead, the second draw to consist of an ace and two knaves. The two knaves draw again, and the higher plays with the two.

CUTTING OUT

11. At the end of a rubber, should admission be claimed by any one, or by two candidates, he who has, or they who have, played a greater number of consecutive rubbers than the other is, or are, out; but when two or more have played the same number, they must, when necessary, cut or draw to decide upon the out-goers; the highest are out.

ENTRY AND RE-ENTRY

12. A candidate wishing to enter a table must declare such intention prior to any of the players having drawn a card, either for the purpose of commencing a fresh rubber or of cutting out.

12 a. Any candidate may declare into any table that is not complete. If he do so he shall have priority over any candidate who has not previously declared in.

13. In the formation of fresh tables, those candidates who have not played at any other table have the prior right of entry; the others decide their right of admission by drawing.

14. Any one quitting a table prior to the conclusion of a rubber may, with consent of the other three players, appoint a substitute in his absence during that rubber.

15. A player cutting into one table, whilst belonging to another, loses his prior right of re-entry into that latter, and takes his chance of cutting in, as if he were a fresh candidate, and last in the room.

16. If any one break up a table, the remaining players have the prior right to him of entry into any other, and should there not be sufficient vacancies at such other table to admit all those candidates, they settle their precedence by drawing.

SHUFFLING

17. After the selection of cards for the first deal has been made, it is the duty of an adversary to shuffle the pack selected, and of the player who is about to deal, or of his partner, to shuffle the other pack.

18. The pack must neither be shuffled below the table, nor so that the face of any card be seen.

19. The pack must not be shuffled during the play of the hand.

20. A pack, having been played with, must not be shuffled by dealing it into packets.

21. Each player has a right to shuffle once only, except as provided by Law 24, prior to a deal, after a false cut,1 or prior to a new deal.2

22. The dealer’s partner must collect the cards for the ensuing deal, and has the first right to shuffle that pack.

23. Each player, after shuffling, must place the cards, properly collected and face downwards, to the left of the player about to deal them.

24. The dealer has always the right to shuffle last. Should a card or cards be seen during his shuffling or whilst giving the pack to be cut, he may be compelled to re-shuffle.

| Vide Law 26. | 2 Vide Law 29. |

THE DEAL

25. The deal commences with the player who cut the original lowest card, the next deal falls to the player on his left, and so on until the rubber is finished.

26. When the pack has been finally shuffled, the player about to deal shall present it to the adversary on his right, who shall cut it, and in dividing it, must not leave fewer than four cards in either packet; if in cutting, or in replacing one of the two packets on the other, a card be exposed,1 or if there be any confusion of the cards, or a doubt as to the exact place in which the pack was divided, there must be a fresh cut.

27. When the player whose duty it is to cut has once separated the pack, he cannot alter his intentions; he can neither re-shuffle nor re-cut the cards.

28. When the pack is cut, should the dealer shuffle the cards, he loses his deal.

29. There must be a new deal by the same dealer2—

I. If, during a deal, or during the play of a hand, the pack be proved incorrect or imperfect.

II. If any card, excepting the last, be faced in the pack.

III. If a player takes up another player’s hand.

30. If, whilst dealing, a card be exposed on or below the table by the dealer or his partner, should neither of the adversaries have touched the cards, the latter can claim a new deal; a card exposed by either adversary gives that claim to the dealer, provided that his partner has not touched a card; if a new deal does not take place, the exposed card cannot be called.

31. If, during dealing, a player touch any of his cards, the adversaries may do the same, without losing their privilege of claiming a new deal, should chance give them such option.

32. If, in dealing, one of the cards be exposed, and the dealer turn up the trump before there is reasonable time for his adversaries to decide as to a fresh deal, they do not thereby lose their privilege.

33. If a player, whilst dealing, look at the trump card, his adversaries have a right to see it, and either may exact a new deal.

34. Any one dealing out of turn, or with the adversary’s cards, may be stopped before the trump card is turned up, after which the game must proceed as if no mistake had been made.

35. A player can neither shuffle, cut, nor deal for his partner, without the permission of his opponents.

36. If the adversaries interrupt a dealer whilst dealing, either by questioning the score or asserting that it is not his deal, and fail to establish such claim, should a misdeal occur, he may deal again,

1 After the two packets have been re-united, Law 30 comes into operation.

2 Vide also Laws 36 and 41.

A MISDEAL

37. It is a misdeal1—

I. Unless the cards are dealt into four packets, one at a time in regular rotation, beginning with the player to the dealer’s left.

II. Should the dealer place the last (which is called the trump) card, face downwards, on his own or on any other packet.

III. Should the trump card not come in its regular order to the dealer; but he does not lose his deal if the pack be proved imperfect.

IV. Should a player have fourteen or more cards, and any of the other three less than thirteen; 2 unless the excess has arisen through the act of an adversary, in which case there must be a fresh deal.

V. Should the dealer touch, for the purpose of counting, the cards on the table or the remainder of the pack.

VI. Should the dealer deal two cards at once, or two cards to the same hand, and then deal a third; but if, prior to dealing that third card, the dealer can, by altering the position of one card only, rectify such error, he may do so, except as provided by the second paragraph of this Law.

VII. Should the dealer omit to have the pack cut to him, and the adversaries discover the error, prior to the trump card being turned up, and before looking at their cards, but not after having done so.

38. Should a player take his partner’s deal, and misdeal, the latter is liable to the usual penalty, and the adversary next in rotation to the player who ought to have dealt then deals.

39. A misdeal loses the deal;1 unless, during the dealing, either of the adversaries touch the cards prior to the dealer’s partner having done so; but should the latter have first interfered with the cards, notwithstanding either or both of the adversaries have subsequently done the same, the deal is lost.

40. Should three players have their right number of cards-the fourth have less than thirteen, and not discover such deficiency until the first trick has been turned and quitted, the pack shall be assumed to be complete, and the deal stands good; and he will be answerable for any revoke he may have made, in the same way as if the missing card or cards had been in his hand.

41. If a pack, during or after a rubber, be proved incorrect or imperfect, such proof does not alter any past score, game, or rubber; that hand in which the imperfection was detected is null and void (except in the case of such deficiency as is provided for by Law 40); the dealer deals again.

1 Vide also Law 28.

2 The pack being perfect. Vide Law 41.

THE TRUMP CARD

42. The dealer, when it is his turn to play to the first trick, should take the trump card into his hand; if left on the table after the second trick be turned and quitted, it is liable to be called.2 His partner may at any time remind him of the liability.

43. After the dealer has taken the trump card into his hand, it must not be asked for; a player naming it at any time during the play of that hand is liable to have his highest or lowest trump called. Such call cannot be repeated. Any player may at any time inquire what the trump suit is.

44. If the dealer take the trump card into his hand before it is his turn to play, he may be desired to lay it on the table; should he show a wrong card, this card may be called, as also a second, a third, etc., until the trump card be produced.

45. If the dealer declare himself unable to recollect the trump card, his highest or lowest trump may be called at any time during that hand, and, unless it cause him to revoke, must be played; the call may be repeated, but not changed (i.e. from highest to lowest, or vice versa) until such card is played.

l Except as provided in Law 36.

2 It is not usual to call the trump card if left on the table.

THE RUBBER

46. The rubber is the best of three games. If the first two games be won by the same players, the third game is not played.

SCORING

47. A game consists of five points. Each trick, above six, counts one point.

48. Honours, i.e. Ace, King, Queen, and Knave of trumps, are thus reckoned:

If a player and his partner, either separately or conjointly, hold—

I. The four honours, they score four points.

II. Any three honours, they score two points,

49. Those players who, at the commencement of a deal, are at the score of four, cannot score honours.

50. The penalty for a revoke1 takes precedence of all other scores. Tricks score next. Honours last.

51. Honours, unless claimed before the trump card of the following deal is turned up, cannot be scored.

52. To score honours is not sufficient; they, must be claimed at the end of the hand; if so claimed, they may be scored at any time during the game. If the tricks won, added to honours held, suffice to make game, it is sufficient to call game.

53. The winners gain—

I. A treble, or game of three points, when their adversaries have not scored.

II. A double, or game of two points, when their adversaries have scored one or two.

III. A single, or game of one point, when their adversaries have scored three or four.

54. The winners of the rubber gain two points (commonly called the rubber points) in addition to the value of their games.

55. Should the rubber have consisted of three games, the value of the losers’ game is deducted from the gross number of points gained by their opponents.

56. If an erroneous score be proved, such mistake can be corrected prior to the conclusion of the game in which it occurred, and such game is not concluded until the trump card of the following deal has been turned up.

57. If an erroneous score, affecting the value of the rubber,1 be proved, such mistake can be rectified at any time during the rubber.

1 Vide Law 75.

CARDS LIABLE TO BE CALLED

58. The following are exposed cards:—

I. Two or more cards played at once, face upwards.

II. Any card dropped with its face upwards, in any way on or above the table, even though snatched up so quickly that no one can name it.

III. Every card named by the player holding it.

59. All exposedcards are liable to be called, and must be left or placed face upwards on the table. If two or more cards are played at once, the adversaries have a right to call which they please to the trick in course of play, and afterwards to call the remainder. A card is not an exposed card, under the preceding Law, when dropped on the floor, or elsewhere below the table. An adversary may not require any exposed card to be played before it is the turn of the owner of the card to play; should he do so, he loses his right to exact the penalty for that trick.

60. If any one play to an imperfect trick the winning card on the table, and then lead without waiting for his partner to play, or lead one which is a winning card as against his adversaries, and then lead again, without waiting for his partner to play, or play several such winning cards, one after the other, without waiting for his partner to play, the latter may be called on to win, if he can, the first or any other of those tricks, and the subsequent cards thus improperly played are exposed cards.

61. If a player or players (not being all) throw his or their cards on the table face upwards, such cards are exposed, and liable to be called, each player’s by the adversary; but no player who retains his hand can be forced to abandon it.

62. If all four players throw their cards on the table face upwards, the hands are abandoned; and no one can again take up his cards. Should this general exhibition show that the game might have been saved or won by the losers, neither claim can be entertained unless a revoke be established. The revoking players are then liable to the following penalties: they cannot under any circumstances win the game by the result of that hand, and the adversaries may add three to their score, or deduct three from that of the revoking players, for each revoke.

63. If a card be detached from the rest of the hand, which an adversary at once correctly names, such card becomes an exposed card; but should, the adversary name a wrong card, he is liable to have a suit called when he or his partner next have the lead.

64. If any player lead out of turn, his adversaries may either call the card erroneously led, or may call a suit from him or his partner when it is next the turn of either of them to lead. The penalty of calling a suit must be exacted from whichever of them next first obtains the lead. It follows that if the player, who leads out of turn is the partner of the person who ought to have led, and a suit is called, it must be called at once from the right leader. If he is allowed to play as he pleases, the only penalty that remains is to call the card erroneously led. The fact that the card erroneously led has been played without having been called, does not deprive the adversaries of their right to call a suit. If a suit is called, the card erroneously led may be replaced in the owner’s hand.

65. If it is one, player’s lead, and he and his partner lead simultaneously, the penalty of calling the highest or lowest card of the suit properly led may be exacted from the player in error, or the card simultaneously led may be treated as a card liable to be called.

66. If any player lead out of turn, and the other three have followed him, the trick is complete, and the error cannot be rectified; but if only the second, or the second and third, have played to the false lead, their cards, on discovery of the mistake, are taken back; there is no penalty against any one, excepting the original offender, whose card may be called—or he, or his partner (whichever of them next first has the lead), may be compelled to play any suit demanded by the adversaries.

67. In no case can a player be compelled to play a card which would oblige him to revoke.

68. The call of a card may be repeated at every trick, until such card has been played.

69. If a player called on to lead a suit have none of it, the penalty is paid.

1 E.g. If a single is scored by mistake for a double or treble, or vice versa.

IRREGULAR PLAY

70. If the third hand play before the second, the fourth hand may play before his partner.

71. Should the third hand not have played, and the fourth play before his partner, the latter may be called on to win or not to win the trick.

72. If any one omit playing to a trick, and such error be not discovered until he has played to the next, the adversaries may claim a new deal; should they decide that the deal stand good, the surplus card at the end of the hand is considered to have been played to the imperfect trick, but does not constitute a revoke therein.

73. If any one play two cards to the same trick, or mix his trump, or other card, with a trick to which it does not properly belong, and the mistake be not discovered until the hand is played out, he is answerable for all consequent revokes he may have made.1 If, during the play of the hand, the error be detected, the tricks may be counted face downwards, in order to ascertain whether there be among them a card too many; should this be the case they may be searched, and the card restored; the player is, however, liable for all revokes which he may have meanwhile made. If no revoke has been made, the card can be treated as an exposed card.

Vide also Law 40

THE REVOKE

74. It is a revoke when a player, holding one or more cards of the suit led, plays a card of a different suit.

75. The penalty for a revoke—

I. Is at the option of the adversaries, who, at the end of the hand, may either take three tricks from the revoking player and add them to their own tricks, or deduct three points from his score, or add three to their own score (the adversaries may consult as to which penalty they will exact);

II. Can be claimed for as many revokes as occur during the hand, and a different penalty may be exacted for each revoke;

III. Is applicable only to the score of the game in which it occurs;

IV. Cannot be divided, i.e. a player cannot add one or two to his own score, and deduct one or two from the revoking player;

V. Takes precedence of every other score—e.g. The claimants two—their opponents nothing—the former add three to their score—and thereby win a treble game, even should the latter have made thirteen tricks, and held four honours.

76. If a player who has become liable to have the highest or lowest of a suit called, or to win or not to win a trick (when able to do so), fail to play as desired, or if a player, when called on to lead one suit, lead another, having in his hand one or more cards of that suit demanded, he incurs the penalty of a revoke.