7 THE PERSON BESIDE YOU How Intimate Relationships Shape Our Lives

When we were children, we used to think that when we were grown-up we would no longer be vulnerable. But to grow up is to accept vulnerability.… To be alive is to be vulnerable.

Madeleine L’Engle

Harvard Study Questionnaire, 1979

In Plato’s Symposium, Aristophanes gives a speech about the origin of human beings. In the beginning, he says, every human had four legs, four arms, and two heads. They were strong and ambitious creatures. Zeus, in order to diminish their fearsome powers, split them all down the middle. Now, walking on only two legs, every human is in search of their other half. “ ‘Love,’ ” Plato says, “is the name for our pursuit of wholeness, for our desire to be complete.”

After thousands of years, this idea still resonates.

“Jean is my better half,” Dill Carson, one of the inner-city Boston participants, told the Harvard Study when asked about his wife. “Every evening we sit down and have a glass of wine. It’s a kind of ritual, I don’t feel the day is complete without it. We talk about the things we’re feeling and what’s going on. If we had an argument, we’ll talk about that. We talk about plans, about the kids. It kind of rounds out the day, smooths over the rough edges. If I had to do it all over again, I’d marry the same woman, without a doubt.”

My better half… It’s a sentiment that a number of Harvard Study participants expressed when asked about their partners. The deepest and most positive intimate connections often gave participants a feeling, as Plato was suggesting, of balance and unity.

Unfortunately, there is no universal formula for happy partnerships, happy romances, happy marriages, no single magical key that can unlock the joys of intimate companionship for everyone. The way two “halves” might fit together varies from culture to culture, and of course from one particular relationship to the next. Even from one era to another, or one generation to another, the forms of relationships change. Most of the original participants in the Harvard Study, for example, were married at some point in their life, partly because this was the most acceptable expression of commitment at the time. Today, the variety of committed relationships is increasing, and formal marriage is becoming less common. In the United States in 2020, 51 percent of all households did not consist of any married couples. In 1950, the number was closer to 20 percent. But a change in form doesn’t necessarily mean a change in feeling; human beings remain much the same. Even within the range of seemingly “traditional” marriages there can be a lot of variation. Love comes in all shapes and sizes.

Take James Brewer, one of the Study’s college participants. He came from a small town in Indiana, and when he first arrived at Harvard he was an intelligent but still naive young man with little life experience. He told the Study he could not understand the idea of “heterosexuality.” To him it made no sense that anyone should be restricted to having sex with only one gender—as far as he was concerned, beauty was beauty, and love was love. He was attracted to both men and women; shouldn’t everybody feel that way? He was open about this idea with his friends and fellow students until he began to encounter resistance, and then significant prejudice, at which point he began to hide his sexuality. Soon after college, he married Maryanne, whom he deeply loved and who loved him, and they had kids and lived a full life together. But in 1978, after thirty-one years of marriage, Maryanne died of breast cancer, at the age of 57.

When the Study asked James why he thought their marriage had lasted so long, he wrote,

We survived because we shared so very much. She read important parts of good books to me. We talked of castles and kings, of cabbages, and many other things. We looked and compared notes on what we saw.… We enjoyed eating together, seeing places together, sleeping together.… Our parties, our best parties, were spontaneous ones that we created for just the two of us, often as surprises for each other.

Three years after Maryanne’s death, a Harvard Study interviewer visited James in his home. During the visit James asked the interviewer to follow him as he went into a brightly lit room chattering with birds. Beside the windows were a few cages, and in the middle of the room, several rope lattices and artificial trees. The birds alighted on him as he opened their cages and fed them. They were his wife’s birds, he told the interviewer, still so grief-stricken that he couldn’t manage to say her name. Asked about his current love life, he said that he’d had some short-lived relationships, that many people thought of him as gay, and while he wasn’t currently in a relationship, he hadn’t given up on the possibility. “I suppose eventually someone will come along and touch my heart,” he said.

As anyone who has loved another person knows, the pursuit of intimate connection is not without hazards: by opening ourselves to the joy of loving and being loved, we risk being hurt. The closer we feel to another person, the more vulnerable we become. Yet we continue to take that risk.

This chapter wades into the deep end of intimacy and the effect intimate connection has on well-being. We encourage you to see everything we offer in the coming pages through the lens of your own personal experiences, and to try to uncover some of the reasons behind both the successes and the challenges you’ve had in intimate relationships. As the lives of our Harvard Study participants show, recognizing and understanding your emotions, and how those emotions affect your intimate partner—the person beside you—can have both subtle and sweeping impacts on your life.

INTIMACY, AND ALLOWING OURSELVES TO BE KNOWN

We asked Study participants and their partners a set of questions about intimacy again and again over many decades. This allowed us to see each unique trajectory of feeling—affection, tension, and love—from a relationship’s beginnings to its very end. These relationships ran the gamut from brief and fiery to long and sleepy, and everything in between. Let’s look at one of those that’s in between:

Joseph Cichy and his wife, Olivia, married in 1948 and remained married until Olivia passed away in 2007 just after their fifty-ninth wedding anniversary. Their marriage is representative of a strong partnership, and the ways that two people can support each other over the duration of a life. But their partnership is representative for another reason, too: it was far from perfect.

Over the years, whenever the Study checked in with Joseph, he reported that he felt good about his life. He had a career he liked, three wonderful kids, and a “peaceful” relationship with his wife. In 2008, we asked their daughter, Lily, to reflect on her childhood and she told the Study that her parents were about as calm as a married couple could be. She couldn’t remember them having a single argument.

Joseph had given a similar account to the Study across many years. “I am as easy to get along with as anyone who ever lived,” he triumphantly told the Study in 1967 when he was 46 years old. He loved his wife, Olivia, just as she was, he said; there was nothing he would change about her. He gave his children the same respect he would give to anyone, offering guidance when they asked for it, but not trying to control them. In his work as a businessman, he did his best to listen to the perspectives of others before offering his own view of a situation. “The only form of persuasion that works is to empathize,” he said.

It was a philosophy that served Joseph well his entire life. He enjoyed listening to people and learning about their experiences. We’ve been making the case that understanding how others feel and think is beneficial to us in our relationships, and Joseph is a great example of this. But for everyone who was close to Joseph, this interest in people and ability to listen coexisted with a problem: he was afraid of opening himself to others, even the people he loved.

And this included his wife, Olivia.

“The greatest stress in our marriage isn’t conflict,” Joseph told the Study. “It’s Olivia’s frustration about my unwillingness to let her get inside me. She feels shut out.” She was honest with him about how much this concerned her, and Joseph was well aware of her concern, telling the Study on several occasions that Olivia often told him how difficult he was to truly know. “I’m self-sufficient,” he said. “My biggest weakness is not leaning on anybody. I’m just made that way.”

Joseph was tuned in enough to other people that he could see and articulate their difficulty with him, but he could never get past a core, deeply rooted fear that is not uncommon: he didn’t want to be a burden, or to feel anything but fully independent. Though he attended Harvard, Joseph came from humble beginnings, and told the Study that he learned the value of self-sufficiency as a child on his family farm, where he spent days on end operating a horse-drawn plow alone. His mother and father were busy with their own work on the farm, and Joseph was expected to take care of himself. As an adult he believed he should handle any problems he encountered—emotional or otherwise—on his own. He didn’t see anything wrong with that.

In 2008, his daughter Lily, who was in her 50s, told a Study interviewer that she still lamented this philosophy. Her father was always there for practical support when she needed him, and she felt she could count on him at any time of the day or night (and in fact, she did count on him; he helped her through a difficult marriage and some of the most trying times of her life). But she never felt that she fully knew him.

At the age of 72, when asked about his relationship to his wife, Joseph told the Study that the marriage was stable, but that there was also a sense of disconnection between them. “There’s nothing pulling us apart,” he said, “but we’re not bound together.”

Joseph had decided as a young man that in his relationships, two things were more important than anything else: keeping the peace, and being self-sufficient. It was important to him that his life and his family’s life be stable above all else. This wasn’t necessarily wrong; his life, by most measures, was a good one. He loved his family, and they were all very loyal to each other. Joseph was conducting his life in the way that felt safe, and to the extent his approach prevented strife, it worked for him. It’s not bad to have a marriage where there’s little disagreement. But are there costs to always keeping the peace? By being so protective of his inner experience, and so selective about what he shared—by not being daring enough to open himself up—was Joseph denying both himself and Olivia the full benefits of an intimate connection?

Many of us have someone like this in our lives; we should remember it’s not necessarily a sign that they don’t care. But Olivia, at least, felt a sense of incompleteness, because the keystone of intimacy is the feeling of knowing someone and of being known. In fact, the word intimacy comes from the Latin intimare: to make known. Intimate knowledge of another person is a feature of romantic love, but it’s also more than that. It’s a quintessential piece of the human experience, and it begins long before our first kiss, long before we consider marriage, in the very earliest days of life.

INTIMATE ATTACHMENT: THE STRANGE SITUATION

From the moment we are born we begin seeking close connections, both physical and emotional, to other people. We begin life as helpless creatures, dependent on others for our very survival. Almost everything we encounter as infants is intensely novel and potentially threatening, so it’s essential that we establish a strong connection to at least one other person from the very first days of life. Being close to our mothers or fathers or grandparents or aunties is comforting and provides a refuge from danger. As we grow, we can explore the world beyond our comfort zone knowing that we have a safe place to go if things get scary. The simplicity and clarity of the young child’s situation provides a great opportunity to observe the fundamentals of human emotional connection. This period of life vividly displays some core truths about close emotional bonds that are relevant for adults as well as children.

In the 1970s, Mary Ainsworth, a psychologist, designed a laboratory procedure to help reveal how babies respond to the world around them and the people on whom they are most dependent. It’s known as the “Strange Situation,” and it has proved so useful over the decades that it’s still employed in research today, more than fifty years later. The key elements of it work like this:

A baby, usually between 9 and 18 months old, accompanied by her primary caregiver, is introduced to a room with some toys in it. After spending a short time in the room interacting with the caregiver and playing with the toys, a stranger enters. At first the stranger minds her own business, lets the child get used to her presence, and then tries to connect with the baby. A short time later, the caregiver leaves the room.

Now the baby finds herself in a strange place, with a strange person, and no one with whom she feels close. Often the baby will immediately show signs of discomfort and begin to cry.

A short time later, the caregiver returns.

What happens next is a key reason for the experiment. The child has encountered a strange situation, experienced some stress, and now her caregiver has returned. The researchers have deliberately disrupted the infant’s sense of safety and connection—albeit briefly—and the child needs to reestablish these. How will she respond? The way the infant attempts to stay connected to the person on whom she depends for survival—her attachment style—is believed to reveal how the child views her caregiver and also herself.

A SECURE BASE

Each of us has a particular way of staying connected to a person we need. Attachment styles are relevant not just to understanding early childhood, but also to understanding how we manage relationships throughout our lives.

It is normal for children to get upset when a caregiver leaves, and in fact this is what the healthy, well-adjusted child does. When the caregiver returns, the child will immediately seek contact, and upon receiving it, calm down and return to a state of equilibrium. The child seeks contact during this “reunion” because she views her caregiver as a source of love and safety and also feels deserving of that love. A child who displays this sort of attachment behavior is considered securely attached.

But infants who feel less securely attached cope with that insecurity in two different ways: by expressing anxiety or avoidance. More anxious infants will seek immediate contact when the caregiver returns to them, but have trouble being soothed. Avoidant children, on the other hand, may appear on the surface to be unconcerned about the caregiver’s presence. They may show little outward distress when the caregiver leaves the room, and may not seek comfort when the caregiver returns. They sometimes even turn away from the caregiver during the reunion. Parents may take this to mean that the child doesn’t care. But appearances in such cases can be deceiving. Attachment researchers theorize that these avoidant children do care when the caregiver leaves, but they have learned not to make too many demands on their caregiver. They do this, according to the theory, because they’ve sensed that expressing their needs may not result in receiving love, and may also drive the caregiver away.

In real life, children encounter variations on the Strange Situation repeatedly—when they’re dropped off at daycare and then picked up at the end of the day, for example—and each of these encounters shapes their expectations about future relationships. They develop a sense of how likely it is that others will be helpful, and also a judgment about how deserving they are of support.

Adult life is, in some fundamental ways, a real-world, highly complex version of the Strange Situation. Like every child who has been separated from their parent, each of us longs for a sense of security, or what psychologists call a secure base of attachment. A child may feel threatened because her mother is not in the room, and an adult may feel threatened by a frightening health diagnosis; both benefit from a sense that someone is there for them.

But attachment security exists on a spectrum for adults as well, and many of us are not fully secure in our attachments. Some of us may cling to others during times of stress yet have difficulty finding the comfort we seek, while others, like Joseph Cichy, may avoid closeness because we fear, deep down, that if we become a burden to others, we will drive them away. Or we may not be convinced that we are fully lovable. And yet we still need connection. Life becomes more complex as we age, but the benefits that come from having secure connections continue through every phase of life.

Henry and Rosa Keane, from Chapter One, are a shining example of two people with secure connections. Every time they faced a difficulty together—from one of their children contracting polio, to Henry being laid off, to the task of facing their own mortality—they were able to turn to each other for support, comfort, and courage.

The sequence for both babies and adults is often similar: a stress or difficulty disturbs our sense of security, and we seek to restore that sense. If we’re lucky we are able to do this by gaining comfort from those who are close to us, and we return to equilibrium.

In our last interview with them, sitting at their kitchen table, Henry and Rosa kept physically reaching out for each other, especially when answering difficult questions about future health challenges and their own mortality. Through most of the interview, they were holding hands.

That simplest of gestures—holding a partner’s hand—is a helpful portal into the world of adult intimate attachment. In the Strange Situation, when a securely attached child seeks her caregiver and is comforted by a hug, there are physiological and psychological benefits. Her body and her emotions are calmed. Is the same true for adults? What’s happening exactly when someone holds our hand?

LOVING CONTACT: THE EQUIVALENT OF A DRUG

James Coan ventured into the world of attachment research by accident. He had wanted to know what was happening in the brains of people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (a mental health condition characterized by flashbacks, nightmares, and worries about a traumatic event), and he was scanning their brains for clues. With a better understanding of their brain activity, he hoped, new treatments could be devised and their suffering could be eased. One of his study participants happened to be a Vietnam War veteran with intense combat experience who refused to participate in the research without his wife in the room. Coan was eager for his participation and was happy to make accommodations that allowed the study to continue, so the man’s wife sat beside him while he lay in the fMRI (brain scanning) machine.

MRI machines can be loud, and when the test began the man became agitated and didn’t want to continue. His wife, sitting beside him, sensed his agitation and instinctively took his hand in hers. This had a calming effect on him, and he was able to go on.

Coan was intrigued by this effect, and when the study was over, he developed a new brain imaging study to see if he could find some neural evidence for what had happened.

Participants in the new experiment were put into the fMRI machine and shown one of two slides. A red slide meant there was a 20 percent chance they would receive a small electrical shock. A blue slide meant they would not receive a shock.

The participants were divided into three groups: the first group had no one in the room with them during the experiment. The second group held the hand of a complete stranger. The third group held the hand of a spouse.

The results were crystal-clear: holding hands with someone they felt close to calmed the activity in the fear centers of participants’ brains, and diminished their anxiety. But perhaps most remarkable, holding hands with someone they felt close to actually diminished the amount of pain participants said they felt when they received a shock. There was also a benefit to holding the hand of a stranger, but the effect was so pronounced for intimate partners (particularly those in more satisfied relationships) that it led Coan to conclude that holding a loved one’s hand during a medical procedure had the same effect as a mild anesthetic. Study participants’ relationships were affecting their bodies in real time.

MORE THAN A FEELING

Relationships live inside of us. The mere thought of a person who is important to us can generate hormones and other chemicals that travel through our blood and affect our hearts, our brains, and numerous other body systems. These effects can span a lifetime. As we noted in Chapter One, using data from the Harvard Study, George Vaillant found that marital happiness at age 50 was a better predictor of good physical health in late life than age 50 cholesterol level.

Coan was able to analyze the effect of intimate connection on a person’s brain in the lab, but we obviously can’t (yet) put ourselves into an fMRI machine while we’re on a first date, or when we’re having an argument with a partner in a parking lot. Luckily, at the very root of all intimate attachment, regardless of our age, there is a different kind of diagnostic tool that each of us can access just by paying attention:

Emotion.

In any situation in life, emotions are a signal that there are matters of significance to us at play, and they are especially revealing when it comes to intimate relationships. If we take some time to pause and examine that seemingly simple thing, how we feel, we can develop an invaluable life tool: the ability to look beneath the surface of our relationships. Our emotions can point us to hidden truths about our wishes and fears, our expectations about how others should behave, and the reasons we view our partners the way we do.

Imagine it this way: when scuba divers descend into a body of water, they have depth indicators on their wrists. But they can also feel the depth in their bodies. The deeper they go, the more pressure they feel.

Emotions are a kind of depth indicator for a relationship. Most of the time we are swimming near the surface of life, interacting with our partners and going about the daily business of living. The underlying emotional currents are buried a bit deeper, in the dark of the water. When we experience a strong emotion, positive or negative—a sudden welling-up of gratitude, or a surge of anger at being misunderstood—it’s an indication of something deeper. If we make an effort to pause in these moments, to watch and interpret, as we’ve suggested in our W.I.S.E.R. model of interaction (Chapter Six), we can begin to see more clearly the things that are important to us, and also what’s important to our partners.

NURTURING A BEDROCK OF EMPATHY AND AFFECTION

How important are the emotions that we feel (and express) during interactions with our partners? Can emotions indicate the strength of connection, and the likelihood of a lasting partnership?

We investigated the link between emotion and relationship stability in one of our earliest joint research studies. We brought couples who were married or living together into the lab and videotaped them for eight to ten minutes as they discussed a recent upsetting incident in their relationship. Later the videos were rated for how much each partner expressed specific emotions (for example, affection, anger, humor) and behaviors (for example, “acknowledges partner’s perspective”).

We specifically asked research assistants who did not have extensive training in psychology to rate the emotions in these videos. Would these untrained observers’ natural human ability to recognize how others are feeling be useful in predicting stability in relationships?

Five years later, we checked back with the couples to see how they were doing. Some were still together, some were not. When we set their relationship status beside our research assistants’ ratings of emotions in their earlier interactions, we found that the ratings predicted with close to 85 percent accuracy which couples had stayed together. This is consistent with many other studies showing that emotions between partners are a critical indicator of whether intimate relationships thrive or fail. The fact that raters with no special knowledge of psychology could accurately predict relationship strength was significant because it showed that most adults have a facility to accurately read emotions. Most of the raters had not yet experienced deep, longer-term relationships, yet when they looked closely, they could sense important, sometimes subtle emotions and behaviors in the couples. Emotions drive relationships, and noticing them matters.

Not every type of emotion is equally predictive of the health of a relationship, however. Some are particularly important, and in our study, two categories of emotion stood out:

Empathy and affection.

The men and women who expressed more affectionate emotions while they were discussing something upsetting with their partner were more likely to be together five years later. Empathic responses from the men were also important. The more that men were tuned in to their partner’s feelings, the more they showed interest in understanding their partner, and the more they acknowledged their partner’s perspective, the more likely the couple was to stay together. These findings, along with our findings about the importance of empathic effort (discussed in Chapter 5), point to an important idea about intimate relationships: if a couple can cultivate a bedrock of affection and empathy (meaning curiosity and the willingness to listen), their bond will be more stable and enduring.

A FEAR OF DIFFERENCES

All kinds of things can cause strong, challenging emotions in intimate relationships. Even positive emotions can be challenging. A great love, because of its importance to us, can become plagued by a great fear of loss.

But one of the most common reasons for strong emotions in a relationship is simple differences between partners. Where there is difference, there may be disagreement, and where there is disagreement there is often emotion.

When differences first arise, they can be alarming. After the initial excitement and euphoria of a new relationship begins to wane, you might start to notice things about your partner that worry you. Sometimes it might be Big-D Differences (like whether or not to have kids) that warrant consideration of whether the relationship is right for both of you. But often it’s little-d differences that seem big because of the adjustments they require. Maybe one of you likes to joke around in times of stress and the other finds nothing funny about hard times. Or one of you loves to explore new restaurants and the other prefers to cook at home.

When you begin to discover these differences, it’s easy to feel threatened. If you’re married or living together, you might feel as though the specific life you’ve always imagined is under threat, but you’ve come too far to turn back. You might feel trapped, and begin to have thoughts like, My partner is:

Selfish

Ignorant

Immoral

Damaged

… and the differences can come to look like problems that are hardwired by background or family. This can seem to be evidence of how incompatible the two of you are.

Psychologist Dan Wile wrote in his book After the Honeymoon:

After the honeymoon. The very words carry a burden of sadness, as if for a short while we lived in a golden trance of love, and now we’ve been jolted awake. The fog of early infatuation has lifted and we see our partners for who they are.… Immediately comes the thought, “Oh no! Is this the person I’m supposed to spend the rest of my life with?”

Confronted with these emotions, we often (and understandably) think the goal should be to avoid or reduce differences. Joseph Cichy was a master at minimizing difficulties. He lived his entire life doing his best to avoid conflict and smooth over any cracks. And in terms of diminishing conflict, it worked. But the result was a marriage with less emotional closeness, less intimacy.

So the question becomes, if a smooth relationship with no conflict is not the path to rich and fulfilling intimacy, but conflict often causes stress, what do we do?

THE DANCE

Early in their marriage, Bob and his wife, Jennifer, used their weekly date night to go to a ballroom dancing class. Most of the other couples were engaged and taking the class to help them on their wedding day. During one class Jennifer, who is a psychologist, wondered: Could each couple’s way of dancing together be a window into what their relationship was like? As with new challenges in relationships, new dance moves are sometimes awkward at first, and it takes couples time to learn the steps and to adjust to and accommodate each other. One partner is usually a faster “stepper” or more of a natural than the other, but both make mistakes, both are learning. Could their dancing indicate which couples were capable of tolerating and forgiving mistakes? Could their style of resolving problems in the dance predict whether they’d still be together in five years?

Just as with dancing, the old adage that you have to learn by doing is especially apt when it comes to relationships. There is give-and-take, flow and counterflow. There are routines, steps, and improvisations. Most importantly, there are mistakes and missteps. No couple is going to be Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers the first time they take the floor together. (Even Fred and Ginger needed a lot of practice!) Both partners must learn as they go. These missteps are not failures or signs that dancing together is impossible. Instead, they are opportunities to learn; step here instead of there. My partner wants to go this way—I’ll go with him. Now I would like to go that way—he’ll have to learn to come with me. Yes, we notice the mistakes and those moments when we are not in sync. But the important thing is how both dance partners respond.

The same is true in life. In the end, what matters most are not the challenges we face in relationships, but how we manage them.

UNDERVALUED OPPORTUNITIES

One thing both of us, Marc and Bob, know from decades of doing couples therapy is that people in intimate relationships often overlook the opportunities presented by disagreements.

It happens all the time: a couple shows up for their first session, and one partner has a very clear idea of why they are there. It often involves pointing a finger at the other person:

He has trouble letting things go.

She needs to work on her anger issues.

He doesn’t do his share around the house.

She never wants to go out, but I don’t like sitting around.

He’s obsessed with sex (or he’s not interested in sex).

Whatever the “problem” is, the implication is clear: my partner needs to be fixed. But in reality, there’s almost always a deeper, more complex tension within the relationship that the couple has not acknowledged. Discovering that tension usually requires both self-reflection and conversation.

In couples therapy, we assume that there will be disagreements and differences, and we encourage couples to recognize and attempt to understand them. Disagreements, and the emotions that come with them, are opportunities to revitalize a relationship by revealing those important truths hidden below the surface.

Two lives, in all of their complexity, are bound to include differences that don’t quite fit together. Maybe you feel the need to keep things clean and a pile of dirty dishes causes a flash of frustration, or your partner gets angry at you about your attention to your smartphone, or maybe one of you is often running late and that causes arguments.

“You never put the cap back on the toothpaste tube!” one partner might complain, with an emotional weight that doesn’t seem to match the circumstances.

The intense feelings that emerge in recurring arguments, however trivial, often come down to one of a few common, but profound concerns. See if any of these ring a bell:

You don’t care about me.

I’m working harder at this than you are.

I’m not sure I can trust you.

I’m afraid I’m going to lose you.

You don’t think I’m good enough.

You don’t accept me for who I am.

Sifting through the emotions of a disagreement to uncover these fears and worries and feelings of vulnerability—both our partner’s and our own—isn’t always easy. First we have to allow for the possibility that we are missing what’s really going on beneath the surface. Because we have an instinct to protect ourselves, we have a tendency to jump to conclusions without realizing that’s what we’re doing. Just as we flinch or throw up our hands when a physical object is hurled at us, we tend to flinch and pass judgment when a heavy emotion comes our way.

The cap on the toothpaste tube would never bother me—why does it have to bother you? You’re too sensitive!

And just like that, rather than investigating the disagreement and the emotions that come with it, we’ve taken a hard stance, passed judgment, and decided that the problem is our partner’s oversensitivity. This kind of judgment happens instantly in all kinds of situations, from “trivial” disagreements to the biggest issues of love and connection.

Joseph Cichy, for example, couldn’t see the full extent of his wife’s experience because he was too immersed in his own interpretation. He understood that his resistance to being open bothered her, but he’d already decided that his understanding was the right one. In his mind, he was saving her the trouble of hearing about his personal feelings. Sharing his emotions, he thought, would endanger his peaceful relationship with his wife, and he didn’t want to lose her. But in an effort to protect against that vulnerability, he was contributing to the vulnerability that his wife felt. After all, the person she was closest to in the world did not seem to need her as much as she needed him.

He never asked the question, What would it mean for our relationship if I shared more of my feelings?

We all have our own vulnerabilities, those fears and worries that cause us to react to disagreements by turning away from them to protect ourselves. These emotions are not easy to face, but the disagreements we have with our partners have the potential to reveal them to us.

MUTUAL VULNERABILITY: A SOURCE OF STRENGTH

When our Second Generation participants spoke of the lowest moments in their lives, a large proportion of those moments were related to intimate relationships. Deep, intimate connections are by their nature incredibly vulnerable situations. When two people who are intimate are in harmony, the effect can be exhilarating, but if the relationship falters, the result can cause intense emotional pain, feelings of betrayal, and critical self-examination. As one of our Second Generation participants, Aimee, told the Study:

My first husband is from Texas and we moved there after meeting in Arizona. We lived in a small town raising our daughters, but my husband worked in Dallas, so he had to spend nights there occasionally. A friend called me one night and said he saw my husband being intimate with another friend of ours. My husband admitted to an affair. It destroyed me, but I also felt sure that I could keep going on my own. My daughters and I moved back to Phoenix and lived for two years with my aunt and her husband. As I examined possible reasons for the breakup, I began to wonder whether I was just less fun, less exciting after our move to Texas. It was something of a blow to my self-confidence as a young woman. Could I be everything to someone, or was I lacking some essential “wife” feature?

To have an intimate partnership with someone is to expose ourselves to risk. When we trust someone enough to build a life around our relationship with them, that person becomes a kind of keystone. If our connection to them feels precarious, the entire structure of our lives may feel more precarious, too. That can be a frightening situation. Couples often share not just finances and resources, but children, friends, and important connections to each others’ families. Worries about the relationship failing and causing a domino effect on the rest of our lives can be overwhelming, and can seep down into our perception of ourselves. We may wonder, as Aimee did, about our own fitness as a partner, and if we’re even capable of fulfilling another person’s needs.

If we’ve been hurt before, and most of us have, we might be reluctant to fully trust an important relationship. Even if we’ve been with someone for decades, we can still feel a need to protect ourselves.

Mutual, reciprocal vulnerability can lead to stronger and more secure relationships. The ability for partners to trust and be vulnerable with each other—to pause, notice their own and their partner’s emotions, and comfortably share their fears—is one of the most powerful relationship skills that a couple can cultivate. It can also relieve a lot of stress, because both partners can get the support they need without having to muster energy in an attempt to be stronger than they really are.

If we do manage to cultivate a strong and trusting bond, we’re still not out of the woods, because even the best relationships are susceptible to decay. Just as trees need water, intimate relationships are living things, and as the seasons of life pass they can’t be left to fend for themselves. They need attention, and nourishment.

THE ENDURING INFLUENCE OF INTIMATE PARTNERSHIPS

Love seems the swiftest, but it is the slowest of all growths. No man or woman really knows what perfect love is until they have been married a quarter of a century.

Mark Twain

Amazing things can happen when a relationship is nurtured over decades. On the other hand, if our most important relationship is neglected, life can devolve into isolation and loneliness.

For illustrations of those two paths, let’s go back to Leo DeMarco and John Marsden, two of our First Generation Harvard Study participants. Leo is one of the Study’s happiest men, and John one of its unhappiest.

Leo’s relationship with his wife, which spanned nearly his entire adult life, contained much of what we’ve been saying is key to satisfying relationships: affection, curiosity, empathy, and a willingness to face toward challenging emotions and problems, rather than avoid them.

For example, in 1987, Leo’s wife, Grace, told the Study that they had some areas of disagreement, including how much time they should spend together, how much sex they should be having, and how often they should be away from home.

When they disagreed, what did they do? They talked about it, she said. They got to know what the other was thinking, and either accepted the difference or worked something out. And just as importantly, they scaffolded this process with affection.

John Marsden’s wife, Anne, had different responses to the same questionnaire. She often disagreed with John, she said. But what was most corrosive for their relationship was the lack of affection between them. She believed there should be more—and he also believed there should be more. But they could not figure out how to get there and they didn’t talk about it. He rarely confided in her. She rarely confided in him. Were there times, the Study asked, when they were apart and she wished they were together? “Almost never,” she said.

The different emotional patterns in each of these marriages stretched through decades of Leo’s and John’s late lives.

In 2004, we videotaped an interview with Leo in his living room. At one point, the interviewer asks:

“Can you think of five words that describe your relationship with your wife?”

After some stopping and starting, and a few attempts to choose the right words, Leo puts a list together:

Comforting

Challenging

Feisty

Pervasive

Beautiful

Around the same time, in a different part of the country, John Marsden was interviewed in his personal study. In the video he is surrounded by oak shelves full of books, and a bright window to his right looks out on a garden. He’s asked the same question—“Can you think of five words that describe your relationship with your wife?”—and he shifts in his chair.

“This is um, this is a required question I suppose?” John asks.

“I wouldn’t say it’s required,” the interviewer responds.

“I’m not sure I could come up with much.”

“Just do your best.”

John looks around the room and then methodically recites this list:

Tension

Distant

Dismissive

Intolerant

Painful

Most of us have relationships that fall somewhere in between—or even vacillate between—these two extremes. But in these two relationships we see a vivid contrast in the quality of intimacy—a contrast between facing emotional challenges and avoiding them, between affection and distance, between empathy and indifference.

Recall for a moment the Coan handholding study and the Kiecolt-Glaser wound-healing study, which are among the many studies that have shown two crucial findings: First, that the presence of a trusted, intimate partner decreases stress, and second, that stress can affect the healing ability of our bodies. Of course, we can’t know exactly how much of Leo’s and John’s late-life health was attributable to the amount of love they felt in their closest relationship, but we do know that Leo was physically active deep into his life, and that John was very ill for many years. Their relationships are not the only reason for that, but the love that Leo shared certainly increased his chances for enduring health, and the pain and distance that John felt in his closest relationship could not have helped him. The same is true for their wives. Over the course of these couples’ lives, their relationships dramatically affected their happiness, life satisfaction, and almost certainly their physical health. It’s a story that appears in the Harvard Study again and again.

INTIMACY OVER THE COURSE OF THE LIFESPAN

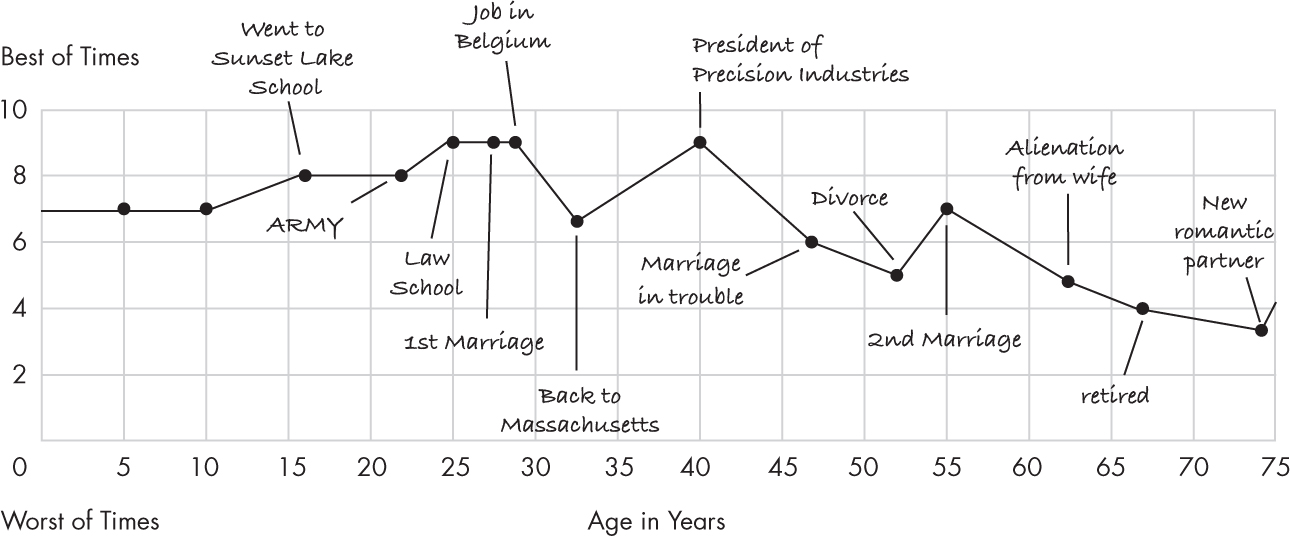

The graph above was made by a First Generation Study participant, Sander Meade, as he looked back on his life when he was in his late 70s. The scale on the left-hand side of the graph represents a rating from the “Best of Times” to the “Worst of Times,” and the bottom scale shows a participant’s age at the time of each rating. Similar to other participants, many of the big shifts in Sander’s life satisfaction coincided with changes in his relationships: age 47: “marriage in trouble”; age 52: “divorce”; age 55: “2nd marriage”; and so on.

Sander’s map of his life reflects a key lesson of the Harvard Study and many other research projects: relationships (and especially intimate relationships) play a crucial role in how satisfied we are at any particular moment in life.

Life changes of all kinds can cause stress in our intimate partnerships. Even positive changes like getting married can be stressful. Young couples, for example, are often surprised by the relationship challenges that arise when they become parents. What was supposed to be a joyous beginning of family life becomes a minefield of new disagreements and difficulties compounded by exhaustion and worry. New parents often start to have arguments they’d never had before. They are more stressed, and they often feel unsupported by their partners.

This is perfectly normal. Many studies, including our own, show that there is often a decline in relationship satisfaction after the birth of a child; it doesn’t mean the relationship is in trouble. Caring for an infant is a major challenge, and much of the time and attention that was once devoted to the couple’s relationship must be diverted to the child. So it’s natural for couples to struggle somewhat after they have children.

Our careful tracking of relationships across the lifespan in the Harvard Study points to that moment when kids leave the nest as another key turning point in intimate relationships. There are lots of anecdotes about a potential “empty nest boost” in marital satisfaction, but our Study is one of the few with the data to track relationships across decades, including this transition point. Examining the marriages of hundreds of couples, we find that around the time the last child turns 18, partners commonly begin to experience a noticeable increase in relationship satisfaction.

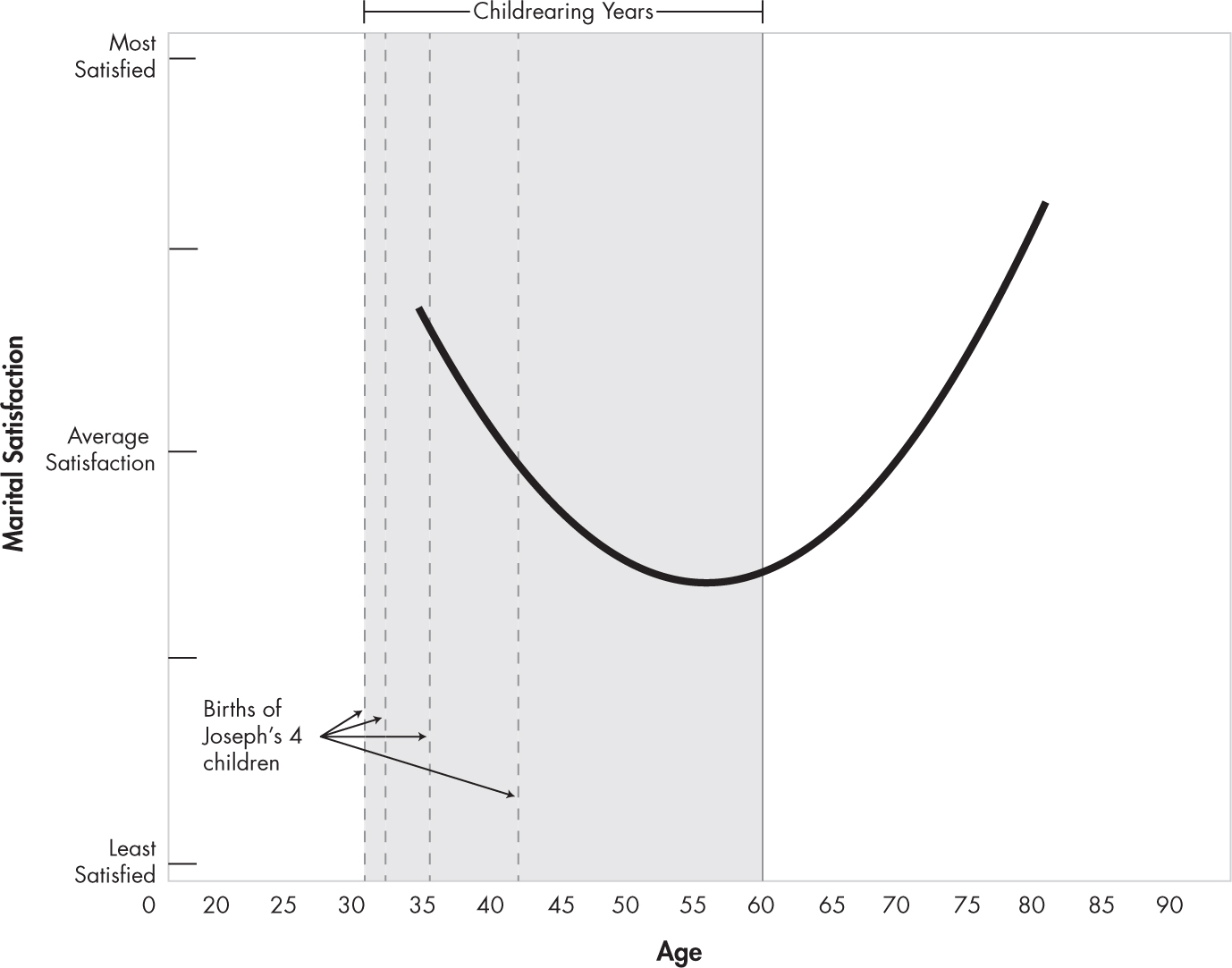

Even Joseph Cichy, who did not have the closest marital relationship, experienced this boost. Using data from the Harvard Study, we can plot lifetime trajectories of marital satisfaction, which often look similar to Joseph’s (below). Each vertical dotted line represents the birth of a child, the gray shading represents the time when Joseph and Olivia were raising children under the age of 18, and the dark vertical line represents the year the last child—his daughter Lily—went off to college.

For the men in the Study, this empty nest boost has significance beyond a couple’s marital satisfaction. In fact, we found that the size of the empty nest boost (it varies across couples) predicted how long these participants would live. The larger the boost in relationship satisfaction after the kids left home, the greater their longevity.

Intimate connections become particularly important in late life. As we age, we encounter more physical challenges, and we need to be able to depend on each other in new ways. When male and female Study participants were in their late 70s and early 80s, those who were more securely attached to each other reported better mood and fewer disagreements. Two and a half years later, when we checked back in, those securely attached individuals reported feeling more satisfied with life and less depressed, and the wives showed better memory functioning—another piece of evidence suggesting that relationships have an impact on our bodies and brains.

JOSEPH CICHY’S MARITAL SATISFACTION ACROSS TIME

When we look at the spectrum of how individuals in intimate relationships adapted to change and leaned on each other in old age, Leo DeMarco and John Marsden are again at opposite ends. In the interviews we conducted when they were in their 80s, we asked both of them this question:

When you are upset emotionally or sad or worried about something that is not related to your wife, what do you do?

Leo’s answer was characteristic of someone who feels the warmth of a secure attachment with a partner: “Go to her. Talk with her,” he said. “It’s very natural. I certainly don’t keep it to myself. She’s my confidant.”

John’s answer, on the other hand, was emblematic of someone who has learned to cope with vulnerability by avoiding dependence on a partner: “I keep it to myself,” he said. “I tough it out.”

Late life is a time that brings physical challenges and sickness to many. For some of us that means becoming caregivers again (or for the first time), and for some of us that means learning how to accept care. Feeling secure in an intimate relationship means both being available to help a partner and being able to depend on a partner in a time of need. It can be a shock to realize we can no longer reach our own feet to tie our shoes, or that we need help standing up out of a chair. Having a person beside us with whom we are able to share our deepest vulnerabilities can be the difference between a sense of despair and well-being. When we’re sick, we also often need someone to act as our advocate—a spokesperson, an organizer, someone to be our hands or eyes or ears… or even our memory. On the other side, being that advocate certainly involves self-sacrifice, but it can also be a source of satisfaction.

To put it simply: couples who are able to face stresses together reap benefits in health, well-being, and relationship satisfaction.

A FINAL NOTE ABOUT OUR “BETTER HALVES”

In the 1996 romantic comedy Jerry Maguire, Tom Cruise famously echoes Plato’s notion of love, when he announces to Renée Zellweger, “You… complete me.”

While the feeling that our partners can be our “better halves” still rings true, the practical reality is that very few intimate relationships provide both partners with everything they need. Expecting to find completion in our partners can lead to frustration and even the dissolution of otherwise positive relationships.

In his book The All-or-Nothing Marriage, psychologist Eli Finkel argues that our expectations of marriage have become unrealistic—particularly in the U.S. and other Western industrialized countries—and that this is part of the reason divorce rates rose sharply in the twentieth century. Before 1850 or so, marriage was essentially a partnership for survival. Between 1850 and 1965, the focus of marriage shifted to include enhanced expectations about companionship and love. In the twenty-first century, a number of factors in the economy and culture have converged in a way that has piled even higher expectations on intimate relationships. People often are less engaged in their local communities, and they relocate more for work. This greater mobility means that fewer people are living near extended family. Many do not stay in one place long enough to build stable groups of friends. Who do we expect to fill all of these gaps? The person beside us.

Without realizing it, many of us expect our partners to provide money, love, sex, and to be our best friends. We expect them to provide counsel and conversation and to make us laugh. We want them to help us become our best selves. We not only ask our partners to do these things for us; we also expect to provide these things for them. A lucky few may find themselves in relationships where these high expectations are met reasonably well. In most relationships, it’s too much to ask.

How do our close relationships get weighted down with so much expectation? Sometimes the reason has less to do with the relationship and more to do with waning connections in other parts of our lives. If we’re no longer having the kind of fun we can only have with a group of friends or family members who know us well, or we’ve stopped pursuing our personal interests, hobbies, and passions, we might turn to our partner to fill those needs. The intimate relationship becomes like a sponge, soaking up whatever failed expectation happens to be lying around. Suddenly we’re finding fault with the person beside us when it’s the rest of our lives and our other relationships that need attention. These expectations can take a toll.

The research is clear: intimate relationships can be an incredible source of sustenance for our minds and bodies. But there are limits to what they can do. If we want to give a relationship the best chance of success, we have to support it by sustaining other parts of our lives. Our partners may in fact be our better halves, but they can’t, by themselves, make us whole.

THE PATH AHEAD

There is no remedy for love but to love more.

Henry David Thoreau

As you think about how the things we’ve discussed in this chapter map onto your own life, consider using the following practices to nudge a relationship in the direction you’d like it to go.

“Catch” your partner being kind. What was the last thing your partner did that you felt grateful for? A dinner he made? A backrub she gave you? Or maybe there was a moment you were impatient with your partner, but he didn’t hold it against you, and you appreciated that.

Take note of that small act. Research points to the benefits of keeping a gratitude diary to record and solidify the things we feel grateful for, but even simply noticing and calling to mind the good, little things your partner does can have a positive impact. This is a simple but powerful way for us to “catch” our partners being kind rather than falling into the common trap of giving more attention to disappointments. Expressing our gratitude to our partner increases the impact further. There are reasons we connected to our partners in the first place, and reasons they make our lives better now—it’s good to remember those reasons (and to mention them!). It feels good to be appreciated.

Step out of old routines. As we go about the business of life, our relationships can begin to feel like they are stuck in repetitive cycles that are not exciting.

Every night: dinner and TV.

Every morning: coffee and oatmeal.

Every Sunday: mow the lawn, go to the grocery store, cook the same dinner.

Try something different! Make a plan to surprise your partner with breakfast in bed. Maybe you haven’t walked around your neighborhood together in years—after dinner instead of falling into the grooves of your usual routine, take a stroll and see what’s out there. Plan a weekly date night and take turns choosing what you will do (and maybe surprise your partner with a new activity if a surprise would be welcome).

We all fall into habits and routines. That’s normal. But often they become so rote that we cease to really notice our partners as we cruise through the day. Breaking these routines alerts our minds to novelty, and this helps us recognize and appreciate our partners in new ways. It also signals to our partners that they are important to us.

And there’s always dance class…

Try the W.I.S.E.R. model (squared). When disagreements arise, consider using the W.I.S.E.R. model (from Chapter Six), and sharing the techniques with your partner. The watch and interpret steps are especially useful in intimate relationships. Taking extra time to watch ourselves and our partners in an emotional situation can help us see with greater clarity the reasons behind the emotions we are feeling. Introducing some stillness into a moment of turmoil can help us clear the muddy water below the surface of our relationship.

So when you bump up against something about your partner that bothers you, before reacting, pause to watch, and take note of your reactions and what you are thinking.

Then interpret your feelings and try to make sense of what’s going on. Ask: Why is this issue important to me? What exactly is my view? Where does it come from? Is this something I learned from my family growing up? Something I learned from previous relationships? Something that was emphasized in my religious training?

Then, the harder part: try to step into your partner’s shoes. Why is my partner having such a strong reaction, behaving in this particular way, thinking this particular thing? Why might it be important to my partner and where might my partner have learned this? Where is it coming from?

Sometimes it’s difficult to start conversations about challenging topics, and difficult to move interactions in a new direction. The waters of old grievances tend to run deep. Just telling your partner that the topic makes you anxious is a good start. There are a few additional techniques that might be useful in that case.

One is known as “reflective listening.” It helps us make sure we’re hearing correctly what our partner is trying to say, and it shows that we care, that we are trying to empathize. It works like this:

First, listen without commenting.

Then, try to communicate what you’ve heard your partner say without judgment (this is the hard part). You might begin with something like: What I’m hearing you say is ___. Is that right?

A second technique that is helpful in its own right and can make reflective listening even more valuable is to offer some understanding of your partner’s reasons for a feeling or behavior. The goal is not to point out your brilliance and ability to see things your partner cannot, but to let your partner know that you see them. You want to communicate that it makes sense that she feels this way or that he is behaving in that way, and to nurture that bedrock of empathy and affection that research has shown to be valuable. For example, you might say, It makes sense that you feel so strongly about this… and then continue with something like: since you care so much about being kind. Or: … since this was the way you’ve described things happening in your family growing up.

A third useful practice is to try to step back a bit from the conversation, a practice that psychologists call “self-distancing,” and look at your experience as if you are watching someone else. You might notice the thoughts that this person (i.e., you) is having, and recognize them as fleeting thoughts that may shift. This is a technique that shares much in common with mindfulness approaches, and the psychologists Ethan Kross and Ozlem Ayduk have done a lot of research showing its utility.

Together these practices may help you to get started with challenging conversations and hang in there emotionally when things get tough, to slow down, and to show your partner that you’re trying to understand.

Don’t be afraid to come up with some of your own practices that work in your particular relationship. When you feel yourself getting angry or feeling defeated or scared, remember that it’s a signal. Reach out to your partner in those moments. Try to see beneath the surface, and remember that just like you, your partner is also fighting battles.

We each bring our own particular strengths and weaknesses into a relationship, our own fears and desires, enthusiasms and anxieties, and the dance that results will always be unlike any other.

“We don’t harbor resentment,” Grace DeMarco told the Study in 2004, referring to her relationship with Leo. “When we’re pushed hard enough, we really say what we feel, get it out in the open. You can be very different but still respect that difference. And we need the difference, actually. He needs the lightening up and I need the settling down.”