JOHN F. KENNEDY

35th President, 1961–1963

Historian: Robert Dallek

Presidential historian Robert Dallek is also a lecturer at Stanford University’s Stanford in Washington program. On January 2, 2014, he discussed his book, Camelot’s Court: Inside the Kennedy White House, on Q & A.

Presidents come to office initially on a wave of enthusiasm and excitement, even if they’ve only won by the narrowest of margins, which was true with John Kennedy. He won by a sliver, and yet very quickly, he gained popularity and approval from the public.

What I find so interesting with John Kennedy is that during [the fiftieth] commemoration of his assassination, he had a 90 percent approval rating.… The question any historian has to ask is, why is this the case? After all, he was there for only a thousand days. His was the seventh briefest presidency in American history.

The answer is that, on the one hand, people don’t much like his successors: Johnson with Vietnam, Nixon with Watergate, Ford’s truncated presidency, Jimmy Carter’s presidency, which people see as essentially a failure. The only one is Reagan. The two Bushes don’t register that powerfully.… Bill Clinton, yes, but he had the Monica Lewinsky affair—the only elected president in the country’s history to have been impeached. It’s a black mark against his record. Kennedy, of course, dying so young at the age of forty-six, having only been there for a thousand days, it’s a blank slate on which you can write anything. And he was so young. The country identifies with that. They have a sense of loss to this day over his assassination, but he gives people hope. What they remember are JFK’s words: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country”; or, his famous peace speech at American University in June of 1963 in which he said to “think anew” about the Soviet Union. He and Khrushchev had come out of that Cuban missile crisis—a nuclear war so much on the horizon—both frightened and terrified by that experience. As a consequence, Kennedy wanted to move towards some kind of détente with the Soviet Union, and Khrushchev was receptive to that. That’s how you got the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty signed in the summer of 1963. It happened very quickly. They had been hustling over that for years, and suddenly it occurred.… If Kennedy had lived, we would see the talks with the Soviet Union more quickly than it came about with Richard Nixon.

I love the anecdote that when JFK was first elected, Bobby Kennedy asked [historian] Arthur Schlesinger if he would like to be an ambassador. Schlesinger said, “No, Bobby, if I do anything, I’d like to be at the White House.” A few days later, Schlesinger saw the president-elect, who said, “So Arthur, I hear you’re coming to the White House.” Schlesinger said, “I am? But what would I be doing there?” Kennedy said, “I don’t know, Arthur. I don’t know what I’ll be doing there, but you can bet we’ll both be busy more than eight hours a day.” The point is JFK understood that being president was not a set-piece affair. He evolved, and he grew in that office. That, in many ways, was his greatest strength: Kennedy grew in the office.

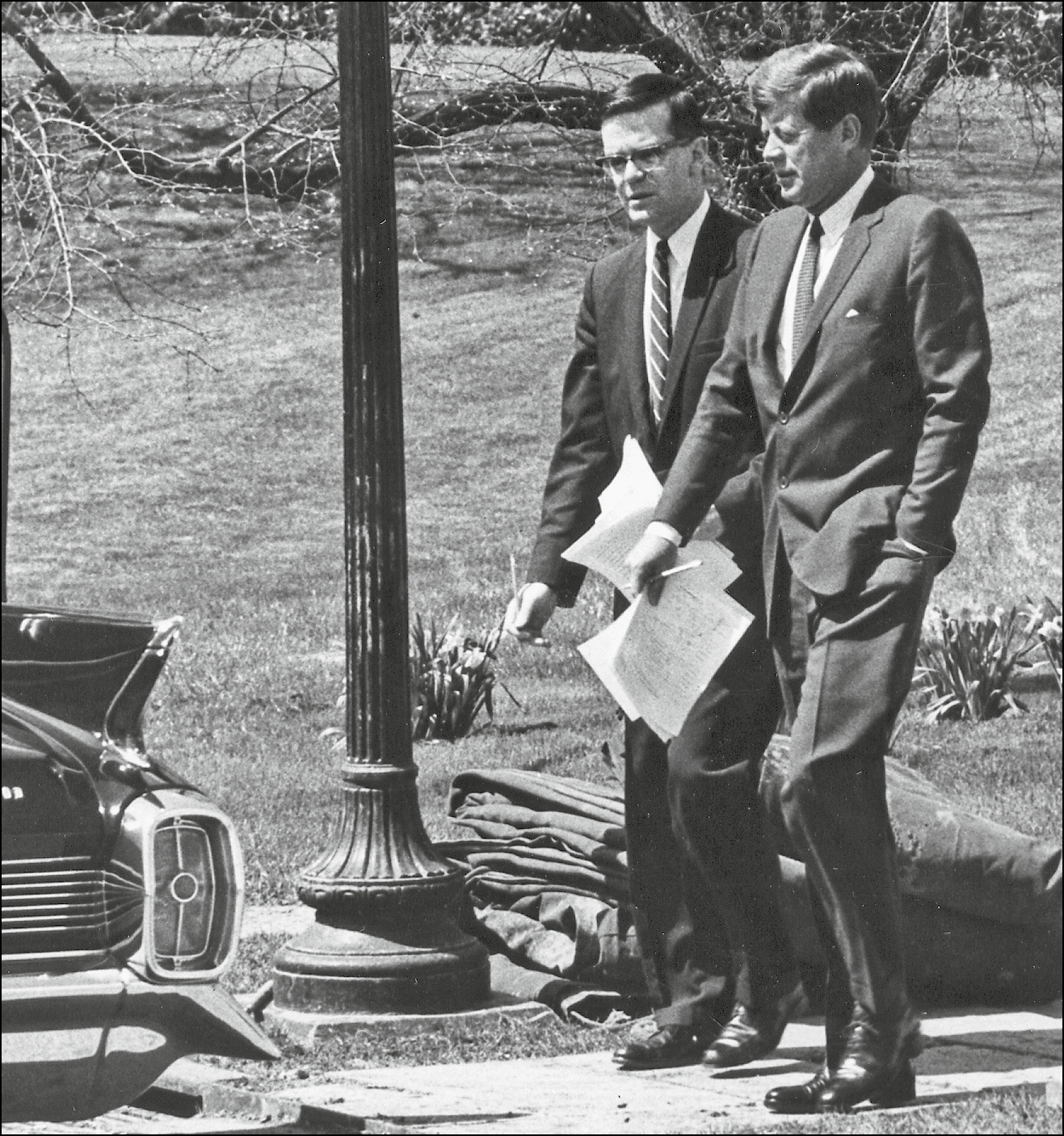

[Kennedy’s 1957 Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Profiles in Courage, is an important part of his biography. It’s authorship is] a complicated story. He did write part of it. There were others who contributed. My research told me Kennedy would listen to tapes of the transcripts of the chapters, and he would edit them; so, it would be unfair to say that Kennedy was the sole author of Profiles in Courage. On the other hand, it would be unfair to say that he didn’t have anything to do with it or had a ghostwriter do it because he was vitally involved. So, it was a combined effort, so to speak. But I think Mrs. Kennedy was a bit jealous of Ted Sorensen maybe trying to take too much thunder and too much credit. These are complex relationships that spring up in these White Houses. Ted Sorensen was the president’s wordsmith. He was a brilliant speechwriter. He and Kennedy had a kind of symbiotic relationship. I don’t mean they were friends. I don’t mean that they socialized, because they didn’t have that kind of relationship. But there was a kind of intellectual exchange between them and a kind of intuitive understanding of where this president wanted to go in his administration and what he wanted to say. Sorensen had the gift of being able to translate that into a language that is memorable. After all, some of Kennedy’s speeches are going to last, going to be remembered.

[My research and writing also details JFK’s serious health issues. John Kennedy had health problems, including Addison’s disease, a possible fatal malfunctioning of the adrenal gland. He had chronic back pain that had led to major unsuccessful surgeries, spastic colitis that triggered occasional bouts of diarrhea, prostatitis, urethritis, and allergies that added greatly to the normal strains of his nationwide campaign in 1960.]

[After Kennedy died,] there’s no question that Ted Sorensen was the keeper of the flame.… There was a three-man committee that controlled JFK’s medical records, and [by 2002] two of the members signed off [on opening them up]; Sorensen was reluctant to do it. I went to see him in New York, met with him in his residence, and persuaded him to let me have access to the records. He didn’t know what was in there, and when the records came out, the New York Times ran a front-page story about my findings and Atlantic magazine published an article about my book and on Kennedy’s medical history. Sorensen was angry. When he’d see me, which was a few times after that, he’d say, “There was no cover up.” But, of course, there was. They were hiding from the public the extent of Kennedy’s medical history and difficulties. If people knew how many health problems Kennedy had, I don’t think he even would have been elected in 1960—however unfair that may be, because he comported himself brilliantly during the presidency. I set his medical records down alongside the timeline of the Cuban missile crisis with the [White House] tapes we had. There were no concessions to his medical difficulties during that crisis. Now, [we have subsequently learned] it was medications that helped him get through it without stumbles.

[After these stories came out, Ted Kennedy and Arthur Schlesinger concluded] that my description of Kennedy’s health problems enhanced, rather than undermined, his public standing, his reputation in history. How he managed to rise above his health difficulties and be an effective president was a very impressive achievement, and so they would take it with that. But, even Ted Kennedy did not know the full extent of his brother’s health problems, and it is the measure of how much they hid it—Joe Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, the president himself, and Jackie—they were the ones who knew, but it was largely hidden from the world.

[In the years after JFK’s death, the public also learned about John Kennedy’s womanizing while he was in office, which his White House press corps did not cover.]… I interviewed a number of journalists for my [2003 Kennedy] biography and asked them, “Did you know that Kennedy was womanizing?” They said, “Yes, we always suspected.” “Why didn’t you write about it?” “We didn’t do it in 1960s; you didn’t intrude on the president’s private life in that way.” And so, [Kennedy’s womanizing] was hidden from the public.

When I first published my book and the story came out about [Mimi Beardsley, a nineteen-year-old intern with whom Kennedy had an ongoing affair…], I heard on the grapevine that a publisher offered her a million dollars to write her own book, a memoir. It wasn’t until about eight years later that she finally did it. I never asked her why… she did it. Maybe she needed the money. I suspect [the tabloids] would have still been willing to pay her because it really was very much a tell-all book, and some of the details she reveals are somewhat shocking.

There are two ways you can look at this. On the one hand, it didn’t have an impact on his conduct in the presidency, as far as I can tell. Was he going to be found out, was he going to be impeached? Not in 1962, ’63. The… mainstream press, did not write about the president’s private life in that way. But it says something about the man’s character, about his personality, about the fact that there was some kind of deep-felt neediness that this man had, that he had to seduce this nineteen-year-old young woman. And it was not just [seducing her], but her description of some of the things that went on, that he encouraged her to give oral sex to Dave Powers, Kennedy’s principal aide, and to his brother Ted. She resisted when JFK suggested that she perform oral sex on Ted Kennedy. But with Dave Powers, she did it, and she said that Kennedy watched. He later apologized to them. But, what word can you apply to this? Perverse.

The journalists I talked to, including [the longtime conservative columnist] Bob Novak, said they suspected. They had clues. They thought there were lots of women coming and going from the White House. In my first biography, a journalist told me the story that when Kennedy was on the campaign trail in 1960, he was in northern California, and there were [a] bunch of pompom girls from the local college. Kennedy points to one of them via his aide. He went up to this young woman and said to her, “The senator would like to see you in his hotel room.” She went up there. The story the journalist told me… is that Kennedy looked at his watch and said to this young woman, “We have 15 minutes.” What happened after that, the journalist didn’t say. But the point is, sure, the reporters knew; at least they suspected [what was going on].

… In this day and age, it seems to me that it would be madness for a president to try and do this [in the White House] because it’s a different world from what it was in the 1960s. It would be brought forward; it would be all over the press, all over the television, and probably destroy the man’s presidency. But it was a different time in the 1960s. I’m not justifying it. It was terribly excessive, what he did with Mimi Beardsley.… On the other hand, I’m not a Puritan, and I’m not saying that, “My god, he should have just been loyal to Jackie.” That was between them. Jackie knew about this; she knew he was a philanderer. There was an anecdote that the first couple was up in Canada, and they were in the receiving line standing next to a White House military aide. And [the first lady] said to him in French, this man understood French, “It’s not enough that I come to Canada and stand in line?” One of these [young women] was in line to shake her hand, and she was furious at this situation. And who can blame her?

Kennedy was badly burned by the Bay of Pigs experience [in April 1961]. He had listened to the experts—the CIA, Joint Chiefs of Staff [and the operation failed]. Soon after, he went to see President [Charles] de Gaulle in France. He did that trip in May–June of ’61. De Gaulle said to him, “You should surround yourself with the smartest possible people, listen to them, hear what they have to say. But at the end of the day, you have to make up your own mind.” And Kennedy also remembered what Harry Truman had said, “The buck stops here.” After the Bay of Pigs, he was absolutely determined to make up his own mind, hear what these experts had to say, weigh what they were telling him. But at the end of the day, he was going to make the judgment, and he was the responsible party. That was abundantly clear when you read the transcripts of all those tapes during the Cuban missile crisis [in October 1962]. He was his own man. He was the one who was making up his own mind. He held the Joint Chiefs [Chairman] Maxwell Taylor at an arm’s length; the chiefs wanted to bomb, invade, and Kennedy didn’t want to do it.

John F. Kennedy was very critical of the Joint Chiefs. Maxwell Taylor began with a kind of cachet because he was Kennedy’s guy, and Kennedy made him the chairman of the Joint Chiefs. But over time… Taylor so much reflected what the [other] service chiefs were saying during the Cuban missile crisis and subsequently about Cuba… that Kennedy became skeptical of him. I don’t know that Taylor would have lasted that much longer into a second term. There’s an anecdote that after the Cuban missile crisis was ending, Kennedy held the Joint Chiefs at arm’s length. He brings them in, and they say to him, “Mr. President, you’ve been had. Khrushchev is hiding missiles in caves.” And, they leaked this [to the press].… Khrushchev wrote Kennedy a note saying, “I don’t live in the caveman age, and that means I’m no caveman.” But the Joint Chiefs still talked about the need to plan bombing and an invasion [of Cuba]. Kennedy said, “You can go ahead and make plans because you never know what’s going to happen.” And, of course, they make all sorts of contingency plans. Part of that plan was to drop a nuclear weapon on Cuba; Kennedy thought this was crazy.

The chiefs told him that all the collateral damage [of dropping a nuclear bomb on Cuba], in essence, could be contained. What that would have done to the south coast of Florida, let alone to Cuba—which would’ve turned into a pile of rubble. And so, Kennedy thought they were kind of mad. But, giving them their due, one has to recall that the Joint Chiefs came out of World War II, and they remembered fighting Hitler, Mussolini, and the Japanese military, who fought to the bitter end. Their attitude was “bomb them back to the Stone Age,” which is what they did in Germany and Japan, with the fire bombings of Tokyo, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings. So, this was their attitude. Thomas Power, head of the air force, had said, “What are all these concerns about nuclear weapons? If at the end of that war with the Soviet Union there are three Americans left and two Soviets, we’ve won.” So, [Kennedy was dealing with] this kind of [attitude among the chiefs].

I knew [Kennedy’s defense secretary Robert] McNamara a little bit. I interviewed him a couple of times. The first time I interviewed him [was prior to 1988, and] I began by asking about Vietnam.… Within fifteen minutes, all he could talk about was Vietnam; he was profoundly conflicted. During the Kennedy presidency, he was the biggest advocate of exercising muscle in Vietnam, asserting the authority of power. With journalists like David Halberstam who raised questions with him, he was dismissive, even contemptuous. So sure, McNamara eventually came around to the proposition that this was a military no-win situation in Vietnam, but he had been so arrogant about leading us into that war. I think that’s what agitated him so much.… He eventually got out of the Johnson administration because Johnson saw him having almost a nervous collapse over his struggle over Vietnam. They sent him off to be president of the World Bank. McNamara was a man who was profoundly conflicted, but only over time. He was one of the architects of expansion of a larger war in Vietnam.

The biggest [advocate for Vietnam acceleration on Kennedy’s team] was Walt Rostow. Rostow became Lyndon Johnson’s national security adviser. Rostow, during the Kennedy presidency, was already talking about bombing Hanoi and Haiphong and putting ground troops there; and Rostow never gave up on that war. I knew Rostow, as well; talked to him, interviewed him,… and his attitude was, “We saved the other Southeast Asian countries. We gave them time to develop.” That was his rationale [for prosecuting the Vietnam War].

Dean Rusk was Kennedy’s secretary of state. Rusk [made the decision to] replace [JFK’s undersecretary of state] Chester Bowles, who Kennedy didn’t like having around and was trying very hard to get rid of. Finally, Rusk had to send Bowles on a mission around the world.… He replaced him with George Ball, who was much more of a team player. On the other hand, behind the scenes, Ball was candid with Kennedy about Vietnam, in particular. He told him at one point, “Mr. President, if you put two or three hundred thousand ground troops into those jungles of Vietnam, you’ll never hear from them again.” Kennedy said to George Ball, “You’re crazy as hell,” meaning, I believe, that, “I’m never going to do that.” We will never know exactly what Kennedy would have done about Vietnam.… I don’t think Kennedy ever would have done what Lyndon Johnson did in Vietnam; I don’t think he ever would have put in 545,000 troops.

Dean Rusk’s personality was such that it was very deferential to the president on making foreign policy. But I think there’s a mixed assessment [of Rusk’s effectiveness] in the sense that this is what Kennedy wanted. He didn’t want a secretary of state who was going to vie with him and compete on the making of foreign policy.… The Kennedy administration was a foreign policy administration. Kennedy was very much a foreign policy president, and I don’t think JFK wanted a secretary of state who was going to be aggressive about challenging what he wanted to do in the conduct of it. What Kennedy complained about was that Rusk didn’t have ideas; he was not someone who came forward with suggestions that Kennedy might have used, that he had little imagination in dealing with the foreign policy. And that was a legitimate complaint.

… I think Kennedy felt a certain amount of guilt over the fact that [South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh] Diem was assassinated [in a CIA-backed coup in November 1963] because he said privately, “Listen, whatever his failings, he had led his country for quite a few years and done constructive things and was a bulwark against the communist takeover.” Kennedy was reflecting on his own recriminations about having allowed such a coup to take place. He was also [expressing] the concern that the United States was now going to have to take greater responsibility for Vietnam than it had taken in the past. Kennedy was keen to get out of Vietnam. He had a conversation with [National Security Administration senior aide] Mike Forrestal the day before he went to Dallas, Texas, and said he wanted when he returned a full-scale review about Vietnam, including the possibility of getting out.… I don’t know what he would have done. I don’t think he himself knew what he would have done.

… [As president,] Kennedy was not that interested, initially, in domestic affairs. He was dragged, so to speak, kicking and screaming into dealing with civil rights. When he dealt with it, it was quite courageous of him to put that Civil Rights Bill before the Congress in 1963. It could have jeopardized his re-election, since he knew he was going to be alienating Southern states and Southern voters, and they had put him across [the finish line in] 1960. He didn’t know he was going to run against Barry Goldwater; he thought he might well be running against him, but he didn’t know for sure. And so, it was courageous of him to do that. He felt that the time had come [to advance civil rights. So, I contend that] Kennedy grew, he evolved in that office, but he was very much a foreign policy president.