6 FACING THE MUSIC Adapting to Challenges in Your Relationships

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

Leonard Cohen

Harvard Study Questionnaire, 1985, Section VI

Q#8: What is your philosophy for getting over the rough spots?

At age 26, Peggy Keane seemed to everyone who knew her to be well on the path to a good life. She had a promising career, and a loving family. We heard from her in Chapter Three as she told us about her marriage to a man she described as “one of the nicest men on the planet.” But this picture of her life did not match the deeper reality. Only a few months after her wedding, Peggy’s life fell into disarray when she acknowledged to herself, her husband, and her family that she was gay. Peggy had been hiding this truth about herself for years, and when she finally turned to face it, her entire world seemed to collapse. She felt alone, out of energy, and out of resources. It was the most difficult moment of her life. When she came up for air after that period of confusion and despair, she looked around at her life and thought, What now? Who can I turn to?

Throughout this book, we’ve been emphasizing that relationships are the key not only to navigating difficulties, big and small, but to flourishing in the face of them. George Vaillant summed this point up well when he wrote: “There are two pillars of happiness revealed by the [Harvard Study].… One is love. The other is finding a way of coping with life that does not push love away.”

It is within our relationships—and especially our close relationships—that we find the ingredients of the good life. But getting there isn’t simple. When we look across the eighty-four years of the Harvard Study, we can see that the happiest and healthiest participants were those with the best relationships. But when we examine the lowest moments in our participants’ lives, a great deal of them also involve relationships. Divorces, the death of loved ones, challenges with drugs and alcohol that pushed key relationships to the brink… many of the hardest times in participants’ lives have been the result of their love for and closeness to other people.

It’s one of the great ironies of life—and the subject of millions of songs, films, and great works of literature—that the people who make us feel the most alive and who know us best are also the people able to hurt us most. This doesn’t mean that the people who hurt us are malicious, or that we are acting maliciously when we hurt others. Sometimes there is no fault. As we travel on our own unique paths, we can hurt each other without intending to.

This is the conundrum we find ourselves in as human beings, and how we deal with challenges often defines the course of our lives. Do we face the music? Or do we bury our heads in the sand?

What did Peggy do?

Let’s fast-forward in Peggy’s life to March of 2016, shortly after her 50th birthday, and take a look at how things worked out for her.

Throughout the 1990s, Peggy focused on her career. She completed a master’s degree and started teaching. After one short relationship and a period of being single, Peggy fell in love in 2001 and has been in a close relationship with the same woman ever since. She describes her relationship as “very happy, warm, and comfortable.” But in 2016 she’d been having some trouble at work, and the stress was affecting her life:

Q1: In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?

Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

Q2: How often have you felt nervous and stressed?

Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

But even though she’d been under pressure, Peggy wasn’t particularly worried:

Q3: How often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?

Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

Q4: How often have you felt difficulties piling up so high that you could not overcome them?

Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

What were the reasons for Peggy’s confidence in tackling problems? In no small part, her friends and family:

Q.43: How much does each statement describe you?

Friends care about you.

Not at all A little bit Some Quite a bit A lot

Family cares about you.

Not at all A little bit Some Quite a bit A lot

Friends help you with serious problems.

Not at all A little bit Some Quite a bit A lot

Family helps you with serious problems.

Not at all A little bit Some Quite a bit A lot

Peggy went through the wringer and came out on the other side, and her relationships are what helped her through. Because of her full engagement with the people who are close to her, she’s lived, as Zen Buddhists sometimes say, “the ten thousand joys and the ten thousand sorrows.”

As we travel along our individual paths, one of the few things we can be absolutely sure of is that we will face challenges in life and in our relationships that we don’t feel equipped to handle. The lives of two generations of Harvard Study participants broadcast this truth loudly and clearly. It doesn’t matter how wise, how experienced, or how capable we are; we will sometimes feel overmatched. And yet if we are willing to face into these challenges, there is a tremendous amount that can be done. “You can’t stop the waves,” Jon Kabat-Zinn wrote, “but you can learn to surf.”

In Chapter Five, we talked about the importance of paying attention to the present moment, and the incredible value of directing that attentiveness toward the people in our lives. Now the question becomes: What happens when we find ourselves in that present moment, engaged with people and experiencing significant challenges? Life happens only in the moment. If we’re going to face the music, we have to do it one moment at a time, one interaction at a time, one feeling at a time.

This chapter is about these moment-to-moment choices and interactions, about living with and adapting to challenges in our relationships and in life, so that when the waves come crashing our way, rather than succumbing to them, we can meet them with all of the resources at our disposal, and ride.

REFLEXIVE VS. REFLECTIVE

Many difficulties in relationships stem from old habits. We develop automatic, reflexive behaviors over the course of our lives that become so intimately woven into our days that we don’t even see them. In some cases, we become used to avoiding certain feelings and turning away, while in other cases we might be so overcome by emotion that we act on our feelings before we realize it.

The old phrase “knee-jerk reaction” is apt. When a doctor taps our knee in just the right spot, our nerves react and our foot kicks up. No thought or conscious effort is involved. Emotions often seem to affect us in the same way. A great deal of research has shown that once an emotion is elicited, our reactions are almost automatic. Emotional reactions are complex but include what researchers have called an “action tendency”—an urge to behave in a certain way. Fear, for example, includes an urge to escape. Emotions have evolved to enable rapid responses, particularly when we feel threatened. So when humans lived primarily in the wilderness, action tendencies had a strong survival benefit. Now things are less straightforward.

When Bob was a medical student, he encountered two cases that put into relief a crucial difference between more adaptive and less adaptive ways of coping with stress. Both involved women in their late 40s, each of whom had found a lump in her breast. We’ll call them Abigail and Lucia. Abigail’s initial reaction to the lump was to minimize its significance, and to tell no one. It was probably nothing, she decided. It was small, and whatever it was, it wasn’t important. She didn’t want to bother her husband or her two sons, who were away at college and busy with their own lives. After all, she felt fine and had other things to worry about.

Lucia’s initial reaction was alarm. She told her husband, and after a brief conversation they agreed she should call her doctor and schedule an immediate appointment. Then she called her daughter and let her know what was going on. While she waited for the biopsy results to come back, she did her best to put it out of her mind so that she could get on with her life. She had a career, and other things to deal with. But her daughter called every day and her husband doted on her to the point that she had to ask him for some space.

Abigail and Lucia were both responding to an incredible stressor in ways that were natural for them. We all do this. Our habitual responses—patterns of both thinking and behaving—that arise when stressful events occur are what psychologists call coping styles.

Our coping styles affect the way we deal with every challenge that comes our way, from a minor disagreement to major catastrophe, and a key part of every coping style is how we use our relationships. Do we seek help? Do we accept help? Do we turn inward and face challenges in silence? Whatever coping style we use has an impact on those around us.

The coping styles of the two women that Bob encountered in his medical training could not have been more different. Abigail managed her fear by denying the significance of what she had discovered, and in this way she faced away from the difficulty. She did not involve her loved ones and did not take any action. She saw her situation as a potential burden on others. Lucia was also afraid, but she used her fear to face toward the difficulty and to take the actions necessary to preserve her health. She saw her situation as a matter that was larger than herself, something her family should face together. She leaned in to the situation, dealt with it directly, but remained flexible as well, managing the ebb and flow of the other demands of her life.

It turned out that both of these women had cancer. Abigail never told her family or her doctor what she had found and ignored the lump until she began to feel ill. By then it was too late, and the cancer took her life. Lucia caught the cancer early, went through a long course of treatment, and survived.

This is an extreme example, but this contrast in outcomes stuck with Bob for the clarity of its message: the inability or refusal to face challenges directly and to engage your support network can have enormous consequences.

FACING THE MUSIC VS. BURYING OUR HEADS IN THE SAND

Abigail’s case is not unusual at all. Marc has helped run two separate studies designed to help women with breast cancer deal more directly with their fears and to access the support of important people in their lives. Among these women, Abigail’s initial reaction—avoidance—was common.

It’s often easier to turn away than it is to confront what troubles us. But doing so can have unintended consequences, and the effect of avoidance can be especially pronounced in the place it happens most: our personal relationships.

Many studies have shown that when we avoid confronting challenges in a relationship, not only does the problem not go away, but it can get worse. The original problem keeps burrowing down into the relationship and can lead to a variety of other problems.

This has been clear to psychologists for a long time, but what has been less clear is how this kind of avoidance can affect us over the course of life. Does a tendency to avoid dealing with challenges affect us only in the short term, or are there long-term consequences?

To get a lifetime perspective on this question, we used data from the Harvard Study and asked, What happens over the course of an entire life when a participant tends to face the music (lean in), and what happens when they tend to bury their heads in the sand (avoid)? We found that a tendency to avoid thinking and talking about difficulties in middle age was associated with negative consequences more than thirty years later. Those people whose typical responses were to avoid or ignore difficulties had poorer memory and were less satisfied with their lives in late life than those who tended to face difficulties directly.

Of course, life is always bringing us new and different challenges. What served you well yesterday might not work today, and different kinds of relationships require different skills. The friendly joking to lighten an argument with your teenage child probably will not work with your neighbor who asks you to curb your dog. During a heated exchange at home, you might take your partner’s hand; at work your boss might not appreciate the same gesture. We need to cultivate a variety of tools and use the right tool for the right challenge.

One lesson from research is that there are advantages to being flexible. There are men and women in the Harvard Study who are incredibly strong-willed. They have set ways of responding to challenges, and they stick to them. In some situations, they may find themselves in control, but in others they may be at a loss.

It was not uncommon in the 1960s, for example, for our First Generation Study participants to have difficulty finding common ground with their baby boomer children. This inability to adapt caused them stress.

“I don’t like that hippy movement,” Sterling Ainsley told the Study in 1967. “It disturbs me.” He found himself alienated from his children, unable to be curious about their different views of the world.

Each of us has cultivated certain coping strategies through our lives, and they can become set in stone. This kind of “strength” can actually make us more fragile. In an earthquake, the sturdiest, most rigid structures are not the ones that survive. In fact, they might be the first to crumble. Structural science has figured this out, and building codes now require flexibility in tall structures, so that buildings are able to ride the literal wave rolling through the earth. The same with human beings. Being able to flex with changing circumstance is an incredibly powerful skill to learn. It might be the difference between getting through with minor damage and falling apart.

Changing our own automatic way of responding is not an easy thing to do. There are brilliant people in the Harvard Study—actual rocket scientists—who never managed even to recognize, much less control, their own coping strategies, and their lives were poorer for it. At the same time, participants like Peggy Keane, and her parents, Henry and Rosa, were able to grow by facing the trials of their lives as squarely as they could, and by using the support of friends and family.

So how do we move beyond our initial reactions when confronted by challenges?

When we are in the throes of emotional events, positive or negative, minor or major, our reactions often unfold so fast that we experience our emotions as if they are happening to us, and we are at their mercy. But in truth, our emotions are much more affected by our thinking than we realize.

There is now a great deal of research showing the connection between how we perceive events and how we feel about them. Humans understood this long before science developed the objective evidence.

“A happy heart is good medicine and a cheerful mind works healing,” the Bible says, “but a broken spirit dries up the bones” (Proverbs 17:22).

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus noted that “Men are disturbed not by events, but by the views they take of them.”

“Monks,” the Buddha said, “we who look at the whole and not just the part, know that we too are systems of interdependence, of feelings, perceptions, thoughts, and consciousness all interconnected.”

Our emotions need not be our masters; what we think, and how we approach each event in our lives, matters.

ONE MOMENT AT A TIME

If we take any emotional sequence—a stressor that evokes a feeling that elicits a reaction and its aftermath—and we zoom in and slow the sequence way down, a new hidden level of processing is revealed. Just as medical researchers find treatments for illness by looking at the smallest processes in the body, some surprising possibilities become available to us when we examine our emotional experience at a more microscopic level.

This process—from stressor to reaction—happens in stages. Each stage presents us with a range of choices that can propel us in a more positive or more negative direction, and each stage can be altered by our thinking or behavior.

Scientists have mapped these stages and used these maps to help children curb aggression, to help adults reduce depression, and to help athletes perform at peak efficiency. But these maps are useful for anyone in any emotional situation. By understanding how we move through these stages, and slowing them down, we can illuminate some of the mysteries behind why we feel the way we feel and do the things we do.

The model that follows provides a way for you to slow your reactions and put them under a microscope. We offer it as something you can keep in your back pocket (metaphorically) and use anytime, for any emotional situation. Our main focus in this book is on relationships, so we present examples of how this model can be used to respond to challenging experiences with other people. But it can be applied to challenges of all sorts—to unexpected and minor irritants like getting a flat tire, or to chronic health stressors like diabetes or arthritis. One moment at a time.

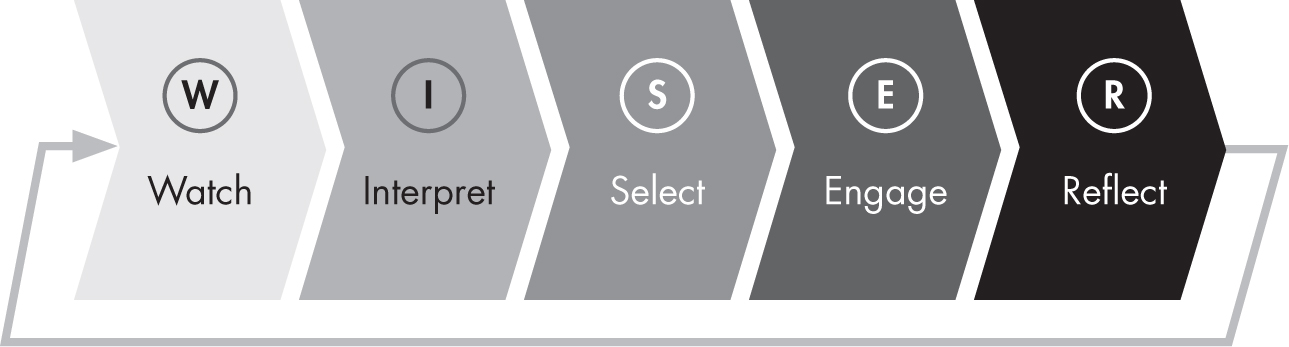

THE W.I.S.E.R. MODEL OF REACTING TO EMOTIONALLY CHALLENGING SITUATIONS AND RELATIONSHIP EVENTS

This model downshifts our typical reactions one or two gears and gives us a chance to look more closely at the rich particulars of situations, the experiences of other people, and our own reactions that we may have been missing.

To show you how this model can be used in everyday life, we’ll use a scenario we see a lot, both in our clinical practices and among participants in the Harvard Study: a family member who offers unwelcome advice.

Imagine a mother, we’ll call her Clara, who has been having difficulty connecting with her teenage daughter, Angela. Angela is fifteen, and as most fifteen-year-olds do, she’s striving to become more independent. She feels stifled by her mother and father and wants to spend time only with her friends. Angela has been a good student most of her life, but in the last year her grades have been slipping, she’s been caught drinking several times, and she’s been skipping classes, all of which have caused fights at home.

Angela’s grandparents are sympathetic—Clara was defiant at that age herself—and they try to be supportive and leave the parenting to Clara. But Clara’s older sister, Frances, also has teenage kids and thinks that Angela’s parents are failing her. Aunt Frances worries about where Angela’s headed and feels like it might be her duty to intervene.

At a family barbecue, Frances sees her niece Angela at the end of the picnic table, disengaged, texting with friends. “You know, smartphones kill the brain,” she says, jokingly. “They’ve basically proved it in the lab.” Then she says to her sister Clara, her tone still trying to communicate humor but with a hint of seriousness, “You wonder why her grades are slipping, maybe you should try disciplining her, take the phone away. That’s what I do with my kids. Maybe then she’ll have time for schoolwork.”

Okay—so how could Clara use the W.I.S.E.R. model to help her decide how to respond to her sister?

Stage One: Watch (Curiosity Cures the Cat)

There’s an old adage in psychiatry: Don’t just do something, sit there.

Our initial impressions of a situation are powerful, but they are rarely complete. We tend to focus on the familiar, and this narrow view risks excluding potentially important information. Regardless of how much you can observe initially, there is almost always more to see. Whenever you encounter a stressor and you feel the emotion brewing, a bit of purposeful curiosity right away is useful. Thoughtful observation can round out our initial impressions, expand our view of a situation, and press the pause button to prevent a potentially harmful reflexive response.

In Clara’s case, taking a moment to watch won’t be easy. She has a long history of fraught interactions with her sister, and her first reaction is to feel insulted. Frances’s comment hurts, because Clara feels some shame about her inability to reach Angela, her inability to connect. Her knee-jerk response might be to snap and sarcastically reply with something like, “Thanks for the awesome advice, now how about you mind your own business!” From there, an argument might ensue. Another response might be to say nothing, keep her feelings inside, run over the comment again and again in her mind, and harbor her resentment and shame until she’s furious by the time of the next family get-together.

Watch refers to the entire situation: the environment, the person you’re interacting with, and you. Is the situation unusual or common? What typically happens next? What have I not considered that might be an important part of what is unfolding?

For Clara, this might mean thinking about how her sister experiences these family functions. Maybe Frances is not comfortable around Clara because Clara has always been “the cool aunt.” Or there could be some stress in Frances’s life, such as concern about their mother’s health, that has nothing to do with what’s happening in the moment. This watch phase might take some time and even extend over the next hour or so. Clara might let Frances’s comment go in the moment and then ask her mother what she thought was going on there. If she did this, she might learn that Frances has been having fights with her husband, or that she’s feeling pressured at work. This kind of consideration is not meant to excuse behavior, but simply to flesh out the context of what’s happening. Context is incredibly valuable. It never hurts to take in as much information as possible, beyond what you notice right away.

The curiosity that we muster during the watch phase also includes curiosity about your own emerging reactions—how you’re feeling, and why. You might notice what’s happening in your body, that your heart is beating faster, that you’re pursing your lips or gritting your teeth (signs of anger). You might notice an impulse to lash out or to hide yourself because you feel ashamed. Becoming more conscious of how you react and what you might be about to do can help you ride that wave of emotion rather than having it crash over you.

This leads us to the second stage, which is a critical turning point in response to stress: interpreting what the situation means for you.

Stage Two: Interpret (Naming the Stakes)

It is in this stage where things often go wrong.

Interpreting is something we are all doing, all the time, whether we know it or not; we look around at the world, at what is happening to us, and we assess why those things are happening, and what it means for us. Of course, we build this assessment on reality, but reality is not always so clear-cut. Each of us perceives and interprets a situation in our own way, so what we see as “reality” may not be what other people see. One of the major pitfalls is thinking that a situation is all about us; it rarely is.

If you want to understand a situation as clearly as possible, you first need to make sense of what’s at stake for you. Emotion is usually a sign that there is something important going on for you; if there wasn’t, you wouldn’t be feeling anything. An emotion could be related to an important goal in your life, a particular insecurity, or a relationship you cherish. Asking the question, Why am I getting emotional? is a good way to figure out what’s at stake for you. If you see the stakes clearly, you may be able to interpret the situation more skillfully.

Bob refers to this stage as “filling in the blank.” Because our observation of a situation is rarely complete, we often jump to conclusions about what we don’t know. Many situations are ambiguous and unclear, and it is on this canvas of ambiguity that we can project all sorts of ideas. If we’ve only done a quick-and-dirty job of observing in the watch stage, we probably don’t have all the information we could have about what’s really going on, which leads to hasty conclusions.

In Clara’s case, she might think, Why did that comment make me so mad? Is this about my sister, or about my difficulties with Angela, or just about Angela? My feelings are incredibly strong—why is this so important to me?

Considering her sister, she might think, Is Frances doing this on purpose to hurt me or is she doing this because she really thinks she’s going to help Angela? Is it because she resents that I don’t encourage her to be more involved in Angela’s life? Is it possible that she doesn’t feel valued in the family as the elder sister who has useful advice?

When we fill in the blanks, we sometimes make mountains out of molehills. It often happens that we snag on negative aspects of a stressor and turn something small and manageable into something enormous and overwhelming.

Just asking the question—What is it I’m assuming here?—can bring what looks like a mountain closer into line with its molehill reality. Assumptions are the source of an incredible amount of misunderstanding. As the old saying goes, Never assume, because when you assume, you make an ass of u and me.

But it’s also possible to err in the opposite direction and make true mountains into molehills, as in the example of Abigail, who found a lump in her breast and told no one. If we’re trying to minimize or avoid thinking about a big problem, we might ignore it entirely.

The important thing in the interpret stage is to expand our understanding beyond our initial automatic perception. To consider more perspectives, even if those perspectives are uncomfortable. To ask, What might I be overlooking here?

Again, this is a place where some attention to our own emotions can be helpful. When you feel a pulse of fear, a pulse of anger, or a sinking feeling in your stomach, think of it as a signal to inject some healthy curiosity into the situation, to ponder not only the stressor itself, but also your own emotional reality: Why am I feeling this way? Where are these emotions coming from? What is really at stake? What is so challenging for me about this situation?

Stage Three: Select (Choosing from the Options)

You’ve made a point to watch, you’ve interpreted (and then reinterpreted) the situation and expanded your view; now the question becomes, What should I do?

When we are under stress, we sometimes find ourselves reacting before we have considered our options, or even considered that we might have any options. Slowing down can allow us to consider possibilities and think about the likelihood of success for those possibilities: Given what’s at stake and the resources at my disposal, what can I do in this situation? What would be a good outcome here? And what is the likelihood that things will go well if I respond this way instead of that way?

It’s in the select stage that we clarify what our goals are and what resources we have at our disposal. What do I want to accomplish? How best can I accomplish that goal? Do I have strengths that can help me (e.g., humor and an ability to take the edge off heated conversations), or weaknesses that could hurt me (e.g., a tendency to snap when criticized)?

Let’s say that Clara has talked to her mother and gotten some perspective. She realizes that Frances really is worried about Angela, but Frances doesn’t understand that the situation is different than with Frances’s own kids. Clara realizes she has more than one goal here: she wants to maintain a positive relationship with her sister, protect her daughter from criticism, and also feel good about her ability as a mother.

So now Clara thinks about what she should do; the options, and the likelihood that each option will lead to a positive outcome. She worries that if she does nothing, Frances will continue criticizing her child and blaming Clara for not being a good enough parent. So she decides to say something. But how? And when? They often rib each other, but Clara doesn’t feel like joking when her feelings are hurt, and she knows any joke will sound passive-aggressive and make things worse. So she decides to wait until she and Frances are alone, and talk to her then. In thinking about this talk, she realizes that Frances might actually be a helpful sounding board for some of her struggles with Angela, but she definitely does not want Frances to give advice.

Clara has to choose among options at this stage. One response may not (and probably will not) be the end of it. No one approach by itself is likely to be effective in addressing all the challenges in a complicated situation or in a relationship across time. Clara may try multiple strategies with her sister in the coming months. And, of course, circumstances change; her sister may have some highly visible and difficult parenting challenges of her own, and this might change how Clara responds to her sister.

Selecting a strategy is highly personal. Cultural norms and our individual values play important roles here. Confronting someone directly is considered bad manners in some cultures, while in others it is considered mature and authentic. Often, it comes down to intuition honed by experience—what feels like the best way to respond to this situation, in this moment.

Using the W.I.S.E.R. model as a guide for responding to a stressor may at times be difficult. The stressor may happen fast and there may not be time to slow down your response. Or the source of stress may recur and evolve over time, so you may need to revisit these stages as the situation changes. The key is to try to slow things down where you can, zoom in, and move from a fully automatic response to a more considered and purposeful response that aligns with who you are and what you are seeking to accomplish.

Stage Four: Engage (Implementing With Care)

Now it’s time to respond as skillfully as possible, to engage the strategy you’ve selected. If you’ve taken some time to observe and interpret the situation, and if you’ve made some effort to consider the possibilities and their likelihood of success, your response is more likely to succeed. But the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Even the most logical response can fail if we do a poor job implementing that strategy. Practice—either in our minds or running it by a trusted confidant—can help. Chances of success also increase if we first reflect on what we do well and what we don’t do so well. Some of us are funny, and we know that people respond well to our sense of humor. Some of us are more soft-spoken, and we know that quiet discussion in private settings is more comfortable for us.

Clara gets up the nerve to say something when she and Frances have cleared the dishes together and they are alone in the kitchen. She’s direct, and calm; her emotions are still there but they are more in the background. At first it goes well; Frances is apologetic for offering unsolicited advice (she’s been thinking about her comment, too, and felt bad for how it came out). The two of them agree that they both want what’s best for Angela, and Clara shares some recent problems, which Frances understands. Then Clara says something about Angela being her own person and not being like Frances’s kids (it sounded so good in her head!) and the situation turns quickly. Frances really has been under a lot of stress at work and arguing more than usual with her husband, so Clara’s comment hits a raw nerve. They start to argue again, and then are interrupted by their mother.

“I kind of like it when you fight,” their mother says.

“Like it? Why?”

“Because it reminds me of what you were like when you were younger, and I feel like I’m 35 again.”

They laugh. But soon that feeling wears off, and the two sisters leave the barbecue with strong emotions and things still not fully resolved.

Stage Five: Reflect (Monday Morning Quarterbacking)

How did that work out? Did I make things better or worse? Have I learned something new about the challenge I’m facing and about the best response?

Reflecting on our response to a challenge can yield dividends for the future. It’s in learning from experience that we truly grow wiser. We can do this not only for something that just happened, but for events both big and small that have happened in the past and linger in our memories. Take a look at the worksheet below and consider using it to reflect on an incident or situation that’s troubling you.

WATCH |

Did I face the problem directly or try to avoid it? |

Did I take time to get an accurate assessment of the situation? |

Did I talk with the people involved? |

Did I consult with others to get their understanding of what happened? |

INTERPRET |

Did I recognize how I felt and what was at stake for me in this situation? |

Was I willing to acknowledge my role in the situation? |

Have I focused too much on what is going on in my own head and not enough on what is going on around me? |

Are there alternative ways of understanding what is going on in this situation? |

SELECT |

Was I clear about the outcome I wanted? |

Did I consider all the available options for responding? |

Did I do a good job identifying resources available to help me? |

Did I weigh the pros and cons of different strategies to achieve my goals? |

Did I choose the tools that would work best in meeting the current challenge? |

Did I reflect on IF or WHEN I should do something about the situation? |

Did I consider who else could be involved in solving the problem or meeting the challenge? |

ENGAGE |

Did I practice my response or run it by a trusted confidant to increase the likelihood that it would succeed? |

Did I take steps that are realistic for me? |

Did I evaluate progress and was I willing to adjust as needed? |

What steps did I rush through or mess up or skip over? What did I do well? |

REFLECT |

In light of all I’ve just reflected on, how would I do things differently next time? |

What have I learned? |

Don’t worry if this list of questions, or even the W.I.S.E.R. model in general, seems like too much to think about at once. Many of the steps in the W.I.S.E.R. model may be things you already do instinctively, and 90 percent of everyday life doesn’t require this kind of reflection. Think of the model and this list of questions as a kind of coaching tool for that final 10 percent of life when you feel stuck, or you notice yourself behaving in ways that don’t serve you well.

When it’s all over, the consideration of what happened, and why, helps us to see things we may have missed, and helps us understand the causes and effects of these emotional cascades that may have escaped our notice. If we’re going to learn from our experience and do better next time, we have to do more than just live through it. We have to reflect. In doing so, when we find ourselves in the heat of a similar moment next time, we may be able to take that extra split second to consider the situation, clarify our goals, consider options for responding to it, and move the needle of our lives in the right direction.

GETTING UNSTUCK

The W.I.S.E.R. model is most straightforward when it is applied to discrete relationship challenges. But stress comes in all varieties, and many involve more chronic patterns in our relationships. Sometimes we encounter similar things over and over in a relationship, the same arguments, the same annoyances, the same sequence of unhelpful responses. We end up feeling that we are not moving forward, and we can’t imagine getting out of our current rut. The two of us, Bob and Marc, refer to this feeling with the highly scientific name of stuckness.

We see this both in our Harvard Study participants and among people who come to us seeking psychotherapy. People often feel stuck in their lives and may not be able to articulate fully why they feel that way. They may find themselves having the same disagreements with a partner over and over, no longer able to have even a simple conversation that does not get heated. At work, it might feel like a boss is frequently micromanaging and finding fault, leading to a sense of worthlessness that can be difficult to overcome. (In fact, work relationships that fall into a rut are some of the most vexing. More on that in Chapter Nine.)

For example, John Marsden from Chapter Two found himself deeply lonely in his early 80s, in part because he and his wife were locked in a repetitive cycle of not giving each other what they most needed—affection and support.

Q: Do you ever go to your wife when you’re upset?

A: No. Definitely not. I would get no sympathy. I would be told that it’s a sign of weakness. I mean I can’t tell you the negative signals I get all day it’s just… it’s so destructive.

John was thinking about the reality of his life—about real conversations with his partner. But without realizing it, he was also constructing that reality. His isolation from his wife became a self-fulfilling prophecy. He saw every new encounter with her as proof of his theory: She doesn’t want to be close to me, I can’t trust her with my feelings.

As the modern Buddhist teacher Shohaku Okumura writes, “The world we live in is the world we create.”

As in many Buddhist teachings, there is a double meaning there. Humans physically create the world we live in, but at every moment we are also creating a picture of the world in our minds by telling stories to ourselves—individually and collectively—that may or may not be true.

No two relationships are the same, but one person will often get stuck in similar places in different relationships. The old saying, “We’re always fighting the last battle,” is very true. We tend to think that the thing that happened to us before is about to happen again, whether that is the case or not.

At their core, feelings of stuckness come from patterns in our lives. Some patterns help us navigate life efficiently and quickly, but others may lead us to respond in ways that don’t serve us well. These patterns may include spending time with the wrong people—the wrong friends, and even the wrong partners. Far from being random, these patterns often reflect areas of preoccupation and struggles from our past, which in a way feel like home. They are like a set of familiar dance steps that we fall into. A familiar sensation, even if it’s negative, is activated in a conversation with someone, and there is a kind of comfort in that familiarity. Oh here it is again, I know this dance.

Most of us feel a certain amount of stuckness to some degree, so the question is really about the strength of that feeling. Is it consistently diminishing your quality of life? Is it pervasive, shaping many or most areas of your daily experience?

Bob was stuck in a pattern himself earlier in his life. He dated a series of women, and his friends were consistently surprised at the partners he was choosing. The relationships kept souring. Feeling stuck, he went into psychotherapy, and in describing each of these failed relationships to his therapist, he saw that these failures weren’t coincidences or a string of bad luck. His therapist helped him realize that he’d been choosing the same type of person over and over again—a type of person with whom he was not compatible. Getting honest perspectives on your life from people you trust can be very illuminating in your effort to become unstuck. Such trusted observers will almost certainly see things that you can’t.

You may also be able to do something like this yourself by asking, If someone else was telling me this story, what would I think? What would I tell them? This kind of self-distanced reflection can shed new light on old stories.

Realizing that you may not be seeing the whole picture is a big first step in breaking free of mental patterns that lock us in. The Zen master Shunryu Suzuki taught that it is a positive thing to approach some situations in life as if you’ve never lived them before. “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities,” he wrote, “but in the expert’s mind there are few.” We all feel like experts when it comes to our own lives, and the challenge is to stay open to the possibility that there is more we can learn about ourselves—to allow ourselves to be beginners.

RELATIONSHIPS, ADAPTATION, AND THE END OF THE WORLD

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck the world in 2020, the social isolation, financial strain, and constant worry was an enormous shock to societies all over the globe. As the pandemic and lockdowns continued, isolation and anxiety around the world surged. Stress levels went through the roof. It was, by many measures, a challenge on a scale that the world had not experienced since World War II.

When the pandemic began, we went back to our Study records to read once more what our original Study members told us about how they got through big life crises. They had grown up in the Great Depression, and most of the college men had served in World War II. What most of them recalled was that in order to survive these great crises, they leaned on their most important relationships. The men who fought in the war talked about the bonds they formed with their fellow soldiers and how important those bonds were, not just for their safety but also for their sanity. After the war, many talked about how important it was to be able to share at least part of their experiences with their wives. In fact, those who did so were more likely to stay married. The support they got from others during those hard times, and later in processing them, was crucial. And we find that today.

The pandemic froze our lives, locked us in with those we live with, kept us apart from the friends and coworkers we were accustomed to seeing every day. We never signed up to be with our spouses and children 24/7, but we had to make do. Many older adults never dreamed that they’d be separated from their precious grandchildren for more than an entire year.

Flexibility became more important than ever. To survive we had to give each other space, cut each other slack. If we needed distance from a spouse, it may not have been because there was something wrong with the relationship but because these were abnormal times.

Sadly, Covid-19 won’t be the last global catastrophe, or the last pandemic. These things will continue to come… and go. That’s the nature of life.

The Harvard Study teaches us that it’s crucial to lean on those relationships that can hold us up when things go sideways, just as the Study families did during the Great Depression, World War II, and the Great Recession in 2008. Through the Covid-19 pandemic, that meant staying in touch, in a purposeful way, with people who were now suddenly distant from us. Sending that text, setting up a video chat, making a phone call. Not just thinking of a distant friend but reaching out. It meant being patient with the people we love and asking for help when we needed it. The same will be true for the next crisis, and the next.

For Marc, the idea that relationships help us navigate major challenges is quite personal.

In December of 1939, at the same time that Arlie Bock was interviewing Harvard College sophomores in his mission to figure out what makes people healthy, Marc’s father, Robert Schulz, then 10 years old, was on a passenger ship with his older sister, crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Born to a Jewish family in Hamburg, they’d fled Nazi Germany, and arrived in the United States with only the clothes on their backs, two small suitcases, and no clear plan.

But they were alive. And for one major reason: Marc’s grandmother’s natural habit of forming deep connections with people.

Marc’s father remembers an idyllic early life as a child in Hamburg. Even as his family navigated his father’s death at a young age, he was surrounded by family and friends. Life was good. His family’s textile business was thriving, and he was into gymnastics and playing the piano. Marc heard him talk often about the beauty of Hamburg, the lake at the center of the city, and especially marzipan, a sweet, almond-flavored German treat, a staple of his early childhood.

He had a charmed life back then, he always said.

But things began to change as the Nazis consolidated power and began their campaigns against Jews. Etched in his memory was a particularly scary day and night in November of 1938 when he was nine years old. During the evening of terror that would come to be known as Kristallnacht, or “Crystal Night,” many Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues in his neighborhood were destroyed or burned to the ground. The next day, the Gestapo came to his school and rounded up many of the Jewish teachers and students.

As deportations and detentions of Jews were being conducted all over the city, Marc’s grandmother reached out to close friends of hers, a German family that ran a dairy down the street. They agreed to hide Marc’s father and his family in the basement of the dairy. Without the combination of this kindness and a great deal of luck, they would not have survived.

Even to this day, Marc stays in touch with the descendants of that family in Germany, who tell the same story but from the perspective of their parents and grandparents, who’d made a decision in the moment to protect their friends at grave risk to themselves. It was an act of kindness that could have cost them their lives. Without them, Marc would not exist.

ACCEPTING THE BIG RISK

The question for us in our daily lives is: When we confront personal or global challenges, when people hurt us, or when we find that we have hurt others… what do we do?

Human beings are mysterious, wonderful, dangerous creatures. We are at once vulnerable and incredibly resilient. We have the capacity for creating both magnificent beauty and vast destruction.

That’s the big picture. But if we zoom in a little bit and focus on the life of a single person… your life, let’s say… and even the small events and stresses in your life, the complexity of who we are remains.

If you’re like most people, you struggle, at least sometimes, to understand the people in your life—from those you love most to those you barely know. It’s difficult to really connect with other people and know them. It’s difficult to love and to be loved. It’s difficult to keep from pushing love away.

But making the effort can bring joy, novelty, safety—and sometimes it can even be lifesaving. Slowing down, attempting to see difficult situations clearly, and cultivating positive relationships can help us manage the waves, whether they come from a political crisis, a strange virus that travels around the globe, a moment of reckoning about who we really are, or a rush of anger at a family barbecue. Our initial, automatic responses are not the only ways we can respond. Recognizing this can allow us to pause in the midst of challenge, in the midst of our own bad luck, our own repeating problems, even our own mistakes, and chart a path forward.

In the coming chapters, we will talk about applying the ideas we’ve discussed so far to particular kinds of relationships. Every type of relationship is a little bit different; family relationships are different from work relationships, which are different from marriages, which are different from friendships. Of course, sometimes these categories overlap. Our family members might also be our coworkers, and our siblings might also be our best friends. Still, broad categories can be helpful to consider, while still remembering that each relationship is unique and requires its own kind of attention and adaptation. In the next chapter, we’ll start close to the heart, with the person beside you.