The Track of the Cat

Shoe stores in Hawai’i must not have done much business with children’s shoes during the 1950s. No kid I knew wore shoes when we were growing up. The first time I owned a pair of shoes was when I was entering seventh grade. Until then everyone went barefoot.

The best thing about not wearing shoes was that the soles of our feet got so tough that they were impervious to kiawe thorns or hot pavement. With the bottoms of our feet like leather, it was as though we had a pair of built-on shoes. My grandmother would throw us out of her house in the morning. Because we had dirty feet, we couldn’t come back inside until we took a bath that evening and washed our feet before dinner.

The surf lifestyle was not particularly big on shoes either. Who needs them at the beach? After an early, and brief, surf fashion statement with Sperry Top-Siders and huarache sandals, most Hawai’i surfers just wore rubber slippers if they didn’t go barefoot. For us, dressing for comfort and not for speed was more in line with being a surfer.

Growing up in Hawai’i was the perfect place to dial in the minimalist surf dress code. A pair of shorts, a tee shirt, and a surfboard were all a surfer needed. But a cool pair of trunks wasn’t easy to find in the early days. There weren’t any Quiksilver or Billabong surf companies making functional and stylish surf trunks. Surfers in the know would go to a custom sewing shop like Take’s, M. Nii’s, or H. Miura’s, be fitted for shorts, pick the fabric, and practically live in that pair of shorts once delivered. A couple of tee shirts rounded out the uniform.

On early trips to Bali, Indonesia, we reverted back to those carefree days of youth. We packed a couple of pairs of shorts, a small stack of tee shirts, two or three surfboards, and a sturdy pair of Rainbow Sandals. But the beaches were clean, so once we arrived we ditched the slippers and toughened up our feet that had grown soft from too many years of wearing shoes.

One of the big training programs that became part of our Bali lifestyle was the run-swim-run. We would start from Mike Boyum’s house near Kuta Beach and run down the dirt road barefoot and along the shore in our Speedos, swim goggles on our heads. It was easier to run on the packed wet sand near the water’s edge, but it was a better workout to run in the soft sand further up the bank. The dry sand, however, was hot. There was a risk of burning our feet if we hadn’t broken them in properly.

This breaking in was a careful process of feeling the soles of our feet getting hot, then dashing down to the wet sand to cool them off before resuming the run in the hot soft sand. After several miles of running, we would jump in the water and swim back about halfway, then run the rest of the way home. It was a great workout, and we did it religiously whenever the surf was small. If the surf was up, of course we just went surfing all day.

One day when the waves were small we did an early yoga session and decided we would extend the run and swim distances. We wanted to come back and reward ourselves with a big lunch without feeling guilty about eating too much when there was no surf. So we headed out in the midmorning. The sky was clear, the trade winds had kicked in combing the small wave faces into perfection, and it was a joy to run along the seashore watching the surf. Occasionally a wave would peel and we would mind surf it. We imagined turns, cutbacks, off-the-lips, and tuberides. In that way we received all that those waves offered.

Several miles down the beach was another little village called Legian where there was a hotel, more losmen, and some small shops. I guess Kuta and Legian had been there a long time, because both had very old temples and huge trees. The big trees were a sure sign that people had been living in an area, as they provided a priceless service: shade.

The sunshine of Bali is deceptively inviting. Overexposure can be serious. Light-skinned tourists not acclimated to the intensity of the sun near the equator pay dearly. For very obvious reasons, local people value shade, and cutting down a shade tree is a high crime. If the numerous large shade trees were any indication, Legian was probably a more popular area than Kuta at one time.

Kuta grew quickly with the recent influx of Australian and American tourists looking for less spendy digs. But Legian has something the beachbreaks of Kuta will never have, which may have a big effect on future growth, at least for surfers. There is a more pronounced bend in the curve of the beach at Legian, which affects the riptides. Sometimes as a result of these rips a sandbar will form creating beachbreak waves of world-class shape. I had heard about this break, but until this day I had not seen it.

Mike and I were running up the beach and could see surfers in the water, but we were still too far away to make out any detail. As we got closer we saw the surfers getting long rides, unusual in shorebreaks unless they are really good. In Hawai’i there are not many beachbreaks well suited to surfing—bodysurfing yes, but not boardsurfing. To a surfer raised on reefbreaks, and with the excellent reefbreaks of Uluwatu and Kuta Reef, the beachbreaks of Bali didn’t hold much appeal for me.

But, we could see as we came closer, this Legian break was as near perfection as a beachbreak can be. Maybe the surf was coming up, because the waves looked really good. The surfers were all sitting in one spot where a nice peak consistently broke. Sometimes it would break better left, other times to the right, but most often it went both ways equally clean. It appeared that the right was giving longer rides, all the way into the knee-deep water inside. Hot and sweaty from our long run, we stood there in shock, watching wave after wave peel off.

Back then there were not a lot of surfers on Bali. The more skilled ones naturally gravitated to the better reefbreaks, while those of lesser skills enjoyed the more gentle waves on the beaches. The level of surfing was not quite up to the quality of the waves on that day with one exception. We had seen one guy styling across a wave when we were still a distance away, too far to tell much except that he got a long ride.

As we stood nearer the break he caught another wave, but as he made his first turn some beginner took off in front of him going straight off and he was forced to kick out. There was something very familiar about his surfing style. A few minutes later, he caught a wave that somehow reminded me of First Point Malibu as it peels into the Cove.

Watching this guy climb and drop, smoothly cutting under the whitewater when the wave sectioned ahead before sweeping back up onto the green, I realized why the wave looked like Malibu. It was because this guy surfed just like Miki Dora, the King of Malibu. He rode the wave to its end, kicked out, and paddled back to the peak.

We sat and watched more rides, waiting for the good surfer to get another one. When he did, again he rode just like Dora: the characteristic slouch, knees forward, upper body leaning back, the hands held stylishly. Either this had to be the real thing or the best imposter I had ever seen.

“Mike, let’s swim out there and see who that is, I think it’s Miki Dora,” I said.

Mike knew the history of Dora and was as keen as I was to see if this was really him. So we put on our goggles and swam out to the lineup.

“Hey Miki,” I yelled when we got close, but he glanced sideways at us, turned the other way and paddled for a wave.

We waited until he paddled back out, but could tell he was trying to avoid us. I’m sure we looked like two geeks in our swim goggles and Speedos swimming after him in the lineup. Every time we tried to get close, he would just move away. He had much more mobility on his surfboard than we did swimming.

We weren’t getting anywhere this way, so I suggested to Mike that we run back and get our surfboards. So we ran back to the house as fast as we could, grabbed our boards and a motorbike and blasted back. I drove while Mike sat behind holding both surfboards. Back then nobody cared if we drove on the beach because there were so few people. We knew all the lifeguards anyway.

We got back to Legian, parked the bike, and paddled out. He was still there, sitting farthest outside alone. Mike and I paddled up and introduced ourselves.

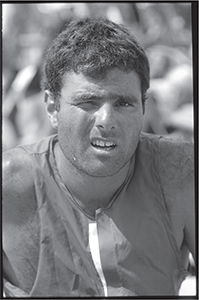

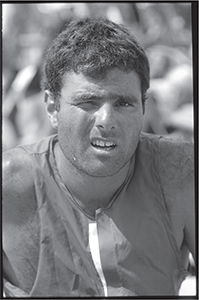

Miki dora styling through another section at Malibu. Photo: Leroy Grannis

“Hi Miki, I’m Gerry and this is Mike,” I said.

“I think you’ve got me mixed up with someone else,” was all he said, but the furtive head gestures and shifty eyes gave him away.

“You’re Miki Dora and you’re our hero; what are you doing here?” I blurted out.

“Are you guys FBI?” was the only answer.

“FBI? If you mean feeble-brained idiots, yeah I guess so. What the hell kind of question is that?” I was puzzled.

“Well, you don’t look like federal agents, but if I ask and you are, you have to say so,” he answered.

“So you’re Miki Dora and you’re here in Bali. What’s going on?” Mike and I wanted to know.

“I might be who you say, but don’t say it out loud any more. I don’t know who the rest of these guys are,” he gestured toward the other surfers around us who sat there totally oblivious to our conversation or our identities, their only interest being the next set of waves.

“You guys live here? You know where the good surf is?” he asked.

“Yeah, you want to go out and surf some bigger waves at Ulu? Where are you staying, we can send a bemo around to pick you up and head out there right now, if you want. It kinda looks like the surf came up a little so it should be pretty good out there,” I replied.

Being in the presence of the Great Miki Dora had us nervously motor-mouthing. But after all we had, more or less, the undivided attention of one of the biggest legends in modern surfing.

He looked at us a little suspiciously, but it seemed like it was his first trip to Bali and we sensed a kindred spirit of adventure in him. He agreed, told us where to find him, and that was how we first met Miki ‘da Cat’ Dora.

We picked him up at his losmen in our bemo-for-the-day. A bemo is a small Datsun pickup with a covered bed and bench seats along each side. They serve as the main means of transport for the local people. A bemo was the best way to get ourselves and our surfboards out to Ulu. The exhaust fumes flowing into the open back mingle with the rest of the too-numerous-to-list odors that permeate the Balinese atmosphere. We were well used to it, but Miki’s discomfort was evident.

“I’m used to a little higher standard of transportation; is this all that’s available?” he asked as we bounced along the road to Uluwatu.

In contrast to our dirty surf trunks, grubby tee shirts, and dusty running shoes, Miki was dressed immaculately in a stylish tennis outfit with sparkling white tennis shoes.

Forty-five minutes later, after a bumpy ride over a twisted narrow road, our bemo pulled off under some trees. As always a group of young kids waited for our arrival. They greeted us with big smiles and shouts of “me carry, me carry,” as they jostled each other hoping to get picked to carry one of our surfboards down the trail to the waves.

Miki was pretty game after we informed him of the three-kilometer hike to get to the surf. I think it was the young board carriers that made the difference. If he had to carry his own surfboard up and down the rugged path in the boiling midday sun, he might not have been so willing. Mike and I took off running as was our usual practice, a warm-up before the waves. Miki took one incredulous look at us and said he would stay with the surfboards and their carriers.

“I think you’ve got me mixed up with someone else,” was all he said, but the furtive head gestures and shifty eyes gave him away.

When we got to where we could see the surf, one glance showed us that the swell had come up. After a few days of no surf, Mike and I were raring to go. We climbed down the rickety tied-together sticks into the sea cave that was the easiest access to the shoreline along the steep, rugged limestone cliffs at Uluwatu. Eventually, the boys brought our boards down the makeshift ladder in their bare feet, as surefooted as monkeys.

Dora, perched above, called down to us, “I’m supposed to climb down this?”

I guess at first sight the final part of the trail didn’t look very secure, and it would have been a long, ugly fall. Actually, it was an ingeniously designed, although very primitive, ladder system that worked perfectly well, until it fell apart and had to be rebuilt. Miki came down the ladder very tentatively.

“So how’s the surf look?” Miki asked. The board carriers, interested in neither the waves nor in Miki following, had come straight to the cave without bothering to take a look.

“It’s good, it came up,” I answered, as Mike and I waxed up, eager to get into the water.

“Well, where do you paddle out?” Miki asked as he got his own equipment ready.

“No sweat, just follow us right out of this cave and you’ll see the lineup,” I told him. He looked at us a little dubiously as we strapped on our leashes and pointed the way.

The paddle out from the cave at Uluwatu is normally a stunning experience. Paddling out of the darkness into the sunlight to be greeted by a panorama of beautiful surf after the long, hot hike feels like finding the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. This time was an altogether different reward. Apparently I hadn’t done my surf check diligently enough. When I burst out into the sun, instead of a sigh of joy, I uttered a serious, “Oh Shit!”

The swell was a lot bigger and more powerful than I had expected: eight- to ten-foot waves crashed down in relentless fury. The tide, at its peak, coupled with the strong surf, produced a rip of prodigious strength. I was immediately swept sideways, backed up against the rugged cliffs, fighting desperately to keep from being washed into the rocks. Normally it’s a two-minute paddle out. I struggled for a difficult fifteen to twenty minutes before finally breaching the surfline, at which point I saw that the sweep had carried me over a half-mile down the shoreline.

Once through the waves, I started the long paddle back up to the lineup in front of the cave. Mike joined me a short time later, having been right behind me as we went out of the cave. In the riptide and breaking waves, we separated, and it was every man for himself with no stopping along the way.

Over an hour later, Miki came paddling out. “Is that how the paddle out is every time?” he deadpanned.

Not knowing what to expect, he had followed us out from the cave and was caught in the rip. There was no turning back nor any relaxing. He had to battle to keep from being pushed up into the rocks at the base of the cliff. Finally, much further down than Mike and I had been swept, he managed to break through the surf and get outside.

“So is getting back in as exciting as trying to get out?” he wanted to know.

I knew that we had to wait until the tide went out and were kind of stuck out there. It was possible to go in to the small beach just upstream from the cave, but at high tide there was no escape. The tunnel back into the cave would be underwater and practically impassable. If a surfer was lucky he might ride a wave right into the cave entrance, but if he missed, it would be a repeat of the paddle out. Mike and I informed Miki of all this. He calmly took it all in, but I’m sure he thought we were a couple of lame turkeys.

Trying to make up for the surf thrashing, we took Miki to dinner at the Sunset Beach Hotel. The owner there, Francois Faust, was from the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, he had moved to Bali, married a Javanese gal, and had two little boys. He not only ran a great hotel where I usually stayed but also put on a great meal each night.

Miki questioned Francois about whether he had been a Hitler Youth who had fled Europe after World War II. Francois ignored Miki while I tried, to no avail, to let Miki know that Francois and I were about the same age, both born well after the war.

Francois’ friend, Hans Snell, a Dutch artist and also married to an Indonesian and living up in Ubud where he sold his beautiful paintings, had brought his family down to have dinner at the hotel. Miki insisted that Hans looked like an ex-SS man and both Francois and Hans belonged to an Indonesian cell of ex-Nazis hiding out in Bali.

This was more than a little embarrassing for Mike and me. It appeared that Miki had some obsession with Nazi Germany; I’m sure the wine with dinner didn’t help. Apparently Miki’s ranting didn’t make any impression on our host or his friend, and as most nights in Surf City Bali, ours thankfully ended early. We left it with Miki that we would meet him early the following morning to see whether we were surfing or doing something else.

The next day, our ill-fated surf adventure behind us, the surf had dropped dramatically. An unusual storm swell, intense but short-lived, was probably the reason for our rough handling at Uluwatu the day before. Overall, that day of surfing had not been Miki’s best, nor ours.

With the surf gone and the day still young, we thought a run-swim-run would be a good thing. Miki somewhat reluctantly agreed to accompany us. He declined a pair of Speedos but accepted the swim goggles as we stripped down to our essential equipment. We always started out running near the water’s edge but as we left the lifeguard station behind, the beach quickly became devoid of people. We moved up into the soft sand and Miki followed us as we concentrated on our breathing and pace. The sun was up, the day warm, the air clean and fresh, and the sea sparkling off to our left.

Suddenly Miki veered down toward the water, ran right in, and sat down. Mike and I stopped, looked at each other, and went down to see what was going on. Miki was sitting in the shallow water looking at the soles of his feet.

“Are you guys some kind of masochists or what?” he said.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“That hot sand just burned the shit out of my feet, didn’t you guys feel that? Are you torturing me just for fun, or did someone put you up to this? Yeah, you can go ahead, I think I’ll just stay right here.” Miki was done for the day.

He waved us on, cooling his hot feet in the water. I guess those California guys didn’t go barefoot enough because the sand wasn’t that hot yet, and we were less than ten minutes into the run. Mike and I kept going, feeling bad about trying to show Miki Dora a good time in Bali and doing a terrible job of it. We didn’t get to surf with Miki any more over the next ten days we spent with him, but he schooled us in a fierce way at tennis, which he played expertly.

A year or so later, I found out that Miki was on the run from the FBI for some crime he allegedly had been involved in. Apparently they caught up with him. I think the story goes that the FBI always gets their man.

Many years later, I ran into Miki in Biarritz, France, at a dinner party in another friend’s home. I asked him if he remembered the brief time we had spent together in Bali. He answered with a trademark Miki Dora hand gesture and a twinkle in his eye: “You must have me confused with someone else.”