Mount Fullerton 2728 m moderate

Mount Remus 2688 m moderate

Mount Romulus 2832 m moderate

Mount Glasgow 2935 m moderate

Banded Peak 2934 m easy

Cougar Mountain 2863 m moderate

Nihahi Ridge Traverse 2530 m moderate

Compression Ridge 2500 m difficult

The Wedge 2665 m difficult

Opal Ridge 2575 m moderate

Mount Kidd South Peak 2895 m easy

Mount Kidd 2958 m moderate

Fisher Peak 3053 m difficult

Mount Bogart 3144 m moderate

Mount Lawson 2795 m moderate

Mount Denny 3000 m moderate

Mount Potts 3000 m difficult

Grizzly Peak 2500 m easy

Mount Evan-Thomas 3097 m difficult

Gap Mountain 2675 m moderate

Tombstone South 3000 m moderate

Mount Hood 2903 m moderate

Peaks in this chapter are found in two specific regions in the Front Ranges of the Rockies: Little Elbow Recreation Area and Kananaskis Valley. Because they are close to Calgary, both are extremely popular with city dwellers, especially on weekends.

The two locales are more or less adjacent, with topography similar to other places in the Front Ranges: long limestone ridges, strata dipping to the southwest. In the Opal Range, strata are tilted upward to nearly vertical. Snowfall is comparatively light, as is rainfall, making for a long scrambling season. Kananaskis Valley is unique in that its alignment is northeast to southwest, and for reasons that I don’t completely recall, this alignment tends to make valleys slightly warmer. It may be that this orientation allows the mountains to funnel warmer west or southwest winds (such as chinooks) along the corridor’s length rather than act as a windbreak. In any case, the phenomenon makes for good scrambling but poor skiing. Like the Canmore Corridor, these areas offer fine early season objectives.

So far, there has not been the enormous amount of development in Kananaskis Valley that was once proposed. Planned alpine villages have not materialized and hopefully never will. Opinion polls have consistently shown that the public does not want increased development in Kananaskis, but that is no guarantee that the valley is safe from developers. With the population ageing, Kananaskis Country may well increase the size of existing campgrounds to accommodate more RVs and trailers but there are no plans for bingo halls just yet.

Access The Little Elbow Recreation Area is reached from the village of Bragg Creek, 40 minutes southwest of Calgary. Elbow Falls Trail (Highway 66) leads west to the recreation area. This road is closed at Elbow Falls from December until mid-May. The area features several hiking, biking and horse trails and a large campground. Roads and trails here suffered heavy damage in the 2013 flooding, with entire bridges washed away. Repairs will be ongoing for some time. Kananaskis Valley is reached via Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40) from the Trans-Canada Highway, 65 km west of Calgary. This road continues south, crosses Highwood Pass and travels east through the foothills past Longview to meet Highway 2 eventually.

Facilities Canmore has the best array of facilities and services and is the major tourist hub of the area. Just east of the Highway 40 and Trans-Canada junction is the Chief Chiniki gas bar, and a store across the road has a limited selection of food and snacks. Stoney Nakoda Resort and Casino (888-862-5632), right at the Trans-Canada and Highway 40 junction, has cafes, rooms, helicopter rides and more. It bills itself as “Base camp for the Rockies.” The jury is still out on that. The town of Bragg Creek, east of Little Elbow Recreation Area, has an ever-expanding number of shops, restaurants, stores and services too. In Kananaskis Valley, limited groceries are available at Kananaskis Village Centre near the Nakiska ski hill. What is left is largely hotels and bars. Mount Kidd RV Park (403-591-7700) just south has a small store. Farther south, gas and a modest selection of food and supplies can be found at Fortress Junction (403-591-7371). Boulton Creek Trading Post (403-591-7678) near Kananaskis Lakes has a cafe and store. Boundary Ranch on Highway 40 has a steakhouse that is open during July and August (403-591-7171). Note that many of these establishments roll up the carpet after Labour Day weekend in early September when crowds magically diminish.

Accommodation Canmore offers the most complete range of accommodation. Hotels and Ribbon Creek hostel are at Kananaskis Village, and while K Country has many campgrounds, expect most to fill by early afternoon, especially on Fridays. Mount Kidd RV Park in Kananaskis Valley is the most decadent campground to be found; showers are available, too. A large campground can be found at Little Elbow Recreation Area. For affordable accommodation in the company of fellow climbers and hikers, check out the Alpine Club of Canada clubhouse. It is 2 km northeast of Canmore on Bow Valley Trail, at the foot of Grotto Mountain.

Information In Kananaskis Valley, information is available at Barrier Lake and at the visitor centre in Peter Lougheed Park. Other information centres are at Elbow Valley on Elbow Falls Trail and at Bow Valley Provincial Park near Seebe on Highway 1X.

Barrier Lake Info Centre 403-673-0760

Peter Lougheed Provincial Park Info Centre 403-591-6322

Elbow Valley Info Centre 403-949-4261

Kananaskis Village Centre 403-591-7555

Backcountry camping permits 403-678-3136

Updated trail info: kananaskisblog.com.

Emergency Park rangers are based at Elbow ranger station and Boundary ranger station by Ribbon Creek, which also serves as the emergency services centre. RCMP are in Canmore and at the Ribbon Creek emergency centre.

Difficulty: A moderate scramble via northeast slopes and ridge. Good routefinding required on more challenging southeast ridge.

Round-trip time: 6–11 hours

Height gain: 1050 m

Maps: 82 J/15 Bragg Creek; Gem Trek Bragg Creek–Sheep Valley

Mount Fullerton is one of the Front Range peaks that comes into condition comparatively early in the season, making it a good May starter. Depending on whether or not you enjoy testing your routefinding skills, there is a choice of routes that can be combined into the traverse. A bike is a time-saver on the approach.

Park at Little Elbow Recreation Area west of Bragg Creek on Highway 66. Unless you are a registered camper, the parking area is to the left of the campground entrance.

Walk or cycle west through Elbow campground to Little Elbow trailhead. Little Elbow trail was once a driveable road and is well suited to mountain bikes for the 3.5 km to Nihahi Creek. Allow 40 minutes on foot to reach this point. At Nihahi Creek a signed trail to the right leads you into a broad alluvial streambed – typically bone dry – running north between Nihahi Ridge on the right and Mount Fullerton on the left.

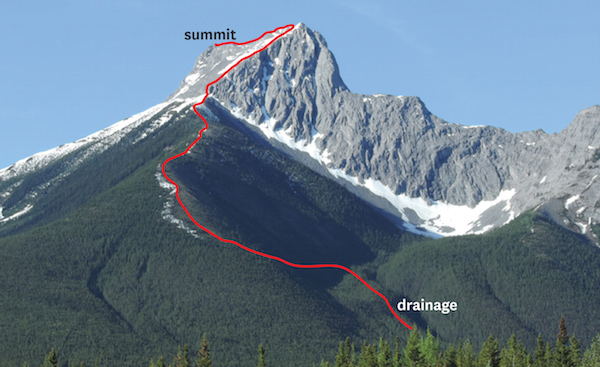

About 1–1.5 hours from Little Elbow trail, the main branch of the valley turns abruptly westward and circles around to the north side of the objective. At this point you can either follow the small, rocky drainage that emanates from an amphitheatre at 445320 on the northeast side of Mount Fullerton and gain open slopes on the right, or you can cut directly through trees to this open northeast ridge. The way up then becomes obvious. Only near the top at a few short rock steps is this route a hike, and before you know it you’re on the summit. A lower, unnamed point to the west is a 20-minute walk away.

If you choose to ascend by the more challenging southeast ridge, this northeast ridge route makes for a no-nonsense descent. The stony plod back along Nihahi Creek can hardly be called inspiring, though.

The long southeast ridge is a much more challenging undertaking. You can gain it at Little Elbow trail just west of Nihahi Creek, or, to avoid the first two hours of forest, continue partway up Nihahi Creek. Ascend open slopes and dry drainages at any of several places on the east side of Fullerton to gain the southeast ridge. Continue north, passing two lesser but well cairned summits along the way to where the real routefinding begins.

Contrary to more typical Front Range topography where strata are bedded with a noticeable dip to the west or southwest, the rock layers here dip to the east. This geological anomaly presents a challenge. Collin Smith pointed out this route, which is fairly straightforward and better than my previous description. From the second high point where it drops off, descend on the north (right) side, scrambling down past four rock bands. From the correct ledge, you should see up ahead a free-standing rock pinnacle against the skyline on this same ledge system. The route goes left of this pinnacle and continues to the next high point. From that high point, switch over to the left-hand (south) side for the rest of the way to the summit. Snow lingers on the shaded north side here and adds to the difficulty, so save this route until June at the earliest. Descend via the easier northeast ridge and gully.

C.P. Fullerton, for whom the mountain was named, was once chair of Canadian National Railways.

Southeast Ridge as seen from summit. From the second high point, the easiest route descends several rock bands as shown and goes behind a pinnacle farther on. Beyond the red arrow, the route switches over to the left (south) side for the remainder. PHOTO: COLLIN SMITH

Looking west to Mount Fullerton from along Nihahi Ridge. N: NE ridge; S: SE ridge.

Difficulty: Difficult via chimney, moderate/difficult by north slope

Round-trip time: 6–8 hours if approaching by bike

Height gain: 1070 m

Maps: 82 J/15 Bragg Creek; Gem Trek Bragg Creek & Sheep Valley

Mount Remus, pint-sized brother to adjacent Mount Romulus, is a logical trip for shorter days of autumn when the Little Elbow River is low enough to wade. A bike for the approach, old runners to wade the river and ski poles for the scree are all useful for this ascent. This mountain has been largely overlooked in the past but is a pleasant change from more often visited destinations Most parties find the ascent quite enjoyable.

Park at Little Elbow Recreation Area west of Bragg Creek on Highway 66. Parking is to the left before the campground entrance.

From the gate at the west end of the campground, follow Little Elbow trail for 6.6 km (some 45 minutes by bike) to a wide flat spot on the shoulder. This once driveable road is perfect for mountain bikes, but watch for hikers and horse riders too. If you meet horses you should get off your bike until they pass. At 6.6 km you will be directly across from an obvious wide scree gully leading up to the skyline ridge of Mount Remus. From late August on, the Little Elbow is typically calf deep and is an easy, if chilly, ford.

After sloshing across, head briefly through trees to the drainage gully and gain a good trail on the right-hand side above the drainage. Mount Glasgow rises behind you. Higher up, the gully diverges into two or three drainages before the ridge. Either branch to the left will do. The preferred descent gully comes down on your right and is identifiable by all the brown shale. Continue past it. The waterworn bedrock in the gullies degrades to loose talus for the last section.

Amble west along the ridge to the summit block, where the only challenge awaits. You have two choices here. Many parties climb the facing cliff band by a chimney where the cliff is least high. This is the quickest way. Slog up scree to its narrow mouth. It is steep but there are fairly decent holds for climbing the chimney, especially on the wall to the left. The total chimney height is about 5–7 m, but some may find it unnerving without a rope – and harder when wet. Depending on the time of year, it may be choked with snow, in which case parties have climbed a crack a few metres farther left instead. Once you’re up, a short walk leads to a large cairn on the broad summit plateau.

If the north side is dry you can contour around to that side and scramble up fairly steep rock steps overlain with rubble. A rock band must be overcome initially and reports suggest that it is not necessarily that much easier than the normal chimney route. It is longer and you must also lose a bit of elevation initially if you choose the north side.

To the west the most recognizable peak is Mount Blane, sporting a tall, knife-shaped feature on the south ridge called “The Blade.” Glasgow, Cornwall and Banded Peak lie straight south of you.

Return the same way, or better yet, traverse farther east along the ridge toward a minor summit. Then you can angle directly down massive slopes of brown shale below for a quick descent back to the main ascent gully.

Romulus and Remus were twin brothers and the founders of ancient Rome. Mount Romulus rises straight west of Mount Remus and displays an impressive escarpment. Beginning farther upvalley, it too is a scramble.

Mount Remus showing ascent route and D: optional descent.

Mount Remus. The usual ascent route follows an obvious crack to left at the summit cliff band.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling; mostly a hike

Round-trip time: 5–7 hours from campsite to summit; 1 hour to campsite by bike

Height gain: 1230 m

Maps: 82 J/15 Bragg Creek; 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Bragg Creek & Sheep Valley

If you have a mountain bike for the 11-km approach, Mount Romulus is a pleasant way to wind down the scrambling season. You are unlikely to find a beaten path or crowd on this peak. Between the long approach and the river crossing, you may have it all to yourself, despite a nearby campsite. A bridge and part of a trail washed out here in 2013 and repairs were ongoing in 2015. Try from mid-June on.

Park at Little Elbow Recreation Area, west of Bragg Creek on Highway 66. Parking is to the left before the campground entrance.

From the gate at the west end of the campground, follow Little Elbow trail for 10.8 km to Romulus backcountry campsite. This once driveable road is perfect for mountain bikes (watch for hikers and horse riders), and most parties will cycle if given the choice. If you meet horse riders you should get off your bike until they pass.

Enter Romulus campsite and ride to the back of it to wade the river. An old pair of runners or shoes is handy for the crossing, best done later in summer. Once the feeling returns to your feet, head into the trees and up the hillside along the base of Mount Romulus. The idea is to get into a large drainage coming off the south end of the peak at 408253 and later gain the south ridge. If you’re lucky you may stumble across a good hiking trail that wanders along through the forest into the north fork of the Elbow River. Whether you find the trail or not, head west along the foot of the peak. Angle up into the big drainage on the south side just before the river emerges from a canyon.

Follow the drainage up into a big scree basin. The ridge above on the left leads to the summit, which lies some distance east, and there are a few places to get on it. Either one of two gullies on the left close to or beyond the last little trees offers a way through rock bands and onto the ridge. Otherwise, you can also continue straight ahead up loose brown scree toward a col and reach the ridge from there. This involves a lot more traversing hillside on rubble.

You cannot get lost once you’re on the ridge. It is not narrow and is mostly a walk but it has an annoying habit of going down instead of up. The last such dip before the summit is where Bill Kerr’s shortcut approach (moderate scrambling) meets with this south ridge. Leave Little Elbow Trail at about the 8-km point and ascend the obvious drainage directly across the river toward Romulus’s summit cliff band. At the cliff band, a hidden ramp leads up to the right and deposits you on the south ridge – or at least provides a route for you to tramp up under your own steam. The summit gives a close view of Romulus’s counterpart, Mount Remus, and the vertical walls guarding it. Distant peaks like Mount Rae can also be seen. Like many ascents in the Front Ranges, however, the absence of glaciers and craggy summits renders the landscape a bit drab, with muted shades of grey, brown and dark green predominating. Once the landscape becomes a little too melancholy, return the same way.

View of scree basin and south ridge of Mount Romulus. D: drainage; B: basin; S: summit.

Mount Romulus shortcut approach.

Difficulty: Moderate scramble via snow/scree slopes and west ridge

Round-trip time: 7–12 hours

Height gain: 1310 m

Maps: 82 J/15 Bragg Creek; Gem Trek Bragg Creek–Sheep Valley

An ascent of Mount Glasgow offers a close look at a notable tetrad of Front Range peaks that includes nearby Mount Cornwall, an unofficially named summit called Outlaw Peak and, lastly, Banded Peak at the southeast end. The most identifiable feature of the group may be the east aspect of Mount Cornwall. This scree slope holds snow like moss holds moisture. By midsummer it usually displays about the only snow on the horizon. Two summits to the south, Banded Peak’s triangular shape, accentuated by a conspicuous horizontal band just below the top, further contributes to the group’s unique appearance. With mountain bikes and proper logistical planning, the general cluster can be conquered in a long day. Try from mid-June on.

Drive to Little Elbow Recreation Area west of Bragg Creek on Highway 66. Unless you are a registered camper, parking is to the left of the campground entrance.

Walking the initial 1.5–2 hours is drudgery, so I suggest you cycle it. Almost everyone else will probably be biking along this old road too. From the parking area follow the road through Little Elbow campground past the gate and continue along Little Elbow trail. Once you cross the river to the south side on the blue bridge, watch for the first drainage that crosses the trail at 443271, 7.2 km from the gate. This is a seasonal stream and may not even be flowing, so watch carefully (cairn if you’re lucky!). Emanating from a stony valley between Glasgow and an 8900 ft. (2700 m) outlier (460258) to the north, the drainage gives access to easy west-facing slopes leading to Glasgow’s barren summit.

Hike along the left side of the drainage, keeping above it for the first part where it becomes a narrow canyon. Once this chasm peters out you can boulder-hop straight up the creekbed. At the far (southeast) end of the valley, turn right and outflank steep walls via a long scree slope (snow-covered during June and later). This takes you around onto the rubbly west ridge and the summit. There are no difficulties, but this route is a strong argument for using ski poles on scree. With an ice axe, you can glissade any snowy bits on return.

Ambitious folks will note the possibility of extending the trek south to Mount Cornwall, then southeast to Outlaw Peak (455205), and finally over to Banded Peak. Only the descent of the ridge from Glasgow toward Cornwall presents any challenge. You can then hike out down the east fork of a southeast-trending drainage (462195) between Banded and Outlaw peaks to reach Big Elbow trail at 478178. You intercept this trail at the second drainage past (southwest of) the bridge that crosses over to the north side of the Elbow River (15.2 km from the trailhead). To do this rambling traverse, parties have approached opposite ends of the circuit on mountain bikes, then swapped for the return pedal back to Little Elbow Recreation Area. Naturally, the long daylight of June and July is preferred for this lengthy undertaking.

Bob Spirko’s group ascended Mount Glasgow more directly by heading through forest to gain the east ridge of the peak (visible from parking lot). It is reportedly a more interesting and challenging route that does not require a bike for approach.

Glasgow and Cornwall were cruisers that played a prominent role in the 1914 Battle of the Falkland Islands.

The Mount Glasgow ascent route, seen here from Mount Remus, mostly involves reams of rubble.

Difficulty: An easy scramble via southwest scree slopes

Round-trip time: Allow a full day even with a bike approach

Height gain: 1310 m

Maps: 82 J/10 Mount Rae; Gem Trek Bragg Creek–Sheep Valley

For folks who aren’t interested in the entire Glasgow to Banded traverse, Banded Peak alone is a worthwhile outing. As you drive west toward the Rockies, this summit is recognizable by its pyramidal shape accentuated by a horizontal rock band near the pointy top. Much of the approach uses an old road and without a bike it is not logical as a day trip. Try from about mid-June on.

Drive to Little Elbow Recreation Area, west of Bragg Creek on Highway 66. Unless you are a registered camper, parking is to the left of the campground entrance.

From the parking area follow the road through the campground and branch left onto Big Elbow trail, immediately crossing the bridge over Little Elbow River. Cycle along this road (watch for horses and hikers) for 15.2 km from Little Elbow bridge, at which point you should be close to the drainage at 478178. The road rises slightly up a small hill here; the correct drainage is immediately past this rise. This drainage emanates from the south side of Banded Peak and provides access to the easy southwest slopes.

Stash your bike and head up along the right side of the creek. Later in the summer this will be dry. Look for an animal trail on the hillside above the creek to avoid bushes in the drainage. The streambed soon opens up and you will have little problem reaching the basin below the peak at 463193. Just be sure to follow the right-hand fork. The basin is open and you can easily tramp up to the top of Banded Peak on your right or Outlaw Peak rising straight ahead. The summit has a view of prairies to the east and larger peaks to the south and west, most notably Mount Rae (3218 m). Vast amounts of rubble comprise this part of the Rockies. If the rest of the province ever runs out of scree, this area will be worth a mint. Unless you are traversing to mounts Cornwall or Glasgow, return the same way.

Banded Peak route from Cougar Mountain.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling and much scree via northeast ridge

Round-trip time: 7–11 hours

Height gain: 1250 m

Maps: 82 J/15 Bragg Creek; Gem Trek Bragg Creek–Sheep Valley

Cougar Mountain sees few visitors, but because of its location in the drier Front Ranges, you can ascend it when bigger peaks are snowbound. As with other summits in the Little Elbow Recreation Area, a bicycle is the sensible option for the 12-km approach. The ascent is straightforward and offers a fine view of the steep east faces of Mist Mountain and Mount Rae, big peaks like Mount Assiniboine and peaceful, rolling prairies to the east. Try from mid-June on.

Drive to Little Elbow Provincial Recreation Area, west of Bragg Creek on Highway 66. There is limited trailhead parking by the bridge over the Little Elbow River in the campground. Otherwise, unless you are a registered camper, parking is to the left of the campground entrance.

Cross the suspension bridge over the Little Elbow and cycle the old road for about 12.3 km. This is a multi-use trail, so please be cautious and courteous. When meeting horseback riders you should get off your bike, move to the side and let them pass you. As you ride along the road toward the objective there are good views of Cougar Mountain from several points. The side facing you is the ascent route, although the true summit isn’t visible. After you cross the bridge to the south side of the river the road climbs, dips slightly, then rises again, all within about 500 m. The northeast ridge of the mountain, the ascent route, is above on the left. Allow 1–1.5 hours by bike to here.

Hike up through forest and talus slopes to the open ridge above. Continue along this broad ridge, which rises and becomes more clearly defined as you near some rock steps. While they may look questionable, these bands are easily surmounted except for the highest step, where you detour around to the left on a beaten sheep path. Apparently this peak does see visitors after all.

Above these rock steps the ridge again broadens and levels off. Behind you is a fine view of Threepoint Mountain, Mount Rose and the Big Elbow River. Trudge up to the high point above, from where you will see the true summit just west. Down over the south side lies a beautiful little turquoise lake not shown on the map. This false peak is a good spot to have a drink and study the final ridge to the summit.

Walk down scree to the col and scramble up the ridge to the top. In general, you can stay close to the crest, and only minor detours to the left are necessary. A couple of steps are steep, but they are short and not exposed.

The top is the ideal location to view the Banded–Cornwall–Glasgow traverse, especially the approach to Banded Peak. Far-off Mount Assiniboine is also apparent, and to the west a green carpet dotted with puddles of blue leads your eye to steep grey walls of Mount Rae. Rolling prairies disappear in haze to the east. After you’ve seen enough scree, scree and more scree, return to your bike the same way.

Cougar Mountain as seen on approach. Only the false summit is visible here. PHOTO: BOB SPIRKO

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling

Round-trip time: 8–10 hours to traverse

Height difference: 930 m between highest point and start

Maps: 82 J/15 Bragg Creek; Gem Trek Bragg Creek & Sheep Valley, Canmore–Kananaskis Village

The south end of Nihahi Ridge is a popular hike, but of the myriad hikers who set off, few parties undertake the entire 7-km traverse. When dry, much of this trip is merely traipsing along a breezy, rocky ridge, but occasional slabby places and short sections of downclimbing add challenge too. The view includes foothills, prairies and bigger peaks in the Kananaskis Front Ranges. This ridge is often in condition by late May, and for a season starter it’s worth the effort at least once.

Park at Little Elbow Recreation Area west of Bragg Creek on Highway 66. Parking is to the left before the campground entrance.

Walk west through Elbow campground past the gate and follow Little Elbow trail. One kilometre past the gate, Nihahi Ridge trail heads off to your right through forest to the south ridge. The hiking trail runs below the east side of the ridge for a distance before gaining the crest. Scramblers can gain this crest earlier to enjoy a panoramic view sooner. Scramble up at a point just past the first rock bluff.

Much of this route is little more than hiking. Periodically you’ll encounter rock steps that require a short scramble to get down, while the odd slabby spot adds further variety. It is straightforward when dry but harder when snowy. To the west, scramble routes up Mount Fullerton are visible, and Fisher Peak protrudes beyond it. To the east, Powderface Ridge and sprawling Moose Mountain intervene before prairie.

The traverse has its ups and downs, and as a result you must repeatedly lose and regain elevation. Although the highest points near the north end register about 900 m above the trailhead, you actually gain significantly more than that. If you tire of the whole game, descend easy slopes west to Nihahi Creek at any one of several points and hike back to Little Elbow trail.

Allow 5–6 hours to the north end high point at 458360, from where you have two possible descents. One is via west-facing scree slopes to the small, partly treed basin lying southwest. This is the source of the usually dry north fork of Nihahi Creek. You’ll see other obvious descent routes just west of this high point also. Then a long but worry-free trudge leads down dry Nihahi Creek to Little Elbow trail. Just before a canyon, the trail rises on the left over a shoulder. From Little Elbow trail it is about a 45-minute walk back to the campground.

Another exit from the north end of Nihahi Ridge is to descend north to Prairie Creek basin and hike east to Powderface Trail. Though lacking an established trail, this is a shorter return, but it does require a second vehicle at Prairie Creek, 9.5 km north of Highway 66–Powderface Trail junction.

Nihahi is a Stoney word for “rocky,” which aptly describes all 7 km of this ridge.

Difficulty: Difficult scrambling in places

Traverse time: 11+ hours, a long day

Height difference: 940 m higher than Nihahi trailhead

Maps: 82 J/15 Bragg Creek; Gem Trek Bragg Creek & Sheep Valley, Canmore–Kananaskis Village

Compression Ridge is the twisted sister to arrow-straight Nihahi Ridge. Only true masochists will consider going on from Nihahi Ridge to traverse horseshoe-shaped Compression Ridge. This long, tiring scramble is for experienced, capable parties with routefinding skills, not for those who require a trail. Two cars are necessary, as are dry conditions, good weather and long daylight. Try from June on.

Park a second car near Canyon Creek on Powderface Trail, 14.5 km north of the Powderface Trail–Highway 66 intersection. Be sure to study Compression Ridge’s northeast slopes for a descent route toward Canyon Creek and the road.

From Nihahi Ridge, problematic sections of Compression Ridge occur just before the highest point, at 436380, and east of there at a series of pinnacles. These are visible to the north across Prairie Creek basin from Nihahi Ridge. Continuing beyond Nihahi Ridge, travel is initially easy and promising. If you’re lucky you’ll find a welcome snow patch for water. Soon past the first major high point at 439364, difficulties begin. Turn a steep, rotten wall that has a slight drop immediately beyond it, by descending rubble on the left. Then a narrow but solid ridge leads to the highest point, 7–8 hours from Elbow Campground.

Beyond (east of) the highest point, steep steps and pinnacles appear, and like unruly drunks at a party, these are best avoided. Do this by descending and traversing scree and slabs on the right (south) side. Of note is a rock wall straddling the ridge displaying a large window clear through it. Skirt below this. Problems then diminish and just a long, tiring plod follows. If necessary, you could descend south slopes to Prairie Creek, but this would leave you many kilometres from either vehicle.

As you reach the final high point at the north end, you will notice scree slopes leading west to a side drainage of Canyon Creek. These would suffice as a descent, or, if you’ve checked from the road, descend the east side of the ridge. Just past the high point, drop down onto grey rubble followed by brown rubble. Near treeline a belt of slabs, unseen from above, can be descended in a couple of spots toward a treed knoll (458408). Steep cliffs block Compression Ridge’s north end.

It is an hour along typically dry Canyon Creek to your car. We took 11 hours for this trip in optimum conditions. With any snow remaining on narrow parts of Compression Ridge, it would NOT be a scramble.

The outing could also start at Canyon Creek and would be much the same level of difficulty. If travelling in that direction, you could always finish by walking out Nihahi Creek instead of traversing Nihahi Ridge if desired. The Spirko party followed Prairie Creek from the road to the col between Nihahi and Compression ridges, turned left and bagged the summit of Nihahi Ridge. They backtracked to the col, then headed north to the high point of Compression Ridge. Once past the window pictured above, a descent on obvious scree slopes to the east allowed a return via Prairie Creek again. This is a good option if you want a shorter day or have only one vehicle available.

Compression describes the forces that created the upthrust strata, tight folds and snaking S shape of this particular ridge. If straightened, it might be as long as Nihahi Ridge. Maybe even longer.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling with a short difficult spot along summit ridge

Round-trip time: 5–9 hours

Height gain: 1100 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village

In the past, parties have usually climbed The Wedge by steep technical routes on the west side, while the northeast ridge and face are used for a straightforward descent. Surprise! This moderately angled face makes an enjoyable scramble up, with the most fun occurring along the summit ridge. An acceptable approach trail leads to treeline and much route variation is possible once you reach the rock. Try from about June on.

Drive to Wedge Pond in Kananaskis Country, 30 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway on Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40).

Walk to the far end of Wedge Pond parking lot, past the locked gate where the paved bike path starts. Here a service road leads down to Wedge Pond. You do not need to go to the lake, although there is an access trail by the first culvert there. This way is better. After some 75 m, just before heading down to the lake, go left following a flagged trail into forest. This trail intersects an important drainage that comes down from a small basin below the steep northeast face and can be identified from the road by lighter-coloured poplar trees which grow amid the darker-green conifers. Once you’re on the left side of this drainage, a surprisingly good path leads upward to the open ridge above and the objective. Even if you weren’t ascending the peak, simply enjoying the view from the pleasant surroundings along the northeast ridge would be a fine way to fritter away a few hours.

A trail along the left bank leads to open slopes below the northeast ridge. After hiking up the grassy hillside to the crest of this ridge, Fisher Peak is immediately apparent to the southeast. As you tramp along the open ridge crest toward the northeast face of The Wedge, bleached and weathered wisps of tree trunks mingle with newer growth. According to Ruth Oltmann’s The Valley of Rumours… The Kananaskis, in the scorching hot summer of 1936, a careless camper’s fire at Kananaskis Lakes ignited the tinder-dry woods. The resulting inferno burned much of Kananaskis Valley, including this area.

As you reach the northeast face it is evident that the route is more laid back than suspected. Gain the slope at the easiest spot and move to the right edge of it as soon as possible, where you’ll find a beaten path amid the rubble. There are no difficulties in gaining the summit ridge, but once you do, the challenge increases as you scramble to the true summit, 15 minutes south. At the crux, the ridge narrows briefly and requires a short, exposed descent on loose terrain, but the remainder is easy after that.

From the top, you’ll see Mount Joffre’s snowy face to the south, while nearby lies the long, gently curving mass of Opal Ridge, yet another scramble. When you’ve seen enough, return the same way. Assuming you know how to self-arrest with an ice axe, in early summer you can sometimes glissade from near treeline down into the basin below the peak’s north end.

If you missed the approach trail, you might think “The Wedge” describes the difficulties of squeezing through tightly knit lodgepole pine trees, but the mountain’s suggestive shape is the true explanation.

The Wedge in June showing the ascent route as seen from near Evan-Thomas bridge.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 870 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Opal Ridge is an 8-km-long ridge paralleling Kananaskis Trail between Rocky and Grizzly creeks. Perhaps Opal’s most noteworthy features are the tightly folded strata visible in the steep west flanks above the road. These are particularly noticeable at the south end of the ridge as you drive north. For scramblers, this mountain offers variety, a view and easy access. You can ascend it from either end or midway along or traverse it. The traverse is recommended for competent scramblers. Owing to the ridge’s location and orientation, snow clears off quickly and you can sometimes head up as early as mid- to late April. Take an ice axe in early season.

Park about 1 km south of Rocky Creek bridge, on Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40) 35.7 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway. This is just south of Eau Claire campground.

Opal Ridge sits right above where you have parked. Rather than fight through close-knit pines and scrub bush infesting the lower north end of the ridge, it is preferable to scramble up open, steeper slopes right above the road. This avoids much of the feisty flora. Once on the ridge, continue south, rising through thinning evergreens. This forest leads to scree slopes below steep grey walls that guard the north end of Opal Ridge. Behind you The Wedge rears skyward.

Traverse around to the right for a short distance where a wide gully on the west side breaches the cliff band. Above the gully, go up over a bit of a shoulder, plod up more scree. A quick scramble then dumps you on the surprisingly flat top. The highest adjacent point lies slightly south and to reach it you’ll first scramble up a short 3-m-high wall. Here you will probably opt to sprawl out and enjoy the scenery before contemplating the southerly traverse. Fisher Peak dominates the eastern horizon, while the popular bowl route up Mount Kidd is evident to the northwest. Unless you plan to do the traverse, descend the same way.

Difficulty: Difficult scrambling, some exposure

Traverse time: 6–10 hours

Traversing Opal Ridge makes for a long but fulfilling day. Several high points along the way offer interesting challenges plus a little routefinding; other parts vary from tedious trudging to pleasant walking. One cliff band requires a significant loss of elevation to continue. The view throughout is terrific.

It is preferable to travel north to south, as a couple of the trickier places are more easily ascended than descended. Exposed sections are few and short, and while some difficulties are turned either left or right as required, others must be met head on. The north end is more involved. It is pointless to describe the whole trek in detail, but there are sections worth noting. Partway along, a high wall blocks the entire ridge. This requires a substantial descent toward the highway before you are able to finally overcome the troublesome rock band. This is the low point, both figuratively and literally. You must then trudge all the way up to the ridge again. If you’ve had enough fun by this point, this also looks like a feasible spot to bail out and descend to the road. Otherwise, the remainder of the traverse gradually shifts to enjoyable hiking as you approach the 2590 m high point (315275) directly above the Fortress Junction service station.

This is a fine rest stop. Kananaskis Lakes shimmer to the south, with Mount Joffre’s icy north face rising above a cluster of summits beyond. This panorama looks sublime in the gentle light of evening, and it could well be this late once you are here. Conversely, should afternoon thunderstorms be building, everything may be looking far too dramatic and have you worrying about getting down. Either way, most parties will be happy to head down here, especially if they have remembered to bring money.

Descent is easy. Backtrack northward toward the next bump, then charge down huge, shaley slopes, aiming for open terrain to the right (north) of the drainage. You can see these slopes plainly from the highway. The line of big rock pinnacles along the ridge poses no barrier, but don’t go into the drainage. The abrupt drop-off where the waterfall ice-climb called Solid Cold forms each winter will stop you short. Instead, keep right (north) and descend various trails to Fortress Junction. You may want to stash a bike to avoid the anticlimactic roadside plod back to Rocky Creek.

For anyone wanting to reach this 2590 m high point from the highway, the route starts directly behind a lone wooden utility building immediately north of the service station. Once you are beneath power lines, head north to cross the creek and follow the beaten path branching right which heads directly uphill. Diehards wanting to push on past the 315275 high point and continue to the far south end can do so. Grizzly Creek (unmarked at 311251, immediately west of Mount Evan-Thomas) affords a feasible route back to the road but is not nearly as fast as the shale slopes at Fortress Junction.

According to Place Names in the Canadian Rockies, by Boles, Putnam and Laurilla, Dr. George Dawson of the Geological Survey found quartz crystals coated with opal while prospecting nearby.

North end of Opal Ridge as seen from the road.

Opal Ridge south end showing route.

Difficulty: Easy to moderate scramble via southwest slopes

Round-trip time: 5–9 hours

Height gain: 2934 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village

The south peak of Mount Kidd is a pleasant ascent from the Galatea Creek trail. Parts of the trail disappeared in the 2013 flood but have since been repaired. This straightforward peak is rarely, if ever, busy. Try from June on.

Drive to Galatea Creek parking lot on Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40), 32.7 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway.

From the parking lot, cross the Kananaskis River, then a second bridge over Galatea Creek. At the T-junction turn left as for Lillian Lake. After about an hour you should be past the canyon and near or past an open area of downed trees on the left. Kidd South trail branches off to the right just past here at 253362 (cairn). This is about one minute before a wide washout which removed the original seventh bridge. The well-trodden path ascends a steep, grassy hillside to the right of a broad avalanche gully (250365). Continue up this gully through stunted poplars past a rock step to rubble slopes. Once above the trees, the easiest way up is across open, vegetated slopes to the ridge on the left. Near the summit ridge, skirt a couple of brief but steep rock bands, then slog up steep, coarse rubble. Notches on the ridge are bypassed on the right (south), whereupon the summit lies just minutes away. Return the same way.

An alternative, more scenic route from Guinn’s Pass is notably longer and much less popular, though the intervening ridge does grant a fine view of the lengthy scramble up Mount Bogart. Head east from the pass, traversing below the ridge crest on the south side until well beyond the first high point (237374). If you don’t, a steep drop-off will require much elevation loss and backtracking to circumvent it. The two routes join higher up. Return via the south slopes.

G: Guinn’s Pass route; GC: Galatea Creek route. PHOTO: GILLEAN DAFFERN

Difficulty: A moderate snow/slab/scree ascent via southeast bowl

Round-trip time: 6–9 hours

Height gain: 1350 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village

Mount Kidd has become very popular of late. It is a steep, unrelenting grind best done about late May or June when compacted snow allows step-kicking going up and glissading on descent. Otherwise, expect heaps of loose scree. Knowledge of ice axe self-arrest is imperative during prime months. Your safety also depends on accurate assessment of snow clinging to the steep walls above the bowl. Since much of the route is visible from the highway, most parties prefer to wait for a major or climax avalanche to occur before heading up. This is evident by large amounts of avalanche debris compacted into the lower third of the bowl and below the waterfalls.

If unsure of conditions, you should postpone your attempt until later when the climb will merely involve tedious scree and a bit of slab.

Drive to Galatea Creek parking lot on Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40), 32.9 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway.

From the Galatea parking lot follow the hiking path down the hill and across the suspension bridge over Kananaskis River. Continue for a few minutes through trees and over Galatea Creek to a directional sign and a T-junction. Take the right-hand fork for Terrace trail. Follow the trail as it parallels Kananaskis River on the east side of Mount Kidd, reaching a rocky streambed in 20 minutes. In spring this icy-cold brook is an ideal place to chill victory drinks for the return. Have a look – maybe you’ll find some!

Cross the streambed, then turn left onto a good trail in the trees which stays right of the rocky streambed as it heads for the huge bowl draining the east side. Scramble up the right-hand side of the waterfalls on firm rock ledges that lead into the wide bowl. This bowl is a classic example of a syncline, which here identifies the northern end of the ancient upheaval called the Lewis Thrust. The leftmost gully is least steep but slabbier due to the heavy rains of 2013. The next gully to the right is similarly easy once you’re in it, but you must traverse steeper slabs to reach it. A line of pinnacles separates these two routes. Though slabs and scree present few obstacles, the angle is unrelenting. Carry an ice axe if there is snow on this slope, and if new snow has fallen just prior to your attempt, you should probably go elsewhere. Slabs are slick when wet.

Be aware that snow-covered sections of this route may hide rock bands. Water flowing over these steps can weaken the overlying snow, and there is a very real hazard of falling into an icy, wet chasm between the rock and packed snow. Be watchful. A similar occurrence on Mount Niblock in June 1989 resulted in a fatality.

Although the incline is better suited to staring groundward, you may notice the peculiar window near the base of a high buttress along the skyline ridge connecting north and south peaks. While the south peak is also attainable from a different approach (described separately), this buttress along the intervening ridge prevents any possibility of traversing the two summits.

As you top out of the ascent gully, Mount Bogart rears up just across Ribbon Creek. A 10-minute walk up a stately ridge leads east to the true summit where now sits a telecommunications repeater. Early in the season, be wary of the massive cornice just beyond the cairn.

Fred and Stuart Kidd once ran a general store and trading post at the nearby settlement of Morley; the mountain was named for Fred.

The southeast bowl route on Mount Kidd as seen from Limestone Mountain. Conditions such as these would be ideal for step-kicking and glissading.

S: streambed; G: gully.

Difficulty: Difficult and exposed downclimbing near the summit; a climber’s scramble

Round-trip time: 10–14 hours with mountain bike approach

Height gain: 1570 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes and Canmore–Kananaskis Village

Fisher Peak is a high, sprawling mountain dominating the headwaters of Evan-Thomas Creek in Kananaskis Valley. As seen from the road, the long north ridge rises in a graceful arc to a series of three distant small bumps, the leftmost being the summit. Even the most direct route is long and has a difficult 25 m step. Compared to Mount Smuts, this crux is just as difficult but very different. An easier alternative route described in earlier editions is no longer feasible since the 2013 floods washed out the road. As of 2013, though, a bike can still be used for much of the first 7 km. Try from July on.

Drive to Evan-Thomas parking lot in Kananaskis Country some 28 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway on Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40). Fisher Peak sprawls in the distance to the southeast as you near the parking area.

From the parking area, the Evan-Thomas fire road is initially an easy pedal with a couple of quick detours into forest where the original road washed away in 2013. Travel is okay again, perhaps bushy/rough in places until reaching a side stream on the left. Cross bouldery debris to regain the road on the other side and continue. Once you begin descending a long hill with evident slumping and a big boulder on the road, you’ve almost hit the end of the trail. At the bottom of the hill, at about the 7-km point, not only has the road been washed out by a side stream, but the main valley has also been completely washed out and transformed into a gravelly, bouldery streambed (351356). There is little point in taking a bike beyond here. Head off on foot upstream, watching for the continuation of the fire road that diverges sharply to the right in about 1.2 km or so at 356348. The north end of Fisher Peak is visible here between the main washed-out valley and the much narrower side valley on the right, which you will now be heading into. Watch for cairns.

This continuation of the fire road deteriorates quickly, with one section washed out and much debris from side to side shortly after that. Along here is the logical point to head straight upslope on your left to gain the north end of Fisher Peak. As of 2013 this was right at a stretch where the creek flowed down the road but the road was still identifiable as such, 2.5–3 hours on foot from the parking lot or 25 minutes’ walk past the cairned turnoff point. Further travel upstream beyond here is, thankfully, not required.

Head up through open forest, crossing boulder fields to the broad ridge. This plateau hosts mosses, meadows and flowers – a pleasant surprise after the acres of debris! Wander south toward the summit mass. The plateau descends a bit, then rises into a better-defined rocky ridge with an increasing drop on your left. The crux step is unseen from here.

Seeing this step may leave you feeling disappointed, but look carefully: it can be downclimbed. First descend a short distance close to the crest, then traverse a few metres back to the left (as you face inward), more toward the south side. Descend a steep, 3- to 4-m-high wall in a corner. Arm strength and a good long reach are assets here. This is the crux; easier terrain leads to the ridge. Note that a short rappel would simplify matters. As you continue to the summit, one other, shorter notch must be downclimbed. Allow about 7 hours to the top.

From the summit, most striking is the substantial distance between you and the parking lot. Good thing you brought that bike after all. The return is via the same route. Climbing the crux will be much easier, but finding your bicycle again may be tough. On the way out, remember that horse riders use the road too, so please be courteous. Given the rough road it is unlikely you will be speeding, but watch for them and dismount until they pass.

John A. Fisher served as First Sea Lord of the British Admiralty, among other postings, and that was enough to have his name stuck onto a mountain forever. Only in Canada, you say – pity.

A summer skiff of snow on Fisher Peak as seen from the Mackay Hills. SSS: Serious scrambling section. PHOTO: SONNY BOU

Difficulty: A moderate scramble by south slopes from Ribbon Creek

Round-trip time: 7–11 hours

Height gain: 1680 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir (shown incorrectly on 2nd edition map; should be 1 km southwest, at 235412); Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village

Mount Bogart, the second-highest point in the Kananaskis Range, is one of the more recognizable peaks as you approach the Rockies from Calgary. The prominent triangular summit often holds snow when nearby mountains are bone dry. Although the view is excellent, the outing is long and uninspiring at times. Difficulties are few, however. Much of the 11-km-long Ribbon Creek Trail washed out in June 2013 but was rebuilt through volunteer help by summer 2015. Try from late June on.

Drive 23.4 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway on Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40). Turn right and follow signs to the Ribbon Creek parking lot.

From parking, follow the popular hiking trail beginning on the north side of this swift stream. This is normally a busy trail, but for this ascent you’ll probably be starting early enough to beat the rush. Continue along the wide path for 11 km to Ribbon Creek Falls. Beyond the campground the trail angles up from the base of the falls and switchbacks to cross a rock slide.

Leave the hiking trail once you reach the small stream coming down from a high valley at the south end of Mount Bogart (235395). You’ve come 10 km to here. This stream may not always be flowing. It is likely the section leading up from here will be eroded due to the 2013 rains, so the terrain may not be as described. Take animal trails up green slopes on the right-hand side. This gives way to rock above, where you should look for an easy place to scramble up an exposed, slabbier stretch. You then work back left toward the greenery. Shortly beyond, a ledge angling up to the right becomes a gully leading you to an unexpectedly large, meadowy cirque complete with alpine flowers and a tiny seasonal pond. This basin offers a perfect opportunity to relax and contemplate the rest of the ascent. Don’t be fooled by the foreshortened perspective of the route. The summit is farther away than it looks. After a couple of hours of slogging up a treadmill of scree, it will have become painfully obvious just how deceptive the earlier view really was. Upon reaching the rock band guarding the top, scramble up a narrow but prominent gully. This is the crux, so persevere, the end is in sight. Once you overcome this gully the terrain eases to a mere plod.

The summit vista includes many familiar nearby peaks in Kananaskis, and on a clear day visibility extends more than 100 km to the Purcell Range in BC. Closer at hand, a short hike along the ridge gives a bird’s-eye view of the three Memorial Lakes one airy kilometre below. These three ponds are the ultimate source of Ribbon Creek’s north fork.

Return the same way.

Mount Bogart is named for geologist Donaldson Bogart Dowling, who explored the area for the Geological Survey of Canada in 1904.

What a grunt! The Mount Bogart ascent route rises steeply from Ribbon Falls trail as seen before the heavy flooding of 2013. C: crux; D: descent.

Difficulty: Mostly moderate scrambling

Round-trip time: 5–7 hours

Height gain: 1240 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Mounts Lawson and Inflexible form a continuous 8-km-long escarpment of the Kananaskis Range along Highway 40. The peak sees somewhat regular visits now, despite the intervening kilometre of dense pine forest. You may even find a trail if you’re lucky. The preferred time is early season when a bit of snow still covers some of the ever-present loose rubble while also allowing a long glissade descent. Adjacent Mount Inflexible (3000 m) can be reached by the connecting ridge, although this outing has not proved popular in the past. As viewed from Fortress Junction, these two peaks are separated by a deep basin carved in the flank of the escarpment, with Lawson to the left. The first drainage gully to the left of this basin presents a direct line to the summit ridge. Carry an ice axe, as the approach slopes are steep. Try from about June on.

Access is from Fortress Junction, 41.8 km south of Trans-Canada Highway on Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40). Turn right, drive a short distance down the gravel road, which is gated. From the bridge, walk 10–15 minutes to the first switchback in the road. The trail starts just past the midpoint of the bend. The correct place is past an opening in the forest that heads left toward the highway, but before an orange metal survey marker just off the road in the trees. Watch for flagging between these.

The first step is to find the correct drainage. I previously suggested taking a compass bearing or a grid reference from the roadside in case the trail peters out, but this probably isn’t needed anymore. If in doubt, angle up fairly steeply as you traverse, to ensure you intersect the proper drainage rather than pass below it. The first drainage, the larger of the two, flows down well into the woods. Cross this to the second drainage, which is noticeably smaller and dry until you get farther up. Reaching this drainage from the first switchback takes about 25–30 minutes. As you ascend the streambed there are two waterfalls, which are bypassed to the right. Not long after, the alpine zone and larch trees are reached, granting an uninterrupted view of Kananaskis Valley against a backdrop of serrated Opal Range peaks. Mounts Denny and Potts, seen almost directly east, are other scrambles described in this volume.

Above treeline the slope is moderately angled and presents no serious problems. It is not as steep as roadside appearances suggest. Farther left, the angle steepens and involves scrambling instead of just trudging. In fact, with less rubble it might even be enjoyable. Slog up heaps of debris and short cliffs to finally reach the wide summit ridge. The high point lies a few minutes south. Beware of early-season cornices here.

To the west is a hidden valley, complete with a tarn tucked between parallel ridges of mounts Lawson and Kent. Much farther south and west are the impressive forms of mounts Joffre, King George and Assiniboine, all more than 3353 m. Determined souls can traverse north along the ridge toward Mount Inflexible (3000 m), but expect loose rock and several spots that require climbing down and back up overlying steep, rubbly slabs. Significantly more difficult, it adds about 300 m elevation gain just getting there. Most people don’t bother, and of those who have, apparently few have enjoyed it. I didn’t think it was that bad, but it does add four hours and much more elevation. For a simpler return from Inflexible, some parties have descended west toward the hidden valley, then climbed back up to the low point of the ridge, adding yet more elevation, but most would likely be happier simply ignoring the traverse. Enough said.

On the return, if you have your ice axe there may be an opportunity to glissade. With optimum snow conditions, an exhilarating sitting glissade of more than 500 m is possible, a quick and cheeky way of losing both elevation and excess body heat. Be sure you know how to control your speed and perform self-arrest: there has already been one glissading accident on this slope.

Major W.E. Lawson was a topographer with the Geological Survey of Canada; HMS Inflexible was a battle cruiser engaged in the Battle of Jutland. Clark Kent was a newspaper reporter with the Daily Planet.

The Mount Lawson ascent route is not as steep as it looks– but it’s still steep!

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling via the west face

Round-trip time: 7–11 hours

Height gain: 1425 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes

Unless you’ve scrambled to the south end of Opal Ridge you may not have seen Mount Denny (at 338277), neatly tucked away behind Opal Ridge and hidden from most roadside views. It can be seen briefly at one point along Smith-Dorrien Highway. This fun scramble leads to a double summit and is accessed by a steep animal trail up Grizzly Creek. The ascent is straightforward, starts from lovely high meadows and is unlikely to be crowded. Try from late June on.

Park at the Grizzly Creek parking area, 45 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway and 3 km south of Fortress Junction on Highway 40. Grizzly Creek, the approach drainage, lies exactly on the signed boundary between Spray Lakes and Peter Lougheed provincial parks. From parking, walk north toward the powerline right of way to pick up an obvious trail on the north (left) side of Grizzly Creek. This is the only logical approach for this peak.

Follow the animal trail as it rises steeply and stays well above Grizzly Creek. In places, this path is only a short distance below vertical rock ribs that descend from the south end of Opal Ridge, and you cross gullies of debris washed down from above. The trail leads past a wide gully with grey rock on the left, brown rock on the right. This can be ascended on the left side but gains unnecessary height. Continue instead to the next gully, turn left and tramp up it to a meadowy saddle between Mount Potts and Opal Ridge. If you continue up Grizzly Creek, you’ll find it dead-ends in the cirque formed by Potts and Evan-Thomas, the next peak south. Mount Denny, your objective, is connected to and just north (left) of Mount Potts.

From the Opal–Potts saddle, head north about 1 km, gradually losing elevation, and contour over to the right across open meadow and down to a scree cone below Denny’s west face. Notice the contorted rock forming an overhanging roof – early summer snowmelt creates a waterfall here. Just to the right of this roof, starting near the top of the scree cone, is rubbly terrain that gets you around and above the roof. Once above it, head toward the obvious long gully bisecting the west face. Much variation is possible on this face. Moderate slabs and scree on the right side of this central gully lead directly to the connecting ridge between two summits. Once you top out, the surrounding views really open up, especially over the back side. The summits are about equal in height and mere minutes apart. Mount Denny is an unofficial name given by a Glen Boles party upon making the first ascent of the north peak in 1973.

Energetic scramblers may decide to make an attempt on adjacent Mount Potts while in the area. For capable parties, it is feasible to do both Denny and Potts during the long daylight of summer but it makes for a very demanding day. Mount Potts is a steep, difficult scramble up a narrow gully, significantly harder than Mount Denny, and also involves steep slabs and ribs along the top. There is no easy descent route.

The ascent line begins from the back of the cirque between Mount Potts and Mount Evan-Thomas, the next peak south. The two summits are connected by a long, sharp ridge. From the saddle between Opal Ridge and Mount Potts you must give up elevation to get to the back of this cirque. Trudge over rubble past a small patch of green meadow to the big scree slope below a rock band spanning the cirque. In early season a trickle of water flows down here. Scramble up the rock band. Past that, we ascended via a brownish gully going steeply up to the left, though there may be other options. If you gain the connecting ridge between these two peaks by heading directly up from the back of the cirque, it will become obvious that the ridge to Mount Potts is not at all scrambler-friendly, just like the rest of Mount Potts. Furthermore, alternative descent routes often end in steep ribs and drop-offs, as we discovered when trying an adjacent gully (west), so plan on descending your ascent route.

Glen Boles named this peak for Jerry Potts, a scout and interpreter for the North-West Mounted Police after 1874.

The west face of Mount Denny from Opal Ridge, showing the ascent route.

Mount Potts and the steep, brownish gully route seen from slopes of Mount Evan-Thomas.

Difficulty: An easy scramble via south and east slopes

Round-trip time: 4–6 hours

Height gain: 2535 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir (unmarked at 328249); Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

This small summit sitting by Grizzly Creek is unnamed on maps, but Grizzly Peak bears inclusion for accessibility and the view alone. West of Mount Evan-Thomas and beside the road, it gives an outstanding view of the Kananaskis Valley, the Elk Pass area and vertically tilted Opal Range peaks. Sitting right above Kananaskis Trail, the steep, slabby west aspect looks daunting and reveals nothing of the easier back side. That side can be seen from a few kilometres farther south or along the south end of Smith-Dorrien Road. Sheep trails offer a reasonable approach. Try from about mid-June on.

Park on the side of Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40) at Ripple Rock Creek (unsigned), 1 km south of Grizzly Creek and 46 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway. This stream is midway between Grizzly Creek and Hood Creek, which are 2 km apart, both of them signed.

Above the stream on the left (north) side you’ll find a well-used animal trail paralleling the drainage and heading up the steep, open hillside. Start off on this. Don’t hike alongside the creek, as it is confined and bushy. Contour on hillside around the south side of the peak, above the stream but not so high as to encounter summit cliffs extending down. Some trails lead up into steep scrambling terrain and this is where folks can go wrong. The correct route may be steep sidehilling, but if travel isn’t technically easy, try lower down.

Make your way around the peak, crossing open slopes of scree and vegetation, then angle up toward the high saddle tucked between Grizzly Peak and Mount Evan-Thomas when it becomes visible. If you’re hoping for a nice level spot for a snack, you’re out of luck until this saddle. Until this point, terrain is relentlessly steep. If not for well-established grasses and small plants, it would surely have eroded away eons ago. Almost everywhere back in this basin are steep, grassy slopes. No wonder so many bighorn sheep are attracted to the area.

Once you reach the broad saddle, it is an easy 15-minute hike to the top. You might notice a lonely little larch tree that by some quirk has taken hold on this slope and managed to survive where none other has. From the top there is a fine view of the Kananaskis Lakes with snowy Mount Joffre behind. Nearby Opal Range peaks like Evan-Thomas, Packenham, Brock and Blane are easily studied from here, and to the north you can see The Wedge.

Deep rubble gullies on both the south side and the west face appear to be possible descent routes, but I would not recommend trying these. Opal Range peaks, because of their vertical bedding of strata, sometimes lure gullible parties down into innocent-looking scree gullies only to end in vertical drops. Once you’ve seen enough, return the same way.

Grizzly Peak’s south side seen from the Smith-Dorrien Highway. The route sneaks around to ascend the easy back side. Kananaskis Trail is to the left.

Difficulty: A difficult scramble by west ridge; exposure

Round-trip time: 8–10 hours

Height gain: 1500 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes

Mount Evan-Thomas is the highest peak of the Opal Range and can be done as a scramble, though not an easy one. The approach is the same as for Grizzly Peak. The west ridge involves a traverse of an exposed ridge crest, getting past two overhangs along the way, and slab/crack climbing near the summit. This route requires dry conditions and is not a scramble if snow persists. Try from late June on.

Park and approach as for Grizzly Peak.

Once you reach the saddle between Grizzly Peak and the objective, follow a sheep trail at the far right side of the long rubble slope leading to the west ridge. Above the rubble the terrain soon changes to a well-defined ridge with a series of “bumps” visible ahead. These are all overhangs to some degree, caused by a softer layer of rock on the east side having eroded away, leaving harder limestone layers standing nearly vertical. Bypasses to the right exist for the first distance until you reach the main crux, a pointy slab that stands tall and overhangs the narrow ridge. There is no apparent easy way down the east side. Most folks would choose to detour around this by backtracking and descending gullies and slabby rock on the south side until able to traverse across and back up to regain the west ridge beyond the overhang. So the easiest option, tedious as it may be, is to backtrack some distance down the ridge and descend a wider gully, losing a significant amount of elevation, to get into an obvious but narrow gully which feeds Ripple Rock Creek below. This drainage would be difficult to ascend directly from the approach route. Although narrow, it leads straight up and back onto the west ridge again and can be seen from Smith-Dorrien Highway. You emerge beyond the crux.

Once you are past the main crux and at least one more bump, the second problematic overhang awaits at a more level stretch before the final ridge to the summit. This crux can be carefully downclimbed on the east side. It is not as difficult as it looks. Holds and ledges are present where needed, but beware of loose pieces. Continue easily along the ridge. The steep gully on the south side of the ridge along here was the descent route of the first ascenders in 1954: J. Farman, M.S. Hicks, W. Lemmon, G. Ross, I. Spreat and J.F. Tarrant. It has since been used as an ascent route by Nugara, Bou and others. You reach that gully by leaving Ripple Rock Creek on the approach and angling to the right, going over a hump into the basin between Evan-Thomas and Mount Packenham, the next peak south.

Beyond the level section of west ridge the angle steepens as you near the summit. Scramble up an obvious crack below and left of the summit block, one last challenge before you top out. The summit provides wonderful views over much of K-Country as well as farther west toward big peaks such as Mount Assiniboine.

Most parties return the same way, although you could also descend the previously mentioned steep gully on the south side taken by the first-ascenders.

Rear Admiral Sir Hugh Evan-Thomas was commander of the Fifth Battle Squadron at the Battle of Jutland, according to Canadian Mountain Place Names.

Mount Evan-Thomas from the Smith-Dorrien Highway, showing the route from Grizzly Peak saddle and the gully bypass route. P: crux pinnacle; G: bypass gully; DG: descent gully of first ascenders.

A scrambler approaches the crux pinnacle P along the ridge to Mount Evan-Thomas. Bypass route B descends to the right to circumvent it.

Difficulty: A moderate to difficult scramble via east side; loose rock and exposure

Round-trip time: 3.5–6 hours

Height gain: 780 m

Maps: 82 J/11 Kananaskis Lakes; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Gap Mountain is indisputable proof that bigger isn’t always a better viewpoint. This little peak is close to the road and over half the elevation is gained by merely hiking. Because of the exposure and steep slopes of loose rock, this scramble is recommended only for small parties of experienced, competent scramblers. An early start is not required for this little peak but a helmet is worthwhile. Try from July on. Note: The access road here is sometimes closed due to grizzly activity. Check the status of Valleyview Trail in Peter Lougheed Park before setting out.

Park at Little Highwood Pass day-use area at the east end of Valleyview Trail, 6.4 km west of Highwood Pass and 10.6 km southeast of Kananaskis Lakes Trail–Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40) junction.

From the parking area, walk about 300 m west along Valleyview Trail and head off to the right into forest. You should be close to either one of two gullies that drain from an open pass set between Mount Elpoca to the east and Gap Mountain to the west. Gain this pass, which then provides access to the east side of Gap Mountain. Travel through forest is easy and occasional sheep trails aid your short approach.

The pass is a fine viewpoint and an ideal spot for a break. Here you can admire the hidden alpine basin that feeds Elpoca Creek tucked below vertical walls of mounts Elpoca and Jerram. Beyond, jagged Opal Range peaks parade northward. You can also study the route up the east side of Gap Mountain, although the perspective does suffer from foreshortening. From where the ridge abuts the mountain, a bit of trail leads up slab and rubble toward the first steep wall. Now angle left to gain a much broader gully. A brief exposed traverse takes you around a corner, crossing downsloping rock above a deep, steep gully. It is only about three or four moves but a fall would be deadly. Parties have scrambled up almost directly above the abutting ridge and also from points farther to the right.

Continue up steep rubble and shattered, downsloping slabs. Terrain to the left is easier-angled. Care is needed, as the rock is extremely loose in places and there is rubble on slabs and ledges. By now it should be evident why this is not a good group objective: dislodged debris falls straight onto parties below. Once you get onto the ridge above, the slope lays back and the fabulous Kananaskis Lakes panorama unfolds. The rest of the way is obvious and you can either continue up the ridge crest or along scree to the top.

Major peaks on the skyline include snowy mounts King George, Sir Douglas and Assiniboine, with snowcapped Mount Ball farther north. Behind, the road winds east up to Highwood Pass. With binoculars you may even see tiny people trudging up the summit ridge of Mount Rae, or perhaps tiny people on Mount Rae staring with binoculars toward Gap Mountain. Whatever the case, on a clear day the top is an excellent viewpoint. Resist the urge to descend gullies on the west side. West-facing gullies on Opal Range peaks usually end in vertical drops and therefore do not make good descent routes. Return the same way.

Routes on Gap Mountain. C: Common easier variation; O: Original route; S: Spirko route; K: Kane variation.

Difficulty: Moderate/difficult depending on route; possible exposure

Round-trip time: 7–11 hours

Height gain: 1020 m

Maps: 82 J/11 Kananaskis Lakes; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

The 82 J/11 map 2nd edition incorrectly shows Tombstone Mountain at 407165. Tombstone has a double summit and is actually 1.5 km to the northwest. This scramble ascends the peak at the above coordinates, unofficially called Tombstone South.

Tombstone South, tucked in behind the Opal Range, sits in lovely subalpine surroundings not far from ever-popular Elbow Lake. The readily approached south ridge is an enjoyable scramble, and despite unavoidable scree in places, much of the ascent is on delightfully firm slabs. A route staying close to the edge of the ridge is airier and in places the scrambling level approaches difficult. While you may well encounter crowds at Elbow Lake, you won’t meet many people on this peak. The summit view is excellent, surroundings are serene and bush is minimal. A mountain bike saves time but the trail is always rough. Try from July on.

Drive to Elbow Lake trailhead on the north side of Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40), 12.3 km southeast of Kananaskis Lakes–Kananaskis Trail junction.

From the parking lot a steep trail ascends the hillside, gaining elevation quickly. Bikers will probably push up this bit. The trail soon eases and reaches Elbow Lake in a mere 1.3 km, where you’ll find a backcountry campsite along the right (south) shore. This campsite is an ideal base for day trips to this peak, Tombstone Lakes and hikes nearby. Continue down the left (north) shore past the lake in wide open subalpine surroundings. Mount Elpoca, with its spectacular towers high above, is along your left side, and to the right is Mount Rae and tiny Rae Glacier. Tombstone South lies pretty much straight down the valley, and the right-hand ridge is the route of ascent.

About 4.5 km from the parking lot you should be near the peak’s south ridge. A cairned trail to Piper Creek flowing below the peak exists here; otherwise, simply head left directly toward the peak, boulder-hopping or wading the Elbow River (or stream!). Expect a stint of fir forest near the peak if not on the trail.

Once on the ridge, the best scrambling follows the crest up firm slabs much of the way. Loose scree is absent until higher up, while exposed spots can usually be detoured to the left. Behind in the distance is Mount Tyrwhitt, while all about you a luxuriant carpet of green unfurls. Higher up, a rock band bars the ridge and you should angle across the scree to a low point where it is easily overcome. Head back up on loose rubble toward the ridge and soon reach the false summit. The connecting ridge makes a slight descent before reaching the true summit, minutes away.

Peer carefully over the east side: the gut-wrenching drop to Tombstone Lakes will snatch your breath away. The jagged Opal Range, not typically viewed from an easterly aspect, juts skyward to the west. Mount Jerram, in particular, looks impressive. Neighbouring Tombstone Mountain was named by George Dawson for rock pinnacles near the summit that look like tombstones. Mighty Mount Assiniboine pierces the skyline to the northwest, while the glaciated east face of Mount King George identifies the Royal Group.

You may have noticed the apparent ease of descending the southwest-facing slopes beneath the summit. They converge into a gully at the bottom. Coarse rubble with stretches of slabs comprises this descent and much variation is possible. With luck you will strike a well-beaten trail at treeline leading around the base of the peak. When appropriate, simply shortcut through the forest again to reach Elbow trail.

Tombstone South ascent and descent routes as seen from Pocaterra Ridge. PHOTO: BOB SPIRKO

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling via west slopes and south ridge

Round-trip time: 7–11 hours

Height gain: 1300 m by King Creek approach; 1450 m by King Ridge

Maps: 82 J/11 Kananaskis Lakes; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Mount Hood is one of the less conspicuous peaks in the Opal Range. Despite the lack of technical difficulty, it is not a high-traffic mountain. The bushy approach discourages the casual wanderer, and because it is not evident from the road, it does not attract as much interest. Most Opal Range summits require roped climbing, but this is one of the few viable scrambles of the group. Try from late June on.

Drive to King Creek, 52.5 km south of the Trans-Canada Highway on Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40).

There are two possible approaches to Mount Hood, but oddly enough, nearby Hood Creek is not one of them. King Creek has been the normal approach in the past, though it was not particularly pleasant due to downed trees and rock debris from flooding, lack of a decent trail, and creek crossings in the canyon. The June 2013 floods made it worse yet, but here is the route if you do choose this less desirable approach.

Muddle through King Creek Canyon, and when it forks, turn left and follow it north below steep, green slopes hosting numerous sheep, goats and occasional grizzlies. Continue to the far end and reach a broad saddle between Mount Hood and King Creek Ridge to the west. This approach has much debris, especially through the canyon, and then more rock debris along with bush and trees beyond. Allow 3–4 hours.