As you head into Tokyo from Narita Airport, you become immediately aware of Tokyo heading towards you. The ever-expanding ingenuity of the city ensures that its dreams are kept within easy reach. On the left, King Ludwig of Bavaria’s castle replicated in superstone and plexiglass for Disneyworld; Love Hotels, fantasy sex palaces with heart-shaped jacuzzis and’64 Cadillac Coupe de Ville-shaped beds. Pinkku. The ultimate, coveted, erotic dream icon for the Japanese male is the delicate pink underflesh of a virgin’s inner labia. Pinkku. For the Japanese as a whole, the precise moment of the highest erotic arousal occurs at the second before loss of innocence. Love Hotels help to maintain that highly-charged adolescent atmosphere … besides, domestic accommodation is frequently so cramped that couples are often obliged to conduct their entire sex lives in such places.

The traffic slowed to a near-stop. Beyond the Love Hotels and the cathedrals of kitsch was the dirty Sea of Japan, fizzing with a constant rain. Yuki, our interpreter, apologised for the traffic congestion. A truck had gone off the road and smashed into the lane barrier. As we passed we could see directly into the cabin – the driver slumped dead in his seatbelt, the rain beating down on his steaming truck.

The Ropongi Prince Hotel is built like a Pavlova cake with, as its featured centre, a glass-sided heated pool. It cost £20 a splash. There were no takers. We had a pre-tour conference with the management team to discuss the stage set-up, sound, lighting and so on. Nico was tired and absented herself but Cale, always concerned with the minutiae of performance, was as punctual as ever. I hadn’t seen him much in the past couple of years and I was surprised at the transformation. Indeed the new slimline, calorie-controlled, alcohol-free, no chemical additives, one hundred per cent pure Caleness came as something of a shock to us all. He just didn’t seem like the flatulent Druid we’d known from before, who drank champagne from a pint mug. He must have lost four stone at least, and looked ten years younger and fitter. His hair was dyed a very fetching purple/ black and cut in a Rosa Klebb crop. He exuded health – and wealth. Did I want to come and look at some clothes at Issey Miyake’s? No thanks. I had about £10 in my pocket, and until after the first show it was staying there. Did I want to go for a wander round the Shibuya stores? No.

The cherry trees were in blossom and the promoters suggested we go and sit under ‘the chelly brossom’ for good luck.

We went for a walk in Yoyogi Park – Nico, Cale, me, Dids, Grief and a young guitar-player called Henry. Henry was very keen, very capable – but totally inexperienced in the ways of Nico. He was never quite sure which image to adopt. He had on a pair of Chinese slippers, camouflage trousers, black polo neck, green leather Gestapo coat, blue eyeliner and a Nero haircut topped with a black beret, circa 1958 Left Bank Paris. His broken nose gave him an air of toughness that was undermined by a public schoolboy nervousness. Girls were a source of inner panic and perplexity to Henry. He’d blush if introduced to one. Grief suggested a trip to a No-Panties bar, where the floors are mirrored. Henry reflected but didn’t understand. When Grief explained, Henry was horrified. He was a vegetarian.

Every Sunday at Yoyogi Park there’s an amateur talent show. Down a long avenue there are groups lined up, all playing at once. It’s a living Rock ’n’ Roll Museum. There must have been a dozen Elvises and five or six Beatles, even three diminutive, slightly tubby girls miming to the Supremes. The further down the avenue we went the more esoteric the acts became, until we got to the Japanese Velvet Underground.

A wa kassu sha da po ga weh

To ar tomaros patees?

Though Cale looked a lot younger and more closely resembled the man of his Velvet Underground days, he was concealed beneath a large beaver fur hat and a cashmere overcoat; and Nico was hardly her old physical self. The Velveteens didn’t recognise their role-models staring them in the face.

Nico and Cale were not getting on well. He objected to her smoking in his presence. Then there were problems about the shows; Nico wanted to go on last; ‘This John Cale – who does he think he is? I’m a star too.’ But Cale was top of the bill. Though he’d been booked to play with a group he’d turned up on his own at the end of a long solo tour. The Japanese were politely astonished at such a blatant breach of contract.

His act was so sharp and synchronised that he didn’t want the stage cluttered up with Dids’s old car parts and he insisted on the piano being tuned after I’d used it. Nevertheless his contract stipulated a group, so he had the idea that Dids, Henry and I should round off the evening with him doing a karaoke medley of Velvet Underground hits.

‘I’m not exactly au fait with the Velvet Underground material,’ said Henry. ‘What do you think I should do?’

‘Just turn your amp up to ten,’ I said, ‘and look like you don’t care.’

Nico didn’t like the idea of us playing with Cale, it made her feel more marginal, more of a warm-up act. So on the way to every show there were rows about who was doing what, and the order of appearance, and the fact that Cale absolutely refused to perform a number with Nico.

‘Oh go on,’ I said. ‘It’d be like Sonny and Cher getting back together again.’

Cale always sat in the front passenger seat, the Demetrius seat, taking in every inch of the city space. ‘This is the future,’ he’d say, pointing out a feature of some building none of us could see because his hat blocked the view.

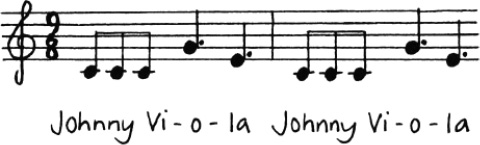

‘Johnny Vi-o-la! Johnny Vi-o-la!’

Cale ignored her. Nico sat behind him, pointing and snickering at the beaver hat and rubbing her fingers together to suggest Cale’s moneyed status.

It took on a singing, chant-like quality. ‘So fashionable now, so chic … such a transformaaation.’ She whispered in my ear, ‘But still a schmuck,’ and enshrouded him in a cloud of Marlboro smoke.

Typically, we were inadequately rehearsed, our raggedness emphasised by Cale’s streamlined performance. Dids was deep into his hubcap metal-bashing. You’d hear a conventional drum pattern, then suddenly there’d come this clanking of ghostly chains that threw the rest of us completely. Dids would peer out crossly at us from behind a canopy of broken cymbals and twisted metal, shaking his head and admonishing us before the assembled audience.

Cale, by contrast, sprang on to the stage and straight into his repertoire, barely pausing between songs. You’d hear him in his dressing-room, practising right up to the last minute some tricky little guitar figure. Alone with his piano or a simple guitar accompaniment, he personified total confidence and mastery of his material. He seemed to have got his act under control at last – the bellicose self-indulgence burnt out earlier in the day on the squash court.

As the tour progressed Cale distanced himself further and further from the drifting derelicts of his past. Every day he’d work out on the squash court: super-concentrated, super-confident, for the evening’s work ahead.

We took the bullet train to Osaka. Cale refused to sit with Nico and me. He thought smokers should wear plague bells. I had alcohol poisoning from a misguided attempt to outdrink Grief in a sake bar the night before. Cale was delighted, it meant he could crow, as the freshly converted do, about the merits of clean living.

At the evening meal he enthused about the sushi. ‘Mmmm – this raw dolphin is re-a-lly de-e-licious … want a slice, James?’

(At an earlier gastronomic encounter the waitress brought a bowl of clear broth to the table, then added a few vegetables and some prawns. We assumed the prawns were dead, but one of them leapt out of the boiling liquid. The waitress held it under with a pair of chopsticks. Nico fled outside to throw up.)

After the Osaka show an angel stood outside Cale’s dressing-room, clutching an exquisitely wrapped parcel. Cale was her personal god. But, like a lot of gods, he was hard to get in touch with, and had insisted on a dressing-room at the opposite end of the corridor from Nico and her etceteras. He did not wish to be distracted from his purity of purpose by anyone. I recalled Raincoat’s dictum of yesteryear, ‘It’s only pop.’ On behalf of our Nico-tine-stained retinue I demanded admittance.

‘The girl’s been waiting all her life,’ I explained. ‘She’s got type-outs of all your lyrics. She’s more than a fan, she’s a true believer.’ I gained an audience for the trembling disciple.

The girl is shy, word-panicked, mute. Her eyes glance briefly at the face of the slimmed-down bard of the three-minute-forty-second psychodrama, then down to the floor again in sonkei (respect). She has a specially-prepared speech she’d like to make, if possible.

‘Yes, yes, yes. Get on with it,’ says Cale.

The girl reads from her notes: ‘John Cale. I thank you for your beautiful music. Please accept this gift in sincere appreciation of your gift.’

Once more her gaze tentatively touches the image of the performer-priest-king, before being lowered again in veneration.

Cale takes the parcel, snatches at the butterfly-ribboned bow and tears open the lovingly-wrapped package. Inside the silk-lined box is a porcelain presentation bottle of vintage sake, in the shape of a Kabuki demon mask. Fierce red eyes, diabolical black beard, death-white skin. Grotesquely beautiful and stunningly expensive.

‘I don’t drink,’ says Cale, and hands the flask of demon alcohol back to her.

The girl puts her humble offering for the god down on the altar of his guitar-case and leaves in tears.

Osaka star dressing-room

Girl cries

Cherry blossom falls.

Hotel Osaka Grand

Late afternoon. Upper-class schoolgirls, thoroughbred daughters of Mr Sony and Mr Mitsubishi cycling across the bridge in dark navy sailor tops, long pleated skirts and smog-masks.

At night you enter a forest of neon, there are no addresses and no sensible way of finding anywhere, even the neon is transient. Architecture as advertising space.

Cale: ‘When you’re playing Northern California they come up to you out of the past and say, “Remember that blowjob I gave you in’Frisco in’67?” What are you supposed to say? What do they want?’

On the TV there are constant newsflashes about a teenage pop-star’s suicide. Close-ups of the Tokyo hotel window she jumped from and the bloodstained ground she pulped on. She’d been dropped by her record company on her seventeenth birthday, because she was seventeen. So she dropped herself. The boys back in Artist & Repertoire want the quintessence of adolescence, 13–16, after that the Pinkku’s all used up.

Back at the Ropongi Prince in Tokyo the pool just steamed, all by itself, lifeless and empty. Cale wouldn’t because he was too tight, and Nico couldn’t because she didn’t swim. Then a bunch of guys arrived from George Michael’s true faith world tour – they were all wearing identical leather flying jackets, emblazoned with George the Greek’s tour logo. G.M. himself was staying at the Tokyo Hilton, away from prying paparazzi, in his own private floating world of geisha satori. Soon his minions were splashing about in the pool. ‘More health freaks,’ said Nico.

Crowds are different in Japan, they’re more self-controlled. Coming out of the Shibuya subway the traffic stops for the crowds to cross the square from all sides, in perfect black and white symmetry, like an Op Art kaleidoscope. Then it’s the traffic’s turn. While you’re waiting to cross, high above the square a giant video advertising screen, the size of a tennis court, sells you pieces of techno heaven. There’s no such thing as dead time in Tokyo. As you walk up the hill towards Parco, the crowds don’t saunter untidily as in the West, but seem organised by a hidden common purpose. No one touches, but all are linked by an invisible thread of meaning. Roundeyes walks alone.

The last show was in the Seibu Theatre in the Parco store complex. Somewhat akin to having the Wigmore Hall in the middle of Harrods. The Japanese are a little more honest about these matters than we are and see no contradiction between art and commerce.

Cale complained that we had to share a dressing-room. Immediately a no-smoking zone came into being. The shows were early and he wanted to go on first in order to do some last-minute shopping.

Dids, Henry and I did the Velvet Underground stuff with him, came off, and then went on again to do Nico’s set. Our reappearance took the wind out of Nico’s sails and the polite, but lifeless, applause at the end left her despondent. Compared with her last tour of Japan, which had been successful both in audience rapport and in financial terms, this was a half-hearted affair. They’d seen Nico the year before, but this was Cale’s first trip to Japan and so there was more of a novelty value attached to his appearances. Novelty is intrinsic to success in Japan.

‘Famous not popular,’ was the verdict on Nico from Mr Hidaka, Yuki’s boss.

As for Cale, Yuki advised us to come to some financial agreement with him, as he’d been paid for a group and we’d accompanied him on every show.

‘Let’s have a breakfast meeting and discuss it then,’ said Cale, hurrying off to thread up at Yamamoto.

I booked an alarm call for 9.00 a.m. and made it to the coffee and bun for the first time in a while. Henry and Dids were waiting, scowling.

‘Am I late?’ I asked.

‘Ow yez. You might as well ’ave stayed in bayed,’ said Dids. ‘Cant’s done a runner!’

‘Yes,’ said Henry, ‘I think it’s jolly bad form.’

Cale had taken the six-o’clock morning flight out, to the surprise of the fastidiously polite, quietly furious promoters. Yuki was astonished at such peremptory rudeness.

On the way to Narita Airport Nico rummaged inside her bag.

‘Look! John left me a present … and I thought he hated me.’

She opened the parcel. Why, it was a presentation bottle of vintage sake in the shape of a Kabuki demon mask.

‘Jesus …’ She recoiled in disgust. ‘It’s horrible.’

She passed the bad magic on to Grief, who drank the lot down.

‘I’m never sharing a bill with that aaasshole again!’

*

Wrong. Three weeks later she had to share a double bill with the tightest coracle in Rock’n’roll at the Palais des Beaux Arts, Brussels. The show had been booked by Demetrius.

Demetrius had turned up with the whole of Didsbury, in the shape of Eric Random and his Bedlamites, who thought they were the star turn. Nico, Dids, Henry and I had flown in earlier.

‘I’ve brought along my fellow free spirits who wish to share the camaraderie of the open road.’ Demetrius was in a semi-ecstatic state.

He’d just come out of hospital after two months’ incapacitation due to a broken leg. He’d jumped off a garage roof. No one knew exactly why he’d climbed up there in the first place. There was talk that his unrequited love for Nico had finally driven him over the edge. There was also the suggestion that the good Doctor had become involved in certain curious nocturnal practices. His demeanour was certainly different. He now walked with a limp and carried a stick, which he jabbed at the ground to underline his pronouncements.

‘I have knelt before the shining gates of Heaven, and I have crawled beneath the gaping jaws of Hell … and believe me, James, though, in truth, we live upon a dungheap covered in flies, I draw comfort from the close consolation of the human reek.’

Everyone wanted to play, but Dr Demetrius’s circus of free spirits wouldn’t fit on to the stage. Random was sulking and combing his hair furiously. He’d missed out on Japan, having been there the first time round. In Tokyo were his chosen handmaidens, awaiting their annual dose of Tantric Love Juice.

Cale had checked himself into a separate hotel and had ensured that he was given a private dressing-room in another part of the theatre building. ‘He thinks he’s Von Karajan,’ said Nico. ‘More cheese sandwiches for us,’ said Demetrius.

Nico and I did a version of ‘My Funny Valentine’ which, apart from that time in the Signora’s basement, was probably the best we could ever do with that song. We just emptied it out into a bare piano waltz for the emotionally crippled.

Amazingly, Cale allowed Nico to duet with him on one of his songs, a setting of Dylan Thomas’s A Child’s Christmas in Wales. Nico fluffed her lines halfway through, blushed and went shy, but he prompted and carried her to the end, bringing the show to a rapturous close. Later he did his usual disappearing trick and vanished to his hotel the moment he was paid.

Back at our hotel in the Place Roger, Random and I noticed a furtive Dr Demetrius hobbling off down the street. At that time of night, and in the teeming rain, he could only be up to one thing. We followed him. Round the block was a whole street of bordellos. Demetrius was window shopping. He stopped outside one, peered momentarily inside to check the merchandise, then pressed the bell. A few minutes later Random and I followed his example and slipped discreetly into the red velvet night.