WILLIAM J. CLINTON

42nd President, 1993–2001

Historian: David Maraniss

David Maraniss is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and associate editor for the Washington Post. He was interviewed on March 27, 1995, on C-SPAN’s Booknotes for his book, First in His Class: A Biography of Bill Clinton, which details his years on the road to the White House.

I thought Bill Clinton was a great story. That was really the underlying motivation [for my book], that whatever anyone thinks of Bill Clinton’s presidency or his ideology, his life is a great American story. It’s a narrative that I thought revealed a lot about ambition, and the clash between ambition and idealism—[his] coming out of nowhere, dealing with a troubled family, rising out of Arkansas from the point where he shook John Kennedy’s hand in 1963, to actually living in the White House himself. That’s just a great story.

Bill Clinton’s early childhood… is probably the least-known part of his life and the part I had the most frustration trying to recreate—starting with his birth and up through probably his first ten years, dealing first with a young man without a father and then an alcoholic stepfather. Although I got a lot of people talking about that part of his life, I really don’t know what it was like for young Bill Clinton to be in that household and I thought I’d really like to see how it affected him.

I moved to Hope, Arkansas, where he was born, and spent a few weeks there interviewing dozens of people who knew the family. I talked to a lot of his aunts and got a lot of the letters of that era and tried to recreate what it was like in that small town in the South during the late 1940s and the early 1950s. Then I moved up to Hot Springs, where his stepfather was from, and stayed in the same hotel that Al Capone used to hang out in, the Arlington Hotel up there, and tried to talk to as many women of his mother’s generation—many of whom also dealt with the same problems that she did in terms of [not] being treated as equals with men and being abused by their husbands. So, I spent a lot of time trying to recreate that generation.

Essentially, he had two mothers. His own mother, Virginia, had left Hope when he was less than two to go down to New Orleans to study to be a nurse anesthetist. And so, he lived with his [grandmother Edith] “Mama Cassidy,” who was a very rigid character. Bill Clinton is such a contrast of people; he has a certain discipline, and yet he’s very undisciplined. His discipline comes from that grandmother, who would wake him at a specific hour, whether he was ready to awaken himself or not, and fed him constantly on a pattern. So, he had two mothers, one mother who was sort of rebelling against the life in Hope and wanted to get away from it, and this grandmother who was teaching him the discipline of that time and place.

Many of their relatives told me the stories of how Mrs. Cassidy would scream and yell at her husband, Eldridge Cassidy, who was probably the best-liked man in Hope. He was the local iceman at first. He would deliver ice on a horse and wagon and then eventually got a truck. But he was known as a very, very friendly man, and she thought he was too friendly with some of the women in town and would let him know.

His [maternal] grandparents didn’t have a lot of money, but they weren’t poor by Hope’s standards. They certainly weren’t rich; his grandfather never really cared about money, but he did run a store, and [Bill] lived in a nice white house. So, I wouldn’t say that’s poverty. Roger Clinton, his stepfather, was terrible with money and was always losing it—wasting it on alcohol and women and gambling. Roger Clinton’s brother, Raymond Clinton, was a wealthy auto dealer in Hot Springs and belonged to a country club, and young Bill Clinton had a car in high school and played golf at a country club. So, I wouldn’t say that that’s poverty. I think [the stories that Bill Clinton built himself up from a life of poverty is] a little bit of the Clinton mythmaking.

[Virginia’s] first husband was Bill Blythe, who is Bill Clinton’s biological father, most likely. It’s a very sensitive subject. But in my book, you’ll notice that the time when Bill Blythe got out of the military in World War II does not quite correspond with the point in time that Virginia, Bill’s mother, always claimed that he got out of the military. So, there’s some question about when Bill Clinton was conceived. I had never heard that before. I heard it from people in Hope who would raise questions about it. I’m not trying to disparage Bill Clinton’s mother, but as a historian I had to look into that, and, unfortunately, I wasn’t able to totally resolve it. But there are some discrepancies on the dates. Bill Blythe had been married at least four times before he met Virginia Cassidy. She knew about none of those marriages. And, it’s possible that there were even one or two others. It was hard for me to trace them all out throughout the small courthouses of the South.… I went to six courthouses: in Madill and Ardmore, Oklahoma; Oklahoma City; Sherman, Texas; in Shreveport, Louisiana; and in Texarkana. I found five [marriage records]. I was looking for W. J. Blythe—that’s the way he was known. I was looking for divorce and marriage records and birth records.

Virginia had never been married before. When she did marry, she first married Bill Blythe, and then she married Roger Clinton; then she married Jeff Dwyer, and then she married Dick Kelly. So, she’d been married to four men, but five times. She married Roger Clinton twice. Roger Clinton married Virginia when Bill Clinton was four years old, and they divorced when Bill was fourteen, fifteen, but only for three months.… She didn’t love him anymore. He was an alcoholic who had abused her. Their divorce records are full of cases: one time he took her high heels and beat her on the head with them, and he accused her of a lot of things which were untrue. It was not a very comfortable marriage, but she remarried him because she felt sorry for him.

I think young Bill Clinton saw a lot [of violence growing up in Roger Clinton’s home]. That’s not to say that every day in that household was a terror or that it was terrifying. I know from recreating Bill Clinton’s life through his letters and conversations with some of his friends that it did not dominate the exterior of his life. His friends didn’t even know that his stepfather was an alcoholic or abusing his mother, but I think that there were many occasions when it got pretty nasty inside that house. And, I think that’s what drove him in a lot of ways.

… Bill Clinton was in constant search of father figures. He never had a father, and I think that later in his life it was his minister in Little Rock, W. O. Vaught, who was as unlike Bill Clinton as anyone could be in the world. He was a short, wiry, bespectacled, rigid man who taught only from Scripture, was very conservative in his political beliefs, but ran the largest Southern Baptist church in Arkansas. Bill Clinton took to Vaught and really looked to him not only for spiritual help but political advice. Vaught helped him work out his positions on abortion and the death penalty, but Vaught died before Clinton ran for president, and I think he missed him a lot during that tumultuous era.

Bill Clinton’s whole life has a measure of calculation in it, which he has tried to diminish for a lot of reasons, one of which is that raw political ambition in America is often seen as a bad thing. You would never say that about someone who wanted to grow up and become the best ice skater in the world or the best pianist, but, if you wanted to become president at an early age, people would see that as a negative. And so, he always wanted to couch that, even though he had that burning desire in him. Part of the way to temper that [image] is to make it look like a lot of those things happened by accident. The prologue in my book is his handshake with John Kennedy in 1963, the iconic transfer of ambition from a president to a future president. As my prologue shows so clearly, that was no accident, that handshake. He was the one on the bus ride down [with other Boys’ Nation participants] who kept asking the chaperon whether they could get pictures taken, and once the bus got to the White House, he race-walked his way to the best position in line to get the handshake. So, there was always that calculation.

[Bill Clinton graduated from Hot Springs High School in Arkansas and was accepted into Georgetown University in Washington, DC.] The watermelons of Hope, Arkansas, [also became part of Clinton’s image-making]. He used to describe how the railroads would come through Hope in southwest Arkansas and stop there. The porters would get out, and there’d be fresh watermelons cut on these trays outside the train, and they’d bring them back, and the people would eat them on their way back to Texas. It was a way for Bill Clinton to talk about that he was from a place other than where his friends were from. He left Arkansas when he was seventeen years old, went to the East Coast, and was away for nine years, and he was dealing with a totally different culture. He was the Southern Baptist at Georgetown University, full of upper-middle-class Catholic kids from the East Coast. The sons and daughters of presidents of El Salvador and Saudi Arabia and the Philippines were in his class. Unlike so many of the kids of that era who would try to forget their past, shed their past, Clinton used that past almost as a defense mechanism. Rather than being embarrassed about coming from a small town, he played it up. One way he did that was by constantly talking about the watermelons.

He was never first in his class academically, but he was close. He was fourth in his high school class; he was Phi Beta Kappa at Georgetown. At Oxford he never got a degree, and at Yale Law School he graduated with the law degree, but he was never in class. But [my book’s title], First in His Class, means that he’s the first member of his generation to become president.

[Bill Clinton was out of sorts his second year as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford in 1969, because of] the draft, largely. About half of the thirty-two Rhodes scholars went to England their first year with sort of unofficial, but clear, Vietnam War deferments that they didn’t deserve. President [Lyndon] Johnson had just eliminated graduate school deferments, but most of the local draft boards considered these guys local heroes, and they didn’t want them to get drafted right when they’d won this great prestigious honor. So, they went over to England with deferments that they didn’t really deserve. And in the spring, finally, of his first year, Clinton got his draft notice. He came back to Arkansas that summer of 1969 in agony trying to figure out what to do. He didn’t want to fight in Vietnam. He was against the war. Who knows whether he was afraid of dying, but I think most young men are. There’s a whole mixture of feelings that he was going through. He wanted to be in politics. He believed in the established way. So, he was trying to figure it out, and he eventually manipulated his way into an ROTC post that he never served in and went back to England feeling guilty about that.

[His next stop was Yale Law School. When he was there, he made a point of sitting with the black students at their table.] It was at a time of black power, black separation to a certain degree, or at least a cultural identity that separated the races in college campuses. Clinton’s friends, his roommates, all told me they were afraid to go sit at that table, even though they were, perhaps, further to the left politically than Bill Clinton. They just said they were uncomfortable being over there, and it was clear to them that the black students didn’t want them to be there. Clinton just sort of barged his way into the table and would tell jokes about himself, self-depreciating jokes, jokes about the South, jokes about sex, jokes about anything. He really was very comfortable in that milieu, just a natural thing that he had. He is very good at adapting to different cultures and milieus and is particularly good at connecting with black people on that level, and almost every black person that I had interviewed for the book told me that in one way or another.

I found that in almost every era of Clinton’s life, there’s at least one story that had become mythologized. Sometimes it’s totally innocuous, and it’s just probably bad memories.… Sometimes there was definite psychological or political reason for the mythologizing. For instance, another one of the myths that Bill Clinton would tell was about how he accidentally got his job as a professor at the University of Arkansas. He says he was just driving back from Yale Law School and stopped at the side of the road on the interstate and called the dean and got the job. In fact, he had tried to get the job for many months and had gone through the normal patterns of using friends and contacts to get that job. I think that that myth was established by Clinton because he was going back to a place that all his Yale Law School friends thought he was crazy to go to. And so, [in his retelling] it was sort of like, “It was just easy; it was an accident. I didn’t try to do it.” The reason was that he knew in his mind he was going back to Arkansas to run for Congress; and so the idea that he had worked so hard to get hired as a professor when, in fact, he had really not much interest in being a professor—that’s why he would create this myth that it was just sort of a fluke.

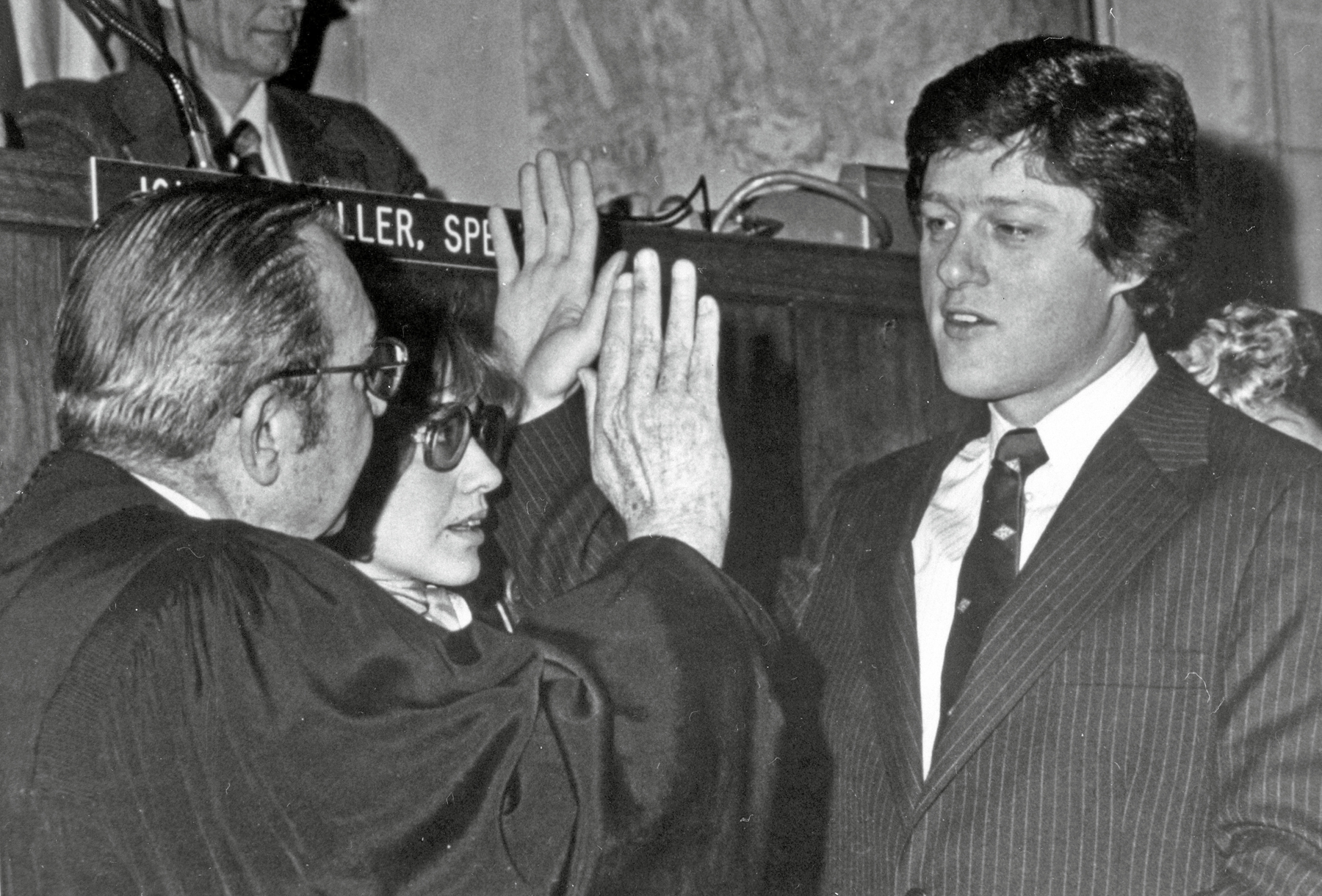

[At age] twenty-seven, Clinton is running for Congress in Fayetteville, Arkansas. He had just moved back from Yale Law School to be an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. In 1974, he was running against [Republican incumbent] John Paul Hammerschmidt, his first race there—which he did well in, but lost. [Two years later he was elected Arkansas’s attorney general and then ran for governor in 1978.]… In 1979,… he was inaugurated as the youngest governor in America since Harold Stassen; Clinton was then thirty-two.

[The relationship between Bill and Hillary Rodham Clinton, whom he married in 1975, is] always changing. I think that it was built on a shared passion for policy and politics and books and ideas and intellectual life, and also a sense of humor. When he married Hillary, he told his friends that he was going for brains over glamour. I think that she knew what she was getting into when she married him, in the sense of his enormous appetite for life. They’ve had several tumultuous parts to their marriage, but it’s a pragmatic, political partnership with some extra spice to it as well. Absolutely.

To understand their relationship, you have to understand it’s gone through… stages, basically. They met at Yale Law School, and from that point in the early 1970s until 1980 when he was defeated as governor, although they saw that they could get to their ultimate goal together, they were really leading independent lives in the sense that she was building up her own life and career. [She worked] first as a law professor and then as a lawyer and then working in Children’s Defense Fund issues. Then he got beat, and she came to the realization that he could only recover with her more profound help. From then on, she was his key financial person, his key political adviser, his pro bono lawyer on ethical issues, and his main policy person. [He won back the governorship in 1982 and Hillary became] the head of his task force on education reform, which was successful, and which made his name in Arkansas. This established his career for the 1980s and helped him become a national figure. They carried that policy partnership into the White House almost without even thinking twice about it, and so then when the [Clinton administration’s] health care plan was defeated, it forced them to reconsider whether she should be in that out-front policy role [as first lady].

[Political consultant Dick Morris has a key role in the Clinton story.] It was 1978, and Clinton was attorney general of Arkansas, and he was preparing to run for governor. Morris was really starting out in his career and was very aggressively pursuing candidates around the country. Clinton was one of those that he latched on with, but he drove Clinton’s other aides crazy during that first campaign, and they essentially fired him until Clinton was fired as governor after only two years. Then Hillary called and said, “Come on back. We need you again.” Then Morris stayed on for the rest of the ’80s.

Dick Morris’s advice was often very astute, and that’s why Clinton, and even more so Hillary Rodham Clinton, really relied on Morris. [After Clinton lost his re-election bid in 1980,] Morris is the one who told Clinton to apologize to the people of Arkansas for his first term. It proved to be very effective saying that he understood that he’d made mistakes, almost like the prodigal son saying, “Let me back.” It worked very effectively, and it was a technique, a sort of humble admission, that Clinton and Hillary remembered for the future and used again and again over the years.

This happened in 1981 when he was preparing to run again in’82. They taped a TV spot where Clinton essentially said, “I’m sorry. I learned my lessons. It will never happen again.” At that point, Clinton was the youngest ex-governor in American history. He was really depressed; he fit that ironic description of the Rhodes scholar, which is a bright young man with a future behind him. Morris really pulled him out of it and told him, “Apologize; go forward.” It worked. And then he developed what I call the “permanent campaign,” which was essentially to go around the established media, the newspapers, and television; as you’re pushing your legislative agenda, use your own public relations apparatus to sell your agenda. It’s something that Clinton did from then on, to use polling constantly, not just to find out what the people were thinking about an issue, but how they would respond specifically to rhetoric. Clinton loved that. It isn’t just pure Machiavelli. Clinton really did love to connect with people—he always had—and to have a scientific way of doing it really intrigued him. And he did that for the rest of his career as well.

[Longtime aide] Betsey Wright came down to Little Rock about a week or two after Bill Clinton was defeated in 1980. She lived in the governor’s mansion for a while, piecing back together all of the detritus of his life, of his political career. She put into computers all of the thousands of note cards that he had of his key political allies and contributors. Then, when he won re-election, she became his chief of staff from 1983 through 1990. Her relationship with Clinton is one of the most interesting that I encountered. There’s a real sisterly-brotherly, love-hate relationship going on all through their time together. She is both fiercely loyal to him and yet is angry at him all the time.

… There’s a scene in [my] book where Betsey Wright and Bill Clinton meet at her house, and they go over a list of the women who might be problematic for Clinton if he were to run for president in 1988. When the book came out, she issued what I call a non-denial denial, saying that David Maraniss might have “misinterpreted what I had told him.” But I hadn’t; she knows I didn’t. It’s very clear to me and my editors at the Washington Post that for two weeks before that incident I’d read to her all of the parts of the book that referred to [his sexual interactions with women]. We have documents about it. I don’t think Betsy Wright was mad; I think she was under a little bit of pressure to try to deny it, but no one has said a word about it since, or challenged any of the other parts of the book.

… Clinton has always considered himself an education politician, and he has so many degrees himself, but he was under court pressure to reform the education system in Arkansas. To get the money that he needed—he realized through polls that Dick Morris did and through discussions with the major business leaders in Arkansas who had helped fund his education reform effort—that he had to make the teachers accountable in some dramatic, clear way. And so, he imposed competency tests on the teachers. They hated it, but the public loved it. It helped Clinton politically so much to use the teachers as sort of a fake enemy. He set himself up in opposition to them in order to help himself politically and to get across this broader program, which he thought had a lot of merit. I don’t think he ever really wanted to use the teachers in that way, but they were just convenient for him. So, for about six years of his governorship, he and the teachers were at odds. Yet, when I was covering the [presidential] campaign in 1992 and went up to New Hampshire, there standing next to me was the former head of the teachers’ union, who used to denounce him all the time, campaigning for him. Clinton has a way of winning people over again.

In 1990, no one, including even his wife, knew until minutes before, and even maybe as he made the announcement, whether he was going to run again as governor for Arkansas. People in Arkansas who covered that race were trying to figure it out as well. It was stunning to me that one of Hillary’s friends called her and said, “Do you know what Bill’s going to do?” Here she is, his [wife and] main political adviser, and there was just enormous uncertainty about whether he would run again that year. Maybe that was a period when they weren’t as close as some other periods. He told the people when he ran for governor in 1990 that if he were elected he’d serve out four years. Someone asked him that question at a political forum, “Will you serve out your term if you’re elected?” In classic Clinton style, without even thinking, he said, “You bet.” Just like that, and then he had to live with those two words and break them.

[When he ran for president in 1992, he got 53 percent of the vote in Arkansas.] There’s a joke in Arkansas that they voted for him to get rid of him. That’s not it, obviously, but most of them think that Clinton is always asking for forgiveness of one sort or another. People in Arkansas are often willing to give it to him, and they knew all along that his goal was to be president. By the time he made that decision [to seek the White House], people in Arkansas knew him so well that those who were for him were for him no matter what; those who were against him hated his guts and didn’t care. There were no undecideds about Bill Clinton in Arkansas by that time; they’d known him for so long.

My book ends the day Clinton announced [his bid] for president.… This book is not about the 1992 campaign, and it’s not about Bill Clinton as president. I would argue that although the book ends the day he announced for president, everything that happened since is in the book, because his campaign, in essence, was his life coming back to him, and his presidency… [has] largely been recurring patterns of his career coming back to him.

There’s something in [my Bill Clinton biography] for everybody. There’s certainly a lot of material for Clinton’s enemies, as well as for his friends. I think they can find parts of his life where he was duplicitous, where he manipulated his way out of things and didn’t tell the truth about them later, and there are parts of the book where you can see that he’s a caring, compassionate, interesting person.

… The number-one question I get about Bill Clinton: What does this guy really believe the most? In a general way, I can say that I think he went into politics to do good and that his life and career have been that clash between idealism and ambition. If you’re looking at one issue, as a progressive coming out of the South, race relations always meant the most to him, was the burning issue of his childhood and youth, and that Vietnam really, in a sense, got in the way of what he wanted to do in terms of his political career and for civil rights; and then again, so did his ambition. So, there are two or three points in his career where you can see him making decisions on issues relating to civil rights that are controversial.

The hardest thing was to decide in my own mind what I felt about this guy. I’d go back and forth violently because there were chapters in his life where I liked him and chapters where I didn’t. So, I would beat myself up, saying, “Make up your mind; you’ve got to decide.” Then I realized—he is a dual person, and that I had it right.