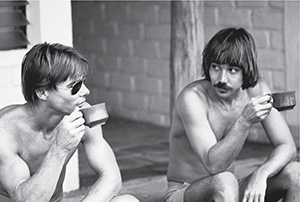

My Big Wednesday costume and prop: trunks and surfboard were all that was needed for this hollywood surf movie. Photo: Art Brewer

Jan’s Board

My Big Wednesday costume and prop: trunks and surfboard were all that was needed for this hollywood surf movie. Photo: Art Brewer

I was at home that day; the surf hadn’t been exciting enough to make the long, narrow, winding drive down the hill for a closer look. From my front window I could see the sweep of the north shore of Maui, and at a glance the paucity of whitewater lines told the story. The waves were flat. It was a day to curl up with a book on the couch and rest. The surf, on its own schedule, would come the following day or some day thereafter.

As it happened, I was stretched out on the couch when the phone rang, startling me with its shrill ring in the silence of upcountry Olinda, high up on the slope of the Haleakala volcano. My golden retriever, Blue, raised an eyebrow at the sound, glanced toward the couch to determine whether action on my part was forthcoming, shifted positions, sighed loudly, and slipped back into that wonderful instant slumber only dogs of his ilk can achieve.

Normally I could rest, not in the least disturbed by the ringing phone. I might vaguely count the number of rings until it stopped, feeling no guilt whatsoever for not summoning the energy to connect with the person making the effort to call. It was a bad habit, but I enjoyed the solitude of my home high in the hills. I justified my unwillingness to be imposed on by thinking that he or she would call back if it was important. For some unclear reason this time I rolled up off the couch, took the required three steps, grabbed the phone off its hook, and returned to my supine position on the couch before answering.

“Hello,” I said into the receiver.

Afterward, I would wonder whether maybe subconsciously I had some inkling that this phone call would be different because making that connection would, quite literally, turn my quiet life upside down in the months to come.

“Hello,” a strange woman’s voice said. “Is this Gerry Lopez?”

“Yes it is,” I replied, thinking who in the heck could this be now.

“Will you please hold for John Milius?” I heard the click of the call being transferred, and before I could wonder who John Milius was, although the name did sound vaguely familiar, a strong voice came on the line.

“Gerry? Hi, this is John Milius, how are you?”

“Well, I’m fine … John, do we know each other?” I had to ask because I was at a loss to place the name.

“Not yet, not yet,” he quickly answered. “But we will. Let me explain.”

He went on to tell me how Warner Bros. Studios was producing a movie about surfing. He and a guy named Denny Aaberg had written the script. It would be called Big Wednesday. There was a cameo part in it that he wanted me to play. My old friend surf-filmmaker Greg MacGillivray would be directing a second unit to film the surfing sequences.

I listened and wondered what the heck a cameo appearance or a second unit might be, but I marginally understood the importance of our conversation. This was Hollywood calling. This was the call that everyone dreams about. I checked whether I was still breathing. Even Blue was awake now, watching me closely, sensing something in the air.

A few days later I was driving on Ventura Highway and following the directions John’s secretary had given me. I came around a curve and over a slight rise, and there sprawled before me was the small city that is Warner Bros. Studios. A big sign told me I was at my destination. A huge fence ran, I imagined, around the entire complex. The fence ran as far as I could see to either side of the gate I was approaching, at least a mile in both directions.

A guard gave me directions to the Big Wednesday office. I drove down row after row of huge metal buildings that were all separate sound stages. Everywhere there were extras in costume: cowboys, Romans, 1920s zoot-suiters, showgirls … the works.

I drove past a completely deserted suburban neighborhood with 1950s-style houses lining the street. The next street was a typical turn-of-the-century city, with old buildings and businesses bunched together. As I passed I saw that these were only false fronts. There was another row of false fronts backed against them. I passed a dirt street of a Western cowboy town complete with saloons, horse troughs, and hitching rails. I was in Hollywood, Tinsel Town. Only a few days before, I had been sprawled on my couch in a different life.

I gave my name to the series of secretaries and moved deeper into the inner sanctum of the temporary Big Wednesday production office. John’s personal assistant greeted me.

Then John, a bear of a man, rushed forward, shook my hand, and ushered me into his small office saying, “Glad you could make it, this is great, we’re going to make a terrific film.”

He went on to fill me in on many details of the upcoming production. I was in a Hollywood daze, barely hearing what he said as a host of different crew members trooped through John’s office to ask some question or another and briefly say hello to me. The producer, Buzz Feitshans, joined us and informed me of “my deal,” membership in the Screen Actors Guild, and other pertinent information regarding my new employment.

“Sure, it all sounds good” was all the answer I could muster.

My new Hollywood experience peaked when the star of the show, Jan-Michael Vincent, walked in with his rugged good looks. Only a short time before I had watched him on the big screen in “The Mechanic” with Charles Bronson; now I was meeting him in person.

The general atmosphere of informality surprised me. Hollywood always had seemed to me distant and larger than life. I was stunned to recognize that, when it came right down to it, these people were just regular folks like me.

Jan-Michael and I became fast friends. His successful acting career didn’t prevent Jan from being an avid surfer, and we had a lot in common. I was a regular guest at his Encinal Canyon home during the L.A. shooting portion of the movie. I had only light surfboard-shaping responsibilities for my business, Lightning Bolt Surf Company, and even lighter duties to the Bolt Corporation, our licensing company. I was free to play my new Hollywood role.

And quite a role it was. Besides reveling in the glamour of the movie-making process, I also enjoyed a spectacular social life hanging with the stars. Gary Busey, the other main actor, was married and had a young son but spent most nights out on the town with us. Mostly those evenings were spent watching Jan operate. He was the consummate ladies’ man; the women loved him, and he was seldom without their company. He was separated from his wife, a situation common to the tabloid lifestyle of Hollywood.

Jan-Michael Vincent and me enjoying a quiet morning moment before the start of filming. Photo: Dan Merkel

During the next several months of partying with him, I understood why Jan’s movie-star nightlife couldn’t support a marriage. Near the end of the shooting I reached my limit. I awoke one afternoon and knew I was done. We stayed up far too late to enjoy any sunrises or mornings, unless we stayed up the entire night. High on the hillside, Jan’s home had a view of Point Zero and Zuma Beach. I could see a swell running but the wind had already blown out the waves. Jan was still asleep, and it was too late to catch any good waves. I was disgusted with myself. From that moment forward, I vowed never to drink or party like that again. That was thirty years ago, and I haven’t had another drink since.

The moviemaking was fun. Most of the filming was done on the Warner Bros. lot where sets already were in place. A few scenes were shot on location. The draft board scene was filmed in the actual building where the draft board conducted the physical exams prior to sending those selected away to Vietnam. Another scene required a pier where the ‘Bear’ had his bait and surf shop. That location was the Gaviota Pier north of Santa Barbara.

Big Wednesday is a movie about three friends who grow up surfing Malibu in the early 1960s and spans the carefree years of youth when the movie characters, Matt, Jack, and Leroy, live to surf and little else matters. Come the early 1970s, the friends get jobs, have families, move away, and leave their youth behind. Big Wednesday is a day when the surf gets bigger than ever before, reuniting them one final time. It’s a movie about youth and friendship. The details are exacting. John Milius and Denny Aaberg had spent a portion of their own youth surfing the ‘Point’ and hanging out in the ‘Pit.’ They set out to re-create authentically what for them had been the sweetest of times.

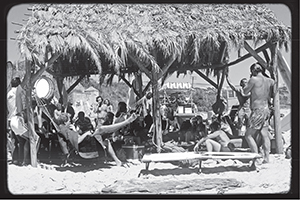

By far the best location work was where they set up the Pit area. The Pit was painstakingly re-created in amazing detail at Cojo Point on the Bixby Ranch, just north of the famous Hollister Ranch. Cojo is a perfect right point, highly coveted during the south swell season but entirely off-limits because of the privately owned ranchland. Cojo’s splendid waves break mostly unridden, except by adventurous boat-in surfers.

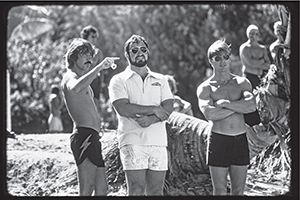

I’m pointing out some nuances of the break to John Milius, the director, and Jan-Michael Vincent, the leading actor, before we all paddled out for their first attempt at surfing some big waves at Sunset Beach. Photo: dan Merkel

One of the sets at Cojo on the Bixby ranch built to look like the Pit at Malibu of the early 1960s. Photo: dan Merkel

For three wonderful weeks Hollywood moved in and took over, renting the area from the Bixby Ranch. The cast and crew were housed in nearby Lompoc, but Jan and I were exempted. His personal motor home, a classic Airstream, was leased by the production company for his own use during the entire shoot and parked on location. It was quite a deal. The movie paid him to use his own motor home.

It was my first experience with a motor home. I marveled at this complete home on wheels. For the entire three weeks, Jan and I spent our nights on the set. We would awaken on many occasions to the quiet solitude of Cojo Point with perfectly peeling waves. There was a night watchman, but we never saw nor heard him. The catering manager would make sure he left a large tray of food and drink for our dinners each evening. Every day, two busloads of beautiful Santa Barbara girls were hired as extras and bussed to the location. Jan would work his charm and magic to entice some of them to camp out for the night.

Despite the excesses of his nightlife, Jan was a professional when it came time to do the job. When the director said, “Action,” Jan delivered his lines perfectly. That he had been up the entire night before drinking didn’t matter. It helped that the character he played was supposed to be drunk most of the time, but still it was amazing to see him perform.

Acting isn’t easy. To do it well takes a lot of—well, I’m not sure what. Believable acting takes talent, but also lots of concentration, dedication, and focus. Many actors are professionally trained, spending years at acting schools or with private acting coaches. Some use what is known in the film industry as “method acting,” where they substitute a previous personal experience to set the mood for the particular emotion required by the scene. Jan was a completely natural actor, able to get into his role with little preparation or research.

I had done some very lightweight acting in a few surfing movies. In the surf movie scene for Big Wednesday, I was only required to play myself, walk through the crowd, and make brief eye contact with Matt. The location was an old theater that actually had been used to show surf movies during the 1960s. John and Denny wanted every detail of the movie to be authentic in order to preserve on film the nuances of their former lives.

I had no lines to speak and only a moment on film, but I was nervous to a point near catatonia. Jan noticed my discomfort on the first rehearsal and gave me some pointers. He simply told me to remember being at a real surf movie and to re-create that memory here. It was my first lesson in method acting.

There was a scene on the Cojo set that required a little more from me. In the scene I would drive to the beach during the big swell, get out of the car, and pull my surfboard out of the back. When the time came to shoot the scene a small problem became apparent. I didn’t have a surfboard to take out of the car.

Luckily, I had made a surfboard for Jan. It was an 8’0” Lightning Bolt with an orange bottom, red deck, and black and white bolts. It was inside his motor home. One of the assistant directors rushed to fetch the board and we shot the scene. Later when we filmed the surfing sequences in Hawai’i, I built myself a matching board. At that point the producers decided that only the big winter surf at Sunset Beach could make the necessary impression. So the new plan was that we would finish the movie on North Shore, O’ahu.

The water unit, main stars, and quite a few of the crew enjoyed a nice month at the Kuilima Hotel while shooting film all over the North Shore for that final day of the story. I made a new board to ride big Sunset, glassed exactly the same as Jan’s board. George Greenough and Dan Merkel took some heavy wipeouts filming from the water at inside Sunset with bulky and unwieldy 35mm cameras in water housings. Greg MacGillivray masterfully directed all of the shooting from shore. His brilliant editing of the footage created an exciting and totally believable final surfing scene.

The Big Wednesday of surf did indeed come across as a day like no other. The main character’s (Matt Johnson) surfing, cleverly doubled by Billy Hamilton and J Riddle, was spectacular. Jan did some of his own surfing at Sunset. Although a bit outgunned by the premier North Shore surf spot, he definitely set a high bar for actors and was dubbed “the best surfer in Hollywood.” His real-life surfing allowed the editing team to cut to close-ups in the surf sequences, which helped to sell the scene.

In the movie, the three friends come back to their favorite break, and although now considerably older and perhaps slightly over-the-hill, they rip it up one last time. Matt takes a vicious wipeout on his last wave, ending his surfing career. He passes his special big-wave board, built by the Bear, on to one of the younger surfers when he gets back to the beach. For the wipeout the stunt coordinator, Terry Leonard, hired Bruce Raymond, now a chief executive at Quiksilver International, but then a starving young surfer. For $100, Bruce paddled himself over the falls on wave after wave until Terry, the second unit director called, “Cut!”

After reviewing the daily film, both MacGillivray and Milius decided that Sunset Beach just didn’t look terrible enough. They came up with an idea to get a goofy-foot surfer to take some gas at the Pipeline; they would flop the negative to make the left become a right. For another $100, Jackie Dunn agreed to be the human dummy. Why anyone would deliberately launch himself into space again and again at the Pipe was beyond me.

Flipping the negative cut perfectly into the film sequence. Jackie Dunn actually looked much more like Jan than did either of the other stunt doubles. Apart from breaking several of the prop boards, shaped by Tom Parrish and airbrushed to look like balsawood—and probably almost breaking his neck—Jackie was little worse for wear after the stunt. The final sequence of the movie was a complete success.

Big Wednesday, authentic in every detail, well-acted, well-directed, and a cinematographic tribute to the sport of surfing, was doomed to a life of mediocrity. Rejected by the suits at Warner Bros. Studios, the film was sold in a package deal to an independent distributor rather than marketed by the formidable studio distribution system. This decision precluded allocation of any large marketing dollars to help sell the film to the public. Even the surf media reviews of the movie were lackluster to outright negative. Big Wednesday wasn’t going anywhere in the U.S. Nobody wanted to know about longboard surfing in 1978.

Ironically, the film enjoyed great success in both Italy and Japan, quickly becoming a cult classic and enjoyed for years. However, Big Wednesday had a snowball effect on the surf world in several ways. Not only did it become a standard by which the era depicted would forever be measured, but it also single-handedly launched a resurgence of longboard surfing that took the surf world by storm a few short years later.

Big Wednesday rose to its well-deserved prominence eventually, but only by coming in through the back door. Real surfers found this to be appropriate. Just like its subject matter, acceptance was based on the unspoken and unacknowledged nature of the sport.

Despite the negative public opinion that pervaded mainstream culture during surfing’s first ascension to notoriety in the 1960s, our way of life continued to grow. Surfing is, for surfers, the only life, and will always be the only life. Today the surf industry is mainstream, but like the rip currents that are common to many of the best surfing areas, the sport and the lifestyle it spawned had to battle against the current to gain acceptance from nonsurfers.

Ironically, the only surfboards from the early shortboard period that remain in my possession are the Big Wednesday boards. Somehow the one I rode at Sunset during the filming, and Jan’s board, escaped the rubbish heap. Hi-Tech Maui, the premier surf and water sports store on Maui, used them for display boards. This further helped them to avoid being sold or thrown away. Randy Rarick recently sold Jan’s board at his world famous surf auction. It was a beat-up old board that had definitely seen better days, but it had a superb pedigree. It sold for more than $12,000.