Photo: Jeff Divine

Momentary Entertainment

Photo: Jeff Divine

The surf at G-Land had always produced for us. Year after year, trip after trip, the waves pumped. We came to expect it, thinking this was just the way it always would be. But the reality of surf is that it is almost never consistently reliable. That is one of its greatest lessons: To lessen disappointment, one must first lessen expectation.

The surfing experience teaches this lesson over and over again on a regular basis. How many times does a surf report instill high hopes that are only dashed, when after much effort the surfer finally arrives at the seashore to find no waves at all?

The good thing about G-Land was the lay of the land and its orientation to the predominant incoming swell. The southeastern tip of Java sticks out like a hook, trapping the southerly Indian Ocean swells and funneling them into the surf spot. It also has an offshore submarine trench, which helps enhance the consistency of the surf. The waves in front of the surf camp are at least twice the size of Uluwatu on the nearby island of Bali, even though both coastlines face in exactly the same direction.

So it was a big shock to arrive and find minimal surf trickling into our most reliable surf location. My brother Victor and I knew it had to be flat sometime; surf everywhere else on the planet is like that. But when the days passing stretched into a whole week without waves, we began to worry. The arrival of a surf charter sailboat broke up the monotony of laying around in the tree houses carefully watching the horizon in hopes of another arrival: the forerunner sets of a new swell. These were the early days before surf forecasting became the enterprising science it is today. Other than taking a look out to sea, there was no way of knowing whether any surf was coming. Several Brazilian surfers had arranged for the boat charter and having a few extra berths, they allowed two Hawaiians to fill the empty space.

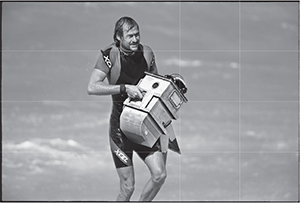

One was Don King. In between his junior and senior years on a water polo scholarship at Stanford University, Don came out to shoot photos in Bali and joined us for a ten-day run at G-Land. The surf, as usual, was magnificent and the place had the same effect on Don that it had on us: love at first sight. Several years later, living in Hawai’i and with his fame in water photography gaining momentum, Don was on assignment full-time as a staff photographer for Surfing magazine. Indonesia was the hot spot for surf during the months of April through October, and Don was there to film the action.

For this trip he had enlisted Mike Stewart. Mike’s career as one of the world’s leading boogie boarders was just around the corner ahead, but his water skills were already well developed. Both friends were like fish in the ocean. Even without fins they moved through the water with ease. Don regaled Mike with stories of great waves at the remote G-Land surf camp, and they had taken the extra berths on the chartered boat.

They heard we were on the beach and came ashore on the inflatable dinghy to say hello. The captain of the sailboat was a dour, stern taskmaster who took his work and his equipment very seriously. He drove the inflatable over the reef and stayed with it on the beach while Don and Mike tracked us down in our little tree house. None of us knew of any imminent surf, but we traded tales of great waves we had ridden here on past trips. Finally, one of the camp boys came to tell us the boat captain was getting impatient and wanted to leave before the tide got any lower. He need not have worried as we were in a full moon cycle of tides, the highest water of the entire month. Our friends informed us that the Brazilians had been giving the captain fits the entire voyage with their wild behavior. Don and Mike wanted to stay on his good side, so we all said goodbye for the moment.

The next day was no different: The surf remained flat. The offshore winds that normally would have combed the long walls into perfection howled through the trees and over the wave-barren reef. We lay in our tree house, reading and bored out of our minds, but without surf, there was little else to do. Victor has never been a patient man, and the long week of inactivity was wearing thin on him. To put it mildly, he was one grumpy person ready to snap at the slightest provocation.

Meanwhile back on the sailboat, the captain must have found some qualities he liked in Don and Mike because, contrary to his nature, he agreed that they could take his precious inflatable for a cruise. Equally bored out of their minds, the boys eagerly jumped into the little dinghy and fired up the outboard engine.

Up in the tree house, I happened to hear the faint whine of a two-stroke motor and glanced up from my book. When the tide is full on the big tide cycle, there is plenty of water over the reef. The small surf size meant the waves were insufficient to even break over the normal or most inside lineup. But over the shallow inner reef, the tiny swells were pushed upward and little waves were formed for a short distance before they again sank down into the deeper water closer to shore. Don and Mike were using the inflatable like a motorized surfboard and riding these miniscule waves. Back and forth they wove, trying to milk the longest ride possible out of the short-duration waves. When the wave they were on petered out, they would wheel the little boat around and race back to catch another one. It was the only surfing anyone had done for over a week, and they were having a blast.

The noise from the outboard was slightly irritating in the serene jungle setting, but they were having fun and it was harmless … or so it seemed. I just happened to look up as Don was driving back outside when another wave popped up right in front of them. Apparently he failed to warn Mike who was sitting up front on the opposite side. When Don suddenly turned to catch the wave Mike must not have been holding on and flew right off the boat. The loss of Mike as ballast greatly upset the delicate balance on the tiny inflatable and the result was the boat tipping the other way. This threw Don off the other side. I put my book down and sat up so I could see better.

The driverless boat completed the turn into the wave and toward shore. Without any weight in the boat, the brisk offshore winds lifted the bow until it was at an impossible angle and on the verge of going over backward. It was also racing at full throttle straight toward the beach. I sat up a little straighter to see where it would crash into the shoreline.

But, as the little boat came into the wind shadow near shore, caused by the thick jungle, the nose came back down into the water. There must have been a very slight tilt in the angle of the outboard’s tiller because the boat made a sweeping turn and was now headed straight back out to sea. Just when it looked like it would run into the little waves, the driverless boat made another big turn and was again racing back toward the beach. The wind got under the nose and put the little dinghy into the wheelie position it had assumed on the first lap. Inside the wind shadow of the trees, the bow dropped, and like before, the boat swept around and blazed back the other way.

“You need to see this,” I said to Victor who had his nose buried in his book.

Removing his reading glasses to look where I was pointing, he muttered, “What the heck?”

Meanwhile in a desperate effort to retake control of the lost boat running at full throttle before the captain on the sailboat realized what was going on, Don and Mike swam to intercept it. With the binoculars, Victor watched the action up close and gave me a blow-by-blow description.

“These idiots are going to kill themselves,” he exclaimed.

This did seem likely: There was that spinning prop on the outboard that would have shredded flesh and bone. The boys tried to grab at the speeding boat, but at the last moment had to hurl themselves out of the way of the slicing propeller. As the boat made another lap, Don and Mike tried again, but it was an impossibly dangerous feat.

Victor was enjoying himself for the first time in several days and kept the running commentary going for my benefit. We lost count of the laps and speculated that the engine would run out of gas. Meanwhile, the boat raced around its big oval course.

Finally, in an act of complete desperation, Don put himself directly in the boat’s path and made a flying leap as it came at him. Somehow he got a hold of the side. Through the binoculars, Victor’s glee at their predicament turned to horror as he could see Don was slowly sliding down the side, closer and closer to the spinning propeller. When it looked like the worst was about to happen, and Don clutching the side was about to slip under the stern where the racing outboard waited, it was suddenly over. By hanging on, Don had slowed the boat enough that Mike was able to chase it down. He managed to climb on, and just before it appeared Don was about to be filleted, Mike killed the motor.

We watched the boys pull themselves back aboard, restart the engine and very slowly motor back toward the mother ship, tails between their legs. The episode had energized Victor and brought him out of his funky mood. We laughed and laughed about it. The next day the surf finally came, and we were back in the money. We surfed our days away as usual, spending most of the daylight hours on our surfboards and limping back in at sunset to eat and fall into a deep sleep, and then do it all over again the following day.

On a recent trip with Don, I reminded him of the incident, and he just laughed and shook his head. Surfing is and always will be a series of close calls and near misses; danger always lurking, but the attraction never fades.

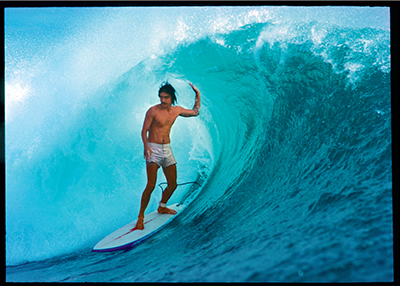

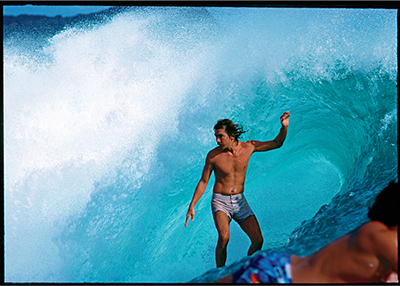

For any surfer, there is always one place that will challenge his skills and experience more than any other. For me, that place is G-Land. Photo: Art Brewer

b. GALLERY

Photo: Steve Wilkings

The Ala Moana Bowl was where the most progressive summertime surfing in Hawai’i went down. The surf leash indicates this was the later 1970s, before that there were many long swims to retrieve lost boards. Photos: Steve Wilkings

Reno Abellira and I shared many waves together through the many summer seasons at Ala Mo’. Photo: Steve Wilkings

A rogue’s gallery if ever there was one, this lineup from the mid-1970s included Eddie Aikau, Rory Russell, me, Larry Bertlemann, Michael Ho, and Reno Abellira. Photo: Dan Merkel

A clean swell from the northwest could produce some beautiful peaks with equally epic rights and lefts at the Pipeline. Photo: Jeff Divine

The photographer, Denjiro Sato, and I call this photo the banzai picture because of the arms raised in the traditional Japanese celebration of life. Photo: Denjiro Sato

Flippy Hoffman grills me on the technique to paddle out during a large, consistent swell at the Pipeline. Photo: Art Brewer

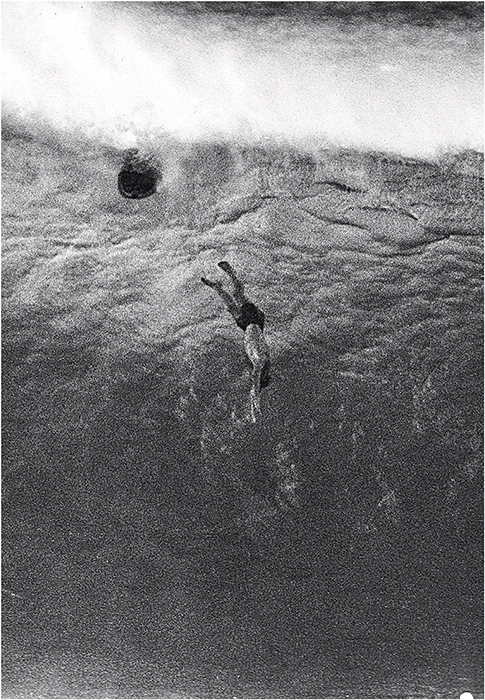

The price of not catching the wave at the Pipeline was costly, not something any surfer liked to pay more than once. Photo: Jeff Divine

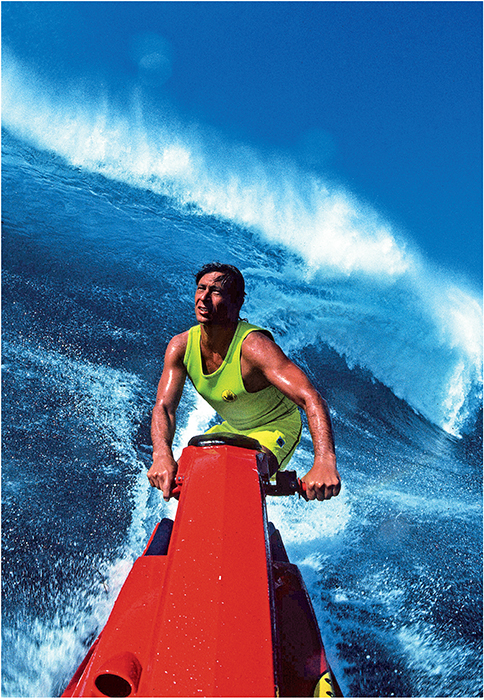

Herbie Fletcher and his souped-up Kawasaki pioneered the use of personal watercraft in big surf and laid the groundwork for tow-in surfing in the years ahead. Photo: Jeff Divine