Chapter 11

Adding Interest through Framing and Formatting

In This Chapter

Creating a compositional frame within a frame

Formatting your images according to your subject, message, and environment

When you put a photograph in a picture frame, you send potential viewers a clear message. If a frame could speak, it would say, “Hey, look in here.” A frame shows viewers exactly where to look and then keeps their eyes inside its borders. You can get that same effect by composing your images so that elements within it surround your subject and ensure that the viewers’ eyes go directly where you want them (and then stay there). To make that frame effective, you have to study your scene, determine your subject and which elements successfully frame it, and then compose the image accordingly.

An interesting composition is one that fulfills two jobs: It provides a framed image that’s aesthetically pleasing, and it tells a story based on the relationships of the elements included in the frame. Ideally, a composition is interesting enough to keep a viewer’s attention for more than just a few seconds. When viewers can explore compositional elements that fit perfectly in your frame and interact with each other in a harmonious way, they’re likely to be captivated by your image.

In this chapter, I help you gain and keep your viewers’ attention by guiding you in an exploration with compositional framing techniques. I also provide information on determining whether a horizontal or vertical format would best suit your subject and message in a particular scene.

Making the Most of Framing

Your frame is the entire rectangle that contains your scene. Within it you may create an additional compositional frame — certain elements that surround the subject. Serving as the outer rim of your composition, a compositional frame keeps viewers’ eyes from leaving the image and directs them to the scene’s important components. You can make a compositional frame from almost anything, as I highlight throughout this section.

Photographers commonly use trees to frame a subject. Tree limbs bend and twist into dynamic shapes that seal off the edges of your frame. Often, photographers will pay particular attention to trees when shooting exteriors of buildings and structures. I’ve seen everything from small cottages to the Eiffel Tower framed by trees. In Figure 11-1, I used trees in the background as a compositional frame to surround my subject.

Figure 11-1: A basic example of a compositional frame.

Find the right perspective. Perspective is the most important element when creating a successful compositional frame. Consider a tree in comparison to the Eiffel Tower, for example. If you’re far away from the tree itself, the Eiffel Tower dwarfs the tree. From that perspective, the tree serves as a foreground element and can’t frame the structure. But if you move your camera very close to the tree, it appears taller than the Eiffel Tower. This perspective enables you to compositionally frame your very large subject; it also gives depth to your composition by highlighting distance between elements within the image. When scanning a scene for the best perspective, move forward and backward to search out elements that you can use to frame it.

Use the appropriate depth of field. Depth of field controls how much of your scene is in focus. If your compositional frame provides information that’s essential to your message, you may want to keep it sharp enough to reveal some of its details. If your compositional frame works only to frame the image, you’ll likely want to let it go blurry so it doesn’t draw any unnecessary attention but provides a realistic sense of depth. Chapter 7 goes into more detail about depth of field.

Avoid merging shapes and lines. Mergers are shapes and lines that intersect in awkward ways. If a compositional frame merges with your image’s subject, make sure it doesn’t affect the shape or appearance of the subject. For example, you probably don’t want to block a person’s face with a tree branch when taking her portrait. I discuss mergers further in Chapter 9.

In the following sections, I explain how the compositional frame can provide a sense of three-dimensional space in your images, how to get creative when including compositional frames, and why a viewer will look at an image longer when this technique is used successfully.

Giving your image a sense of depth

Visual depth causes the appearance of three-dimensionality and gives viewers a more enjoyable visual journey through an image. The simplest way to add depth to your composition is to include elements in the foreground.

In Figure 11-2, I positioned the rocks in the foreground at the front edge and left and right sides of the frame. They don’t come into the frame enough to compete with the waterfall, which is the subject. Instead, they work to lead viewers to the waterfall. They serve a double purpose by showing the environment around the waterfall and leading viewers’ eyes to the subject.

Figure 11-2: Foreground elements can be used to lead viewers and keep them from exiting the bottom of the frame.

A shallow depth of field can enhance the sense of distance in your image. (Chapter 7 tells you more about depth of field.) Your eyes can focus on only one distance at a time. The closer two objects are, the more likely you can see them both clearly without switching back and forth between one and the other. So, when you focus on something distant, the object right near you becomes a vague blur in your peripheral vision.

Adding interest by getting creative with your compositional frame

A compositional frame doesn’t have to be as obvious as a tree or rock in the foreground. You can use anything to frame an image — any object, shadow, or reflection — and it can be in front of or behind your subject. Be as creative as you can with your frames. Look for shapes, tones, colors, and forms in a scene that seem to create a border for your subject, and allow them to become part of the scene rather than just existing at the edges. Also try to incorporate a compositional frame into the image subtly.

Sometimes a compositional element that frames an image serves only one purpose — to be a frame. This isn’t true in Figure 11-3, which has many compositional ideas happening at once. It has a frame that’s also quite possibly the subject of the image. You could say that the birds or the sunrise are the subject, but you could just as easily say that the pier stands as the subject as well. The pier works together with the dark sand in the foreground to frame the image, and it also extends into the stronger areas of the image as if it were the subject. Patterns are created with the pier and its reflection. Where the dried up sand washes the pattern away, the sun is positioned to make that point important in the composition. The existence of the pattern on the right side of the frame is balanced by the absence of it on the left side.

Keeping a viewer in the frame

A compositional frame helps keep a viewer from exiting your image and moving on to something else. Imagine that Figure 11-3 included space above the pier for your eyes to wander. This extra space surely would take you away from all that’s happening beneath the pier.

Figure 11-3: The compositional frame in this image also is one of the strongest elements in the composition.

To successfully keep a viewer’s attention through the use of a compositional frame, you need to seal off the edges of your image with elements that exist in the scene in a natural way that doesn’t seem too obvious or forced. Your compositional frame should work in a way that presents the subject and the key elements of your image to a viewer. Most compositional frames are created with elements that are dark in tonality. An image with dark edges and a bright center invites viewers to look at what’s in the center.

The image in Figure 11-4 combines multiple elements to create a compositional frame; the elements work together because they share a dark tone. The dark elements surrounding the subject make the lighter areas seem more inviting, providing a porthole for you to peer into. The dark subject (the bonsai tree) easily stands out against the light background, which immediately draws your eyes in. As you look around the image, the pier and its pilings do their best to keep you from exiting by sealing the perimeter. In fact, the sunlit driftwood occupies the only area along the edge that invites your eyes to leave. This spot stands out and is right at the edge, which can be dangerous compositionally. In this case, though, the driftwood works with the pattern underneath the pier to bring you back into the image. Notice how the sunlight on the piece of wood creates two light areas separated by a dark strip. This pattern looks a lot like the underside of the pier; the similarities cause you to subconsciously compare the two, bringing you back into the scene for another look.

Figure 11-4: Compositional frames are designed to keep your eyes in the image.

Choosing between the Horizontal and Vertical Formats

If you’re using a camera with a square format (or you intend to create an image that will be presented in a circle format or any other shape than the typical rectangle that’s created by most digital SLR cameras), you don’t have to worry about whether your images should be composed vertically or horizontally. However, because most cameras do produce images that have one long side and one shorter side, this decision has to be made more times than not. Digital point-and-shoot and SLR cameras, for instance, use a rectangular sensor that, unless you turn the camera from its natural upright position, is wider than it is tall. Many people forget that they can turn the camera, so they end up with a lot of horizontal images.

Three different elements — the message, the subject, and the environment — can affect which format you choose for your image. I discuss each in the following sections.

Understanding how your message influences which format to use

Your message relies on the format of your image in the same way that it relies on any of the other compositional techniques in this book. Visual changes occur when switching from a horizontal to a vertical format. Sometimes an image works much better as one or the other, and sometimes both formats seem to work equally well.

How is your subject going to fit into your frame? If you have a vertical subject, a vertical frame maximizes how much space that subject can take up in the frame. The same goes for a horizontal subject and a horizontal frame. Because people are vertical when they’re standing or sitting upright, a majority of portraits are taken with the vertical format.

How are the elements in the scene arranged? Your subject may be vertical but the supporting elements are spread out along a horizontal area. You need to determine what’s important to your message and how you can best fit it into your frame.

In Figure 11-5, both formats work well to display the scene, but they both affect the image’s message in different ways. The vertical format in this case allowed me to give more of the frame’s space to the subject than the horizontal format did. That’s because the subject is vertical. Having the woman appear larger in the vertical frame caused the image to convey details about her and the dress she’s modeling, with a moderate emphasis on the environment that surrounds her. Vertical images almost always are used in fashion and portrait photography unless the scene includes multiple subjects. In that case, a horizontal image may be required to fit everyone in.

Notice how the horizontal image in Figure 11-5 has less emphasis on the person and the dress and includes more detail in the environment. The trees to the left of the frame, which don’t show up in the vertical composition, make the image less about the woman and more about the environment. Each composition works well in a different way: The vertical image may work on a magazine cover, in a catalog, or in a look book; the horizontal image is appropriate for a fashion editorial across a two-page spread.

Figure 11-5: Vertical and horizontal image comparison with a human subject.

Figure 11-6 shows two examples of a Miami cityscape image. In most cases, you would shoot a skyline in the horizontal format because of the natural horizontal layout of the scene. In this case, however, the late-evening sun and the city lights illuminate a colorful and cloudy sky. The sky is more interesting than the skyline itself, so the vertical composition is more effective for this scene. The vertical image gives a more complete composition of the light in the sky while providing a good representation of the downtown buildings.

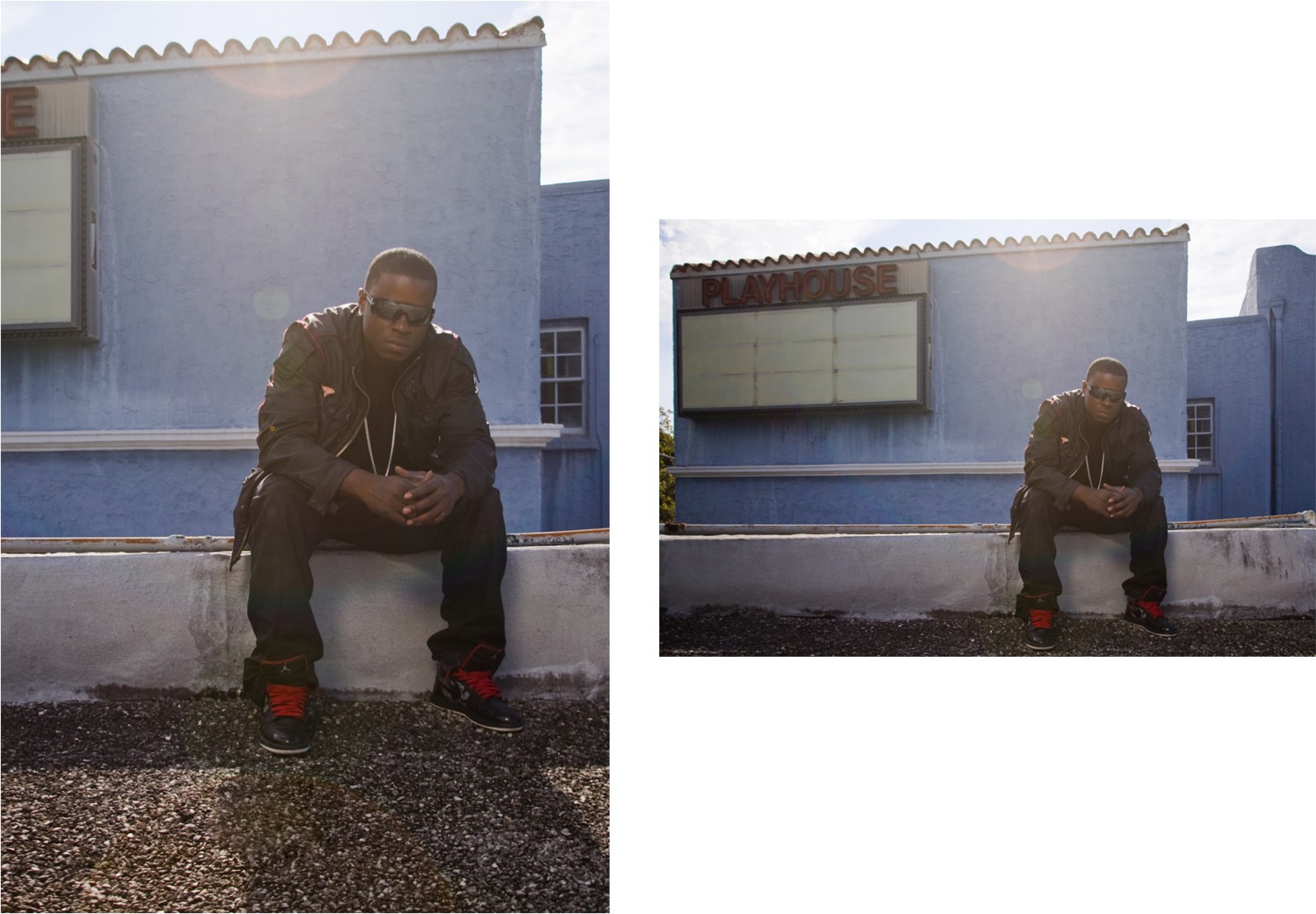

Figure 11-7 shows an example in which the message is completely lost when the format is off. In the vertical version you get a basic idea of the building’s architecture, and you get a small glimpse of the theater-style letter board. However, these details provide an unclear representation of who the man is. The horizontal image, on the other hand, reveals that the man is sitting on a playhouse. You can use this information to assume that he’s an entertainer. The idea behind this image was to use photo-editing software to enter the man’s name into the marquee as if the playhouse were presenting him.

Figure 11-6: Vertical and horizontal image comparison for a cityscape.

I could have changed my perspective in Figure 11-7 in order to create a composition that fit both the subject and the marquee into a vertical frame; however, I wouldn’t have been able to achieve the lighting effect that I got in this image from the new camera angle that would have been required. (For more on perspective, flip to Chapter 8.)

Determining format based on the subject

When the subject itself is the most important aspect of an image’s message, you’ll most likely format the image according to what works best for showing off the subject. As a general rule, a vertical subject works best in a vertical frame, and a horizontal subject works best in a horizontal frame. After all, distributing the space around the subject in a more balanced way is easier when the frame’s orientation is similar to the subject’s. The subject can take up more space in a frame that shares the same orientation.

Figure 11-7: Vertical and horizontal image comparison for an environmental portrait.

If your subject is a winding river, for example, you’ll most likely choose a format based on which way the river runs through your scene. If you’re looking up or down the river, you probably want to shoot vertically to capture the distance that the river stretches. If you’re looking at the river from the side, shoot horizontally to fit as much of it as you can into your composition.

In Figure 11-8, I chose a vertical format because I was shooting a vertical subject. The background isn’t important to the message, so I minimized it. The shapes and lines of the subject fit nicely into a vertical frame; a horizontal frame would have provided only more gray background.

Figure 11-8: The subject dictates the format of this composition.

Letting the environment dictate format

Sometimes the environment surrounding your subject is as important to telling the story as the subject itself. In that case, you include in your frame all the scene’s elements that are relevant to your intended message. If, for example, you’re photographing a doctor who developed a robot that can perform surgery, you may want to choose a format that provides enough space to include her and her creation. The robot would be equally important to telling the story as the doctor.

Figure 11-9 gives an example of an image in which the environment, not the subject, dictates the format of the frame. The full moon acts as the subject in this image. The moon is fairly small in the frame and is neither a vertical nor a horizontal subject, so I could have used a horizontal or vertical format. Instead, the skyscrapers and the lights on the metro rail determined how I formatted this composition.

The horizontal format of Figure 11-9 enabled me to show more of the buildings and to fit the lit area of the metro rail into my frame. I could have achieved great results by shooting this scene vertically, but the subject wouldn’t be affected by the change as much as the environment would be.

Figure 11-9: The environment, not the subject, determined the format of this image.