Turtle Mountain 2204 m easy

Mount Tecumseh 2547 m moderate

Sentry Mountain 2410 m moderate

Crowsnest Mountain 2785 m moderate

Mount Ward 2530 m easy

Window Mountain 2576 m easy

Allison Peak 2645 m difficult

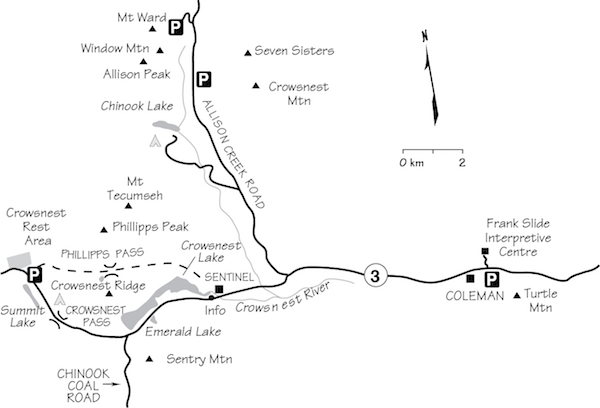

The Crowsnest Pass area of southern Alberta does not lie within any national or provincial park and so is not a busy tourist destination like nearby Waterton. Although lacking a well-developed trail system like a national park, this is no obstacle for scramblers. What the area lacks in trails it makes up for with logging and mining access roads. It is popular with mountain bikers and the ATV crowd, including the use of ATVs even on relatively short approaches. Underbrush is virtually non-existent owing to the dry climate.

Geographically, Crowsnest Pass is situated north of Waterton Park near the eastern edge of the mountains and close to the provincial boundary. The only major road is Highway 3. As one travels west from Pincher Creek, this picturesque route passes through a succession of small towns, including Bellevue, Blairmore and Coleman, then continues to Sparwood in BC and farther. The Crowsnest region is well known for disasters that have occurred in the past. Most noteworthy was the Frank Slide of 1903, when 74 million tonnes of rock avalanched down from Turtle Mountain onto the coal mining town of Frank at its base. The town was buried and some 70 people were killed. Today, an interpretive centre nearby commemorates the disaster. Scramblers can ascend Turtle Mountain for a unique bird’s-eye view of the destruction.

Chinook winds define the climate here, which means a longer, drier season for exploring and climbing. Limestone rock found in the Pass is perhaps a little better quality than in adjacent Waterton Park, but like that area, peaks are comparatively small. Many caves have been discovered here, and spelunking has perhaps been as popular as scrambling in the past. So too are both fly-fishing and mountain biking, and one also finds a disproportionate number of four-wheelers and all-terrain-vehicle lovers. Whatever your pursuit, remember that, as this is not a park, rescue service is not available. In the event of an accident, volunteers and RCMP would have to respond, not park rescue personnel. No system of registration is available here either.

Access The main access road is Highway 3, running west from Lethbridge past Pincher Creek and continuing to Fernie, BC. Forestry Trunk Road 940, a gravel route travelling through the southern part of Kananaskis Country, ends (or starts) at Coleman but is of limited use for access.

Facilities and accommodation Despite what local merchants would prefer, Crowsnest Pass is not a tourist destination like neighbouring Waterton, which in turn is not a tourist destination like Banff. Life goes on much the same throughout the year and the pace tends to be mellow. A few campgrounds service the area, notably at Chinook Lake on Allison Creek Road, while motels, service stations, stores and restaurants are found in the towns. Limited camping and hiking supplies are available in local sporting goods or hardware stores if needed.

Information The tourist information booth is across from the hamlet of Sentinel, 6.6 km east of the BC–Alberta boundary, closed during the winter.

Difficulty: An easy scramble

Round-trip time: 4–8 hours

Height gain: 970 m

Maps: 82 G/9 Blairmore; 82 G/8 Beaver Mines

Turtle Mountain is famously known as the site of the tragic Frank Slide of 1903. Without warning, 74 million tonnes of the mountain collapsed one night, burying the coal mining town of Frank directly below. Some 70 people were killed. This popular trek takes you to the north peak and across the ridge to the higher south summit where the rockslide began and is far more interesting than the limited views from the nearby visitor centre. Turtle and Crowsnest mountains are the “must do” peaks in the region, and thanks to this being the chinook belt, the scrambling season is comparatively long. Try from about early May on.

The trail starts from the southeast corner of Blairmore in Crowsnest Pass. Drive into the east entrance to the town and turn left at 133rd Street. At 15th Avenue, turn left again, go one block and follow a gravel road uphill to park in a clearing under powerlines close to the peak. The trail begins down the hill at the low point near the north end of the mountain.

Walk downhill under the power lines and notice a good trail which angles diagonally rightward toward rock cliffs at the north end of Turtle Mountain. Painted rock markers immediately show the correct route, which has been improved over the years and is well travelled by locals. It angles through coniferous forest and up the hillside to gain the main spine of the mountain. Short stretches of slab create brief diversions as you go. Much of the route travels along the open crest, offering a fine view of Crowsnest Mountain behind you and green prairies to the east. This area is notorious for strong winds and you will notice both the sturdy, stunted nature of any trees surviving here and the lack of branches on the windward side. When these winds are cranked up, ski poles are invaluable for the treacherous gusts which buffet these open slopes.

Both the outing and the scenery get more interesting once you reach the north peak. Ahead lies a hodgepodge of fissures, boulders and debris caused by the massive slide that sundered the peak and cascaded down onto the town of Frank. Descend slightly and follow various trails to the low point and across, dodging great stress fractures and boulders. Resist the urge to stand too close to peer down the face, as much of it is still unstable and overhanging. In 1997 one particularly large sloping block near the edge made a picturesque, airy photo spot but it has since shifted forward, making it much trickier to attain due to a widening gap around it. Early-season scramblers should note that crossing this section while it is snow-covered requires care and could lead to an unexpected fall into a deep fissure. This would result in serious injuries, not unlike crossing a crevassed glacier. Once you’re across, tramp up a hillside festooned with sensors placed by the Geological Survey of Canada which monitor movements of the mountain. The south peak, which in 2013 had a webcam, is considered to be more prone to failure, and the majority of the 40 solar-powered tracking sensors are located here. Knowing this, you probably won’t want to spend an eternity on top, even if it is sunny.

From the south summit you can see the incredible horizontal distance the slide debris travelled. The farthest reaches of rock are more than 2.5 km from the edge of the face and one wonders how boulders could possibly tumble so far, especially considering their size. One theory supposes that smaller particles settle to the bottom and act as ball bearings allowing larger boulders to travel farther horizontally. Until a similar event can be recreated and filmed, however, this supposition still may not be the complete or correct explanation.

The original shape of this mountain was a geological structure called an anticline, or an upside-down U, a shape which creates tension forces on outer layers of the curve where the strata bend downward. This particular shape, along with water seeping between layers and freeze–thaw cycles probably helped loosen and lubricate the strata, releasing the deadly avalanche of rock debris seen today. Coal mining within was not to blame as was once thought. Prior to this event the mountain was rounded like a turtle’s back and the name made perfect sense.

Summit views range from the more southerly peaks located in the Waterton Park and Castle Wilderness areas, to larger mountains to the west in BC, to an eastern horizon of prairie. Previous editions of this book suggested the possibility of traversing the mountain and doing a loop, but because this would mean crossing private land it is suggested you return the same way, which is what most everybody did anyway.

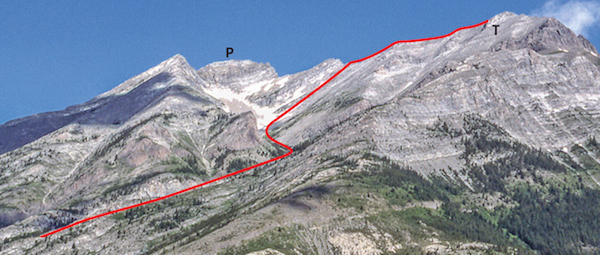

Turtle Mountain from the visitor centre. Ascent route follows skyline ridge from right to left.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling on scree and slabs via south slopes

Round-trip time: 5–9 hours; 3–6 hours from Phillipps Pass

Height gain: 1175 m in total; 975 m from Phillipps Pass

Map: 82 G/10 Crowsnest

Mount Tecumseh offers little in the way of difficulty or exposure and is a pleasant outing in the Crowsnest Pass area. Expect minimal exposure but a lot of scree on this small peak. A bike saves time, especially on return. Try from June on.

The ascent begins from Phillipps Pass, situated 2 km north of and running parallel to Crowsnest Pass, which separates Mount Tecumseh from Crowsnest Ridge. Crowsnest Ridge is crowned by a highly visible microwave tower. Phillipps Pass can only be reached via the power line from the west side. The east side approach can no longer be used, as it crosses private property and you could be charged with trespassing.

Drive to the Crowsnest rest area, 2 km west of the BC–Alberta boundary on Highway 3. The power line right-of-way is a short distance uphill through the trees and provides access. Either hike or bike 4.2 km, which will place you 700 m east of a fenced-in, metal-clad building at 698017 near a steel power line support tower. The mouth of the ascent drainage emerges here. Walk upstream along the often dry streambed draining the south side of Mount Tecumseh. There isn’t really a trail but travel is easy. The abrasive action of water over time has carved solid limestone into a delightful series of “sinks” joined by twisting, smooth-walled channels that are fun to try to ascend directly. You can also trudge along either side if you are not this easily amused.

Within an hour the streambed disappears and you reach a landscape of immense boulders, apparently debris from steep slabs up to the right. Shortly beyond these crumbling rocks, turn sharply left past a stand of evergreens and into a scree basin between steep walls of Phillipps Peak and Mount Tecumseh. Although you may have been tempted to continue directly ahead for the top rather than turn left into this basin, cliff bands of downsloping rock complicate more direct lines to the summit. The suggested route allows you to sneak up from the southwest on scree and talus.

From the basin, either tramp straight up or angle slightly to the right as you go. The objective is to gain the ridge above, which leads easily to the summit just east. Contrary to expectations, the crest of the ridge is mostly a plod with no exposure. A metal survey pole crowns the top.

From the top, the most notable features of the landscape are lonely Crowsnest Mountain and Seven Sisters sitting well apart from the Highrock Range. At one time they were one section of a massively thick and continuous sheet of limestone, pushed hundreds of kilometres in from the west that rode up over existing younger rocks beneath. Geologists call this north–south demarcation line the Lewis Thrust. Owing to the erosion of Allison Creek, Crowsnest Mountain, a visible reminder of this cataclysmic upheaval, has become a klippe – an outlier isolated from the main range.

You may wonder why the high point two pinnacles to the west deserves a separate name. “Phillipps Peak” and “Tecumseh” were both in use until the latter name was officially adopted. The runner-up title was bestowed upon a lower point to the west. You can ascend Phillipps Peak starting farther west along Phillipps Pass and circle left to gain the west ridge. Expect a short section of difficult scrambling on the ridge before the highest point.

There are various explanations for the name of this peak and pass. Michael Phillipps of Elko, BC, was the first white person to make use of the pass, apparently while scouting out trapping territory in 1873. Bison had used it for centuries but Indians had for some reason avoided it. The mining ghost town of Michel lies just a few kilometres west. Tecumseh, a Shawnee war chief, rallied other Indian tribes into an allied force to combat an American territorial expansion. His forces joined with those of the British and Canadians in 1812, a crucial time during the conflict. In a tragic twist of fate, Tecumseh died fighting his own people.

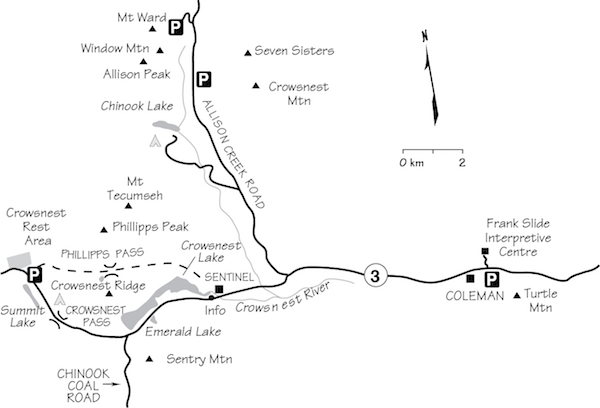

Mount Tecumseh and Phillipps Peak. Route starts from Phillipps Pass. P: Phillipps Peak; T: Tecumseh.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling via west ridge; minimal exposure

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 1025 m

Map: 82 G/10 Crowsnest

Diminutive Sentry Mountain guards the gusty gap of Crowsnest Pass, where blustery west winds whip the waters of Crowsnest Lake into a maelstrom of whitecaps. This ascent is largely a non-technical ridgewalk that becomes more interesting near the top. Good views throughout.

You can approach the west ridge of this peak directly from almost anywhere along the first couple of kilometres of Chinook Coal Road. Since the initial and perhaps only real challenge is to cross the creek, you should take the time to scout out the best crossing point along this stretch. Late-summer flows are typically only calf-deep but rocks are slimy.

Drive to Chinook Coal Road, 3.7 km east of the BC–Alberta boundary and 4.8 km west of the tourist information booth on Highway 3 in Crowsnest Pass. Depending on road conditions, drive south about 1.7 km or as far as you dare, to access Sentry Mountain’s west ridge. As of 2014 the road was very rough after 800 m.

Cross the stream and tramp to the top of the limestone quarry. The terrain above this point is easy going through open forest as you hike steadily upwards; occasionally a game trail materializes to coax you along, only to disappear at the first open clearing. The ridge is broad for the first few hundred metres of elevation gain but becomes more clearly defined higher up. Scattered whitebark pine are interspersed with bleached, twisted trunks stretching dry limbs skyward – a stark reminder of the enduring effects of a past forest fire. Underfoot, the stony landscape is graced by patches of kinnikinnick, or bearberry. Kinnikinnick is an Indian word that roughly translates to “smokable,” and rough it is, too. No wonder gifts of tobacco were popular.

Enjoy the fine view to the south and west as you draw nearer to a “bumpy” portion of the ridge. This part gets a little more interesting, and there are about 275 vertical metres left to go now. Each hump seems to rise a little more steeply, suggesting a drop-off on the other side. Erosion has been thorough, though, and you can continue along quite nicely. One brief notch entails a minor detour to the left on scree and ledges, but not until close to the top does a more serious-looking obstacle rear up. The entire ridge appears protected by a slabby, triangular rock face seemingly straddling the route. Tackling it directly is a challenge many won’t bother with, despite good solid rock. Alternatively, either side will suffice to dodge around it. A detour to the right necessitates a short scramble down to scree, followed by a plod back up and around this stony outcrop. The left side detour may be a better choice. It involves no elevation loss, and with a bit of imagination you may even see a path.

With this 20 or 30 m behind you, the true summit is close. The ridge crest narrows dramatically in a couple of places, but except for one point where you must descend a 2 m step, you can avoid most airy bits entirely on scree along the right (south) side. If exposure doesn’t bother you, the most sporting route follows right on the crest.

The summit is spacious enough to relax without fear of rolling off in your sleep. You’ll notice you could probably wander south along the ridge for quite a distance before encountering any problems, though this would first necessitate about 200 m of elevation loss. Conversely, it is easier to sit on your gluteus maximus, stare at big peaks to the west and debate which one is 3359 m Mount Harrison, the last Rockies peak over 3353 m (11,000 ft.) to be climbed. About 1963, cartographers researching new data “found” it, although nobody else knew it had gone missing.

The photo suggests many promising routes up Sentry Mountain and this is by no means the one and only. Other routes may involve more loose rubble than this particular option does. Some years, the roadside quarry does not operate, so you could approach the west ridge by driving right into the quarry and hike to the ridge from there. This would eliminate the creek crossing, but the heaps of rock debris are not a particularly aesthetic start to the trip.

The west ridge ascent on Sentry Mountain. Many other route possibilities exist.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling via the north side

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 1100 m

Map: 82 G/15 Crowsnest

“Like the sacred Fuji Yama of Japan, Crow’s Nest mountain rises abruptly out of the earth, with no other mountains within miles,” wrote P.D. McTavish. He was recounting the second recorded ascent of the peak, in 1905. His relatively inexperienced party took a circuitous route and it seems they encountered serious climbing. By comparison, the “tourist route” used today is much easier and incidentally was first ascended in 1915 as a solo trip. It is an eye-catching little peak and worth the time if you’re in the area. Try from June on.

Drive to Allison Creek Road in Crowsnest Pass, 9.6 km east of the Alberta–BC boundary and 14 km west of the Frank Slide Interpretive Centre on Highway 3. Follow this road for 9.7 km and park on the shoulder. The approach trail begins directly opposite this wide spot.

Follow the hiking trail into the forest, where it soon meets an ATV-width trail heading for Crowsnest Mountain. Pine forest gives way to scree slopes at the north end of the peak where multi-pinnacled Seven Sisters Mountain joins Crowsnest Mountain. There may be flagging, but if it isn’t visible, ascend scree to the right of the black waterfall marks at the first band of cliffs. Climb through the lower rock steps, then traverse left on a scree ledge below the black, wet walls of the second cliff. More than one trail can be found below the traverse ledge but they should all rejoin at that spot.

To overcome the second cliff band you must scramble up a long gully to the left. Toward the top of this gully move left and avoid the damper, dirtier right branch. A long piece of chain anchored here aids the ascent, and most scramblers are happy to use it going both directions, even when conditions are dry. Above this gully the way is evident, and you should have no problems as you zigzag up gentle scree to the top.

Gould Dome and more prominent Tornado Mountain dominate the view to the north; Mount Ptolemy is the highest point in the cluster of summits lying nearby to the south.

Two theories confuse the origins of the Crowsnest name. One concerns a slaughter of Crow Indians by Blackfoot Indians near the town of Frank, where they were corralled, or in a “nest.” According to Reverend John McDougall, though, “On this trail through the mountains there was a nest which was occupied annually by crows,” and this explanation is more in favour.

Descend by the same route.

Crowsnest Mountain showing route of ascent. L : lower rock steps; T: traverse; G: gully.

Difficulty: Easy scramble

Round-trip time: 2.5–5 hours

Height gain: 625 m

Maps: 82 G/15 Tornado Mountain; 82 G/10 Crowsnest

Despite the simplicity of the ascent and its proximity to locally popular Window Mountain Lake, Mount Ward has largely been overlooked in favour of locally famous Crowsnest Mountain nearby. Still, the view from the top is worthwhile and allows a close look at the scramble route up to the huge opening in nearby Window Mountain, another Crowsnest area landmark. This is a comparatively short trip that can be extended to a full day to include more difficult scrambling along connecting ridges south to Allison Peak. Try from June on.

From Highway 3, turn north onto Allison Creek Road, 9.6 km east of the Alberta–BC boundary and 14 km west of Frank Slide Interpretive Centre. Follow the road for 16.8 km and turn left onto Window Mountain Lake Road (not signed). The last few kilometres of Allison Creek Road may sometimes be unpleasantly rough. So too is the 1.3 km drive along Window Mountain Lake Road, which ends at a small parking area and trail sign.

The sign says it is 4 km to the lake. Initially you follow an old logging road toward and into forest, heading for a treed hump. After angling up over this hump, the route descends slightly and you pass to the right of a small marsh, reaching Window Mountain Lake in about 20 minutes. The lake is a pretty place, sheltered by Mount Ward to the south and a high, open ridge to the west. This ridge is not Mount Ward, but if desired its north end can be reached by angling north up open slopes.

Scramblers bound for Mount Ward should hike around the right-hand shore to the far end, where an obvious slope leads up into a small valley and easy west slopes of the peak. Occasionally, animal trails are encountered in the moss and scree higher up but are not needed. Glancing back, you will notice that the open ridge just west of the lake would make a possible variation for the return.

From Mount Ward several other easy ascents nearby are apparent, including an unnamed peak immediately north of Racehorse Pass and an 8100 ft. (2470 m) point 1.5 km northwest of the lake. The road to Racehorse Pass begins 1.6 km north of Window Mountain Lake turnoff and was open at the time of writing in 2014.

After you have studied Crowsnest Mountain, patchwork clear-cuts to the north and the distant peaks to the west, either return the same way or continue south to Allison Peak (2645 m).

The intriguing opening on nearby Window Mountain (702130 on 82 G/10) lying immediately south is apparent. The route to the window is the rubbly chute directly beneath it, readily reached from clear-cuts to the east via an ATV trail 700 m south of the Window Mountain Lake turnoff. Furthermore, from the low point in Mount Ward’s southwest ridge, it MAY be possible to angle diagonally down to the rocky valley to reach the bottom of the scree gully leading to the Window. If so, rather than return the same way, descend east to logged areas and circle back around the east side of Mount Ward to your vehicle.

The safest way to the top of Window Mountain is via scree slopes and westward-sloping ledges starting above the two large snow patches visible in the picture on p. 68.

According to Holmgren and Holmgren’s Over 2000 Place Names of Alberta, Captain A.E. Ward was secretary of the British Boundary Commission, Lake of the Woods to the Rockies, in 1917.

Difficulty: Difficult, exposed and loose

Round-trip time: 3–5 hours from Mount Ward

Height gain: about 250 m

Height loss: about 250 m

Climbers and experienced, capable scramblers can continue south along the connecting ridge to reach Allison Peak. The traverse involves occasional detours to either side of the ridge as necessary. Some parties find the bit from Mount Ward to the intersection of Window Mountain more challenging than the section of ridge that continues south to Allison Peak. Avoid this traverse unless it is free of snow. A few minutes before reaching the top of Allison Peak you might find the 1 m × 2 m window through this ridge, close to the crest. Return all the long way back to Mount Ward and Window Mountain Lake.

Although attempting the summit of Window Mountain via the connecting ridge may look feasible, descending to the low point is dangerous owing to large, loose blocks of rock and steep, rubble-covered slabs. The terrain is very exposed and cannot be recommended.

Douglas Allison, a one-time member of the Royal North-West Mounted Police, lived near the creek now bearing his name.

Route up to Window Mountain’s window.

Window Mountain from the road. Mount Ward would be to the right; Allison Peak is far to the left.