CHAPTER 2

LAW ENFORCEMENT

CATCHING KILLERS IS BUILT ON OLD-FASHIONED DETECTIVE WORK, BUT TODAY, OFFICERS ALSO HAVE GADGETS WORTHY OF JAMES BOND TO HELP THEM TRACK DOWN THE BAD GUYS.

There were more than 3.7 million arrests for nonviolent crime in the U.S. in 2009.

THE DETECTIVE’S PLAYBOOK

HOW DO YOU SOLVE A CRIME? PHYSICAL EVIDENCE, OLD-FASHIONED INTERVIEWS, AND COOPERATIVE WITNESSES.

Chicago police investigate the scene of a shooting.

There were 506 murders in Chicago in 2012, the most of any metropolis in the United States. The same year, the Windy City recorded about seven murders per 100,000, more than the national average of five per 100,000. Local police also solved a dismal 25 percent of homicides, the department’s worst performance in more than two decades and well below the national clearance rate of 60 percent.

Faced with these statistics, the Chicago Police Department decided to try something new in 2013. It added 70 new detectives to the force and put them to work on homicide cases in teams of eight or 10 instead of one or two. The restructuring allowed for ongoing investigations even during individual vacations or absences. With expanded staff and new avenues for teamwork, the department improved its clearance rate by 5 percent in a single year.

There were unexpected consequences as well. Ordinary citizens, noting how the police were committing more resources to their neighborhoods, became more willing to step forward and identify perpetrators, the department said. Cooperation seemed to increase from the moment a homicide was suspected.

Group Effort

Such collaboration is key to the success of any law enforcement team. It starts the moment personnel arrive at the murder site, as crews secure the crime scene, collect physical evidence, take meticulous photographs, and send evidence to a crime lab for analysis. While the crime scene investigators are doing their jobs, detectives are identifying and interviewing any witnesses that might have valuable information to contribute about what happened. These are the steps every department relies on for leads to solve crimes.

Friends and Family

If no obvious suspect emerges quickly, police begin interviewing people within the victim’s circle. All but about 20 percent of murder victims are killed by someone they know—an acquaintance, spouse, romantic partner, or family member—so investigators start there. If these interviews aren’t fruitful, authorities may solicit tips from the public and follow up on them selectively.

Once a suspect is arrested, the easiest and fastest way to close a case is by obtaining a confession. In fact, crime experts estimate that 80 percent of cases end with a suspect admitting he or she did it. At that point, law enforcement usually considers the case cleared, and it’s on to the next one.

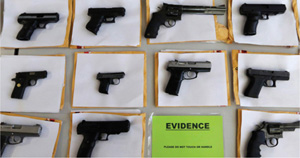

A display of some of the 3,400 illegal firearms seized by the Chicago police in the first six months of 2014

WHO KNEW?

The violent crime rate in the U.S. peaked in 1993 and has been falling ever since, according to the FBI.

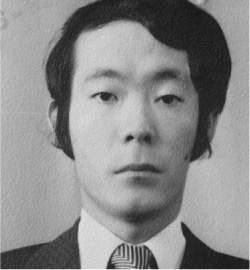

A deathbed confession eventually led to the arrest of Jack Daniel McCullough, formerly known as John Tessier.

A VERY COLD CASE CLEARED … MAYBE

After 55 years, police were able to avenge a murdered second-grader. But did they get the right killer?

The oldest known solved cold case in the United States ended thanks to a deathbed confession. In 1993, as an Illinois woman named Eileen Tessier lay gravely ill in a hospital, she told her grown daughter, Janet, “John did it.” Tessier was referring to her son, John Tessier, who she was claiming was behind the kidnapping and murder of seven-year-old Maria Ridulph in 1957.

For the next 15 years, Janet tried unsuccessfully to get authorities to reopen the Ridulph case. But it wasn’t until she sent an email to the Illinois State Police in 2008 that she got results. The tip led to the arrest of John, who at the time was living in Seattle under the name Jack Daniel McCullough. In 2012, McCullough, then 73, was convicted of kidnapping and murder. He is serving a life sentence, but has maintained his innocence and appealed the conviction.

CRIME SCENE INVESTIGATION

FINGERPRINTS AND FIBER ANALYSIS CAN MAKE A COURT CASE. BUT SUCH FORENSIC SCIENCE CAN BE LESS RELIABLE THAN YOU THINK.

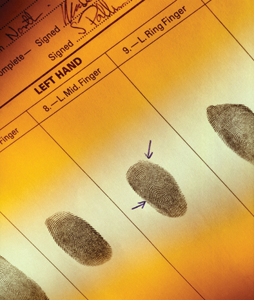

Fingerprints are records of the friction ridges found on the skin. Traditional fingerprinting relies on ink and paper to record the individual whorls and loops.

Crime fighters have used lab tests as evidence for hundreds of years. A postmortem exam to detect arsenic poisoning was first developed in 18th-century Sweden. Scotland Yard began studying the characteristics of bullets in the early 19th century. Fingerprinting came into vogue in the late 1800s in Europe, and by the early 1900s was imported to the United States by the New York City Police Department. These days, forensic science is widely relied on—but it is hardly foolproof.

In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences even published a study, “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward,” that revealed which crime-lab techniques are scientifically sound and which ones aren’t. Surprisingly, the “unreliable” category included a number of long-used crime-solving techniques, from hair analysis to lie-detector tests.

Inexact Science

Shoe prints, for example, are a favorite in detective stories, but they are not considered scientifically rigorous evidence. There is no official number of criteria a shoe print must meet before it is determined to be a match to one specific shoe, and drawing conclusions based on such prints can be risky. Similarly, bite marks on a victim’s body can be unreliable; the same goes for fingerprints. The alignment of a person’s teeth can shift over time, for example, and police aren’t always able to obtain a full fingerprint from a crime scene. Sometimes even the best fingerprint analysts make mistakes.

Then there’s hair analysis, identifying a strand of hair or fiber based on characteristics such as texture, diameter, and distribution of pigment. Even highly competent analysts can have trouble distinguishing between human and animal hair, let alone reliably connecting the strand to a particular human.

The one forensic test that is quite reliable in proving a suspect’s guilt or innocence is DNA. Developed in the early 1980s by a British geneticist, this procedure has been refined in the ensuing decades and has even been used to exonerate a number of innocent people who had been convicted on the basis of other forensic evidence.

WHO KNEW?

Despite the conventional wisdom, it has so far never been proven that everyone’s fingerprints are unique.

NO LIE

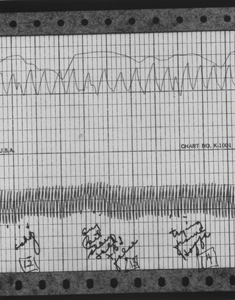

The controversial “lie-detector test” is relatively easy to skew in your favor.

Chances are, you’ll never have to take a polygraph or lie-detector test. It is illegal to force anybody—even someone under arrest—to submit to one, and it is generally forbidden for an employer to require one. In many states, even voluntary polygraphs are inadmissible in court.

Should you ever be subjected to one, these counter-strategies are said to be fairly effective.

1. Recognize the “control questions.” Polygraph tests work by measuring your physical responses when you lie. To get a baseline sense of how much you sweat and how dramatically your pulse and breathing increase, the interviewer first asks questions you will answer truthfully, such as your name and whether you are wearing a gray suit.

He then asks a few questions that you might be inclined to fib about such as, “Have you ever stolen anything?” or “Have you ever been fired from a job?” These questions are broad on purpose—you’ve probably stolen something in your life, even if it’s just a paper clip. When you say no, you’ve never stolen anything, the machine registers a little jump in your vital signs and your physical parameters are established.

2. Punch up your physical symptoms. Before you answer these kinds of control questions, think of something scary, try to solve a complex math problem in your head, or bite down on your tongue so that your physical response is exaggerated.

3. Calm yourself down. During the relevant questions—the ones you want to seem to be answering truthfully, even if you aren’t—keep your breathing controlled and think of something nice.

Lie-detector test given to Teamster Ed Partin after he claimed that union leader Jimmy Hoffa had threatened to kill Robert F. Kennedy.

Casey Anthony before the start of her sentencing hearing in Orlando, Florida.

ARMCHAIR EXPERTS

To the dismay of prosecutors, juries who watch popular television shows such as CSI: Crime Scene Investigation want iron-clad proof of guilt.

Television dramas in which the leads rely on forensic evidence to solve crimes are wildly popular, endlessly fascinating, and—according to some prosecutors—seriously interfering with their ability to convict bad guys. Thanks to a phenomenon they call “the CSI effect,” lawyers say more juries now demand absolute proof to render a guilty verdict. They want the kind of evidence they see on TV: high-tech and 100 percent accurate. The trouble is, it’s not always possible to obtain definitive forensic evidence, and some of the techniques shown on these shows don’t even exist.

Some believe the CSI effect played a role in the 2011 acquittal of Casey Anthony, the Florida mother accused of killing her two-year-old daughter, Caylee. Media outlets observed that the prosecution presented significant circumstantial evidence but was unable to provide the kind of conclusive forensics seen on CSI. The jury found Anthony not guilty.

INSPECTORS WITH GADGETS

CUTTING-EDGE TECHNOLOGY IS HELPING LAW ENFORCEMENT PREVENT CRIME AND CATCH CRIMINALS.

Monitors from security cameras at the Lower Manhattan Security Initiative in New York City, 2013

In July 2013, after a number of auto burglaries were reported in a parking garage in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the local police set up a sting operation. They parked a “bait car” in the garage, with unlocked doors and a purse inside. When the thief showed up, opened the car door, and began to search through the purse, he got a surprise: The bag had been rigged to spray him with SmartWater CSI—a long-lasting high-tech liquid (not to be confused with the similarly named brand of bottled water) that goes on clear but is visible under a special light. When detectives caught up with the 21-year-old suspect several hours later, the proof of his misdeed was all over his face.

Crime-fighting tools are getting positively James Bond—like; they include a wide array of gadgets and software to help nab bad guys and even stop crime before it starts. In Memphis, Tennessee, for example, a database called Blue CRUSH, which identifies crime patterns by neighborhood, helped reduce murders and robberies by more than a third and car thefts by more than half in the six years following its 2006 inception.

Electronic Eyes

Some police departments are enlisting the public in high-tech crime prevention. In Akron, Ohio, police ask local businesses and homeowners with security cameras to register with a program called DIVRT. The DIVRT software can connect to participating surveillance cameras and grab footage of holdups or other crimes captured on a particular camera. Then cops can quickly broadcast the footage on social media and send it to local news outlets, netting them valuable tips from eyewitnesses and the general public.

In some cases, technology can be better than humans. In East Chicago, Indiana, police use a device called ShotSpotter, which can detect the sound of gunfire via special sensors posted around the city. The technology pinpoints the exact location of a shooting within about a minute, allowing police to rush to the scene more quickly than they could by relying on phoned-in tips.

These futuristic methods and gadgets are not mistake-proof, and could lead criminals to become more tech-savvy themselves. But law enforcement is working to stay a step ahead of them.

A special flashlight reveals yellow markings to show where SmartWater was sprayed.

WHO KNEW?

The New York Police Department uses facial recognition technology to identify suspects caught on surveillance cameras and match them to a database of mug-shots—or photos on Instagram and Facebook.

THE FUTURE IS NOW

Some simple technological advances—mostly involving databases—have had a profound impact on law enforcement.

NAME: CODIS (Combined DNA Index System)

WHAT IT IS: This national database records suspects’ DNA evidence gathered from crime scenes.

HOW IT’S USED: To match the perpetrator of one crime (such as a sexual assault) to other crimes committed elsewhere.

WHERE IT’S HEADED: Improvements in CODIS will also help identify missing persons using DNA.

NAME: Blue CRUSH (Crime Reduction Utilizing Statistical History)

WHAT IT IS: The Memphis Police Department, in Tennessee, analyzes data on every crime reported in the city.

HOW IT’S USED: When patterns emerge in certain parts of town, cops head there to discourage criminal activity.

WHERE IT’S HEADED: The MPD has added a community outreach program to help find longer-term anticrime solutions in troubled neighborhoods.

NAME: ALPR (Automatic License Plate Reader)

WHAT IT IS: Police in most cities use scanners to record license plate numbers and match them to a database.

HOW IT’S USED: Cops can identify stolen cars, track wanted felons, and identify vehicles in AMBER alerts in child abduction cases.

WHERE IT’S HEADED: Opponents say the technology violates privacy: Anyone’s plate can be scanned, even if they’re not suspected of anything.

A street surveillance camera on a light pole in Chicago

WE’RE WATCHING YOU

Is the huge increase in the number of private and public surveillance cameras a boon to crime-fighters, or an invasion of your privacy?

If it seems as if there are video cameras everywhere, it’s because there are. In the decade after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, American businesses, governments, and private citizens bought an estimated 30 million video cameras in an effort to boost security. In Chicago alone, there are an estimated 24,000 cameras posted around the city.

In numerous instances nationwide, recordings from security cameras have helped prevent and solve crimes, including acts of terrorism. After the Boston Marathon attacks in April 2013, footage from the area’s hundreds of private and public cameras helped the FBI identify alleged bombers Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev. But at what price? Critics of the security-camera boom say it’s an invasion of citizens’ privacy to constantly monitor us wherever we go. That debate is likely to continue, as is the escalation of video security measures in urban centers and high-risk areas.

TO CATCH A KILLER

A SPECIAL FBI DATABASE HELPS LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES ACROSS THE NATION CONNECT THE DOTS IN UNSOLVED VIOLENT CRIMES.

Rafael Resendez-Ramirez, who is suspected of killing at least eight people, is driven to jail in Houston, Texas, after surrendering to officials, 1999.

A police officer looks at a photo of Rafael Resendez-Ramirez, wanted by the FBI.

Catching killers has always revolved around quality detective work, from composing detailed crime scene reports to scrutinizing autopsy results. Today, it may also depend on a search of a special FBI database, the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program (ViCAP), which collects information from police departments around the country about homicides, sexual assaults, and missing persons.

Finding Patterns

Created in 1985 and headquartered in Quantico, Virginia, the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program is a unit of the FBI that assimilates and analyzes information about serial crimes and seeks to identify the perpetrators. ViCAP agents look for patterns that might reveal the “signature” of a criminal, drawing parallels among widespread or seemingly disparate cases. The database they use includes contributions from more than 4,000 law enforcement agencies covering as many as 90,000 cases. In 2008, this data was made available for the first time to local law enforcement agencies around the country via a secure internet link.

How It Works

Here is a hypothetical example that illustrates how ViCAP can help find a suspect.

A young jogger in Texas disappears while out on a run in her local park. Her body, showing signs of sexual assault, is found a week later, and it is determined that she has died from a blow to the head. Investigators clear all of the woman’s known associates, then turn to ViCAP.

Texas police discover in the database information about another jogger who was sexually assaulted five months earlier in Alabama. They contact authorities in Alabama to compare notes. Meanwhile, a ViCAP analyst in Virginia is reviewing a similar case involving a Georgia jogger. That victim, who escaped, has described her attacker as a tall, thin, redheaded man with glasses, wielding a lead pipe.

While researching the Georgia incident, the ViCAP analyst finds the Texas and Alabama cases in the database. The analyst and the Texas, Alabama, and Georgia investigators pool what they know about the cases, and a suspect is identified and arrested: He is a high school track coach who had visited Texas, Alabama, and Georgia for track meets around the times of the corresponding murders. His DNA is tested and found to match that retrieved from the various victims.

ViCAP’s Critics

The FBI does not release information on how many criminals are apprehended because of ViCAP, so it is difficult to judge its effectiveness. Critics point to various shortcomings, such as the wording of questions on the ViCAP form. They also complain that the links between the various crimes in the database can be tenuous. Criminologist Jack Levin worries that the data is incomplete since most states do not require their police to register reports with ViCAP. Only a third of the nation’s homicide cases are reported to ViCAP, says Levin, who adds that serial killers don’t always stick to a pattern. “Their methods often change from victim to victim,” which makes their crimes more difficult to link, Levin told the Oakland Press.

Nevertheless, ViCAP serves a valuable purpose for law enforcement, says former detective Robert Keppel. “What these critics don’t realize is that ViCAP was not intended to provide any sort of expert linkage or sophisticated statistical analysis. Its main function is that of a pointer system to help detectives find similar cases so they can communicate with each other one-on-one about the possibility that cases are linked.”

WHO KNEW?

Rafael Resendez-Ramirez, known as the “Railroad Killer,” was caught after ViCAP tied him to murders by searching for cases of vagrants murdered in railroad yards.

WHEN SERIAL KILLERS SLIP UP

Serial killers sometimes get caught because of their own careless mistakes.

• Ted Bundy, one of the most notorious serial killers in American history, was caught after a cop pulled him over. In the backseat, the officer found burglary tools in plain sight.

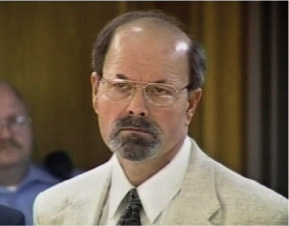

• Dennis Rader, the self-annointed “BTK Killer” (Bind, Torture, Kill), was arrested in 2005 after he sent a taunting message to police on a floppy disk. Forensic analysis linked the disk to Rader’s church, where it was being used by a guy named “Dennis.” He pleaded guilty to ten murders and is serving a life sentence.

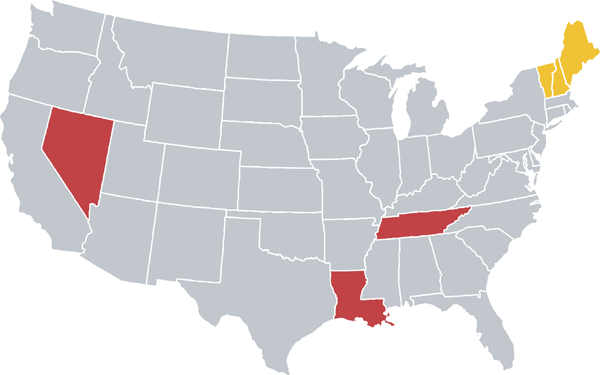

According to the U.S. government statistics, there were 440 violent crimes for every 100,000 people in the United States in 2009, the most recent year such national data is available. But violent crimes per capita vary greatly from state to state and there is not always a correlation between a state’s violent crime rate and the size of local law enforcement. The three states with the lowest violent crime rates have among the smallest police forces per capita in the country. New Hampshire, with the lowest murder rate, hasn’t had the death penalty for more than 130 years.

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2012; census.gov. FBI Crime Clock Statistics; fbi.gov.

THE MOST DANGEROUS STATES

NEVADA

654.7 violent crimes per 100,000 people—highest in the country

13th in number of police officers

LOUISIANA

628.4 violent crimes per 100,000 people

11.2 murders per 100,000 people

542.8 police officers per 100,000 residents

Has 8th highest violent crime rate in the U.S.

TENNESSEE

607.7 violent crimes for every 100,000 people

Ranks 22nd of 50 in incarceration rates

Spends an average of $11.67 billion annually to combat violent crime

The crime rate has gotten steadily worse each year since 1991.

THE SAFEST STATES

MAINE

120.2 violent crimes for every 100,000 people

Lowest incarceration rate—148 per 100,000 people

Smallest police force of all states

VERMONT

135.1 violent crimes per 100,000 people

1.1 murders per 100,000 people— the second lowest in the United States

4th lowest in number of police officers

Spends an average of $447 million to combat violent crime

NEW HAMPSHIRE

169.5 violent crimes per 100,000 people

1 murder per 100,000 people—the lowest in the United States

WHAT’S THE MOST COMMON WEAPON USED IN ROBBERIES?

In 2009, more than a third of robberies were committed without a weapon, according to the U.S. Census.

gun 131,000

physical intimidation 126,000

knife 24,000

other weapon 27,000

WHEN DO MOST BURGLARIES OCCUR?

The common assumption is that most burglaries occur at night, but government statistics show otherwise.

daytime: 910,000

nighttime: 625,000

ADMITTING IT

A SURPRISING NUMBER OF PEOPLE CONFESS TO HORRIBLE CRIMES THEY DID NOT COMMIT.

On March 30, 1934, a white planter, Raymond Stuart, was brutally murdered in Kempner, Mississippi. The three suspects, Ed Brown, Arthur Ellington, and Henry Shields, were black tenant farmers who were initially denied an attorney and were tortured by police until they confessed. Though their statements were the only evidence linking the sharecroppers to the crime, they were convicted and sentenced to be hanged within a week. A series of appeals took the case, Brown v. Mississippi, all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1936, the justices unanimously reversed the convictions and outlawed coerced confessions.

It is not unusual for plaintiffs to admit to crimes they have not committed. According to the Innocence Project, roughly 27 percent of those who have been convicted of a crime and later exonerated by DNA evidence confessed to something they didn’t actually do.

Forced to Lie

Psychologists divide false confessions into three categories.

COERCED-COMPLIANT CONFESSIONS. These are instances where the innocent person is compelled to confess by outside pressures, such as police interrogation.

The coerced-compliant confession is the most common type of false admission, though reasons for cooperation vary. Sometimes, the accused doesn’t have legal representation. Subjected to rigorous questioning, discomfort, or psychological abuse for hours without a break, he may confess just to put an end to the agony, or out of stress or confusion.

This confessor might be falling for a bluff—a claim that someone has implicated him in the crime, that evidence has been found in his home, or that other incriminating facts have come to light. Similarly, this kind of suspect might react to interrogators who threaten a harsh sentence; or might confess to win leniency for another, more serious crime that they actually have committed.

The inexperienced, the young, the mentally disabled, and the mentally ill may confess simply in an effort to live up to the expectations of police officers and other authority figures. Similarly, adults who are ill-informed, poorly educated, or even intoxicated often can be easily manipulated into making false, self-implicating statements that they don’t fully understand.

VOLUNTARY CONFESSIONS. Here, the suspect might be motivated by allegiance to a loved one or an organization, or might have been paid to take the blame.

The voluntary confessor doesn’t need to be persuaded. Typically, he cooperates enthusiastically, without pressure from law enforcement. Voluntary confessions are sometimes meant to draw attention away from an actual criminal—perhaps to protect a guilty loved one. Other voluntary confessions have unconscious psychological roots: On rare occasions, an innocent person confesses falsely in an attempt to atone for some other perceived or real wrongdoing.

Some false confessors pretend to have committed a crime, often a high-profile, unsolved murder, in a bid for notoriety. Forensic psychologists attribute this behavior to a pathological craving for attention so strong that it transcends fear of punishment. These impostors are usually quickly unmasked.

COERCED-INTERNALIZED CONFESSIONS. In such cases, an innocent person persuades himself that he is guilty of the crime, sometimes even falsely “remembering” it. Confessions of this type are relatively rare and are extremely difficult to disprove in court.

Interrogation tactics such as intimidation can produce false confessions.

WHO KNEW?

In the early 1980s, Henry Lee Lucas was convicted of 11 murders, but he officially confessed to 600 more.

THE GREAT LONDON SCAPEGOAT

Watchmaker Robert Hubert claimed to have started this notorious and devastating fire. But did he really do it?

The Great Fire of London in 1666 destroyed about 80 percent of the city, left 100,000 homeless, and is thought to have killed thousands.

Robert Hubert, a mentally ill French watchmaker, came forward to take responsibility for the crime. Claiming to be an agent of the Pope, Hubert said he set the conflagration by throwing a bomb through a bakery window. Predominantly Protestant London was quick to turn the Catholic foreigner into a scapegoat, even though it became clear during the trial that his confession was suspect. It was established that he had never been near the bakery; that the bakery had no windows; and that he was physically incapable of throwing a bomb. Hubert hadn’t even arrived in England until two days after the fire started.

But the Frenchman stuck to his story, and an eager jury found him guilty. After he was hanged, the Earl of Clarendon, Lord Chancellor of England, who was responsible for the court system, noted that “neither the judges, nor any present at the trial did believe him guilty; but that he was a poor distracted wretch, weary of his life, and chose to part with it.”

Fleeing the Great Fire of London, illustration, published in 1815

MASS CONFESSIONS

In some cases, the number of people who confess only adds to the horror of the incident.

• A Two-Year Search More than 200 pretenders claimed responsibility for the 1932 kidnapping of the toddler son of world-famous aviator Charles Lindbergh. The police spent two years following every lead, no matter how bizarre. Ultimately, German-born carpenter Bruno Richard Hauptmann was convicted and executed.

The son of aviator Charles Lindberg

• The Black Dahlia One of the most publicized murders of the 20th century was the 1947 slaying and dismemberment of 22-year-old Elizabeth Short, a waitress in Los Angeles whom the newspapers dubbed the “Black Dahlia.” Following lurid and largely inaccurate press coverage, about 60 people confessed. Though the LAPD considered about 25 of them viable suspects, none proved to be the murderer. The case remains unsolved.

Police still get tips about the killing of Elizabeth Short.

AND JUSTICE FOR ALL?

WHEN A COUSIN OF THE KENNEDYS IN JAIL FOR MURDER WAS FREED FOR A POSSIBLE RETRIAL, SOME CRITICS CALLED FOUL.

Advocates for social justice have long complained that America has a two-tiered legal system: one for the elite who can afford the best defense lawyers money can buy, and another for everyone else. In this view, criminals from powerful or well-to-do backgrounds lead such privileged lives that they feel the rules don’t apply to them. In addition to acting as if they were born with a get-out-of-jail-free card, these lawbreakers are often treated that way.

A Question of Privilege

Michael Skakel today is the middle-aged nephew of Ethel Skakel Kennedy and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy. Growing up in the wealthy town of Greenwich, Connecticut, Skakel led a cosseted life, but struggled in the shadow of his abusive and alcoholic father, according to media accounts. He allegedly began using alcohol and drugs as a teen and soon landed in serious trouble.

In 1975, when Skakel was 15 years old, his next-door neighbor and friend Martha Moxley, also 15, was found dead. An autopsy indicated that Moxley had been bludgeoned with a golf club that was traced to the Skakel home.

Michael Skakel allegedly confessed to two friends that he was the killer and bragged, “I’m going to get away with murder. I’m a Kennedy.” At different times, the teen was investigated as a suspect, and so was his brother Thomas, the last person to be seen with Moxley. But neither young man was arrested, and many complained that the Skakels, with their link to America’s most famous family, had been afforded special treatment.

A New Investigation

A number of books published on the crime as well as media attention prompted a new investigation, launched in 1991. This time, Michael Skakel was arrested, charged, and convicted of Moxley’s murder. Again, claims surfaced suggesting that Skakel received special treatment at the hands of the criminal justice system.

In one instance, the Hartford Courant ran a story while Skakel was in prison awaiting sentencing. According to the account, Skakel, in violation of prison policy, was admitted into treatment programs without waiting time and was allowed direct contact with visitors. Michael Sherman, Skakel’s lawyer at the time, denied the claims. “Sometimes the system has to be a little flexible, but it isn’t bending over to accommodate him,” he said. Some months later, in January 2003, Skakel’s cousin Robert F. Kennedy Jr. wrote his own article, for the Atlantic Monthly, claiming that Skakel had been railroaded by the media and wrongly convicted.

Throughout his time in prison, Skakel maintained his innocence but lost a series of attempts to gain new hearings and parole. In October 2013, he finally convinced a Connecticut court to grant him a new trial on grounds that his representation in 2002 was inadequate. He was released on bond of $1.2 million.

Michael Skakel stands outside a courthouse in Stamford, Connecticut, on November 21, 2013, after being released following a hearing.

WHO KNEW?

In 2013, teen Ethan Couch was tried for causing a drunken crash that killed four. An expert witness testified that Couch was a victim of “affluenza,” or living a privileged life. He pleaded guilty to intoxication manslaughter.

RICH MAN, POOR MAN

Do the wealthy kill differently?

Killers of different social classes tend to murder in recognizable patterns, according to a 1979 study by researchers Edward Green and Russell P. Wakefield published in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology.

PATTERN ONE

Killer most often white male over 30

Crime usually premeditated

73% are intrafamilial homicides

27% are followed by suicide of perpetrator

Method mainly shooting; rarely stabbing

Alcohol rarely a factor

Usually takes place between 8 PM and 2 AM

Most likely to occur at the victim’s home

PATTERN TWO

Killer most often black male under 30

Crime often spontaneous

24.7% are intrafamilial homicides

0.8% to 9% are followed by suicide of perpetrator

Method may be shooting or stabbing

Over half are alcohol related

Usually takes place between 8 PM and 2 AM

May occur at the victim’s home or elsewhere

THE PRICE OF FREEDOM

When it comes to navigating the justice system, family wealth can really help.

ISSEI SAGAWA

Japanese Ph.D. candidate

Accused of murder, 1981

Issei Sagawa, who came from a wealthy Japanese family, was 32 years old and living in Paris in 1981 when he was accused of murdering a Dutch woman and consuming parts of her body over several days. Sagawa was declared unfit to stand trial. In 1986, Sagawa checked himself out of a psychiatric facility. He lives in Tokyo and has written books about the murder.

JORAN VAN DER SLOOT

Dutch student

Murder suspect, 2005

Joran van der Sloot made headlines in 2005 after American teenager Natalee Holloway disappeared while vacationing on Aruba. Van der Sloot, whose father was a prominent judge on the island, was a prime suspect in the case but he was released without charges. Holloway’s disappearance remains unsolved. In 2010, van der Sloot pleaded guilty to murdering a Peruvian student and was sentenced to 28 years.

WHAT HAPPENED?

THE ANGUISH OF THE COLD CASE HAUNTS FAMILIES AND LAW ENFORCEMENT ALIKE.

The lack of closure in unsolved cases can be devastating to those left behind, but about 6,000 murders remain unsolved in the United States and there are about 87,000 missing persons. Here are some haunting examples.

Family and friends of slain NBA basketball player Lorenzen Wright grieve during a memorial service at the FedExForum in Memphis, Tennessee, 2010.

A Fallen Star

The words in the 911 recording are difficult to make out, but the danger is unmistakable. On July 19, 2010, emergency operators near Memphis, Tennessee, got a disturbing call: A barely audible shout from an unidentified man, a volley of gunfire, and then nothing. Nine days later, a bullet-riddled body was found in a wooded area in Memphis—the location from which the call was placed. The victim was Lorenzen Wright, a 13-year NBA veteran who had most recently played with the Cleveland Cavaliers. He had been missing, but his disappearance had not been connected to the 911 call made from his cell phone.

Talented, handsome, and active in his community, Wright was last seen visiting his ex-wife and their six children; he often took a shortcut from their house through the area in which his remains were found. Early on, there were rumors that Wright was somehow connected to a dangerous drug kingpin. But as of 2013, the Memphis Police Department had hit a dead end, and to this day his murder remains a mystery.

The Washington, D.C., townhouse where lawyer Robert Wone was killed

Conspiracy Theory

Who killed Robert Wone? On August 2, 2006, the 32-year-old lawyer from suburban Virginia was staying overnight at a townhouse near his office in Washington, D.C. It belonged to Joseph Price, a friend of Wone’s from college, who lived there with two other men. Wone had worked late and arranged to stay with Price instead of returning to his home about 20 miles away.

A little before midnight, one of the housemates, Victor Zaborsky, called 911. Responders arrived to find Wone, whom they later determined had been restrained, drugged, sexually assaulted, and stabbed to death. Price, Zaborsky, and the third housemate, Dylan Ward, maintained that Wone must have been killed by an intruder.

Police determined there was no evidence of a break in. The housemates seemed obvious suspects. But in the end, Price, Zaborsky, and Ward were tried for obstruction of justice and conspiracy—and found not guilty.

The Teens Who Disappeared

Bonnie Bickwit and Mitchel Weiser were young and in love when they vanished in July 1974. Bonnie, 15, was working at a summer camp in Narrowsburg, New York, a few hours from her Brooklyn home. Mitchel, 16, her boyfriend and a fellow student at a Brooklyn high school for gifted students, was home for the summer. Unbeknownst to their parents, the two had made plans to meet up in Narrowsburg and hitchhike 75 miles to the town of Watkins Glen for a concert featuring the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers. Mitchel picked up Bonnie at camp, and the two set off for the concert. It is not known if they made it to their destination, but they never came back.

Did they meet with foul play? Did they have an accident? Did they vanish deliberately? The teens came from stable, middle-class backgrounds and were bright and relatively happy. Authorities assumed they ran away together, but in 2000 a man came forward to say that he had seen the teens get swept away down a river as they splashed around for fun. More than 25 years after the incident, though, the witness could not remember which river, and the lead went cold.

The couple’s families still hold out hope for their return. Mitchel’s family maintains a listing in the Brooklyn phone book in case Mitchel should ever want to call them. A website, MitchelandBonnie.com, keeps their story alive.

A police detective in front of cold case files in a police department basement

WHO KNEW?

The National Institute of Justice defines a case as “cold” when all legitimate leads have been exhausted, which can happen in just a few months.

GOING STRAIGHT

CAN LAWBREAKERS BECOME LAW-ABIDING CITIZENS WHILE INCARCERATED?

Stonecutters in a penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia, 1909—1932. In the early part of the 20th century, hard labor was both a punishment and a rehabilitation activity to help prisoners contribute to society.

Once upon a time, prisons were hellholes of chaos where pickpockets and debtors crowded together with murderers and rapists, the sane with the mad, and men with women and children. Inmates who couldn’t pay off their jailers had to fend for themselves. Incarceration was intended to remove lawbreakers from society and punish them. If the threat of serving time turned potential criminals into law-abiders, so much the better.

By the time of the 18th century, reformers in Britain and the United States had hit on the idea of a penitentiary: literally, a place for penitence and reflection upon one’s misdeeds, where inmates could be rehabilitated. In some countries the concept spurred the creation of work, education, and therapy programs to help transform convicts into productive members of society. Opponents argued that it was impossible to reform criminals, and that rehabilitation was a pointless exercise. The debate over whether such methods work rages on today.

As part of the rehabilitation program at a prison near Pisa, Italy, the inmates operate Fortezza Medicea, an exclusive restaurant for the public. Workers include a sommelier and a pianist in for murder.

Lifestyle of Crime

Hard-line law-and-order proponents contend that recidivism—an offender’s relapse into crime—is evidence that criminals are incapable of changing their ways. In the United States, research studies show that up to 53 percent of arrested males and 39 percent of arrested females end up re-incarcerated.

In contrast, advocates of rehabilitation maintain that correctional systems themselves are the problem. Life on the inside is violent and corrupt, and crime proliferates. Many inmates are forced to hone a range of unsavory skills, and return to society more dangerous than ever. Ex-cons face steep challenges in employment, housing, and family life, and must rely on criminal knowledge and contacts to get by. Many end up back in prison.

Getting to the Root of Relapse

Despite fundamentally different ideas between hardliners and progressives on the goals of the penal system in general, the reduction of repeat offenses is an objective that both sides can agree on. To this end, recent research emphasizes the need to distinguish among the kinds of approaches that have been used, in order to more effectively evaluate what really works.

Punitive measures, like electronic monitoring of ex-cons, strict probation, and “scared straight” programs for juvenile offenders, wield the threat of punishment in an attempt to deter individuals from turning to crime. However, studies have concluded that these methods have generally not had any significant impact on the rate of recidivism.

Proactive efforts, like in-prison GED and education programs, vocational training, and life-skill training, seek to instill inmates with a basic understanding of how to function effectively in society, manage money, and be a good parent, among other skills. They have shown a modest amount of success overall, resulting in a decrease in the recidivism rate of 10 percent, as compared to offenders who have received no rehabilitation.

So what does work? The most effective strategies so far have focused on finding accurate predictors of the problem—such as antisocial values, associating exclusively with people who view crime as an acceptable or admirable way of life, and psychological issues such as lack of impulse control. With an eye toward correcting these specific indicators, research suggests that tailoring rehabilitative efforts to offenders based on their skills, IQ, and other particular needs is the way to go. Treatment includes cognitive-behavioral therapy to train them in more positive ways of thinking and acting, as an alternative to the antisocial behaviors and criminal values. This approach demands more experienced staff and specialized training, as well as follow-up care after the offender has finished the program, and is expensive. However, studies have shown this type of targeted solution to decrease rates of repeat offenses by around 25 percent.

FAME: THE PREQUEL

A number of well-known music and film stars with criminal records have also had successful professional careers.

TIM ALLEN

BEFORE: Pleaded guilty to drug trafficking. Served two years, from 1979 to 1981, in a federal prison.

AFTER: Star of hit television series Home Improvement and films including Toy Story and The Santa Clause.

CHARLES DUTTON

BEFORE: Pleaded guilty to manslaughter. He served seven and a half years in prison in the 1970s.

AFTER: Stage and screen actor, star of television series Roc.

ELLA FITZGERALD

BEFORE: Bordello lookout and mob numbers runner. Spent 1932 to 1934 in reform school.

AFTER: Jazz vocalist who released 70-plus albums, sold 40 million records, and won 14 Grammy awards.

MARK WAHLBERG

BEFORE: Received two-year suspended sentence for assaulting two Vietnamese men near Boston in 1988. He served 45 days in jail.

AFTER: This former teen pop idol has become an Oscar-nominated actor and a movie and television producer.

NICK NOLTE

BEFORE: Convicted for assisting in the sale of counterfeit documents in 1962. He was given a suspended sentence.

AFTER: Oscar-nominated actor featured in 70-plus films, including 48 Hours, The Prince of Tides, and Affliction.

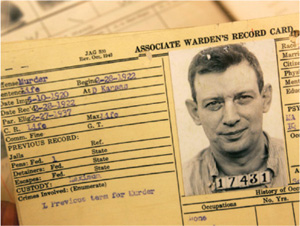

Prison records for Robert Stroud, who became known as the Bird Man of Alcatraz.

BIRDMAN BEHIND BARS

Violent psychopath Robert Stroud died in Alcatraz, but his story flew free in a popular novel and movie

One famous, semi-rehabilitated convict was Robert Stroud, also known as the Birdman of Alcatraz. Diagnosed as an incurable and violent psychopath, Stroud began serving a life sentence for multiple murders in 1909 and spent most of his sentence in solitary confinement. After rescuing three abandoned sparrow chicks and fostering them to adulthood in his cell, Stroud’s curiosity was sparked. He went on to raise and care for almost 300 canaries and to teach himself ornithology.

From prison, Stroud published two well-regarded books about bird diseases, discovered a cure for a fatal avian infection, and ran a successful business selling birds and bird medicines. His story fascinated the outside world and Stroud became a celebrity. But he never was truly rehabilitated, and remained aggressive, defiant, and detested by his fellow convicts and prison staff until his death in 1963. The movie The Birdman of Alcatraz, starring Burt Lancaster, offered a fictionalized account of Stroud’s life. Although it came out a year before Stroud died, he was never allowed to see it or to read the novel upon which it was based.

BAD GUYS GONE GOOD

REFORMED CRIMINALS CAN BE THE MOST EFFECTIVE CHAMPIONS OF JUSTICE—PERHAPS BECAUSE THEY UNDERSTAND THE IMPULSE AS WELL AS THE TECHNIQUES.

Frenchman Eugène François Vidocq founded what is considered the first private detective agency.

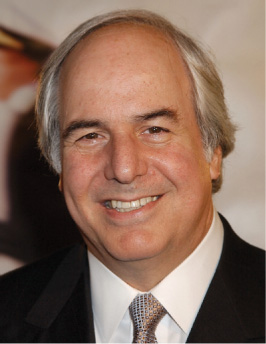

In the 2002 movie Catch Me If You Can, Leonardo DiCaprio stars as a con artist who poses as an airline pilot, a doctor, and a criminal prosecutor to make millions of dollars, all before he’s old enough to vote. It’s not just the work of some screenwriter’s imagination: The story is based on the experiences of real-life grifter-turned-crimestopper Frank William Abagnale Jr.

One of the most notorious impostors ever, Abagnale pulled off his first identity switch in 1964, at age 16, posing as a first officer for Pan American airlines. Over the course of two years, Abagnale backed up the captains on more than 250 flights and logged one million flight miles, even though by his own admission he “couldn't fly a kite.” He next signed on as a pediatrician at a hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, for a year, relying on interns to do most of his work. Then he put together a counterfeit transcript from Harvard Law School, passed the Louisiana Bar exam, legitimately, and went to work for the state’s attorney general.

Abagnale eventually served time in France, Sweden, and the United States before agreeing to help the FBI catch check forgers in exchange for early parole. He now runs a financial-fraud consultancy firm and works with the FBI. He is just one in a long line of felons who’ve turned their bad-guy ways into lucrative careers on the other side of the law.

A Very Expert Witness

Who knows better than a felon how a felon’s mind works? Forensic psychologist Paul Fauteck’s public school education ended at 15 when he was caught stealing from classmates. Charges on weapons, auto theft, burglary, smuggling, and counterfeiting followed, until Fauteck decided to reinvent himself at 24, while serving time in a federal prison.

Frank Abagnale’s life inspired the movie Catch Me If You Can.

Upon his release, Fauteck worked at a number of jobs before returning to school and eventually earned his master’s degree, in 1976. He practiced psychotherapy in Chicago and over time gravitated to work as a forensic psychologist and expert witness. In 1992, Fauteck was granted a presidential pardon from George H. W. Bush. He has since become a self-help guru to ex-convicts and a prominent advocate of prisoner rehabilitation programs.

Conquering Son of Kings

Before he was out of his teens, Frizzell Gray (b. 1948) had fathered five children and landed in jail in Baltimore more than a few times. At 23, Gray decided to make something of his life and returned to school. He eventually graduated from Morgan State University with high honors and earned a master’s degree from Johns Hopkins. In the early 1970s, Frizzell Gray changed his name to Kweisi Mfume, which translates as “Conquering Son of Kings.” Mfume went on to serve on the Baltimore City Council, win election to Congress for five terms, and serve as president of the NAACP. In 2013, he was named the new chair of the Board of Regents of his alma mater, Morgan State University.

Father of Criminology

From the cast of CSI to police around the world, the modern-day detective owes a debt to a 19th-century hoodlum, Eugène François Vidocq.

Born in France in 1775, Vidocq fell in with a rough crowd as a teen and became a petty thief. He enlisted in the army, then deserted it, returning to a life of crime as a swindler, forger, and duelist. Vidocq spent time in prison and on the lam, but when he was arrested at age 34, he offered the police his services as an undercover informant. Within a few years, Vidocq had set up a plainclothes brigade that helped reduce the Parisian crime rate. The model was soon adopted in cities all over France, and in 1833 he founded what is now considered the world’s first private detective agency.

Vidocq often hired ex-convicts who knew their way around the criminal underworld, and introduced tactics such as criminal profiling, ballistics, and crime scene investigation. He was among the first crime fighters to set up a forensics laboratory.

Vidocq’s exploits inspired Victor Hugo’s Jean Valjean and Inspector Javert in Les Misérables(1862), as well as the detective in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), thought to be the first detective story ever written.

FUNNY STUFF

Even comic heroes switch sides.

• The Prowler: In the Spider-Manseries, Hobie Brown becomes a thief known as the Prowler after losing his job as a window washer. But he switches back to the good-guy side after Spider-Man talks him out of a life of crime.

• Emma Frost: Marvel telepath Emma Frost, once known as the White Queen, started off as an evil foe of the X-Men. But over time, she has become one of its central leaders.

• Puss in Boots: In the film series Shrek, this feline assassin with deadly claws is hired to murder the green ogre. After a nasty fight, Puss confesses the plan and teams up with Shrek and his entourage.

AMERICAN INJUSTICE

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THE LEGAL SYSTEM GETS A VERDICT WRONG?

Huy Dao of the Innocence Project stands among files of prisoners hoping to be exonerated.

James Bain was sentenced to life in prison for the 1974 kidnapping and rape of a little boy in Florida. It was a horrible, dehumanizing crime, and the sentence appeared appropriate—except for one thing: Bain didn’t do it. He had an alibi and no criminal record. Police began questioning Bain, then 19, after the victim’s uncle implicated him.

Human beings are fallible, the scales of justice aren’t always balanced, and in spite of the sophistication of the U.S. justice system, innocent men and women end up in prison. Studies estimate that between 40,000 and 100,000 innocent people are currently behind bars, some of them on death row.

One organization working to change that is the Innocence Project, a New York nonprofit that uses DNA profiling to exonerate the wrongly convicted. Founded by two defense lawyers in 1992, the group and its spinoffs have helped to free more than 300 innocent prisoners nationwide. In 40 percent of those cases, the DNA profile used to help overturn the wrongful conviction also led to the discovery of the true perpetrator.

Genetic “Fingerprint”

In DNA profiling, a sample of an individual’s cells is collected via a swab of the inside of his or her cheek, or from other bodily fluids or tissue samples. The genetic material within the cells is then analyzed and compared with DNA evidence found at a crime scene. Because everyone’s DNA is different (except in the case of identical twins), DNA profiling, though not foolproof, is considered the most reliable way to identify or rule out the perpetrator of the crime.

The Innocence Project’s work with DNA takes aim at a flawed legal system, one that they point out is stacked against certain races and socioeconomic groups. More than 60 percent of the Innocence Project’s exonerees are black; most are also poor. The organization has issued recommendations to help make the system more foolproof, including the videotaping of interrogation sessions and the revamping of police lineup procedures so that they are conducted more fairly.

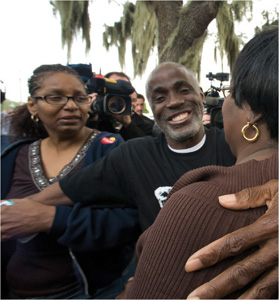

Family members greet James Bain, center, outside the Polk County Courthouse in Florida after his release, 2009.

Justice (Re)done

James Bain was one of the Innocence Project’s success stories. Bain had unsuccessfully requested to have his case reopened five times when the Innocence Project of Florida stepped in to help him get the DNA testing he had asked for. (The perpetrator’s bodily fluids had been found on the victim’s clothing in 1974, but DNA technology did not exist back then.) The DNA profile showed that Bain could not have committed the crime, and in 2009 a Florida judge signed an order to set Bain free.

In all, Bain had spent 35 years in prison, but he told a college audience in 2011 that he was moving forward. “What can I do about yesterday?” said Bain, who had recently married and, at 57, become a father. “I can only live for tomorrow.”

WHO KNEW?

Only 5 to 10 percent of criminal cases include physical evidence that can be used for DNA testing.

WRONGED MAN

He spent 16 years doing time for a murder he didn’t commit. Now free, Jeffrey Deskovic is trying to change the system.

Jeffrey Deskovic was only 17 in 1990, when he was sent to maximum-security prison for raping and killing a 15-year-old girl. DNA evidence found at the scene wasn’t a match to Deskovic. But the jury convicted him of killing Angela Correa, who had been a high school classmate at Peekskill High School in New York, based on a false confession.

Deskovic said the police coerced him into admitting to the crime. “I made up a story based on information they had given me during the course of the interrogation,” Deskovic said in a 2013 interview. “By the police officer’s own testimony, by the end of the interrogation I was on the floor crying uncontrollably in what they described as a fetal position.” Deskovic filed seven appeals but wasn’t freed until 2006, after the Innocence Project got involved. The DNA at the crime scene was retested and found to match a man named Steven Cunningham, who confessed. Since Deskovic’s release, he has earned a master’s degree in criminal justice and established the Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice. He has partially funded the group with some of the settlement he received for the wrongful conviction.

Jeffrey Deskovic

MISTAKES WERE MADE

The most common reasons for wrongful convictions

Witness errors play a part in almost three-quarters of wrongful convictions, according to the Innocence Project. Witnesses generally don’t make these mistakes on purpose; it’s just that memories can be faulty. Here are other common causes for faulty convictions:

• Unreliable or phony forensic evidence

• False confessions

• Negligence, fraud, or misconduct by the police or prosecutors

• Bad information from informants

• Ineffective, overburdened, or incompetent defense lawyers

SOURCES: *The Pew Charitable Trusts reports, 2014, 2013. The United States Department of Justice; bjs.gov.

The United States has one of the largest prison populations in the world, but the majority of the states have reduced their incarceration rates in recent years. Thirty-one states recorded overall declines in imprisonment rates between 2007 and 2012, with 15 of those states reporting drops of 10 percent or more, according to a 2013 Pew Charitable Trusts report.

The decline in incarceration rates fits into a broader decrease in crime rates across the United States. Between 1991 and 2012, the crime rate in the U.S. has fallen 45 percent, according to a 2014 Pew Charitable Trust report. But trends in incarceration rates and crime rates do not always dovetail. For example, crime rates in both Arizona and Maryland fell 21 percent from 2007 to 2012. But over the same period, Arizona’s imprisonment rate grew 4 percent while Maryland’s declined 11 percent.

STATES WHERE RATE OF IMPRISONMENT DROPPED 2007–2012*

Hawaii –20%

Massachusetts –20%

Connecticut –19%

Rhode Island –19%

New Jersey –16%

New York –14%

South Carolina –13%

Nevada –12%

Michigan –12%

Alaska –11%

Maryland –11%

Texas –11%

Wisconsin –10%

STATES WHERE RATE OF IMPRISONMENT INCREASED 2007–2012*

West Virginia +12%

Pennsylvania +10%

Illinois +8 %

Alabama +5%

Louisiana +5%

South Dakota +5%

BEHIND BARS

Some statistics about the U.S. prison population in 2008–09, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

There were nearly 2.3 million inmates.

The U.S. housed a quarter of the world’s prison population.

Approximately 3,250 U.S. inmates were on death row.

More than 140,000 U.S. inmates were serving life sentences.

The average U.S. prison sentence was 5 years.

1 in 104 Americans were behind bars, but rates varied by racial background:

1 in 106 were white men

1 in 36 were Hispanic men

1 in 15 were African-American men

CLEANING UP THE SCENE

THE GRISLY TASK OF DECONTAMINATING A CRIME SCENE OFTEN FALLS TO WORKERS WITH HAZMAT GEAR AND STRONG STOMACHS.

Officers carry the remains of a victim who had been aboard the Malaysia Airlines flight shot down over Ukraine in 2014.

The emotional aftermath of a crime lasts a lifetime, but in the hours immediately following the collection of evidence and questioning of witnesses, someone has to clean up. That responsibility may fall to the victim’s landlord or bereaved friends and family. Or, relatives may call one of the private companies that specialize in Crime and Trauma Scene Decontamination—CTS decon for short.

CTS decon is a unique type of cleaning that involves handling hazardous waste as well as dealing compassionately with distraught clients. The job is not for everyone. Often, decon technicians have had experience as nurses or emergency medical technicians or have served in the military. They’ve developed coping tools and are able to detach emotionally from what they’re seeing and doing.

Much of it is quite gruesome. A CTS decon crew might be called in to restore a home, office, or car after a homicide or assault. More commonly, they are scrubbing up after someone died alone at home and was not discovered for days or weeks. Technicians contain, remove, and properly dispose of blood and other bodily fluids. They may have to remove bone fragments from walls or collect body parts left behind by the medical examiner. And all of it must be done with the utmost discretion and care, to protect the health and safety of the living.

Germs and Poisons

The job can be dangerous. Blood, officially classified as a biohazard, can carry pathogens such as HIV and hepatitis. The chemicals used by investigators to detect fingerprints or tiny amounts of blood can leave a toxic residue. If the crew happens to be decontaminating a methamphetamine lab, they’re exposed to extremely poisonous chemicals that can be absorbed through the skin.

To protect themselves, technicians routinely wear full-body coveralls, gloves, boots, and respirators; use hospital-grade disinfectants; and sometimes clean with hands-free equipment such as power sprayers.

Why would anyone go into this line of work? For starters, the pay is good, especially for a job that does not require a college education. CTS decon companies may charge $250 or more an hour, plus additional fees. Individual technicians can make as much as $80,000 a year. But there’s an emotional component, too. Most CTS decon workers view themselves as “second responders” who continue the work the police began while helping bereaved families begin to heal.

WHO KNEW?

At more than 15 miles long, the crash site of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which went down in Ukraine in July 2014, was one of the world’s biggest crime scenes.

A decontamination crew dressed in hazmat suits stands outside a crime scene.

THE WOMEN IN THE TYVEK SUITS

Who are the real people who do this kind of work?

The 2008 movie Sunshine Cleaning took a fictional look at a pair of sisters who start a crime-scene decontamination business. The film was inspired by a 2001 National Public Radio profile of Theresa Borst and Stacy Haney, owners of Bio Clean near Seattle, Washington. The two met in the 1990s. Both were married moms; Borst had been a house cleaner, while Haney was a Boeing engineer who’d been laid off. Both were volunteers for Shonomish County Search and Rescue, an emergency service that helps find lost hikers. After hearing in a lecture that crime scene cleanup most often fell to family members, the two got hazardous-waste certified and launched their company.

“From taking something that looks so horrific and putting it back like it once was, plus cleaner, you know, we feel good about that,” Borst told All Things Considered.

NO SUCH PLACE

Sometimes the only way to rid a property of its horrible past is to destroy it.

Certain killings are so upsetting and so widely publicized that the site where they took place becomes tainted. These crime scenes have been razed.

THE SHARON TATE HOUSE

The French Country-style home at 10050 Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon, Los Angeles, was the site of the chilling Manson Family murder of actress Sharon Tate and four others in 1969. The house remained standing for a while after the murders and Trent Reznor from the band Nine Inch Nails rented it in the early 1990s. It was demolished in 1994 and replaced with a new home and a new address: 10066 Cielo Drive.

The Heaven’s Gate House

In 1997, the leader and 38 members of the Heaven’s Gate cult attempted to reach an alien spacecraft by committing mass suicide. They were found in a 9,200-square-foot mansion at 18241 Colina Norte, Rancho Santa Fe, California. Afterward, the neighbors in this wealthy area bought the home for pennies on the dollar, had it razed, and changed the name of the street to Paseo Victoria.

John Wayne Gacy’s House

The 1970s rapist and serial killer tortured and murdered more than 30 victims at his modest ranch-style home at 8213 West Summerdale Avenue in Des Plaines, Illinois, and stored 29 of the bodies in the house’s crawl space. The property was demolished in 1979 and the lot remained vacant until the late 1980s. Now, there’s a new house there with the address 8215 West Summerdale.