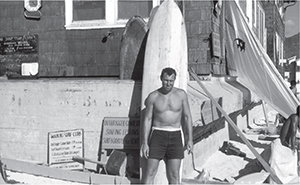

Big Wally

Walter, at the waikiki Surf Club, with a balsa board he made out of wood salvaged from a surplus world war ii life raft. the life rafts for ships used heavy wood, but the aircraft life rafts were made out of the lightest balsa and were ideal for surfboards … if one knew where to find them, and walter, of course, had it figured out. Photo: hoffman collection

Many surfers agree that the second best thing about surfing is talking about it afterward. As we tell and retell surf stories, waves grow ever more enormous and frightening, wipeouts ache immeasurably more each terrible time, and our heroes dwarf human scale. Often our stories so delight tellers and listeners alike that these epic tales become legends, and even approach the status of mythology.

Just as in tales of the Norse, the Greek, the Samurai, and in many more of the world’s cultures, at the center of each surfing fable stands the hero or heroine. This individual is extraordinarily brave, skillful, or funny. The surfing world is blessed with many characters to serve as models for these modern myths. A select few heroes gain the special status of icon. Attaining this exalted perch, surveying all of surfdom, arises from signature moves that render the particular hero unique amid the masses of the paddling humanity. Devotees to such a wily Odysseus will recite all of his legends from the epic to the mundane. Sycophants literally quiver in awe when granted an audience before the hero.

Those few individuals who attain such a following often have a follower or two who may feel an imperative to keep the legends alive. A teller of the tales rises to the call of duty by reciting the mythical deeds whenever possible. In my own small way, I feel an obligation to record at least some of the stories I have lived and heard. Let not my generation of surfers vanish quietly like spindrift on a clear offshore day. Better to raise our voices in unison, as Dylan Thomas urged, and to rage against the dying of the light.

The many thick layers of tales form like enamel around legendary pioneer Walter Hoffman. Hoffman’s broad influence during the early years of California surfing secures for him a knight’s nobility in the hierarchy of surf prestige. He was a stylish surfer who developed grace and skill in the all-but-empty breaks of post-World War II Southern California. Pursuing his dream in 1948, he advanced to Hawai’i, origin of the sport of chiefs.

The beach boys of Waikiki, masters of Hawaiian surfing and ambassadors of aloha, recognized Hoffman’s abilities and welcomed him to join among them. Hawaiian tradition dictates that a great surfer is always accepted with open arms into the ranks of local surfers. A Waikiki beachboy, even a haole from the coast, must have a nickname. Walter became ‘Wally,’ and graciously slid into “livin-on-a-easy.” When the waves were up, he surfed all day. When rich visitors brought food to the beach, he ate like a prince. Wally learned to play the ‘ukulele and to dance the hula. He sang golden summer notes in the beachboy chorus.

Wally surfed tandem so well that beach beauties competed to be his partner. An excellent canoe surfer, he was one of the first to return to California beaches with a Hawaiian outrigger. Only Lorrin ‘Whitey’ Harrison had a bigger canoe than Wally. He was one of first to pursue free-dive blue-water spearfishing, going after big tuna long before this became an international sport. He survived several close calls when a speared fish swam loops around him, wrapping Wally in the spear’s line to take him to the bottom in the fish’s dying spasms. He was first in at many of the premier diving locations in Baja in his legendary pursuit of the great Guadalupe grouper and the coveted giant jewfish. He bore early witness to California’s undersea gardens where, in his own words, “the bottom was red with lobsters.”

Walter’s innate business acumen also served him well. After investing fully the years of his youth in surfing and diving, he and his brother Philip settled in to work for their father Rube’s company, Hoffman Fabrics. Philip focused on selling to fabric retailers. Walter quickly recognized the market potential in the fledgling surf apparel industry. He supplied printed fabric designs and set cloth standards for most of the trunks, aloha shirts, and other woven garments of the American surfwear industry. Walter was also a financial flat-tracker. He reaped a vast personal fortune in investments by his uncannily shrewd ability to anticipate profit or loss.

Walter always loved dirt bikes. A racer at heart, he was at his best on the starting line of a desert race. He loved lining up handlebar to handlebar with racing legends like Dick Vick, Malcolm Smith, J. N. Roberts, and Dick Mann, as well as alongside friends and fellow surfer/racers Grubby Clark, Dave Rochlen, Rennie Yater, Phil Stubbs, Hobie Alter, Bruce Brown, and Jim Jenks.

Through the years Wally’s motorcycles were gleaming examples of brush-tuning and high standards of maintenance. His bikes were custom built to his own specifications for his daring riding style. He immersed himself in every aspect of dirt bike racing. He studied every move and all of the statistics. He became personally acquainted with many of the top racers, who often were equally honored to meet Walter.

He was a regular at the Friday night flat track races at Ascot Park in Gardena and a personal friend of J. C. Agajanian, promoter of the events and track owner. Walter would gather his friends every Friday afternoon at his home in Capo Beach, and then they made the trek to the speedway, where this particular Big Wally myth begins.

This would not be just any Friday night race. This was the once-in-a-season American Motorcycle Association half-mile Grand National. All the national number riders were there, racing for points and glory. The purse was less than an afterthought that Friday night. The favored nationally ranked racers breezed through their heat races on toward the main event, easily leaving behind the local fill-in riders.

Walter and his Dana Point cronies were all there, hollering the dead to dance. Surprisingly, the son of an old friend of Walter’s, who was attending UCLA, managed to locate Wally and the Dana Point crew. This was quite a feat in itself as the race was sold out and the stands were choked with howlers. The schoolboy’s father had long ago moved the family from California to Hawai’i to pursue a career in construction and a pastime in surfing … or maybe it was the other way around. The son had grown up on the North Shore of O’ahu, a local island boy; the youngster didn’t know many people on the mainland.

His father had suggested calling Walter, who was known for his Hawaiian-style hospitality. Walter immediately invited the lad to the races. Walter said that a ticket would be waiting at will call and described how the student could find the group. They always sat in the same place near the first turn after the start line.

Seated at last next to a red-faced, heavy-breathing Walter, the kid was a little uneasy. The area near the raceway he’d driven through to find parking was sketchy at best. Most of the race enthusiasts present, excluding Walter’s crew, were either motorcycle gang members, assorted motorheads, or otherwise didn’t fit any familiar profile in the experience of the kid from Hawai’i. Being a freshman college boy, he was the one who drew hard looks as he jostled his way through this foreign territory.

Notwithstanding the noisy, chaotic atmosphere, Walter observed the kid’s frayed nerves. In a gesture consistent with Big Wally’s simpatico nature, he draped a heavy sweaty arm over the youngster’s shoulder and yelled in his ear. “You got here just in time, they’re getting ready to start the main event. Let me tell you, this is the finest racing known to man.”

“You see those riders on the line out there?” Walter continued. “If they screw up, they go over the falls with a Harley. Guys get killed hitting the wall in this turn all the time. That’s why we always sit here. These are MEN.”

Walter had to shout to be heard as the noise level grew.

“You see that little guy, number 7, that’s Sammy Tanner. They call him the ‘Flying Flea.’ He weighs 125 pounds soaking wet, but his balls must weigh twenty-five pounds each. Jeez, is he something—these guys put it all on the line.”

The din rose as the racers found their places on the starting line. At the core of the sound were the revving engines, deep throbbing bass notes of 750cc Harley Davidson motors. Individual rhythms were set by each rider’s hand on his throttle. This cacophony of sounds crackled like electricity in the air around the track, stimulating the crowd to its feet as the noise level steadily intensified.

The crowd’s roar seemed to issue forth from the depths of a single living creature, born of age-old excitement, anticipating the coming spectacle. This was a modern chariot race. The feelings of these spectators were every bit as primal as the Romans felt at Circus Maximus.

Everyone in the stands was up and screaming as Walter yelled into the boy’s ear. “You’ve never seen anything like this. This is the finest. You know what it’s like? This is like … PIPELINE!”

The moment of urgency drew near as the flagman moved off to the side of the track. He still held the flag motionless to indicate the last seconds before he would drop it. The riders were absolutely focused on that flag, their engines at full roar, bursting to engage. Completely focused in turn on the riders, the crowd was on fire. The noise was near wholly full. Walter himself was in frenzy, short of breath and red of face. He yelled again, spittle flying.

“You’ve never seen anything like this. This is the finest. You know what it’s like? This is like … PIPELINE!”

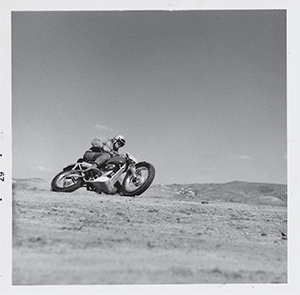

Photo: Hoffman collection

“This is like … BIG PIPELINE.”

Walter appeared crazed in this moment. The flagman held the flag up, ready to sweep it down. The riders were poised, intent. The bikes looked and sounded deadly.

“BIG … OUTSIDE … PIPELINE!” bellowed Wally.

The flag dropped, the bikes roared off the line quickly accelerating, thirty, forty, fifty, sixty, seventy, up to eighty miles per hour, handlebar to handlebar, flying into the first turn where Wally and the boys stood on their seats elbowing each other to get the best view.

Out on the track, the riders pitched their bikes sideways entering the turn, inside leg locked open at the knee, steel sole strapped to their left boots, foot down sliding, throttles pegged wide open. The pack was still tight, jockeying for the inside, or for any advantage to get ahead.

A daring rider hung it out, dove in front of the whole field, passing four or five bikes in one move, the finest moment. Walter was at the absolute zenith of moto ecstasy. His mind still frantically searched for that elusive last surf analogy to hold out the moment in perspective, so the college boy could fully grasp it.

The dirt rooster tails filled the air in the first turn. The view abruptly changed from head-on to going-away as the leaders made the turn. The bikes were all still sideways and bucking violently over the ruts in the track. The riders slid delicately on their steel shoes. It would be bad to catch a foot, to slide-out, or worse, to high-side in front of the pack. The oncoming bikes would chop the fallen rider into hamburger. In those last, most frenzied moments after the start, before the riders began to string out for the long twenty-four laps ahead, where the passes would still be exciting but more calculated, singular and never as tense as in the beginning of the race, it finally came to Wally. A maniacal gleam formed in his eyes, panting heavily, giggling out of control, his voice a strangled, barely intelligible shriek:

“BIG, OUTSIDE PIPELINE … WITH SHARKS!”

The steep drop at the Pipeline sets up the bottom turn that, if it is performed well, allows the surfer to exit the turn with more speed then he had going in. Photo: Jeff Divine