36

Babe does not like to talk about the dissolution of his first marriage. How much of what was written can be true, Babe asks, when even the spelling of his ex-wife’s name is open to dispute?

Babe and Madelyn had a dog, Babe Junior, and a Capuchin monkey, Babe the Third, in lieu of children.

It was not a marriage, Babe tells him. It was a zoo.

He is aware of something of the history, but mostly through whispers, and what he read in the gossip columns before he met Babe, when he could still take some small pleasure in another man’s miseries, if only because they diminished his own.

Babe likes women.

And women like Babe.

Madelyn knows this, or guesses it. She can smell them on Babe, their sweat mingling with her husband’s, corrupting his scent. Perhaps it might have been different had she and Babe stayed in Georgia, but probably not. Babe would have tired of her eventually: tired of her plainness, and the toll taken by the years, particularly as the gap in their ages began to tell. But fewer opportunities would have arisen in Georgia for Babe to stray. In Georgia, Babe would have been just another fat fool running a theater.

And she does love Babe, just as Babe once loved her, which makes the humiliation so much worse.

The disintegration of the marriage is a horror show, a public spectacle. A separation agreement collapses because Babe falls behind in his weekly maintenance payments of $30, and then ceases to pay anything at all. Madelyn considers filing for divorce, but early in 1920 the health of her father, Louis, deteriorates. Babe, she claims, urges her to travel to Atlanta to be with Louis at the last. Babe describes the divorce suit as a nonsense, and intimates—or so Madelyn believes—that a reconciliation may be possible.

Madelyn arrives in Atlanta in time to bury her father, and Babe sends a telegram instructing her not to return to Los Angeles.

I WILL NOT RECEIVE YOU AS MY WIFE.

But Madelyn does return, and Babe initiates a divorce suit. Babe alleges verbal abuse. Babe alleges physical assault. Babe alleges trickery into marriage through Madelyn’s false claims of pregnancy. Babe claims not yet to have reached his majority when Madelyn inveigled him into their union.

Babe lies, or permits his lawyers to lie for him. Perhaps Madelyn does the same, but still, he does not like to think of Babe as a liar. Together, Babe and Madelyn put to the torch any memories of happiness they might once have enjoyed, and sow the seeds of troubles to come.

Babe’s allegations prevail. To compound Madelyn’s abasement, a restraining order is obtained against her, because Madelyn is not a star. Madelyn is just a former piano player and singer. Babe Hardy is in pictures, and must be protected.

And waiting in the wings (but how long has she been waiting? This, too, is one of Babe’s secrets) is Myrtle Reeves, soon to be the second Mrs. Oliver N. Hardy. Babe is rooming with Myrtle and her sister. Everything is above board. Nothing to see here.

Madelyn is no fool. The name Myrtle Reeves is already on her lips, and passes in a whisper to the ears of her lawyer. Madelyn counter-sues, and is granted an interlocutory decree.

A sham, Babe later tells him, but Babe will not meet his eyes.

Madelyn gets her $30 a week, but does not ask for alimony. This, he thinks, says much about her.

He does not inquire who got to keep the dog and the Capuchin monkey.

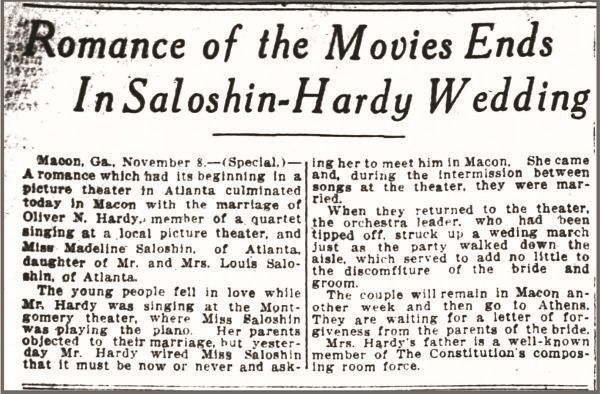

One year later, with the ink still wet on the final decree, there is another wedding, and another press cutting:

Vitagraph, safeguarding its investment in Babe, does its job.

Babe and Myrtle are childhood sweethearts back in Atlanta.

Babe sends Myrtle her first Valentine when she is ten years old (and Babe is fifteen, if this is to be believed).

Babe and Myrtle wed after Babe has paid court to her “for some time.”

This, at least, is true.

Of Madelyn, there is no mention. She has been bought off so that Babe may rest easy in the arms of his new bride, his life story rewritten. Now Babe will never have to think of Madelyn again.

If Babe believes this, Babe is a fool.