Mount Galwey 2348 m difficult

Mount Crandell 2378 m moderate

Bertha Peak 2440 m easy

Mount Carthew 2630 m easy

Buchanan Peak 2409 m difficult

Mount Alderson 2692 m easy

Mount Blakiston 2910 m moderate

Hawkins Horseshoe 2683 m moderate

Mount Lineham 2730 m easy

Akamina Ridge 2600 m moderate

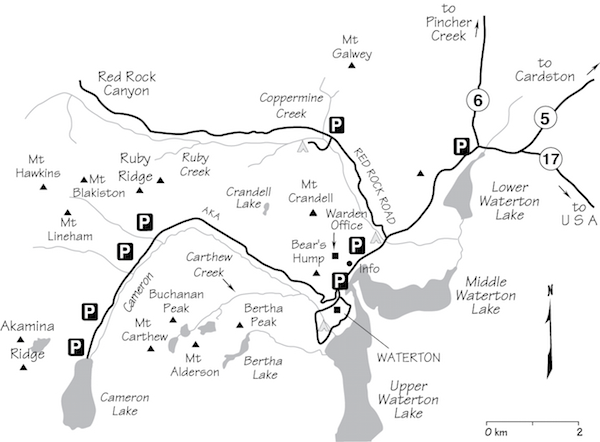

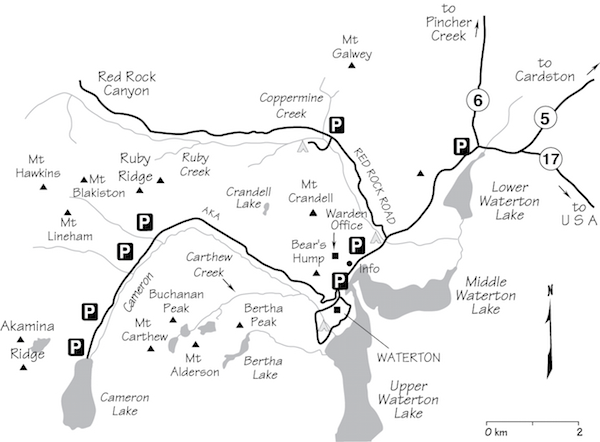

Waterton Lakes National Park, the southernmost area covered in this book, is the Canadian section of International Peace Park, which also includes Glacier Park on the US side of the border. Though small, this 518-square-km preserve in the southwest corner of Alberta is a popular getaway for southern Albertans, boasting a fine network of hiking and backpacking trails. So far, Waterton has avoided the crass commercialism and overdevelopment that bedevils Banff and Jasper. Visitors familiar with those towns will welcome the quieter pace found here.

Serious mountaineering or climbing opportunities are scarce in Waterton owing to the poor quality of rock and absence of glaciation. Some of the oldest sedimentary rock in the Rockies is found here but it has not improved with age. The enthusiast will still find a few good scrambles, but many ascents, though scenic, are simple scree walk-ups. Compared to Lake Louise, Waterton offers a kinder, gentler landscape. Mountain peaks are smaller and ascents typically demand correspondingly less effort.

Waterton Park is notorious for wind. Gales seem to blow regularly here, to the joy of board-sailors but to the chagrin of campers in the town campground. For many, setting up camp here is a defining moment that reveals that not all tents are created equal. In both winter and spring, Waterton is real chinook country. Chinooks are warm, westerly or southwesterly winds that arrive sporadically during the coldest months and promote rapid snow melting. This helps guarantee a little longer scrambling season than what can be expected farther north. If snow persists in Kananaskis and Bow Valley, try heading to Waterton for a spring weekend.

Although Waterton lies next to the prairie, its craggy landscape has been altered by past glaciation. Mountain walls have been sculpted into rugged sentinels. Many peaks display high, castellated towers of horizontally bedded layers. One might expect such striking attractions to guarantee sound rock, but unfortunately it is generally poor and untrustworthy. Colourful red and green outcrops of argillites are also prevalent in the mountains. These are a type of mudstone, but not surprisingly this too is generally flaky and unsound. The exception to this is a locally widespread 4–8 m thick layer of black igneous sill that is 780 million years old. I must thank Keith Dewing of the National Research Council office in Calgary for identifying it – with my limited geological knowledge, I only knew that it was black. This band is readily visible near the top of peaks like mounts Galwey and Blakiston and Forum Peak, where it typically forms the only solid rock on the entire route. Considering its advanced age it is still in pretty good shape.

Park policy does not encourage technical climbing, because of unreliable rock, and anyone considering steeper routes on these peaks should check their life insurance policy.

Access to Waterton Park is via Highway 6 from Pincher Creek, some 48 km north, and by Highway 5 connecting to Cardston, 45 km east. The famous Chief Mountain Highway provides access from the US but is open in summer only. Located in Waterton Park is 16 km Akamina Parkway, beginning right in the townsite and terminating at Cameron Lake. Red Rock Canyon Road, 15 km in length, starts a few kilometres to the northeast.

Facilities in Waterton are just what you would expect in a tourist-oriented town. From about mid-May to late September, you can probably find most anything needed in the way of groceries, service stations, restaurants, camping and hiking supplies, souvenirs and ice cream. Everything is within convenient walking distance downtown. Visitors require a national park permit and this can be purchased at the entrance gate. When you tire of tramping around the mountains, scenic boat trips on the lake are popular and there are horse rides on offer too. Mountain bikes and pedal carts are available in town for the mildly adventurous.

Accommodation Several campsites are found nearby, both in and outside the park. Within the park, showers are available at the townsite campground only. When the thrill of camping wears off, local hotels, motels, chalets and motor inns will be happy to take your money.

The Parks Information building is found just before the town centre, across from the majestic Prince of Wales Hotel, a historic Waterton landmark on the open shores of the lake.

Info Centre (seasonal) 403-859-5133

Wardens are happy to provide advice on current mountain conditions, weather forecasts and tips to keep you out of trouble in your pursuits. Just ask. The warden office and maintenance compound are west of the golf course on the right-hand side as you drive into town.

Difficulty: Difficult scrambling for a short distance via southwest aspect

Round-trip time: 3.5–7 hours

Height gain: 960 m

Maps: 82 H/4 Waterton Lakes; Gem Trek Waterton Lakes

As you drive north toward Redrock Canyon, it is hard to miss Mount Galwey. Rolling, verdant hills beginning at road’s edge lead to stark, dry slopes crowned by a blunt-arrowhead summit. The very shape begs investigation, and judging by register entries, many do just that – repeatedly. It is easier than the view suggests. Try from late May on.

Follow Redrock Canyon Road in Waterton National Park 7.8 km and park at Coppermine Creek picnic area.

Beginning at Coppermine Creek picnic area, follow what begins as a promising trail up undulating hills on the right-hand side of the stream. Stay well above the drainage to avoid a narrow, canyon-like section, and tramp along the rounded crest of the open ridge that leads directly toward Mount Galwey. En route you pass a sizeable outcrop of rich red rock – red argillite of the Appekunny Formation. Where the ridge meets the peak, angle left, crossing above the headwaters of the right-hand (south) fork of Coppermine Creek. Continue working diagonally up and left, circling the peak in a clockwise direction. Now you are above a scree basin feeding the north fork of Coppermine Creek. Galwey’s defences are weaker on this side.

Although the strata are downsloping and rubbly as you plod around, this unstable terrain improves as you reach the steeper sections. A key landmark to watch for, unless it topples one day, is a rock pinnacle capped by a much larger rock poised against the skyline. It resembles a mushroom: a very big mushroom. Some distance below it, a gully breaks the first steep rock band, steering you toward vertical blocks stained yellow with lichen. Ascend this gully. This chute narrows as you climb through a wonderfully solid band of black igneous rock which, according to Keith Dewing of Natural Resources Canada, is Purcell sill. This stretch is the best rock on the whole ascent; too bad there is so little.

As you emerge on a level platform, possibilities look few. Now you are higher than the point where a north-trending ridge abuts the summit mass of the peak. Although it looks exposed, the correct way lies southward past a rock “wing” projecting airily over the abyss. There really isn’t a sheer drop, but merely a sloping scree bay a few metres below. Traverse into it on small but solid ledges – the crux. Now you are onto a more southerly aspect and almost up. Just off to the right, a rectangular window through a solid wall of rock frames a view of prairies lying east. Follow the path of least resistance and scramble easily up to the flat summit. Although the north end is higher, this south end is Mount Galwey and is shown as the summit on all maps.

Mount Galwey is named for Lieutenant Galwey, an astronomer with the BBC – not the broadcasting network, but the British Boundary Commission.

Topo maps show the name applied to the south summit, but they also show the north peak being a bit higher, which a few people have pointed out to me over the years. If you can stand yet more rubble, one way to reach the north peak is as follows.

Ascend as for Mount Galwey’s south peak, up the first steep bit but not the second one. From there, traverse left (north) on the ledge system between the two steep rock bands. There is no advantage to gaining the actual ridge crest between the two summits. Cross several broad gullies and watch for a spot to scramble up the steep band above you – there aren’t many choices. Continue traversing to the gully directly below the north summit and adjacent to the left skyline ridge of the peak. Head straight up, encountering only moderate scrambling depending on your particular route. At the summit bump, go around to the far left (north) end. Allow about an hour each way, much of it tedious sidehill gouging. It is also feasible to make a loop by following the connecting ridge from North Galwey back out to the road. Stay to the left of and below the steep part of the ridge. Moderate at most.

Telephoto view of Mount Galwey ascent.

The approximate traverse route to North Galwey between the two steep bands as seen from Mount Galwey. Other variations are also possible.

Difficulty: Difficult scrambling via Bear’s Hump; moderate via Tick Ridge

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 1040 m

Maps: 82 H/4 Waterton Lakes; Gem Trek Waterton Lakes

Mount Crandell offers an opportunity to scramble up a small summit on the very doorstep of Waterton townsite. Three different routes, discussed in decreasing order of difficulty, can be readily combined to effect a traverse. Despite a radio repeater on top, the ascent is worth doing. Try from May on.

Depending on your choice of route, access is either from Bear’s Hump, behind the Waterton Park tourist information booth, or from the park warden’s office, 5 km east of the townsite.

Most demanding of the three described routes is an ascent from Bear’s Hump. Starting from the tourist information booth, follow the signed path that fizzles to scratchings of an animal trail shortly beyond Bear’s Hump. Continue directly up to the first steep wall. Here the route suddenly takes on a serious nature. For the next couple of hundred vertical metres, you must work your way left on ledges – many of which are treed to some extent – and search for weaknesses that allow you to ascend successive cliff bands. The rock is solid but often smooth. It is impossible to even attempt to describe an exact line, as possibilities are many and the best line depends largely on your skill at routefinding. In critical spots you’ll see paths made by streetwise bighorn sheep who eventually tire of panhandling around town and come here to get away from it all. When these paths do appear, it is often worth following them. Sheep are no fools: despite superb climbing skills, they often choose the easiest available line.

After surmounting several rock bands, you emerge onto easier terrain within a huge bowl that acts as a collecting basin for waterfalls cascading toward Akamina Parkway. The skyline ridge on your right is a narrow and challenging continuation of the ascent. Coincidentally, Tick Ridge, beginning near the warden office, intersects at this point.

You can either scramble on the crest of this airy cockscomb or, easier, wander and scramble along the foot of it on the left (west) side to avoid the most tenuous bits. At some point, though, you will find the crest preferable to traversing alongside. By then difficulties on the ridge will be much less daunting. Challenges diminish as you approach the summit, and the last stretch is just a walk. Owing to the degree of routefinding required, this particular ascent line would present significant challenges as a means of descent. I cannot recommend it for that purpose. Similarly, until you top out there is no quick way off. Gullies end in cliffs. The usual descent route is described last.

The most popular ascent line starts close to the park warden office and maintenance compound. It is obvious and readily studied from the highway.

Walk uphill through the grassy meadow just north of the warden’s parking lot, aiming for the bottom of the big southeast-facing drainage gully where a stream flows. The ridge rising diagonally to the left offers a no-nonsense line of ascent and requires only minor detours into trees to overcome a couple of steeper steps. It then joins the cockscomb described earlier under the Bear’s Hump approach.

The easiest route, used most frequently for a quick descent, uses open slopes on the right (north) side of this same southeast-facing drainage gully emerging slightly north of the warden office.

From the summit, drop down through larch forest, angling left as you lose elevation. Keep left of the main drainage system, which becomes better defined as you descend. Do not follow the creek down into narrow confines. Instead, stay well above it on open slopes to the left, going overtop a jutting promontory, easily seen from the road. Scramble down the path of least resistance, aiming roughly for the stream’s exit into the meadow below. Heavy rains in 1995 widened the streambed, so you may be able to avoid the bush more easily now. Total descent time may well be less than an hour.

Mount Crandell is named for Calgary businessman Edward Henry Crandell, who had been drawn to the short-lived oil seep “Discovery Well,” on Cameron Creek, identified today by a roadside monument.

Mount Crandell as seen from Waterton Lake, showing approximate ascent line from Bear’s Hump. B: Bear’s Hump; T: Tick Ridge; D: descent.

Mount Crandell as seen from the road. T: Tick Ridge; D: descent route.

Tick Ridge route on Mount Crandell.

Difficulty: Easy to moderate scrambling depending on route

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 1150 m

Maps: 82 H/4 Waterton Lakes; Gem Trek Waterton Lakes

Bertha Lake is a popular and busy day hike from Waterton townsite, but one way to escape the lakeshore masses is to make an ascent of nearby Bertha Peak. There are two routes, both of which start right from the lake. One of them is little more than a hike. From the summit you can glimpse big peaks in Glacier National Park. Early season ascents may require an ice axe; try from mid-June on.

Drive into the Waterton townsite, past the information centre and along Evergreen Avenue across from the campground. Continue past Cameron Falls to where a gravel side road leads to the signed trailhead for Bertha Lake in a small parking area on the right among cottages.

From the parking area, follow the signed Bertha Lake trail (note the cut-off at 1.5 km) reaching the lake in about 1.5 hours. The objective sits directly across the lake and is evident when you arrive. The two routes begin on either side of the obvious waterfall above the campground. The easier track is the one to the left of the falls and at first rises diagonally leftward along the base of a large rock outcropping. When this ends you angle back to the right. Open ground then takes you upward to a stand of larch trees and a high point. Lose a slight bit of elevation as you head over towards the summit ridge, which is now in view. The remainder of the ascent to the top is merely a pleasant amble over rock plates covered with lichen. The biggest challenge may be to deal with the oft-present Waterton winds.

In previous editions, I only described the gullies route, which has a bit more challenge. This trail (which is not difficult scrambling) follows a drainage up to easy-angled terrain lying to the right of the waterfalls. On the way up, small waterworn gullies are usually solid, making for acceptable scrambling, and are preferable to steeper rock that is often loose. There are many possibilities here, all of which converge for a final trudge up scree before reaching the summit ridge.

The summit gives a clear view down to Bertha Lake and of the switchbacks that lead up from it, as well as impressively larger mountains in Glacier National Park that punctuate the southern horizon. The dominant adjacent peak to the southwest is Mount Alderson, ascended from Cameron Lake on Akamina Parkway.

For a longer day, it is possible from the summit to continue along the ridge circling around the basin and then descend rubble slopes back to the lake. Apparently the scrambling is not difficult and only minimal routefinding is necessary along the last part of the ridge. The simplest way down from the ridge back to the lake would be located farther to the left of the described easy route up.

And just who was Bertha? She was a counterfeiter who was locked up by folks in Waterton because they didn’t like her type. It seems nobody minded her name, though, and it persists to this day.

Bertha Peak and two ascent routes from slopes above the lake. The easier route is to the left of waterfalls; the gullies route is to the right.

Difficulty: Easy

Round-trip time: 4–6 hours

Height gain: 970 m

Maps: 82 G/1 Sage Creek; Gem Trek Waterton Lakes

Though more of a plod than a scramble, Mount Carthew is sometimes ascended by day-trippers hiking the Carthew–Alderson trail or as a destination in itself. The ascent is a minor but worthwhile diversion from the trail. From the top you can wistfully study more impressive summits in nearby Glacier Park, and a choice of two routes up offers variety. Try from late June on.

From Waterton townsite, follow Akamina Parkway about 16 km to Cameron Lake. The Carthew trail begins on a boardwalk to the left, near the canoe concession.

Follow the wide trail as it rises in a series of switchbacks through deep forest, then eases off to reach the shore of pristine Summit Lake in about an hour. Most parties continue past this pond to the high point of the Carthew–Alderson traverse, a saddle between those peaks. Although called Carthew summit, it would be better described as Carthew–Alderson Pass or col. Regardless, a simple hike up scree on the left leads to the ridge and summit 290 m above.

Waterton Park warden Edwin Knox showed me a more enjoyable off-trail variation that I will share, but please don’t trample the vegetation. Gain Mount Carthew’s southwest ridge at a point about 10 minutes past Summit Lake. Angle leftward up the hillside through open forest. Once you’re on the wide ridge, expect no particular difficulties en route to the top. Partway up you will ascend a small boulder field, above which are two precarious rock “stacks” on the skyline. After a short 10 m descent to the ridge, the view continues to improve. Cameron Lake and mounts Chapman and Custer to the south vie for attention. Just before the summit, the normal route from the Carthew trail merges. As a descent route, it is quick and dirty – especially if you fall down.

The summit is a prime example of a locally widespread rock called red argillite. This is pretty much the same stuff as at Red Rock Canyon, except you can drive there. Without the presence of oxygen eons ago, this once iron-rich rock wouldn’t have rusted, and red argillite would instead be green argillite.

Below the summit are three Carthew Lakes occupying successively lower bowls. Such lakes are called “paternoster” lakes. As you look southeast, the summit of Mount Alderson’s west ridge is obviously straightforward from the hiking trail, and obsessive folks may decide to head up there next.

The best scenery undoubtedly lies to the south and west in Glacier Park, where mounts Chapman and Custer provide the backdrop for Nooney and Wurdeman lakes. Immediately west of Cameron Lake lies broad, undulating Akamina Ridge, a worthwhile ridgewalk described in this section.

Returning to the hiking trail, you can either go back to Cameron Lake (shorter) or extend your day by continuing the hike past Alderson Lake and eventually reach Waterton townsite. Allow at least 3 hours from top to town. Note: A hiker’s shuttle travels to Cameron Lake each morning. Check at the information centre near the Prince of Wales hotel.

Difficulty: Hard scrambling

Time: 1–1.5 hours from Mount Carthew; several hours to continue to townsite

You can continue north from Mount Carthew to Buchanan Peak, but it is harder and less pleasant than ascending Mount Carthew. Though initially easy, the descent to the col gets more serious at two successively steeper bands of rock. Waterton has little rock that is solid enough to form cliffs, and where it does, the cliffs are usually rubble-strewn and loose. Here is no exception. Know your ability and use great care with all handholds. Work downward to the left to less steep cliffs and find a feasible spot to downclimb to scree. Unlike Mount Carthew, Buchanan is not simply a hike, but with care, experienced scramblers can reach the intervening col and the next high point (1 hour). A lesser point on the SSE ridge is the actual summit as shown on maps.

On descent, you can follow the ridge that extends southeast toward Alderson Lake. Keeping some distance below the crest is preferable. Where possible, use bighorn sheep trails: the animals know the way. Depending on your route, about a third of the way down you may encounter short, awkward descents on downsloping rock. The remainder is easier and continues right down to the farthest end of the ridge to meet the hiking trail below. If hiking up from town, allow 3–4 hours to the top.

Doing both peaks will occupy a full day, and from here it would make little sense to hike back up past Carthew Lakes to reach Cameron Lake. You might as well hike downhill to town. Just remember, if your car is at Cameron Lake, it is about 18 km away from where you’ll finish in town. That shuttle service makes a lot more sense now, doesn’t it?

View of the straightforward hike up Mount Carthew. L: ledges shortcut route; SW: southwest ridge; S: summit.

Difficulty: Easy; minimal scrambling

Round-trip time: 6–9 hours

Height gain: 1030 m

Maps: 82 H/4 Waterton Lakes; Gem Trek Waterton Lakes

Mount Alderson is the other popular peakbagger’s objective on the Carthew–Alderson trail, Mount Carthew being the first. Although it is little more than a hike, it ranks as a fine viewpoint and probably sees less traffic than its counterpart does. Try from late June on.

Begin from Cameron Lake as for Mount Carthew and hike past Summit Lake to the high point on Carthew’s south shoulder (2 hours). Lose about 50 m as you descend to the saddle near upper Carthew Lake. Then simply ascend the reddish slope to the ridge undulating eastward and reach the summit of Mount Alderson. Allow 1–2 hours from the low point.

The view to the bigger summits in Glacier National Park is an inspiring companion to your trek. Most Waterton Park area peaks are small in stature and the scene Mother Nature has painted here is pastoral. Gentle hues of red and green argillite above treeline, deep blue lakes and sky (if you’re lucky) and golden prairies to the east impart a feeling of serenity. Often, though, the wind conspires to keep you on your toes (or blow you off them!) rather than let you dreamily wander in an elevated, euphoric daze.

Although most of the ascent is merely hiking, two steps in the ridge require short descents. The first, on good rock, is easily descended on the left side; the second step is better turned by scrambling down a succession of downsloping, shaley ledges on the right. No further problems are encountered. The return is via the same way.

According to Over 2000 Place Names of Alberta, by Holmgren and Holmgren, Lieutenant General E.A. Alderson commanded the Canadian Expeditionary Force in France in 1915–16.

The colourful and gentle ascent ridge of Mount Alderson as seen from the lower slopes of Mount Carthew. The high peak at upper right is Mount Cleveland.

A September dusting of snow highlights the peaks of Glacier National Park as seen from the summit of Mount Alderson. MCl: Mount Cleveland; CP: Chapman Peak; MP: Mount Peabody; MCs: Mount Custer; KtP: Kintla Peak; KnP: Kinnerly Peak; LKP: Long Knife Peak; KEP: King Edward Peak; SP: Starvation Peak. Photo: Vern Dewit

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling

Round-trip time: 6–10 hours

Height gain: 1410 m

Maps: 82 G/1 Sage Creek; Gem Trek Waterton Lakes

Ease of both approach and ascent has established Waterton’s highest point as a most popular scramble. A well-graded approach trail leads to steep but direct rubble slopes guaranteed to have the fittest people puffing to the top. Energetic parties can take an enjoyable traverse to include mounts Hawkins and Lineham. Carry an ice axe for any remaining snow patches. Try from mid-June on.

From Waterton townsite, follow Akamina Parkway 9 km to Lineham Falls trailhead, on the north side of the road. Note: The upper part of the ascent route is visible from Rowe Lakes trailhead, 1.3 km farther down the highway.

Follow the wide, well-graded Lineham Falls trail as it switchbacks onto luxuriant, grassy slopes and then seeks the depths of sombre forest. In an hour, you suddenly escape shady coniferous forest and are greeted with the first view of Lineham Creek as it cascades dramatically over a vertical headwall. More importantly, though, this clearing you have entered is an avalanche run-out zone from Mount Blakiston and is the usual line of ascent. Look for bits of a trail along the right side of the drainage.

A search for difficulties reveals only brief rock steps, and the angle of the terrain seems modest. Left of the highest point, the guard band of dark, castellated cliffs has eroded to allow easy passage to the ridge. Most rock steps between seem surmountable in perhaps as little as a single bound. By comparison, when seen from nearby Mount Lineham, this route appears discouragingly long and incredibly steep. The truth, however, lies somewhere between those two perceptions.

Follow the faint trail along the right side of the gully. Stunted evergreens, defying yearly avalanches, huddle precariously in the lee of the first bluffs you approach. In June it may be feasible to go up consolidated remnants of climax avalanches, but to do this you will definitely need an ice axe. Eventually the angle steepens, and if snowy you will probably prefer to ascend nearby talus instead.

Although Mount Lineham obstructs much scenery initially, peaks in nearby Glacier Park and in BC emerge on the horizon as you progress, step by tedious step. As you draw closer to the final rock band, watch for a couloir directly under summit cliffs. It starts at the first weakness to the left of the east face drop-off. Aim for a huge block of rock against the right-hand skyline; the couloir just left of this is the preferred finish. Grovel up exasperatingly loose scree to red argillite supporting these black cliffs of Purcell sill, where fluorescent yellow lichen adorn the walls. The rock is wonderfully firm, but the scrambling ends all too soon.

Little distance separates prairie from peak in Waterton, allowing the eye to roam freely between eroded summits and rolling grasslands to the east. Cameron Lake is visible to the south, and beyond, mightier peaks in Glacier National Park reach skyward. Barely visible is the broad Flathead Basin farther west.

To descend, avoid the summit cliffs by walking a short way down the ridge, turn left and return the same way. Lower down, there can be good glissading early in the season, although some stretches are too steep, while others end abruptly on rock. Carry an ice axe and know how to properly self-arrest. Park wardens have not forgotten a past incident on this mountain where a glissade into rocks resulted in a broken bone.

One other hazard for persons ascending snow slopes is the possibility of breaking through snow weakened by water flowing down underlying rock steps. If snow depth is significant, there may be no evidence that such rock steps even exist – until you fall in. This has been responsible for at least one fatality elsewhere in the Rockies.

Mount Blakiston is named for Lieutenant Thomas Blakiston, an explorer and ornithologist who was part of the Palliser Expedition. After a falling out with Palliser he was sent packing, which he did, visiting China, Australia, New Zealand and England before finally settling in the United States.

The deceptively steep-looking ascent route up Mount Blakiston as seen from Mount Lineham. Hawkins Horseshoe continues toward the left of picture. PHOTO: BOB SPIRKO

Mount Blakiston, Lineham Lakes and part of the Hawkins Horseshoe from Mount Lineham.

Difficulty: Moderate scrambling

Round-trip time: 9–12 hours

Height gain: approximately 1850 m

From Mount Blakiston, ambitious parties can make a delightful, albeit long, traverse in a grand horseshoe circling Lineham Lakes basin to bag mounts Hawkins and Lineham, then exit via Rowe Lakes trail. There is much to view, problems are few and you’ll need just one vehicle, not two.

From Mount Blakiston, follow the summit ridge west as it descends gently, jogs southwest, rises to a high point, then heads west over to the bump called Mount Hawkins. Underfoot, in spite of notorious Waterton winds, small grassy patches and pincushion-like clumps of purple moss campion cling to the shale in the hollows.

From Mount Hawkins, the broad ridge continues, curving south to meet the popular Tamarack trail, identified by short metal poles driven into the shale. Again the ridge undulates as it heads east for the summit of Mount Lineham. While this traverse does have a propensity for needlessly losing and regaining elevation, no difficulties are encountered in completing the entire horseshoe. Much of it is wonderful, wide-open hiking, with five Lineham Lakes competing for camera time against a skyline of summits all around. Note: You cannot shortcut through Lineham Basin to Lineham Falls trail. The Lineham Falls headwall is a tricky technical climb and is not recommended for scramblers.

From Mount Lineham, descend south-facing slopes to Rowe Lakes trail. Turn left and reach the road in about 40 minutes. Lineham Falls trailhead is 1.3 km from Rowe Lakes trailhead.

Difficulty: An easy ascent

Round-trip time: 4–7 hours

Height gain: 1100 m

Maps: 82 G/1 Sage Creek; Gem Trek Waterton Lakes

Mount Lineham’s south aspect presents little more than a steep walk, although many hikers trudge to the top by the more circuitous Tamarack trail to west ridge approach. The summit gives a fine view of Mount Blakiston and the Hawkins Horseshoe traverse, which finishes here. In early season, snow-covered south slopes are the perfect angle for practising self-arrest, and glissading conditions can be tremendous then, too. Try from about June on.

From Waterton townsite, follow Akamina Highway 10.4 km to the Rowe Lakes–Tamarack trailhead on the north side of the road. Park here.

Hike Rowe Lakes trail for about an hour to the first open avalanche slope. If you reach a Lower Rowe Lakes trail sign you have gone about 200 paces too far. At the right-hand edge of this avalanche slope, notice a small clearing; this is a good place to head upward, because the rest of the slope has much debris brought down by an avalanche in 2014. Be sure to make plenty of noise as you wander up through the vegetation, as grizzlies feed on a variety of plants that flourish on avalanche slopes like these. Once through the greenery, the rest is a walk-up but you’ll be grovelling on hands and knees in places. For those descending this route, it starts a bit east of the cairn. Cone-shaped Chief Mountain rises above many scree slopes to the southeast and is of special interest to geologists. It was the leading edge of a once-massive 6.5-km-thick wall of rock extending hundreds of kilometres north to Mount Kidd in Kananaskis. Pushed northeast as a largely continuous sheet, it travelled a horizontal distance of some 70 km or so. Geologists, always anxious to find faults, did not let this event slip by unnoticed. They called this the Lewis Thrust, and although similar incidents have occurred elsewhere in the world, few can rival this big push in sheer size. In normal mountain-building circumstances, the oldest rock would lie at the bottom of the heap, but when such faulting occurs, older rock rides up onto younger, thereby reversing the usual sequence. Because of this occurrence 80 million years ago, part of what would have been BC rests in Alberta instead.

An alternative and scenic but longer descent uses part of the Tamarack trail. This loop gives you a view of Lineham Lakes basin that you don’t see from the south slopes. From the top, wander down the often windy west ridge and join the Tamarack trail that descends left into the valley. Pass the Rowe Lakes cutoff and continue back to your vehicle. It is 8.5 km from the Lineham Ridge–Tamarack junction to the parking lot. This option is straightforward, but does make for a more complete and longer day whether you choose it for ascent or descent.

Mount Lineham commemorates John Lineham, a transplanted Englishman and notable Alberta pioneer largely credited with establishing the town of Okotoks. His ventures and adventures included freighting, oil, a lumber mill or two and politics. Excepting oil exploration in Waterton, he tended to be successful in all his undertakings.

Mount Lineham routes as seen from lower slopes of Mount Rowe. South slope route leaves Rowe Lakes trail at obvious clearing at right-hand edge of slope. W: west ridge route; S: south slopes.

Difficulty: Easy with one moderate step

Round-trip time: 6+ hours to traverse

Height gain: 1140 m total

Maps: 82 G/1 Sage Creek; Gem Trek Waterton Lakes

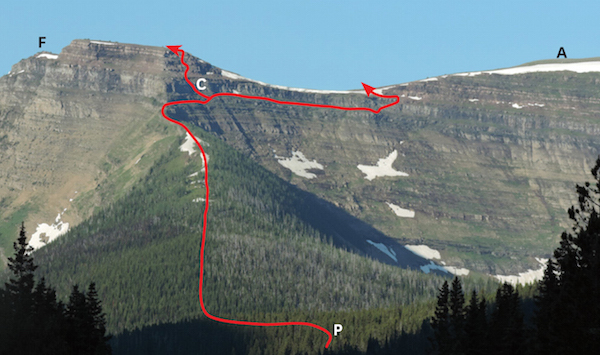

Two moderate scramble routes lead up to a wonderful high traverse of Akamina Ridge, which starts and ends in Alberta but wanders through British Columbia en route. The trip reveals high, glaciated peaks in Glacier National Park not otherwise visible. If visiting Forum Peak, a small bump at the intersection of the Alberta, BC and Montana borders, then the boundary cutline approach is the most direct route. Try this trip from late June on.

From Waterton townsite drive 14 km along Akamina Parkway to Akamina Pass trailhead.

Hike up the trail and reach Akamina Pass in about half an hour. This pass marks the Alberta–BC boundary and you will notice a definite cutline indicating it. Follow this cutline left (south). As of 2014 the bushwhacking along this route was quite easy, although in wet conditions you would get soaked. I encountered only one stretch that had several downed trees despite not having been cleared for ages. Wildlife takes this route regularly and the feasibility of hiking it will be evident by just how well used the animal trail along it appears to be. This cutline approach loses a slight amount of elevation at first, then climbs steeply as it heads for open stands of alpine larch and treeline.

Once you are out of the forest, head straight up the ridge. This ridge could also be reached from a number of spots along the left side of Forum Lake, depending on your preference for trees, shale or rubble. Once you reach the point where the ridge abuts steep rock bands, traverse right 75–100 m. You should find a relatively well-used break where the cliff is not as high and you can scramble up ledges. The first few metres are the steepest but difficulties are only at the high end of moderate scrambling. An impressively tall cairn not far from where you top out indicates Forum Peak, although the exact intersection of the boundaries is about 400 m southeast along the ridge leading toward Mount Custer. Allow 2–3 hours from the trailhead to Forum Peak.

If scrambling the rock band in the usual place proves daunting, you can continue traversing this same broad ledge to an easier spot frequented by sheep and goats which is above the back of the lake. This will be past the obvious point where a buttress of the cliff band cliff band juts out at 139320. Once around the corner of that (it looks exposed but isn’t really), continue along and you should find bits of animal trail heading up eroded brown shale to the low point of the saddle above. It is marked by a cairn where it emerges, should anyone care to descend it, and involves a bit of moderate scrambling only. From this saddle, Forum Peak is nearby on your left (east) and much higher Akamina Ridge is off to the right (west).

Hike to Forum Lake and continue on the trail past the lake. The trail switchbacks up the flowery hillside, aiming for the long ridge that separates Wall and Forum lakes. Near treeline a rock band requires steep, dirty scrambling over a band of large blocks. While this is moderate scrambling at most, hiking parties I encountered mentioned their relief at not having to descend those same rock steps. A slip would result in a tumble down green slopes, flattening flora and frightening fauna, so scout around to find the easiest place to ascend. When you have overcome that crux, open slopes coax you onward. Once you get high enough to glance over toward Forum Peak, it will resemble nothing more than a bump.

Akamina Ridge has a beaten path along the crest but on a windy Waterton day this trail can be more exciting than expected. The route is straightforward as you ascend scree to the high point at 117323, a fine spot to lunch and admire the panorama. Near the far (north) end of Akamina Ridge, watch for a good trail cutting sharply back to the right (east) through open forest and hillsides of Indian paintbrush. This route roughly follows a small drainage down to Wall Lake, where it is signed “Bennett Pass/North Kintla Creek.” Snow may persist well into July on this trail.

Upon reaching Wall Lake you’ll feel much closer to civilization, as it is popular with hikers, campers and fishermen. Continue along the left (west) shore of the lake, then out to the main valley trail, where you turn right to return to Akamina Pass. Allow an easy hour and a half. The entire trip via the cutline approach is some 20 km and is only slightly shorter via the Forum Lake approach.

According to Jack Holterman’s Place Names of Glacier/Waterton National Parks, “Akamina” means “benchland” in the Kootenai Indian dialect. Akamina–Kishinena became a BC provincial park in 1995.

Routes through the rock band to Forum Peak and Akamina Ridge as seen from the road. P: Akamina Pass; C: crux; F: Forum Peak; A: Akamina Ridge.