Mount Nestor 2975 m moderate

Mount Sparrowhawk 3121 m easy

Mount Buller 2805 m moderate

Mount Engadine 2970 m difficult

The Tower 3117 m moderate

Mount Galatea 3185 m difficult

The Fortress 3000 m easy

Mount Chester 3054 m moderate

Gusty Peak 3000 m easy

Mount Shark 2786 m moderate

The Fist 2630 m difficult

Mount Smuts 2938 m difficult

Commonwealth Peak 2775 m moderate

Mount Murray 3023 m moderate

Mount Burstall 2760 m difficult

Prairie Lookout 3185 m difficult

Mount French 3234 m difficult

Mount Jellicoe 3075 m easy

Mount Robertson 3194 m difficult

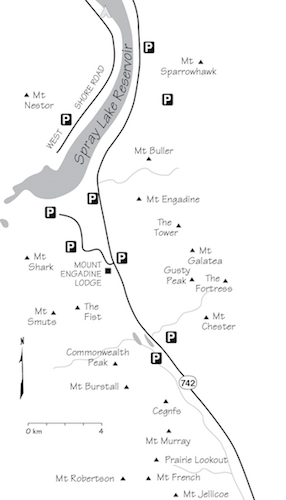

Peaks in this chapter form a mountain corridor accessed via Spray Lakes Road and Smith-Dorrien Trail in Kananaskis Country. This area lies south of Canmore and north of Kananaskis Lakes and is reached from either end via the 60 km gravel road paralleling Spray Lakes Reservoir.

In spite of the gravel road, this area is popular with hikers, climbers, fishers and mountain bikers. Mountain structure is typical Rockies Front Range – limestone bedded with a noticeable southwesterly dip. The corridor sits at a higher elevation than Kananaskis Valley, one range east. Precipitation here is greater and the scrambling season is a little shorter. If weather is inclement, either Kananaskis Valley or may well be drier than what you’ll find here. Owing to heavier snowfall, some peaks may not be in good (snow-free) scrambling condition until July. North-facing slopes may harbour snow until August. Mount Sir Douglas is the highest peak in the area, but it is not a scramble. The French–Haig Glacier area offers several scrambles that cover a wide range of difficulty.

As with much of the Rockies, rock here is typically downsloping, shattered and loose. Mount Smuts, although limestone too, boasts solid, steeply angled slabs and ribs. Since the first edition of this book, Mount Smuts seems to have become a testing ground for many scramblers. This airy ascent pushes the upper limit of what can realistically be called scrambling, but whether one uses a rope or not, it is an exciting outing. Register comments suggest that successful parties have enjoyed it; however, a fatality has occurred due to a fall from the summit. Other routes in this neck of the woods are easier and include plenty of scree.

Chester Lake, the most heavily visited spot, is a favourite day trip for hikers and offers a few good scrambles. Overuse has damaged lakeshore meadows and overnight camping is no longer allowed. This should not affect scramblers, as access is quick anyway. Despite periodic proposals, the Smith-Dorrien corridor remains free of the blight of commercial development, largely due to public pressure. One hopes it will not suffer the fate that has befallen the Canmore Corridor. Paving the road would hasten the ruin, as tour buses would follow in short order.

Access to the north end of Smith-Dorrien is best from Canmore via Spray Lakes Road, which starts after the Bow River bridge. For the south end of Smith-Dorrien, turn off Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40) at King Creek, 50 km from the Trans-Canada Highway, then turn right in a further 2.5 km. Chester Lake is almost an identical distance from Calgary from either Spray Lakes Road and Canmore or via Kananaskis Trail. The latter is quicker owing to more pavement and fewer bends.

Facilities and accommodation Fortunately, there are no hotels in the Smith-Dorrien corridor yet. Engadine Lodge, a small privately owned inn 37 km south of Canmore, offers rooms, meals and licensed mountain guide service. Otherwise, visit Canmore for a roof over your head (or a beer in your hand!). Boulton Creek near Kananaskis Lakes has a small store and cafe. Campgrounds are at Kananaskis Lakes and on the west side of Spray Reservoir across Three Sisters Dam, 18 km from Canmore. This rustic campground was once free, but this oversight has since been corrected by government money-grabbers.

Mount Engadine Lodge: 403-678-4080

Boulton Creek Trading Post: 403-591-7678

Kananaskis Country Campgrounds: 403-591-7226

Backcountry camping permits: 403-678-3136

Updated trail info: kananaskisblog.com.

Emergency The RCMP has a station at Elk Run Boulevard and Bow Valley Trail, just east of Canmore: 403-678-5519. In the event of a climbing-related accident, Kananaskis Country rangers would respond. There are no info centres or ranger stations anywhere along Spray Lakes Road or Smith-Dorrien Trail, only a pay phone located close to Three Sisters Dam, 18 km south of Canmore on Spray Lakes Road. Kananaskis Country emergency services can be reached at 403-591-7755. Emergency 911 service is also available through most of K-Country. Be sure to specify which area you are in.

Difficulty: Mostly a hike by south slopes; brief moderate scrambling at the top

Round-trip time: 6–8 hours

Height gain: 1250 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village, Banff–Assiniboine

Mount Nestor boasts an impressive view of the Spray Lakes vicinity and it is virtually impossible to lose your way on ascent. The east face sports a technical rock route and the south slopes are the normal descent. This south side is also a pleasant, no-fuss way to reach the summit and begins right next to West Shore Road. This road is typically closed to vehicles just past the campground, necessitating a bike approach for about 13 km. Try from late June on.

From the bridge over the Bow River in Canmore, drive Spray Lakes Road for 17.3 km and cross Three Sisters Dam to the West Shore access road. The closure is past this. Follow this winding gravel road for a further 13.4 km to where the road makes a quick S curve as it climbs a small hill. Mount Nestor’s south drainage is by the bend at the bottom of the hill – watch for flagging or a cairn.

At the base of the hill there should be an animal trail that follows along the right side of the overgrown drainage, just above thickets of willow and poplar. Within minutes, pass through these poplars and cross the drainage to follow up the left side until, some 20 or 30 minutes after starting, you’re out of the trees. To the south is an unrestricted view of mounts Birdwood, Smuts and Sir Douglas.

You have two other options for ascent. The usual way up is evident and next to impossible to lose, as you are following a wide, straight trough – a geologist would call it a syncline – caused by folding of rock layers. You hike past krummholz and bearberry to more rubble than is necessary. Where the trough widens at the top, cross over left to a broader gully and hike up onto a rounded shoulder to the skyline. Rather than completely ascend the trough, you can instead branch left and go up the big gully curving to the right. I used to suggest this for descent but people have found it less toilsome and better for ascending. The two routes meet higher up. Near the top, descend about 10 m and cross a brief connecting ridge to the main summit, about 2 m higher. For those intimidated by a first impression of this route, relax; it isn’t that bad. This and a brief bit of exposure just past this ridge are the only excitement of the day. Those who want a more challenging ascent can scramble up the skyline ridge to the right of the trough. Parties assure me it is a scramble.

The summit is not all that roomy. In fact it is quite small, but there are plenty of peaks to admire, like Sir Douglas, the Goodsirs and Ball. Mount Assiniboine, though, steals the show, to the west-southwest if you didn’t know.

Ships involved in the Battle of Jutland have lent their names to many Kananaskis peaks. Nestor was a destroyer in the battle until it was itself destroyed –or at least sunk, which amounts to the same thing.

Mount Nestor from Spray Road showing typical routes up and down. T: trough.

Difficulty: An easy scramble via the west slopes

Round-trip time: 6–10 hours

Height gain: 1415 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village, Banff–Assiniboine

Mount Sparrowhawk provides an expansive view of Spray Reservoir. Its west slopes are a giant heap of rubble, and you shouldn’t have any trouble ascending. The peak was once touted as the downhill ski venue for Calgary’s 1988 Winter Olympics, but nearby Mount Allan was chosen instead. The sole reminders now are a few discarded poles, snow-fencing and markers on the upper portion of the once-proposed runs. The ascent is worthwhile; plod up it from late June on.

On Smith-Dorrien–Spray Trail, drive to the Sparrowhawk day-use area, 26.3 km south of the Bow River bridge in Canmore.

Start across from the day use area (181442) where an obvious trail angles up the hillside. Sparrowhawk Creek is the stream just metres to the south and despite a trail there, that is NOT the correct drainage for Mount Sparrowhawk. Forbes Creek, the next one north is the right one. The trail will make a left, head north and then take you up onto Read’s Ridge above the Forbes Creek drainage. Before treeline you leave the ridge and drop down left into the upper part of the drainage. Here the steep wall of Read’s Ridge will be on your right, with the summit bump ahead on the horizon. Read’s Tower, the high point of the ridge, ends in an abrupt drop-off, and unless that is your ultimate destination you should be down beside it at treeline. This last bit of greenery is a good spot for a break and a snack, as you still have more than half the elevation to gain, despite appearances.

The route heads up rubble towards the notch at the end of Read’s Ridge and from there wanders up open slopes to the summit block. To dull the drudgery, it is worth occasionally looking behind you to savour the scene of Spray Lake and the panorama of innumerable Rockies peaks. At the summit the trail leads around the right-hand (south) side and ascends a more easterly slope of rubble, steepish in places, to the top. Ski poles will be appreciated. Most people return the same way.

Mount Sparrowhawk is not named after a bird as you might expect, but rather a First World War battleship – which in turn was probably named after the bird.

Mount Sparrowhawk’s west slope route stays below and on the north side of RT Read’s Tower, then circles to the right at summit cliffs. Despite the route’s being straightforward, at least one rescue has occurred here.

Difficulty: A moderate scramble if upper slabs are snow-free and dry; brief exposure

Round-trip time: 5–8 hours

Height gain: 1010 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village, Banff–Assiniboine

Mount Buller is readily accessible via a good hiking trail or an open gully. This Kananaskis peak is not likely to be crowded, and the view warrants at least one visit. A slab higher up adds interest. Try from about June on.

For the hiking trail approach, park at the Buller picnic area on the west side of Smith-Dorrien Trail–Spray Lakes Road, 35.4 km south of the Bow River bridge in Canmore and 32 km north of the Smith-Dorrien Trail–Kananaskis Lakes Trail junction.

The usual approach to Mount Buller is via Buller Pass hiking trail, but the high col could also be reached more directly from Spray Lakes Road by the obvious drainage 3.5 km north of the Buller picnic area. For the hiking trail approach, cross the road and follow Buller Pass trail for about 35–40 minutes until you come to a small, logged trailside clearing that offers a marginal view of Buller’s summit ridge and the col you must attain. This clearing will be just beyond trees blackened by a prescribed burn. If you miss this clearing you come to a small, bridged stream in about 4 minutes. The drainage from the high col is not a wide one, even after the record-setting rains of June 2013. Although not obvious, its position can be estimated by noting that to its left are steep, lush-green slopes, while to its right the upper slopes tend to be shaley or slabby grey rock. While the very lowest part of the drainage is too steep to scramble up, most of it above that is easy to ascend. From the clearing, bushwhack through the forest, aiming for the col. The 2013 rains brought debris from the drainage right down into the forest and even reached the small aforementioned creek just upstream of the bridge. If you encounter this debris you’re on route. Otherwise, stay on the steep, green slopes and move rightward to get into the drainage gully when feasible. An ice axe can be useful on these steep, vegetated slopes, especially if they are wet.

Once in or beside the drainage gully the ascent to the col is straightforward but relentlessly steep. A fatality occurred here in April one year when snowmelt caused rockfall. Gullies are natural funnels and should be avoided in such conditions. From the col (181385) between Buller and the unnamed point to the southwest you have 350 vertical metres left to go. There is an obvious trail but it is better for descent. Ski poles are definitely an asset on this unpleasant, ball-bearing rubble. Near the top, the peeling effect is evident at a short, narrow friction slab. You do not want to find snow here, as an airy drop exists on both sides and a slip would be fatal. This slab is the only interruption to the tedium of trudging.

Of all the western horizon peaks, the highest visible is Mount Assiniboine. To the left of it is the pointed peak of Mount Eon, a summit of some historical significance. It was first climbed by Dr. W.E. Stone, a distinguished alpinist of the day. He generally hired a mountain guide, but not this time. After ascending the summit chimney, he promptly plummeted back down it and was killed. His horrified wife could only watch as the tragedy unfolded. Several days later she was found and rescued by local guides and packers when the two failed to return.

You, though, must not fail to return, so use the same route you ascended.

Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Cecil Buller of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was killed in the Battle of Sanctuary Wood, 1916.

Mount Buller summit ridge as seen from trailside clearing. C: col; S: summit.

Telephoto view of the ascent route from Buller Creek approach. B: Buller Creek; C: col.

Difficulty: A difficult scramble via west-northwest ridge

Round-trip time: 7–10 hours

Height gain: 1170 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village, Banff–Assiniboine

Mount Engadine’s ascent route offers a variety of terrain, beginning with a steep bushwhack to treeline and a long ridge that becomes more challenging as you go. Detours around the hard parts of this northwest ridge are possible, but the route still offers enough hands-on scrambling to make it interesting. Note that there is no quick, easy way off. Try from late June on.

Drive to Buller picnic area on the west side of Smith-Dorrien–Spray Lakes Road in Kananaskis Country, 35.4 km south of the Bow River bridge in Canmore and 32 km north of the Smith-Dorrien–Kananaskis Lakes Trail junction.

Cross the road and hike Buller Pass trail for 15 minutes. Wade or hop Buller Creek and bushwhack for some 45+ minutes towards treeline and the ridge above. Walk along the base of west-facing slabs and scramble up rubbly gullies to the ridge.

If you stick to the ridge crest, the route is airy and exhilarating. Expect plenty of exposure in places and periodic detours to the right using rubble to circumvent various cliff bands and overhangs. The main challenge comes at a significant overhang close to the top which suggests a major loss of elevation is necessary. However, if you descend some 10 metres on slabs, you’ll find a weakness that will allow you to scramble down the (west) side of this overhang. Much of the route is good scrambling, but the final 200 m deteriorates into tedious, treadmill rubble. More solid footing is found to the right, where a bit of slabby rib projects above debris.

The summit view is spectacular, with Mount Assiniboine dominating row upon row of summits to the west. This impressive peak was first ascended in 1901, by Reverend James Outram and his guides.

Once in a while, parties descend the same way, but more scramblers head down the big west-facing gully after descending the west face for some distance. This gully is not entirely a cruise – a waterfall slab will need detouring and careful downclimbing. Some parties avoid it and traverse over to a somewhat easier adjacent gully to the right (north). You can reach this more directly by retracing your steps down the ascent ridge, staying below the crest until able to angle into this gully. You may find a flagged path in the forest if you’re lucky; otherwise expect deadfall somewhere along the way.

The Engadine is a world-renowned tourist mecca in the Swiss Alps, but this Rockies peak is named for a ship that played a part in the Battle of Jutland.

Mount Engadine ascent route and two possible descents. S: slabby step.

Difficulty: A moderate scramble by south-facing scree or snow slopes

Round-trip time: 6–10 hours

Height gain: 1260 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir (unmarked 205351); Gem Trek Canmore–Kananaskis Village, Banff–Assiniboine

In summer, The Tower and its companion valley to the south are one of the more pristine and less visited spots along the Smith-Dorrien/Spray corridor. The ascent route is similar in character to Mount Galatea, although not as steep. With snow on the slope, the glissade descent can be a riot, so take an ice axe. In dry years the peak may be in condition by mid-June, but with a late spring or heavy snowfall, July would be more appropriate.

Drive to the turnoff for Mount Engadine Lodge on Smith-Dorrien Trail–Spray Lakes Road, 7.5 km north of the Burstall Pass parking lot and 38.2 km south of the Bow River bridge in Canmore. There is a very small clearing on the west side of the road; otherwise park on the shoulder. Do not use the lodge’s guest parking lot.

The approach is via Rummel Lake trail, which starts right across from the Mount Shark–Engadine Lodge turnoff and heads south along an old logging road. This logged area has grown in markedly since earlier guidebook editions but the trail is obvious. Before long the path cuts back up to the left, steadily gaining elevation before easing once it reaches the ridge above. You’ll have no problem following it as it continues south, curves left, then drops down to intersect Rummel Creek and cross to the north side of it. Beyond here the trail has been rerouted north from its original location to avoid an avalanche slope, the site of a fatality one winter. The more southerly original trail may also be in use. Idyllic Rummel Lake is a wonderfully scenic spot for a break and is popular with hikers and fly fishers alike, especially on weekends. Note that neither camping nor fires are permitted.

Wander down the left shore to where a trail angles left to meander through subalpine forest and up into beautiful, open, flowery meadows north of the lake. Continue east past the vegetation line and up to the base of the south face of The Tower. Don’t make the mistake of heading for the top too soon. Notches in the ridge will make it difficult to actually get to the summit and may force you to descend a long way in order to do so. The proper starting point is just past a small seasonal pond (206336) which is surrounded by rubble. It typically dries up during July. Head up the rubble slope on the left, noting a third lake in a barren bowl to the northeast visible from higher up. Gradually work your way to the right and toward the ridge. Difficulties vary depending on whether you’re on the face or close beside the ridge, but either way, very little routefinding is needed. While this peak has an excellent access trail and is located in a classic alpine setting, it does not see that many ascents and you may well have it all to yourself while enjoying the spectacular views from the top.

Confusion surrounds the unofficial name. History recalls that Hans Gmoser’s climbing party of 1957 called their first ascent “The Tower,” but their photos clearly show The Fortress, some 3.5 km southeast. It is likely they were actually on Mount Galatea. Apparently, over the years, those strong chinook winds have pushed the name farther north to this mountain. Although the peak doesn’t really resemble a tower, the name does have a better ring to it than “Unnamed 3117.”

Once you’re done pondering this snippet of observational wisdom, return the same way.

South face route on The Tower from Galatea’s ridge.

The foreshortened south face of The Tower as it appears on approach. The route starts just past a small seasonal pond.

Difficulty: A difficult scramble and/or steep snow ascent by the south face and ridge

Round-trip time: 6–10 hours

Height gain: 1280 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Mount Galatea is the finest viewpoint of the Kananaskis Range. Like adjacent summits, the approach is a popular hike visiting larch meadows and lakes. On a clear day you’ll see peaks as distant as Mount Olive on the Wapta Icefields, Howser Towers in the Purcell Range, and at least 10 of the 18 peaks higher than 3353 m scattered around the southern Rockies. The upper section of the route is steep, but lower portions make for a good glissade if you have the right snow conditions and an ice axe. This ascent is more mountaineering than simply scrambling, and you should avoid it if there is much snow left on the upper face. Try from late June on.

Park at Chester Lake parking lot on Smith-Dorrien–Spray Lakes Road, 44 km south of Canmore and 20 km north of the Smith-Dorrien–Kananaskis Lakes Trail junction.

Follow the well-used hiking trail to Chester Lake as for Mount Chester. Once you reach the lake, a good trail diverges left along the north shore, leading past Elephant Rocks and over a gentle rise into a pretty valley immediately north of Chester Lake. Continue upvalley past two small ponds to an obvious large scree pile at the base of Galatea’s south face. Ascend this slope toward a small waterfall. Keep to the right as you ascend, using slabs where possible to reduce some treadmilling. This also avoids the fall-line of stones from eroding cliffs above you.

Continue along the ridge as it curves left near the top, moving onto the face if steps along the ridge present problems. The slope angle steepens noticeably here. When dry this is of small consequence, but if snowy, as is likely in June, it feels dicey to be out on this steep incline once the snow softens up. Even with an ice axe you must use caution along here. After a 2-hour plod up, however, the rapid 10-minute glissade down should be memorable if not exhilarating. Although this peak is easy to approach, it doesn’t see that many visitors.

The summit of Mount Galatea boasts a far-ranging view, and many happy hours could be spent here attempting to identify surrounding and distant mountains. It is common to see parties on Gusty Peak and Mount Chester nearby, as these also draw energetic outdoors folks. If you’re interested in doing The Tower (3117 m), close by to the north, this is an excellent spot from which to survey the line of ascent up its south slopes. Once the wind comes up and the Kananaskis rock has made a suitable impression on you, return the same way.

HMS Galatea was a British cruiser engaged in the historic First World War Battle of Jutland. In mythology, her role as a beautiful sea nymph was a decidedly less militaristic one.

A magnificent panorama taken from the top of Mt. Galatea. Bg: Bogart; K: Kidd; Fi: Fisher; D: Denny; C: Chester; Fr: French; Rb: Robertson; SD: Sir Douglas; Bw: Birdwood; S: Smuts; E: Eon; A: Assiniboine; B: Ball; Rd: Rundle; BS: Big Sister; Sr: Sparrowhawk. PHOTO: BOB SPIRKO

A foreshortened look at Mount Galatea’s steep-looking south face ascent route, which is not quite as steep as it appears. PHOTO: BOB SPIRKO

Difficulty: An easy scramble via southwest ridge

Round-trip time: 5–8 hours

Height gain: 1100 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

The Fortress is the second most popular scramble in the Chester Lake area. For variety, you can combine two approach options to make a loop, visiting entirely different valleys complete with exquisite alpine lakes. From Highway 40, the towering 600 m north face above Fortress ski area does present a fortress-like appearance. Even the turrets are evident. That perspective gives no hint of a gentle shoulder leading easily to the top. Note: Camping is prohibited at Chester Lake. Try this ascent from July on.

Park at Chester Lake parking lot on Smith-Dorrien–Spray Lakes Road, 44 km south of Canmore and 20 km north of the Smith-Dorrien–Kananaskis Trail junction.

Not many parties use this approach to climb The Fortress, despite the lakes being a very pretty setting and scree to the Fortress–Chester col being more solid. The trail uses a series of old logging roads, now also used for biking. Gill Daffern’s Kananaskis Country Trail Guide, 4th ed., vol. 1 contains a detailed description of this approach.

The easiest route to Headwall Lakes is via the colour-coded ski trails. On the south side of the parking lot, find the ski sign and follow the blue loop. After 1 km, turn left onto a road marked blue/yellow; then, in less than 1 km, you reach a junction where a blue loop lies to the left. Keep right, angling up a long hill flagged with yellow markers. Upon reaching a logged area on a ridge, continue on the yellow road until it fords Headwall Creek. Many people follow the stream to the upper valley from this point. If you continue uphill and look along the edge of the cutblock, a better trail can be found that leads through forest to the first meadow.

From Headwall Lakes, continue into the stony upper reaches of the valley and climb to the Chester–Fortress col. Although the summit appears close from this point, allow a full hour, as there are still some 325 vertical metres to gain.

Surmount the summit block easily on the left (northwest) side. Far below the sheer north face lies Fortress Lake, with an awe-inspiring amount of atmosphere between the two. This vertical face was first climbed by Glenn Reisenhofer and Jeff Marshall way back in 1988 when both they and the peak were much younger.

Mount Galatea, the dominant peak to the northwest, is another pleasant scramble, as are adjacent Mount Chester and Gusty Peak to the east and north respectively.

Hike the well-used trail to Chester Lake as for Mount Chester. Once you reach the lake, follow the left shoreline and trails around to the waterfall and into the upper valley. At first there are meadows, mosses and a bubbling stream, but farther back this jumbled landscape of boulders becomes increasingly barren. Shortly before a tiny pond, angle up talus on your right to gain the Chester–Fortress col. Snow often lingers on this shadowy slope and may allow a fast and exciting descent if you’ve brought along an ice axe. From the col, the route coincides with the Headwall Lakes option.

The Fortress from Chester Lake approach. C: Fortress–Chester col.

L–R: Summit view of Mount Assiniboine, Gusty Peak, Mount Galatea and The Tower, showing ascent routes for the foreground three. PHOTO: GILLEAN DAFFERN

Difficulty: A moderate scramble via scree and slabs on southwest side

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 1150 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Mount Chester offers fine scrambling, beginning in alpine meadows near a popular lake. The ascent is a personal favourite of mine and gives an excellent return for the effort. If you go, please treat this fragile area with care. Scars from big boots do not heal quickly in the harsh climate found at this elevation, and this ascent is now one of the most popular in Kananaskis. Heavy visitor use has damaged the lakeshore meadows, and as a result, camping is no longer permitted. Regardless, the outing is a fine day trip and is possible from about July on. Chester Lake trail is closed to hiking through June.

Park at Chester Lake parking lot on Smith-Dorrien Trail–Spray Lakes Road, 44 km south of Canmore and 20 km north of the Smith-Dorrien–Kananaskis Trail junction.

Follow the popular hiking trail to Chester Lake. The path begins as an old logging road and later dwindles to a footpath as it enters forest. Within an hour you emerge into open alpine terrain and larch meadows alongside the stream that drains Chester Lake.

Cross the stream and follow the lakeshore trail, which leads past meadows to the big gully and the col west of Mount Chester. Hike up the broad gully to this saddle. It is also possible, if less direct, to gain this col from Headwall Lakes to the south or to use that valley as an optional exit. During prime season, late July to mid-August, you may discover a profusion of wildflowers eking out a fleeting existence on these harsh slopes. After basking in a view of the western skyline, turn your gaze eastward. Firm, knobbly slabs give an enjoyable scramble to the summit 300 m above. If you prefer scree instead, more is found farther right.

Although this point is a little lower, the summit panorama is as good as that seen from nearby Mount Galatea. On a sunny summer day, it is most likely that others will be enjoying the spectacle as well. Fifteen people sharing the summit on a sunny Sunday is not unheard of on Mount Chester. Peaks such as Farnham Tower, shaped a bit like a smokestack, are visible 90 km west in the Purcell Range. Loftier, closer peaks include Mount Assiniboine (the “Matterhorn of the Rockies”), Mount Sir Douglas and Mount Joffre, all of which soar to more than 3353 m (11,000 ft.). This vantage point also affords the opportunity to study the equally easy ascent routes for The Fortress and Gusty Peak northeast and north of you, respectively.

Chester, Galatea, Engadine, Indefatigable, Shark and several other peaks in this area borrow their names from cruisers and destroyers involved in the Battle of Jutland. This was a notable conflict fought during the First World War, and its significance is twofold: it was the only time when the entire fleets of both Britain and Germany were engaged; and it ended in a stalemate.

Evening alpenglow on Mount Chester ascent route seen from Smith-Dorrien Trail. G: gully; S: saddle.

The summit of Mount Chester gives a fine view of several more scramble peaks. T: The Tower; Ga: Mt. Galatea; Sp: Mt. Sparrowhawk; B: Mt. Bogart; Gu: Gusty Peak. PHOTO: SONNY BOU

Difficulty: Easy ascent via south scree slopes

Round-trip time: 5–8 hours

Height gain: 1100 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir (unmarked at 227322); Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Gusty Peak is another easily ascended summit near scenic Chester Lake and it sits close to mounts Chester and Galatea and The Fortress. Many more parties ascend it these days, but it is still noticeably less crowded than Mount Chester. The view is fine and problems are few. Try from July on.

Park in the Chester Lake lot on Smith-Dorrien Trail–Spray Lakes Road, 44 km south of Canmore and 20 km north of the Smith-Dorrien Trail–Kananaskis Lakes Trail junction.

Hike to Chester Lake. Once there, follow the left shoreline and trails around to the waterfall and into the upper valley to the northeast, as described for The Fortress. Go almost to the Chester–Fortress col and along the west shore of a tiny pond. Gusty Peak is on your left. Facing it (north), angle up diagonally to the right on scree slopes, following the tilt of the strata, which should lead right toward the main summit at the easternmost end. The foreshortened view fools folks into believing the high point sits directly above, but this line instead leads to steep terrain and the lower west peak. Traversing between the two is unpleasant and unnecessary.

If free of snow, this ascent is little more than a steep trudge up (and back down!) a rubble slope, and the only stumbling block is the abundant loose limestone variety underfoot. This rock, from the Banff Formation of 360 million years ago, is prevalent throughout the Front Ranges and sharp eyes might find horn coral fossils here and in similar places.

Gusty Peak is an unofficial name given by the first-ascent party of Alpine Club members from Calgary in June 1972. High winds accompanied their ascent and snow persisted underfoot. Spring was late that year and by mid-month, runoff records were set on many major rivers both in British Columbia and Alberta.

Viewed from Mount Chester in prime larch season, ascent routes for T: The Tower; Ga: Mount Galatea; and Gu: Gusty Peak. PHOTO: MATTHEW HOBBS

Difficulty: Moderate scramble via the north ridge; brief exposure

Round-trip time: 6–9 hours

Height gain: 1000 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

In spite of its lower elevation, Mount Shark is an excellent vantage point and a pretty decent scramble. Technical difficulties are few, but lack of a recognizable path beyond Karst Spring probably dissuades the curious wanderers from exploring much farther. Try from July on.

Drive to Mount Shark–Engadine Lodge access road on Smith-Dorrien Trail–Spray Lakes Road, 6.4 km north of the Burstall Pass parking lot and 38.2 km south of the Bow River bridge in Canmore. Follow this road to its end, where there is a parking area and trailhead.

From the parking area, hike or bike the wide trail 4 km to Watridge Lake. Continue on foot around the lake and up to Karst Spring below the north ridge, the normal access route. Head straight up the hillside and work your way left. With a little persistence and the odd hint of an animal trail, you steadily leave the din and crowds below. This short stretch of bush up to the ridge is unpleasant but necessary. This ridge can also be gained by ascending an open avalanche slope on the east side.

As you gain treeline, feathery-needled Lyall’s larch replace scattered patches of spruce. Head left to gain the ridge. Soon you’re enjoying pleasant scrambling up angular, slabby limestone typical of the Front Ranges. On a calm day, Spray Lake mirrors Mount Lougheed in deep shades of aquamarine. Just when you’re having a good time, the ridge narrows. Ah, this mountain will not be won so easily! Depending on your route, challenges will vary, but this section should never actually be difficult. Brief exposed sections of the crest can often be bypassed on the right. After a couple of false summits and rotten rock, you finally reach the crumbling summit. “Superb” only begins to describe the view. Lush, green valleys, sparkling lakes and icy, precipitous faces meld into a magnificent landscape.

Return the same way. Once you reach treeline, you can simply head down through bush toward noisy Karst Spring. You’ll find bushwhacking downhill to be much easier.

Mount Shark from the east. The route ascends the right-hand skyline ridge.

Difficulty: Difficult scramble with loose rock and brief exposure

Round-trip time: 5–7 hours

Height gain: 770 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir (unmarked 149301); Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Shaped like a clenched fist thrusting skyward, this craggy, unofficially named little peak boasts an exciting finish. The imposing vertical rock walls on the east side impart an air of futility, despite its comparatively low elevation. The secret lies in hiking around to the south flanks – hidden from the road – to an easier, more reasonable line of ascent. Since the first edition of this book, the summit now sees much more traffic and has somewhat less loose rock as a result. A helmet is advisable in case of rockfall from other parties. Try from late June on.

Drive to the Mount Shark–Engadine Lodge access road on Smith-Dorrien–Spray Lakes Road, 6.4 km north of the Burstall Pass parking lot and 38.2 km south of the Bow River bridge in Canmore. Follow this road west for 900 m, crossing Smuts Creek en route, and take the first left turn onto an old logging road. Park here.

From the parking area a few metres off the Mount Shark access road, walk south along an old logging road. Within some 30–35 minutes, just before the road drops to Commonwealth Creek, bear right on another logging road, well trodden and usually flagged, which leads toward the noisy stream. A rough path on the north (right) side of the creek continues into Commonwealth Valley.

Hike along the trail for about an hour to open, marshy meadows and wide avalanche slopes below the peak on your right. These open slopes give access to the connecting ridge between The Fist and its westerly neighbour, Mount Smuts. The most direct (and least bushy!) route is to follow the small drainage up the avalanche slope. There should be smatterings of a trail here. You will have gained most of the required elevation for the ascent upon reaching the Smuts–Fist ridge, and this is a good spot for a break before proceeding.

From the ridge, a trail continues up scree toward the peak, heading for the gully to the left of the big, free-standing rock fin. While you can go up either side of this fin, the left side is the logical choice. If you choose the right side, you’ll have to scramble over a dividing wall higher up anyway.

There are two ways to reach the summit from within this gully. Option one is to continue all the way up the gully to a skyline notch at the end. Here, above a steep drop down the east side, make a sharp left turn and scramble up onto airy ledges and rubble for the last few metres. This bit has less loose debris than in years past but is still exposed. A slip would likely be fatal. Alternatively, a short distance before the skyline notch, you can climb a steep (2 m) wall on small holds to gain a gully on the north side. This rubbly gully quickly widens and leads easily to the top. Fortunately, these two options are only minutes apart if you want to compare or try each.

When I first ascended this peak, an inquisitive old mountain goat peered down at me from above, watching with smug amusement. My slow, cautious movements no doubt allayed any apprehensions, and, oblivious to the terrific drop below, he scampered away, completely unfazed by the exposure.

The Fist from Commonwealth Creek, showing ascent route from Smuts–Fist ridge to gully.

The Fist as seen from Mount Smuts. The route normally goes left of fin, then to the notch, or turns left just before the notch.

Difficulty: Difficult climber’s scramble via the slabby south ridge; one of the most difficult ascents in this guide

Round-trip time: 6–9 hours

Height gain: 1075 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Mount Smuts presents demanding scrambling on steep, slabby limestone ribs. Sections of the route are also exposed – “exhilarating” comes to mind. Some parties don a climbing rope; many others probably wish they had one for at least one section. Capable climbers and scramblers will find it unnecessary IF the rock is dry, but only a few parties make the summit each year. Many back off and some have required rescuing. Several pitons are evident on the route now. Try from July on or whenever all snow is gone.

Drive to Mount Shark/Engadine Lodge access road on Smith-Dorrien Trail–Spray Lakes Road, 6.4 km north of Burstall Pass parking lot and 38.2 km south of the Bow River bridge in Canmore. Follow the access road west across Smuts Creek for 900 m and make the first left-hand turn onto an old logging road and into a parking area.

From the parking area, walk south along the old logging road. After some 30–35 minutes, just before the road drops down to Commonwealth Creek, bear right and follow the well-trodden trail that leads back into the valley. A rough path on the north side continues upstream.

Hike through forest to meadows and a meandering stream, passing The Fist and continuing toward Smuts Pass. This is the high saddle at the west end of the valley between mounts Birdwood and Smuts. Just a wee bit before the pass, on the north side of the valley, head up a large scree cone toward a scree gully above. Although you can’t tell by the foreshortened view up this gully, the summit of Mount Smuts lies to the right. Trudge up this gully; it narrows higher up before the left wall peters out completely. Now you must ascend the slabby right-hand wall – look for a cairn. From here, nearly vertically tilted ribs of firm Palliser limestone rise directly to the summit, alternating steep rises with stretches of plodding.

Once you begin the real scrambling there isn’t too much variation possible. If you ascend the exposed rib to the left it is more demanding than staying in the gully to the right. The exposed rib is rated 5.4–5.5 climbing, whereas the gully is more like 5.2–5.3, which is at the upper end of scrambling. Upon gaining the right-hand wall above the gully, you’ll quickly find out if it’s to your liking. Remember, unless you summit, you will be descending this same way, and that will be even harder – as in scarier! The crux is a short, smooth slab with a giddy drop on the east side.

If the north ridge is free of snow, it offers an easier route down. Descend to the first big promising-looking gully on your left. Scramble (grovel) down it until it steepens. Here it becomes obvious that it would be easier to simply traverse out of the gully on ledges to your left (south) and reach easier terrain. Angle down rubble and scree slopes below, then turn left and hike south down the drainage toward Birdwood Lakes, small ponds immediately west of Mount Smuts and Smuts Pass. From the lakes, go left (east) up over Smuts Pass to the foot of your ascent ridge again.

Jan Christiaan Smuts was a Commonwealth statesman and general of the Union of South Africa.

The exciting south ridge of Mount Smuts – no place for novices. PHOTO: LEON KUBBERNUS

Difficulty: Moderate scramble via southwest face

Round-trip time: 5–10 hours depending on return route

Height gain: 875 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

Commonwealth Peak, shown only on newer maps, will never be an all-time classic scramble, but as a getaway from the crowds, it is worth ascending. The view of the Kananaskis Range is excellent, and an alternative exit exists to extend your day if desired. Take runners for the boggy approach, and a bike saves about an hour if returning the same way. Carry an ice axe for early summer visits. Try from about July on.

Park at the Burstall Pass parking lot on Smith-Dorrien Trail–Spray Lakes Road, 44 km south of Canmore and 20 km north of the Smith-Dorrien Trail–Kananaskis Lakes Trail junction.

Hike (or bike) 3.5 km along Burstall Pass trail to where it becomes a single track (leave bikes here), then descend to the gravel outwash flats. The hulking peak on the skyline to the northwest is Mount Birdwood, and the pointy summit immediately east is Pig’s Tail. Unimposing Commonwealth Peak (165275), your objective, is to the right (east) of Pig’s Tail. The ascent route goes up the broad avalanche gully to the col between these latter two peaks.

The drier crossing is upstream closer to Burstall Pass trail; otherwise, slosh directly across calf-deep bog and braided streams to the ascent gully. In 2013 one innocuous, narrow channel of dirty water here was crotch-deep – good thing I probed first. A decent animal trail exists in mature forest to the left of a gravel outwash that has flowed down almost to streamside. Flagged in 2013, this path is worth finding. From the col, a perfect view of The Fist and Mount Smuts is revealed, and you’ll probably decide to have a bite while eyeballing just where to go next. If you wander out onto the cornice, the decision will be made for you: you’ll plummet straight down.

The ascent route follows a big scree ramp above the col that angles up and to the right of steeper rock, aiming for the right-hand skyline. Treadmill up this rubble, whereupon a trail leads around into a wide gully cunningly tucked behind. Thrash up this loose gully as it rises to the left, staying to the left as you go. After narrowing, this gully spits you out on open slopes of blocky, broken rock almost directly above the col. Turn right and carefully scramble up some 20 m of steepish, crumbly rock to the summit ridge, which is fairly narrow. It is in stark contrast to the rest of the route, and evidently not everyone continues up this last bit.

Although you are a little lower than most nearby peaks, the view is nonetheless remarkable, especially the panorama from mounts Nestor to Chester. Notice Commonwealth Lake far below, deep in the forest immediately north. Previous editions described alternative but longer exit routes north from the col past the lake but few parties bothered. On your return, you’ll find all that loose rubble actually proves useful. Be cautious, though, where it lies on steep slabs in the middle of the gully, just before the route traverses over to the right (west). Keep well to one side or the other here.

Commonwealth Peak ascent route from the col as seen from Pig’s Tail. G: gully.

Difficulty: A moderate scramble via north ridge to southwest side

Round-trip time: 7–10 hours, including ascent of unnamed (Cegnfs)

Height gain: 1100 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; 82 J/11 Kananaskis Lakes (unmarked 205230); Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region, Banff–Assiniboine

Mount Murray in the French Creek area involves a bit of bushwhacking, a lot of scree bashing and a short scramble up a chimney to the summit. You ascend a lower peak en route. Mount Murray is at 205230 (bottom of map 82 J/14) and not shown on all maps. Very few who ascend it would revisit the relentless rubble, so plan your trip accordingly. Try from July on.

Park at Burstall Pass parking lot on Smith-Dorrien Trail–Spray Lakes Road, 44 km south of Canmore and 20 km north of the Smith-Dorrien–Kananaskis Trail junction.

The original start to French Creek from Burstall parking lot is via the old dirt logging road over culverts and past silty Mud Lake. Where the better-used Burstall Pass trail curves rightward at the top of the hill, continue straight ahead instead. Now you are on an old logging road reverting to an unmaintained trail. It goes up a hill, then gradually descends, whereupon you wade French Creek (knee-deep). The first waterfall is just upstream from this crossing but you don’t see it.

An alternative start mentioned by Gill Daffern in her Kananaskis Country Trail Guide (4th ed., vol. 1 at 275) avoids wading French Creek. The first kilometre is bike-able. From the parking lot, follow the good gravel access road that curves left before you even cross the culverts. This road ends at a diversion spillway for French Creek, where you cross a wooden bridge. French Creek is to the right. The continuation is an old logging road which as of 2013 had flagging. It reverts to a narrow, bushy trail, heads left up a hill and then turns sharp right. Flagging should lead you back down to meet the original approach road just past the wadeable crossing point. It isn’t hard to follow, but for more detail consult Gillean’s book. If French Creek had more visits this route would improve markedly, but it is already much better than what lies ahead.

About 30 minutes from the parking lot (via the original trail), the old road crosses to the right-hand (west) side of French Creek. Right here the valley opens, showing green lower slopes of Mount Burstall above on the right. You do not cross the creek here; stay to the left. Keep on a trail which dodges left into forest, then perhaps back to the creek. The high-water trail branches left into forest just one slight bend before the 15-m-high second waterfall. Follow this route as it continues through forest; it may be flagged. If you miss this first high-water trail, trudge up the vast outwash of rock debris just before the waterfall, watching for flagging to show where to rejoin the trail through the forest. This debris pile has washed down from the east ridge of Cegnfs, the point above at 205242. You’ll encounter avalanche debris (downed trees) shortly beyond, and mere minutes past this when the trail drops and levels, a more important drainage angles slightly south by southeast towards Mount Murray. Right about here the French Creek trail goes to the right and rises up a small hill into woods. The drainage for Mount Murray heads off to the left, so stay left and follow it, as it is quite open. You soon encounter huge amounts of debris also washed down from near Cegnfs summit in June 2013. Near treeline this drainage is 2 m deep and leads to a notch in the hillside fittingly called a “rock gate” by Bob Spirko. A huge boulder perches just inside this gate. Once inside the gate, exit the gully on the right side where convenient and continue easily to the top of Cegnfs on open rubble slopes.

From Cegnfs, descend to the col and trudge up massive amounts of rubble. The path circles around the summit block to the southwest side and finishes with a scramble up a chimney through a rock band, the only interesting diversion of the ascent. On your return, do not descend directly from the col to the valley, as a band of cliffs lies below. You need not reascend Cegnfs; instead contour around east far enough to outflank the rock bands.

General Sir A.J. Murray was chief of the Imperial general staff in 1915 and general officer commanding in Egypt in 1916–17. Cegnfs is an unlikely and unofficial initialism derived from the names of the first-ascent party. SEGniffs is the most likely pronunciation.

Cegnfs and Mount Murray from East Ridge of Mount Burstall. A: Avalanche debris; R: Rock gate; C: Cegnfs; M: Mount Murray.

Difficulty: Difficult, exposed scrambling for final 100 m of east ridge

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 870 m

Maps: 82 J/14 Spray Lakes Reservoir; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes & Region

A short, simple approach makes this minor summit a logical choice when ambition, good weather or time are lacking. The view is rewarding and includes big peaks around French and Robertson glaciers. The route is largely straightforward but the exposed and loose summit ridge keeps the crowds at bay. Try from about mid-July on.

Park as for Mount Murray.

Follow the Burstall Pass trail for about 40 minutes. Ten minutes past a 3-m-high boulder lying on the trail, turn left at a cairn and follow the beaten path through forest to an avalanche gully where a steep slope of fine black shale leads to the east ridge. The summit is 300 vertical metres above this ridge. After admiring mounts Murray and Cegnfs to the southeast, turn right to follow sheep and human trails up the grassy hillside. Tedious rubble leads to the final ridge, from where the large summit cairn is visible. This last section is shattered and may look scary, but fortunately much of the route stays below the ridge traversing ledges to the right. Care is required because of the loose rock and exposure.

Ledges below the crest lead toward a broad slab in a corner capped by a large overhanging block. The obvious route is a well-trodden but narrow gully/crack line angling up right to regain the ridge. The summit is just beyond. If desired, you can continue to the lower west end of the mountain, but expect one tricky exposed bit at a notch. Most folks don’t bother. Once your senses have been suitably sated, return the same way.

Just so you’re not left hanging, H.E. Burstall was a Canadian lieutenant-general in the First World War.

Mount Burstall seen from the lower slopes of Commonwealth Peak. C: crux.

Near the crux on Mount Burstall, showing the route to the summit.

Difficulty: Difficult scrambling

Round-trip time: A very long day

Height gain: 1280 m

Maps: 82 J/11 Kananaskis Lakes; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes

Prairie Lookout is a dominant peak west of Smith-Dorrien Highway which when viewed from near Mud Lake displays deep, V-shaped folds near the top. It rises directly above French Glacier at 197221, just beyond Mount Murray. The ascent route via the slabby west face is reached by an unmaintained trail up French Creek. Not many parties venture this far up French Creek in summer. In winter, backcountry skiers have a ski traverse as their goal and as a result the peak sees few ascents. The slabby parts are better when dry, and since this is a heavy snowfall area, try from about July to September. There are beautiful, meadowy camping spots in the upper valley. Unless you are familiar with the approach, deadfall and routefinding make this ascent a bit involved as a day trip. Helmet and ice axe advisable.

Park in the Burstall Pass lot on Smith-Dorrien–Spray Lakes Road in Kananaskis Country, 44 km south of Canmore and 20 km north of the Smith-Dorrien–Kananaskis Trail junction.

The original start from the Burstall Pass parking lot is via an old logging road over culverts and past silty Mud Lake. Where the better-used Burstall Pass trail curves rightward at the top of the hill, continue straight ahead. Now you are on a much less used old logging road, reverting to an unmaintained trail. It goes up a hill, then gradually descends, and you wade French Creek (knee-deep). The first waterfall is just upstream from here but you don’t see it.

An alternative start mentioned by Gill Daffern in her Kananaskis Country Trail Guide (4th ed., vol. 1 at 275) avoids wading French Creek. The first kilometre is bikeable. From the parking lot, follow the good gravel road that curves left before you even cross the culverts. This road ends at an overflow spillway crossed by a wooden bridge. French Creek is to the right. The continuation is an old logging road which as of 2013 had flagging. This track reverts to a narrow, bushy trail, then turns left up a hill, then sharp right. Flagging should lead you back down to meet the original approach road just past the aforementioned wading spot. It isn’t at all hard to follow, but for more detail consult Gillean’s book.

About 30 minutes from the parking lot (via the original trail), the old overgrown road crosses to the right-hand (west) side of French Creek. Do not cross the creek here, however. Continue on a trail which dodges left into forest, then perhaps back to the creek. The high-water trail branches left into forest just one slight bend before the 15-m-high second waterfall. The winter ski route sometimes goes up directly left of this waterfall but the 2013 rains obliterated the summer trail to it, so back up a bit and take the high-water route. This continues through forest and may be flagged. If you miss the first high-water trail cut-off, trudge up the vast 5-m-high outwash of rock debris just before the waterfall, watching for flagging to rejoin the high-water trail. Add more flagging if you have some. Cross a gravelly drainage (193240) and about 5–10 minutes beyond, when the trail drops and levels, you encounter another drainage angling slightly south-southeast which goes to Mount Murray. Right about here the French Creek trail goes to the right and rises up a small hill into forest. Follow it.

For most of the way up the valley, the route alternates between bushwhacking through forest, (hopefully) following flagging, or tramping creekside through willows. Watch carefully for flagging and a semblance of trail here and there as you continue up the main valley. In fact, you could carry flagging to reflag faded bits. Debris and deadfall are unavoidable but thankfully they lessen as you go. As of 2013 I found the best rule of thumb was, when in doubt, take the trail back up into forest rather than stay alongside the creek.

Allow some 2.5–3 hours to reach the upper valley at 2190 m, where open larch forest and views of Mount Robertson await. Prairie Lookout is beside you on the left but the ascent route is around the corner, not yet visible. Mount French is the next peak, displaying vertical slabs and gullies from this aspect. It is much more challenging and described separately.

From open meadows at treeline, hike up the wide draw between Prairie Lookout and the huge moraine sitting straight ahead. You lose a small amount of elevation as you round a slight corner to arrive below the slabby west face of the objective. Study the lower face as you approach. Above it lies a more broken-up, less steep section of rock which is your starting point for the face above. There are numerous possibilities here. We went directly up from the highest scree point, then traversed to the right to a small gully and straight up slabs to easier ground above. Although there are many possible lines, getting up this lower part is more challenging than the rest of the scramble. Allow 2 hours to the ridge. Then turn left, and in about 30 minutes you reach the top with very minimal scrambling involved.

Prairie Lookout’s summit provides a fabulous viewpoint, but when we were there I was not on the lookout for prairies but for thunderstorms building nearby and spent minimal time enjoying scenery. As you probably surmised, there is no simpler way down; you must descend the same way.

Prairie Lookout is an unofficial name that has been around for many years.

This foreshortened view from French Glacier suggests many route possibilities exist up Prairie Lookout’s west face.

Difficulty: Difficult, exposed; glacier travel; a climbing/mountaineering scramble

Round-trip time: 4–6 hours from upper French Creek; 9–13 hrs from parking lot

Height gain: 1330 m

Maps: 82 J/11 Kananaskis Lakes; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes

Mount French, third-highest in Kananaskis, is another of the more challenging peaks bordering French and Haig glaciers. Like nearby Mount Jellicoe and Prairie Lookout, this summit is readily done from a camp in Upper French Creek or as a long day trip. A small amount of glacier travel is required, whereupon tedious rubble leads to a breathtakingly narrow summit ridge. Difficulties are comparable to Mount Smuts. Try from mid-July on. Ice axe suggested.

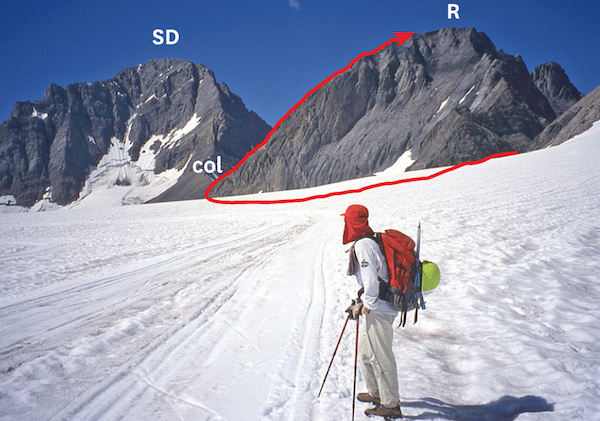

The approach up French Creek is the same as for Prairie Lookout. From upper French Creek near the last larches and meadows, at 2190 m, Prairie Lookout is on your left and Mount French is the next peak, showing vertical slabs and gullies. Step one is to reach Haig Glacier by first ascending French Glacier. French Glacier can be mostly avoided by staying up to the left of the big moraine well above the glacier, passing Prairie Lookout, then eventually meeting the glacier much farther up.

Continue through the portal between mounts French and Robertson out onto the white expanse of Haig Glacier. Although parties do travel this part of the two glaciers unroped and I have not seen any evidence of crevasses here, the safest way is roped up. The choice is yours; don’t blame me if you fall in a deep hole and die.

Turn left at Haig Glacier, wander some 100–200 m along the base of Mount French and head up the slope toward the ridge wherever you see fit. These southwest slopes are mercilessly loose scree, so any bit of slab or rib is a welcome respite. Ski poles are a must to make any headway. On my late-July ascent, snow alleviated some of the tedium. Farther out on the glacier, notice the summer training circuit of Canada’s national cross-country ski team.

Once on the ridge, the route ahead looks serious, but you may find it is not quite as bad as it looks. Bad enough, though! Because you’re on a ridge, little routefinding is required, but watch for loose rock. The rock is usually solid where needed most, although the sheer 500 m drop to French Glacier is still gut-wrenching. Difficulties start almost immediately, and while some parts of the ridge can be avoided on the south (right) side at the narrow, exposed crux near the summit, I crossed à cheval (straddling) twice. There is simply no room for a wobble or slip here. Once beyond this, a short, steep gully leads to the summit, snow-filled in July, perhaps icy later on, and somewhat exposed.

From magnificent Mount Sir Douglas to more distant Mount King George, from meadows to lakes, views of the environs are definitely worth all that effort, ranking near the best of any K-Country ascent. You can readily eyeball the route on adjacent Prairie Lookout, too. When you’ve re-established equilibrium, return the same way. You’ll discover that the ridge is fairly challenging in reverse as well, but at least the rubble helps rather than hinders your descent.

Sir John Denton Pinkstone French was field marshal and commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force in France during the first year of the First World War. His successor, Sir Douglas Haig (as in the glacier) was desperate for a symbolic victory at Passchendaele Ridge, which was held by the Germans. Because of this, in 1917 nearly 16,000 Canadians lost their lives and yet Haig is honoured with a glacier bearing his name.

Mount Jellicoe is the next peak south of Mount French but is a cruise by comparison. If you are already in the area you might consider trudging up the loose, rubbly southeast side of this mountain. From a camp in French Creek, and with some determination, both peaks could be done in a day. Although the Haig is a “tame” glacier and cross-country skiers train on it, you should probably still rope up when travelling across it. There might be a cold, dark crevasse just waiting for you.

If starting from upper French Creek, allow some 3–4 hours to the summit. It would be a very long day from the parking lot. Confusion exists regarding the height of this peak. The last edition (1979) of the guidebook Rocky Mountains of Canada South lists it as 3246 m but it is noticeably lower than 3234 m Mount French. Topo maps show it touching the 10,000-foot contour. Older guidebooks list it as 10,165 ft. (3100 m).

The route ascends southeast rubble slopes, which can be gained from two directions: French Creek or Turbine Canyon. From French Creek–Haig Glacier you trek past Mount French and pass below Jellicoe’s impressively steep west-facing walls. On this approach you have to lose elevation before you can get onto rocky slopes of Mount Jellicoe and you must also cross 1.7 km of glacier. By comparison, no glacier travel is required if approaching from Turbine Canyon, and that’s the route we’ll describe here. Tramp up a cairned and beaten path to, and then onto, moraines. This is the trail used by ski racers going to the Beckie Scott High Performance Training Centre. The centre’s buildings sit just below the glacier; stay to the right of it to gain the ascent slopes. Once you’re on the mountain, the way up is evident. Nothing much except masses of loose rubble separates you from the summit ridge – choose a line and head for anything that looks solid. From the false summit a stretch of easy scrambling leads to the true summit, this being the only interesting part of the whole ascent. Return the same way.

Sir John R. Jellicoe led the Royal Navy at the Battle of Jutland in the First World War, according to Peakfinder.com. Albertan Beckie Scott, for whom the aforementioned training centre is named, is the first North American woman to win an Olympic gold medal in cross-country skiing.

Mount French route as seen from Mount Jellicoe.

Telephoto shot of mounts F: French and J: Jellicoe routes. H: Haig Glacier; T: Turbine Canyon approach.

Difficulty: Difficult, exposed scrambling; glacier travel; a mountaineering/climbing scramble

Round-trip time: 9 hours from camp in upper French Creek; 14+ hours as day trip

Height gain: 1280 m

Maps: 82 J/11 Kananaskis Lakes; Gem Trek Kananaskis Lakes

Straddling the Continental Divide, Mount Robertson towers above French Glacier and can be seen from 500 m south of Mud Lake on the Smith-Dorrien trail. The approach involves 3 km of glacier travel en route to the southwest ridge, which elevates this ascent to a mountaineering scramble. While winter ski parties regularly cross this same area unroped, you should probably rope up in summer, as there may be crevasses. The lower part of the ridge is easy but becomes narrow and exposed higher up, somewhat similar to Mount Smuts. This is not a good choice for your first difficult scramble. A camp in larch meadows of upper French Creek works well as a base and allows ascents of adjacent Prairie Lookout and mounts French and Jellicoe. For properly equipped parties familiar with glacier travel, try from about July on. Note: This ascent ridge can also be reached from the Burstall Pass trail by ascending much more crevassed and steeper Robertson Glacier, which is a shorter but more technical and dangerous undertaking.

The approach up French Creek is the same as for Prairie Lookout. When you emerge from forest in upper French Creek you have a good view of the steep walls of Mount Robertson rising high above the right-hand side of French Glacier. Most of the ascent route is on the west side, unseen from here.

Step one is to reach Haig Glacier by first ascending French Glacier. Much of this can be avoided by staying up to the left alongside the big moraine, past Prairie Lookout, then eventually sidehilling along to meet the glacier farther up, losing as little elevation as possible. Continue through the portal between mounts French and Robertson out onto much larger Haig Glacier, noting the wind-scoured moat around the southeast corner of Mount Robertson. You’ll be surprised how much farther away this portal is than it appears.

Turn right and head west across Haig Glacier toward the Robertson–Sir Douglas col (182201). The route ascends the skyline (southwest) ridge from the right-hand (east) side of this col. In winter the usual line is more or less straight up from the low point of the glacier, right below the col, but in summer you can grovel up sooner. Allow some 3 hours from a camp in upper French Creek to the Robertson–Sir Douglas col.

From the col, trudge up broken rubble with a fine view of Mount Sir Douglas (3411 m) behind you. Although this part is a mere plod, the drop alongside increases dramatically as you ascend. Higher up, the route becomes interesting and exposed as you detour around pinnacles. This ridge gets so narrow near the top that we shed our packs before attempting the finale. Here you must drop down on the right-hand side of the ridge to a ledge some 10 m lower and traverse this until able to regain the ridge and the first summit. If you are still game, it is possible to descend steep, slabby rock to a gully on the right in order to reach an exposed, slightly higher point. It is an exciting ascent, with more than enough exposure to kill if you slip.

Once you’ve been sufficiently awed by the panorama, or realize that your lunch is back there in your pack, descend the same way. We discovered that during our absence, a mischievous raven had somehow unzipped the top pocket of each pack and scattered gloves and toilet paper all over the slope. Those birds have a great sense of humour. Not needing wheels, though, the bird thoughtfully left the car keys.

Mount Robertson is named for Field Marshal Sir William Robert Robertson, Britain’s Chief of Imperial General Staff in the First World War.

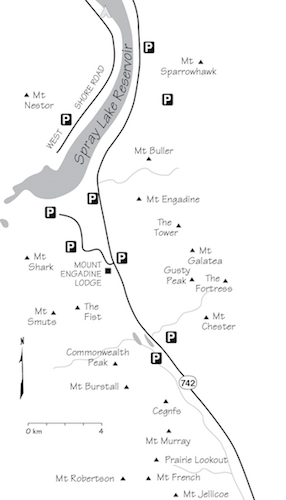

Mount Robertson’s challenging ascent route crosses Haig Glacier to the col and follows the exposed southwest ridge. Notice XC ski tracks on glacier. SD: Mount Sir Douglas.