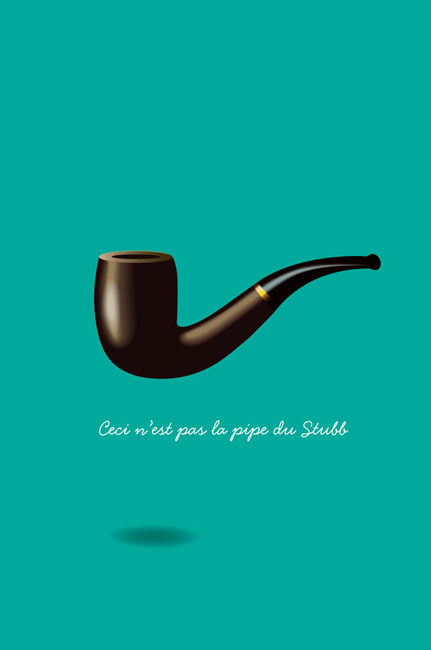

When we read about something—a place, a person—we separate it from the mass of entities that surround it. We distinguish it. We excise it from the undifferentiated. Think of Stubb’s pipe. Or Achilles’s shield. (This thing is different from all other things: this thing is not Ahab’s peg leg, or Hector’s helmet.) We then form some kind of mental representation of it. It is a pipe: like this, and not like that. We form representations, so we can remember, and manipulate the memory of this pipe, so the information can be reused. This representation is a model of some sort. So we readers are also model builders.

Jean Piaget tells us that thought is “mental representation.”

But what kind of representation? Codes? Symbols? Words? Propositions? Pictures?

***

What are we modeling when we make mental representations of literary characters? Souls?

I continue to interrogate readers … I ask them to describe a central fictional character (making sure to only discuss books they’ve just recently finished reading, or have reread several times, so that whatever imagery they conjured when reading would still be fresh in their minds). My subjects respond by offering up one or two physical characteristics of a character (for instance, “He’s short and bald—I know that much”), followed by a longer disquisition on the character’s persona (“He’s a coward, unfulfilled, regretful,” et cetera). I generally have to stop them at some point in order to remind them that I was asking only for physical description.

That is to say, we confuse what a character looks like with who a character, putatively, is.

In this way we are backward phrenologists, we readers. We extrapolate physiques from minds.

***

“A great nose may be an index of a great soul.”

—Edmond Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac

Buck Mulligan (remember him? He is the character who appears at the opening of Joyce’s Ulysses)…

Other things we know about him…

He is, variously:

“Equine” faced; “sullen” of jowl; “strong” and “well-knit”; light haired; white-toothed; “smokeblue” eyed; “Impatient”; older than his occasional flush makes him appear; gowned; waist-coated; panama-hatted; frowning; “wheedling”; “coarsely vigorous”; “broadly smiling”; “erect”; “ribald”; “solemn as a dean”; “heavy”; “gleeful”; “pious”; “grave”; full of “honeyed malice …”

None of these descriptors helps me to picture Buck (some of them seem downright contradictory: his being “plump” and his “equine” face, for instance).

And these depictions of Buck could portray practically anyone. But it is Buck’s introductory epithet—stately, plump—that defines him. But not as a picture. That description becomes, for me, a designation of type.

(This “stately” and this “plump” are like categories, in that they don’t describe so much as they characterize.)

The novel is, among other things, a typology…

I notice that we don’t praise the descriptive richness of fables (in direct contrast to what many readers find commendable in novels and stories). Here, characters are the transparently generalized types.

The flatness of characters and settings in fables and parables—their purposefully two-dimensional, cartoonish aspect—allows such literary systems to function properly. What is important in these cases is universal applicability—as opposed to, say, psychological detail. This is true to the extent that we readers, when we read such tales, might become: a fox; a hawk; a grasshopper; a satyr; a stag.

(In fables, the stylized visual aspect of the players and settings is obvious to us. Yet even the most psychologically rich characters and lushly described locales in naturalistic fiction are, visually: flat.)

Are all characters, in all types of fiction, merely visual types, examplars of particular categories—sizes; body shapes; hair colors …?

This doesn’t feel true to me as I’m reading a novel. Good characters feel unique. But this uniqueness is only a psychological uniqueness. As I’ve mentioned many times, authors relinquish little information concerning a character’s appearance—thus it’s hard to imagine these characters as visually unique, one from the next. It’s hard to imagine them aquiring visual depth.

Yet somehow they seem to.

“The ‘Redskinnery’ was what really mattered … take away the feathers, the high cheek-bones, the whiskered trousers, substitute a pistol for a tomahawk, and what would be left? For I wanted not the momentary suspense but that whole world to which it belonged—the snow and the snow-shoes, beavers and canoes, warpaths and wigwams, and Hiawatha names.”

—C. S. Lewis, On Stories

And how does a character or setting acquire this seeming depth? How does a verbal construction become felt?

How do they emerge as complete in our minds? How do they become, visually