4 SOCIAL FITNESS Keeping Your Relationships in Good Shape

A sad soul can kill you quicker, far quicker, than a germ.

John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley

Harvard Study Second Generation Interview, 2016

Q: Your father participated in the Harvard Study. Looking back on his life, is there anything you learned from him?

A: Dad worked very hard and he was a great engineer but he had a hard time expressing his feelings or even knowing his feelings, so he worked because he didn’t know what to do. He played tennis and had friends, but his marriage fell apart, and he tried it with another woman at 66 and it didn’t work out. He was 80 and when he died he was alone. And I feel bad for him. I imagine that was true for others of his generation.

Vera Eddings, Second Generation participant, age 55

Psychology often studies the effects of emotional wounds. But we want to talk about one particular study that began by creating wounds. Physical ones.

It’s not as bad as it sounds; participants had a piece of their skin the size of a pencil eraser removed from their arms just above the elbow, in a procedure known as a punch biopsy. This is a common medical procedure normally used to remove and examine a small piece of skin, but this study was interested not in what was removed but in what was left behind—the wound.

The lead researcher, Janice Kiecolt-Glaser, was investigating psychological stress. She already knew from past research that stress affected the immune system. What she wanted to find out was whether that stress affected other body processes, such as how physical wounds heal.

She sampled two groups of women. The first were the primary caregivers for loved ones with dementia. The second was a group, roughly the same age (early 60s), who were not caregivers.

The study itself was very simple. She performed a punch biopsy on all of the participants, and then watched the wounds heal.

The results were startling. The wounds of the noncaregivers took about forty days to fully heal, but the wounds of the caregivers took nine days longer to heal. The psychological stress of caring for a loved one, which emerged from the slow erasure of important relationships in their lives, was preventing their bodies from healing.

Many years later, Kiecolt-Glaser found herself in the same situation, when her husband and closest research collaborator, Ronald Glaser, developed fast-progressing Alzheimer’s disease. When her internist asked her how she was feeling during a regular check-up, Kiecolt-Glaser said she was feeling stressed, and talked about her husband. The internist told her to take care of herself and mentioned that there was now research about stress and health in caregivers—research that Kiecolt-Glaser herself had pioneered. The science had succeeded in making its way into medicine, and back to the source.

THE MIND IS THE BODY IS THE MIND

There is no longer any doubt that the mind and the body are intertwined. When a new emotional or physical stimulus is encountered, the entire mind-body system is affected—sometimes in minuscule ways, sometimes in massive ways—and the changes can have a cyclical effect, with the mind affecting the body, which then affects the mind, and so on.

Modern society, though more medically advanced than ever before, encourages some habits and routines that are not healthy for body or mind. Let’s take just one: lack of exercise.

Fifty thousand years ago a Homo sapiens living in a river settlement with her tribe would have gotten the physical exercise she needed simply through the effort of staying alive. Now vast numbers of people are able to provide food, shelter, and safety for themselves with little or no physical exercise. Never before has so much human life taken place in a seated position, and a great deal of the physical work we do is repetitive and potentially damaging. Our bodies do not take care of themselves in this environment—they need maintenance. If those of us in sedentary or repetitive jobs want to maintain our physical fitness, we have to make a conscious effort to move. We have to set time aside to walk, garden, do yoga, run, or go to the gym. We have to overcome the currents of modern life.

The same is true for social fitness.

It’s not easy to take care of our relationships today, and in fact, we tend to think that once we establish friendships and intimate relationships, they will take care of themselves. But like muscles, neglected relationships atrophy. Our social life is a living system. And it needs exercise.

You don’t have to examine scientific findings to recognize that relationships affect you physically. All you have to do is notice the invigoration you feel when you believe someone has really understood you during a good conversation, or notice the tension and distress after an argument, or the lack of sleep during a period of romantic strife.

Knowing how to improve our social fitness, however, isn’t easy. Unlike stepping on the scale, taking a quick look in the mirror, or getting readouts for blood pressure and cholesterol, assessing our social fitness requires a bit more sustained self-reflection. A much deeper look in the mirror. It requires stepping back from the crush of modern life, taking stock of our relationships, and being honest with ourselves about where we’re devoting our time and whether we are tending to the connections that help us thrive. It can be hard to find the time for this type of reflection, and sometimes it’s uncomfortable. But it can yield enormous benefit.

Many of our Harvard Study participants have told us that filling out questionnaires every two years and being interviewed regularly has given them a welcome perspective on their lives and relationships. We ask them to really think about themselves and the people they love, and that process helps some of them. But as we’ve mentioned, this benefit to them is incidental—a side effect. They have volunteered for research, and our primary focus is learning about their lives. As we move through this chapter, we’ll help you develop your own mini–Harvard Study. We’ve boiled down many of the most useful questions we’ve asked Study participants into tools that you can use to develop a picture of your social fitness. Unlike the actual Harvard Study, these are not designed to gather information for research. Here, the entire point is to give you the benefit of self-reflection that our Study members received throughout their lives. We began that process in Chapter Three, and this is a chance to go a little bit further.

Looking in the mirror and thinking honestly about where your life stands is a first step in trying to live a good life. Noticing where you are can help put into relief where you would like to be. It’s understandable if you have some reservations about this kind of self-reflection. Our Study participants were not always keen on filling out our questionnaires, or eager to consider the larger picture of their lives. (Recall Henry’s reluctance to answer the question about his biggest fear.) Some would skip difficult questions, leave entire pages blank, and some would just not return certain surveys. Some even wrote comments in the margins of their questionnaires about what they thought of our requests. “What kinds of questions are these!?” is a response we received occasionally, often from participants who preferred not to think about difficulties in their lives. The experiences of the people who skipped questions or entire questionnaires were also important, though, just as crucial in understanding adult development as the experiences of people eager to share. A lot of useful data and gems of experience were buried in the shadowed corners of their lives. We just had to go through a little extra effort to dig it all out.

One of these people was Sterling Ainsley.

OUR MAN IN MONTANA

Sterling Ainsley was a hopeful guy. A materials scientist, he retired at 63 and thought of his future as bright. As soon as he left his job, he started pursuing personal interests, taking real estate courses and studying Italian on tape. He had business ideas as well, and he began reading entrepreneurial magazines for ideas that fit his interest. When asked to describe his philosophy for getting through hard times, he said, “You try not to let life get to you. You remember your victories and take a positive attitude.”

The year was 1986. Our predecessor, George Vaillant, was on a long interview trek, driving through the Rocky Mountains, visiting the Study participants who lived in Colorado, Utah, Idaho, and Montana. Sterling had not returned the most recent survey, and there was some catching up to do. He met George at a hotel in Butte, Montana, to give him a ride to the diner where Sterling wanted to do his scheduled interview (he preferred not to do it in his home). When George buckled himself into the passenger seat of Sterling’s car, the seatbelt left a stripe of dust across his chest. “I was left to wonder,” he wrote, “the last time somebody had used it.”

Sterling had graduated from Harvard in 1944. After college he’d served in the Navy during World War II and then he’d married, moved to Montana, and had three children. For the next forty years he worked on and off in metals manufacturing for various companies across the American West. Now he was 64 and lived on a 50' x 100' grass lot near Butte in a trailer that he could pull behind a truck. He liked having the grass because mowing it was his main form of exercise. He also tended a garden with an enormous patch of strawberries and what he called “the biggest peas you ever saw.” He lived in a trailer, he said, because it cost him only $35 a month for hookups, and he didn’t feel too committed to the place.

Sterling was still technically married, but his wife lived over ninety miles away in Bozeman, and they hadn’t slept in the same room in fifteen years. They spoke only every few months.

When asked why they had not gotten a divorce, he said, “I wouldn’t want to do that to the children,” even though his son and two daughters were grown and had children of their own. Sterling was proud of his kids and beamed when he spoke of them—his oldest daughter owned a framing shop, his son was a carpenter, and his youngest daughter was a cellist for an orchestra in Naples, Italy. He said his kids were the most important thing in his life, but he seemed to prefer to keep his relationships with them thriving mostly in his imagination. He rarely saw them. George noted that Sterling seemed to be using optimism to push away some of his fears and avoid challenges in his life. Putting a positive spin on every matter and then pushing it out of his mind made it possible for him to believe that nothing was wrong, that he was fine, he was happy, his kids didn’t need him.

The previous year his youngest daughter had invited him to visit her in Italy. He decided not to go. “I don’t want to be a burden,” he said, although he had been learning Italian specifically for that purpose.

His son lived only a few hours away, but they hadn’t seen each other in more than a year. “I don’t go down there,” he said. “I telephone him.”

When asked about his grandchildren he said, “I’ve not gotten too involved with them.” They were doing great without him.

Who was his oldest friend?

“Gosh, so many of them died,” he said. “So many of them die. I hate to get attached. It hurts too much.” He said he had an old pal from out east but hadn’t talked to him in years.

Any work friends?

“My friends at work retired. We were good buddies, but they moved away.” He talked about his involvement in the VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) and the fact he moved up to district commander at one point, but he stepped down in 1968. “It takes a lot out of you.”

When did he last talk to his older sister, and how was she doing?

Sterling seemed startled by this question. “My sister?” he said. “You mean Rosalie?”

Yes, the sister he told the Study so much about when he was younger.

Sterling thought about it for a long time, and then told George that it must have been twenty years ago that he last spoke to her. A frightened expression came over his face. “Would she still be living?” he said.

Sterling tried not to think about his relationships, and he was even less inclined to talk about them. This is a common experience. We don’t always know why we do things or why we don’t do things, and we may not understand what is holding us at a distance from the people in our lives. Taking some time to look in the mirror can help. Sometimes there are needs inside of us that are looking for a voice, a way to get out. They might be things that we have never seen, nor articulated to ourselves.

This seemed to be the case with Sterling. Asked how he spent his evenings, he said he watched TV with an 87-year-old woman who lived in a nearby trailer. Each night he would walk over, and they’d watch TV and talk. Eventually she would fall asleep, and he would help her into bed and wash her dishes and close the shades before walking home. She was the closest thing he had to a confidant.

“I don’t know what I’ll do if she dies,” he said.

LONELINESS HURTS

When you’re lonely, it hurts. And we don’t mean that metaphorically. It has a physical effect on the body. Loneliness is associated with being more sensitive to pain, suppression of the immune system, diminished brain function, and less effective sleep, making an already lonely person even more tired and irritable. Recent research has shown that for older people loneliness is twice as unhealthy as obesity, and chronic loneliness increases a person’s odds of death in any given year by 26 percent. A study in the U.K., the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, recently reported on the connections between loneliness and poorer health and self-care in young adults. This ongoing study includes more than 2,200 people born in England and Wales in 1994 and 1995. When they were 18, the researchers asked them how lonely they were. Those who reported being lonelier were more likely to experience mental health problems, to engage in risky physical health behaviors, and to use more negative strategies to cope with stress. Add to this the fact that a tide of loneliness is flooding through modern societies, and we have a serious problem. Recent stats should make us take notice.

In a study conducted online that sampled 55,000 respondents from across the world, one out of every three people of all ages reported that they often feel lonely. Among these, the loneliest group were 16–24-year-olds, 40 percent of whom reported feeling lonely “often or very often” (more on this phenomenon soon). In the U.K., the economic cost of this loneliness—because lonely people are less productive and more prone to employment turnover—is estimated at more than £2.5 billion (about $3.4 billion) annually and helped lead to the establishment of a U.K. Ministry of Loneliness.

In Japan, 32 percent of adults surveyed before 2020 expected to feel lonely most of the time in the coming year.

In the United States, a 2018 study suggested that three out of four adults felt moderate to high levels of loneliness. As of this writing, the long-term effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, which separated us from each other on a massive scale and left many feeling more isolated than ever, are still being studied. In 2020 it was estimated that 162,000 deaths could be attributed to causes stemming from social isolation.

Alleviating this epidemic of loneliness is difficult because what makes one person feel lonely might have no effect on someone else. We can’t rely entirely on easily observed indicators like whether or not one lives alone, because loneliness is a subjective experience. One person might have a significant other and too many friends to count and yet feel lonely, while another person might live alone and have a few close contacts, and yet feel very connected. The objective facts of a person’s life are not enough to explain why someone is lonely. Regardless of your race or class or gender, the feeling resides in the difference between the kind of social contact you want and the social contact you actually have. But, then, how can loneliness be so physically harmful when it’s a subjective experience?

Answering that question is a bit easier if we understand the biological roots of the problem. As we discussed in Chapter Two, human beings have evolved to be social. The biological processes that encourage social behavior are there to protect us, not to harm us. When we feel isolated, our bodies and brains react in ways that are designed to help us survive that isolation. Fifty thousand years ago, being alone was dangerous. If the Homo sapiens we mentioned earlier was left at her tribe’s river settlement by herself, her body and brain would have gone into temporary survival mode. The need to recognize threats would have fallen on her alone, and her stress hormones would have increased and made her more alert. If her family or tribe were away overnight and she had to sleep by herself, her sleep would have been shallower; if a predator was approaching, she would want to know, so she would have been more easily aroused, and she would have experienced more awakenings in the night.

If for some reason she found herself alone for say, a month, rather than a night, these physical processes would continue, morphing into a droning, constant sense of unease, and they would begin to take a toll on her mental and physical health. She would be, as we say, stressed out. She would be lonely.

The same effects of loneliness continue today. The feeling of loneliness is a kind of alarm ringing inside the body. At first, its signals may help us. We need them to alert us to a problem. But imagine living in your house with a fire alarm going off all day, every day, and you start to get a sense of what chronic loneliness is doing behind the scenes to our minds and bodies.

Loneliness is only one piece of the mind-body equation of relationships. It is the visible tip of the social iceberg; much more is submerged beneath the surface. There is now a vast body of research revealing the associations between health and social connection, associations that trace back to the origins of the species, when things were much simpler. Our basic relationship needs are not complicated. We need love, connection, and a feeling of belonging. But we now live in complicated social environments, so how we meet those needs is the challenge.

LIFE BY THE NUMBERS

Think for a moment about a relationship you have with a person you cherish but feel like you don’t see nearly enough. This needn’t be your most significant relationship, just someone who makes you feel energized when you’re with them, and who you’d like to see more often. Run through the possible candidates (there may only be one!) and get this person in mind. Now think about the last time you were together and try to re-create in your imagination how they made you feel at the time. Were you optimistic, feeling almost invincible? Did you feel understood? Maybe you were quick to laugh, and the ills in your life and the world felt less daunting.

Now think about how often you see that person. Every day? Once a month? Once a year? Do the math and project how many hours in a single year you think you spend with this person. Write this number down and hang on to it.

For us, Bob and Marc, though we meet up every week by phone or video call, we see each other in person only for a total of about two days (forty-eight hours) every year.

How does this add up for the coming years? When this book comes out, Bob will be 71 years old. Marc will be 60. Let’s be (very) generous and say we are both around to celebrate Bob’s 100th birthday. At two days per year for twenty-nine years, that’s fifty-eight days that we have left to spend together in our lifetimes.

Fifty-eight out of 10,585 days.

Of course, this is assuming a lot of good fortune, and the real number is almost certainly going to be lower.

Try this calculation with your own cherished relationship, or just consider these round numbers: If you’re 40, and you see this person once a week for a coffee hour, that’s about eighty-seven days before you turn 80. If you see them once a month, it’s about twenty days. Once a year, about two days.

Maybe these numbers sound like plenty. But contrast them with the fact that in 2018, the average American spent an astonishing eleven hours every day interacting with media, from television to radio to smartphones. From the age of 40 to the age of 80, that adds up to eighteen years of waking life. For someone who is 18, that’s twenty-eight years of life before they turn 80.

The point of this mental exercise is not to alarm you. It’s to bring clarity to something that goes largely unnoticed: how much time we actually spend with the people we like and love. We don’t need to be with all of our good friends all the time. In fact, some people who energize us and enhance our lives might do so specifically because we don’t see them very often, and like anything else in life, there is a balance that should be struck. Sometimes we are compatible with a person only to a point, and that point is good enough.

But most of us have friends and relatives who energize us and who we don’t see enough. Are you spending time with the people you most care about? Is there a relationship in your life that would benefit both of you if you could spend more time together? These untapped resources are often already in our life, waiting. A few adjustments to our most treasured relationships can have real effects on how we feel, and on how we feel about our lives. We might be sitting on a goldmine of vitality that we are not paying attention to—because this source of vitality is eclipsed by the shiny allure of smartphones and TV or pushed to the side by work demands.

TWO CRUCIAL PREDICTORS OF HAPPINESS

In 2008 we telephoned the wives and husbands of Harvard Study couples in their 80s every night for eight nights. We spoke to each partner separately and asked them a series of questions about their days. We mentioned these surveys in Chapter One (they generated a lot of useful data!). We wanted to know how they’d felt physically that day, what kinds of activities they’d been involved in, if they’d needed or received emotional support, and how much time they’d spent with their spouse and with other people.

The simple measure of time spent with others proved quite important, because on a day-to-day basis this measurement was clearly linked with happiness. On days when these men and women spent more time in the company of others, they were happier. In particular, the more time they spent with their partners, the more happiness they reported. This was true across all couples but especially true for those in satisfying relationships.

Like most older folks, these men and women experienced day-to-day fluctuations in their levels of physical pain and health difficulties. Not surprisingly, their moods were lower on the days when they had more physical pain. But we found that the people who were in more satisfied relationships were buffered somewhat from these ups and downs of mood—their happiness did not decline as much on the days when they had more pain. When they felt worse physically, they did not report declines in mood as much as individuals who were in less satisfying relationships. Their happy marriages protected their moods even on the days when they had more pain.

This might all sound quite intuitive, but there is a very powerful yet simple message nestled in these findings: the frequency and the quality of our contact with other people are two major predictors of happiness.

YOUR SOCIAL OBSERVATORY

Sterling Ainsley, so eager to avoid thinking about any of his relationships, believed he was doing pretty well at social fitness. He thought the way he conducted himself with his kids was healthy, he thought his refusal to divorce his wife whom he rarely saw was somewhat heroic, and he even prided himself on his ability to talk with people—a skill he’d developed in his work life. But when asked to look more deeply in the mirror and consider his relationships, it became clear that deep down he felt quite alone, and he had little understanding of how isolated he was.

So where do we start? How can we come closer to seeing the reality of our own social universe?

It’s good to start simple. First, ask: Who is in my life?

It’s a question that most of us, amazingly, never bother to ask ourselves. Even making a basic list of the ten people who populate the center of your social universe can be illuminating. Try it below; you might be surprised at who comes to mind and who doesn’t.

WHO ARE MY CLOSEST FRIENDS AND RELATIVES?

________________________ ________________________

________________________ ________________________

________________________ ________________________

________________________ ________________________

________________________ ________________________

________________________ ________________________

A few essential relationships—your family, romantic partner, close friends—probably come to mind quickly, but don’t think only of your most “important” or successful connections. List those who affect you from day to day and year to year—good or bad. Your boss or a particular coworker, for example. Even relationships that seem insignificant could make the list. We’ll talk much more about this in a later chapter, but acquaintances and casual relationships built around activities like knitting, playing soccer, or meeting with a book club could be more important to you than you think. The list might also include people you really enjoy but almost never see: for example, an old friend you often find yourself thinking about but with whom you’ve fallen out of touch. It might even include people you only exchange pleasantries with, like the driver of the bus you take to work, whom you look forward to seeing and who gives your day a little jolt of good energy.

Once you’ve got a good set of people, it’s time to ask: What is the character of these relationships?

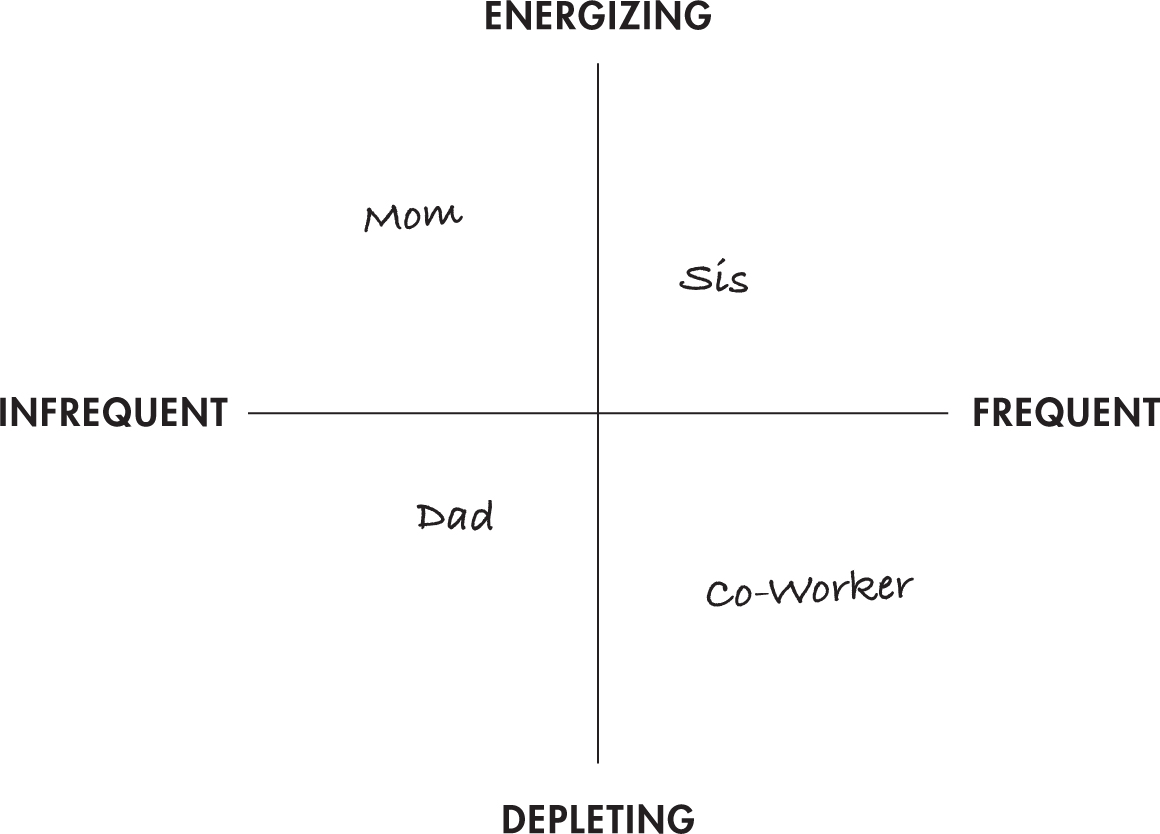

We’ve asked Harvard Study participants a huge variety of questions over the years to try to answer this larger question and create “pictures” (really, datasets) that reflect the character of their social universes. But trying to get some perspective on your own social universe needn’t be as complex as research. You can simply think about the quality and the frequency of contact you have with each person and use two broad dimensions to capture your social world: 1) How a relationship makes you feel, and 2) How often that happens.

Below you will find a chart that you can use to give your social universe a shape on this two-dimensional spectrum. Where you locate someone on this chart should depend on how energized or depleting that relationship feels, and how frequently you interact with that person. It looks like this:

EXAMPLE OF A SOCIAL UNIVERSE

This might seem simplistic at first,… and in a way, it is. You’re taking something intensely personal and complicated, flattening it, and giving it a static place in this social universe; complexities will be shed in the process. That’s okay. This is a first step at capturing the character of the relationships that make your life what it is.

What do we mean by energizing and depleting?

These are subjective terms, and that’s intentional; this is about recognizing how you feel when you are with these individuals. Sometimes we don’t really know how we feel about a relationship until we stop to think about it.

In general, an energizing relationship enlivens and invigorates you, and it gives you a sense of connection and belonging that remains after the two of you part ways. It makes you feel better than you would feel if you were alone.

A depleting relationship induces tension, frustration, or anxiety, and makes you feel worried, or even demoralized. In some ways, it makes you feel lesser or more disconnected than you would feel if you were alone.

This doesn’t mean that an energizing relationship will make you feel good all the time or that a depleting relationship will make you feel bad all the time. Even our most vital relationships have their challenges, and many, of course, are a mixed bag. Your general intuition about each person on your list is the thing you want to capture: When you spend time with this person, how do you feel?

Take a look at the chart and think about where each of the people on your list might land. Do they energize or deplete you? Do you see them a lot, or only a little?

That cherished person you don’t see enough of can act as your starting point. Set them on the map with a small dot—like a star in your social universe.

MY SOCIAL UNIVERSE

As you set your relationships in their place, think about each one. Why is this person in this particular place? What is it about the relationship that compelled you to put them there? Is this relationship where you want it to be? If a relationship is particularly difficult and has been giving you a depleted feeling, do any reasons for this come to mind?

Checking in with each relationship like this can help us appreciate and be thankful for people who enrich our lives, and it can help us see which relationships we want to work on improving. Your answers to these questions will (and should) reflect your own preferences about the amount and kind of social connections that suit you. You might realize that you’d like to see this person more often, but that person is in just the right spot. Maybe this other relationship is depleting but important and needs some special attention. If you have a sense of which direction you’d like a relationship to move, draw an arrow from where they are to the spot you’d like them to be.

We want to make clear that identifying a relationship as depleting does not mean you should cut that person out of your life (although after some reflection you may decide you need to see certain people less often). Instead, it may be a sign that there is something important there that needs your attention. And that means the relationship contains an opportunity.

In truth, almost all relationships contain opportunities; we just have to identify them. Examples include important relationships from our past, positive relationships we have been neglecting, and difficult relationships that may contain the seeds of a better connection. But these opportunities don’t last forever; we have to take advantage of them while we can. If we wait too long, we might find, as Sterling Ainsley did, that it’s too late.

ROSALIE, HARRIET, AND STERLING

Sterling Ainsley was one of the Harvard College men in the Study, but he was not born into privilege. In fact, he was born directly into his older sister’s arms. This was near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1923, and Rosalie, his sister, was 12 years old. She’d been home alone with their mother, who was giving Rosalie a French lesson at the kitchen table when she suddenly went into labor. They did not have a telephone and there was no time to fetch the neighbors or a doctor. Through waves of screaming pain their mother managed to give Rosalie instructions about what to do every step of the way, and Rosalie was able to help deliver Sterling safely. She even tied and cut the umbilical cord. “I was extremely close to Sterling,” Rosalie told the Study. “As far as I was concerned, I was responsible for him. I treated him like my own child.”

Sterling’s father was a steelworker and made just enough to support their family of seven, but he was also a compulsive gambler. Every week he would risk his wages, only a fraction of which made it home, so the older kids were forced to work. Three weeks after Sterling was born, his father committed his mother to a sanitarium. For four months, Rosalie took care of Sterling, feeding him from a bottle. “I remember walking the floor with him, singing songs,” she said. “When my mother came home, she was different. My father was illiterate, but my mother had been a brilliant woman and spoke three languages with us and taught us how to read and write both English and French, but after that she was never the same. She couldn’t take care of Sterling. She didn’t know what to do, even though she’d already raised four kids. So I looked after him for several years.”

When Sterling was nine years old, his father again committed his mother to a sanitarium, this time permanently, and then abruptly moved away, leaving the younger children to fend for themselves. By this time, Rosalie, at 21 years old, was married and had a child of her own, and she and her husband took three of her siblings into their home. She wanted to bring Sterling also, but a family friend, Harriet Ainsley, had recently lost her own son to a tragic accident and offered to take Sterling and raise him as her own. Already strained financially, Rosalie and her husband agreed.

The Ainsleys lived on a farm in rural Pennsylvania and the lifestyle was a shock for Sterling, but his adoptive parents were kind, calm, and supportive. His adoptive father was stern but fair, and taught Sterling everything he could about how to run and operate the farm. When Sterling was 19 he said of Harriet, his adoptive mother, “She means about everything in the world to me. She has been a wonderful mother. I think she has been responsible for my aspiring to anything. She is the one who gave me a great interest in English literature.”

Thanks in part to encouragement from his adoptive mother and his sister Rosalie, Sterling did well in high school, ran (and lost) a campaign for school president, and was accepted to Harvard with a scholarship. When Sterling entered the Study at age 19, Rosalie was asked what she thought of him, and she said, “It’s hard to describe him today. He has a tendency, I think, to bring out the best in people that he comes in contact with. He has high ideals. When I spend a day with Sterling, I feel as though I have been to some higher institution of learning.”

These two brave and resilient women, Rosalie and Harriet, played pivotal roles in Sterling’s life. His biological mother, who was not a part of his life, nonetheless played a vital role through her cultivation of the kindness, caring, and determination in Rosalie that then allowed Rosalie to raise Sterling by herself in those early years. Still, their father was abusive to Sterling, something Rosalie could not control, and the eventual breakup of the family was extremely difficult for Sterling. If it wasn’t for each of the women who loved him in turn, it is highly unlikely Sterling would have gone to college and made a life for himself out west. As working-class women in the early half of the twentieth century, there was much preventing them from pursuing their own personal priorities. But they did their best to help Sterling. He said many times in his interviews how grateful he was for their support and for their love.

And yet he lost touch with both of them.

THE KEYSTONES OF RELATIONSHIPS

We’ve been saying that human beings are social creatures; in essence this simply means that each of us as individuals cannot provide everything we need for ourselves. We can’t confide in ourselves, romance ourselves, mentor ourselves, or help ourselves move a sofa. We need others to interact with and to help us, and we flourish when we provide that same connection and support to others. This process of giving and receiving is the foundation of a meaningful life. How we feel about our social universe is directly related to the kinds of things we are receiving from and giving to other people. When Study participants expressed a sense of frustration or dissatisfaction with their social lives, as Sterling did in his later life, it could often be traced to a particular kind of support that was missing.

Here are the sorts of questions about various types of support that the Study has asked participants about over the years:

Safety and Security

Who would you call if you woke up scared in the middle of the night?

Who would you turn to in a moment of crisis?

Relationships that give us a sense of safety and security are the fundamental building blocks of our relational lives. If you can list specific people in response to the above questions, you are very fortunate—those relationships are crucial to cultivate and appreciate. They help us navigate through times of stress and give us the courage to explore new experiences. What’s essential is the conviction that these relationships will be there for us if things go wrong.

Learning and Growth

Who encourages you to try new things, to take chances, to pursue your life’s goals?

Feeling secure enough to venture out into unknown territory is one thing, but being encouraged or inspired to do so by someone we trust is a precious gift.

Emotional Closeness and Confiding

Who knows everything (or most things) about you?

Who can you call on when you’re feeling low and be honest with them about how you’re feeling?

Who can you ask for advice (and trust what they say)?

Identity Affirmation and Shared Experience

Is there someone in your life who has shared many experiences with you and who helps strengthen your sense of who you are and where you’ve come from?

Friends from childhood, siblings, people you shared major life experiences with—these relationships are often neglected because they have been with us for so long, but they are especially valuable because they cannot be replaced. As the song goes, You can’t make old friends.

Romantic Intimacy (Love and Sex)

Do you feel satisfied with the amount of romantic intimacy in your life?

Are you satisfied in your sexual relationships?

Romance is something most of us hope for, not only for sexual satisfaction, but also for the intimacy of another’s touch, the sharing of day-to-day joys and sorrows, and the meaning that comes with witnessing each other’s experiences. For some of us, romantic love feels like an essential part of life. For others, not so much. Marriage, of course, is not necessarily the benchmark of romantic intimacy. The proportion of people ages 25 to 50 who never marry has increased dramatically in the last half century in many places around the world. In the U.S., this proportion increased, from 9 percent in 1970 to 35 percent in 2018. These figures do not tell us the percentage who experience romantic intimacy, but they are an indicator that in the U.S. more people remain unmarried in their adult lives than perhaps ever before. In addition, some committed partnerships are “open,” including people outside the couple in both sexual and emotional intimacy.

Help—Both Informational and Practical

Who do you turn to if you need some expertise or help solving a practical problem (e.g., you need to plant a tree, fix your WiFi connection, apply for health insurance)?

Fun and Relaxation

Who makes you laugh?

Who do you call to see a movie or go on a road trip?

Who makes you feel relaxed, connected, at ease?

Below you’ll find a table arranged around these keystones of support. The first column is for the relationships you think have the greatest impact on you. Place a plus (+) symbol in the appropriate columns if a relationship seems to add to that type of support in your life, and a minus (-) symbol if a relationship lacks that type of support. Remember: it’s okay if not all (or even most) relationships offer you all of these types of support.

My Relationship With |

Safety and Security |

Learning and Growth |

Emotional Closeness and Confiding |

Identity Affirmation and Shared Experience |

Romantic Intimacy |

Help (Both Info and Practical) |

Fun and Relaxation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Think of this exercise like an X-ray—a tool that helps you see below the surface of your social universe. Not all of these types of support will feel important to you, but consider which of them do feel important, and ask yourself if you’re getting enough support in those areas. If you’re feeling a certain dissatisfaction in your life, do any of the gaps on the chart resonate with that feeling? Maybe you realize you have plenty of people you have fun with, but nobody you can turn to when you need someone to confide in. Or vice versa.

As you fill in and expand this table, you might see some gaps, and also some surprises. You might not have realized that you only have one person you go to for help, or that a person you take for granted actually makes you feel safe and secure, or that another person reinforces your sense of identity in important ways. We know from personal experience (and many conversations over drinks at conferences) that even professionals in the fields of psychology and psychiatry have a hard time seeing their own lives in this way without focused reflection.

MOVING FORWARD

Sometimes this kind of reflection alone will point us in the direction we’d like to go, but even after we see what we’d like to change we may still have trouble taking the first steps.

There is an entire field of research that studies human motivation—why we make the decisions we make, why some people make efforts to change while others never manage it. This research is popular among advertisers, who use it to encourage us to buy stuff. But we can also use it to encourage ourselves to do things we want—like take steps toward growth in our relationships. In fact, we’ve already applied some of it in this chapter: one of the things this research shows is that a key to motivating change is recognizing the difference between where we are and where we would like to be. Defining these two states creates a kind of potential energy that helps us to take that first difficult step. This is what you have started to do with these relational tools. You’ve mapped your social universe and the quality of your relationships, and you’ve reflected on what you might like to change. From here, the process of actually doing it can be messy—particularly for challenging relationships—but the potential rewards are great. We’ll get into that process more in coming chapters, but there are a few things you can do immediately, and some useful principles to keep in mind.

WORKING FROM THE TOP DOWN

Focus first on what’s working well. This is the easiest place to begin. Take a look at the relationships on the energizing side of your social universe and consider how you might solidify or encourage what’s great about them. Tell (and show!) those people how much you appreciate them, and why. It never hurts to double down on what’s already bringing energy and vitality into your life. These relationships are already rolling, but there are usually one or two that have slowed down and need a little push to get up and running at full tilt again. Even good relationships tend to repeat the same routines over and over. It might be time to try some new things with them.

Next, take a look at those relationships that are just peeking over that energizing line, or are maybe a little bit depleting on balance. Is there a way you can give these relationships a nudge, and make them more energizing? Minor changes in these relationships can sometimes relieve small burdens that have been adding up.

The relationships you’ve identified as depleting might require some more consideration and reflection. You might need to take a risk and reach out to someone you might not normally contact, message them, plan a get-together, or invite them to an event. It might mean addressing some emotional elephant in the room like a recent argument or a snarky comment. (That could require some additional preparation, and we’ll talk about navigating disagreements and emotional challenges like this in coming chapters.)

There are some nuts and bolts to this kind of effort. You have to actually make that call, take out your calendar, clear that evening, and make plans. Preferably recurring plans!

But even with your most positive relationships, some of the old habits, the old automatic ways of being and interacting that make the relationship less energizing, may resurface. What follows are a few broad principles that we’ve found both in research and therapy to be effective in enlivening and energizing relationships:

Suggestion #1: The Power of Generosity

In the Western world, with its emphasis on individualism, the myth of the “self-made” man or woman gets a lot of airtime. Many of us imagine that our identity is self-created, that we are who we are because we made ourselves that way. In reality, we are who we are because of where we stand in relation to the world and to other people. The spoke of a wheel, if not attached to a wheel, is just a piece of metal. Even a hermit living in a cave is defined by his relation to, and distance from, other people.

Relationships are necessarily reciprocal systems. Support goes both ways. The support we receive is rarely an exact mirror image of the support we provide, but the old adage “you get what you give” is a good general rule.

This idea of giving what you’d like to receive in return is one answer to the powerlessness and hopelessness that people sometimes feel when they think of their relationships. We can’t directly control the way other people engage with us, but we can control the way we engage with them. We may not be receiving a certain kind of support, but that doesn’t mean we can’t give it.

The Dalai Lama reminds us that what goes around comes around. “We are self-centered and selfish, but we need to be wisely selfish, not foolishly so,” he once said. “If we neglect others, we too lose.… We can educate people to understand that the best way to fulfill their own interest is to be concerned about the welfare of others. But this will take time.”

Research clearly shows that he’s right: helping others benefits the one who helps. There is both a neural and a practical link between generosity and happiness. Being generous is a way to prime your brain for good feelings, and those good feelings in turn make us more likely to help others in the future. Generosity is an upward spiral.

Go back through the questions about support from earlier in the chapter and, thinking honestly about yourself, answer them in the opposite direction: Do you provide these types of support to others? If so, to whom? Are there people in your life you want to support more? Recall Kiecolt-Glaser’s research on caregiver stress and wound healing from earlier in this chapter. If you have people in your life who are caring for others, or who are under major life stress, are there ways you can be there for them, and make sure they are receiving support themselves? If you are a caregiver, are you getting the support you need? As you look over your social universe, how does the balance of giving and receiving feel?

My Relationship With |

Safety and Security |

Learning and Growth |

Emotional Closeness and Confiding |

Identity Affirmation and Shared Experience |

Romantic Intimacy |

Help (Both Info and Practical) |

Fun and Relaxation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suggestion #2: Learning New Dance Steps

We get better at what we practice, and without realizing it we can become very talented at doing things that are not in our interest. Sterling Ainsley, for example, had gotten better and better at avoiding closeness and connection. He had good reason; even though he had his sister, Rosalie, there with him during the first years of his life, she couldn’t stop his father’s abuse, and his family of origin was pulled apart when his father committed his mother to the sanitarium. When Sterling moved to the farm, he could no longer see Rosalie on a regular basis, and this was painful to him. So he carried his fears of close relationships far into his adult life. With the exception of his adoptive mother, he never established that crucial sense of safety and security with another person, let alone with multiple people. Without necessarily articulating it to himself, he lived his life assuming that he would be happier, or at least safer, without close contacts. Being close to others, he believed, was a risk.

He was right, in a way. Our strongest feelings emerge from our connections with other people, and while the social world is filled with pleasures and meaning, it also contains doses of disappointment and pain. We get hurt by the people we love. We feel the sting when they disappoint us or leave us, and the emptiness when they die.

The impulse to avoid these negative experiences in relationships makes sense. But if we want the benefits of being involved with other people, we have to tolerate a certain amount of risk. We also have to be willing to see beyond our own concerns, and our own fears.

This raises that important question of how someone with Sterling’s traumatic history can keep from letting it dominate their life. We hope he would have good experiences of closeness as he got older that would change his reigning paradigm. It happens. A positive, trusting relationship with a spouse can make a less secure person feel more secure. But too many people with Sterling’s history just move from one self-fulfilling prophecy to another and never have a different experience of closeness.

The question is, how do we keep from always fighting the last traumatic battle and open ourselves to new experience?

Suggestion #3: Radical Curiosity

Every man I meet is my master in some point, and in that I learn of him.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

We often struggle in relationships for the same reason we struggle in other areas of life: we become too self-focused. We worry about whether we’re doing it right, whether we’re good at something, whether we’re getting what we want. Like Sterling, or John Marsden, the unhappy lawyer, when we become too self-focused, we can forget about the experiences of others.

It’s a common trap, but it’s not inevitable. The same curiosity that makes us want to experience something new in a book or a movie can inform how we approach our relationships in even the most routine moments of life.

It can be a real joy to lose ourselves in the experience of another person. It can also feel strange at first, if you’re not used to it, and it might take some effort. Curiosity—real, deep curiosity about what others are experiencing—goes a long way in important relationships. It opens up avenues of conversation and knowledge that we never knew were there. It helps others feel understood and appreciated. It’s important even in less significant relationships, where it can set a precedent of caring and increase the strength of new, fragile bonds.

Maybe you know someone in your life who is always talking to people, rooting out their stories and opinions. It’s no coincidence that these people are often very joyful and alive. Just as the “strangers on a train” experiment we mentioned in Chapter Two demonstrated, interacting with other people improves our mood and makes us happier than we expect it will.

Bob thinks of his father, who would talk to strangers everywhere. He was obsessively—radically—curious about everyone. Bob’s aunt and uncle often told a story about how they once got into a cab with him in Washington, D.C. Bob’s father sat in the front, as always, so he could talk to the driver. While he was extracting this man’s entire life story, he started playing with the quarter-glass window that used to be a feature in old cars. He was so absorbed in the conversation that he didn’t realize the window had come off in his hand. Peals of laughter were coming from the backseat, but Bob’s father was too absorbed in his conversation to notice. He set the little window on the seat beside him and started playing with the window crank, which also came off. He set that down, too, and just kept asking questions. Lucky for the car it was a short drive.

This behavior came naturally to him. He didn’t necessarily do it to be kind to people, he did it because it made him feel good. It energized him. Some of us are out of practice and have forgotten how this kind of curiosity can feel, so we have to be more deliberate. We have to take an almost radical approach to cultivating the often subtle seeds of our natural interest in people, and take a bold step beyond our usual conversation habits. We need to make a point to ask ourselves: Who is this person, really, and what’s their deal? Then it’s as simple as asking a question, listening to the reply, and seeing where it takes us.

The crucial point is that being curious helps us connect to others, and this connection makes us more engaged with life. Genuine curiosity invites people to share more of themselves with us, and this in turn helps us understand them. This process enlivens everyone involved. The “strangers on a train” experiment points to these cascading benefits, which we’ll discuss much more in Chapter Ten. Even a small interest in another person, a brief word, can create new excitements, new avenues of connection, and new pathways for life to flow.

Like generosity, curiosity is an upward spiral.

FROM CURIOSITY TO UNDERSTANDING

When people hear that we, Bob and Marc, are therapists, they often react by saying something like, “How can you listen to other people’s problems all the time? That must be exhausting and depressing.” It’s true that listening isn’t always easy, but the more prevalent and powerful experience for both of us is one of gratitude to the people we work with in therapy. We learn from their experience and it deepens our connection to them. One of our greatest joys (and this is not confined to therapy) comes in moments when we sense that we’ve understood the experience of another person and then communicated that understanding in a way that feels true to them. It’s life-affirming to suddenly find oneself in sync with the experience of someone else.

This is a crucial step in connecting with others through curiosity: communicating your new understanding back to them. This is where a lot of the magic happens, where the connection between people becomes solid, visible, and meaningful. Hearing an accurate understanding of our own experience coming from another person, articulated in their words, can be thrilling, especially when we’re feeling alienated in a social setting. Suddenly someone is seeing us as we are, and that experience momentarily breaches the barrier that we feel between us and the world. To be seen is an amazing thing.

Conversely, it’s an amazing thing to really see another person, and to communicate that new sight. The thrill of connection happens both for the person being seen and the person doing the seeing. Again, the connection and the feeling of vitality go both ways.

This is not a new or unconventional idea. The classic and hugely influential Dale Carnegie book How to Win Friends and Influence People, written in 1936, emphasized this point. The book is based on six principles, and the very first is “Become genuinely interested in other people.” As with anything, the more you practice this kind of curiosity, the easier it gets. And the materials for practice are almost always available. You can make a choice right now, today, even in the next few minutes, that will move you in the right direction.

TAKING IT BACK TO LIFE

Just as maintaining social fitness requires some regular exercise, reflecting on all of your relationships benefits from regular check-ins. Don’t hesitate to do it again in the future. If your social fitness is not where you would like it to be, you might want to do these reflective check-ins even more often. It never hurts—especially if you’ve been feeling low—to take a minute to reflect on how your relationships are faring and what you wish could be different about them. If you’re the scheduling type, you could make it a regular thing; perhaps every year on New Year’s Day or the morning of your birthday, take a few moments to draw up your current social universe, and consider what you’re receiving, what you’re giving, and where you would like to be in another year. You could keep your chart or relationships assessment somewhere private, or even right here in this book, so you know where to look the next time you want to peek at it to see how things have changed. A lot can happen in a year.

If nothing else, doing this reminds us of what’s most important; always a good thing. Over and over again, when the participants in the Harvard Study reached their 70s and 80s, they would make a point to say that what they valued most were their relationships with friends and family. Sterling Ainsley himself made that point. He loved his adoptive mother and sister deeply—but he lost touch with them. Some of his fondest memories were of his friends—whom he never contacted. There was nothing he cared more about than his children—whom he rarely saw. From the outside it might look like he didn’t care. That was not the case. Sterling was quite emotional in his recounting of his most cherished relationships, and his reluctance to answer certain Study questions was clearly connected to the pain that keeping his distance had caused him over the years. Sterling never sat down to really think about how he might conduct his relationships, or what he might do to properly care for the people he loved most.

If we accept the wisdom—and more recently the scientific evidence—that our relationships really are among our most valuable tools for sustaining health and happiness, then choosing to invest time and energy in them becomes vitally important. And an investment in our social fitness isn’t only an investment in our lives as they are now. It is an investment that will affect everything about how we live in the future.