A new record to promote gave Nico an ostensible purpose to tour. Demetrius interpreted it to me as an obligation. Having been featured heavily on the record I was now morally obliged to support Nico and promote her career. What, I asked him, was Nico’s obligation towards me? He searched for an answer. For once, Dr Demetrius was out of words. I helped him: ‘Money.’

I wanted to be paid properly, as did everyone else that played with her. I’d been getting, at best, £30 a night. ‘A night’ means: pick up the instruments, load them, lug them; pick up the personnel; travel in discomfort, perhaps London to Glasgow; set up instruments (pianos are heavy); soundcheck (sitting around in a cold hall waiting for Nico to get herself fixed, listening to drummers ‘get their sound balanced’); find hotel; gig; pack up instruments and reload them; search for all-night gas station to buy Nico’s cigarettes. Sixteen hours for thirty quid.

Not enough.

Demetrius was adamant. I went to Nico – she wasn’t interested, as long as she got her fifty per cent of the gig fee. Since she was already getting the publishing royalties from the album – the shows being supposedly a showcase to encourage album sales – I felt she ought to split the gig money equally between everyone.

Demetrius would say, ‘But you’re not famous – try doing it without her.’ I’d labour the point that she was getting all the record royalties and the fan mail, which was fine. I just wanted paying.

When Demetrius fixed up an enormous tour that would include the Iron Curtain countries (except the U.S.S.R.), Northern Europe, Spain and then, possibly, Australia and Japan, I dragged my feet.

‘Get another piano player to learn all the parts.’

When Nico realised that this would entail having to rehearse, work with and remunerate a total stranger, she relaxed her grip on the swag a little. We got upped to £50 per show. Big time.

Demetrius reckoned this would be the first time a non-mainstream rock act had been to the Iron Curtain. Nico was worried that she wouldn’t be able to score. She knew there was some stuff around but connecting could be a problem. I reassured her that anyone who had it would come and seek her out, top junkie, Queen of the Road.

About this time I’d become involved with a Norwegian girl called Eva. It was one of those long-distance impossibilities, doomed to extinction from the start. She worked in a strip show in Stockholm, as well as turning the occasional trick if times were hard. She’d been writing and illustrating her exploits since the age of sixteen when she ran away from home in Oslo after being raped by her grandfather, a Mauthausen survivor, and had gone to live in a sex commune in Austria. My English suburban sensibility felt a bit out of step with a history like that.

The phone at Effra Road had been disconnected; Demetrius had ordered a new one under the name of Dr J. Mengele, but it hadn’t been installed yet, so I was obliged to call Eva from a street payphone. I was trying to reach numbers in Stockholm and Oslo from a callbox on Brixton High Street, whamming in 50ps every ten seconds, hippies pestering me for change. Hopeless. It would be a relief to get on that tour bus.

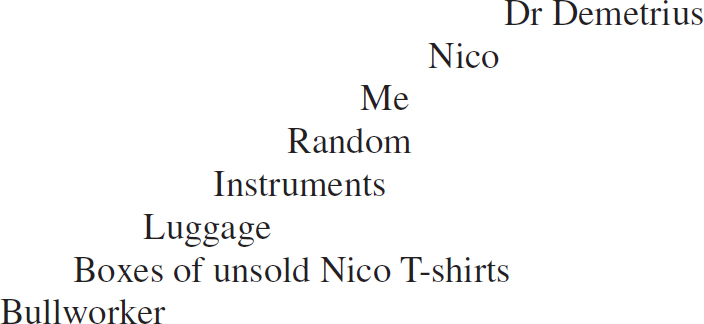

Now that we’d become less squeamish about the Great Unmentionable (money), Demetrius gave me a rough breakdown of the tour. As the musicians’ fees had been increased, economies would therefore have to be made elsewhere. One of the chief bugbears was transport hire. That could amount to around £500 a week. One ruse Demetrius had employed in the past had been to hire a bus on the understanding that it would be just for U.K. travel only … we’d therefore be in illegal possession of a vehicle and without the appropriate insurance. This was felt to be particularly unwise for Eastern Europe. I suggested he buy a bus. Vehicle hire for an eight-week tour would add up to about £4,000. He could buy a decent Talbot tourer for around £5,000. He slapped £500 down on one and off we went.

Eric Random

Da-Ga-Di-Di Da-Ga-Dum

Da-Ga-Di-Di Da-Ga-Dum

Do Da De Ge

Do Da De Ge

RIPPPP!

Demetrius flung the cassette to the back of the bus.

‘That stuff’s dangerous!’

We had a new recruit, a tabla player from Manchester, called Eric Random. Eric had been part of the early eighties Manchester Scene. First hanging out with Pete Shelley of the Buzzcocks, who wrote a song about him called ‘What do I Get?’; then as one of Shelley’s Tiller Boys; and latterly forming his own punkadelic group, Eric Random and the Bedlamites.

Eric had swung this way and that. Shelley had tried to grab his pendulum, but the little fella was hard to catch. Slippery as a tube of KY, petite, with shiny black hair and a bone structure that Vogue models would kill for, Eric would provide an essential element missing since Echo’s departure – Cool. He didn’t actually ‘play’ those tablas, nothing so crude, he seduced them as they sat coyly on a riser above the stage. First he’d remove the heavy black silk drape that protected them, then he’d shower their skins with baby talc. He’d sit cross-legged, in his own spotlight, Tantric medallion gleaming on his neck. An instant harem of adoring females would gather around his corner of the stage.

Random had spent some time in the Himalayas, smoking bongs, climbing personal mountains. He’d put himself in touch with some of the higher experiences but now he was ready to come down and get shagged.

Though Random had been talent-spotted by Demetrius, the Doctor’s new protégé drove him crazy with the Indian music. He genuinely found it psychologically distressing – too linear, abstract, he liked words that you could sing along to, stuff rooted in the common clay. Great clouds of marijuana smoke would come wafting from the back of the bus as Random puffed massive lungfuls from a chillum improvised out of a Coke tin. He’d drink the Coke (breakfast), then immediately get to work bending and shaping the tin into a pipe, scraping away the paint and piercing little holes in the aluminium to accommodate the hash. One day archaeologists will be digging up Random’s tins and reinterpreting them as unique counter-cultural artefacts.

Nico thought he was cute.

‘Oh, Eric,’ she’d say, in a singsong voice, ‘have you got a little bit of haash?’

He’d give her a piece to roll one of her individual-size joints.

‘You see,’ she’d pointedly tell Demetrius, ‘Eric knows what I need to be happy.’

We decided to decorate the new bus in a manner suited to kings of the road. We bought some stick-on girlie pinups from a French gas station, a dangling Saint Christopher and a luminous madonna, and a great Fire Eagle to stick on the bonnet. We got to the van next morning – Nico had been so incensed that for the first time in years she’d got up early and taken them all down, except for the Eagle, which couldn’t be removed. Within twenty-four hours, though, she made her own contribution to the bus decor by setting her ashtray alight and burning the upholstery.

Demetrius the commander, Raincoat the driver, plus passengers Nico, me, Toby, Random and a sound engineer from Ashton-under-Lyne called Wadada. Wadada had spent a lot of time mushroom-picking up on the Saddleworth Moors. He believed that all phenomena could be divided into two categories of good and evil: ‘Devil’ and ‘Righteous’. Meat was ‘devil-food’ and Nico’s act was ‘devil-music’. Demetrius had also taken him on as a reserve driver, but he was too shortsighted to see the road clearly. Wadada had recently been in Kingston, Jamaica, producing the great Prince Far-I, but had to return to Babylon after Prince Far-I was murdered.

En route to Yugoslavia we did a couple of warm-ups, spaced out just far enough to pay the gas, hotels and smack. The gigs were nothing special, but:

Paris

Demetrius had gone off to buy some cakes. He hated this kind of thing. Nico pressed the buzzer. The lobby door opened. Nico, Random and I entered the handsome marble foyer of an apartment block in one of the more fashionable arrondissements. There was a bowl of glacé mints on a smoked-glass table. Nico stubbed out her cigarette.

Mirrored lift. Bach Double Violin Concerto serenading us to the top floor.

We stood in the hallway. The fish-eye spyglass darkened for a second. Then the unlocking began. First the mortice, the bolt, then the door creaked open a couple of inches on a chain. Nico peeked her nose into the crack.

‘It’s me, Nico.’

The door opened on to a scene of pure devastation. What had once been a chic pied-à-terre for the discreet lunchtime affairs of the Parisian haute bourgeoisie had been reduced to a microcosm of Beirut. The walls were smoke-blackened. The curtains eaten by fire. The sofa and chairs charred and disembowelled. The kitchen was piled high with the solidified remains of a hundred spaghetti dinners. The sweet, pungent reek of lactic acid and stale parmesan vomit cut through the all-pervading smell of burning.

In the far corner, crouched by the gutted TV, was a woman of about twenty-five pushing forty-five. A curtain of henna’d hair half covered her face, the other half was a mass of scabs and running sores. Her arms were bare and crisscrossed with needle scars. Her legs likewise.

‘Monica?’ said Nico.

The girl made an effort to look up in our direction. Just then a male voice from behind us said in English, ‘If you come for ze stuff zere’s nossing. Ze bitch ’as’ad it.’

A small guy in a leather blouson, with greying hair, stepped from behind the door. He strode across the room and dragged the girl to her feet by her hair. ‘Salope!’ He smacked her across the face. She didn’t flinch.

‘Excuse me …’ I said.

‘You shoot your mouse.’

Random and I made a move towards him. He reached into his jacket and pulled out a gun, just to show us he was carrying a bit of weight, then replaced it.

‘Listen,’ said Random, ‘we’ve just popped in on the off-chance, like, of a bit o’ business.’

‘You can shoot your fucking mouse too, ass’ole.’

‘But,’ Nico pleaded, ‘I need to get straight … Monica and I will get some stuff and we’ll bring some back for you too, I promise … just don’t do that to her, pleease.’

The guy still had the girl by the hair. He was thinking.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘that sounds like the best plan …’

‘I sought I tell you to shoot it,’ the guy snarled at me.

We all stood in silence, except the girl, who was still kneeling, still held up by her hair.

‘OK’ he said, ‘ze chicks can go for ze stuff. You two wet ’ere.’ He shoved Monica’s head into his crotch. ‘Don’t come back empty-’anded, or shiz back on ze strit’ – and threw her away from him.

Nico helped the girl to the door. As soon as they opened it, a well-groomed man in a camel coat burst in, looking around in horror. ‘My God! My apartment! What have you bastards done?’ (He was the landlord and had been hovering around, waiting for someone to open the door.) He ran straight over to the guy and landed him one right in the mouth. We exited with the girl.

The bus was parked on the corner across the street. ‘Go!’ shouted Nico, once we were inside, ‘Just go!’

Raincoat slammed his foot down and we careered off down the blind alleys of backstreet Paris.

Nico and Monica scored off the street and had it cooked and loaded in a jiffy. They were true professionals.

‘Where’s Demetrius?’ I asked.

‘He’s still in the cakeshop,’ said Toby.

We turned back to pick him up. There he was, standing where the bus had been, looking a little lost, holding a prettily wrapped box of cream cakes.

He jumped into the front seat, unaware of all the drama, and opened the cakes.

‘We have a guest,’ I said.

Demetrius turned round, saw the girl, nodding out on Nico’s shoulder.

‘Care for a chocolate éclair?’ he said, offering the open box to her. The girl lifted her head slightly, her eyes rolled up, and a small blob of vomit, like baby puke, flopped out of her mouth.

Turned out the girl was the daughter of a South American movie star. Like Nico, she’d been taken up by Fellini, appearing in Casanova, and like Nico, she’d been dropped. Under the scabs and scars and the sweat-matted hair were the remnants of a real beauty. Demetrius wanted to save her. ‘Let me take you away from all this.’ But to what? To a corner cupboard in Brixton with Nico, Clarke and Echo? To a death worse than fate?

The next show was in the gingerbread town of Nuremberg in southern Germany. Needless to say we had to go and see the Zeppelinwiese Stadium, Hitler’s biggest gig. It was a huge amphitheatre, once a Zeppelin landing field, redesigned by Albert Speer, that in 1938 could hold a quarter of a million men and seventy thousand spectators. Indeed, the whole town had been one big rallying point, with one and a half million visitors for the Greatest Show on Earth. Hitler would deliver apoplectic rants from the podium (still there) that overlooked the parade ground.

The Nazi insignia have all been torn down, of course, although the impress of huge imperial eagles can still be detected in the pseudo-classicism of the arena, and the great bronze doors out of which the Führer would step to greet the massed multitudes still remain, scratched with graffiti, crude swastikas, ‘Walthamstow Boot Boys’, ‘Adolf loves Eva ’39’, that kind of thing.

Needless to say everyone had their snapshot taken on Hitler’s podium, except for Demetrius who, unable to leave the protective shadow of the bus, stood by the driver’s door in case a sudden Nazi renaissance required a quick Diaspora. Nico just stayed in her seat and whacked up a big one.

That night as we slept on crisp cotton sheets, white as a starched dirndl, Demetrius had the first of a number of fits that were to plague him throughout the tour. He said he could only think of Julius Streicher, Hitler’s Whipmaster General, stalking the town with his bullwhip, clearing it of Jews, like the medieval falconers who prepared the Emperor’s progress, flushing out the rats from his path.

Nico was as sympathetic as ever: ‘Why don’t you just go home?’

‘And rid the sacred German soil of the Eternal Jew?’

Nico shook her head. He always had to drag it down to the grudge level of national stereotypes.

‘Give me a child till the age of seven – I quote Ignatius Loyola – and he is mine for life,’ said Demetrius. ‘Hitler also employed that motto, Nico … when were you born? 1938? Let me see … forty-five minus thirty-eight why, that makes seven. Interesting.’

Demetrius decided he could do without Nico for a day and hired a Merc. Toby and I joined him. We fancied following him on his private tour of provincial cakeshops. Within ten minutes he’d damaged the car, his nerves were so bad. The bonnet wouldn’t close. We chugged off at the nearest Ausfahrt and found a cakeshop. For half an hour we sat there cakeless while the Goyim stared us out.

Back at the car rental Toby and I sat on the bonnet while Demetrius went to the office to hand them the keys. As soon as he came out we all ran for it, the bonnet yawning wide open: Deutschland Erwache! ‘Tabla player?’ said Raincoat. ‘Table tapper, more like … is there anybody there? I can’t fookin’ ’ear’im.’

Pit-a-pat-pat and Toby’s Big Bang.

‘Why can’t we have a bass player?’ I asked Demetrius.

‘Nico likes him … he looks good.’

Immediately we got into Yugoslavia, Nico and Random started fretting about the drugs.

‘Not my problem,’ said Demetrius. ‘Adventure ahead … Conquistadors of the open road!’

‘We come in search of cakes,’ said Raincoat.

We pulled up for fuel. The bus took diesel. Demetrius jumped out and shoved the nozzle into the tank and left it to feed from the bottle while he walked off … to find some cakes. Raincoat opened the sliding door, shouted to Demetrius to come and keep hold of it. Demetrius immediately self-inflated to bursting point. Raincoat was a mere minion.

‘Don’t talk to me about filling up, I know all about filling up, when you’ve been on the road as long as I have then …’

The nozzle sprang out of the tank, a writhing spitting snake of diesel. Demetrius tried to catch it but the thing was alive and wriggling furiously out of his reach. He grabbed it but stumbled, the head flipped round in his hands, and so it was that Dr Demetrius went down on the diesel. The spouting beast pumped into his mouth. Demetrius gagged and pulled away, throwing the engorged head blindly across the forecourt and into the open bus, soaking Wadada. Motorists ran for cover, grabbing their children. People were screaming. All except Nico, who just sat there staring fixedly at the empty road ahead and lit up another Marlboro.

The Yugoslavian gigs invited the truly exotic. For instance, a girl came to the Zagreb concert who’d been kicked out of her village for being a witch. Her best friend had committed suicide and they’d blamed it on her. She had the looks of a heartbreaker. Demetrius and Wadada immediately started fighting over her. Her complete indifference to them sent them into frenzies of credit-card lust.

At dinner Demetrius tried to impress Esmeralda with his knowledge of fine wines. His fingers ran up and down the list until he spotted a word he recognised. ‘I think we’ll have the Riesling.’ The girl threw a black glance at him with her dark eyes as he was about to taste it. He coughed, choked and spat it out.

‘’E prefers diesel,’ said Raincoat to the waiter. ‘Yer wouldn’t ’ave any Château Esso, by any chance?’

The little witch wanted to return with us to the West, but we were going east, to Belgrade and then up into Hungary. She’d have to hitch a ride on another broomstick.

To rid the bus of the smell of diesel we drove with the sliding door open. This irritated Nico as she couldn’t relight her dimps properly. The temperature was in the 80s as we drove to Belgrade. Demetrius was sweating it out in the thermal underwear his mother had given him and which out of duty he had to wear under his worsted three-piece and trilby. It was harvest time and the corn was being hung up to dry. The main roads were empty, but we’d still get stuck behind corn-carrying tractors. I suggested we take a side road as nothing could be as slow as these tractors – until we got stuck behind a corn-carrying horse and cart.

We drove along dirt roads, through villages with small squat houses, wooden roofs and white plaster walls with corn hanging up to dry. Oxen would stray into our path. Our progress was so slow that people started coming out of their houses to greet us. Women in headscarves, little boys in short trousers and girls in white communion dresses. They’d rush up to give us sweetmeats, candied fruit, sugared pieces of orange and plums. I didn’t know if they thought we were something special or whether they were just kinder than we were.

I wanted to get away from the bus for a few minutes, just to touch another reality for a moment. At the next gas station I legged it across the road to a wayside cafe. I ordered a beer and a slivovitz. There was only one other guy at the bar. His Lada was parked alongside the window in full view. There was a coffin in the back. I asked him who it was. He couldn’t speak English so I pointed. ‘Mama,’ he said.

Away from the hermetically sealed, artificial climate of the tour bus, life (and death) gently slapped you in the face to remind you of their omnipresence.

In Ljubljana we picked up a gypsy. At least she said she was a gypsy, and that was good enough for Toby. He had it all mapped out: the caravan, the fortune-telling booth. All she wanted was a ride to Austria. We’d already tried to cross into Hungary from Yugoslavia but they’d turned us back. (We only had holiday visas … so why, then, did we have a drum kit in the back?)

‘She’s sitting in my seat,’ said Nico, offended by the gypsy’s free and easy air. Nico wouldn’t actually address the girl directly but complained instead to Toby. ‘Come on – get her out!’ (Nico’s Central European peasant blood made her afraid of gypsies; plus, of course, there were the health warnings from Dr Goebbels.)

The gypsy had never heard of Nico, she’d just come along to the club to see a Western act play, tag along, and fuck her way west. Have cunt will travel.

Toby pulled her into the back seat with him, but she couldn’t keep still and started wandering up and down the bus.

‘Tell her to fucking sit down, or I’ll kill her,’ shouted Nico. The girl couldn’t hear Nico as she was listening to Wadada’s Prince Far-I tape on a Walkman and chewing gum.

‘Fer a pair of nylons she’ll suck yer dick all the way back ter Wythenshawe,’ said Raincoat.

We tried the cheap places in Vienna, but Demetrius scorned them. Nico didn’t give a shit, she just wanted somewhere warm with a bed, now that the nights were getting cold and the dealers hiding in their nests. Demetrius booked us into the Regina on his American Express card. The gypsy danced with joy. What the fuck was this? A little piece of heaven on the ground. She wanted to try everything. As soon as she got into Toby’s room she called room service. Toby just waved the flunkeys in, champagne buckets, plates of smoked salmon, petits fours on silver platters. A couple of hours later there was a frenzied knocking at my door. I was taking a shower, dripping in my towel when I answered. It was the gypsy. She waltzed in, wearing a Nico T-shirt and nothing else.

‘I can do deep throat,’ she said, and whisked away the towel. Within seconds she was into her party piece. ‘This isn’t such a good idea.’ She couldn’t answer. I suggested she should go back to Toby’s room.

‘Should I get another girl?’ she asked. ‘I can do that … I can make girls do anything I want.’

Next day as she waved goodbye to us on the hotel steps, Nico asked Toby, ‘Did you make her cry? You should make all the girls cry.’

‘Did you make her cry?’ became a running epigraph to such brief liaisons. ‘If Nico had been a male she’d have made the girls cry,’ pontificated Demetrius. She loved the idea of the punishment fuck. The warm, hugging stuff wasn’t really to her taste. It was all a memory now anyway.

‘Of course it’s her own sexuality she’s denying,’ he continued. Did I know that she’d been raped as a teenager in Berlin?

I didn’t.

Nico was working as a temp for the U.S. Air Force. A black American sergeant had raped not only her but other girls under his employ. She’d kept quiet about it, but he was found out and court-martialled. She had to testify for the prosecution at his trial. He was sentenced to death and shot. Nico was fifteen.

‘Not only does she have to carry the horror of the rape but the secret guilt of somehow being complicit, by her testimony, in his execution. Sex, for Nico,’ said Demetrius as we left Bergasse Strasse, ‘is irrevocably associated with punishment.’

Pecs, Hungary

Nico and Random were whingeing and wheedling, winding down the spiral staircase into pre-withdrawal panic tantrums. They weren’t actually out of dope, but they only had crumbs left and they were a thousand miles from home.

People say you can’t become addicted to marijuana. Random proved himself to be an exception to this rule. He’d smoked it every day for the past ten years, since he was fourteen. He’d never been so far away from a source.

Nico was threatening to call off the tour if she didn’t get more stuff soon.

I was consulting with Demetrius in his room about the best course of action. The phone would ring – alternately Nico and Random, each with a new and even more valid reason for not going on. With Nico it always came down to the smack, we knew it, she knew it, and she was utterly straight about it. Gear = go. With pot-heads, though, I’ve found they always try to think up some other justification outside themselves for doing nothing. (Coke-users, on the other hand, are game for anything – they just have to go to the toilet first.) There’s a self-fulfilling honesty, though, about heroin-users. They can’t pretend so easily as their habit is so obvious. The junkie’s dishonesty comes in always trying to find someone else to blame for their habit.

Demetrius and I wanted to continue the tour. So did Raincoat and Toby and Wadada. The shows had been interesting, audiences were curious. At first they weren’t so sure about what was going on. As ever they expected the living ghosts of the Velvet Underground. Piano, drums and tabla were an unusual combination of instruments for them, as well as for me. But perhaps Nico’s harmonium-centred wailing struck deeper ancestral chords and by the end of the performances they’d warmed up a bit. (If anyone can actually warm to a Nico song.)

Demetrius and I formed a delegation to Nico’s room. Raincoat was reluctant to join us. Although he wanted to stay on the tour, he’d also been ‘knockin’ on Nico’s door’ and had thus partially contributed to her depleted circumstances. He did, however, assure us that he’d do his utmost to sniff something out as soon as we got to Budapest.

Demetrius told Nico she had to continue. He made all sorts of thinly veiled threats concerning broken contracts. The more he threatened the more stubborn she became. When the legal stuff failed, he tried to get her to reconsider on moral and professional grounds. The only way to her, though, was to worm in with some sort of flattery, build her up, make her feel the fans’ disappointment. She agreed to stick it out a bit longer. She had three or four shots left, which she could eke out further with some of Demetrius’s Valium, and then there were her cottons. Random’s calls for mutiny went silent when he heard that the Good Ship Nico would steam on.

As soon as we got to Budapest the poor promoter was hammered into a corner by Nico and Random. Could he get this, could he get that? He was only a young operator, called Chabbi, still a student, he thought it was a BYO party, he hadn’t realised he had to supply the refreshments as well. He came back with a few tabs of codeine and some pal’s straggly dope plant, still in its pot. Nico necked the pills, Random grabbed the plant, stripped it down to its sad little stalks, and within seconds he was puffing away on his coke-tin, trying to get high on slow-burning nothing.

Chabbi had booked us into the local hostel, the Citadel, a converted hilltop fortress overlooking the city. The place had a splendid view of the city, but ‘not a fit spot ter feather down,’ said Toby. We stayed one night, during which Demetrius went to a private sex show with Chabbi, had another fit, and awoke covered in blood. We never saw Chabbi again.

In the distance Demetrius and I could see the glass-domed roof of the Hotel Gellert. We booked ourselves in. The glass dome opens so that the sun’s rays can shine down on an ornate swimming-pool with marble lions spouting water. There were plunges, Turkish baths, massage. For a grooming fetishist, a paradise. Of no interest whatsoever to Nico, for whom it would have been a torture chamber.

I decided Demetrius was my ally for this tour. Our addiction was to adventure and Nico could work it out for herself.

The Road to Romance

We got into Czechoslovakia by the skin of our teeth. The border control saw the instruments and Demetrius nearly blew it for us by saying we were jazz musicians, in the hope that we’d sound more innocent. But the Czech régime didn’t dig Miles. It had become their recent policy to ban jazz and imprison its practitioners.

Brno (where they manufactured the Bren gun) conformed much more to preconceived notions of life in the Eastern bloc – a sulphurous yellow light, barely illuminating empty and dusty streets. Fear. Everyone in uniform. Our conspicuousness increased our latent paranoia.

It felt good, though. It might seem a gratuitous reflection on other people’s suffering, but there was a tension here that was missing in the West. For a start, the people had strong faces, they looked like individuals, which is another thing we don’t see much of in the West. Telly and Pop sugar us up so much we still look like babies.

It was a pleasure to find my hotel room rather amateurishly bugged. And the patched sheets, cold radiators and smell of cheap disinfectant gave it that authentic penitential feel, not unlike, I imagine, an English public school.

Demetrius tried to contact our promoter in Prague, Miloscz, who every day had a different office number. ‘Nico needs something, or we can’t do the tour.’

‘What does she need?’ Miloscz didn’t know.

‘Fuel. Nico needs special fuel to keep her wheels rolling.’

Miloscz understood. We had to meet him third traffic-light after the interchange coming into Prague from the Brno road.

True to his promise, Miloscz was waiting at the appointed spot. We pulled into the hard shoulder. He beckoned a couple of us to get out. Behind a hedge he’d hidden a cache of petrol cans. Nico’s ‘fuel’. He’d interpreted Demetrius’s coded message literally and assumed Nico wanted paying in petrol.

What she needed was heroin, Demetrius explained.

‘Heroin?? My God!’ Miloscz didn’t know what to say. Why had we asked for fuel? Heroin? He didn’t want to, couldn’t possibly, have anything to do with heroin.

We took the petrol anyway, as Miloscz said we could exchange it later for diesel.

Demetrius asked which hotel we were booked in.

Hotel? Miloscz could help us find one, maybe, but hadn’t Nico’s agency already fixed that?

We followed his car into the centre of Prague while Demetrius explained the situation to Nico. My heart went out to him as he told her that the petrol cans sloshing around her feet represented her performance fee and that the heroin would not be forthcoming. As the bus rolled into Wenceslas Square Nico was at her wits’ end. She had nothing left and no one cared.

We parked up outside the elegant Hotel Europa and watched the Russian soldiers’ dismal foot patrol, followed by the occasional rusty armoured car. They were square-bashing the Czechs into submission. The oppression wasn’t so much hostile as omnivorously boring. The spotty toy soldiers didn’t want to be there, and the people didn’t want them there. For the heart of a city it sure was quiet. There were a couple of stalls selling pickled slices of some indeterminate grey fish. Apart from occasional pairs of old ladies with empty shopping bags, everyone seemed to be somehow alone. I realised when we’d all climbed out of the van that we were, in the eyes of a totalitarian régime, what constituted a crowd.

As we were directly in front of the Europa, Nico assumed it must be our hotel, and began lugging her bag towards the entrance. When Demetrius pointed out that we weren’t actually staying there, that we didn’t, in fact, have any place to stay, she gave him a mighty kick in the balls, a steel-capped castrating avenger. When the heroin was out, Nico always seemed to get sudden bursts of energy.

Demetrius doubled up, gasping for breath, his hands cupping what was left of his retracted testicles. Miloscz immediately disappeared. Passers-by smirked, but didn’t stop. The soldiers expressed a slight consternation as they goosestepped past, but they didn’t stop either. Nothing could alter the mechanical rhythm of the city’s artificial heart.

‘This is my tour,’ screamed Demetrius, emptying a bottle of Valium into his hand. ‘… Mine. She can go!’

What Nico had done, in her tantrum of self-absorption, was to inject a small shot of human emotion into the bloodstream of that tragic paralysed city.

*

Miloscz was a bag of nerves. A Czech version of Paolo Bendini. Same lack of a haircut, same TopoGigio mouse expression. A fan, with no previous experience of the wrong end of Nico’s boot, he helped us to find a couple of hotels. The East Germans were having a public holiday and they’d all flooded into Prague; most places were full, so we’d have to split up. Nico on her own – quarantined and caged; the rest of us divided around the square.

Demetrius asked Miloscz where the venue was.

Venue? Maybe it was at a colliery about twenty kilometres east of the city … he’d have to check.

Now his myriad phone numbers and addresses began to divulge their secret meaning. Miloscz was a man on the move, one step ahead of the secret police. The police were secret, so everything else in Czech life had to be. The venue was a closely guarded secret that even Miloscz would only know at the last minute.

We drove out to the colliery, down mud tracks, past smoking slagheaps. Miloscz was waiting outside, waving at us to stop. The gig had been relocated to the university, but he had some more diesel for us if we wanted to swap the petrol.

Nico was groaning and sweating, spitting a constant bile of hate, mostly in Demetrius’s direction. He accused her of Jew-baiting.

‘I am not your whipping-boy,’ he kept repeating.

We drove up to the campus. Miloscz stopped us by a wall. He urged us to be quick. We had to haul our instruments over the wall and into the nearest lecture theatre.

The place was full to bursting, the audience banked up vertically on desks so that we were nose to nose. We had to set up in front of them. There was no stage, no P.A. system, no lights other than the overhead striplighting, and no time to indulge ourselves in a soundcheck. We just plugged in and began.

The audience seemed to plug in immediately as well. They didn’t need warming up, they weren’t going to be coy with us. Nico let fly with pure screams, shredding her lyrics to pieces. We’d played for maybe twenty-five minutes when Miloscz gave us the sign to quit. The audience stamped their feet, yelled and applauded, thanked us, shaking our hands as they left. I think in that twenty-five minutes we’d all probably concentrated the best we had in us.

We hurriedly packed our instruments. The students kindly carried them down the corridor to the waiting bus for us. I got delayed talking to someone, hungry to pick my brains on some musical point or other. I’d never experienced, before or since, such interest and enthusiasm, such belief in the redemptive power of music.

As I was catching up with the rest, I cast a glance into one of the classrooms. A guy in a shiny grey suit had a hold of Miloscz by the hair and was banging his head against the blackboard. I stopped in my tracks. The door slammed shut in my face. Someone grabbed my arm – it was the student I’d just been talking to. He bundled me off to the safety of the bus.

We debated what to do – stay or go? Raincoat and Nico would remain in the bus while the rest of us went back to see what, if anything, we could do. A large crowd had gathered in the foyer, buzzing about the gig. We pushed abruptly past them to try and find Miloscz, but he was gone.

Next day, as we were drinking tea and eating ersatz cream cakes in the Europa’s café, Miloscz walked in with two cans of diesel. His face was half hanging off. One of his eyes completely closed, the other cut and blackened.

He explained that the concert had been illegal from the start. The police had been following him continuously for days – the coalmine had been a detour to try and throw them off. He was sorry for the deception, but he hadn’t wanted to alarm us or discourage us from playing. He was sorry too that Nico was unwell, but he didn’t know anything about heroin or where to get it. He hoped she/all of us would accept his apologies for the apparent disorganisation. If he’d booked hotels in advance for us that would have alerted the police sooner and we wouldn’t have even got into the country.

‘This music – dark music – is not popular with Authorities.’

We stuffed him full of tea and cakes and asked him if he wanted to come with us for a drive (we were getting insecure away from the bus). Nico was staying in her hotel, she was too sick.

‘Fuck her,’ said Demetrius. Miloscz looked surprised.

‘Nico is difficult artist to work with?’ he asked.

‘First of all, let’s get our lexical definitions straight, Miloscz,’ said Demetrius, still wounded by Nico’s castration attempt. ‘I think we can safely subtract the noun “artist” and the verb “work” from that sentence. Nico is an ar-sehole rather than an ar-tist, and she’s never done an honest day’s work in her life.’

‘Yeh, but,’ Raincoat intervened on behalf of his patroness, ‘she’s never pulled a gig yet.’

True, true, everyone nodded.

‘OK, then,’ said Demetrius to Miloscz, ‘let’s just say … Nico is a difficult arsehole to work with, and leave it at that.’

As we set off with Miloscz in the bus, we noticed a rather grand fifties black saloon quite blatantly pull out behind us. Miloscz informed us that it was the cops in the shiny suits who’d ‘interviewed’ him the previous evening.

As we pottered about the countryside north of Prague (the black saloon sulking close behind) we couldn’t figure out why there were fields of vegetables yet none in the restaurants and shops. (Nico’s vegetarianism meant she’d been subsisting on a wartime ration of carob chocolate and Europa cakes.)

‘All exported to Germany and Nederlands,’ said Miloscz.

‘Doesn’t seem right, some’ow,’ said Toby.

‘Perhaps is for the best,’ said Miloscz. ‘All vegetables contain double permitted levels of cadmium, lead and mercury. It’s better you eat only cakes.’ He chuckled, wincing with the pain in his jaw.

In the evening we went to a hotel disco – the shiny suits followed us. It was the kind of place where you get fat sausage-eating German tourists and hookers with Kathy Kirby makeup, as well as the straightforward package tourists. Demetrius perked up.

‘Have you noticed how much happier we all are when Nico isn’t around?’ he asked. We half-heartedly agreed, but the truth was we all loved to watch the fights. They were like a bad marriage – compellingly awful.

Demetrius and Raincoat fancied a spin on the dance-floor with the ‘ladies’. Raincoat sidled up to one. He pointed at her.

‘Are you …’ then he pointed to himself ‘… fer me?’

The girl smiled sweetly. Raincoat shouted over the music. ‘Right then … ’ow much?’ He wanted to get down to business quickly. The girl didn’t quite understand. He pointed at her again. ‘For you … ’ow much? … dollaris? … monneta?’ Deeply offended and hurt, she gave Raincoat a slap across the face. She was just an East German student on a cultural trip to Prague, definitely not on the game. Her parents came up looking worried, the shiny suits were agitatedly conferring amongst themselves. Miloscz slipped out. Without Nico’s sweetly civilising influence we were just English yobs abroad.

On our last morning in Prague we had nothing to spend our Czech koruna on, so we bought up lots of ‘authentic Bohemian black glass’ jewellery made from King Wenceslas’s glass eye.

Miloscz turned up with goodbye gifts of diesel for us. Hugs and kisses and useless addresses. The shiny suits looked on as we packed the van with yet more cans of fuel. There was nowhere to put our feet, so our knees were up near our chins. Nico was deeply miserable. She’d developed a suppurating abscess on her leg and spent most of her time swabbing and dressing it.

We rolled off slowly down the square, the diesel glugging ominously with every bump and lurch along the unsurfaced road. A bomb on wheels.

The black saloon followed us dutifully a few paces behind. Raincoat clocked them in the mirror.

‘’Ave they got nothin’ better ter do?’ He scrambled around in the glove compartment for a cassette, whipping through the selections, and finally settling on one. Then, joining up with the slow patrol of military, secret police and German tourist coaches, he took us on a final circuit of Wenceslas Square. The windows down, he turned Ol’ Blue Eyes up full. Russian would be a crime –’cos Nice ’n’ Easy did it every time.

*

We briefly interrupted the Eastern Bloc tour to play a few dates in Scandinavia. The gigs were a dispiriting flop, after the enthusiasm we’d encountered in the East. Nico had hit them the year before – once was enough.

While we were in Oslo I looked up my own Nordic goddess, Eva. I had a lot of hopes pinned on the meeting, despite the ‘Dear Bjorn’ letter I’d received a couple of months back. She didn’t show up at the gig, as it hadn’t been advertised, so the next day I stayed behind with Demetrius and Nico (who was sick). I went to Eva’s apartment block (where Edvard Munch once had a small studio – it had retained that tortured vibe) in the old Christiania part of Oslo. The place was being rebuilt. I asked a guy downstairs if he knew where Eva was. He showed me to another dungeonesque wing of the old grey building. I knocked – no one there. So I left a note.

‘Hello, bastard,’ she said as we met outside a pink-and-white American ice-cream parlour in the Karl Johan square. We found a corner in a nearby bar. Over brandy at £10 a shot, she fixed those ice-blue eyes on me and spelt out in block capitals how, while working at the strip joint in Stockholm, she’d got close to the other girls there. VERY CLOSE. She thought women were better to be with, more understanding. ‘Anyway. What is it you men want from us? It’s just a hole – no?’

I tried to get a cab back to the hotel. In my idiot joy at hearing Eva’s voice on the phone I’d rushed out in what I had on – a thin jacket and shirt. A great neon sign above the square flashed, as if in pride, 0°C. The Norsemen were at their revels and the taxi queue was endless. I was trembling so much from the cold and the self-pity that I just curled up on the pavement. A stranger gave me his cab and I made it back to the Hotel West, where I defrosted my misery in great pools to Demetrius. ‘Who can comment accurately on these foolish, complicated things?’ he said. ‘But it’s clear she won’t have you any more – so, here, take two of these and go to bed.’ He handed me his own personal bottle of Valium.

Next morning, still woozy from the Valium and with my broken heart tied to a ball and chain behind me, I dragged myself on to the Oslo-Stockholm train with Nico and Demetrius. This is one of the world’s great train rides, over the mountains, looking out across the fjords. The carriages are laid out like drawing-rooms with sofas and armchairs and magazines to read. ‘Go away!’ said Nico to a friendly steward offering her a complimentary newspaper. Then she scowled at me and turned on Demetrius. ‘What’s the matter with him, blubbering away like that? Pay more attention to me! Jesus … I need a shot!’

‘You certainly do, my dear,’ whispered Demetrius as the other passengers turned round, ‘right between the eyes. Can’t you see the boy’s upset?’

‘Over some silly little whore …’

Later, when she’d got herself straight, Nico sluiced her syringe clean, squirting a needle jet of bloody water into her mouth. ‘Jim … why do you get so upset? You know women are inferior.’

We rolled off the boat into the grim and sullen port of Gdansk. As we drove to Warsaw through a unique topography of puddles, empty dirt roads, cabbage fields and extinct Nazi deathcamps, a perpetual grey fog, like battle smoke, never lifted. The war was still on in Poland.

(We’d come the hard way from Malmö, Sweden, in a decrepit tub – incredibly called the Vulva – stinking of ship-grease, oil and disinfectant. There was a bar on the boat, the Sky Bar, that sold only vodka and took only hard currency. It had a disco, about six foot square. Apart from the magnificent seven of us, there were just a couple of other people in the bar, both of them hookers. The moment we sat down one of them got up from her stool and started a hideous fertility dance alone in the disco spotlight. A massive, treetrunk-legged escapee from an agricultural collective, she’d clearly received her sexual education bending over in the fields, planting potatoes, boared like a sow from behind. Her cheeks were ruddy with broken veins, her mouth thin and mean like a peasant. She looked like she knew how to wring a chicken’s neck. She stomped about to an Abba song while we looked on. Demetrius fancied a go, just to outrage Nico. ‘It’ll be like fuckin’ a bucket,’ said Raincoat.)

Wadada had a cassette of Fauré’s Requiem, for which he was working out a Dub version. Demetrius was less than enraptured.

‘Has somebody died?’ he asked Wadada. Demetrius had a very honest and pragmatic approach to music – meaning was derived from context, everything had its place. Requiems did not belong in a Talbot tour bus. He proposed Country & Western, which was made for the road. No one wanted it. Random offered to put on a tabla exposition, recorded live in Benares. Nope. We sat in silence.

Nico was still exiled in her special seat in the bus, ashtray overflowing, wrapped up in a patchwork sheepskin jacket, silent and withdrawn. The fog rolled by. We’d wipe the condensation from the windows, but there was nothing to see and nowhere to stop and eat, just grey fading into black.

Then lights started to appear in the blackness, figures, more lights. We’d drive on. The gathering of lights increased, we could begin to distinguish people, faces illuminated by candlelight, gravestones. We reasoned, as it was November 2, that it must be All Souls’ Night. In Poland, perhaps, the dead have more significance than the living. We drove on through dark and empty villages, to find, on the outskirts, the graveyards alight with humanity. It continued for a couple of hours, and even when the friends of the dead had dispersed the candles were left burning on the graves. Then it was black night again.

Suddenly Nico leapt from her seat. ‘Look! It’s Jim!’ She peered into the rolling fog. ‘I can see him …’

‘Jim’s ’ere, in the back,’ said Toby. ‘Aren’t yer, Jim?’

I reassured Nico I was there.

‘No-o-o. No-o-o … not you, Jim.’ Nico continued staring into the night. ‘Jim Morrison … I can see him … there … loook!’ She pointed out into the empty fog.

We all strained to see.

‘Where?’ asked Toby.

‘Can’t see fook,’ said Raincoat.

We carried on trying to discern the lead singer of the Doors out there in the nothingness.

‘’Ang on,’ said Wadada, squinting through his bifocals. ‘I think I might’ave clocked a visage …’

Sure enough, it was the Lizard King himself, a-writhin’ around in his black leathers, sucking off the mike, dancing us all into an early grave. Like him, we’d all died and been sent to Poland for our purple sins.

Joy awaited Nico in Warsaw in the form of a horse needle and a bottle of ‘kompot’. Kompot, so-called because it resembles a drink made from a compote of mixed fruit, is actually a kind of opium vodka, distilled from poppy heads. Poles (check your local deli) like to eat bread with poppy seeds sprinkled on top, and poppy seed cake (a kind of marble cake with poppy seed veins). Such eating habits support a sub-economy of kompot distillers, all of whom are addicts or ‘narkomanis’ themselves.

‘It’s the best hit I’ve ever had,’ said Nico, overjoyed to be back in a cultural milieu she recognised … The Living Dead.

The rest of us would have been happy with just a few of the poppy seed cakes, as we still hadn’t eaten anything other than a sandwich made from kabanos sausage – ‘devil food,’ said Wadada.

We played the same hall they use for the international Chopin competition and I used the same piano. In fact there was a bewildering choice of four Steinway concert grands. It was an absurdly grandiose and formal setting for our small thing and our performance was consequently as reserved as the seats. The audience applauded politely and looked on, serious and subdued. I think the problem was that, for once, Nico was out-doomed. It was a relief to get back to the kompot in the dressing-room, where the promoter was waiting with another kabanos sausage each for us. He was another Miloscz/Bendini type. I had them narrowed down by now. They were the brainy loners – their career opportunities would exist either in serial-killing or pop promotion.

Zbigniev, ‘Ziggy’, had a zit problem. Nico offered to squeeze them for him.

‘Wow! My God!! To be hearink zuch think from Nico, Welvet Undergron Warhola Zuperztar.’

Ziggy paid us about ten million zlotys each and then took us to our hotel for a ‘zpecial’ hello/goodbye/thankyou zupper.

A crowd was gathered around the bus, and after we were jostled and thanked and shaken and pressed we realised we’d all been dipped. Just little things – Walkmans, cigarettes, Eric Random’s hair-gel and eyeliner.

We followed Ziggy and his pals as they drove us through the 1950s time tunnel cold war ambience. You could almost hear the pompous synthesizer music and the brooding po-faced commentary.

Ziggy pulled up about twenty yards from the hotel. He wouldn’t be coming in, he wasn’t allowed … foreigners and nationals couldn’t fraternise in the international hotels. He realised it was the first opportunity we’d had for a decent meal since Sweden, so he’d wait outside for us. We watched Ziggy and his pals hanging around outside smoking while we broke our fillings on pieces of shot from the wild pheasant.

Next morning Demetrius showed up, ashen grey. He’d been wandering the streets since dawn, where the old ghetto had been, talking with ‘the ghosts of my people’.

Nico was trying to be friends again. Happy on the kompot, she’d begun to notice the existence of others and her abscess was beginning to heal. The horse needle had helped her to draw off the pus. ‘Look!’ she said to Demetrius, holding up the syringe for his approval, like a kid with her potty, ‘two ccs!’

‘My God, Nico … I think you must inhabit a separate reality from the rest of us.’ Demetrius shoved his Vick inhaler up one nostril. ‘I’ve just spent the morning breathing in the dust of 400,000 murdered innocents.’

She didn’t understand. Her leg was getting better. The kompot was great. She’d be in good shape for Berlin … Ghetto?

Berlin, Latin Quarter

‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ – a capella.

… -/---------/------,

-/------------/----,

--/----/and/-----/---/------- …

---’--/-------/----/--/-------/------!

[Permission to reproduce lyrics refused]

… ‘You’re staring down my fucking throoaat!’ Nico broke off mid-song to deal with a vampette who’d been locked on her every move. She had the audience totally intimidated – which is exactly what they’d paid for. (In contrast to the last time we’d played Berlin.) Again it wasn’t the music, but the vibe people came to pick up on. If you were a happy, well-adjusted, straight-ahead, thinking, caring sort of person, then you’d probably be satisfied with a sermon and blessing from Sting. If you were totally fucked, you were probably at the Latin Quarter.

We had to drive from Berlin to Rotterdam in one day. As all motorists had to observe the speed limit down the corridor it would mean an eight- or ten-hour journey. We were doing OK until we hit a tailback, north of Hanover. The truckers were holding a lightning strike across northern Germany, and were blocking the autobahn lanes.

We sat, waited and debated. Random jumped out and with his pocket knife tried to stab the tyres of an articulated lorry. It was about as effective as a mosquito biting the leg of an elephant. We waited. Demetrius decided he was going to get us out of this jam and to the gig on time. ‘Don’t they realise we’re entertainers? We can’t disappoint our public, we have a duty to the audience which far exceeds our responsibility to the German economy.’ He pulled us off on to the hard shoulder. The other motorists scowled at us, but before long we had a beat-up old white Audi following us full of Turkish Gast-arbeiter. This infuriated the truckers even more, and they blocked off the hard shoulder. A motorist got out of his VW, a slightly hippy type in a lilac duvet coat, and banged on the window. Demetrius wound it down.

‘You vill stop please and svitch off your engine! Ve don’t vont your pollution!’

Demetrius looked at him and slowly wound the window up in his face. ‘Even the environmentalists are only obeying orders.’ He revved the engine and turned off on to the grass verge. It was now dark, and I prayed Demetrius wouldn’t drive us into a ditch. We lumbered on at a tilt for a few kilometres, until the next exit, where we pulled off on to a small road. It was badly lit and we had no idea where we were. We drove around, probably in circles, for about half an hour, until we came to an abrupt halt before a roadsign which read ‘Bergen Belsen’. No one said anything. Demetrius just turned the bus round and we headed back to the autobahn, tucking ourselves discreetly into the mainstream of the body politic.

Amsterdam: Paradise Regained

As ever, you couldn’t find anywhere to sit in the dressing-room at the Paradiso. Most of the seats were taken by girlies, queueing up for Eric Random’s Tantric Love Juice. There was an anorexic poet called Arnaud who looked like a pierrot in a baggy white suit. He did press-ups in the middle of the floor while reciting his poems in Dutch. Nico and her group were incidental. Demetrius would let anyone he wanted in now, it was his tour. Some kind of turning-point had been reached in Eastern Europe.

‘I give therefore I am,’ he would say, and invite strangers to help themselves to our drinks. His tour, his party, his choice of companions. Nico had suddenly become extraneous, a walk-on in her own movie, carrying a hypodermic needle. The music became even more marginalised. If Nico couldn’t be congenial towards her host then she could ‘bug off’.

Dr Demetrius seemed to have grown taller and expanded even further in status. His tie was straight again. His hat fitted at last. His fits had abated, his debilitating agoraphobia held at bay. ‘Yes, James,’ he would say, ‘a man needs to keep a grip on his own potential, and not become deflected from his higher purpose in life by the mean-spirited and ungenerous, such as Fraulein Christa Paffgen.’

‘I like Nico,’ I said, ‘she’s OK … she’s funny …’ It didn’t sound like much of a defence, but then I didn’t feel that Nico needed defending.

‘A person only begins to become an individual when they cease to be the victim of their own temperament,’ said Demetrius. ‘Nico is, ultimately, despite her amusement value, a parasite.’

‘In that case,’ I said, ‘we’re all parasitising ourselves by working with her.’

‘Wherefore such cynicism, James? Do I not detect in your tone the chaise-longued ennui of the Oxford common-room? You misunderstand me, I also like – love – Nico. But I know what she is.’

‘What’s that then? You’re hip to her secrets?’

‘Not especially – though occasional confidences have been placed with me, I feel that there are no great disclosures awaiting us that will suddenly reveal a deeply warm and caring human being. With Nico I feel that what you see is what you get.’

‘That’s OK by me,’ I said. ‘There’s a kind of purity in her… in that remorseless monomania, that heroic indifference. Nico wouldn’t piss on us if we were on fire, so at least we know where we stand. The problem is, you wanted her to love you, and she can’t, so you’re disappointed.’

‘I wanted love, certainly, but I feel that Nico also needs love, despite herself. I think we all of us need to divest ourselves of who or what we think we are, to risk a certain nakedness.’

‘Perhaps some people look better with their inhibitions on?’ I suggested.

Demetrius shook his head. ‘Why is it, James, that you favour the smart riposte at the expense of authentic feeling? Dear God! The great Zero that lies at the heart of every Englishman. It’s an emptiness he tries to fill with breeding, an Oxbridge education and the cultivation of influential friends, but none of this can disguise his essential poverty in matters of the heart.’

Such were the thoughts of Dr Demetrius before Raincoat poisoned him.

We met Raincoat in one of those dope-shop/coffee-bars that stink of hippy paranoia. Demetrius stood there in his double-breasted suit and trilby – his incongruity filling the place up. He considered drug-taking a vulgar high and any form of drug dependency the sign of a weak personality. Unfortunately, though, Demetrius had not managed to curb his addiction to cakes. Raincoat was about to bite into one when Demetrius broke a piece off, without asking, and began to devour it.

‘’Elp yerself,’ said Raincoat, pushing the plate over to him. ‘Mia casa, tua casa.’

Demetrius chomped away. I had to intervene.

‘Is that what I think it is?’ I asked Raincoat. He nodded. I told Demetrius it was a hash cake and he shouldn’t eat any more, as he’d never taken a psychoactive drug in his life.

‘Tastes fine to me,’ said Demetrius, gorging himself. Whether out of bravado or sheer greed he polished the cake off. ‘I’ll see you all later. I’m off to – er – look at the Rembrandts.’

Demetrius viewed museums as ‘the graveyards of culture – wouldn’t be seen dead in one.’ I knew he was off to peruse some life studies of a more exotic nature.

Pandemonium. Raincoat and I got back to the Museumzicht, our small hotel with the eternal stairs, a couple of hours later, to find a doctor at Demetrius’s bedside, administering intra- venous valium.

Demetrius grabbed hold of the doctor’s arm. ‘I’m dying,’ he said in a state of total panic. ‘I’m dying.’

‘No, you’re not,’ said the doctor, ‘you’re just hysterical.’ He unloaded the valium into Demetrius’s arm.

The sedative began to work and the doctor left. As soon as he was out of the door Nico came in, wafting great clouds of incense over Demetrius, followed by Wadada playing Fauré’s Requiem.

‘Oh God! Oh God!’ cried Demetrius, horrified at the apparition of Nico hovering over him. ‘Get away! Get away! The Angel of Death … Get away!’

Demetrius was never really the same after that. His old anxious, misplaced self returned to claim him. The inhaler and the Bullworker became his constant companions again. They say that travel broadens the mind. Demetrius’s mind had been stretched to places it didn’t want to go. Out-of-body experiences, feelings of absurdity, paranoia, anxiety.

‘I genuinely thought I was going mad,’ he said later. ‘Apparently ingesting hashish is five times more powerful than smoking it … I’d never even had a puff of a joint before.’

He rested up at the hotel for a few days. Occasionally he’d venture outside. I’d find him standing in the middle of the road, peering through an imaginary sextant.

‘Perceptual distortion,’ he’d say. ‘Perceptual distortion.’

Then he moved to another hotel, taking the tour float with him. There, he entertained everyone with a curious charade, claiming that his room had been burgled and the money stolen. We called the police. They knew the hotel well, a perfectly straight establishment with a desk clerk and doorman. Demetrius, however, seemed anything but straight to them. According to the desk clerk he’d filled his room with a bevy of Thai callgirls, so it was easy to work out where the money had gone.

Then Demetrius left. Just disappeared.

Angel 666, Barcelona (Homage to Catatonia)

Nico, Eric Random and I had been having a disorientating time of it down the Ramblas, tripping over jugglers and bumping into mime artists. There was no room for honest scum anywhere. Eric thought he knew the way back to the hotel, so Nico and I doggedly followed him, keeping our eyes fixed firmly on his brand new, calf-length, black, Spanish bootees (size 7, ladies). One blind and black alleyway looks much the same as another in the Gothic Quarter and within minutes we were lost.

Having paid a kid to lead us out of the barrio, we arrived at the venue – Club 666 – to find ourselves enigmatically billed as ‘Nico and the Hasidim’. The mystery was solved, however, when who should walk on stage in the middle of the performance, but Dr Demetrius himself, dress as Hasidic rabbi, in long black overcoat the hat, brandishing a copy of the Bible.

‘The Angel of Death. The Angel of Death,’ he kept repeating. The audience was completely mystified. We carried on playing, like it was part of the show. Nico didn’t notice him, until he was standing up against her, staring manically.

‘The Angel of Death.’

‘What are yooooo doooing here?’ Nico asked.

Demetrius just stood there, impassively staring.

‘Get out! … Go!’

He didn’t move.

She shoved him.

He swayed a little, but remained rooted to the spot.

We turned up the volume and blasted him off.

Then he showed up again the next day at a live TV date: The Angel Cassas Show. It was in a variety theatre. A traditional sloping stage, footlights, individual dressing-rooms, the works. The stall seats had been removed and tables and chairs put in their place, so it would resemble a cabaret. The audience sat eating and drinking, while the host, Angel Cassas himself, smoothly compered an eclectic show that consisted of topless dancers, James Burke (the communicator), a Rumba troupe, and Nico. Demetrius was still carrying his Bible, and now wearing a crucifix as well as the Hassidic gear.

Nico was anxious about Demetrius’s craziness, whether he was going to pull another stunt like the night before. He was hanging around outside her dressing-room, pacing the corridor, reading aloud apocryphal passages from the Book of Revelations.

Eric Random and I sniffed about the Bluebell Girls. Though they were a permanent feature of the Angel Cassas show, half of them came from Blackburn. They had long fantails of pink ostrich feathers, worn over a sequined G-string, and up top nothing but pert, powdered, pink titties and smiles as wide and eyes as blue as an empty sky. One of them plucked a tail feather and gave it to Random. I asked him if I could borrow his Tantric talisman to see if I had any luck.

‘This’asn’t left my neck since I was in Nepal,’ he said in a hushed, reverential voice. ‘It was blessed by Baba Yoni’imself.’

We were on after the girls. Angel Cassas was giving mouth, some silky-slick patter to the middle-aged punters, getting them horny. Then Nico was supposed to come on and sing her saeta of woe.

Cue. Camera. No Nico.

We had to start playing, so we did a long intro … then a verse … but still no Nico. A third of the way through the song, we heard the clump and jangle of her boots. She stomped on stage, furious. Strangely, her dressing-room intercom had been switched off. The audience started tittering. I looked up at the backstage balcony: there was Demetrius, eating his Bible. We finished the song, the clap man signalled the audience to applaud. Above the polite patter, Demetrius could be heard admonishing us all to ‘beware the Angel of Death.’ This caused some offence to the management as they thought Demetrius was referring to Angel Cassas. I managed to calm them down, explaining that Nico’s manager was undergoing some sort of spiritual crisis and had been this way for weeks.

In all this hysteria, Nico seemed to have become strangely steady. An atmosphere of insanity seemed conducive to her sense of well-being. It made her feel normal. She was now just another person in the bus. And that’s the way she liked it. That’s who she was. One of the boys.

Digital Delight/Ringfinger Surprise

Beating the borders was always a challenge. Various subterfuges were employed as we crisscrossed our way across fortress Europe. Nico would adopt the disguise of a prim librarian – specs, hair in a bun – but unfortunately it was undermined by the black leather trousers, the biker boots and the leather bracelet with silver skulls. And, as her eyesight was perfect, the alien lenses distorted her vision so much that she could barely discern a familiar face, let alone the inquisitorial stares of officialdom.

Customs officials, it has to be said, ain’t the brightest of individuals. They always pull the broken-down old 2CVs with broken-down hippies inside, or the conspicuously guilty pop group with the pills and potions in their underpants. Meanwhile the professional hustler in the black BMW with a briefcase full of cocaine is waved on through. This prejudice infuriated Nico, to the point where she would become contemptuous of even her own fear. Once, as we were driving off the car ferry at Dover, she handed me a bunch of used syringes, a whole tour’s worth. I quickly threw them off the ramp and into the oily black water below, thanking her profusely for the macabre bouquet.

Nico’s preferred method of concealment was to buy a pack of condoms (a source of great embarrassment to her: ‘I’m sure they must think I’m a hooker when I buy these things’) and a jar of vaseline. Then she’d fill the prophylactic with a clingfilmed ball of heroin. This she would insert into her behind, generally about five minutes from the border. This is how it would go:

‘Are we ne-ar the booorder?’ We’d heard it sung so many times it had become a familiar refrain along with ‘Have you got a little bit of haa-aash?’ Out would come the condom, a look of disgust on her face. Then she’d wriggle out of her leathers. Everyone would suddenly busy themselves with displacement activities: books that hadn’t been opened throughout the tour would suddenly become intensely fascinating.

There’s a particular customs post north of Lille, on the French/Belgian border, every time … every single time …

Demetrius was whistling inanely a nerveless, tuneless ditty of his own making.

‘We’re a touring party of jazz musicians … we have a carnet … I am Miss Paffgen’s personal physician …’ It was never any use. They pulled the bus apart, seats upturned, instruments out of the cases, dirty laundry everywhere. Then the pockets – we lined up one by one, emptying our pathetic secrets on to the desk. The chief poked through the pile, saying nothing, nose twitching above his black moustache. You could picture him at home, a photo of Jean-Marie Le Pen on the dressing-table; humping his wife while she picked spinach from her teeth.

We knew what was in store, it was ritualistic and we were resigned. They probably knew it was a waste of time, but that’s what they were there in the world to do – waste our time.

One by one we were led off to the ‘interview room’. Nico banging into things, blind as a bat (the glasses had to go).

A thin little guy with rat eyes asks me to undress. He inspects each garment, examining the lining. Then he holds my arms under a lamp to check for needle marks. On the table lies a pair of surgical gloves and a tube of lubricating jelly. If you piss these guys off you don’t get the jelly. There’s a knock at the door. A female officer is standing there, a small bull dyke with cropped hair and a big black gunbelt. She’s excited, they’ve found something.

Back in the chief’s office, I ask Eric Random if he got the finger.

‘Yeh,’ his eyes lowered. ‘Creep asked if ’e could ’ave me phone number afterwards.’

Nico comes in with the dyke, looking suitably crushed and repentant.

The chief starts typing out a charge: possession of prohibited substances and unpaid debt. The central Paris computer has thrown up some ancient hospital bill Nico hasn’t paid.

They got what they wanted. A token. Nico had stashed a shot’s worth of dope in her knickers (the rest of the stuff still safely concealed in its traditional hiding place). They were happy with that. A few smiles, a few jokes. Demetrius resumed his whistling.

Fear is always a problem of scale.

Brixton

‘’Im aint naw docturr!’ Mrs Chin blocked the top of the stairs to our flat. ‘An’ she aint naw music teacher neither.’

‘An’ ’im,’ she pointed to me, ‘’im naw in the middle ages … An’ ’oo be’e?’ She pointed to the svelte figure of Eric Random. ‘What’as bin goin’ on in this’ere ’ouse aint nawbady’s bisness … like a ’erd o’ buffalo, up an’ down dese steers … Amma feart a knock on mi own door fer t’look inside … blood! Blood on de walls!’

Mrs Chin had got into the flat while we were away. Clarke and Echo had been in permanent residence, contributing their unique refinements to our Brixton salon. Needle orgies every night. The place looked like it had been gangbanged.

Echo and Clarke crept in later, after Mrs Chin had shaken the rest of us for the rent and given us our notice to quit. Needless to say, Bertie and Jeeves hadn’t paid a penny towards the upkeep of the place. The phone was off – red bills of over £500 to Dr Mengele threatening disconnection. Demetrius’s annoyance was tempered by the thought that not only did the evil doctor of Auschwitz have Mossad on his trail, but he would also have to answer to British Telecom as well.

*

Clarke and Echo had been to Australia together for a couple of weeks. Echo spelt out the hazards to me as Nico was to do the same tour imminently. He told me how the promoter had personally threatened him, accusing him of being a parasite on Clarke. Nico said, ‘You two should get married – I guess for them it’s like you’re living in sin.’

Any hints of homosexuality threw them both into a stir of Catholic homophobia. ‘It sez in the Bible,’ etc etc. In fact, for Clarke, mentioning any kind of male sexuality risked an unwanted reference to the seat of shame itself: ‘the three-piece suite, the sausage and mash – God’s cruellest joke.’

Echo reached in his jacket pocket and pulled out a couple of snapshots. One was of a girl who looked like Alice in Wonderland but with an Edgar Allen Poe twist, an emaciated child-woman who looked like she’d scratched her way out of a coffin. ‘Met ’er in Sydney, wonderful girl, ’Elena, amazin’ ’ow she’s kept ’erself tergether – yer’d never guess she was on the gear would yer?’ He showed me his other snap. ‘They’ave whales up near Brisbane,’ he said with awe. I looked at the photo, it was a picture of the empty sea, nothing else.

‘But where are the whales?’ I asked.

‘They dived,’ he said, pointing to a blank area of sea. ‘But that’s where they were.’

Echo complained of a perpetual toothache but said he couldn’t go to the dentist as he was scared of injections. Also he’d told Dr Strang back in Prestwich hospital that he was ‘sick of the bloody methadone … I want what they give prisoners – bromide. Ev’ry time I get the bus up ter Prestwich I get a fookin’ ’ard-on cos o’ the vibrations … the only way I can ged it down is ter think o’ the bleedin’ dentist.’

You’d get dizzy listening to Echo’s explanations of his life. Sooner or later he’d get round to how disloyal I’d been not quitting Nico’s ensemble when he did.

‘But you didn’t quit,’ I said, ‘you were fired.’

‘Yeh, but I wouldn’t’ave bin if you’d quit too, then it would ’ave bin proper workers’ solidarity.’

‘Workers? Nico and Demetrius fired you because you’re a junkie,’ I said. ‘She’s not your mother … she doesn’t need dependants, she’s got her own habit to look after.’

‘But after all I fookin’ did fer’er … an’ fer you.’

Nico was also turning weirder by the minute. One day I caught her rifling through my coat pockets, probably in search of cigs or a bit of change. The kleptomania reached its peak when I found out she’d pinched a love-letter of mine from Norway.

‘It wasn’t very interesting,’ she said, ‘the usual gerrl’s stuff.’

‘That’s all right, then,’ I replied, ‘just pass on the bills as usual.’

We had a red-hot row about it that became really childish. She started off with all that nymphomaniac stuff again so I called her a nosy old nun.

‘Can I have it back?’ I demanded.

‘I’ve lost it,’ she said.

I grabbed her shoulder bag and rummaged inside … God, the junk in there, something from every hotel of every tour, packets of soap and shampoo (never to be used), stationery, an ashtray … but no letter.

‘You see, I’m telling the truth,’ she said. ‘I’ve lost it … so you can believe me when I tell you it’s not worth reading.’

It was always the same old junkie meta-logic. Any nonsense could be justified, any absurdity rationalised.

Demetrius had also had enough, retreating to Manchester to recuperate. He had to find another road manager in his stead, someone dependable and unbreakable. Raincoat pleaded for the job, but after the poisoning attempt Raincoat’s days were numbered. Besides, Raincoat was doing a new Frankie impersonation – the Man With the Golden Arm – for real. Raincoat had joined up with the Undead and was now plying his mission on the street. Demetrius felt there was no alternative but to bring in a character he’d threatened us with before – the Big Grief.

We-e-e-ll … ’ere we are

’n ’ere we go ’n geddawayeeay

… Rockin’ all over the world.

‘C’mon, let’s fookin’ ’ear yer! Sing up! That means you, snog-gin’ each other in the back … Now, are yer right, Nico? ’Ave yer got yer words sorted, luv? Sound. Right, I’ll count ter four an’ then all tergether …’

Grief was the last in a long line of missing links, Cro-Magnon throwbacks from Eccles. Demetrius had pulled him in to control us and to punish us. Eccles is a social anthropologist’s paradise, the sinkhole of Manchester, where the indigenous troglodytic inhabitants have squatted round campfires, roasting carcasses and molesting each other’s wives for millennia. Now their caves all have satellite dishes but their table manners remain the same. Grief was indigenous Eccles. Hair a long frizzy helmet, huge canine teeth and an expression of permanent rabid rage. He’d learned his craft down the Stretford End, cracking skulls, throwing (and catching) Irish grenades, potatoes with razorblades stuck in their sides. Grief was playtime dread, everything you ever feared back in the schoolyard.

‘Right! One more time! … Just listen ter Nico – singin’ ’er ’eart out, arntyer luv? An’ they lost the fookin’ war! So, come on, loud an’ clear … ‘Rockin’ All Over the World’ one more time!’