10.

The One Piece I Couldn’t Live Without!

The big news this morning is that there’s going to be an election. But the even bigger news in this house is that my wife is a lying, scheming cheat – although I’m saying that as someone who’s slept with her sister and most of her friends over the years.

I walk into the kitchen. She’s feeding Hillary mashed-up something or other while Fionn’s shaking a little rattle at him and going, ‘Buenos días, Hillary! ¿Cómo estás?’

They both turn and look at me at the exact same time. Sorcha looks terrible. I’m pretty sure she got zero sleep last night because every time I woke, I could hear sobbing in the bed next to me.

She goes, ‘Ross, will you have some breakfast?’

And I’m there, ‘I’m not hungry,’ which is total horseshit. But then, it’s so rare for me to find myself in a position where I’m not the actual bad goy that I decide to milk it for all it’s worth.

Sorcha goes, ‘Ross, I’m so sorry.’

And I’m there, ‘Yeah, no, so you said. I’ll have some French toast with bacon if it’ll make you feel any better. And a pot of coffee if you’re looking to take your mind off what you did to me.’

Fionn snorts – he actually snorts? ‘Yeah,’ he goes, ‘you’re really milking this, aren’t you, Ross?’

And I’m there, ‘How would you like it if I put Hillary on a plane and sent him to the other side of the world?’

He doesn’t answer me. The back door suddenly opens and in her old man walks. He’s all, ‘You’ve seen the news, I take it? Micheál Martin says there’s no way he’s going to be bullied into releasing his Leaving Cert results and Leo Varadkar is going to the Park this morning to ask the President to dissolve the Dáil.’

Sorcha goes, ‘Dad, I’ve got more important things on my mind this morning.’

He’s like, ‘More important than the future of your political career?’ Then he looks at me. ‘And what happened to your intervention? Weren’t you supposed to tell the world that your father and his Russian friends were behind all of this?’

I’m there, ‘I did the interview. They just decided not to run with it.’

Sorcha goes, ‘Croía and Muirgheal actually want there to be an election? Oscail do bhéal, Hillary. Maith an buachaill! They think women could do very well in it.’

His face lights up. He goes, ‘There’s the answer! You’ve got to run, Dorling! We always said we’d treat your time in Seanad Éireann as an apprenticeship before having a second run at a Dáil seat! We might even think about Dún Laoghaire this time!’

‘Dad,’ Sorcha goes, ‘I’m not sure it’s what I want any more.’

‘Well, you’d better make up your mind. They’re saying it’s likely to be a very short election campaign.’

‘Dad, you’re not listening to me. I think I need to step away from politics to spend more time with my family.’

She smiles at me, waiting for my approval. It’s hordly a huge sacrifice. She wasn’t in the place a wet day.

He’s raging with me, of course. He goes, ‘Oh, you think it’s something to smirk about, do you? A brilliant young woman, who could make a difference to the lives of millions of people both here and abroad, is turning her back on politics – and for what?’

The back door opens and in walks Sorcha’s old dear. She goes, ‘One of your sons just called me a shitting ugly focktard.’

I laugh. In a focked-up way, I’ve kind of missed the swearing.

‘So much for that school,’ she goes, ‘that was supposed to unlock their genius.’

It suddenly dawns on Sorcha that they’re not actually there this morning. She goes, ‘Ross –’

And I’m like, ‘Yeah, no, they got expelled. Cords on the table – Sasha said she tried everything, but in the end she just had to accept that she was pissing into the wind with them.’

I look out the window. They’re booting a – yeah, no – soccer ball around the gorden. It looks like we’re back to square one with them.

Sorcha goes, ‘In a way, I’m glad they were expelled. I realize now that I’ve been trying to fix the problems of the world while outsourcing the problem of my own children to Sasha, Erika and whoever else would take them.’

Her old dear goes, ‘You’re not still beating yourself up over sending that girl away, are you? She was out of control!’

Sorcha’s like, ‘She has a name, Mom. It’s, like, Honor?’

For me the questionmork has always been silent.

I’m there, ‘So presumably you’re going to apologize to her?’

Sorcha doesn’t love the sound of that. ‘Apologize to her?’ she goes.

I’m like, ‘Yeah, for accusing her of trying to poison a baby. And you can apologize to her for sending her away as well.’

Sorcha’s old man sticks his ample hooter in then. He goes, ‘Thankfully, she has no idea she was sent away.’

And I’m there, ‘She’s going to – because I’m going to tell her everything.’

Sorcha goes, ‘Ross, please! She’s had the time of her life in Australia! If we tell her that it was a punishment, she’s going to end up hating me even more than she already does!’

I’m actually thinking about this when there’s suddenly a loud crash – the sound of breaking glass – then Sorcha and her old pair scream as a soccer ball comes flying through the window, then bounces across the floor of the kitchen.

Leo looks at us through the broken window. ‘Pack of focking fockpricks!’ he goes.

Fionn’s there, ‘For God’s sake, Hillary could have been hit by that glass! He could have lost an eye!’

And Sorcha’s old man goes, ‘Those three boys are on the same path to ruin as the other one.’

The other one being my daughter. I just decide, that’s it. I’m not listening to this shit any more.

I’m there, ‘Sorcha, you don’t want me to tell Honor the truth, right?’

She goes, ‘I just don’t think it would be helpful in terms of my relationship with her going forward.’

‘Okay, if you want me to keep the truth from her, this is what it’s going to take. Honor’s coming home in, what, three weeks’ time? I want these two focking knobs gone by then.’

I flick my head in the direction of Sorcha’s old pair.

Her old dear goes, ‘How dare you speak about us like that!’

I’m there, ‘I don’t want them in the house. I don’t want them in that shed out there. I want them gone.’

Sorcha’s old man goes, ‘Good luck with that. I expect you’re about to be very disappointed.’

Then I flick my thumb at Fionn and, without even looking at him, I go, ‘Same with him. He’s caused nothing but trouble since he moved in here. I don’t want him here when Honor comes home either.’

He’s there, ‘I’m not moving out.’

I’m like, ‘Dude, you can’t threaten us with protection orders any more. You’ve got fock-all to borgain with. That’s the deal, Sorcha. You either fock these three jokers out of the gaff or I’m telling Honor the full story.’

And Sorcha – without even looking at Fionn or her old pair – goes, ‘Fine, Ross. They’re gone.’

‘Oh my God, Mark Twain – you are such a sexist prick!’

Woke Reads operates out of a room in the basement of Tallant, Gammell and de Paor Solicitors in Merrion Square, where Croía’s old man happens to be a portner.

I tip down the steps and I realize that it’s actually Huguette’s voice I can hear coming through the open window.

She’s like, ‘He says here, “I think I could write a pretty strong argument in favour of female suffrage – but I do not want to do it.”’

I hear gasps from a few people.

Croía’s there, ‘It doesn’t surprise me even a little bit. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for instance, is full of misogyny. And racism. I’m going to put it on the list.’

‘Well, I’m going to tweet this quote,’ Huguette goes. ‘We need to get everything he ever wrote removed from the shelves of our libraries until we can produce, like, clean versions?’

I press the buzzer.

I hear Croía go, ‘Who’s that?’ and then another voice – not hers or Huguette’s – go, ‘Oh my God, it’s a focking man!’

Seriously?

A few seconds later, Croía opens the door with an already angry look on her face. She’s like, ‘Oh, for fock’s sake!’

I’m there, ‘I want to know does the deal still stand?’

‘What deal? What are you talking about?’

‘As in, you telling your niece to get off my son’s case.’

‘I can’t tell Huguette to do anything.’

‘Can you ask her, then?’

She goes, ‘Why don’t you ask her yourself?’ and she opens the door to let me in.

It’s a pretty poky office with, like, six or seven desks, each with a – not sexist – but woman sitting behind it? They all look at me like I’m an alien.

‘I thought this was supposed to be a safe space,’ one of them goes.

I’m like, ‘Don’t worry, I’m not staying.’

I look at Huguette. I’m there, ‘Putting the Students’ Union on my son – that was a nice touch.’

She goes, ‘He shouldn’t be using social media to spread hate messages. He might find women in burqas funny, but to hundreds of millions of women all over the world it’s an instrument of male oppression.’

I’m tempted to comment on that, but I don’t really know what she’s talking about.

Instead, I’m there, ‘I was hoping you might lay off him. Ronan, I mean. Give him a break.’

‘And why would I do that?’ she goes.

‘Because he’s a good person.’

‘He slept with my friend Rachel.’

‘He’s a horny person. I’m not denying that. I could say it takes two to tango and blah, blah, blah. But I won’t. I’m just going to say this. What Ronan has come through in his life, Huguette, is pretty amazing. He was raised by a single mother in – I know you don’t want to hear the word – but Finglas? You wouldn’t believe the disadvantages he’s had to overcome in his life – he got my genes, for fock’s sake. But thankfully he didn’t inherit my brains. You see, he’s super smort, as you already know. And he’s decided to study Law because he wants to use his brains to help the people in the community where he lives – the poor, the vulnerable, the accident-prone. Man or woman, it doesn’t matter a fock. He’s a good goy. And he could make a serious, serious impact on the world as long as you don’t destroy him. Because that power is in your hands.’

The office is just, like, silent. I’d love to think that I’ve got through to them all, except then I hear a woman go, ‘Look, everyone, the white cisgender male is showing he has a heart after all! You woman-hating, Ernest Hemingway asshole!’

But I notice Huguette’s face definitely soften. She looks at Croía and goes, ‘What do you think?’

Croía’s there, ‘I told you, he was happy to give us all that stuff about his dad.’

Huguette looks back at me. ‘Okay, I’ll give him a break.’

I’m there, ‘You mean you won’t put him on trial in September?’

‘We don’t have trials. We have hearings.’

Tell poor Phinneas McPhee that. I don’t say that, though. I’m just like, ‘Thanks, Huguette. I’m, er, pretty grateful to you.’

‘Yeah,’ she goes, ‘like I need your focking gratitude.’

Everyone goes back to work then. ‘Your tweet about Mark Twain,’ one of the women goes, ‘has already got eighty-five Likes and thirty-two retweets, Huguette. Oh my God, someone says that the N-word is mentioned 219 times in Huckleberry Finn! Oh my God! That is, like –! Unless he’s black, of course. Do we know if he’s black?’

‘Mark Twain?’ Croía goes. ‘No, he’s white. He’s also dead.’

‘Right. Because my next question was whether we could call out this racist asshole on Twitter?’

I’m there, ‘I’ll, er, leave you ladies to it,’ and I head for the door. I end up running into Muirgheal on her way in. She’s wearing, like, a white suit, with a humungous blue-and-white rosette – and on it are the words ‘Massey – An Independent Voice for Dublin Bay South’.

She’s there, ‘Is Sorcha running?’ because they were, like, constituency rivals last time? ‘Please tell me she’s not.’

I’m there, ‘No, she’s decided to concentrate on her family.’

‘That’s good. I was going to say it would end up splitting the Independent vote. I always thought she was more suited to Dún Laoghaire anyway. Thanks again for doing the interview.’

‘Hey, I meant every word I said about the wanker. The focking pair of them. My only regret is that you’re not going to end up using it.’

She goes, ‘Oh, don’t worry. Like I said, we’ve got something even better planned for your father,’ and then she looks at Croía. ‘The ropes are going to need to be pretty thick if they’re going to hold him down.’

Okay, that gets my attention.

‘Jesus Christ,’ I go, ‘what are you planning to do with him?’

Croía’s there, ‘We’re going to tie the racist, misogynistic asshole up and throw him in the focking sea.’

I stare at her. She’s actually serious.

I’m there, ‘I’m not sure I one hundred percent agree with that,’ surprised at myself for actually giving a shit?

But then ten seconds later, she laughs and I realize that – yeah, no – she’s not serious after all. She looks at Muirgheal and goes, ‘Will I show him?’

Muirgheal’s there, ‘Why not? He hates him more than we do.’

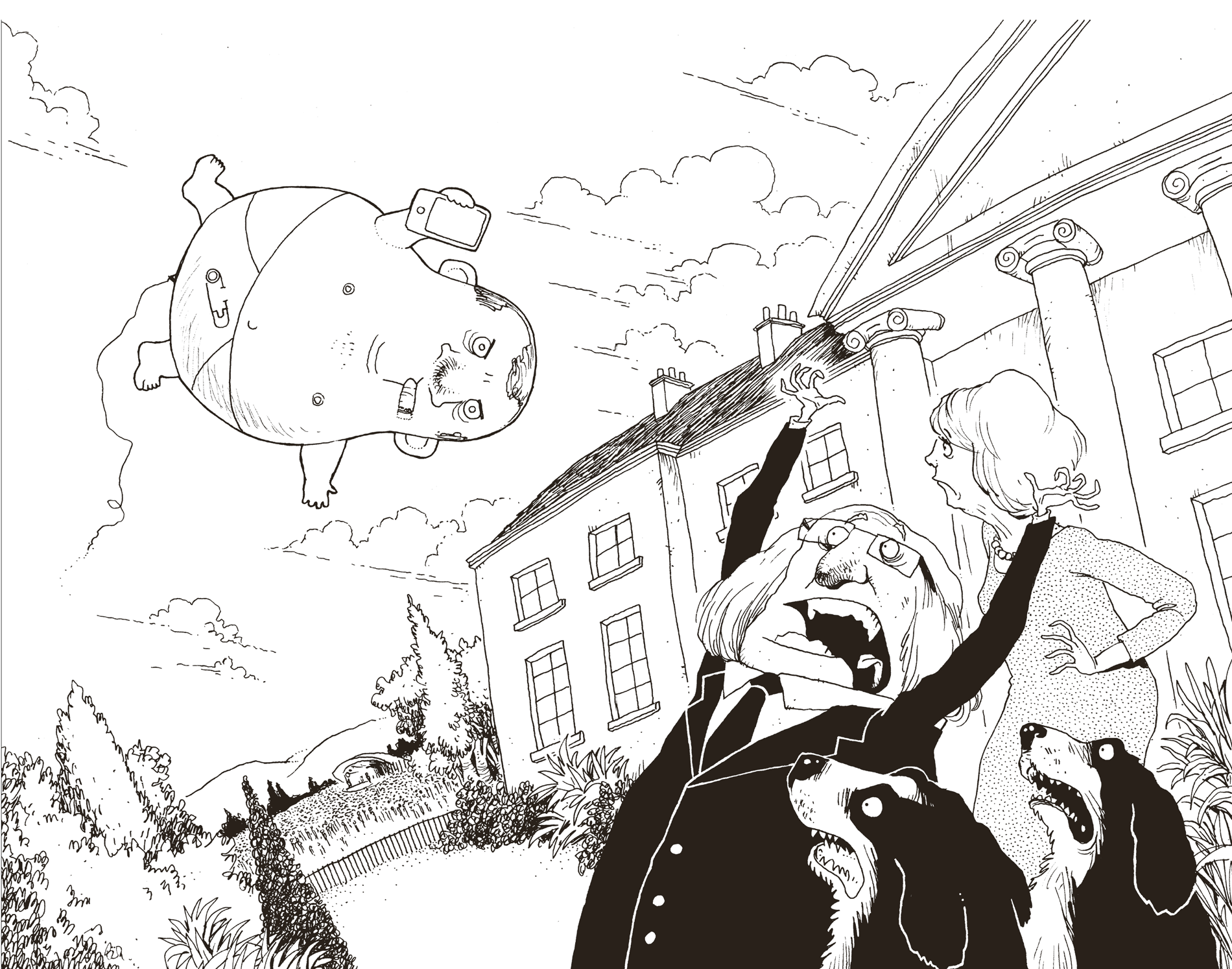

Croía grabs this, like, photograph from her desk – it’s of a giant balloon version of my old man, with a mobile phone in his hand, and he’s naked except for a nappy.

‘It’s the Charles O’Carroll-Kelly Baby Blimp!’ she goes.

And I’m like, ‘Right,’ at the same time wondering what the fock they’re planning to do with it.

Croía obviously reads my mind because she goes, ‘Your dad is having a rally in the Phoenix Pork the Sunday before the election. All his supporters are going to be there.’

I’m there, ‘Er, okay.’

‘And we’re going to launch this in the middle of the pork so that everyone can see it.’

Muirgheal’s there, ‘Oh my God, can you imagine how pissed off he’s going to be when he sees it?’

I look at Muirgheal, then back at Croía.

‘Er, obviously I know fock-all about politics,’ I go, ‘but is this definitely better than telling the world that he’s in league with the Russians?’

And Muirgheal’s there, ‘You’re one hundred percent right, Ross. You know fock-all about politics.’

I ring Ronan but there ends up being no answer, so I leave a message on his voicemail to tell him he has nothing to worry about, that I’ve squared it with Huguette and he can go back to college in a few weeks’ time without having to worry about facing a trial.

I’m there, ‘I hope it hasn’t put you off the idea of playing the field. I’d still hate to see you settling down too young. Especially with someone from that family. Anyway, give me a shout back, will you? We haven’t properly talked in ages.’

I tip downstairs, then into the kitchen I go. Fionn’s in there, feeding little Hillary from a spoon. He’s going, ‘Das ist gut, Hillary! Yum-yum! Ja?’

I’m there, ‘I’m not going to miss that when you finally move out,’ and I laugh. ‘My head is full of stupid foreign words that I have literally no use for.’

He goes, ‘You’re enjoying this, aren’t you?’

‘You’re spot-on I’m enjoying it. I haven’t seen my daughter for months and that’s down to you. So if you’re asking me to feel sorry for you, you’re borking up the wrong tree.’

‘I accept I should have told you when I found out.’

‘Yes, you focking should have – but you didn’t. When are you moving out, by the way?’

‘My parents said I could have their spare room until –’

‘I didn’t ask where you were going? I couldn’t give a fock if you end up living on Killiney Beach.’

‘Hey, I said I’d be gone by the time Honor comes home from Australia and I will, okay?’

‘What, so you’re going to drag it out until the very last minute?’

‘I’m going to spend every second I can with my son, yes. And I’m sorry if that inconveniences you, Ross.’

‘Well, Honor’s back at the end of next week. Just make sure you’re out of here before I go to the airport to collect her. Otherwise, I’ll tell her that you accused her in the wrong.’

And that’s when Hillary’s face suddenly lights up. He points at me and – I swear to God – goes, ‘Dada!’ and I end up having to laugh.

I’m there, ‘It sounds like you’ve got a lot of explaining to do to the kid, Fionn. I’m just going to go out and check when these two other fockwits are going.’

Out into the gorden I go. The boys are kicking a ball around. A soccer ball, I probably don’t need to add? There’s a rugby one lying on the ground next to the fence – an actual Gilbert – but it might as well be a focking Sudoku book for all the interest they have in it.

Sorcha’s old dear is looking up into the branches of a tree. I don’t know what kind it is – I find trees boring and a bit pointless, to be totally honest.

I’m there, ‘Are you two still here?’

She goes, ‘I’m just thinking that’s very unusual, isn’t it? That ash has already shed its leaves,’ obviously trying to change the subject.

I’m like, ‘So focking what?’

‘I’m just saying it’s very unusual,’ she goes, ‘for August, I mean.’

I’m there, ‘Yeah, thanks for that, Diarmuid Gavin. Should you not be out flat-hunting or something?’

‘We’ve found a place, if you must know.’

‘Where is it? Please say the Beacon South Quarter,’ because I know they absolutely hated living there. ‘That would make my literally day.’

‘It’s in Smithfield – very close to Edmund’s new office.’

‘It’s probably a focking dump, is it – hopefully?’

‘It’s very small –’

‘Good.’

‘There’s only one bedroom, but it’s perfectly sufficient for our needs. You’ll be pleased to know that we’ll be moving out tomorrow.’

I’m there, ‘At long focking last!’ and then I tip over to the Shomera to find her husband and have a gloat.

He’s actually in there with Sorcha. She’s going, ‘Dad, I’m not going to change my mind, okay?’

I’m like, ‘Dude, you’re wasting your breath. You’re out of here. Get focking packing.’

Sorcha’s there, ‘We’re not talking about the move, Ross. Dad is still trying to persuade me to run in this election.’

The dude flicks his head at me. ‘His father,’ he goes, ‘was on Morning Ireland this morning saying all sorts of hateful things about women drivers, about members of the Travelling community, about people from Cork. And the response he got from the public was overwhelmingly supportive. Who is going to counterbalance these arguments, Sorcha, if not you?’

‘There are plenty of good people out there – for instance, Muirgheal Massey.’

Yeah, I wouldn’t hold your focking breath, I think.

He goes, ‘But, Sorcha, this is your moment! Don’t you see that? Just as Mary Robinson was born to lead the Campaign for Homosexual Law Reform, so you were born to lead the fight against this new breed of hateful populism that’s sprung up everywhere.’

She goes, ‘There are other ways of fighting it, Dad, without standing for the actual Dáil.’

‘How exactly?’

‘The best way to fight Fascism is to raise children to know better.’

That’s pretty weak, in all fairness. I don’t know how I manage to keep a straight face.

He goes, ‘Sorcha, you are giving up the chance to make a difference – a real difference – to the Ireland in which your children will grow up.’

‘I’m sorry, Dad, but I already have a very important job. And that’s being a good role model to my children.’

Outside, through the open door of the Shomera, I hear Brian go, ‘Shut your focking whore mouth!’

And that’s when Sorcha suddenly stands up. She looks at me and goes, ‘I’m really sorry, Ross. I should have done this a long, long time ago.’

She walks over to the door and she goes, ‘Brian, please don’t use bad language like that!’

And Brian looks at her – I swear to God – like he thinks she’s lost her mind. He’s like, ‘What are you shitting on about?’

‘Brian,’ she goes, ‘we don’t use bad words like that in this house, okay?’

Brian looks at me then. He goes, ‘Stupid focking bitch.’

I just burst out laughing. I know I shouldn’t but there you go.

And that’s when Sorcha all of a sudden loses her shit. And I mean loses her shit in a major, major way. She roars at Brian. Her face is, like, proper Munster red. She goes, ‘Don’t you ever speak about me like that again!’ and Brian – I swear to God – kacks himself. ‘I am your mother and you will show me some respect! That goes for the rest of you as well! If I ever, ever hear a word like that out of your mouths again, I will scrub them out with soap and water! Do you understand me?’

She doesn’t wait around for an answer. She doesn’t need one. From the looks on the faces of the boys, it’s pretty obvious that she’s coming through loud and clear. Brian and Leo actually burst into tears. But I also know at that moment that the swearing has stopped for probably good.

It’s, like, twenty minutes later when Honor rings. Tempted as I am to tell her that we know that she was innocent all along, I keep my promise to her old dear to say fock-all.

Instead, I dance around the subject of her having got her first you-know-what, trying to sound sympathetic but not so sympathetic that she decides to confide in me.

It’s a minefield for any father.

I go, ‘I was really sorry to hear about, you know – blah, blah, blah. Just to let you know, we’re all thinking about you and hoping that you’re on the mend.’

She’s there, ‘Are you talking about me getting my first period?’

I’m like, ‘Jesus Christ, Honor, can we maybe talk about it without going into actual specifics?’

‘It’s not an illness, Dad.’

‘It’s kind of an illness. Jesus, if you saw your mother doubled over with the hot-water bottle clutched to her stomach, horsing into the Ben & Jerry’s and losing her shit with me for literally nothing, you’d say it was a definite illness. Although they don’t seem to be any closer to finding out what causes it. You’d have to wonder how hord they’re trying. Sorry, I’m babbling here.’

‘Would you prefer not to talk about it?’

‘I would, Honor, if it’s all the same to you. My face is really hot all of a sudden.’

‘You were the one who brought it up.’

‘And I regretted it straight away. I just wanted to check were you okay now?’

‘Yes, I’m fine. Anyway, I was just ringing to tell you that your stupid focking bitch of a wife has totally ruined my chances of staying in Australia.’

‘Has she?’

‘Er, she rang Erika and said she wanted me home because I’m going to be storting secondary school in a few weeks.’

‘You’ll be going to actual Mount Anville. That’ll be some day, Honor. Sorcha driving you there for the first time. There’ll be tears. I’m just warning you in advance.’

‘I told Erika to tell her to go fock herself.’

‘Right.’

‘I have no intention of going home. But now Erika is saying that I don’t have any choice in the matter – that I have to do what my mother says and that’s final.’

‘Am I detecting one or two cracks in your relationship? I’m sure your subscribers will pick up on it – yeah, no – if it storts to affect your on-screen chemistry.’

All of a sudden, I hear this, like, sobbing on the other end of the phone.

I’m like, ‘Honor? Honor, what’s wrong?’

She goes, ‘Dad, I don’t want to go home.’

I’m there, ‘Why not, Honor? Don’t you miss us?’

‘I miss you and I miss the boys.’

‘Well, then. Aren’t you looking forward to seeing us again?’

She goes, ‘I don’t want to go back to living in that house where they all hate me.’

‘They don’t all hate you, Honor.’

‘They do,’ she goes – and then she ends up really losing it. She’s suddenly crying so hord that her voice goes all high-pitched. ‘They think I poisoned … a baby, Dad … They think … I poisoned … a baby.’

And I’m there, ‘They don’t, Honor,’ and the words are out before I can stop myself from saying them. I’m just trying to comfort the girl – as her father. ‘They found out it wasn’t you after all.’

There’s just, like, silence on the other end of the phone. It seems to go on forever.

I’m there, ‘Anyway, Honor, it’s been lovely talking to you.’

But she won’t be so easily fobbed off. She goes, ‘What do you mean they found out it wasn’t me?’

I take a deep a breath. I know I’m going to possibly regret opening my mouth.

I’m there, ‘Yeah, no, Fionn found out that it was actually the boys dipping Hillary’s soother into the jacks, then sticking it into his mouth. That’s what was actually making him sick. So you’re off the hook. Anyway, I’m going to let you go.’

‘When did they find this out?’

‘Er, you’re kind of breaking up there, Honor.’

‘We’re both talking on landlines, Dad. When did they find this out?’

‘Okay, don’t go ballistic, but it was a few months ago.’

‘Months ago?’

‘Yeah, no, it was just after you left for Australia apparently. Although they didn’t tell me about it until last week.’

‘So why didn’t she ring me to apologize?’

‘Good question. Very good question.’

‘Well, what’s the focking answer?’

‘I don’t know. You’ve been pretty hord to get a hold of. You’ve been up to your eyes with the YouTube channel, then the whole Wellness Summit and Fashion Factory things.’

She goes, ‘Dad, stop lying for her!’ and she roars it at me. ‘She accused me of trying to kill my brother. They all did. Why didn’t she ring me to say sorry?’

I’m there, ‘I presume it was because she felt bad about sending you away.’

Oh, shit.

She goes, ‘Sending me away? What the fock are you talking about?’

I’m there, ‘Look, I’ve said way too much already.’

‘Tell me!’

‘Okay, basically, they decided between them – we’re talking Sorcha, Fionn and her dickhead old pair – that they were packing you off to Australia. But then you decided that you actually wanted to go?’

‘So they let me think that going away was my idea?’

‘You wanted to go and they wanted you gone. Everyone was a winner.’

She’s suddenly not crying any more.

She just goes, ‘Thank you for focking telling me,’ and then the line goes suddenly dead.

So it’s, like, a few days later and I’m walking up Grafton Street and I pop into Brown Thomas for one of my famous shit-and-runs.

‘Toilets are for the use of customers only,’ the dude in the top hat goes, staring at me stony-faced, then he holds the door open for me and laughs. It’s been a running joke between us for as long as I’ve been coming here to snip one off.

Up three flights of escalators I go. I’m thinking about my conversation the other day with Honor. She’s not replying to any of my WhatsApp messages. I’m just hoping she’ll have calmed down by the time she comes home next week. It’ll be a nice surprise for her when she finds out that Fionn and those other two fockwits are moving out.

The gaff that Sorcha’s old pair are moving into is tiny. There isn’t room to turn over in your sleep apparently. And I’m focking delighted, of course.

I reach the top of the final escalator and that’s when I see the massive queue of people, snaking from one end of the homewares floor to the other, then back again, then doubled over on itself a third time. There must be, like, six or seven hundred people here. I haven’t seen a queue like this in Brown Thomas since the height of the Celtic Tiger, when Michael Bublé was helicoptered in to launch his own range of paleo, refined sugar-free macarons in association with Ladurée.

And that’s when I spot JP and Christian smiling at me across the floor of the homewares deportment.

I’m like, ‘No focking way!’ quickly walking towards them. ‘No! Focking! Way!’

JP just nods and goes, ‘Yes focking way, Ross! Yes focking way!’

A high-five turns into a chest-bump turns into a hug. Christian gets the same.

‘You did it!’ I go. ‘You actually did it!’

Technically, he did it when he flogged the patent for ten mills plus a percentage from each bed sold. But seeing people queuing up in BTs to buy his Vampire Bed is the real confirmation that he’s arrived.

‘Your old man is up there and he’s smiling down on you, Dude. And I’ll tell you something else. I’d be shocked if Father Fehily isn’t standing next to him, saying, “The boy did good!”’

I look at Christian then. I’m there, ‘You as well. You back your friends and look what happens. Did he give you your two mills, by the way?’

Christian laughs. ‘Yes, Ross,’ he goes, ‘he gave me my two mills.’

‘Well, I hope Lauren apologized to you for doubting you. That girl would want to get off your case and stort appreciating what she has. Seriously, this thing couldn’t have happened to two nicer goys even if it happened to George Clooney and Ryan Gosling.’

JP goes, ‘Will we tell him our other news?’

I’m like, ‘Other news?’

‘The Russian firm that bought the bed have asked me to head up the operation for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. And guess who I’ve just hired as my Head of Morkeshing?’

‘Christian?’

‘You got it.’

‘Whoa, whoa, whoa – what does this mean for Hook, Lyon and Sinker?’

‘I’m selling it, Ross.’

‘Seriously?’

‘It’s time to move on. I’m just so buzzed about the future. Look at the queues, Ross. There’s a piece in the Irish Times this morning that says the Vampire Bed will allow developers to build aportments up to fifty percent smaller in size. Which means they’ll be able to provide up to twice as many homes every year.’

‘And all because people came around to the idea of sleeping standing up.’

‘This is what the Government meant when they said they trusted the morket to fix the problem of homelessness.’

‘I’m going to buy one.’

‘What?’

‘I came in to take a shit, but that can focking wait now. I’m joining this queue and I’m buying a bed.’

Christian laughs. He’s there, ‘Do you think Sorcha will be cool with sleeping vertically?’

And I’m like, ‘It’s not for us. It’s for Sorcha’s old pair. Yeah, no, they’re moving into a gaff in Smithfield that’s so small, apparently you can’t fart and brush your teeth at the same time.’

I say goodbye – and fair focks – to the goys again, then I join the queue. While I’m standing there, I end up ringing Sorcha.

I’m like, ‘Hey, Babes, I’ve decided to buy your old pair a little moving-out present – just to show there’s no hord feelings.’

She goes, ‘That’s, em, really decent of you, Ross.’

‘Hey, it’ll be worth it just to see the look on their faces.’

‘Oh my God, did you hear the RTÉ News this morning?’

‘Er, you do know who you’re talking to, Sorcha, don’t you?’

‘Your dad is, like, five points ahead in the latest opinion poll, with, like, a week to go until the election. I’m still waiting to see what Muirgheal and Croía’s big plan is going to be.’

‘Yeah, I wouldn’t invest too much hope in that. You’re not storting to suddenly regret it, are you? As in, not standing?’

‘A little bit. I would love to be a member of Dáil Éireann, pointing out the factual inaccuracies in all the statements that your dad and members of his porty make in the House. But then I look at the boys – and that includes Hillary – and I think, oh my God, I already have a job? We don’t need expensive Montessori schools to teach our children how to behave, Ross. That’s our job as parents.’

Who would have thought that stopping your kids from swearing was as easy as just telling them to stop focking swearing?

I’m there, ‘There’s no right and wrong way to raise kids, Sorcha. A lot of it, I’ve learned, is just making it up as you go along.’

All of a sudden, I hear this woman’s voice behind me, go, ‘Can we skip ahead of you in the queue? These ladies are pregnant … Thank you so much!’ and then, a few seconds later, the same thing again. ‘Can we skip ahead of you in the queue? These ladies are pregnant … Thank you so much!’

There’s no mistaking that focking voice.

I’m there, ‘Sorcha, I’ll see you at home,’ and then I hang up on her.

‘Can we skip ahead of you in the –’

I turn around and I’m like, ‘No, you focking can’t.’

She gets a fright when she sees me. It’s not half as big as the fright that I end up getting? She’s standing, like, six inches away from me – invading your personal space is a tactic she uses when she wants something – and I can see her face close up, the cracks and wrinkles showing through her foundation, her chin covered in patches of grey hair like blackberries on the turn.

‘Ross?’ she goes. ‘What are you doing here?’

I’m there, ‘Er, I’m buying a bed – what do you think I’m doing?’ and then I look at her six surrogates. Szidonia. Roxana. Loredana. Brigita. Lidia. And then another Lidia. Again, they’re in identical smock dresses – this time black – and they’re all beginning to show. I’m like, ‘Hang on a second, you’re not putting them in Vampire Beds, are you?’

She goes, ‘We haven’t the space for them all any more. We have the decorators coming to turn all of the spare rooms into nurseries for the children. So the girls are going to have to share a bedroom for the duration.’

‘You are seriously twisted. And I don’t mean twisted as in drunk. Even though you’re that as well. I can focking smell it off you.’

‘You’ve probably heard that your father’s streaking ahead in the opinion polls. Are you coming to the rally on Sunday?’

‘I told you. I don’t want anything to do with you – or him.’

‘I was rather hoping that you and I could put all of our history behind us. These babies are going to be your brothers and sisters, Ross, whether you like it or not.’

‘I don’t want anything to do with them either.’

She bitch-smiles and goes, ‘I’m sure you won’t always feel that way, Ross,’ and then she takes a step forward, taps the woman in front of me on the shoulder and – standing uncomfortably close to her – goes, ‘Can we skip ahead of you in the queue? These ladies are pregnant … Thank you so much!’

The grunt at the security gate won’t let me through. This six-foot-five Russian dude goes, ‘If your name is not on list, then you cannot come in,’ and I get a sudden flashback to being turned away from Club 92 back in the day and the long, drunken walk down the Leopardstown Road in search of a taxi.

I’m there, ‘You’re not listening to me. Chorles O’Carroll-Kelly is my actual father. Do you think I’d admit that if it wasn’t focking true?’

Suddenly, I spot Kennet through the wire-mesh fence. I call his name. I’m like, ‘Kennet!’ except he just ignores me, even when I shout it three or four times. He actually goes to walk away. So I shout, ‘The R … R … R … R … Rowuz of F … F … F … F … Finglas!’ and that gets his attention.

He comes walking over, all smiles. He’s wearing his driver’s uniform and he’s got a laminate pass hanging around his neck. He goes, ‘Ah, howiya, R … R … R … R … R … R … Rosser. I ditn’t see you theer.’

I’m there, ‘You tried to ignore me, you mean – until I reminded you that I knew your sordid little secret. Talk to this dude and tell him who I am.’

Kennet nods at the Russian dude to tell him it’s okay and the dude opens the gate and lets me into the backstage area.

The Phoenix Pork is absolutely rammers, by the way. Someone says that as many as one hundred thousand people might have come to hear what my old man has to say on the last Sunday before the actual election.

I go, ‘I need to talk to him.’

And Kennet’s there, ‘He d … d … d … d … dudn’t wanth to see addy wooden, Rosser. He’s throying to s … s … s … sabe he’s voice for he’s sp … sp … sp … spee-itch.’

I go, ‘How about I tell Dordeen that I saw you and her sister going at it like porn stors in my old man’s cor?’

He’s like, ‘’M …’M …’M …’Mon this way, so,’ and he leads me through the throng of porty workers and hangers-on to the old man’s trailer. I bang the door with my fist and the door opens. It’s Hennessy. ‘He’s not seeing anyone,’ he tries to go. ‘He’s saving his voice.’

But I just push past him. Saving his voice? That’s a joke. He’s smoking a cigor the size of Keith Earls and, at the top of his voice, he’s telling Fyodor about the time he shook the hand of Greg Norman – ‘the Great White Shork himself!’ – at Mount Juliet in 1995, just before Greg told him to get the fock off the fairway.

He spots me and goes, ‘Kicker! Just reminiscing about the good old days – quote-unquote! So you’ve come to hear your old dad make the speech that’s going to decide the election, have you?’

I’m there, ‘No, I’ve come to talk to you about the old dear.’

It’s the fact that I call her the ‘old dear’ – and not, for example, ‘that ugly, refuse sack of Botox, bitterness and animal organs that you for some reason married’ – that convinces him that this is serious.

He goes, ‘Okay, clear the room, people, while I speak to the famous Ross for a moment!’

When everyone has gone, I turn around to him and go, ‘You’ve got to stop her before it’s too late!’

He’s like, ‘Too late? What on Earth are you talking about, Kicker?’

‘You can’t let her bring six babies into the world. She’s only doing it to get back at me for letting her choke on that olive.’

‘I’m afraid the proverbial die has been cast, Kicker! Each of the girls is with child as it were! There’s no turning back now!’

‘You could let them go.’

‘Let them go? Good Lord!’

‘I mean, you could buy them each a plane ticket and send them back to –’

‘Chis¸ina˘u!’

‘You said it, not me.’

‘But they’re carrying your brothers and/or sisters, Kicker!’

‘Just because we have the same mother and father doesn’t make us brothers and sisters.’

There’s a knock on the door. Hennessy sticks his head around it and goes, ‘Charlie, it’s time!’

The old man stands up. He goes, ‘I’m sorry to cut our little tête-à-tête short, Ross! I have a General Election to win!’

He walks out of the trailer and through the VIP area towards the makeshift stage. I spot the old dear, surrounded by her surrogates. The old man hugs and kisses her and she whispers something in his ear. Then – un-focking-believable – he kisses the bellies of each of the surrogates, presumably for luck, then he walks up the steps to the stage.

I hear his name announced by, I don’t know, whoever. It’s just like, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I’m proud to introduce to you … to the next Taoiseach … Charles … O’Carroll … Kelly!’

There’s, like, a roar from the crowd – and – yeah, no – it is deafening – as the old man steps out onto the stage.

He’s there, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I will be brief – although not quite as brief as Leo Varadkar’s time in office!’

There’s, like, howls of laughter from the crowd, then a round of applause that goes on for a good thirty seconds.

‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ he goes, ‘in the coming week, the voters of this country will have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to do something that is truly revolutionary! We have a chance to boot out the career politicians who have helped turn this country into a vassal state! We have a chance to remove from office those politicians who stood around like eunuchs in a proverbial harem while unelected bureaucrats with cross faces told you, the people of Ireland, that you would have to cover billions and billions of euros’ worth of debt that had nothing whatsoever to do with you! Because your children, and your children’s children, and twenty generations of children yet unborn, will be paying for the greed of rich men and the incompetence of politicians who were elected to represent you but don’t represent you at all!’

People stort booing.

‘You’re angry!’ the old man goes. ‘And you’re bloody well right to be angry! You’ve lived through a decade of – inverted commas – austerity! And what was it all for! It was the price they decided you should pay to remain part of a club that doesn’t care a bloody well jot about you – that would sell this country out at the first opportunity! And meanwhile, across the water, we see our wonderful friends, the good people of Great Britain, doing what we should have done ten years ago – standing up to the tyranny of Brussels in the same way they stood up to the tyranny of a certain Adolf Hitler! And this time, I say, let us be on the right side of history! This time, let us stand with them!’

There’s, like, a huge roar of approval from the crowd. And that’s when I see it in the distance, rising slowly from the ground – a blimp that looks, it has to be said, exactly like my old man.

He must see it as well, but he tries not to let it put him off his speech.

He goes, ‘Unfortunately, we, in this country, do not have leaders of courage! We do not have leaders of substance! We have Varadkar! And Coveney! And Murphy! And Harris! The smartest boys in the Sixth Year Common Room! We have a Taoiseach who admires people who get up early in the morning, remember, to ensure we all keep chipping away at that debt burden like good little Europeans!’

The blimp storts to rise and suddenly it’s blocking out the sun and casting a humungous shadow over the crowd. People are turning around and booing. There’s, like, definite anger in the air.

The old man goes, ‘And this is what happens, ladies and gentleman, when you challenge the authority of our smug, privately educated, ruling elite! Instead of answering your arguments, they try to ridicule you for having the courage to think differently from them!’

Behind me, I hear Fyodor go, ‘Where is my gun?’

‘We must not let them win!’ the old man goes. ‘We! Must! Not! Let! Them! Win!’

Kennet sidles up to me then and he says the most random thing. He goes, ‘Sh … Sh … Sh … Sh … Shadden and Ronan seem to be habbon the t … t … t … t … t … toyum of their loyuvs, Rosser!’

I turn around to him and I go, ‘What are you shitting about?’

‘Thee weddent away, thee did. D … D … D … D … Did Ronan not ted you?’

‘No, he didn’t ted me. Where the fock have they gone?’

‘Thee weddent to V … V … V … V … V … Vegas. With Rihatta-Barrogan – a p … p … p … p … proper famidy hodiday, wha? And alls Ine saying is thee l … l … l … l … looked veddy lubbed up in the ph … ph … ph … phoros that Shadden purrup on the F … F … F … F … Facebuke. Dordeen says to me sh … sh … sh … she wootunt be surproyzed if thee kem back m … m … m … m … maddied!’

That’s when I hear a loud bang like a gunshot. I look over my right shoulder and I see Fyodor lowering a rifle. There’s, like, screams in the crowd.

The old man goes, ‘Don’t be alarmed, people, this man is here for our protection!’

It turns out the dude missed the blimp but ended up hitting the rope that was, like, tethering it to the ground. Because suddenly the thing lifts off and storts blowing across the pork, sending screaming people scattering for cover. The entire crowd turns and watches in absolute horror as this ginormous, Chorles O’Carroll-Kelly-shaped balloon sweeps over the tops of the trees and towards Áras an actual Uachtaráin.

The old man’s there, ‘This is what they do, my friends, to people who disagree with their agenda! They try to sabotage them! They try to silence them! Good God, I can only hope, for his sake, that poor President Higgins isn’t home and looking out the window! Imagine the fright the poor chap will get if he sees that thing coming towards him! Doesn’t bear thinking about!’

‘They’re m … m … m … m … med for each utter,’ Kennet goes.

I’m like, ‘What?’

‘Shadden and Ronan. They’re a l … l … l … l … l … lubbly cupiddle. Bout t … t … t … toyum he made an hodest wooban ourrof her. And joost think ob it, Rosser – me and you and Ch … Ch … Ch … Ch … Ch … Cheerdles there will be famidy!’

There’s an enormous crash then, like the sound of a building collapsing. The Charles O’Carroll-Kelly blimp has crashed into the front of the Áras, sending bricks and slates raining down on the lawn below.

The old man goes, ‘They must not – they will not – be allowed to silence our movement!’

And then the crowd bursts into a chant of, ‘CO’CK for Taoiseach! CO’CK for Taoiseach! CO’CK for Taoiseach! CO’CK for Taoiseach!’

Sorcha asks me if I’ve voted yet, even though I’ve actually never voted – as in, like, ever? Seriously, after twenty years together, sometimes it’s like we’ve never even been introduced.

‘Yeah, no,’ I go, ‘I’m, er, hoping to get out to do it at some stage.’

This is us in the kitchen, by the way. The boys are playing quietly with their Lego on the floor. They’re very focking wary of their mother all of a sudden.

She’s there, ‘Because this is an important election, Ross. Possibly the most important? As my dad was just saying, this is the one that will decide whether we remain port of Europe or disappear down the same – oh my God – rabbit hole as Britain and the States.’

I’m like, ‘I noticed this morning that we were out of Heineken. Yeah, no, I might vote on the way back from the off-licence.’

I don’t even know where I’m supposed to do it? And aren’t you supposed to be, like, registered or some shit?

I’m there, ‘Are you looking forward to seeing Honor?’

She’s arriving home tomorrow, by the way.

She goes, ‘I am, Ross. I know you might not believe me, but I actually am?’

I’m there, ‘And you definitely think that not telling her the truth about what happened to Hillary is the right way to go?’

‘She would never, ever forgive me, Ross.’

‘Yeah, you’re, er, probably right there.’

‘This way we at least have a chance to stort over again. I think the break from each other might turn out to be the best thing that ever happened to us. It gives us a chance to reboot our relationship – to be the best friends that I’ve always dreamt we would be?’

Yeah, good luck with that, I think.

I knock back the last of my coffee while she checks the news on her phone.

‘Oh my God,’ she goes, ‘Muirgheal, Croía and her niece have been arrested and chorged with causing a million euros’ worth of damage to the roof of the Áras.’

I’m there, ‘I’m not surprised. Three dopes.’

‘And endangering the lives of the public. That’s, like, oh my God! It says here that when chorged, Croía refused to accept the validity of the chorge until it was put to her by a Bean Gorda. When a Bean Gorda put the chorge to her, she accused her of being a hapless stooge for a patriarchal organization that oppresses women and the right to free speech and freedom of expression.’

‘Hilarious.’

‘I’d say that’s Muirgheal’s seat probably gone as well.’

‘Well,’ I go, standing up, ‘I can’t say I feel sorry for either of them. Is Fionn finished packing up all his shit, by the way?’

She’s there, ‘Ross, please don’t gloat. He’s upset enough as it is.’

‘I’m going to go out and grab that Heineken. It’s a day of celebration.’

‘Don’t forget to vote on the way back.’

‘Yeah, no, I’ll go with the flow, Babes, and see what happens.’

All of Fionn’s shit is piled up in boxes in the hallway, waiting for him to put it into his cor. He’s standing there and he’s saying his final farewells to Hillary. He’s looking into the little lad’s eyes and you can tell he’s trying his best not to cry. He’s going, ‘I won’t be here any more, Hillary, but I won’t be very far away either. And I’ll come and visit you all the time.’

And I’m like, ‘Yeah, make sure and ring ahead first, Fionn,’ as I walk past them, then as I’m going out the front door I stort singing Paul Brady’s ‘The Long Goodbye’.

I get into the cor. I feel actually good. I’m just about to stort the engine when my phone suddenly rings. I check my caller ID and I notice that it’s Joe Schmidt. I answer and there’s, like, five seconds of silence on the other end.

‘Joe,’ I shout, ‘you’ve orse-dialled me again!’

Then I hear his voice – God, it’s like honey – go, ‘Nah, Oy actually mint toy ring yoy thus toym, Ross! How are yoy goying?’

I’m like, ‘Er, yeah, no, cool.’

‘Oy just wanted toy sind yoy back your Rugboy Tictucs Book.’

‘Oh, right.’

‘Oy wanted toy git your addriss.’

‘It’s Honalee, Vico Road, Killiney, County Dublin.’

‘Got ut. Boy the woy, that mooyve on poyge eight – yoy knoy the one Oy moyn?’

I’m there, ‘The one I designed for Garry Ringrose and Jordan Larmour?’

‘That’s ut. That was prutty smaaht.’

‘Do you think?’

‘Oy moyn royloy, royloy smaaht. Ross, Oy hoype yoy doyn’t moynd but Oy talked toy one or toy poyple abaaht yoy.’

‘Haters gonna hate, Joe. Was one of them your mate Gatland?’

‘When are yoy gonna give yourself some cridit? Yoy’ve got all thoyse great oydeas abaaht the goym and yoy’re doying nothing wuth them. All because yoy’ve got some koynd of chup on your shoulder.’

‘Some of kind of –?’

‘Chup.’

‘I thought that’s what you said. You were talking to Gatland then.’

‘Look, Oy’m gonna sind yoy a tixt missage in a few munnets. It’s just the noyms and numbers of a few contacts of moyn – AIL, one of toy Linster schools – whoy could use a coych with frish oydeas.’

I swear to fock, I suddenly feel like nearly crying.

I’m there, ‘Why are you doing this?’ because I honestly can’t remember the last time anyone was this nice to me.

He goes, ‘Because Oy think your daughter’s royt – Oy think yoy’ve royloy got something. Nah, just ring thoyse numbers Oy’m sinding yoy. And lit thus boy the staaht of something, okoy?’

I tell him it will. We both hang up. And then about twenty seconds later, my phone beeps and it’s a text message. I look at the names. DLSP. Old Belvedere. Newpork Comprehensive. Gorey Community School. Pres Bray.

I actually have a little chuckle to myself thinking about what Father Fehily would say if he knew I was thinking of coaching Pres Bray. And then it suddenly hits me. I’m thinking about Father Fehily and all these memories from my schooldays come suddenly flooding back. I’m remembering one time, against St Mary’s, Fionn taking an unbelievably hord hit just so he could play a pass to me at exactly the right moment for me to score a try. I’m remembering him another time throwing himself into the middle of a group of Terenure players who objected to me flashing my sixpack at their supporters and taking a punch in the face for me. I’m remembering him another time trying to give me grinds the night before we sat Leaving Cert Maths Paper I and explaining everything to me without ever losing his patience, even though nothing actually went into my head in the end.

I stare at the door of the house and I think, ‘What the fock have you become, Rossmeister?’

I get out of the cor and I walk back to the house. I let myself in. Fionn looks at me. He’s got, like, tears streaming down his face as he says his last goodbyes to Hillary.

‘Pick up all your focking shit,’ I go, ‘and put it back upstairs.’

He’s like, ‘What?’

I’m there, ‘I’m going to end up tripping over it and breaking my focking neck. Then I’d be no use to any club. Put it back upstairs. In your room.’

Sorcha comes out of the kitchen. She goes, ‘Oh! My God!’

Fionn’s there, ‘Are you saying –?’

‘I’m saying you can stay,’ I go. ‘I’m saying you don’t have to move out – if you don’t want to.’

He’s in shock.

He goes, ‘What changed your mind?’

I’m there, ‘The short answer is rugby.’

‘Jesus, Ross.’

‘The long answer is that I’ve just spent the entire summer separated from my daughter and I’ve missed her more than I have the words to say. And I wouldn’t want to think of anyone else going through what I just went through – even you, Fionn.’

He goes, ‘That’s very decent of you – considering.’

We’re just, like, staring hord at each other.

Sorcha’s there, ‘What about my mom and dad, Ross?’

I don’t take my eyes off Fionn. I’m there, ‘I didn’t play rugby with your mom and dad, Sorcha.’

And she knows just to leave it at that.

I bend down and I pick up a box. It’s got, like, a mobile inside with what I’m presuming are all the planets in the – I think it’s the right word – but sonar system?

‘Come on,’ I go, ‘let’s get all this focking junk back up to your room.’

The same words keep getting used. Stunning. Shocking. Staggering. Chorles O’Carroll-Kelly’s New Republic are on course to win an overall majority as counting continues in twelve constituencies and it’s all anyone in the country seems to be talking about.

People are walking through the doors of Arrivals, having obviously read the news on their phones, and they’re hugging loved ones and going, ‘Is this for real?’ and ‘He’s a Fascist lunatic.’

You’d genuinely have to wonder who actually voted for him because no one seems to be admitting it.

I’m looking up at the little monitor.

‘Honor’s flight has landed,’ I go.

But Sorcha’s not listening to me. Like everyone else, she’s just glued to her phone. ‘They’re saying that Ireland leaving the European Union would require a change in the Constitution,’ she goes. ‘That’s what my dad said this morning. So there’s still a chance to stop it from happening.’

I’m there, ‘Did you hear what I said? Honor’s plane landed ten minutes ago.’

She puts away her phone. She goes, ‘I’m sorry. I’m just nervous about seeing her again.’

Yeah, not half as nervous as I am? I literally haven’t spoken to the girl since I let it slip that she was basically sent to Australia – and for a crime we now know she didn’t commit.

Leo goes, ‘Mommy, when is Honor coming?’ and Sorcha smiles sweetly, leans down and kisses him on the top of the head.

‘She’ll be coming through those doors any minute now,’ she goes.

The boys are holding the little signs they made that say ‘Welcome home, Honor!’ and they’re genuinely giddy with excitement.

Out of the corner of my eye, I catch Sorcha looking at me with a big smile on her face. Yeah, no, things are getting back to nearly normal between us. A year ago, I wouldn’t have believed we’d ever be this loved up again.

She stood next to me this morning when I made the phone call – a supportive hand on my shoulder. I said I’d heard rumours they were looking for a coach. They said they’d heard good things about me. I asked how good? They say really good. So I arranged to swing out there next week for a chat and a look at their set-up.

And when I say ‘out there’, I’m talking about – believe it or not – Bray. Of all places.

That’s right. I’ve got an interview on Monday morning for the position of senior rugby coach in Presentation College Bray. I know a lot of people – my critics, mostly – will get a great kick out of that. I’ve said a lot of bad things about Bray over the years. And, while I stand over every focking word of it, the old romantic in me loves the idea of taking this school from – let’s not dodge this – Wicklow and opening my Rugby Tactics Book to them.

Father Fehily, who spent a lot of his life doing missionary work in Botswana, used to say, ‘You go where the need is greatest,’ and I can’t think of anywhere more in need than Bray.

I’m also conscious of the fact that twenty-something years ago, Joe Schmidt storted his coaching career in Ireland by leading Wilson’s Hospital in Mullingor to victory in the Leinster Schools Senior Cup Section ‘A’ final, and there’s a little bit of me that likes the idea of following in the great man’s footsteps.

You never know, I might even give Phinneas a bell to ask him if he fancies being my assistant?

Yeah, no, things are finally coming together. Sorcha’s old pair are moving out tomorrow. And aport from my old man threatening to lead the country into ruin and my old dear giving me six brothers and/or sisters that I don’t want, it feels like things are returning to normal again. My only real worry now is …

‘Honor!’

Brian, Johnny and Leo all shout it at exactly the same time. I look and I see my daughter pushing her trolley, loaded with baggage, through the Arrivals gate. The boys can’t contain themselves. They run towards her, then they throw their orms around her waist and she laughs, then sort of, like, hunkers down to their level and gives them each a hug and tells them that she missed them.

She’s definitely changed. She looks, I don’t know, taller. Or maybe not taller. Just not a child any more.

Our eyes meet. I still don’t know whether she’s pissed off with me or not. Then suddenly she breaks into a run and she throws her orms around me and it’s like the last few months never happened. It’s like we were never even aport. She goes, ‘Hey, Dad!’ and she’s crying.

And I’m crying, too.

I’m like, ‘Hey, Honor! God, I missed you so much! Hey, I’m possibly going to be coaching Pres Bray in the Leinster Schools Senior Cup next year and it’s all down to you. And I don’t mean that in a bad way.’

And then the most random thing happens. She spots Sorcha standing behind me and she breaks away from me. Sorcha doesn’t move. She just goes, ‘Hi, Honor,’ and her voice sounds, I don’t know, cautious and uncertain. For ten seconds, I swear to fock, Honor doesn’t say shit. She just stares at her old dear, then she walks towards her and I’m still half expecting her to slap her across the face. She doesn’t, though. She does the same to Sorcha as she did to me – throws her orms around her waist and hugs her tightly.

Sorcha looks at me and mouths the words, ‘Oh! My! God!’ and she holds her daughter like I haven’t seen her hold her in years.

Honor goes, ‘I’m sorry, Mom! I’m so sorry!’

And that ends up setting Sorcha off. She goes, ‘No, Honor, I’m the one who’s sorry!’ and she’s suddenly bawling her eyes out.

I’m thinking, Oh, holy shit, she’s not going to tell her, is she? But she does end up telling her? Yeah, no, it all comes out – there in the middle of the Arrivals hall.

‘I accused you of trying to poison Hillary,’ she goes, ‘and I know that it wasn’t true. Even worse, Honor, I found out weeks ago that it wasn’t true and I never said anything.’

Er, try months ago?

But Honor’s there, ‘I don’t blame you for not believing me, Mom. I did so many bad things.’

‘That’s not all,’ Sorcha goes. ‘I let you think that going to Australia was your idea, but the truth was I wanted to send you away.’

Again, Honor takes this better than she did when I told her on the phone last week, having had time to, like, process it?

She goes, ‘Mom, I don’t blame you. I’m horrible.’

Sorcha’s like, ‘You’re not horrible, Honor. You’re my little girl. And I love you so much.’

Someone’s changed their tune. But now is not the time to pull her up on what she said a few weeks ago. Because mother and daughter are having a definite moment.

‘Spending time with Erika was the best thing that ever happened to me,’ Honor goes. ‘She taught me to appreciate all the good things I have in my life and that includes you, Mom.’

Sorcha’s like, ‘Oh, Honor!’

‘She just, like, talked to me all the time about how lucky I was to have a mother like you and I’m so sorry that I treated you so badly.’

‘Hey,’ Sorcha goes, ‘we can stort again, Honor. You’re going to be storting in actual Mount Anville in two weeks and it can be a whole new beginning for us. You’ll be doing all the things I did, Honor. The St Madeleine Sophie Barat Prayer Circle. The Model United Nations. We can be, like, best, best friends.’

Honor’s like, ‘I really want that, Mom. I really do.’

‘Come on,’ Sorcha goes, ‘let’s go home.’

‘I can’t wait to see Hillary.’

‘On my God, he’s gotten so big, Honor!’

The two of them stort walking in the direction of the cor pork and I think to myself, Fock my old pair. Whether it’s having kids or destroying the country, I don’t care what they do any more. Because these people here are my priority – one, two, three, four, five, six of us, plus Ronan, whatever the fock he decides to do.

And plus – I’m going to say it – Hillary. Okay, he’s not mine, but he’s theirs? He’s Sorcha’s son and a brother to Honor, Brian, Johnny and Leo. And that makes him family. End of.

I grab Honor’s trolley and I tell the boys that we’re going. And, as I stort pushing it, I notice that Sorcha and Honor are holding hands and I think to myself, Okay, what kind of miracle is that? And then something else pretty miraculous happens. I’m aware of Brian and Leo sort of, like, bickering with each other – not effing and blinding and threatening each other with extreme violence like before. Yeah, no, they’re just having a little orgument, the way normal brothers do. I turn back and I go, ‘What’s wrong, goys?’

And that’s when Leo says the most incredible thing to me. He goes, ‘Dad, who’s the best – Johnny Sexton or Owen Farrell?’

And you get days like that in your life, where all your problems seem to just fall away of their own accord and you can suddenly see the future, bright and happy, stretching out in front of you.

‘That’s a stupid focking question,’ I go. ‘But I can’t tell you how happy I am that you asked it.’