Uluwatu in 1975 was a surfing paradise with few people to share it with. today it still is paradise, and everyone knows it. Photo: Dana Edmunds

Tales of Indonesia

THE FIRST TIME TO BALI

I get a lot of credit for being a pioneer of the surf in Indonesia. I really don’t deserve it. If not for a good friend of mine, I would not have had the good fortune to arrive there so early as I did.

Jack McCoy and I had grown up surfing together during the early 1960s on O’ahu’s eastern coast near Aina Haina, Niu Valley, and Kuli’ou’ou. We traveled to Australia together for the 1971 World Surfing Championships as members of the Hawai’i State surf team.

We loved Australia. The place was spacious and inviting. The people were friendly and imbued with that particular essence of rugged individualism for which they’ve become justly famous. The surf exceeded our expectations. When it came time to leave, Jack calmly announced that he wasn’t coming. He decided to stay Down Under.

Well, I supposed, why not? It was a great place. We left and he stayed. Jack and I kept in touch. I began doing some business with my surfboard company in Australia, and we enjoyed catching up during those visits. Several years later, when professional surfing contests began to happen, Hawai’i and Australia were the two main venues. Australia became a regular stop on the surf circuit and a very agreeable one at that. In Australia, surfers were regarded as legitimate professional athletes. That was a big step up for us. At home, surfers were marginalized, regarded as outcasts who disdained the core values of the larger society and lacked any form of work ethic.

Jack perked my interest in going to Bali. He deserves most of the credit as one of the premier Indonesian surf pioneers. Jeff Hakman and I were staying with Jack down in Torquay for the annual Bells Beach Easter Surf Classic. The little beach town of Torquay is a cold, gloomy part of Victoria during Easter, but sometimes the surf can be pretty good.

Uluwatu in 1975 was a surfing paradise with few people to share it with. today it still is paradise, and everyone knows it. Photo: Dana Edmunds

Jack had a great health food restaurant he owned with a couple of friends. On the wall there was a black-and-white photograph that intrigued me from the moment I first saw it. It was just a small four-by-five print of a water shot Jack had taken, or so I thought.

Among his many talents, Jack is a first-class surf photographer and a formidable water cameraman. The picture was of Wayne Lynch up high in the lip of a sweet-looking left. In response to my eager questions, Jack revealed that the wave was indeed even better than the photo could show. It was at a place called Uluwatu on the exotic island of Bali. I found out later that it was not Jack who took the picture, but his film partner Dickie Hoole. They had bought a new Nikonos water camera in Singapore, and Dickie swam out their first day in the surf to give it a try. Surf photography is never as easy as it might seem. Out of twenty-four exposures, twenty-three were blurry, white-out total misses, and the twenty-fourth was almost another except in the upper right hand corner was the image of Wayne.

As a child I had a thing for Bali after seeing the movie South Pacific, where Bloody Mary sang a haunting song about a mysterious place called Bali Hai. I barely knew about the island, but as soon as Jack said “Bali,” I was certain I was going.

Jack and I went to work on getting Hakman excited about it. Eventually we got him to agree that after the next contest, the Coca-Cola Surfabout in Sydney, we would all go check it out. Jeff was not wholeheartedly enthusiastic about the place because when Jack related the story behind the photograph, there were some reasons for concern.

The year before, Jack, Wayne, and Nat Young went up there on the first Bali trip for all of them. The surf they found was great, but there were too many late nights, too much sunburn, a few hairy motorcycle crashes, and Wayne came down with malaria upon their return to Australia. Neither Wayne nor Nat wanted to go back again.

Jack, however, was a Hawai’i boy born and raised. He’d had no trouble acclimating to the steamy equatorial weather. The surf there had something that he hadn’t seen anywhere else. Jack broke out the Alby Falzon film Morning of the Earth, which had a section of Steve Cooney and Rusty Miller riding the long, winding left at Uluwatu. The waves looked terrific. Finally Jeff said OK.

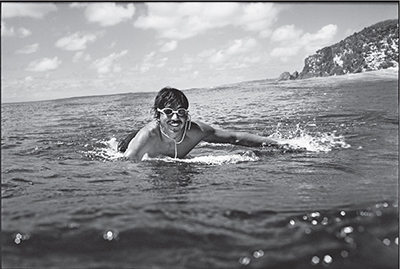

Sunshine is the only real enemy in Indo for anyone who likes to spend all day outdoors in the surf. Sunscreens for the skin got better but the eyes didn’t have that luxury. My first attempts at eye protection were swimming goggles. Photo: Dana Edmunds

The flight from Sydney to Denpasar is a relatively short one. With the long twelve-hour haul from Honolulu to Australia still fresh in our minds, the five-hour Bali flight was a breeze. With Jack as our amiable and well-seasoned guide, we were headed toward great waves in a warm place where surfing was still new.

We flew into our final approach to the island winging in from the south. Out the side windows we could see long lines of surf wrapping down a rocky headland. Even from that altitude the waves looked good. Later we learned that this headland was called the Bukit. The west side of it, where we would find Uluwatu, was all lefts. The other side had lots of rights, but the prevailing southerly winds blew onshore. That same wind was straight offshore on the Uluwatu side. Those wind-combed, beautifully peeling waves beckoned to us right from the start, while we were still flying in on the airplane.

After landing on a runway—built on the reef straight out into the surf—we taxied to the small terminal. When the crew opened the door, a blast of hot, humid air hit us like a breaking wave. We filed out as if we were passing through the portal to a dream. Beyond the airport, everywhere we looked were coconut trees, thousands of tall, beautifully shaped trunks capped with fronds that swayed gently in the tropic breeze.

Bali in 1974 had a sleepy village atmosphere. Everyone and everything moved at a languid pace. The tourist trade, consisting mainly of European travelers, had been directed to the east side of the island, near Sanur. Two main hotels, the Bali Beach and the Bali Hyatt, handled most of the island’s guests. There were excellent reefs in front of both hotels with fast, peeling rights, but the prevailing southerly trade winds blew onshore by late morning.

We were headed for the side of the island where the winds blew straight offshore. It was not far from the airport. Our destination was Kuta Beach, where small losmen, or bungalows, were intended for tourists who wanted to rough it a little. Compared to the international hotels of Sanur, the Kuta Beach accommodations were a bit primitive.

Jack had stayed at a place owned by a Mr. Kodja, who greeted him upon our arrival like a long-lost relative. The unexpected friendliness of the Balinese people was completely genuine. After five minutes, we were all treated as though we were family. Kodja’s losmen were nestled in a coconut grove a short walk from the beach. It was an idyllic spot, cool in the shade, quiet and peaceful.

I was stoked. We dropped our bags inside and headed to the beach for a look at the ocean. Our first sight was a wave crashing in the shorebreak. It was a perfect wave, swept clean by offshore winds. Following behind it was a seemingly endless procession of more just like it. The water was a clear blue-green and was beckoning us to jump right in.

Jack and I looked at each other, peeled off our shirts, and raced down to the water’s edge. We were like two kids loose in a candy store. We spent the next few minutes bodysurfing the thumping shore pound, pulling into spinning barrels, and squealing in complete delight.

“I told you, didn’t I?” Jack gloated.

“And I believed you too, didn’t I?” I replied.

We slipped into another bodysurf where I slid up on Jack’s back and rode the big man like a bodyboard. Giggling, we popped up together from the closeout.

“Come on, let’s get out, I’ve got to show you something better,” Jack announced as we waded in.

From higher up the beach he pointed out a wave breaking on an outer reef to our left. “See that? That’s a perfect left just like Ala Moana. I say we get our boards and paddle out, what do you think?”

The candy store was getting bigger all the time. We got our surfboards and walked about a half mile to where the crescent-shaped beach curved out toward the outer reefbreaks. There were a couple of hotels along the way, built just back from the beach; one called the Kartika Plaza looked like the biggest hotel in the area. Another smaller one that seemed to be about ten bungalows built around a courtyard was the Sunset Beach hotel. This one was right in front of the end break on the outer reef.

This outer reef ran for about a half mile before it intersected the airport’s reef runway. It was a long paddle out to the surf, but with nothing better to do and all day to do it, we jumped right in. As we got closer to the waves, they got bigger and better, and we paddled harder. No one was out. Jack informed us that this break was called Kuta Reef. It was indeed very much like our home break of Ala Moana; a long, peeling left with a big, hollow bowl about midway, then another whole inside section that tapered down and finally ran out of gas into the deep water channel.

It was heavenly and Jack kept saying, “I told you guys. Didn’t I tell you?”

He did and he was right. I was never so stoked to be anywhere in my life, and it was only the first afternoon. Our tickets were booked for a month’s stay, but Jack had assured us that we could extend them if we wanted.

The next day, Jack declared we would look for the real waves out toward the point we had flown over on our approach to the airport. Kuta Reef was just an appetizer.

Uluwatu was the main spot, and the waves there were quite a bit bigger. The candy store seemed to be turning into a shopping mall and I couldn’t wipe the grin off my face.

ULUWATU UNVEILED

The first time to Uluwatu began with aspirations of a well-planned, precisely executed Special Forces assault on the surf. It quickly deteriorated into a fool’s mission right from the start. It was our second day in Bali, and we had seen few other tourists where we stayed in the sleepy village of Kuta Beach. There were a couple of hippie backpacker types, some older Australian couples, but no other surfers. Jack McCoy, who was a veteran of another trip here a year earlier, knew he could hire transport for us down on bemo corner.

As I followed him on the dirt road fronting our losmen accommodations, he explained that a bemo was a little Datsun or Toyota pickup truck with a canopy built over the bed and bench seats. Private cars were scarce. The occasional taxi was a late 1950s or early 1960s Chevy, painstakingly maintained but most likely still running on the original factory parts. Engines wheezing, rods knocking, mufflers shot, shocks long worn away. The American vehicles were lovingly cared for and polished at every idle moment to a high gloss, but they were much too big and overweight for the narrow, pot-holed, mostly dirt tracks and lanes.

Denpasar and the more built-up Sanur tourist areas might have been different, but in Kuta Beach time seemed to stand still. The few private vehicles we noticed were motorbikes of miniscule engine displacement but kept immaculately clean even after years and many miles of use. The consummate family ride featured father sporting an antique motorcycle helmet offering little or no protection doing the driving; mother in traditional sarong, wearing a construction hard hat offering much less protection sat side-saddle behind; with a youngster or sometimes two squeezed in between. It made quite a picture but the lack of traffic and the sedate pace of … well, everything, kept their world safe.

The local mode of transportation was the bemo and the drive out to Ulu was slow and bumpy, but in every village all the kids would run out laughing and cheering us on. Photo: Dana Edmunds

Bemo Corner was a busy place. Three bemos, their drivers and assistants, plus a half dozen bystanders, made for a huge crowd. Jack, towering over everyone by a foot or two, spread them apart by his immense presence and high-volume talk-show-host voice.

“I want to hire bemo all day,” he boomed.

His dad, ‘Big Jack McCoy,’ was a much-listened-to radio personality in Hawai’i and young Jack had inherited the voice. Two of the drivers immediately found they were busy, but the third, with the oldest, most beat-up bemo perked up with interest. Jack and he put their heads together and exchanged a rapid-fire dialogue with much sign language, which I couldn’t follow but soon realized was a spirited negotiation. Jack came back to me, all smiles and shaka signs.

“Yeah man, we got him to take us out to Ulu and wait for us all day for 4,000 rups. He’s going to get gas and will come by our place in half an hour,” Jack informed me.

At 400 rupiah to the U.S. dollar and 600 to the Aussie dollar, I guessed ten bucks for a car all day was a pretty good deal. We went back to wake up Hakman, who was a late sleeper by nature, to tell him the good news and get our gear together.

We loaded our surfboards, some food, water, and ourselves into the back of our ride and off we went. It was early enough that most of the shops were still closed and the roads empty. The exhaust fumes blew directly into the back where we sat but we were too stoked to care. We passed the turnoff to the airport and were into new territory. At one point, shifting down into low gear, our little truck strained up a fairly steep hill. Looking out the back, a veritable sea of coconut trees stretched as far as we could see. On the left we had a brief view of a beautiful bay of jade-green water, with the airport runway on the far side and a wave breaking off the end of it. Jack informed us it was Jimbaran Bay and the high ground we were now on was the southern tip of Bali called the Bukit. At the end was an ancient temple inhabited by monkeys. There we would find the surf of Uluwatu. We had surfboards, we had food and water, we had plenty of stoke, and the waves were stacked to a horizon yet unseen.

We rolled through several little villages where everyone smiled and waved. We smiled and waved back. We saw a couple of other bemos headed the other way, their backs crammed with people. A few times we slowed down or stopped to let a man, or sometimes a very young boy, herd beautiful cows across the road using a long stick. The cows were golden-brown and white and looked more like beefy deer than bovines. No one seemed to be in a hurry except us.

Back then there weren’t many surfers around, and there were no signs or indications of where we would find Uluwatu. We drove to the end of the road and walked out to the deserted temple perched on the sharp point. It was a sheer drop to the water below, maybe 800 to 1,000 feet straight down. The temple must have been hundreds of years old and was deserted except for the occasional monkey flitting through the shrubbery. The surf looked great but disappeared out of sight around the point. Jack said he wanted to show us this place first, the southern-most tip of Bali, but that we needed to backtrack down the road to get to the surf spot of Uluwatu. An occasional track led off into the shrubs but they all looked the same. Jack had been here a year before but couldn’t remember which was the right track. Our driver and his assistant were no help, as neither had any idea what we were looking for nor was there anyone around to ask.

Finally we came to a track leading off the road that looked good to Jack. Our driver wanted to know when we would be back, and we guessed at about four to five hours. Except for us, the chirping of the birds, and bugs, there wasn’t anything else. We looked at Jack, shrugged our shoulders, grabbed our gear, and started down the track. The terrain was rugged limestone, full of hills and gullies, and the track was steep, crooked, and rough. It was a single track bordered with a thorny cactus-like plant that grew like a vine. We just followed where the track led. Up and down it went, back and forth, never in a straight line for very long, if ever. The thick walls of thorns didn’t allow much view, but the track seemed to be going somewhere. We came to an intersection and debated which turn to take.

Figuring the main road we came in on was more or less parallel to the coastline, we decided we needed to move at right angles to that. But the trail had twisted so much before the intersection it was hard to tell which way that was. We chose one and moved off. Soon we came to another trail crossing; again, neither way seemed headed toward the ocean. We took another guess and continued on. Before long it became apparent that we were headed back toward the road so we backtracked to the intersection and took the other way. After following this track for a while, it didn’t seem to be going where we wanted either.

Jeff climbed a nearby tree to get his bearings. It was a small tree, but I climbed up behind him. From this elevated view we could see the ocean in the distance and clambered back down with enthusiasm. Suddenly Jeff let out a screech, lifted up his shirt, searched himself, and plucked off a tiny, black ant. Then one bit me rather painfully, I peeled off my tee shirt and Jack jumped in to help us brush the ants off. Jeff held one of the tiny creatures up between his fingers, exclaiming, “How can such a small ant have such a large bite?”

This was our introduction to the insect life of Indonesia, a study that would fascinate us over the next twenty-five years of discovering and marveling at the many strange types.

Knowing which way the ocean was didn’t seem to be much help, as the trail wouldn’t head that direction. I had the idea that we should breach the thorny trail boundary and cross-country it. This met with the approval of both Jack and Jeff, since we sure weren’t getting any closer the way we were going. We walked along until we found a light place in the thorns, moved some aside and slipped through.

The other side was a huge, open space, like a pasture except without much grass. It was an empty field, so the going was easy, and we happily headed the way we wanted to go. This didn’t last long, as we soon came to the end of the open area and met with another thorn wall. Finding an opening to get through was more difficult, but after breaking our way past the thorns, we were on another track headed somewhere, but not toward the ocean.

We had been walking for over an hour and a half, and were hot, sweaty, antbitten, and out of patience. Going back wasn’t an option either; we had to admit we were lost. Just when it seemed like we might start going for each other’s throats, we heard someone coming. Around the corner came three surfers who looked like they knew where they were going. Introductions made, we found ourselves with three Maui boys, brothers Mike and Bill Boyum and Fred Haywood. It was a chance beginning to a lifelong friendship and many shared adventures.

Finally, with the new leadership, we arrived at the cliff overlooking the waves. It was as magnificent a sight as any surfer could behold. Perfect lines swept by clean offshore winds rolled in, peaked up and peeled off, occasionally hollowing out, spitting spray and continuing to peel off further. Jeff, Jack, and I blinked our eyes, blinked again, looked back, and realized we weren’t seeing things. This was real and except for Mike, Bill, and Fred, there wasn’t another soul around. We had just walked up to the gateway of paradise.

We followed the Maui boys down a makeshift ladder into a sea cave. In contrast to the searing temperature up above, it was refreshingly cool. The sand was coarse and clean. Mike had a Balinese boy who worked for him carrying an Igloo cooler jug. He brought it down the ladder and handed it over to Mike who beckoned us over to take a swig.

“Fresh pressed cane juice with lime,” he explained.

It was ice cold and delicious. There were some white things floating in the juice that he said were mangosteen. They were even tastier. We left our shoes and gear with the boy, whose name was Ketut, followed our new guides’ lead, and paddled out the cave entrance.

When we burst out into the sunlight, a sight right out of the best wet dream greeted us. As great as the waves looked from up above, they were even better up close. The surf was awesome. Punching through the inside whitewater, we timed our paddle out and slipped through the surfline. Outside we could see a wedging peak that looked like a nice beginning to a long, fast peeling wall.

Bubbling with barely contained excitement, I stroked out toward the peak, saw one swinging wide, paddled to intersect it, and dropped in. It was a steep takeoff, but the wave face was so clean and beautifully textured by the light offshore winds that I could have made it with my eyes closed. I stalled my turn, timing it to slip under the pitching lip, and tucked into my first tube at Uluwatu. A feeling of complete satisfaction washed over me as the wave curled around me. A smile spread across my face and I let out an unrestrained hoot. I knew this was some kind of surf heaven—and I was only on the first part of my first wave here.

We surfed hard for the next several hours. The sets were consistent with more than plenty of waves for everyone. It was a steady five to six feet with an eight-foot set steaming in on a regular basis every third or fourth set. The peak shifted around but bowled nicely, allowing a perfect backdoor setup right off the takeoff; then it was a race down the line as far as we wanted to paddle back out.

Eventually the tide began to go out, and the waves went into a transition mode, still good but not as defined in the peak takeoff. The Maui boys suggested we go into the beach and rest a little, let the tide go out, and come back out later. Ketut had brought our gear around to the front beach where there were some little caves at the base of the tall cliff offering cool shade. We crawled in, drank more of Mike’s cane juice, and tried to close our eyes.

They wouldn’t close, or if they did, images of perfectly peeling waves reeled off behind our eyelids. An hour later the tide had dropped dramatically, exposing the reef all the way out to where we had been surfing. Some local villagers in their bare feet walked out and began poking around the dry reef. It seemed the lower the tide got, the better the waves became. The takeoff seemed to be farther down the line from where we had surfed at the higher tide. It was an unusual wave that started small and then grew as it peeled down the line.

We picked our way over the dry reef carefully so as not to slice up our bare feet. Not far from the edge, the wave stood up, crashed over, then quickly died down to a gurgle where we stood not thirty feet away. It was the most amazing thing; the wave was powerful and hollow where it broke but dissipated down to nothing in a short distance. But getting to it was going to be tricky without getting our bare feet all cut up on the reef.

I noticed some cracks in the reef that seemed to lead out and were deeper. I put my surfboard in one with the fin up, carefully lay on it, keeping my full weight off by pressing down on the reef with my hands. When the surge washed in underneath, it floated my board, and I was able to ride back out with it. As soon as it was deep enough to paddle, I could make better speed and left the others behind doing their rock dance. Eventually there was deep enough water below me that I could roll my board over the right way and paddle full stroke. The rollover was a maneuver that I had down pat, having practiced many times during long waits in the lineup. I could do it in a flash without even getting off the board. Before long, I was in position to catch a wave while the others were still inching their way on dry reef.

A wave about four feet came toward me and looked good. The takeoff was easy, and I flicked a turn up onto the wall. The wave stretched out ahead of me as I raced it down the line. It seemed to grow not only in height but also in girth. I could see a section looming ahead of me that was twice as big as where I had first caught the wave. With good speed and a good line, I flew into the backdoor of the section and found myself deep inside a serious tunnel. A few more pumps and I shot out the other end, easing over the top as yet another even bigger section loomed ahead.

My heart was pounding, my breathing rapid, with both increasing when I saw the next wave. I put my head down and paddled hard to get out of the way of a full-on eight-foot, top-to-bottom, thick barrel. Angling for the shoulder with a good head of steam, I slipped around the wave but not before I had a chance to look deep within its bowels. I saw that it was hollow and clean enough to ride thirty feet back in the barrel. I was shaking like I had a fever, realizing how lightly I had taken my first wave. I had to be careful pulling into these thick inside waves as they broke very hard in very shallow water.

Fred Haywood was on the third wave. He had made it out pretty quick, maybe his feet were toughened by the sharp, low-tide Shark Pit reef in Lahaina, Maui. Riding backside, he approached the heavy inside section I had backdoored a few waves earlier. His wave was much bigger than mine. As I sat up to watch how he planned to negotiate this difficult section, he hit his turn perfectly and projected high on the wall just as the whole wave threw out over his head. Bent over at the waist, he eased a turn back down, somehow held his edge, and blew out of a tunnel big enough for our bemo to fit inside.

We named the inside section the Racetrack that day because it was exactly that, with high-speed, full-throttle runs that you raced to win or die on the razor-like reef waiting below. To this day, I remember pulling into a backdoor that I was watching break three sections ahead, ducking late into the first one as the second one was already pitching over, and seeing the third section in the distance getting ready to throw. Somehow I slipped through all of them and squirted out safe and sound.

The surfboards we brought to Bali that first trip were our contest boards for Australian events at Bells Beach and the North Sydney breaks. I had a 7’8” diamond tail, a 7’4” wing swallow-tail, and a 6’8” that I only remember as wide, thick, and fat. The 7’8” was too long and didn’t get much use. The 7’4” was the best size for what we were riding, but not one of my boards worked as well as I wanted. I got so frustrated with the 7’4” that I brought it back to Kuta one day, took a Surform tool, shaved off the wings, and reglassed over the bare foam. At the end of our trip, I gave it to Kim ‘The Fly’ Bradley of Avalon who was with us in Bali. I never wanted to see that piece of crap again. Kim hung on to the board, and recently Jack acquired it, showing it to me last winter on the North Shore.

Jeff’s boards didn’t work any better, and he ended up riding a board I had made for Jack in Torquay right before we left on the trip. Jack is a big man, so the 74” I built was a big board. But Jeff liked it and rode it every day. Able to knee paddle because of all the flotation, he had the added advantage of seeing the sets first. One time he also spotted something swimming toward us. As I looked where he was pointing, we both realized at the same time that it was a huge sea snake.

We both turned and bolted for shore, paddling right through the Maui boys sitting further inside. They didn’t bother to ask what we were running away from, they just turned and joined our flight, all of us knocking each other over trying to get away. Of course, the commotion we made trying to escape chased the snake away but we didn’t know that.

This trip was the first time that Jeff and I had worn surf leashes; they took some getting used to. They had been around for several years, but I guess we were old school and felt we didn’t need them. The rocky shoreline of Uluwatu at high tide was death on lost surfboards. Everyone else used a leash so Jeff and I gave it a go. The leashes of the day were black surgical tubing with a length of nylon inside. The theory was that the tubing would stretch out until it reached the length of the nylon, stopping the board from going any further, then rebounding it back to the surfer. The only trouble was that the waves at Ulu didn’t stop pulling when they reached the end of the cord inside, and they easily snapped the nylon. The wave kept pulling, stretching the rubber tubing to the thickness of a rubber band, at which point the rubber broke, or worse, it recoiled the board back like a rocket.

Unless the surfer was aware of this and ready for it when it happened, he would surface after getting tumbled by the wave to find his board flying back at his head. If he was lucky he might get his hand up in time to stop it. If not, he could get nailed right in the face. I fell off my board a lot so I had to put up with all the crap that went with using a leash. Jeff, on the other hand, gave up on the leash and concentrated on never losing his board. The only time he lost it was one time when Mike Boyum bailed off right in front of him and it was either let go or get nailed by Mike’s board. The attitude was different back then. When someone lost his surfboard, the guy riding the next wave surfed in and retrieved it.

I loved everything about Bali—the surf most of all—but the people were special too. I think the Dutch realized that when they colonized the region because they left Bali much as they found it while exploiting the heck out of Java and Sumatra.

Uluwatu was a world-class surf spot. Jeff and I would go out there four or five days in a row until its intensity just wore us out, then we would stay in Kuta for a few days surfing a much tamer Kuta Reef. A day or two of that and we would long for the power, the size, and the sheer magnitude of Ulu. We got a little motorbike; I would drive while Jeff held both boards behind me. Often we would be the only ones there.

Boyum lived right across the street from where we stayed, and we would try to get him to go out too, but Ulu was a heavy place. Nobody wanted it too much. The days we wouldn’t go out there weren’t because of a lack of surf; it was just a lack of motivation on our part. We were weary from all that surf. Jeff would sleep all day long on those days. It seemed the surf never stopped. Ulu was never less than six feet for the entire six weeks. It was utterly relentless. We would give it a miss just to come down from the high energy. By contrast, the people and the pace of life in Bali were languid.

There was a period in my life—the previous six or seven years—when I had no desire to be anywhere else than the Ala Moana parking lot during the summer season. Missing a south swell at the Bowl was an anathema to me until I went to Bali. Then all I wanted to do was go home, work, make some money and new surfboards, and get back to that idyllic island as quickly as I could.

Life is quite a journey; we find something we like and immediately build a fence around it to keep it the same. Then something else comes along, and we are over that fence in a flash with hardly a look back, chasing off after some other pipe dream.

d. GALLERY

A typical Indo local, the deadly poisonous coral sea snake. Photo: Dana Edmunds

Photo: Dana Edmunds

Wayan, my board carrier, waited for me each day with a patience I could only envy. Photo: Dana Edmunds

In the early days before it became known, Uluwatu was as close to heaven as a surfer could get. Photo: Dana Edmunds

The children in Bali were as beautiful as the waves, happy and smiling at all times. Photo: Dana Edmunds

Kuta Beach in 1974 was a lot different than it is today, but the waves remain the same: perfect. Photo: Dana Edmunds

A bottom turn at Uluwatu, before anyone had any ideas of building hotels on the hill in the background. Photo: Dana Edmunds

Photo: Jeff Divine

Enjoying the ambiance of a luxury beachfront suite at the G-Land surf camp–just 10 steps from the water–with Sidesy a Above nd Hosko. Photo: Art Brewer

Mike Boyum, who had the vision to create the first surf camp and see it through the headaches of getting it going, walks in after a long surf session. Photo: Don King

Having board carriers at Uluwatu allowed us to jog in to the beach for a pre-surf warm-up. They would carry our boards for twenty-five cents each way; most used what they earned as start-up capital for bigger business ventures. Photo: Dana Edmunds

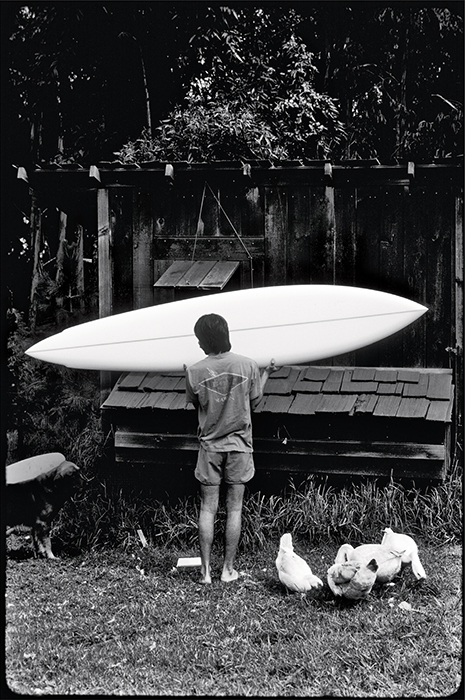

The shape of a big-wave board in 1975, standing just outside my shaping room next to the chicken coop in Olinda, Maui. Photo: Dana Edmunds