Little Hector 3125 m moderate

Mount Andromache 2996 m moderate

Dolomite Peak 2998 m difficult

Cirque Peak 2993 m easy

Observation Peak 3174 m easy

Mount Weed 3080 m moderate

Mount Chephren 3307 m difficult

Mount Sarbach 3155 m difficult

Mount Coleman 3135 m difficult

Nigel Peak 3211 m moderate

Mount Wilcox 2884 m moderate

Tangle Ridge 3000 m easy

Sunwapta Peak 3315 m easy

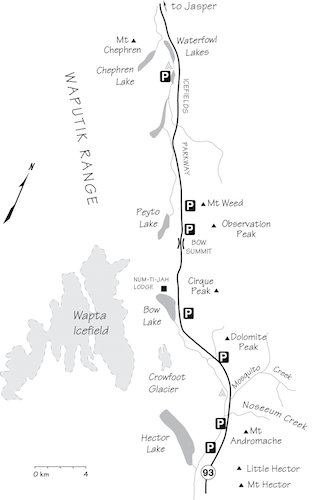

Peaks in this chapter border the Icefields Parkway (Highway 93) joining Banff National Park to neighbouring but larger Jasper National Park. The Parkway has rightly been called the most scenic drive in the world. Visitors gasp, awestruck, at craggy, towering peaks cloaked in glaciers soaring far above the highway, and each bend in the road unveils new wonders. This is particularly true of the southern half of the 232-km route. For many, the biggest thrill lies at the Columbia Icefield.

The Columbia Icefield is a sea of glaciers and icefalls straddling the Continental Divide. Depending on your information source, it varies from 325 to 200 km² in extent, and in fact it may well be shrinking even as you read this. Many of the Rockies’ highest peaks are found here, including Snow Dome, which rises nearly 3500 m. This peak is truly unique, as it is the hydrographic apex of North America. Its snowmelt flows in three different compass directions to eventually empty into the Pacific, the Atlantic and the Arctic oceans. The icefields are local mountaineers’ favourite playground and the area is often used as a pre-expedition warmup for world-class alpinists. Less adventurous (more sensible, some would say) folks can ride snowcoaches out onto Athabasca Glacier for a first-hand inspection. Fools sometimes wander up from the toe of the glacier parking lot, ignoring posted warnings, and occasionally somebody falls in a hidden crevasse and dies. Remember, this icefield is a spectacular, but dangerous, marvel.

Although many peaks along the parkway are technical ascents, easier ones exist too. The highest scramble in this chapter is Mount Chephren at 3307 m. Because of its height and location, snow lingers and the peak has a very short scrambling season. Mount Wilcox, behind the Icefields Centre, is highly recommended. On a clear day, the view over the icefields is outstanding. As the Icefields Parkway lies close to the Continental Divide, precipitation is high. The largest amount occurs at the Columbia Icefield: more than 900 mm annually – twice that of Banff or Jasper and half again as much as Lake Louise. Statistically, the odds of a clear day at the icefields are about one in four. Count yourself lucky if you visit it in sunshine. With a mean annual temperature of −2°C (yes, minus two; told you it was mean!), small wonder so much ice prevails.

Access The region is reached via the Icefields Parkway, Highway 93, which intersects the Trans-Canada Highway 2 km west of Lake Louise, then travels northwest for 232 km to Jasper. Meeting it at Saskatchewan Crossing is Highway 11, the David Thompson Highway, which runs east to Red Deer. Highway 16, the Yellowhead Highway, joins Edmonton and Prince George, BC, via Jasper. As for transportation, Brewster operates a daily shuttle from Calgary to Jasper; Via Rail trains stop in Jasper from Edmonton and Prince George, as do Greyhound buses. This is all extremely fascinating, to say the least, but to really do much, you need your own set of wheels – preferably four with a motor attached.

Facilities Few businesses are found along the Icefields Parkway and most cater to the sightseeing tourist with a fat wallet. Supplies are generally limited. Buy whatever you need in either Jasper or Lake Louise, including fuel. Gas is available at Saskatchewan Crossing and Sunwapta, but due to the location, expect somewhat higher prices. Cafeteria and restaurant meals are available in the Icefields Centre. If nothing else, the interpretive displays at the centre are worth seeing. Saskatchewan Crossing has a limited selection of groceries, several more postcards than you will probably need and a restaurant which has proven to be a nice change from camping food. This is a very busy place when tour buses stop in, which happens regularly.

Accommodation Lodges, cabins and chalets along the parkway are typically expensive and booked up. For the budget traveller, however, many campgrounds and hostels can be found along the way and in Jasper. All are popular during summer and fill up fast. Two campgrounds are close to the Icefields Centre: the Icefields campground, the smaller of the two, is where climbers and cyclists often share a picnic shelter on a wet evening or may even sublease space on a tent pad! Motorhomes are not allowed here. Located 2 km south is the larger Wilcox campground. Additional campsites are found along the parkway at Mosquito Creek, Waterfowl Lakes, Rampart Creek, Jonas Creek, Honeymoon Lake, Mount Kerkeslin, Wabasso, Wapiti and Whistlers.

Information The Icefields Centre is an impressive facility built in 1997 in conjunction with Brewster Travel, which operates the snowcoaches. Their info centre is the only one along this road: 780-852-6288. Parks staff are helpful regarding local conditions on both climbs and scrambles and also provide weather forecasts.

Warden offices are just south of Saskatchewan Crossing, at Sunwapta Falls, east of Jasper toward Maligne Lake and in Lake Louise Village. Wardens can also provide information to help keep you out of trouble.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling

Round-trip time: 6–9 hours

Height gain: 1260 m

Map: 82 N/9 Hector Lake (unmarked at 502155)

Little Hector is an unofficial name for a peak 2 km northwest of but attached to Mount Hector. Mount Hector, at 3394 m, requires glacier travel; this adjacent summit offers a similar view but avoids the glacier. When viewed from farther north at Mosquito Creek bridge, the peak has a striking pyramidal shape and the route up is clearly visible. The approach is short and you can descend by a slightly different route for variety. Try from about mid-July on.

Park in a small roadside pullout on the west side of the Icefields Parkway at Hector Creek, 20 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway and 3.3 km south of Mosquito Creek.

Cross the road and follow an obvious trail on the right (south) side of Hector Creek through forest, going left when it meets a wider trail. The trail soon emerges into the open below a waterfall and crosses to the left side of the stream. Scramble up easy ledges to the left of the next waterfalls. Move right, then cross a small stream, whereupon you enter a pleasant, open basin between Little Hector (502155) on the right and Mount Andromache above on the left.

From here you have a fine view toward the objective, although the perspective is very foreshortened. The idea is to continue upvalley along the right side for a short way and pick a good spot to ascend steepish slopes on the right. This is the north end of Little Hector. If you continue east too far, the rock below Little Hector becomes too steep to ascend. We chose to ascend the slope just before a cliff band of overlapping rock layers descends from Little Hector and forms a headwall across the valley. This slope, mentioned above, may be less steep. Depending on where you choose to head upward, expect masses of rubble with possible sections of waterworn, downsloping slabs – slick when wet!

As you gain height, the view becomes more breathtaking with every step, with Hector Lake and Mount Balfour competing for camera time. The final slope to the top is gentler-angled but still loose and rubbly. A few thousand feet tramping up and down might help stabilize it a little! Once you reach the top, it becomes obvious why this peak is not noticeable from the south. A long, almost horizontal ridge connects to higher Mount Hector, and were it not for the glacier farther up, Hector too would be a scramble. Unless you are equipped for glacier travel, though, you should not continue. There are crevasses and a bergschrund. You should also be aware of the possibility of a cornice on the east side of Little Hector.

This summit is strategically located and many major peaks are visible from it. Giants of the Lake Louise group like Lefroy, Temple, Victoria and Hungabee cluster together, with the Goodsirs and Mount Stephen close by. Other features that contribute to sensory overload are the Wapta Icefields and pointy Mount Chephren farther up the Icefields Parkway.

On descent, perhaps the quickest way is via a wide gully of rubble facing northwest below the summit. Head back down the slope you tramped up and continue descending into this broad gully. The well-defined ridge alongside it on the left aims for the road and may seem tempting to descend, but it is not just a simple walk, whereas this gully is. Trudge down it almost to treeline, then contour left, going around the end of a ridge (animal trails in places). Gradually lose elevation as you work your way around left and down toward the highway below. Bushwhacking is no problem and the descent may take only a couple of hours in total.

Evening light on Little Hector as seen from the road a few kilometres north. Mount Hector rises behind.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling

Round-trip time: 8–10 hours to traverse

Height gain: 1160 m

Map: 82 N/9 Hector Lake (unmarked 492182)

Mount Andromache (An-DROM-a-kee) is an easily approached peak alongside the Icefields Parkway that gives a fine view of nearby Hector Glacier. As the title is unofficial, it is unnamed on the map. In the past it has not been a well-known objective, but that should not stop real peakbaggers. The approach distance is short and the view is magnificent. A traverse allows you to cross a higher unnamed point along the way. Try from July on.

Park in a small roadside pullout on the west side of the Icefields Parkway at Hector Creek, 20 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway. The traverse finishes about 2 km north at Noseeum Creek.

Not everyone thinks it is better to ascend this peak from Hector Pass but most parties agree because the loose north ridge of Andromache is so tedious on ascent. If they haven’t already done so, those who disagree could try it in both directions and compare.

Cross the road and follow an obvious trail on the right (south) side of Hector Creek through forest, going left when it meets a wider trail. The trail soon emerges into the open below a waterfall and crosses to the left side of the stream. Scramble up easy ledges to the left of the next waterfalls. Move right, then cross a small stream upon which you enter a pleasant, open basin between Little Hector (502155) on the right and Andromache above on the left. Hector Pass (510168) is due east. Stay left and traverse hillside on scree below Andromache and the adjacent Unnamed peak. The terrain flattens out toward Hector Pass. Scramblers need only go until the rock bands above on the left peter out. Turn left and trudge up the slope to gain the Unnamed peak straight above. The view of Hector Glacier is spectacular, while double-peaked Molar Mountain rises majestically across the valley to the east.

To reach Mount Andromache (492182), you can readily continue in a northwest direction along an open ridge. Despite what some maps show, ice does not cover the connecting ridge. The small Molar Glacier does abut the north side of the peak, though, so scramblers should avoid it and stay on the scree. Allow 30 minutes from the unnamed peak. The panorama from the top is magnificent, with Hector and Bow lakes adding much colour to the landscape of craggy peaks and glaciers to the west.

On the return, you have the option of either retracing your steps or completing a traverse by descending the mountain’s broad, rubbly northwest ridge. This descent is without problems and leads down scree to the highway by Noseeum Creek, 2 km north of Hector Creek.

In Greek mythology, Andromache was the wife of the noble hero Hector. In Canadian mountain lore, however, Mount Hector commemorates Dr. James Hector of the Palliser Expedition. His wife was not Andromache, which perhaps explains the absence of official endorsement for the name.

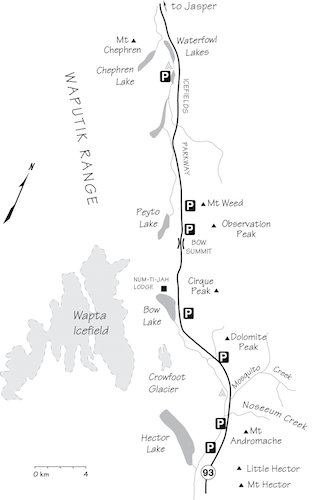

U: Unnamed; A: Andromache; L: Little Hector; H: Hector. Routes start near P: Hector Pass.

U: Unnamed and H: Hector Pass viewed from Little Hector. Mount Andromache is to the left.

Difficulty: Difficult scrambling; some routefinding necessary

Round-trip time: 5–7 hours

Height gain: 990 m

Maps: 82 N/9 Hector Lake; Gem Trek Bow Lake–Saskatchewan Crossing

Dolomite Peak is a recommended scramble close to the road, with the best part at the top. Despite much rubble on the lower slopes, rock on the upper section is generally firm and the summit view is spectacular. Dolomite is an altered (and improved) form of limestone, appreciated by climbers because of its solidity. Here it occurs in the top 300 m or so of the mountain. Steep towers give exhilarating scrambling, but all are not as difficult as glances suggest. As the strata are bedded almost horizontally, so too are ledges, and despite the ever-present Rockies debris, the last few hundred metres are a fine finish. This area has been closed in the past because of grizzly activity, so don’t be surprised if you find a closure sign. Check with Banff Park wardens at Lake Louise and have an alternative objective just in case. Try from July on.

Approach via the normal winter ski trail to Dolomite Pass (unsigned), beginning at Helen Creek, 28.5 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway on the Icefields Parkway. Park at a small gravel parking area at the north end of the bridge.

From parking, the trail heads steeply up over a ridge, then angles down and crosses the stream. As you hike along you should note the exact outline of the tower you are aiming for, as there are many. The highest point is the fourth tower from the north. You may even want to drive farther north to positively identify its specific shape. After about 25 minutes you’ll come to the second avalanche slope, about five minutes beyond the stream crossing.

There are many ways up the open shale slopes of the lower flanks, but if you hike the trail farther and ascend the fourth avalanche slope, it leads more directly toward the proper ascent gully between towers 3 and 4. If you ascend avalanche slopes sooner, it will require miserable sidehilling as you traverse north (left) to reach the gully. Some of the terrain is tediously loose on the lower slopes. At the summit mass a cairn marks the correct gully.

Once you’re directly beneath these towers, foreshortening makes it hard to decide which is which. The fourth tower is wider than either the third one or the fifth, and the right-hand side of the second tower shows an impossibly steep and smooth buttress rearing skyward. This is perhaps the most recognizable feature of any of the towers from this shortened perspective.

The proper gully should be the widest one you come to. Ascend this gully to just past the spot where a 3-m-high wall of rock briefly divides the channel of debris like a shark’s fin out of water. This is about 12–15 m below the top of the gully. Gain rubbly ledges on the right-hand side and work your way around to the right on these ledges in a rising traverse into another smaller gully (cairns). Go straight up rubbly ledges and a bit of steep but enjoyable scrambling, which leads to the double summit of the tower. There is room for route variation and the rock is sound, but several years of increased visitation by scramblers has loosened much more rubble. You should consider wearing a helmet, especially if you are with a group.

Tower 3 can also be reached from near the “shark’s fin” in the gully. It is easiest to traverse north (left) on a wide scree ledge below the top and then scramble a short distance up rock steps to the summit.

The view from Dolomite Peak encompasses the complete spectrum of mountain landscape, from drab, crumbling peaks to the east, to shining glacier-clad summits piercing the Wapta Icefield in the west. In between lie the emerald greens and azure blues of alpine meadows and lakes. Dominant mountains include Willingdon, Hector, Temple, Balfour, Chephren and Cline. Even distant Mount Assiniboine is visible on a clear day. A camera is essential.

The quickest descent is straight down the middle of the 3–4 gully to Helen Creek. Two short rock bands lower down require brief downclimbing, probably toward the right (north). Fine shale in places gives the knees a respite and you can expect the return trip to take less than half the ascent time.

In 1899 Dolomite Peak was named for its resemblance to the European Dolomites by Ralph Edwards, a well-schooled English transplant who was periodically employed by Banff packer Tom Wilson. On this occasion, he was accompanying “dudes” on a climbing and exploration trip up the Pipestone River toward the Siffleur River and Bow Lake. Today, adjacent mounts Thompson, Noyes and Weed commemorate members of the excursion. Lakes Helen and Katherine near Dolomite Pass were named after daughters of a fourth party member, Harry Nicholls.

Dolomite Peak, showing routes to towers 3 and 4 (highest).

Difficulty: An easy ascent, largely hiking

Round-trip time: 5–8 hours

Height gain: 1050 m

Maps: 82 N/9 Hector Lake; Gem Trek Bow Lake

Cirque Peak is a popular route and is approached via an even more popular hiking trail leading to classic alpine surroundings. Most of the route is a trudge up rubble on a well-worn path. There are no difficulties and the mountain sees occasional winter ascents too. The views include major icefields nearby and distant summits such as Mount Assiniboine 70 km away. This area is sometimes closed due to grizzlies. Try from July on.

Drive to Helen Lake–Dolomite Pass trailhead on the Icefields Parkway, 33.2 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway and 7.8 km south of Bow Summit. The parking lot is on the east side of the road.

Hike the well-graded trail for 6 km to Helen Lake. While it is tempting to merely fritter away the day lounging in these lovely alpine meadows by this lake, the view is much better from the easily attained summit of nearby Cirque Peak. Continue along the well-worn trail past Helen Lake, up onto the ridge and then left to Cirque Peak. With every metre gained, a wider and better panorama of the Wapta Icefields unfolds to the west. To the southeast lies Mount Hector under a blanket of ice. A ski ascent of this glacier is a popular undertaking for winter mountaineers bent on bagging the Rockies peaks higher than 3353 m (11,000 ft.).

The east peak of Cirque is marginally higher and often has a register. Allow 1.5 hours from Helen Lake and less than half that for the rapid descent. The name “Cirque” describes the amphitheatre formed by adjacent peaks.

Cirque Peak is an easy and rewarding ascent in beautiful alpine surroundings.

Difficulty: Easy/moderate scrambling

Round-trip time: 5–9 hours

Height gain: 1100 m

Maps: 82 N/9 Hector Lake; Gem Trek Bow Lake–Saskatchewan Crossing

From Observation Peak the view across Bow Lake to Wapta Icefield is spectacular to say the least. The west side of the mountain, by the road, is largely scree, particularly south of the described ascent route, so there are many possible ways up. Try from late June or July on.

Park on an old gravel road on the east side of the Icefields Parkway at the crest of Bow Summit, 41 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway.

Walk along the old road to just past a sharp bend to the left, then follow a major gully left of an avalanche zone and bush. Halfway up the peak are short cliffs, barely noticeable from the valley. Although they look problematic as you approach, you can easily dodge these around the right side on ledges (cairns). Similarly, you could avoid them entirely by starting your ascent slightly farther south and reduce the trek to nothing but endless rubble. Above half-height the slope becomes more ridge-like. Continue to the false summit, watching for large cornices that overhang the east side. These can prevent you from continuing. Descend slightly and plod 20 minutes northwest to reach the spacious summit, which is about 100 m higher.

Charles Noyes, a Boston clergyman, made several Rockies first ascents, including nearby Cirque Peak and Mount Balfour. He observed that this peak was one of the best viewpoints his party had attained on their exploratory foray of 1899. You will likely see why. A careful squint will reveal several significant summits such as Sir Donald, Forbes, Assiniboine and Hector. To the west, the surreally milky-blue waters of Peyto and Bow lakes lend a feeling of sublime tranquillity.

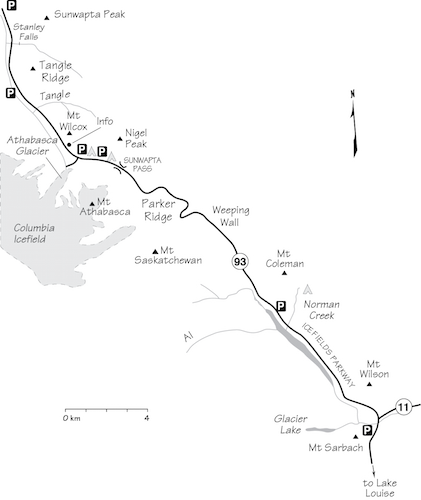

Observation Peak. G: gully; F: false summit; S: true summit.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling via south side

Round-trip time: 6–9 hours

Height gain: 1340 m

Maps: 82 N/15 Mistaya Lake; Gem Trek Bow Lake

Mount Weed sits adjacent to the Icefields Parkway, immediately north of Bow Summit. Despite its close proximity, this fine viewpoint does not see all that many ascents and falls in the category of a good “getaway” peak. The approach is straightforward and views from the top are absolutely fabulous. Try from July on. Ice axe required if snowy.

Park at a small pull-off area on the west side of the Icefields Parkway, 7 km north of Bow Summit and 48 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway. Mount Weed rises directly to the east, and the ascent route is readily seen as you drive north from Bow Summit.

From the parking spot, walk north along the road for about 5 minutes (500 m) then head east into the forest, quickly arriving at a drainage. Follow the right-hand side of the drainage through forest. As you approach the first rock band, visible from the highway, leave the creek and ascend slopes to the right. Almost immediately the drainage splits and you can see that the left branch becomes a canyon. You should instead follow the right-hand branch, now a dry, rocky gully. By continuing straight up this gully you will avoid any further cliffs and it will lead to an open avalanche slope and the base of the final gully. If you’re on the correct avalanche path, you’ll notice two huge boulders side by side near treeline, one as large as a small house.

From the boulders, plod straight upslope on good scree toward a big gully. Glancing behind reveals a view of Bow, Peyto, Mistaya and Waterfowl lakes, not to mention an ever-increasing array of summits and icefields. As you reach the summit cliffs, there are 400 vertical metres to go. With firm snow, the gully would be fine for step-kicking; otherwise, expect tiring scree. Either way, rockfall is a hazard, and scrambling up ledges to the right is preferable. The terrain eases at the top, but beware of cornices in early season.

A few of the peaks visible are mounts Columbia, Cline and Forbes and the Lyell and Mummery groups. Multi-pinnacled Mount Murchison lies just north, while the Lake Louise group rises to the south. Return the same way; the gully will now be faster.

G.M. Weed accompanied C.S. Thompson on explorations in the area in 1899, making the first ascent of Cirque Peak along the way.

Telephoto view of route from Bow Summit area.

Difficulty: Difficult for a short distance even if dry; ice axe suggested

Round-trip time: Two days or one very long day

Height gain: 1700 m

Maps: 82 N/15 Mistaya Lake; Gem Trek Bow Lake

Mount Chephren is a stunning eye-catcher situated along one of the world’s most scenic drives, the Icefields Parkway. Mountains tower along both sides of this road, although most are not as accessible as this one. The summit view is unequalled, but the massive height and location of this pyramidal giant makes it a serious endeavour. Granted, mounts Temple and Stephen feature more elevation gain, and the path down the left-hand (east) shore is not as good. The right-hand shore is wicked bushwhacking that you should avoid entirely. To surmount the first cliff band, even the easiest spot will involve scrambling up steep, exposed terrain, but for fit, capable parties equipped with ice axes, this ascent is highly recommended. As a day trip, an alpine start by headlamp is suggested so you can be well up the south-facing slopes before the full heat of the day hits. This is a mid- to late-summer ascent, when hopefully the route will be snow-free. If it is not, both an ice axe and crampons will be required, raising this into the realm of a technical ascent, not merely a scramble. In favourable years the steep, grey-black cliffs and gullies on the south side should be free of snow and ice by late July or August. Other years it may never dry off completely, and then it is best left to more technically oriented climbers.

Start at Chephren Lake trailhead at the southwest end of the Waterfowl Lakes campground on the Icefields Parkway, 57.4 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway junction and 19.7 km south of Saskatchewan Crossing. Drive through the campground to the west end and park near the footbridge across Mistaya River.

Follow the Chephren Lake hiking trail to the lake in about an hour and muddle along the left shore through forest and across rockslides. Barring moose or bear encounters, which stymied one group (!), you should reach the second inlet stream at the west end in another hour or so. Slower parties will choose to camp by this silty stream and make it a more leisurely two-day affair. If you are fit and moving steadily, one day will suffice, but if so, you should gulp as much water as possible at the clear, bubbling spring along the trail close to the back of the lake. Any water beyond here is likely to be silty or non-existent, and the elevation gain has yet to start.

Either hike along the right side or gain the awkward, steep crest of the lateral moraine leading toward the Chephren–White Pyramid col. Walk along this just a short distance to grassy, south-facing slopes – tasty little blueberries here – and head right to follow a watercourse up the open hillside. If water is flowing here, the ascent will probably require crampons higher up. This drainage splits farther up and the left branch leads toward an obvious scar breaking the lowest cliff band. The easiest places to get through this band are either here or some 75–100 m farther left: the greenish rock is steep but solid. As you go, remember to look back down so you will recognize the terrain on your return. It will look different from above – steeper, that is! You may see a fixed rope dangling here; easier terrain lies to the left of this.

The second wall is a black band about 20 m high. Traverse left on scree below it for 100 m or so and ascend an easy gully of light-brown rock. Contour farther left again over a rounded scree shoulder until the Chephren–White Pyramid col is visible. You now have a choice of routes. Either skirt northwest along the foot of a short cliff (toward the col) and plod summit-ward from that point, or you can angle up more directly to the top over snow patches and rock steps. En route a little chute cuts through a steep wall. Wearisome loose rubble leads to the summit ridge, and a short walk ends at a cairn and register. Despite myriad peaks to admire, it is likely the return trip, which is the same way, will curtail your available visiting time.

Major peaks visible on a clear day include Mount Columbia – the second-highest summit in the Rockies – as well as mighty Mount Forbes, all five Lyell peaks and the Goodsir Towers. Even the Howser Towers in the Purcell Range, 75 km away, are evident. Most awe-inspiring is the scene just left of adjacent White Pyramid: a multitude of glaciated summits awash in a sea of ice that is collectively known as the Freshfields.

Chephren (KEF-ren) was the builder of the second of the great pyramids of Egypt. The peak was once known as Pyramid Mountain but was renamed in 1918 owing to one already so named above Jasper.

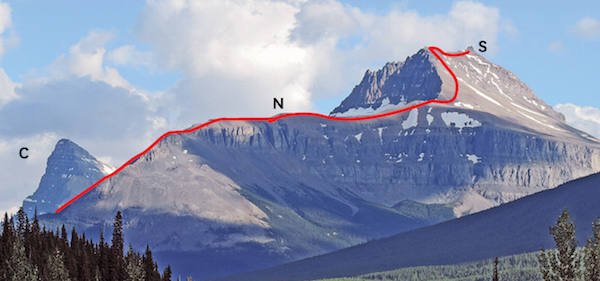

The Mount Chephren scramble route from the unnamed bump south of the peak. From the back of the lake, the route ascends moraine to south slopes and through rock bands.

Close view of rock bands and scramble route on upper Mount Chephren.

Difficulty: Difficult scrambling along the exposed and loose summit ridge

Round-trip time: 10–13 hours

Height gain: 1630 m

Maps: 82 N/15 Mistaya Lake; Gem Trek Bow Lake

Mount Sarbach, along with Kaufmann Peaks and Epaulette Mountain, forms part of a vertical escarpment rising 1600 m above the Icefields Parkway near Saskatchewan Crossing. Each supports large hanging glaciers below sheer east faces. Of the three summits, only Mount Sarbach is a scramble, and even then only when free of snow and ice. In cool, wet summers these conditions may not occur at all. This is a high mountain with a whopping amount of elevation gain and challenging scrambling making it best suited to capable, experienced parties. Its location guarantees a superb view, and a good trail facilitates the approach. As with any big peak, take an ice axe; even crampons may be needed. Try from August on.

Park at the Howse Pass–Mistaya Canyon trailhead on the west side of the Icefields Parkway (Highway 93), 5.2 km south of Saskatchewan Crossing and some 73 km north of the Trans-Canada Highway.

Follow the trail as it descends to Mistaya Canyon. This deep gorge is an impressive attraction and worth a moment’s pause. Cross the bridge and turn right, going uphill to a junction. Take the left fork for Sarbach. The trail rises gradually through forest and in 5 km reaches an old fire lookout site, now a flowery alpine meadow overlooking the Icefields Parkway. This is a logical snack stop, as elevation gain to the summit is still 1100 m.

Follow a trail directly back into the woods and grovel upslope to treeline and the north ridge. Immediately, the panorama wows you, revealing shimmering Glacier Lake and the Lyell Icefield. You might almost forget what the objective is! The first section of ridge is broad and easy save for two notches. The first is insignificant, but the second requires a 10 m descent in a chimney. Many parties find this notch to be the crux, rather than the final summit ridge.

Climb out of the notch and trudge up much debris. The ridge curves right, leading to a football-field-sized plateau, then steepens as it rises toward the false summit. Scramble up short cliff bands, choosing the easiest line. Much of the rock is loose, so use caution. Gullies around to the right may be useful or may be icy, while the ridge itself may be dry. I found it best to stay close to the crest. Higher up, you get a glimpse of the true summit, looking rather like a knob on flat ridge off in the distance. You could probably traverse hillside on rubble and bypass the false peak, but if cairn size is any indication, most parties stop at this lower spot.

About the point where you’re ready to cruise the final distance to the cairn, the anticipated summit ridge appears. It is a hodgepodge of loose blocks stacked horizontally with unforgiving exposure on either side. Some parties stop here. I felt these last 15 m were the crux and previously suggested a rope, but it seems many parties do not agree. Whatever the case, expect the worst and you should be pleasantly surprised. Thankfully, the summit is level and spacious. You can nestle in and savour one of the finest Rockies vistas you’re likely to set eyes on. The scenery west of Howse River to the Freshfield Group is stunning, as are the Lyell Peaks and nearby mounts Forbes and Wilson. On a clear day, you can see as far south as Mount Hungabee at Lake O’Hara. You’ll be glad you brought a camera.

Return the same way. You should remember to stay near the ridge crest on descent and not be lured into easier-looking gullies angling down to your left. Near treeline at the north end of the ridge, head for the small meadow to find the hiking trail again.

Peter Sarbach was a famous Swiss guide who accompanied J. Norman Collie’s expedition to the Rockies in 1897. While here, he led some notable first ascents, including Lefroy, Victoria and this mountain.

North end of Mount Sarbach from the Icefields Parkway. C: Chephren; N: notch; S: first summit.

Difficulty: Difficult and exposed summit ridge

Round-trip time: 8–12 hours

Height gain: 1700 m

Map: 83 C/2 Cline River

Ascending Mount Coleman gives a definite feeling of remoteness and reveals many normally unseen big peaks. The summit sits high above the east side of the Icefields Parkway and is visible from the road at about 3 km and 1.6 km south of the trailhead. Elevation gain is substantial and the ascent makes for a long, tiring day despite the excellent approach trail. A backcountry campsite at nearby Sunset Pass is ideal for an overnight trip. This outing is for experienced scramblers, as the final, narrow ridge abuts a steep ice face. Try from about mid-July on, when the summit ridge should be snow-free. Carry an ice axe.

Drive to the Sunset Pass–Pinto Lake trailhead on the east side of the Icefields Parkway, 16.7 km north of Saskatchewan Crossing.

Hike up the well-graded path to Sunset Pass. Minutes before the pass you get a first glimpse of the objective to the north, including the ascent route. At Sunset Pass the trail angles to the right toward a stream and campsite before continuing east toward Pinto Lake. To climb Mount Coleman, you first need to gain the big gully separating the southwest face of the peak from the rocky ridge just west of it. Then you hike to the high col between. If you walk farther along Sunset Pass trail, it should be obvious when to head north (left). Cross marshy flats and trees to reach this gully, but don’t expect a real trail; use your intuition.

The wide gully leads easily to the col, with rubble underfoot occasionally revealing brachiopods and other small fossils. The col (048735) provides a respite and a chance to survey both the unfolding panorama and the final 300 m or so remaining. A shallow gully leads directly to the crux: the summit ridge.

Once on the ridge, the summit lies south. A steep glacier abuts this narrow ridge, so be cautious as you make your way along it. After you descend a minor dip in the ridge, the less-exposed option follows the path of least resistance around to the right across slabs, then up to the cairn.

From the top at least 20 of the Rockies peaks above 3353 m (11,000 ft.) are visible. Some, like Mount Alexandra at the head of the wide river valley lying west, are so remote that they see few ascents even today. A plethora of towering peaks, glistening glaciers and green valleys surrounds you, and if the weather is clear, what more could you ask for? Perhaps a safe return, via the same route.

Professor A.P. Coleman and his brother Lucius did much exploring in the Rockies before the turn of the century. Three summers were spent in search of legendary Rockies giants Mount Hooker and Mount Brown, reputed to be some “17,000” feet high. Celebrations were appropriately scaled down when the long-sought-after peaks measured some 7,000 feet less than expected.

An approach view of Mount Coleman. C: col; G: gully; SG: shallow gully.

A picture-perfect summit view of mounts B: Bryce; S: Saskatchewan; and C: Columbia.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling, much scree and perhaps snow slopes via southwest side to north ridge

Round-trip time: 4–8 hours

Height gain: 1175 m

Map: 83 C/3 Columbia Icefield; Gem Trek Columbia Icefield

Most parties overlook Nigel Peak in favour of loftier, neck-craning mountains nearby, but for a non-technical ascent these summit views rival those granted by the glaciated, but less easily attained, giants on the Columbia Icefield. When clouds cloak mounts Athabasca and Andromeda, climbers too can probably salvage the day with this ascent. Try from July on; ice axe suggested

Park at the entrance to the Wilcox campground on the Icefields Parkway, 2.7 km south of the Columbia Icefield Centre. The trail to Wilcox Pass starts here.

Follow the Wilcox Pass trail for about five minutes to an opening in the forest and hike up the steep hillside toward Nigel Peak. Cross undulating meadows toward scree slopes on the southwest side of a subsidiary ridge trending northwest from 878868. Stay left of the stream draining the summit mass that flows down through Wilcox campground. Occasionally, waterworn slabs give you a temporary respite from the tedious scree underfoot and are particularly welcome where the terrain steepens near the ridge.

From the ridge, a rounded saddle connects to the main mass of the peak. Trudge up this – possible cornice on the right – detouring left at rotten rock steps. Some years, snow lingers right into August on this shaded slope. As you must either traverse across or above it to reach the north ridge, an ice axe is invaluable. It is a considerable distance down to the tiny snowfield below.

Although there have been ascents straight up the northwest bowl, rocks are often damp, while ledges hide under precarious piles of stones. Traverse farther left to the north ridge for a safer ascent. It is not necessary to tread on the minor glacier clinging to the left side of this ridge, but if the ridge is snow-covered you should avoid wandering left of the crest.

This strategic viewpoint from the top reveals at least 22 of the Rockies’ 50-odd 3353 m (11,000 ft.) peaks. Attempting to identify each should provoke discussion if not outright debate. Mount Robson qualifies as the farthest one (165 km), but Mount Bryce, although clearly seen from adjacent Mount Wilcox, is hidden behind Mount Andromeda from here.

Parties also sometimes reach the north ridge route by hiking along Wilcox Pass, then going around the north end of the rock “wing” and up the northwest slopes. This is a less steep but much more circuitous approach, and unless it is snow-covered, it does little to eliminate the ever-present scree. Return the same way you came up. The shaley basin around the creek flowing to Wilcox campground is a poor descent, as the banks are steep, hard dirt or gravelly slabs – unpleasant at best.

The guide Nigel Vavasour accompanied climbers and explorers J. Norman Collie and Hugh Stutfield during their explorations of 1897. On this historic trip they ascended Athabasca, gazed west and discovered the now-famous Columbia Icefield.

Telephoto of Nigel Peak from the snowcoach road. B: northwest bowl; N: north ridge.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling via southeast ridge, mild exposure near the top

Round-trip time: 3.5–6 hours depending on starting point

Height gain: 900 m

Maps: 83 C/3 Columbia Icefield; Gem Trek Columbia Icefield

Mount Wilcox pales in elevation compared to its neighbours Athabasca, Andromeda and Kitchener, but its strategic location and straightforward route makes it far more accessible to the average hiker or scrambler. When the weather co-operates, Mount Wilcox offers possibly the best view in the entire Rockies for the energy expended. On a clear day the panorama simply can’t be beat. Try from July on.

Begin either directly behind the Icefields Centre or at the Wilcox campground and the Wilcox Pass trail, 2.7 km south.

The most direct approach lies immediately behind the Icefields Information Centre. Faint trails lead to a somewhat obvious gully through the rock band above, although you can also find many other places to the right to ascend. Rubbly slopes ease to the rolling alpine terrain of Wilcox Pass, often the haunt of bighorn sheep. You can also reach this point via the Wilcox Pass hiking trail, although it is slightly longer. From the broad expanse of the pass, hike over to the southeast ridge and along a well-worn path that travels just below the crest. The view is magnificent. Only short sections require any hands-on scrambling, but toward the top expect a few mildly exposed spots. If, at some point, you find yourself looking clear down to the road on your left while confronted by a steep wall, you are probably off route. Backtrack and go around to the right instead. In general, keep right at any narrow bits and detour around steep snow patches that linger.

From the top you could spend considerable time with map and compass attempting to identify surrounding peaks. The icy giant between Mount Andromeda and Snow Dome is Mount Bryce, a highly prized but seldom climbed 3353 m (11,000 ft.) peak. North Twin, Twins Tower and mounts Woolley and Diadem are just a few of the other major peaks you can see from here. Nearby Nigel Peak may be on your “to do” list, and most of the scramble route up it is visible as well. Once you reach sensory overload, return the same way.

Yale scholar Walter Wilcox explored the Lake Louise area about 1893 with fellow students Samuel Allen and Lewis Frissell. His book Camping in the Canadian Rockies was an instant hit. Wilcox Peak was named by the renowned British alpinist John Norman Collie, whose explorations in the Rockies from 1897 to 1911 added considerably to the scarce information then available about this fabulous region.

Approaching Mount Wilcox from Wilcox Pass. The route ascends the left skyline ridge. PHOTO: BOB SPIRKO

Difficulty: Easy, mostly a hike

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 1100 m

Maps: 83 C/6 Sunwapta; Gem Trek Columbia Icefields

Tangle Ridge is another summit ideally located for photographing awe-inspiring peaks of the Columbia Icefield region. From the top you can see major summits not visible from either Nigel or Wilcox. Tangle also offers a long, easy ridgewalk with a loop back on the Wilcox Pass trail. Despite lack of a path partway through the intervening forest, reaching the top is straightforward. Morning light is preferable for photos. Try from late June on.

Park at Tangle Falls, 7 km north of the Columbia Icefield Centre on the Icefields Parkway.

To the right (south) of Tangle Falls is the signed trail for Wilcox Pass. Follow this for about 30 minutes, which should get you close to both the creek and a streambed on the opposite side. Watch for cairns. Cross the creek and head up through forest along the side of this often dry drainage. The left side leads more directly to the summit.

Continue up through forest to treeline onto patches of meadow, then good scree to the top. Behind you, familiar outlines of Athabasca and Andromeda loom. To your left, glaciated Kitchener and Stutfield are overshadowed by mighty Mount Columbia, second-highest in the Rockies. To the southeast, Nigel Peak displays a distinctive horn shape, while farther beyond, the many towers of Mount Murchison stand tall. On a clear day the panorama is breathtaking – even the solar-powered repeater on top doesn’t spoil the majesty. One note of caution: be wary of the glacier that abuts the ridge on the north side.

You can either return the same way or, for variety, hike along the ridge toward Nigel Peak, then descend scree slopes to the open environs of Wilcox Pass. The well-used hiking trail leads back to Tangle Falls and the starting point.

“Tangle” refers to difficulties encountered by an early party as they exited Wilcox Pass by this creek. Before the Icefields Parkway opened in 1940, Wilcox Pass was the normal travel route here. This was not because of Athabasca Glacier, but because of the Sunwapta River’s canyon.

Roadside view of Tangle Peak’s upper slopes.

Difficulty: Easy scrambling via southwest slopes

Round-trip time: 6–10 hours

Height gain: 1750 m

Maps: 83 C/6 Sunwapta Peak; Gem Trek Columbia Icefields

Sunwapta Peak is deceiving, as it is higher and takes significantly longer than what the highway view suggests. Besides an ice axe for snow lingering on the upper slopes, you’ll need nothing special except perseverance. On a clear day, the view of major peaks is terrific. Try from late June on.

Drive 15.6 km north of the Columbia Icefield turnoff (2 km south of Beauty Creek Hostel) to the Stanley Falls hiking trail sign. Park at a pull-off area on the east side of the Icefields Parkway. There is a less foreshortened view of the mountain about 2 km south.

From the pull-off, the trail curves over into the trees to a paved section of old highway. Do not follow the trail south to Stanley Falls; instead walk two minutes north (left) to a gravel outwash with cairn and flagging. As seen from the highway, this watercourse is the more southerly of two parallel drainages on Sunwapta’s slopes.

Hike up the left side of the drainage. Despite some deadfall, you should find a recognizable trail to treeline. Then angle right toward the ridge, trudging up long and often snowy slopes of rubble. Although appearing inconsequential from the road, this upper part now seems unending. And no wonder: just this above-treeline stretch alone entails 1000 vertical metres of height gain! However, the route is largely a walk, and as you toil along you may be interested (and possibly discouraged) to know that Steve Tober made an ascent in less than 2.5 hours in 1998. Feeling even more sluggish now? A periodic glance west toward mounts Woolley, Diadem and Alberta may help. On top, beware of a possible cornice on the east side. Return the same way.

During his exploits at the turn of the century, Professor A.P. Coleman used this Stoney Indian word meaning “turbulent water,” referring to the fast-moving nearby river.

An evening view of Sunwapta Peak from across Sunwapta River. The trail follows above the left side of the drainage. Notice the distance from treeline to the summit.