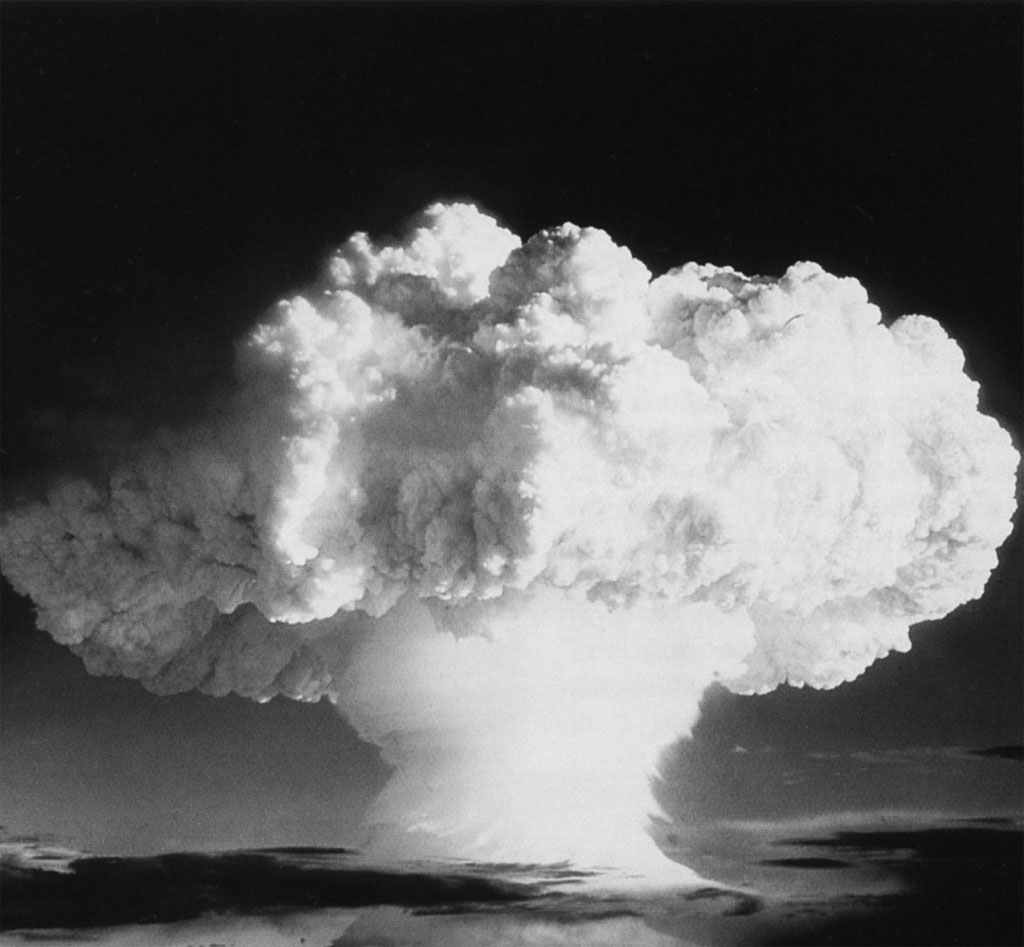

In 1952 the USA carried out the first test explosion of a hydrogen bomb on a remote Pacific atoll.

The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki appeared to usher in a new age in which whole cities could be destroyed in a moment, and humankind might come to destroy itself. As it turned out, although the United States enjoyed a monopoly of nuclear weapons from 1945 until 1949, it didn’t use them again.

During the Second World War, fearing that the Nazis might be developing such weapons, the USA embarked on its own programme. The resulting Manhattan Project deployed an international team of experts, and led to the production of the A-bombs used against Japan.

In the early years of the Cold War (see here ), the nuclear strength of the USA allowed it to demobilize rapidly after 1945, and to act freely around the world. This period of confidence ended in 1949 when it became clear that the Soviet Union had also been able to develop its own atomic weapons, an achievement that reflected not only Soviet advances in science and technology, but also the effectiveness of its espionage networks in the West.

The Soviet success disconcerted the Americans, and encouraged them to develop a much more powerful nuclear weapon, the hydrogen bomb. They tested the first device in 1952, on Eniwetok atoll in the Pacific, and pictures of the fireball, 5 kilometres wide and rising 17 kilometres high, astonished and terrified the world. The following year the Soviets tested their own H-bomb.

Other powers, first Britain then France and China, developed their own A-bombs, and then H-bombs. However, the key powers were still the United States and the Soviet Union, who built up massive arsenals. At first, nuclear weapons took the form of bombs designed to be dropped from aircraft, but by the late 1950s both sides had developed long-range missiles to deliver nuclear devices, either ground-launched or fired from submarines. These missiles moved much faster than aircraft and would be far harder to track or intercept.

The two powers amassed formidable arrays of long-range weapons. This escalation was inspired by the idea that only a massive arsenal could deter the other side from attack. The theory of mutually assured destruction (‘M.A.D.’) suggested that where two sides both had overwhelming nuclear arsenals, a first strike by one would obliterate both. Planners identified targets that would have resulted in the deaths of hundreds of millions. Civilians grew used to emergency drills and procedures that would have defended them from neither blast nor radiation. Children were even taught to take shelter under their desks at school.

Whether or not these nuclear arsenals prevented full-scale war is an open question. In 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower of the United States warned his Soviet counterpart of the risk that such a war might wipe out human life in the northern hemisphere. Eisenhower abandoned the policy of the ‘rollback’ of Soviet power in Eastern Europe precisely because he feared nuclear devastation. Instead, the superpowers fought smaller-scale but hugely costly indirect wars with each other’s allies, as in Korea and Vietnam, but withheld the full range of their forces. Eisenhower did, however, threaten the use of nuclear weapons in order to bring the Korean War (1950–3) to an end after Chinese troops had intervened. Their use also briefly looked imminent during the US–Soviet stand-off in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, after the Soviets deployed missiles on Cuba, close to the continental USA. In the end, the Soviets withdrew their missiles.

‘I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.’

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist in charge of developing the first atom bombs, on witnessing the first test explosion in the desert of New Mexico in 1945. He was quoting from the ancient Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita .

In the 1970s, interest in nuclear-limitation agreements developed as part of détente (the cautious improvement of relations between the USA and the Soviet Union). After early agreements, relations cooled between the two superpowers, but they moved on to new and more comprehensive agreements from the late 1980s, and these helped to bring about the end of the Cold War (see here ).

Instead, the focus shifted to fears about nuclear proliferation – the danger that other states, including aggressive ‘rogue’ states, or even terrorist groups, could gain a nuclear capability. In addition to the USA and Russia (as it is now), the list of nations with nuclear-weapons capabilities now includes China, France, Britain, India, Pakistan, North Korea and, allegedly, Israel. The future of proliferation is unforeseeable, and there is also the worrying prospect of the use of bacteriological and chemical weapons, or of a low-tech ‘dirty bomb’ combining conventional explosives and radioactive material.

The nuclear age also saw the development of nuclear energy as a peaceful tool, used to generate power and seen at first as a modern, less polluting alternative to coal. However, a series of accidents, particularly an explosion in 1986 in the reactor at Chernobyl in Ukraine (then part of the USSR), led to concerns about potential dangers from leakages of radiation. Such fears were revived by the earthquake that damaged the Fukushima nuclear power station in Japan in 2011. The dilemma remains that nuclear energy offers a relatively benign environmental prospect if it can be made safe. Quite how problematic that ‘if’ is continues to be the subject of controversy.