GEORGE H. W. BUSH

41st President, 1989–1993

Historian: Jeffrey A. Engel

History and international relations professor Jeffrey Engel serves as the founding director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. He joined C-SPAN’s Q & A on August 29, 2018, to discuss his book, When the World Seemed New: George H. W. Bush and the End of the Cold War.

[If I had to describe George Herbert Walker Bush to someone who had never met him,] I would say he was a gentleman. I would say he’s a person who came up with traditional American values but also the values of being part of the elite. When we think about the term “noblesse oblige,” that really describes George Bush. He’s a person who was born well off, had the best education, had the best of training, and yet spent his entire life trying to work in public service to give more back. He really was just a gentleman of the kind that we really don’t see much anymore in American politics.

It started with his mother,… who constantly told him that your responsibility as a person to the manor born was to give back. She always stressed that the team was more important than the individual, which is very important for Bush, who was really into athletics throughout his life. He played baseball in college, and no matter how many times he would say, “Mom, here’s how I did,” she would say, “Yes but how did the team do?” I think it really infused in him a sense of the broader success being more important than the individual.

[Prescott Bush, his father, served in the US Senate from 1952 to 1963.] In George Bush’s life, it really demonstrated an example, if you will, of this kind of service that his mother had been describing her entire life,… the kind of service that his father exemplified, which was a service of compromise, service of negotiation. Prescott Bush was no firebrand. He was what we would call today a classic Eisenhower Republican. He was one of Dwight Eisenhower’s favorite golfing buddies. Eisenhower said, “I like to work with Bush. I like to play with Bush because he’s one of the only people that won’t let me win.” When you’re the president, you get a few mulligans.… And so, we really have extraordinarily little legislation that was authored by Prescott Bush but an extraordinary wealth of tales of him going behind the scenes, getting the two sides to come together in a way that’s very difficult even to conceive of today.

George Bush… spent a few years in the middle crucial years of his life in World War II in the South Pacific. Upon graduation [from high school], he and his friends, before they got drafted, all rushed to volunteer [for the military. This was] despite the fact that George Bush’s parents—and even the high school graduation speaker who was none other than Secretary of War Henry Stimson, a close family friend of the Bushes—encouraged Bush and those like him to go to college, spend a year or two getting a little bit more seasoning. The expectation was that these types of people would become officers, and a good officer would have a little bit more understanding of the world. Bush and his comrades had no interest in that. The United States had just been attacked a few months before, and they want to get into the fight before it was over, ironically not realizing quite how long it would go.

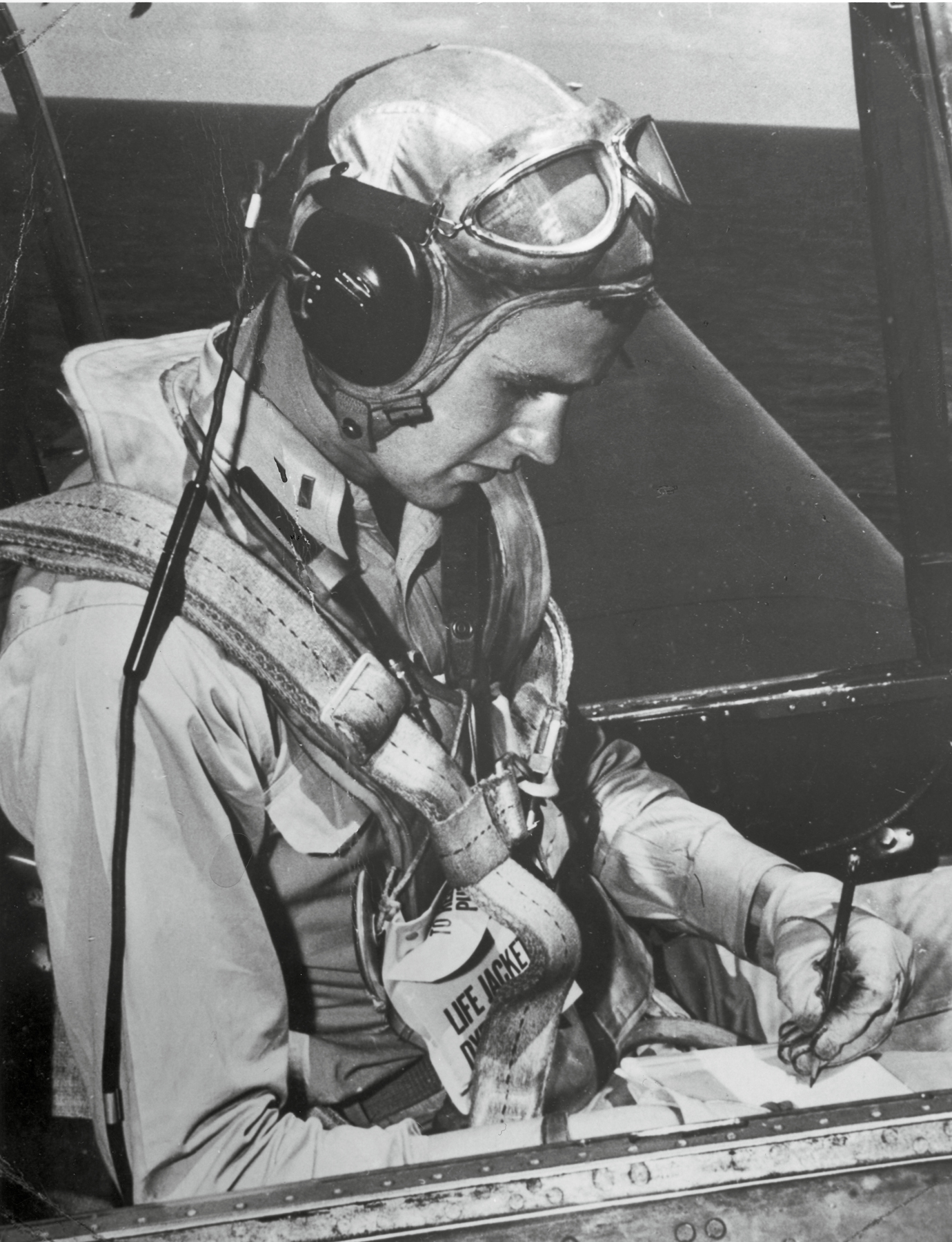

George Bush was eighteen, and here’s a good place where his family connections pay off. Having been unable to keep him from enlisting in the navy, his family was nonetheless able to get him a really coveted spot as a naval aviator. In fact, he ultimately becomes one of the youngest naval aviators in the entire Pacific theater,… remarkably young for having that sort of responsibility. He spent several years in training and then got sent off to fly torpedo bombers off an escort carrier. Also, as an officer he takes care of the men under his command, and it’s remarkable that at this point he’s only nineteen, twenty years old.

It was a searing lifetime event for him, in particular, the fact that he was shot down on September 2, 1944. He and his crew were on a bombing mission over the island of Chichijima. They were trying to take out a radio tower that they had attacked the day before unsuccessfully, and his plane was hit by enemy flak. Bush was able to hold the bomber aloft and keep it on track for the bombing run. Then, after dropping the bombs, he moved out to sea and told his crewmen, “Now, it’s time to bail out, time to go, hit the silk.” Then he himself jumped out and hit his head on the tail as it came by.

He parachuted down and realized as he was in the water all alone on the Pacific Ocean that there were no other parachutes. He realized at that moment that he was the only one of his crew that survived. That thought haunt[ed] him… [all of his life], I would say. He [told me] there was not a day that [went] by that he [didn’t] think about his two crewmembers under his command and why he was spared and they were not.… It’s largely one of those things that’s impossible to answer with full certainty. It’s pretty clear from the evidence that we have that they were most likely killed by the enemy shrapnel as it came in and that they were not able to get out.

He was in a small raft on the ocean, bobbing up and down, had taken in a tremendous amount of seawater, was vomiting. He writes home to his parents, subsequently, that he was crying profusely—the adrenaline having left his body at that point. And then he noticed something particularly bad, which is that his raft was beginning, with the current, to move towards the island. That was really not a good place for an American pilot to go.

We subsequently found out that other pilots who had been shot down on that island were not only killed by the Japanese, but there was some cannibalism that went on as well by the Japanese troops there. Bush, not knowing that but knowing capture is not a great thing for an American, paddles furiously the other direction, and ultimately an American submarine, the Finback, picks him up. He spends the next month underwater with the crew doing submarine missions until they could get back to base.

[He was in the military until] 1945. He had rotated back, had some more training, had fifty-eight combat missions. After he was shot down, he could have taken a break at that point, but he decided not to. Instead, [he went] right back to his unit to keep the fight up and not let his comrades down.

In 1945, he had just married Barbara Bush, and news comes out that the war is over. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought the war to a quicker end than people were expecting. And within three months, he was out of the service and onto his next step of life, which for him was Yale.… They gave [returning veterans] an accelerated program of studies, so he was able to graduate Yale in three years. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in economics and was part of the Skull and Bones Society, the single most prestigious [Yale] society.

He also was there with his wife and then, ultimately, with his small son, George. One of my favorite discoveries of the entire book is that Barbara Bush and George lived in an apartment complex that was next door to the official residence for the Yale president, who very kindly came over one day and asked her to stop putting out the laundry with [young] George’s diapers when he was having parties. So, it really gives a sense of how a person could go within six months from the terror of World War II into the bucolic life of New Haven in the ’40s.

… At the end of 1948, having just graduated from Yale, he had the opportunity to go to New York to work in his father’s investment house. And he instead decided: “I need to go and make my life on my own, make my own fortune, make my own way.” He hops in a Studebaker, a brand-new one, and drives across the country and winds up in Odessa, Texas. He had a friend of the family who had an oil company out there, and he began to work as a salesman for the oil company. Barbara and little George come a little bit after. I think this is a great moment for trying to understand who George Bush is on a profound level because, on the one hand, he’s a person who is able to take the leap of faith to say, I’m going to try something new and not rest on the laurels of my family to succeed. On the other hand, he goes out to Texas with a very large check from some investors back home, friends of his father’s, and he’s working for a family friend. He knows if Texas doesn’t work out, there’s always a job back in New York for him. So, it’s in a sense an adventure, but there’s a very large net beneath them, if you will.

[His national political career began in 1967 when he spent four years in the US House of Representatives.] The most important thing about that moment in his life is the time that he stood up to his constituents. He voted for the Fair Housing Act—something which was remarkably unpopular in his district back in Texas—even though he expected that this would perhaps ruin his political career. Ultimately, he went back to his district and explained that he had just come back from visiting American troops in Vietnam and couldn’t stomach the idea that an African American or Hispanic American… who would put their lives on the line in combat couldn’t come home and buy a house. He voted for that bill out of conscience, and it really demonstrated that at the end of the day, he did oftentimes see a higher purpose to service.

[In March of 1971, he became the UN ambassador for twenty-two months.] They were, perhaps, his happiest years of his life. He found that he really loved diplomacy. He had run for the US Senate from Texas. He had given up his very safe House seat in order to do so. He was expecting to run against a relatively liberal candidate on the Democratic side. Instead, he found himself running against Lloyd Bentsen, who one can safely say was more conservative than George H. W. Bush.… He lost that election. But he had in the back of his pocket a promise from President Richard Nixon that if he did this run for Senate, and if it didn’t work out, the next administration would take care of him.… They found a… position for him at the United Nations, at which point it was pointed out that George Bush had zero diplomatic experience, and his international experience had largely come during World War II. Bush very wisely turned that into a virtue. He explained to the White House staff under Nixon that since he didn’t know anything, he would do exactly what Henry Kissinger said. That’s exactly what Henry Kissinger, the secretary of state, wanted to hear.

[On January 19, 1973, he began as the chair of the Republican National Committee for twenty-one months, in the middle of the Watergate scandal.] He did it because the president asked.… The time at the RNC was arguably the worst time, politically, in his professional life.…

It became difficult, of course, [because] Bush had the unenviable job of being forced to go out on the stump every day and defend the president, a president who he increasingly over time came to believe, and then know, had been lying to him. So, like other Republicans at that time, the moment they realized not so much that they had been lied to, but they had been made to lie for Nixon, that was a moment that he and others encouraged Nixon’s resignation.

[On September 26, 1974, he went to China as the US liaison for fourteen months.] Gerald Ford sends him there, the president who comes after Nixon, essentially as a reward for the good service he had done for the Republican Party.… He thought that going to China would be an adventure, much like when he first went to Texas. It would be something that was completely brand new, something completely foreign, and something completely exotic and exciting. If there’s one conversation in his life I wish I had been a fly on the wall for, it’s when he came back and informed Barbara that they were going to [be posted in] China.…

[Next, he served as the director of the Central Intelligence Agency for 357 days.] That came about as a long-term vestige of the difficulties of Watergate and Vietnam. The CIA was under tremendous pressure from congressional investigations at this point, and Gerald Ford decided to shake things up and move people around within his cabinet. He called Bush home in order to be CIA director. This was [an assignment—chief spy—that] Bush thought was going to kill his political career.

… When President Carter wins in 1976, Bush asked him if he could stay on at the CIA, but Carter wanted his own CIA director. So, Bush spends the next three years essentially prepping for his run in 1980. He goes back to Houston but really spends most of his time on the road meeting people in all the different states. Nineteen eighty is when he finally ran against Ronald Reagan. It was ultimately the best first challenge against Reagan in the sense that Bush managed to win the Iowa caucuses. Ronald Reagan at that point had assumed he was going to steamroll to the convention… and really didn’t put too much time into Iowa. Bush made a point of visiting every single county in Iowa and shaking hands there. He wins the Iowa caucus, but frankly it’s downhill from there once Reagan gets his full attention in the campaign.…

Bush winds up being the last man standing against Ronald Reagan and gives us some of our most important historical phrases and criticisms about Ronald Reagan. Bush, for example, is the one who comes up on the campaign trail with the term “voodoo economics” to describe trickle-down economics, or supply-side economics as Reagan would have preferred. We still use the term “voodoo economics” today, and we forget that it ultimately was Reagan’s vice president who used that as a criticism against him when they were both going for the top job.

The 1980 convention was a weird one, historically, because there began to be talk that perhaps Ronald Reagan would choose Gerald Ford to come back and be his vice president. They would essentially be co-presidents, and these negotiations got very close before both sides realized this would never work, that somebody had to be in charge ultimately. Reagan then had to turn and find someone to be vice president, and the logical choice was the one who had been last man standing in the campaign, George Bush. It’s a testament to both men, both their sense of opportunism and also their basic characters, that they were willing to look past the criticisms [during] their primary campaigns to work together over the next eight years.

[George Bush ran to succeed Ronald Reagan in 1988.]… One of the remarkable things about the Republican primary in 1987 and ’88 is just how far most of the candidates on that field are trying to run away from the legacy of Reagan. We think of Reagan through the lens of history as someone who was remarkably popular. But at the end, he was personally popular, but his policies were not, especially his policies vis-à-vis the Cold War, and he still had the taint of Iran-Contra, as well. Most of the candidates were trying to criticize Reagan’s legacy. Given his experience in 1980, had Bush not been a member of the administration, he would have been first in line to criticize Reagan in 1988.

Bush has a remarkable ability throughout his career, especially when he’d gotten to national-level politics, of being able to surround himself with people who would do the dirty work that needs to get done for an election, as he saw it. Lee Atwater, Roger Ailes, people who would play politics… as tough as possible—OK, I’ll use the word “dirty.” Bush would always have a sense of remove that he could say, “I did not order that,” “I did not know about that plan,” “I didn’t know about Willie Horton,” for example, despite the fact that his campaign clearly knew that the Willie Horton ad was going to run; Willie Horton being the famous racially charged advertisement that the Bush campaign ran in 1988. There was always somebody around him who could be the hitman. Ailes and people like Atwater played that role for him.

… I’ve seen documentation from people like Lee Atwater, in particular, who said, “We made a point of not discussing such things.” This is not to alleviate Bush of any complicity or guilt in these situations. He was in charge. Ultimately, he is responsible for what happens with his campaign. But it does give a sense of the tone that he wants to set, that he told his people, “We’re going to go for the win; we’re going to do whatever it takes to win. We’re going to play dirty, and in many ways, both play the race card and try to emasculate Michael Dukakis,” their campaign opponent. He wanted those things done, but he wanted somebody else to do it. [In 1988, Bush trounced Michael Dukakis, 53 percent to 45 percent, winning 40 states and 426 Electoral College votes.]

… No president has ever been as prolific as a letter writer, as a note writer, as a person who maintained personal contacts across his entire life. I understood that at its height, the Bush Christmas card list was over twenty-five thousand people. Once you became a friend of George Bush’s, you remained that way. He really believed that the personal touch was built over time. One of the most amazing things that we were able to get declassified and pull out of the Bush library to write this new history was all of the transcripts of phone calls that President Bush had with foreign leaders around the world. Every time he picked up the phone to talk to a foreign leader, we have that transcript. What’s amazing is how little talking he did. He oftentimes would call people up, the [prime minister] of Australia or the president of Zimbabwe, and say, “What’s going on in your world? What do you think about the situation?” And, he’d just listen.

My book is fundamentally about the end of the Cold War. It’s silly to think that any one person is responsible for ending the Cold War, but if you had to choose somebody who was more responsible than anyone else, it would be Mikhail Gorbachev. He is really the central catalyst that gets the entire democratic explosion started. His desire to reform the Soviet Union—not to eradicate it; he was a true Soviet believer—but [he wanted] to reform and revitalize it, not set in motion the democratic revolutions that brought down his country’s empire.

Bush had a tremendous responsibility for making sure that Gorbachev’s reforms continued to go peacefully. Bush walked a tightrope throughout his entire first year in his administration knowing that if he pushed too hard on the Soviets, that could cause perhaps a counterrevolution, a conservative revolution against Gorbachev and the other democratic revolutions in Eastern Europe. If he was too easy on Gorbachev, well, then perhaps that, too, could cause a counterrevolution. Then Gorbachev’s opponents, and he had many, might say, “You’re clearly too close to the Americans; you must not have our interests at heart.” That’s the macro influence that Bush had on the immediate evening of the fall of the wall.

[The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989,] was a surprise. It was actually a mistake. East German spokesmen read the wrong memo on television, giving the wrong information, giving people the impression that they had the right to cross the border. When tens of thousands of people saw that on TV and rushed to the gates, the guards there made the wise choice that they should open them up rather than mow the crowd down, rather than having, [as China did] a Tiananmen Square[-type massacre]. No one [inside the Bush administration] had any idea. It wasn’t supposed to happen. It was an absolute mistake. I have a wonderful memo from about two days before the wall fell from Bush’s National Security Council that says, and I’m paraphrasing, “We should think about the fact that there might be a change in the border status. We should start planning how we might want to put together a committee to start thinking about how we should react.” That’s a typical bureaucratic start to something that you expect is not going to happen for six months, or a year, or maybe never. Most of the people who saw the Berlin Wall fall on November 9, 1989, had the same reaction, which was this was something we never thought we’d see in our lifetimes.… And then, suddenly it happened, to everyone’s surprise.

[The 1991 Gulf War was another defining time in Bush’s presidency.] The most important things about Iraq are threefold. The first is just how much Iraq was—for Bush and those around him—not about the Middle East, but about the end of the Cold War. They understood the Berlin Wall had fallen. The Soviet Union is transforming rapidly. They understood that the world had changed, and however the international community chose to meet the threat of violence, the first time after that change would set the pattern for decades to come. Iraq mattered, but ultimately what mattered more was the post–Cold War sentiment that they were trying to create and precedent that they were trying to create.

The second thing that was really fascinating about the Gulf War was that Bush was fully prepared to go to war in January of 1991 with five hundred thousand American troops in the region, and war planes, and ready to go, even if Congress on the eve of that battle had voted against giving him authorization. It was a remarkably close vote; only a few votes tipped the balance. Bush wrote numerous times in his diary, and I have this confirmed by many people within the upper levels of his administration, that even if he lost the vote, he was still going to use his authority to send American troops in the combat. He recognized this would be a clearly impeachable offense, but he had an interesting rationale about it. First of all, he thought it was the right thing to do. He thought Saddam Hussein had to be taken out at that point. But secondly, he thought, “We’re going to win this war, and frankly we’re going to win this war quickly. Presidents who win wars quickly are very popular, and I would like to see Congress try to impeach me when I have a 90 percent approval rating.” So, he thought that before impeachment hearings could possibly get moving, the war would have already been over by several weeks. And, he was willing to take that political risk.

[The third point about the war was the decision not to remove Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in 1991.] Every member of the Bush administration will give you the same answer, which is also borne out by the documentary evidence.… No one in 1991 in the Bush administration, including [then Defense Secretary] Dick Cheney, thought it was a good idea to go on to Baghdad.

The reasons they gave are really haunting for us today: they suggested that the Iraqis would treat us like a foreign occupying force; they suggested that it would create ethnic and religious tension that would potentially lead to civil war; they thought it would put tremendous strain on the Israeli-Palestinian issue, which is the center of so much of Middle East politics. And frankly, Bush recognized that if you own Iraq, metaphorically speaking, you are responsible for it. That was a responsibility that the United States either shouldn’t take, or perhaps wouldn’t even be able to be successful at. And, we didn’t need to because our expectation is that… Saddam Hussein is most likely going to die from a coup from his own officers. That was really the most likely bet at that point [which proved wrong].

I had the great privilege of going down [to Texas] a couple of times and reading chapters of the [finished] book to him and Mrs. Bush before [they] passed.… It was a remarkable opportunity that very few historians ever get, to read their work to their subject.

President Bush [was] remarkably supportive in a way that should be an example to other people who formerly held power. He always stated and always understood that the job of people who make history and the job of people who write history are fundamentally different and have to be separate; that his job was to answer every question as truthfully as he could, and my job was to assess things as truthfully as I could.

I found many things, which I explain in my book, where I think President Bush was misinformed, where he had mistakes in judgment. Overwhelmingly, I come away extraordinarily impressed by the job he did, especially as a diplomat. Even an All-Star hitter strikes out from time to time.