Indian Ridge 2720 m easy

Pyramid Mountain 2763 m easy

Hawk Mountain 2553 m difficult

Cinquefoil Mountain 2260 m easy

Roche Miette 2316 m moderate

Utopia Mountain 2564 m difficult

Roche à Perdrix 2135 m moderate

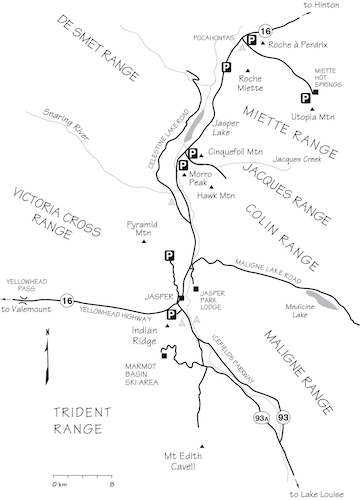

This section covers the Jasper townsite and the area east of Jasper along the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16). Most of this is dry Front Range country, and both topography and climate are not unlike Kananaskis and Banff. Peaks are comprised of steeply dipping limestone, and slabby west faces offer technical climbing routes, while ridges and east-facing gullies often provide feasible scrambles. During periods of bad weather along the parkway, a drive east of the Jasper townsite may save your day – rather like heading for Kananaskis when Lake Louise socks in.

Access The region is reached via Highway 93, the Icefields Parkway, which intersects the Trans-Canada Highway 2 km west of Lake Louise, then travels northwest for 245 km to Jasper. Meeting it at Saskatchewan Crossing is Highway 11, the David Thompson Highway, which runs east to Red Deer. Highway 16, the Yellowhead, joins Edmonton and Prince George, BC, via Jasper. As for transportation, Brewster operates a daily shuttle from Calgary to Jasper; Via Rail trains from Edmonton and Prince George stop in Jasper, as do Greyhound bus routes. Having your own vehicle is really the only practical way to get around, though.

Facilities Jasper has almost anything you will need. Totem Men’s Wear and Ski Shop both sells and rents equipment. Weather and other information is available at the Parks Information Centre on the main street. For a more relaxed outing, a gondola whips you up to the Whistlers, where an easy scramble of Indian Ridge begins. Near the park’s east entrance, you can get mellow (and clean!) in Miette Hot Springs, which is also near a few good scrambles. Gas, snacks and limited facilities are found at Pocahontas, 44 km east of Jasper on Highway 16, the turnoff for the hot springs.

Accommodation Lodges, cabins and chalets along the parkway are typically expensive and booked up. Jasper has a range of hotels and motels. For the budget traveller, campgrounds and hostels can be found along the way and around Jasper. All are popular in summer and fill up fast. A few kilometres south of Jasper, Wapiti and Whistlers campgrounds offer public showers. Located east of Jasper are Snaring River and Pocahontas campgrounds.

Information A rustic building on the north side of Connaught Drive (the main street, across from the train station) houses the Parks Information Centre. Finding it should be easy, as it is about the only green space on the entire strip. Staff are helpful and enthusiastic about local ascents and current conditions.

780-852-6176

Warden offices are just east of Jasper toward Maligne Lake.

911 or 1-888-WARDENS

Difficulty: Mostly an off-trail hike to summit; easy scrambling if traversed

Round-trip time: 4–6 hours from top of Whistlers tram; 5–7 hours to traverse

Height gain: 660 m; loss 180 m Add 960 m and several hours if you do not ride the tram.

Maps: 83 D/16 Jasper; Gem Trek Jasper and Maligne Lake

Close to the Jasper townsite, Indian Ridge is an easy, scenic jaunt that benefits from the popular Whistlers tram. From the upper tram station, the entire trip rambles above treeline, granting an expansive view of peaks and lakes. Whether you traverse it or simply hike to the highest point, it’s worth buying a lift ticket. For purists considering hiking up to the Whistlers rather than riding the tram, there are NO free rides back down. Try this trip from mid-June on.

Follow the Whistlers access road that leaves the Icefields Parkway (Highway 93), 1.7 km south of the Jasper townsite. Drive some 3 km to the lower tram station.

From the upper tram station, join the droves of puffing tourists hiking to the open plateau called Whistlers summit. As you tramp up, you’ll notice the massive quartzite boulders. These “erratics” were transported from nearby mountains during the last glacial advance but now sit far from any sign of permanent ice. Similarly, glacial erratics also rest on Mount Hawk, Roche Miette and other peaks east of Jasper. From the Whistlers, Indian Ridge sits some 2.5 km to the southwest across rolling alpine tundra. It is a pleasant hike to reach it, and there are paths along its rounded shaley crest that lead to the highest point. Only for the last few metres will you actually have to use a handhold or two.

Ice-clad Mount Edith Cavell is the commanding peak to the south, while the white cone of Mount Robson, the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies, towers in the distance to the northwest. Jasper’s many lakes dot the valley like puddles of ink spilled on a carpet of olive. One can enjoy much pleasant wandering here and that includes most of Indian Ridge. The far (northwest) end of this ridge has a couple of interruptions requiring brief detours and a short scramble off the ridge crest on the left (west) side. The rest is easy. Bypass the last part on the right, then walk down shale slopes to the stream between Indian Ridge and the Whistlers. Finally, regain 260 m back up to Whistlers and rejoin the masses again. Welcome back to reality.

Indian Ridge is next to Indian Pass, but whether the pass was ever used much is questionable. Whistlers, more commonly known as marmots, are true sun worshippers and often bask on warm rocks in alpine areas, oblivious to the aging effect of UV rays. Their loud, sharp whistle is not a sign of admiration for you – no, in fact they find your appearance alarming!

Indian Ridge from the Whistlers, showing traverse loop.

Difficulty: Easy scrambling

Round-trip time: A full day

Height gain: 1585 m

Maps: 83 D/16 Jasper; Gem Trek Jasper National Park

Pyramid Mountain, guardian of the Jasper townsite, is one of the better scrambles near town if you have a mountain bike. The 12 km access road is drudgery without one, but you can rent one locally. Clambering over big quartzite blocks delivers far-reaching views. Try from late June on.

Pine Avenue, which becomes Pyramid Lake Drive, intersects Connaught Drive (the main street) near the west edge of town. Follow it for 7 km, passing Pyramid Lake and park at the locked access gate.

From the parking area, the gravel road rises gradually at first through montane forest, seemingly indifferent to the peak’s location. Instead it meanders well east of it. Cyclists will welcome the occasional small streams, especially on the big hill that leaves everyone puffing, and perhaps pushing too! At 8 km you pass by a rougher road branching rightward to the Palisades. Eventually the road flattens somewhat and crosses a final stream, and you now see the peak with the microwave service tram strung up its east face. Without the tram and road, the lovely subalpine setting here would be a truly aesthetic start to the ascent.

The normal route up is via the north ridge, the one on your right. It is straightforward to simply tramp up open slopes nearby to reach it. Once you gain the crest, Snaring River valley is your companion to the north, while the mighty Athabasca River meanders its way east.

The ridge rises in steps, and you scramble up, over and around big, lichen-clad quartzite blocks. The way is obvious. Mount Robson, draped in white, dwarfs every other peak in sight, which isn’t exactly a revelation. It is, after all, the Canadian Rockies’ highest summit. To the south, Tonquin Valley Ramparts vie for attention too. After admiring the scenery long enough, you can decide on your descent route.

On return, either descend the same way or go down the southeast slope, circling back toward a small tarn below, and back to the approach road. On descent, this convex slope suggests cliffs below, but if you aim for the point where the ridge meets the slope, it should all work out. Contour to the right at any nasty gullies or the short rock band at the bottom and hike back to your bike. If cycling, the ride down is a good adrenaline rush and requires much braking. Be sure your brakes work well and stop to let them cool down when they get too hot to touch.

Apparently a strenuous multi-day trip is possible toward Elysium Pass from Pyramid Mountain, visiting peaks such as Cairngorm and mounts Kinross, and Henry. Park wardens may have information about this long trek.

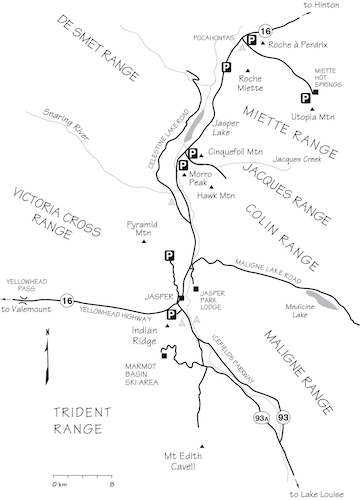

Pyramid Mountain route before the tram tower was removed. For variety, the left skyline can be descended.

Difficulty: Moderate via west face except for 5 m of difficult slab scrambling.

Round-trip time: 7–10 hours

Height gain: 1540 m

Map: 83 E/1 Snaring River; Gem Trek Jasper and Maligne Lake

Hawk Mountain, northeast of Jasper, is one of the most popular scrambles in the park and for good reason. It offers an easy approach, a short crux, a variety of interesting terrain and much less scree-slogging than usual. As you traverse high along an undulating spine of limestone, you are treated to fine, far-ranging views over the wide Athabasca Valley. Many peaks in the Colin Range consist of steep, slabby walls and exposed ridges and are beyond the realm of scramblers, but Hawk Mountain is a pleasant exception. Try from about mid-June on.

From Jasper, follow the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16) northeast toward Edmonton for 20 km. Park at a pull-off spot at the east end of the bridge over the Athabasca River.

From parking, go up a badly eroded dirt bank and head off to the right on a path often used by rock climbers practising at Morro slabs. This trail is part of the historic Overlanders Route taken by 150 hardy migrants in 1862 who left Ontario bound for the BC Interior.

There are two approaches in common use: Morro Creek left side and Morro Creek right side, for lack of better terms. The original, right side approach has a stretch of deadfall, as the lower slope is criss-crossed with old burnt lodgepole blowdown, but it isn’t really that bad. The left side is open and a wee bit shorter but requires wading the creek down in the canyon. In high water season the right-hand route may still be the better option –drier if nothing else.

Follow the approach trail for 20–25 minutes as it contours south above the valley floor. Note a section where the trail enters mossy forest and curves right with a small pond visible down to the right on the valley floor. Watch for a key marker here at a rocky outcrop at a bend: at head height is a metre-wide hole in the grassy wall on the left. This is just before you emerge from forest. Some 65 paces beyond this hole, just around the corner, follow a good trail diverging left uphill. It heads for the left-hand side of Morro Creek. When alongside the creek, watch for the spot where the trail cuts right and quickly descends to cross the creek. Grovel up the bank to meet the original trail on the right-hand side.

From the parking lot, go for 35–40 minutes and cross the gravelly outwash of Morro Creek. The right-hand sidetrail is flagged and stays close to the creek until a stretch of downed lodgepole forces you to go right. Either head back left to the canyon again or head uphill to intercept the main trail above. The two approach trails rejoin just below an overlook at the far left end below the first slabby wall. At this spot you will see a slot canyon and perhaps a waterfall, depending on water flow. Now a beaten path rises gently to the right, staying below brown slabs, to an open, shaley hillside overlooking the next drainage south of Morro Creek at 281750.

Hike straight up through a short belt of trees and rubble to a band of grey slabs cleft by a 3-m-high (awkward) chimney. Better to simply scramble up slabs to the right. Above the chimney the eroded trail climbs up dirt, then more slabs. Angle right and easily overcome these too. Continue up steep terrain on this obvious trail into forest. This is an important spot to find for your descent and may well be marked with way more cairns and flagging than is necessary. Then again, one more cairn can’t hurt. The section from the chimney to here is the crux, and now that you are on the very backbone of the mountain, it would take a concerted effort to get off route. Nobody has yet.

Wander through timber along the ridge and in 20 minutes emerge onto rough slabs sculpted by eons of wind-driven rain. The summit is visible now, but distant. When the ridge peters out, descend left and gain the next ridge over, where some nice scrambling follows. You are now on the main spine leading to the summit. Notice the many quartzite boulders scattered randomly along this limestone mass. They look out of place, and in fact they are. These “erratics” were transported by ancient glaciers from around the Mount Edith Cavell area. And where has the glacier gone now? Back for more rocks! As if that isn’t odd enough, at one time, parties saw the remains of a moose skeleton lying on the north ridge of Hawk Mountain. Although nobody knows what brought a gangly swamp-lover way up to goat paradise, the glacier can’t be blamed – it only brought rocks.

Most parties return the same way, watching for the all-important point for descending those west-face slabs. It is also feasible to traverse toward the Hawk–Colin col, descend south to 320730 and follow a treed ridge northwest back to the burned area and the second drainage south at 284750. While feasible, it is of no particular advantage.

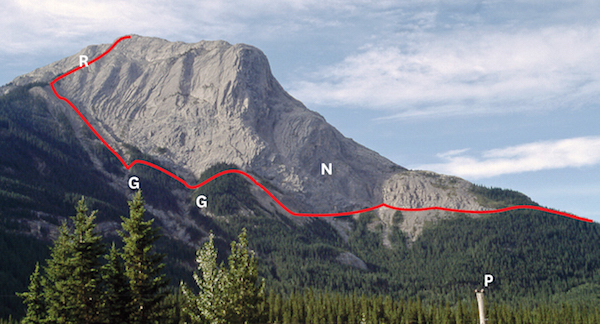

The Hawk Mountain ascent route viewed from Highway 16. C: crux chimney.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling for one section

Round-trip time: 5–7 hours

Height gain: 1200 m

Maps: 83 E/1 Snaring River; 83 F/4 Miette; Gem Trek Jasper–Maligne Lake

Cinquefoil Mountain is the first high point of a long, lazy ridge in the Jacques Range, east of the Jasper townsite. Readily accessible, it involves little actual scrambling and offers a straightforward way to get up high enough for an expansive view. All told, it is a pleasant outing and not likely to be crowded. Try from May on.

Drive to the Merlin Pass trailhead on the south side of the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16), 24 km east of Jasper and 20 km west of Pocahontas.

Originally my approach followed the Merlin Pass trail. At a small lake, go around to the left (for much of the season the water level here necessitates a bit of a bushwhack around it). When the brush and forest open up, head left toward green, open slopes of the peak. Watch for a trail. An optional, more direct way to these lower slopes starts 900 m farther east where the ridge is close to the highway. Cross a water-filled ditch wherever it’s narrowest, then bushwhack to either the ridge or the open slopes on the west side. In a straight line it is about 150 m through the trees to open slopes.

Once on the open slopes, the objective is clear: go up. Use whatever trails you encounter to link one clearing to the next. At a forested dip in the ridge you can angle leftward uphill into trees to avoid losing height. While paths through the woods are helpful, you can’t help but notice how much better suited they are to bodies that are less than a metre tall. Note to the Irish, however: these are unlikely to be the work of “the Little People.” Not unless they leave hoofprints, anyway.

A rocky outcrop higher up provides an opportunity to admire the unfolding panorama of Jasper and Talbot lakes below with square-ended Roche Miette rising behind. As well, you can study the last section to the summit, although it will be in shadow in early morning. Clumps of small firs huddled on isolated ledges give way to limestone ribs which avoid some of the adjacent rubble. Soon after, you realize that the summit is not one specific high point but rather a series of points along a broad, undulating ridge.

Hiking along this ridge is delightful. Underfoot, patches of moss campion anchor small plant communities, and there is much evidence of bighorn sheep – watch where you sit! When they aren’t serving as roadside attractions on the highway below, the sure-footed creatures use this mountain as a favourite getaway. Many have a high tolerance for cameras and will pose willingly.

Most parties will be happy to lounge around on Cinquefoil Mountain and then return the same way. Continuing south immediately involves steep rockclimbing followed by ever-increasing amounts of loose rubble. The farther you go, the less enjoyable it becomes. As you look northwest, it appears that Mount Greenock and Cinquefoil once formed a continuous upthrust ridge, now worn through by the Athabasca River.

Cinquefoil, or potentilla, is an alpine plant with five bright-yellow petals that grows here and on many other mountains.

Cinquefoil ascent route. H: Highway start; M: Merlin Pass trail start.

Difficulty: A moderate to difficult scramble via northeast face

Round-trip time: 3.5–7 hours

Height gain: 1310 m

Maps: 83 F/4 Miette; Gem Trek Jasper National Park

Roche Miette’s vertical walls have stirred emotions since bygone days when voyageurs plied the nearby Athabasca River. While the towering west face is dramatic, the back side is tame, offering a much easier ascent. This scramble is one of the more frequented outings in the region, and as a result there is a beaten path that also serves as the climbers’ descent route. Try from about June on.

Follow the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16) northeast from the Jasper townsite toward Edmonton for 40 km, or 3.5 km southwest of Pocahontas, to a gravel access road on the south side of the highway. Park at the locked gate alongside the highway.

Walk through the clearing, angling right, and notice a rectangular, sunken, concrete-block structure and metal cover which protects a buried pipeline control valve. Go sharply left here –parallel to a gravel diversion dike – and follow an old road heading northeast that aims a bit left of the peak. DO NOT TURN RIGHT TOO SOON as many folks do. The first sidetrail goes toward the north face and is not for the scramble route. Instead walk a full 10 minutes at a brisk pace to where the road reaches the top of a slight rise. There is an obvious, well-beaten, cairned and flagged trail diverging right. It enters tall evergreen trees and vegetated forest as it heads toward the peak. The old road you followed shows much less use beyond this point, which by GPS measures 1.1 km from the start. You soon cross the more easterly of two drainages descending from the north end of Roche Miette. The path ascends hastily and is well travelled. Go right at the first intersection, left at the next one. In about an hour reach open slopes of a ridge, the second ridge to the east as seen on approach. Here, the Athabasca River can be seen winding eastward past Disaster Point. The high point of this ridge offers a delightful panorama and a good place to eyeball the rest of the route. A faint trail angles left from the connecting saddle to a gully cleaving the first cliff band. Successive bands are similarly short. Most are easily overcome by traversing left to convenient gullies that allow you to ascend these obstacles with minimal fuss and only moderate scrambling. A more exciting, but exposed, option is to angle left onto clean slabs for the finish.

The top of Roche Miette is a broad, undulating plateau sprouting tiny mosses, hardy alpine flowers and scattered patches of grass that nourish local bighorn sheep. The summit awaits 15 minutes southeast past a small hump. For those with time and energy to waste, you can also ascend two slightly higher points lying south from the separating col. These involve only a bit of steep scrambling but are not really worth it. The west one is especially rotten and may have collapsed in a strong breeze by now.

The summit block of Roche Miette is made entirely of a particularly erosion-resistant limestone called Palliser Formation, a rock type that composes the steepest cliffs of many peaks throughout the Canadian Rockies. You may also notice the odd lichen-clad quartzite boulder resting innocuously here and there. As on Mount Hawk, which is closer to the Jasper townsite, these glacially transported specimens originated farther west in the Main Ranges, close to quartzite peaks like Edith Cavell and the Ramparts. When the glaciers retreated, these erratics were left high and dry, sometimes on limestone summits like this one.

Roche is a French word meaning “rock.” Miette was a legendary French Canadian voyageur who apparently had enviable qualities for tolerating the hardships of travel. It is said he could play the fiddle and tell yarns with the best of them, too. When taunted by comrades about climbing this mountain, he responded to the dare by doing just that, dangling his legs over the precipice while contentedly puffing his pipe – or so the story goes.

Morning sun lights up the ascent slopes on Roche Miette. R: ridge; S: saddle; F: first cliff band.

Difficulty: Difficult for short section; exposure

Round-trip time: 7–10 hours

Height gain: 1160 m

Maps: 83 F/4 Miette; Gem Trek Jasper–Maligne Lake

Utopia Mountain may not be complete paradise but it is an interesting scramble. It has seen comparatively few ascents in the past. Located in the dry Front Ranges near the eastern boundary of Jasper Park, its biggest asset may be the starting point at Miette Hot Springs. What could be a better way to end a scramble than a well-earned soak in the steaming sulphur pools? The view from the summit includes prairies, gentle ridgewalks and smaller peaks nearby, plus distant giants like mounts Robson and Edith Cavell. As part of the approach follows a streambed, the trip is better when the creek is not too high. Although the mountain would certainly be feasible earlier, I would suggest trying from about mid-July on, because of spring runoff.

Follow the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16) northeast from the Jasper townsite toward Edmonton for 44 km to Pocahontas, then turn right and go southeast 18 km to the road’s end at Miette Hot Springs. Park in the lot near the picnic area at the far (south) end. Note: Utopia Mountain can be seen from the road about 1 km before reaching the hot springs. The peak sports a wide band of brown shale partway up north-facing slopes. The skyline ridge is the ascent route.

Find a trailhead and map at the south end of the parking lot. A paved pathway descends to Sulphur Creek, passing the old aquacourt and interpretive signs, including a small natural hot spring. Continue on the trail to where the stream forks, about 20 minutes away. Leave the trail and follow the right-hand branch of the stream, which drains the northwest slopes of Utopia Mountain. A trail with cairns and flagging is found on the left (east) side of the creek. After about 20 to 30 minutes, watch for a steep animal trail heading left up the hillside. This trail is well trodden by sheep and starts right before a large washout of the hillside. Head up this steep path to treeline, perhaps noting where it emerges to simplify finding it on the return.

Continue up the open, meadowy slope and look for low-angled terrain on the rocky ridge to the right. Scramble up and gain the crest. Follow this ridge up alongside a gully of brown shale, crossing it near the top and continuing up rubble to another ridge above. This second ridge is separated from the mountain by a wide gully of grey scree descending right to treeline. The ridge provides interesting scrambling, particularly where it steepens for a short distance higher up. A couple of spots present brief exposure. Near the top of this ridge, work around right to avoid overhanging rock and gain the top of the wide scree gully adjacent. The flat plateau at the top makes a fine place for a timely rest, a snack and a chance to enjoy the much improved view.

Again the route ascends a slope of rubble on the right, this time to the summit ridge. The snowy, cone-shaped summit of Mount Robson is visible to the west on a clear day. Continue along this ridge to the false summit, marked by two survey markers set in the rock and an old wooden tripod. After much ado, finally the real summit is just minutes away.

From the top, the landscape presents many contrasts. Far to the west rise high peaks like Mount Edith Cavell and Tonquin Valley Ramparts, while to the east are gentle, eroded ridges along the park boundary whose tops would afford fine, long rambles. The prairie spreads out beyond. To the north, Ashlar Ridge displays its clean-cut, slabby face of Palliser limestone. The mighty Athabasca River meanders off in the distance.

The register shows that several parties have reached the summit via Utopia Lake to the south. This would not be a likely direction to descend, because of the extra return mileage incurred. We returned the same way, with one small diversion. Rather than downclimb the steepest parts of the upper ridge, it is possible to descend the wide grey-scree gully until feasible to traverse to the right and regain the ridge. Then retrace your ascent route. Continuing all the way down the wide scree gully also is an option. Move left at slabs near treeline and descend to the upper valley. This would add more travel alongside the creek, probably boulder-hopping and without benefit of a trail.

Holmgren & Holmgren’s Over 2000 Place Names of Alberta reveals that for the surveyors, Utopia was an escape from the flies. Utopia is also when you slip into the relaxing hot pool at the end of a successful day.

The crux section on Utopia Mountain is not overly demanding but does add interest to the ascent. PHOTO: DINAH KRUZE

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling, some exposure near top

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 1000 m

Maps: 83 F/4 Miette; Gem Trek Jasper National Park

Although this small peak is often ascended via technical climbing routes on its west and north aspects, the normal descent also makes for a quick way up. Close to the road and right on Jasper Park’s eastern boundary, like nearby Roche Miette, it grants a respectable view and is quite straightforward. Try from mid-June on.

Jasper Park’s east gate is approximately 50 km east of Jasper on the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16). Turn south off the highway 800 m east of the park gate onto an unmarked road that leads to a rock cut at the end of the north ridge, about 50 m from the road. Park here.

At the right edge of the rock cut are many sheep trails heading onto the open north ridge of the mountain. This ridge lies exactly on the park boundary. In an hour you pass two brief rock outcrops in quick succession. Stop just past these. Do NOT continue to a third and higher rock bluff or you’ll have to backtrack. Instead, contour left through trees until a faint trail appears along the base of slabs on the east side of the ridge. Now the route begins to work around to the east side of the mountain.

Follow this path toward the north face as it hugs the base of vertical limestone walls. It then angles left and rises up a steep shale slope by a small drainage. Still rising rapidly below the northeast face, you soon reach a major watercourse. It is deeply eroded and recognizable by U-shaped folds of rock. A cairn reminds you to cross the drainage and gain the rib separating this major drainage from the next one over. Hike up this steep dividing rib on a good trail through trees, then turn left across a second gully when the trees end. The way is obvious. If you have not brought ski poles or an ice axe, you may wish you had now; this shale slope is loose and tedious. Continue straight up the hillside until it levels off on a minor northeast-trending ridge (467963), a good place to reap the scenic rewards of your toil thus far.

It is but a short, direct scramble to the top from here, whether on the crest or along either side. A stroll west soon leads to the summit cairn, and from here you can enjoy a panorama of peaks, boreal forest and the broad Athabasca River. This river served as a vital transportation link during the fur trading era. Bighorn sheep apparently favour this vista too: be careful not to sit in something.

If you haven’t yet had enough, it is also feasible to scramble south along the ridge. Attaining the first high point is no problem, but the second one requires a few metres of steep scrambling on the ridge crest. Either side of this steep step is much more exposed and loose. From there you’ll no doubt notice that it looks straightforward to continue toward Fiddle Peak too. The question is, how much is enough? Once you’ve discovered your limit, return via the same route.

The Holmgrens, in Over 2000 Place Names of Alberta, relate an apparent resemblance of rock foliations (seen from the highway east) to feathers of a partridge’s tail. “Perdrix” is French for partridge.

From the east, N: north face; R: northeast ridge; G: gullies; P: damn pole!