DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER

34th President, 1953–1961

Historian: William I. Hitchcock

William Hitchcock is a University of Virginia professor and historian specializing in twentieth-century American history, with a focus on the world wars and Cold War. He appeared on C-SPAN’s Q & A series on May 3, 2018, to discuss his book, The Age of Eisenhower: America and the World in the 1950s.

The period from the death of Franklin Roosevelt to the death of John Kennedy—1945 to 1963—is a period in which [Dwight] Eisenhower’s personality, his ideas, his values, and, of course, his presidency really dominated American public life. In that period, I think it’s safe to say he was the most well-known, well-liked, popular American because, of course, of his record in the war years. But, even as he was emerging as a presidential candidate and then as president, he was overwhelmingly America’s favorite public figure. His instincts, his values, his presence really became part of American life in the 1940s and ’50s.

I call his the “disciplined presidency.” Eisenhower, in the way he carried himself and the man that he was, was a disciplined man, a great athlete when he was young, and an organized man in every respect, very methodical. That’s how he ran the White House, too. He was extremely organized. A lot of people, especially the young senator and future president John Kennedy, criticized Eisenhower’s stodginess for being so disciplined and organized and predictable. For Eisenhower, it meant that when crises came, he had a plan. He knew how to respond. He knew who to turn to. He used to say, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” So, you’re always thinking, “What’s over the hill? What crisis might erupt? We should be thinking about it.” He was very systematic in the way that he governed. He met the press every week; he met congressional leaders every week; he chaired the National Security Council every week; and he had his thumb on the government. He trusted the process. He believed the federal government could work well if it was well led. I think he still stands as a real model to learn from.

Harry Truman loved Eisenhower in 1945, and even up through 1948, he thought that Eisenhower would be a good president. He thought he might be a Democrat, that’s why. Nobody knew what party Eisenhower was in when he was in the army. Truman thought maybe he could get Ike to run, and Truman said, “I’ll be your vice president.” But in 1945, he really did say to Eisenhower while they were touring Berlin… for the Potsdam meeting, “General, I will do anything that I can possibly do to help your career, and that includes your being president.” He admired Eisenhower so much, and that was a time when Truman had just become president, so, I think he was still in awe of Eisenhower.

By 1952, you can tell there’s a frosty relationship, and that’s because Eisenhower had been speaking out politically in 1951 and ’52, criticizing the New Deal, criticizing Roosevelt, criticizing Truman himself, criticizing the big federal programs of the New Deal. He ran as a conservative in 1952, Eisenhower did. Truman [returned fire] saying, “Well, one day he’s a conservative, one day he’s a liberal. You can’t trust him.” That’s like a lot of people who run for president. They tend to say different things to different audiences. Eisenhower was just as good a politician as anyone. But the relationship between these two men soured, and it’s really too bad.

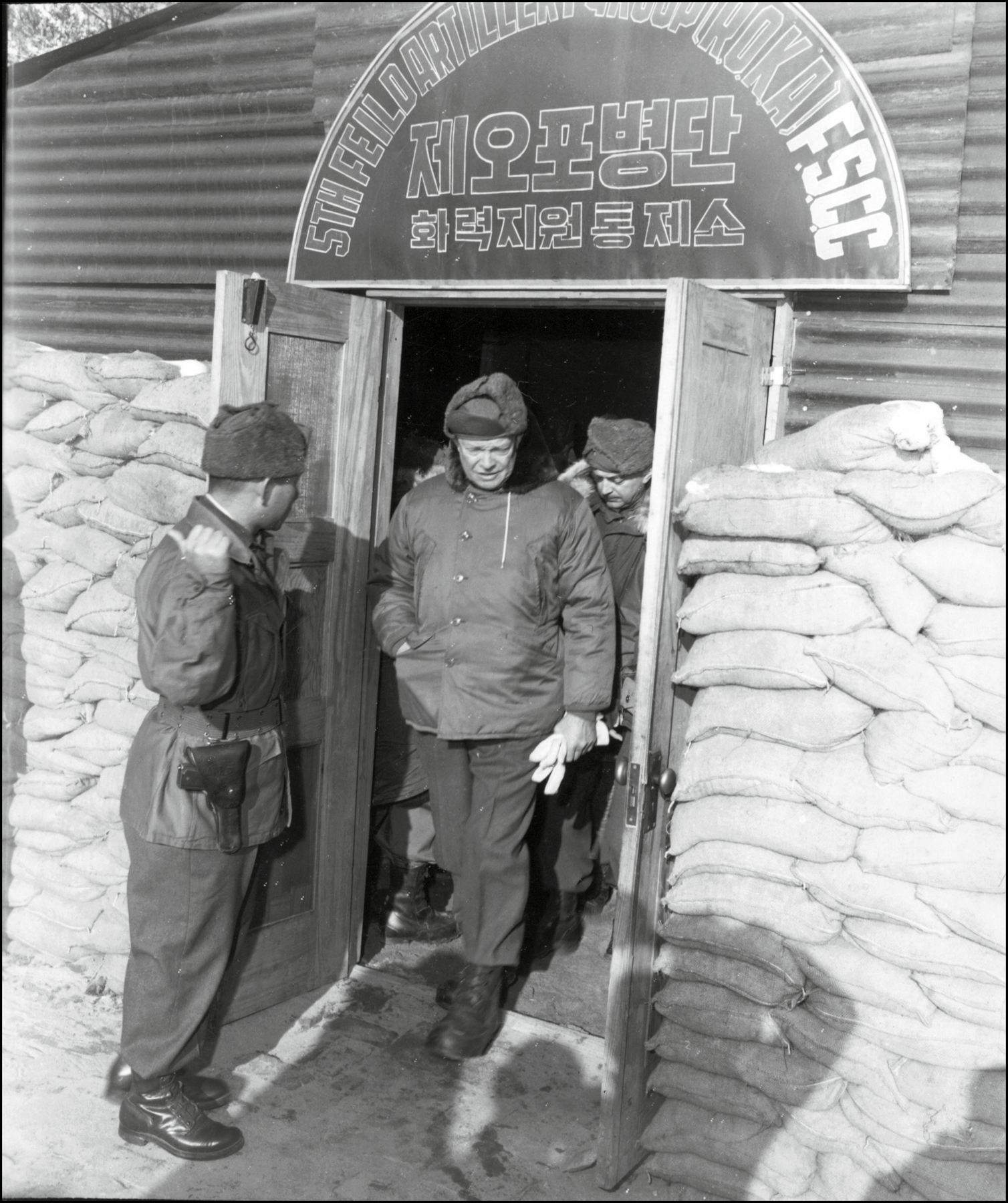

… Eisenhower did say that he would go to Korea during the [1952] campaign. He wanted that to have the effect that [he] knew that it would have. When the former Allied commander of World War II says, “I’m going to go to Korea and see what’s going on there for myself,” as a candidate, he knew it would be a provocation. It would suggest that Harry Truman wasn’t running the Korean War terribly well. He wanted to have that as a bombshell to drop in the campaign. He did drop it quite late in the campaign, in October, and he knew that President Truman would be offended. Truman was offended. He called it a “piece of demagoguery.” After the fact, many people debated whose idea it was. [His press secretary, James] Hagerty, said at one point that other members of the [campaign] team had suggested it, but in fact… it was Eisenhower’s idea. He said to Hagerty, “Just keep it quiet; we’ll use this when we need to.”… Americans responded by saying that the most successful soldier in American history is going to go to Korea to figure out why we’re not winning this thing and maybe put an end to it. Everybody knew at that moment he had won the election.

[He went there in] December 1952, so you can imagine how cold it was in Korea. He hadn’t become president yet. Civil and military relations are pretty tense at this moment. Truman had had to fire General MacArthur, the commander in Korea, in 1951 because MacArthur had said Truman was not handling the Korean War well. And here goes President-elect Eisenhower to Korea basically saying the same thing: that something’s wrong; we’d better fix it; I’m going to go find out what’s the matter. He did go, and it actually helped his choice of policy in Korea. He came back having seen the battlefield, having seen how difficult it was to fight in Korea, how stalemated it was, how mountainous it was. He came back determined, one way or the other, that he was going to end this war, but not necessarily through an armistice. For a while he thought he would increase the pace of operations in Korea until there was an opportunity to reach out for the armistice, which he was very happy to get, because he knew that this war wasn’t popular. It needed to be brought to an end.

Eisenhower believed he had a great deal to do with [ending the Korean War] because he believed that he had rattled the nuclear saber, saying, “If we don’t get this settlement, we might have to go nuclear in Korea.” He believed that this had frightened the Chinese into putting pressure on the North Koreans to agree to an armistice. But we now know a great deal about what was going on with the other side. We know that the death of Joseph Stalin in March of 1953 had a big impact on both China and North Korea. Stalin was all in favor of the war, and when he died in March of ’53, the new leadership in the Soviet Union said, “We would love to bring the Korean War to an end. It’s dangerous. It might get worse. It might lead to a nuclear exchange. We don’t want that.” They urged the Chinese and the North Koreans to agree to an armistice. It was the pressure from the communist side, the changes going on in the communist bloc, that led to the breakthrough. They came to Panmunjom and said, “Let’s have an armistice.” But I will say, Eisenhower accepted the armistice, which he could do because he was a general. He was a Republican who had great credentials as being a military man.

His [1953] inaugural address opened with a brief prayer.… He didn’t pull it out of the scripture. He said, “I’m just going to write something myself.” A deeply spiritual man, he was raised in a family of deeply spiritual parents who were members of the River Brethren Church, an offshoot of the Mennonites. His forebears had come from Pennsylvania. They’d been essentially what we think of as Amish. His father read a piece of scripture every night in the family living room, and all the boys had to sit around and listen. He knew his Bible backwards and forwards. He did not enjoy attending church, and when he went in the army, he steered clear of organized religion. This is so interesting, so surprising, so important for Eisenhower: when he became president, he said, “I have to be seen as a public man of faith. I have to go to church every week, so I need a regular church.” Mamie was a Presbyterian, so he went to the Reverend Edward Elson of the National Presbyterian Church here in Washington, DC, and he was baptized. A sitting president was baptized February 1953. He then used religion as a very important part of his public personality as president.

Eisenhower kept the United States out of Vietnam in 1954 as the French were collapsing in northern Vietnam. Their colonial war there was going badly, and the French begged the United States to get in. Eisenhower said, “No, we’re not going to do it.” So, we know that he stayed out, and we know what he said at the time, “It’s the wrong war, in the wrong place, for the wrong purposes. We’re not going to go to war to help prop up French colonialism.” He then, though, invested a great deal of prestige and money in building South Vietnam into a democratic country. He believed South Vietnam could be a model to the rest of Asia. So, by 1961, the commitment we had made to South Vietnam was a very significant one. By 1965, when Lyndon Johnson sent hundreds of thousands of troops, the commitment was even greater. It’s difficult to know if Eisenhower would have done the same thing. There’s a good chance he might have because I think he believed what America was doing in South Vietnam was the right thing.

I have concluded that Allen Dulles, who was the CIA director for the entire time that Eisenhower was president, was a pretty dangerous man.… Eisenhower was wary about Allen Dulles, but I don’t think he controlled Dulles sufficiently, and he gave him a little bit too much free rein. So, the CIA became quite reckless. We would learn later, when some of their secret records became available in the late ’70s, just how far they had gone to overthrow governments, plan assassinations, sabotage, and the like. Much of that was known because the Congress started investigating the CIA in the 1970s. But there are a lot of concrete, specific things about how the CIA gathered intelligence, what they knew, especially through intercepts about the Soviet missile program, that we’re only just now beginning to understand.

[There is a great debate as to whether President Eisenhower was aware of the CIA’s activities.] Andrew Goodpaster, one of his closest advisers, always insisted that Eisenhower did not know about it, and he would not have approved it. I’m not quite so sure. I think that Eisenhower did know. I think that his national security adviser late in his presidency, Gordon Gray, kept him informed and they had an understanding not to talk about it. It was a wink and a nod sort of thing. But Eisenhower was unsentimental about these matters. As a lifelong military man, he felt these were bad, bad people, and if national interests required it, he would let [covert operations] go.

The Brown v. Board [Supreme Court] opinion of May 1954 was a huge milestone in civil rights. It told us that the segregation by race of public schools was unconstitutional. Some people thought maybe this was a bombshell that the Eisenhower administration knew nothing about and maybe even was hostile to. But there’s ample evidence that Attorney General Herbert Brownell was working closely with the plaintiffs in the case, shaping the arguments in the court.… They filed an amicus brief in favor of desegregation. They, too, felt it was unconstitutional. So, this was a product of the administration’s policies as much as [of Chief Justice Earl] Warren. Now, Warren shaped the opinion, which was so important, and it was a unanimous opinion. But this is a case where Eisenhower’s reputation has been done wrong. He was often depicted as someone who was against the civil rights movement, or in some ways, a day late and a dollar short. But in that early period of his first term, he and Herbert Brownell really helped the cause. They did significant work pushing the ball forward.

What is interesting about Eisenhower is he blows hot and cold [on civil rights]. We see periods of significant activity, and 1953 and ’54 is probably the period where he’s really pushing. Then, he pulls back and says, “Wait a minute, I have a lot of friends in the South.” And he did. He spent a lot of time in Augusta [Georgia] and thought they should be heard from too—that their views should be taken into consideration. So, he would then try to cool things down. And then, he would pick up again, and there would be a sudden period of activity. And we see that 1957 is such a period of activity—passing the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the [federal] intervention at Little Rock [High School]. After that, 1958, ’59, he’s quite loath to do anything really aggressive on civil rights. So, it’s a picture of a pendulum swinging back and forth.

On press conferences, I think [his record is] quite remarkable. We’ve forgotten that presidents used to be much more available to the press than they are today. A press conference nowadays with the president is a highly scripted thing, it’s very formal; you’re not going to get a lot of mistakes or real news out of a press conference with the president now. The press secretary does it all. Throughout Eisenhower’s presidency, he gave a weekly press conference for about thirty minutes. He stood there and took questions. Sometimes he didn’t know the answer, and he would say, “I’ll look into it. I’ll get back to you.” His press secretary, Jim Hagerty, was right next to him as he was doing all this and occasionally he would pass him a note or two, but Ike was [personally] available to the press.… The press admired him privately, but often in writing their reports they tended to condescend a little bit to President Eisenhower. I think this was part of the origins of the idea that he wasn’t in charge, that he was a lightweight. I think that the [reporters] knew better, but it was a good joke. It became almost a punch line to say, well, here’s old Eisenhower trying his best, but look how he stumbles over his syntax, and so forth. They could be kind of mean.

This sounds like a cliché, but it is true.… It’s a personal characteristic, but it does influence him: he was a world-class card player. Not just a poker player but a bridge player. He loved to keep his enemies guessing, his adversaries guessing, the Chinese especially, and in the Cold War the Russians as well. He didn’t want to go into public and say, “Well, here’s exactly what our policy is,” unless it served his interests. Sometimes it served his interests to say, as in Taiwan, “If there is an invasion of Taiwan, that will lead to war…” because it was a signal to the Chinese. But in general, he wanted to keep his enemies guessing, and who wouldn’t?

The conventional wisdom was that Eisenhower didn’t worry about the missile gap, didn’t worry that the Russians might have had a lot of missiles, didn’t worry about Sputnik because he knew because of the U-2 spy plane that the Soviets didn’t have any big missile program at all. That’s not true. The U-2 spy plane had started in 1955. They started running it over the Soviet Union in 1956. Eisenhower was always very cautious about using it because he was afraid one might get shot down and that would lead to an international incident, which it did in 1960.… So, there were very few U-2 overflights in 1957 and ’58, and even into ’59.… So what they know about the Soviet missile program is incomplete.… To say that, “Well, he just kicked back and said, ‘Don’t worry, there’s no Soviet missile program,’” [there is no] evidence to prove that. The [administration was] actually quite anxious that the Russians were building some major ICBMs that could reach America. It wasn’t until quite a bit later that we got the intelligence that proved that Russians were way behind the Americans.

Eisenhower had some health issues, there’s no doubt about it. He smoked four packs of cigarettes a day when he was in the army in World War II, which means he basically was smoking every moment that he was awake. He quit in 1949, but I suspect it did take a bit of a toll on his health. He had quite a significant heart attack in 1955.… He had a chronic problem with his intestines, ileitis. That gave him all kinds of stomach pain throughout his life. It was finally diagnosed, and they finally operated on that… in 1956, in the summer he was running for re-election. And, he had a minor stroke later in his second term. It didn’t harm him much, but it slowed him down for a couple of days and was a bit of a scare. These things, the mounting strain, the mounting toll of having been the Allied commander and then the president, started to show on him. He lived for ten years after he left the White House, but these were all signs of his constitution, which was very strong, starting to break down a little bit.

He had the first heart attack in Denver, so he spent a great deal of time at the Fitzsimons Army Hospital there recovering. He came back briefly to Washington in the winter. He chaired a couple of meetings and then went to Florida. Basically, he was pretty much out of Washington, out of the White House, for almost six months. He governed [nonetheless]. This is a topic that leads us into the question of his relationship with Richard Nixon. He did not turn over much leadership to Richard Nixon, his vice president. In fact, it was his chief of staff, Sherman Adams, who did a great deal of the day-to-day management of the presidency. It’s odd that he did that, but I don’t think he fully was confident that Nixon could manage the government in his absence. It’s an interesting fact that he didn’t turn over things to him and we didn’t have the succession plan of the Twenty-fifth Amendment yet in place.

In 1956, Eisenhower wanted Nixon to step off the ticket, but he didn’t like to confront people in this way. He didn’t like to fire people. He didn’t want to say, “You’re off the ticket.” What he wanted to do is offer Nixon a cabinet position, maybe in Defense, maybe Commerce, and make him feel as if he was getting some experience so that he could be more of a national figure. He said, “Dick, I think it’s time for you to go and get some real experience running a big executive department. And that way, in 1960, you’ll be a better candidate to be president because you’ll have actually done something instead of just being vice president.” Nixon thought about this and said, “Well, Mr. President, are you asking me to get off the ticket?” And Ike said, “Oh, no, no, I want you to get experience. I want you to be president one day.” He couldn’t fire Nixon. He couldn’t direct him to do it. He just offered him the opportunity. They did a two-month back and forth on this. Nixon didn’t want to leave the vice presidency because he knew it would be perceived as a demotion. He knew it would be perceived as having been dumped; he was very sensitive about not being taken seriously by Eisenhower. Nixon refused to accept the cabinet position. He said, “Mr. President, I will not go to the cabinet. If you want me to be off the ticket, just say so, and I’ll step down.” Ike wouldn’t do it, so they went back and forth in this very curious way. Finally, Eisenhower gave up and said, “All right, well, you tell me your decision, Dick.” Dick said, “I would like to stay on the ticket.” And Eisenhower said, “OK.”

[Eisenhower and Nixon won in 1956 by a landslide, carrying forty-one states to Democrat Adlai Stevenson’s seven.]

… [Toward the end of his administration] Eisenhower and Allen Dulles did plan what became Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs Operation. There’s no doubt about it. We have a great deal of evidence showing that it was a yearlong process—thinking about how to invade Cuba with a group of Cuban exiles from Guatemala and overthrow Castro. But Eisenhower didn’t pull the trigger on the operation. The reason is that it wasn’t ready to go. It wasn’t big enough. It wasn’t strong enough. Eisenhower himself hadn’t really done the careful planning that would have made it, potentially, successful. When Kennedy gets into office, he launches it right away. It fails. He invites Eisenhower to Camp David the next day, and Eisenhower says, “Well, did you do all these things: Did you ask all the tough questions? Did you go through the logistics? Did you go through the planning?” Kennedy says, “I just took the advice of the generals.” Eisenhower says, “Well, that was your first mistake.” Kennedy always resented that Eisenhower gave him this plan, in a sense, but then didn’t take responsibility for it, which perhaps he should have done. But Eisenhower’s view was, “You’re the commander in chief, it’s your job to ask the tough questions. If it fails on your watch, it’s your responsibility.” And, of course, publicly, Kennedy did take responsibility for it.

Eisenhower was very angry that John Kennedy [and not Richard Nixon had] won the 1960 election, no doubt about it. Kennedy had criticized Eisenhower in the campaign. Kennedy had said terrible things about Eisenhower. But by 1960, Eisenhower was a much more seasoned politician; he knew it wasn’t personal. What he wanted was a good handoff to the new president. They met twice before the inauguration, and each time they met for a long time. They talked through world problems; they really discussed what was going on. Eisenhower said, “Look, it’s a tough job, and I want to help you any way I can. Here’s what I learned on the job. Here are a few pointers.” Kennedy came away very impressed with Eisenhower every time he met him. He realized this man is a serious figure, which is not what Kennedy had said about him on the campaign trail. He’d said, “Oh, he’s such a dummy; he’s such a dunce. He’s asleep at the wheel.” But when he met him in person, he realized what a significant figure Ike was.

[Eisenhower’s farewell address continues to be quoted today.] Isn’t that interesting that a man stepping down wouldn’t crow about all of his achievements but instead say, “There’s still work to be done. I’ve left one big thing undone.” The tone of that speech is a warning, which is that we’ve had to build the military-industrial complex in order to protect our freedoms. He said, “I regret we had to do that, but we have done it. We’ve created this enormous military power based on nuclear arms.” And he said, “We now have to control it. We would love to get rid of it completely, but unfortunately the Russians won’t let us. They’re just as aggressive and dangerous as ever.” He was saying, essentially, his preference would be total global disarmament. His preference would be peace. But he hadn’t achieved that. What he had achieved was creating a defense system that would protect America, but it wasn’t the same thing as world peace.

I spent the bulk of the time researching this book in Abilene, Kansas, at the Eisenhower Presidential Library.… Abilene is really where you have to go, not just because that’s where Eisenhower’s papers are located, the private papers, but because that’s his hometown. The more time I spent in Abilene and the more time I spent in Kansas, the closer I felt I was getting to this man. He was a very famous, very successful, worldly cosmopolitan figure, but he really was from Kansas, and he never forgot it. He talked about it a lot. Getting to know… the town, feeling the landscape—which is so different from the East Coast—I started to get a read on this man.

He was a great internationalist. He believed firmly in the so-called free world, the free nations of the West, working together, working out their problems. [He believed] in displaying [collective problem solving] at the United Nations to the nonaligned, the newly independent nations of the world—all of those states that were just getting their independence in the 1950s—that this is how democracy works. He believed that the great states can come together at the United Nations and work out their problems together. He’d been the great coalition builder in World War II, and he was enormously effective at listening, hearing other people, working out problems. It showed in the coalition in World War II. He loved the UN for that very reason. It was, in a sense, a projection of American democracy on the world stage.

One thing I can say about Eisenhower is that the scale and scope of the US government, and, indeed, of the United States, was a bit more manageable in the mid-fifties than it is today. So, while I think Eisenhower can teach us some basic things about governance, and about humility, and about generosity, and kindness, moderation, the US government has just become so big. It’s so difficult for any one president, no matter how gifted, to be in complete command. So, I think that it’s dangerous to say, “Well this president is exactly what we should have today.” But, we can be inspired by a character, and the character of experience, the character of knowing where you come from, the character of generosity, humility—those are things that Eisenhower had.