RULE NINE

Remember That Misinformation Can Be Beautiful, Too

We are in danger of making the same statistical mistakes that we’ve always made—only prettier.

• Michael Blastland, co-creator of BBC Radio 4’s More or Less

Florence Nightingale would have needed no introduction in Victorian Britain: she was the nation’s unofficial patron saint, and was the only nonroyal woman to appear on English banknotes until 2002. Her legend continues to this day; the 4,000-bed London hospital constructed in a few days to meet the demands of the pandemic was named Nightingale Hospital.

In Florence Nightingale’s own time, the only woman more recognizable would have been Queen Victoria herself. The nation revered Nightingale for her “feminine” heroics in the Crimean War, pacing the wards of the Scutari barracks hospital in Istanbul. Here’s an editorial in The Times from February 8, 1855: “She is a ministering angel without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her.”

Bleurgh. I’m much more interested in her contribution as a statistician.

Nightingale was the first woman to be made a fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. When her “slender form” wasn’t too busy gliding along the corridors, causing faces to “soften with gratitude,” she was spending her time in Scutari carefully compiling data about disease and death. What she saw in the figures inspired her with a mission to change both the British Army and the British nation. Shortly after her return from Crimea, at one of the intellectual dinner parties she often attended, she met William Farr. Farr, thirteen years her senior, had been born to poor parents and lacked Nightingale’s fame, front-line experience, and political connections. But he was the best statistician in the country, and that was what mattered to her. They became friends and collaborators. One of Nightingale’s many biographers, Hugh Small, convincingly argues that the skillful way in which she and Farr wielded the data she’d assembled ended up raising life expectancy in the UK by twenty years and saving millions of lives.1

There’s a famous remark in a letter between Nightingale and Farr, written in the spring of 1861: “You complain that your report would be dry. The dryer the better. Statistics should be the dryest of all reading.” It is reported by several biographers as being written by Farr to Nightingale. That makes sense—the fusty middle-aged statistician advising the fiery young advocate to rein in her righteous campaigning impulses. In fact, the biographers are wrong. The letter was written by Nightingale to Farr.* The pair of them were wrestling with the problem of how best to communicate with statistics, and Nightingale was affirming that communications had to be based on hard, dry facts. (In the same letter she wrote: “We want facts. ‘Facta, facta facta’ is the motto which ought to stand at the head of all statistical work.”2)

But that didn’t mean the communications themselves had to be dry. Nightingale could conjure up an arresting turn of phrase—she argued, for example, that the needlessly high death rate in the army in peacetime was the equivalent of taking 1,100 men out onto Salisbury Plain and shooting them.

More pertinent for our purposes, she designed an image that was a landmark in data visualization. Her “rose diagram” was one of the first-ever infographics. That makes her perhaps the first person to grasp that busy, influential people would pay far more attention to a vivid diagram than to a table of numbers. In one letter, written on Christmas Day 1857—less than three years after being beatified in The Times—she sketched out a plan to use data visualization for social change. She declared her plan to have her diagrams glazed, framed, and hung on the wall at the Army Medical Board, Horse Guards, and War Department. “This is what they do not know and did ought to!” she wrote. She even planned to lobby Queen Victoria, and she knew all too well that beautiful diagrams would be essential. As Nightingale quipped when sending one of her analytical books to the Queen, “She may look at it because it has pictures.”3

It’s a cynical, almost contemptuous, thing to write. But it is true. A chart has a special power. Our visual sense is potent, perhaps too potent. The word “see” is often used as a direct synonym for “understand”—“I see what you mean.” Yet sometimes we see but we don’t understand; worse, we see, then “understand” something that isn’t true at all. Done well, a picture of data is worth the proverbial thousand words. It is more than persuasive; it shows us things we could not have seen before, revealing patterns amid chaos. However, much depends on the intent of the chart’s creator, and the wisdom of the reader.

This chapter, then, will talk about what happens when we try to turn numbers into pictures. We’ll see what can go wrong. And by following the story behind Nightingale’s famous rose diagram, we’ll see how powerful data visualization can be when used clearly and honestly.

Much of the data visualization that bombards us today is decoration at best, and distraction or even disinformation at worst. The decorative function is surprisingly common, perhaps because the data visualization teams of many media organizations are part of the art departments. They are led by people whose skills and experience are not in statistics but in illustration or graphic design.4 The emphasis is on the visualization, not on the data. It is, above all, a picture.

The most egregious examples of numbers as decoration are nothing more than the same old number in a large, striking font.

19

the number of words in the preceding sentence

I suppose this brightens up a page loaded with text, but it’s hardly an insightful use of ink. Also, the correct number is twenty-one. Never let zippy design distract you from the possibility that the underlying numbers simply might be wrong.

Another decorative approach is what we might call “Big Duck” graphics.5 The Big Duck itself is a building near New York City, built by a duck farmer in the 1930s to serve as a shop from which he could sell duck eggs and ducks. It may not entirely surprise you to read that the Big Duck closely resembles a thirty-foot-long white duck. The architects Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi used the term “ducks” to describe any building that is designed to resemble a relevant product or service, such as a strawberry stand in the shape of a giant strawberry, or Shenzhen airport, which has the shape of an airplane.

The graphic guru Edward Tufte borrowed the “duck” term to describe a similar tendency in graphics: a graph about the NASA budget in the shape of a rocket; a graph about higher education in the shape of a mortarboard; or, in the example created for Time by Nigel Holmes, a graph about the price of diamonds in the shape of a diamond-adorned dame, her shapely fishnet-clad legs sketching out the price of a flawless 1-carat stone. Sometimes these visual puns do help people to read and remember the information they frame.6 But they are often a poor attempt at humor, or a desperate bid to inject interest into data that seem dull. Data visualization ducks can be more than tasteless: the duckness of the graph can actually obscure—or worse, it can misrepresent—the underlying information.*

There is a curious historical parallel for this: dazzle camouflage. Dazzle was a defense mechanism for battleships in the First World War, always at risk of being torpedoed by a lurking submarine. The usual “blending in” method of camouflage wasn’t an option for a huge steel vessel that advertised its presence against an ever-changing sea and sky with bow waves and smokestacks. Dazzle camouflage flipped the idea of camouflage on its head. It was an abstract riot of squiggles and harlequin patterns—in fact, it bore enough of a resemblance to Cubist art that Picasso himself impishly tried to claim the credit.7

The real inventor of dazzle was Norman Wilkinson, a charismatic artist who joined the Royal Naval Reserve at the beginning of the war. He later explained, “Since it was impossible to paint a ship so that she could not be seen by a submarine, the extreme opposite was the answer—in other words, to paint her, not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as the course on which she was heading.”

Because torpedoes took some time to slice through the water to hit their target, the submarine’s periscope operator had swiftly to judge a ship’s speed and direction before firing the torpedo on an intercept course. Gazing through a tiny scope at a ship in dazzle camouflage, the operator knew he was looking at a ship, but would find it hard to make out any of the clues that mattered for aiming the torpedo accurately. The squiggles looked like bow waves, while harlequin diamonds could easily be confused with the various angled surfaces of a battleship’s hull. The result was that the lookout could easily misjudge the ship’s speed, the angle of its travel, and the size of and therefore distance to the ship. He might even see two ships rather than one, or mistake the bow for the stern and aim behind the ship rather than ahead of it. Dazzle camouflage was intended to provoke misjudgments.

More than a century later, it isn’t hard to see echoes of dazzle camouflage in infographics. From TV to newspapers, websites to social media, we are surrounded by graphical images that grab our attention, pleading to be shared and retweeted, but that also—intentionally or not—mislead, prodding us to a judgment that is often mistaken. At least the periscope operator whose eye was caught by a dazzle ship would have realized that he was looking at something odd, even if he couldn’t make sense of it. But many of us who are dazzled by infographics don’t suspect a thing.

All that lay far in the future when Florence Nightingale was a girl discovering a passion for data. At the age of nine she was categorizing and graphing the plants in her garden. As she grew older, she successfully pleaded with her parents to receive high-quality mathematical tuition; at dinner parties she met the likes of Charles Babbage, a mathematician and designer of a now-famous proto-computer; she was a houseguest of Ada Lovelace, Babbage’s collaborator; and she corresponded with the great Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet. Quetelet was the person who popularized the idea of taking the “average” or “arithmetic mean” of a group, which was a revolutionary way to summarize complex data with a single number. He also pioneered the idea that statistics could be used to analyze not just astronomical observations or the behavior of gases, but social, psychological, and medical questions such as the prevalence of suicide, obesity, or crime. Babbage and Quetelet were later to be founders of the Royal Statistical Society; Nightingale, as I have mentioned, became its first female fellow.

By her thirties, Florence Nightingale was steeped in this world of pioneering mathematicians—but her job was as nursing superintendent at a small hospital in London’s Harley Street, where she not only sorted out the bookkeeping and hospital infrastructure, but sent surveys to other hospitals all around Europe, asking them about their administrative practices and tabulating the results.

It was at this time, late in 1854, that she was persuaded by the secretary of state for war, her old friend Sidney Herbert, to lead a delegation of nurses to Istanbul to tend to wounded British soldiers from the Crimean War. The war was a bitter struggle between the Russian Empire and several other great European powers, including Britain. Nightingale’s presence with the British Army, which was unprecedented for a woman, was designed to pacify a public incensed by what they were reading about the dreadful conditions in the hospitals there. Reports in The Times turned the Crimean War into a long-running narrative of disaster with many familiar characters. By the end of it all, Florence Nightingale was perhaps the only figure to retain public support; the generals and the rest had been discredited by the catastrophe.

The Barrack Hospital in Scutari, Istanbul, was a death trap. Hundreds of soldiers from the Crimean front were succumbing to typhus, cholera, and dysentery as they tried to recover from their wounds in cramped conditions next to the sewers. Nightingale arrived to find rats and fleas everywhere she looked. Basics such as beds and blankets were missing, as were food to cook, pots to cook it in, and bowls to eat it from. All this outraged public opinion when it was reported in The Times, and Nightingale herself was quick to use the newspaper to raise funds from readers—and to pressure an ill-organized British Army to get its act together.

Less of a cause célèbre was that the hospital record-keeping was as badly organized as anything else. There were no standardized medical records and no consistent reporting between the various British Army hospitals. This may seem a relatively trivial matter, but Nightingale knew it was a big problem. Without good statistics it was impossible to understand why so many soldiers were dying, or to find a way to improve conditions. Even the dead were going uncounted, buried without their deaths being recorded. Nightingale saw all this more closely than anyone. She even took on the duty of writing to the family of each dead soldier. But she wanted the bird’s-eye view as well as personal experience, understanding that certain truths can only be perceived through the statistical lens. She tried to standardize and make sense of the hospital data.

Long after the war was over, Nightingale was still pressing to improve the standard of medical statistics. Some of this work, in partnership with Farr, was magnificently unglamorous. For example, they tried to standardize the description of different illnesses and causes of death, with Farr leading on the technical side while Nightingale campaigned for his ideas to be adopted. She wrote to the International Statistical Congress in 1860 to argue that hospitals should make use of Farr’s methods by collecting statistics according to a uniform standard. This wasn’t mere fussiness: standardizing the statistics meant that different hospitals could be compared and could learn from each other. It is this sort of statistical foundation-building that many of us overlook—but as we’ve seen many times in this book, without well-defined standards for statistical record-keeping, nothing adds up. Numbers can easily confuse us when they are unmoored from a clear definition.

Florence Nightingale may have been a savvy campaigner, but her campaigns were built on the most solid of foundations.

The most straightforward problem with a clever decorative idea is that the basic data may not be solid. The visualization then simply hides that fact—the shimmering icing over a moldering statistical cake.

One educational example is Debtris, an unforgettable animation produced several years ago by David McCandless, author of Information Is Beautiful.8 It shows large blocks falling slowly against an eight-bit soundtrack in homage to the addictive computer game Tetris. Their size indicates their dollar value; “$60bn: estimated cost of Iraq war in 2003” is followed by “$3000bn: estimated total cost of Iraq war,” and then Walmart’s revenue, the United Nations’ budget, the cost of the financial crisis, and much else. As decoration this is wonderful stuff: the graph looks great, the music endlessly loops in your head, and the slow revealing of the different comparisons leaves you gasping with surprise, laughter, and anger.

But the same elements that make Debtris such a delight to watch also make it much harder to spot the underlying problems. Statistical apples are compared with statistical oranges throughout. Stocks are compared with flows. That’s the equivalent of comparing the total cost of buying a house with the annual cost of renting one; it’s not a trivial confusion. Net measures are put alongside gross ones—the equivalent of comparing a firm’s profit with its turnover.

The shocking difference between the before-and-after comparisons of the cost of the war in Iraq turns out to be based on an unfair comparison. (Admittedly, a fair comparison might also show a shocking difference.) The prewar number is a narrow estimate: the cost to the US military budget. The postwar number is very broad, including a figure for the cost of lost life, the cost of high oil prices, and a huge sum for the cost of macroeconomic instability, putting part of the blame for the 2008 financial crisis on the war. That broad estimate of cost is not unreasonable, but what is unreasonable is to put it alongside a very different kind of estimate without comment. What seems to be a pure before-and-after contrast is actually narrow-and-before versus broad-and-after, measuring a different thing at a different time. Nobody looking at the Debtris animation would realize that.

Debtris was published in 2010, and quickly became my favorite cautionary example—the visualization is so good but the data are so bad. A couple of years later I was introduced to David McCandless at a conference. I felt a bit awkward. I’d been moaning about his work while he wasn’t in the room, but I’d never done him the courtesy of sending him an email with my comments. But perhaps he hadn’t noticed them? I felt compelled to confess.

“I should probably say, David, that I have a concern about your Debtris animation.”

“I know you do,” he replied.

I squirmed. But to his credit, his more recent work is similarly striking, while also being more careful about the underlying data. For example, a visualization in a similar spirit—“The Billion Pound-O-Gram”—still mixes stocks and flows, but it is much more transparent about doing so.9 Further to McCandless’s defense, the only reason I could find out that the data behind his Debtris animation were patchy and inconsistent is that he fully referenced it. Many don’t.

So information is beautiful—but misinformation can be beautiful, too. And producing beautiful misinformation is becoming easier than ever.

Graphics once required a great deal of time and trouble to produce and then reproduce. Even something as simple as a graphic with straight lines, precise edges, and color would have demanded expert draftsmanship and expensive printing methods. It’s telling that Edward Tufte, in a 1983 book, devotes some attention to deploring the use of diagonally shaded black-and-white patterns because they can produce an unsettling optional illusion of a flicker. “This moiré vibration [is] probably the most common form of graphical clutter,” he complains. It may have been common then; it is unheard of today. We would now invariably use color rather than diagonal shading.

No draftsmanship is required these days. A variety of powerful software tools can swiftly turn numbers into pictures. But any powerful tool should be used with care, and the very speed of the process means that impressive-seeming graphics can be created without any serious thought about the underlying data or how best to describe them.

The ease of creating pretty graphics is exceeded only by the ease of sharing them. A quick “like” on Facebook or a retweet on Twitter will speed the image on. Ideas that are best expressed in words or numbers are turned into graphics anyway, because that’s what spreads on social media. Unfortunately, the selection mechanism is often some combination of beauty and shock value, rather than pertinence and accuracy.

Consider the experience of Brian Brettschneider, a climate scientist with a fondness for gorgeous maps. He celebrated Thanksgiving in 2018 by producing a map showing “the favorite Thanksgiving Day pie by region,” including coconut cream pie for the Midwest, sweet potato pie for the West Coast, and key lime pie for the South. As a Brit, I don’t know much about Thanksgiving, and my favorite pie is a cold pork pie, but I’m told that the map seemed wrong to American eyes. No pumpkin pie? No apple pie? The map—and the outrage—went viral on Twitter. Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, a prominent Republican politician, didn’t like the suggestion that Texans favored key lime pie: “#FakeNews,” he tweeted.

And he was right. Brettschneider had made it all up. He was joking; the map was a parody of all the other bad maps that go viral on the internet. After more than a million people had seen the tweet, however, Brettschneider started to become uneasy. Did people even know he was joking? We don’t know who got the joke, who shared the map in mild outrage, and who believed it was solid fact. But we can be fairly sure that the use of a vivid graphic gave it its viral power. “We tend to place very high value in maps as holders of accurate information,” writes Brettschneider. “If it’s in a map, it must be true, right? If I had tweeted a joke list of favorite pies by region, it would be very quickly ignored. Since it was in map form, it had an air of authenticity.”10

Quite so. My only difference with Brettschneider is that I don’t think the problem is limited to maps. Any vivid graphic has the potential to go viral, whether true, false, or a bit of both. This book started with a warning that we should notice our emotional response to the factual claims around us. Just so: pictures engage the imagination and the emotion, and are easily shared before we have time to think a little harder. If we don’t, we’re allowing ourselves to be dazzled.

The situation in the Scutari hospital was catastrophic. Florence Nightingale was later to write, “To inexperienced eyes the Scutari buildings were magnificent. To ours, in their first state, they were truly whited sepulchers, pest houses.”11 But why, exactly, were so many soldiers dying?

Poor hygiene is the obvious explanation from a modern perspective: germs were being transmitted freely in the filthy, vermin-ridden conditions. But the idea that diseases might be transmitted by microbes, and fought by using antiseptics and keeping things clean, was in its infancy. Very few doctors would even have heard of it as speculation, let alone believed it. Nightingale was no different; she thought instead that the high death toll in Scutari was due to lack of food and supplies, a problem she sought to remedy with her high-profile fundraising and campaigning through The Times.

Nevertheless, she also requested a team to help clean up the hospital, and in the spring of 1855 this “sanitary commission” arrived from the UK, whitewashed the walls, carted away filth and dead animals, and flushed out the sewers. The main hope was to make the hospital less unpleasant, but the immediate effect was to cut the death rate almost immediately from more than 50 percent to 20 percent.

Florence Nightingale wanted to understand what had happened, and why. And like Richard Doll and Austin Bradford Hill, she believed she could work out the truth if she examined the data with sufficient care. Her scrupulous record-keeping made the dramatic improvement after the sanitary commission’s work very clear indeed.

When Nightingale returned from the war, Queen Victoria summoned her for a royal audience. Nightingale persuaded Victoria to support a royal commission investigating the health of the army. She also recommended that the commission include William Farr, though Farr’s lowborn status meant that he was not treated well by the establishment; he was eventually retained only as an unpaid consultant to the commission.

Nightingale and Farr concluded that poor sanitation had caused many of the deaths in the Crimean War hospitals, and that most military and medical professionals had failed to learn this lesson. The problem was much bigger than one war: it was an ongoing public health disaster in barracks, civilian hospitals, and beyond. The pair began to campaign for better public health measures, tighter laws on hygiene in rented properties, and improvements to sanitation in barracks and hospitals across the country.*

Nightingale may have been the most famous nurse in the country, but she was a woman in a man’s world, and had to convince the country’s medical and military establishments, led by England’s chief medical officer, John Simon, that they had been doing things wrong all their lives. Dr. Simon wrote in 1858 that deaths from contagious diseases were “practically speaking, unavoidable”—that there was nothing to be done to prevent future deaths. Nightingale set herself the task of proving him wrong.

William Farr’s daughter, Mary, described eavesdropping on an early conversation between her father and Florence Nightingale. Mary recalled Farr giving Nightingale a warning about speaking out against the establishment. “‘Well, if you do it, you will make yourself enemies,’ and she drew herself up and answered, ‘After what I’ve seen, I can fire my own guns.’”12

Nightingale wrote to her friend the secretary of state for war Sidney Herbert, “Whenever I am infuriated, I revenge myself with a new diagram.”13 Statistics had been the telescope through which she perceived the truth; now she needed a diagram that would compel everyone else to look at the truth, too.

A good chart isn’t an illustration but a visual argument,” declares Alberto Cairo near the beginning of his book How Charts Lie.14 As the title of the book implies, Cairo has some concerns. If a good chart is a visual argument, a bad chart may be a confusing mess—or it may also be a visual argument, but a deceptive and seductive one. Either way, by organizing and presenting the data, we are inviting people to draw certain conclusions. And just as a verbal argument can be logical or emotional, sharp or woolly, clear or baffling, honest or misleading, so too can the argument made by a chart.

I should note here that not all good charts are visual arguments. Some data visualization is not intended to be persuasive, but exploratory. If you’re handling a complex dataset, you’ll learn a lot by turning it into a few different graphs to see what they show. Trends and patterns will often leap out immediately if plotted in the right way. For example, visualization expert Robert Kosara suggests plotting linear data on a spiral. If there’s a periodic pattern to the data—say, repeating every seven days or every three months—that may be concealed by other fluctuations in a conventional plot but will leap out in a spiral plot.

Similarly, certain kinds of problems make themselves known immediately when the data are turned into pictures. Imagine a dataset with the height and weight of tens of thousands of hospital patients. Some of them are fifty or sixty feet tall! That must be a typo. Hundreds of them have a weight of zero. That would be because a nurse or doctor was filling in an electronic form, didn’t take a weight measurement, so just hit “enter” and moved on to the next box. These problems won’t be apparent if you ask your computer to calculate an average or a standard deviation, or if you scan columns of data manually. If you look at a picture of the data, however, you’ll see the problem in a second.

But let’s assume you’ve explored your numbers, and now you want to turn them into a visual argument. The standard advice for management consultants and academic researchers presenting a graph is to include a title or caption that calls attention to the key features of the data and draws a conclusion.15

Say It with Charts, the bible of management consultants, makes this process very clear. First, says author Gene Zelazny, decide what you want to say with a graph. Once you’ve decided what you want to say, that suggests a particular kind of comparison. That, in turn, suggests a particular choice of graph—such as a scatterplot, a line graph, a stacked bar chart, or a pie chart.* Finally, underline your message by sticking it in the graph title. Don’t just write “Number of contracts, January–August.” Write something like “The number of contracts has increased” or “The number of contracts has been fluctuating,” depending on whether you’d like to call attention to the upward trend or to the variations around that trend. Zelazny’s vision is one in which the management consultant tells people what to think. Both the graphs and the annotation are chosen to support that message.

I realize there’s something unsettling about the way this process starts with the conclusion and then figures out how to package the data to support that conclusion. But let’s be fair: a lot of communication works in this way. Newspaper articles begin with a headline; the rest of the text is explanation. Even a scientific paper begins with an abstract that serves a similar purpose to a newspaper headline: it tells you what happened and what it means. A good journalist doesn’t begin reporting with the conclusion in mind; a good scientist doesn’t decide on the results before the experiment has been run. (I can’t vouch for what a good management consultant does.) But once both journalists and scientists have discovered something of interest, they want to give their audiences some pointers as to what it is. The same is true for chart designers.

Edward Tufte, the influential information designer, admires graphics that are dense and complex with a minimum of decoration or annotation. The introduction to one of his books, Envisioning Information, sternly warns readers, “The illustrations repay careful study. They are treasures, complex and witty, rich with meaning.” Look hard. Think. Pay attention at the back of the class. For Tufte, the ideal graphic invites the reader to sit down with a cup of coffee and really pore over the details. “Emaciated data-thin designs,” he warns, “provoke suspicions—and rightfully so—about the quality of measurement and analysis.”16

He may be right—although as we should know by now, the data density of the graph is no guarantee that the data themselves are reliable: a graph that presents a few data points in a lighthearted fashion may be unimpeachable, while an intricate graphic may be saturated with bad data.

Even if the numbers are solid, a graphic detailed enough to demand a coffee may be persuasive without also being informative. An impressive example is the New Yorker website’s 2013 presentation of data about inequality. The infographic, designed by Larry Buchanan, evokes the iconic New York City subway map. Viewers can click on different subway lines and see how median income varies along each line. This is an evocative data visualization “duck”: the graphs of rising and falling income resemble subway routes, and they carefully copy the distinctive design elements of the New York subway map and signage.17

What makes the infographic persuasive is that it invites us to make a natural comparison and immediately imagine the people behind it: we observe incomes varying along a chosen line as it moves through different neighborhoods, we grasp the vast inequality encompassed in a brief subway ride, and we picture the characters involved, rubbing shoulders in the subway car. The rich and poor are so close together, so similar in some ways and yet so different. The infographic carries a real emotional punch.

But is it informative? Not so much. As we click around, it is surprisingly hard to learn anything that we didn’t already know. It’s difficult to compare one subway line with another or to spot any but the most obvious patterns.

This becomes clear when we read the brief article accompanying the infographic, which is full of facts that cannot easily be discovered from the graphic itself. The highest median household income of a subway-endowed census tract in New York City was $205,192. The lowest was $12,288. The article tells us the subway lines with the largest and the smallest income ranges, and the largest gap between any two stations, although quite why any of this information is useful is unclear. The blog post notes that income inequality in Manhattan is similar to inequality in Lesotho or Namibia. Is that bad? It sounds bad. If you happened to carry around a list of the income inequality recorded in every country on the planet, you’d realize that it was bad. But do you? The goal of the graphic is not to convey information but to stir feelings. If the article compared income inequality in New York with that in other global cities such as London and Tokyo, or other US cities such as Chicago and Los Angeles, we might actually learn something worth knowing.

The result is gorgeous but far less informative than a map would have been. It is a piece of persuasive art pretending to be a piece of statistical analysis. We’ve been powerfully reminded of something we already believed. We are more passionate, more engaged, but are we truly any more informed?

There’s nothing wrong with a polemic—I write them myself, occasionally—but we should be honest with ourselves about what’s going on.

Another example is a graph by Simon Scarr, a senior designer at Thomson Reuters. The graph depicts deaths in Iraq in each month between 2003 and 2011. It’s an inverted bar graph: the larger the number of deaths that month, the longer the bar hangs down. Scarr colored his bars red, meaning the entire graph looks like blood running down from some awful gash at the top of the page. In case the message was ambiguous, the chart is titled “Iraq’s Bloody Toll.” If Larry Buchanan’s subway-inequality graph tugs at your heartstrings, Scarr’s graph rips your heart right out of your chest. Not for nothing did it win a design award.18 And unlike the subway diagram, Scarr’s graph does give you the relevant information: it is persuasive and informative.

But when Andy Cotgreave, a data visualization expert, saw Scarr’s graph, he tried a little experiment. First, he recolored the graph, showing the same bars in a cool corporate blue-gray. Then he turned it upside down. Finally, he changed the title from “Iraq’s Bloody Toll” to “Iraq: Deaths on the Decline.” The change in the emotional impact is bracing. Scarr’s graph screams raw outrage. Cotgreave’s is sober, almost soothing. Which is the better graph? It depends on the message. Scarr’s graph wails, “Oh, the humanity!” Cotgreave’s graph calmly states, “The worst is behind us.” Both messages are fair. It’s a reminder that the simplest choices of color and alignment can change the tone of a chart and how people will perceive that chart, just as your tone of voice can dramatically alter how your words will be received.19

How could a lowborn statistician, William Farr, and a mere female, Florence Nightingale, win over the stubborn doctors and soldiers of the Victorian establishment?

First, they had to make sure their data were absolutely watertight. Facta, facta! Farr and Nightingale knew very well that their work would be pounced upon by their political enemies. In one telling exchange, Nightingale wrote to Farr warning him to prepare for an attack on his latest statistical analysis. His response showed the confidence he had in the quality of the work: “Let us wait, & keep our powder dry. We are not going to fire in the air—like people frightened out of their wits. Let them point out our ‘mistakes,’ and if they are mistakes—we will admit them freely: but shake our foundations—or blow down our walls—the fellows cannot.”20

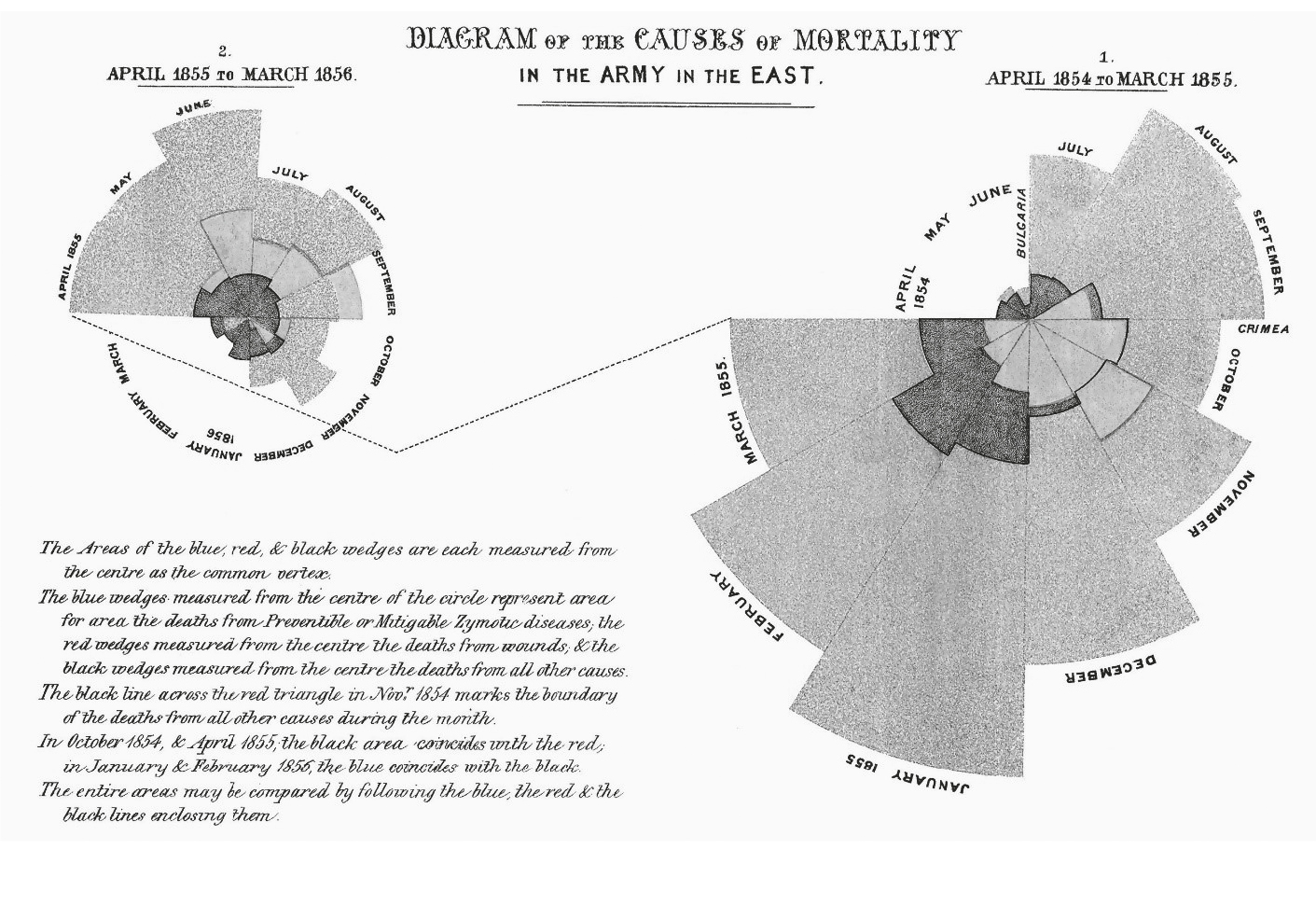

Then they had to present their findings. Nightingale circulated her rose diagram in 1858 and published it early in 1859. That was just a few years after her time at Scutari hospital—and a matter of months after Dr. John Simon’s assertion that contagious diseases were practically unavoidable. The rose diagram (overleaf) is a brilliant visual argument. I’ve seen one of the original prints up close, in the library of the Royal Statistical Society. It’s breathtaking and alarming, a beautiful array of colored wedges showing deaths from infectious diseases before and after the sanitary improvements at Scutari.

If you wanted to be unkind about the diagram, you could say that it is a pie chart on steroids. Technically, it’s a polar area diagram, quite possibly the first such diagram ever created. What it isn’t is a dry presentation of statistical truth. It tells a story.

To see just how powerful a piece of visual rhetoric it is, consider the alternative presentation as a bar chart (the example below is based on a graph by Nightingale’s biographer Hugh Small, using William Farr’s data).

At first glance, Small’s bar chart is far clearer and easier to follow. But it draws the viewer to the wrong conclusion. It focuses attention on the dreadful death toll of January and February 1855, which might lead one to wonder if these deaths were basically caused by a bitter winter, and spring brought relief. It also makes the decline in deaths look dramatic but smooth—a process rather than a sharp change.

The polar area diagram, in contrast, divides the death toll into two periods—before the sanitary improvements and after. In doing so, it visually creates a sharp break that is less than clear in the raw data. Because the polar area diagram plots deaths in proportion to the area of a wedge, rather than the height of a bar, it also slightly obscures just how awful January and February 1855 were, instead lumping them together with the grim bulk of “before the sanitary commission.”

Nightingale wanted to make the importance of improved sanitation leap off the page, convincing the viewer that the Scutari experience could be repeated in hospitals, barracks, and even private dwellings across the British Empire. She created the powerful “before and after” structure of the diagram to strengthen that argument.

Is this dazzle camouflage? Perhaps. I’m inclined to say it isn’t, if only because the data are rock solid and there in plain sight. Unlike Debtris, it doesn’t rely on patchy statistics and unhelpful comparisons; unlike the subway-inequality diagram, it isn’t all sizzle and no steak. It’s more like “Iraq’s Bloody Toll,” but it is far more subtle in the way it invites readers to draw their conclusions. Few discussions of the rose diagram highlight just how clever it is at directing the reader toward one interpretation of the data and not another. Thankfully the idea was both true and important; the visual rhetoric helped people to reach a conclusion that happened to be correct.

Nightingale explained to Sidney Herbert that the diagram “is to affect thro’ the Eyes what we may fail to convey to the brains of the public through their word-proof eyes.” To get her diagram in front of as many eyes as possible, Nightingale asked the radical writer Harriet Martineau to produce a moving book about the Crimean War and the suffering of British soldiers there. Martineau had read Nightingale’s reports and praised them as “one of the most remarkable political or social productions ever seen.” Nightingale included her polar area diagram as a foldout frontispiece in Martineau’s book. It didn’t get read by as many soldiers as it might have done—the army banned it from military libraries and barracks21—but Nightingale had a more particular audience in mind for her diagram, as she told Herbert:

None but scientific men even look into the appendices of a Report, and this is for the vulgar public . . . Now, who is the vulgar public who is to have it? (1) The queen (2) Prince Albert . . . (7) all the crown heads in Europe, through the ambassadors or ministers of each (8) all the commanding officers in the army (9) all the regimental surgeons and medical officers . . . (10) the chief sanitarians in both houses [of Parliament] (11) all the newspapers, reviews and magazines.

The senior doctors who had argued that there was nothing to be done gradually came around to Nightingale’s argument for better sanitation. In the 1870s, Parliament passed several public health acts. Death rates in the UK began to fall, and life expectancy to rise.

What makes Florence Nightingale’s story so striking is that she was able to see that statistics could be tools and weapons at the same time. She appreciated the importance of solid foundations such as the tedious tasks of standardizing definitions and getting everyone to fill in the right forms, and of producing “the dryest of all” analyses, impervious to attack from the critics. But she also understood the need to give the data a makeover, presenting them in the most persuasive light. She produced a picture with enough power to change the world.

Florence Nightingale was on the right side of history, but many of the people who misuse catchy graphics are not. For those of us on the receiving end of beautiful visualizations, everything we’ve learned so far in this book applies.

First—and most important, since the visual sense can be so visceral—check your emotional response. Pause for a moment to notice how the graph makes you feel: triumphant, defensive, angry, celebratory? Take that feeling into account.

Second, check that you understand the basics behind the graph. What do the axes actually mean? Do you understand what is being measured or counted? Do you have the context to understand, or is the graph showing just a few data points? If the graph reflects complex analysis or the results of an experiment, do you understand what is being done? If you’re not in a position to evaluate that personally, do you trust those who were? (Or have you, perhaps, sought a second opinion?)

When you look at data visualizations, you’ll do much better if you recognize that someone may well be trying to persuade you of something. There is nothing wrong with artfully persuasive graphs, any more than with artfully persuasive words. And there is nothing wrong with being persuaded and changing your mind. That’s our next subject.