Schubert’s Kosegarten Settings of 1815: A Forgotten Liederspiel

MORTEN SOLVIK

In 1815 Franz Schubert composed twenty vocal works to poems by Gotthard Ludwig Kosegarten. This in itself is not a remarkable observation about a time period in which the composer produced an enormous number of Lieder, at least 138 in that year alone. But there is something unique about these works that has, until recently, been overlooked by music historians: collectively they share both a clearly constructed plot and musical devices that connect them into a coherent whole, suggesting the rather surprising conclusion that the songs belong together as a unified set, even as a type of cycle. Although some of the research presented here is known to specialists, the major points of evidence that support such an argument have yet to reach a wider audience.1 The following is an account of that discovery, a summary of the pieces of the puzzle as they came to light and how they fit together.

Manuscripts and Statistical Anomalies

The first indication that Schubert’s Kosegarten settings might form a unique collection of songs emerged quite by accident. In the course of conducting a broad survey of Schubert’s song manuscripts and working methods I decided to put together a statistical overview of the sources to all of Schubert’s surviving Lieder, some 625 in all. The method of cataloging relied on the three fundamental types of song manuscripts widely used in Schubert studies: sketches, rough drafts, and fair copies. Sketches (Entwürfe) are incomplete renderings of songs, either in the extent of melodic material or accompaniment that Schubert put to paper or, though they appear to be fully scored songs, only a portion survives. This latter type is more properly called a “torso”; approximately 8 percent of Schubert’s songs have a manuscript in this category. Rough drafts (erste Niederschriften) are completely rendered songs that are performable but have a hasty appearance and often contain corrections; this is by far the largest group, with about 54 percent of his songs represented. Fair copies (Reinschriften) are carefully prepared presentation copies of songs that Schubert wrote out in a clean, careful hand; this is a much smaller group, about 23 percent. There is also a fourth category that is often overlooked: songs for which we have no manuscripts in Schubert’s hand; this accounts for a surprisingly large number of works, 142 in all, or 23 percent of his songs.2

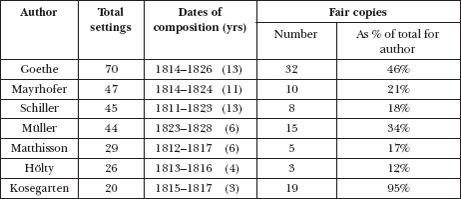

I was specifically looking for groupings within these three main types of manuscript, especially among the fair copies, relationships that might reflect unknown larger-scale organizations of songs. The documentation of Schubert’s life is so incomplete that it did not seem implausible to speculate that even today some of his musical projects may have been left unnoticed in the historical record. The information at first seemed haphazard, but the survey started suggesting some patterns when I began matching the percentages given above with poets whose works Schubert had set. During the course of his short life the composer turned to texts by 98 authors. The vast majority of these writers (83) were set fewer than ten times, and only seven were set twenty or more times, as can be seen in Table 1. The large number of works set to Goethe, Mayrhofer, and Schiller reflects an ongoing engagement with these poets’ works throughout Schubert’s composing career, as can be seen in the dates of composition. For Müller the concentration centered on his last years; Matthisson, Hölty, and Kosegarten held Schubert’s interest only in his highly productive early period.

Table 1. Schubert’s Most Frequently Set Authors of Lied Texts

These numbers speak for Schubert’s sometimes shifting literary taste, but—as already intimated—there is yet another way to measure their importance in his output: by examining the number of fair copies he produced for each. Fair copies required more time to prepare than rough drafts and were usually put together for a particular reason. These were the patterns I was looking for, and I could largely explain the results. In 1816 Schubert planned to bring out a series of volumes of German songs for distribution and publication. The first two volumes contained a total of 24 songs by Goethe but was met with rejection by the great poet and the project was called off.3 Fair copies of Mayrhofer settings over the years make sense, as he was a close friend of the composer. The Müller fair copies were compiled in the preparation of Winterreise.4 But what was the motivation for the abundance of Kosegarten in fair copy, second only to Goethe? This anomaly was even more glaring considering that Schubert copied out virtually every Kosegarten setting he ever wrote (95 percent, last column). No poet—not even Goethe—came close to this type of treatment. A glance at the numbers, then, suggests a short but intense engagement with this writer that may have led to the production of a collection of fair copies. An odd conclusion, given that the research on Schubert’s Kosegarten songs suggested no such large-scale project.

Piqued by this observation, my thoughts eventually moved from statistics to a consideration of what might explain the anomaly. Curious, but with no expectations, I started examining the evidence. The more I looked, the more I found, and as one clue led to the next it became increasingly obvious that something important was emerging from the data, a conclusion that seemed too significant to have remained hidden all this time: that the Kosegarten songs constituted a cycle. In the months that followed it was necessary to test the veracity of such a possibility, but the more I shook the foundations of this notion, the more the pieces fell into place.

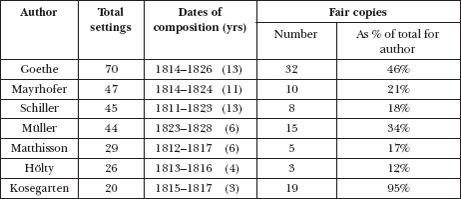

The logical place to begin an investigation was with the actual autograph scores. This in itself presented some difficulties, since making sense of the fair copies also required understanding the rough drafts on which they were based. This doubled the number of manuscripts that had to be considered from 11 to 22. A further complication was that, of these 22 documents, 14 were held in public archives in Austria, Germany, the UK, and the United States, 6 were in private collections in unknown locations, and 2 had disappeared entirely.5 It would be no small task simply gathering the information. Nevertheless, work progressed and a number of important observations came to light. The first concerned the dating of the manuscripts. If the fair copies had been compiled as a set, it would make most sense if this process had been undertaken for all of the songs at about the same time and after all of the rough drafts were finished. The dating of the rough drafts was largely unproblematic, as in most cases Schubert himself provided this information in marginal annotations. A look at the dates of these drafts (Table 2) reveals the remarkable intensity of the output of these songs, most produced in conjunction with other Kosegarten settings over only a day or two. After producing thirteen such songs over the course of roughly the month of July (including five Kosegarten songs on 7–8 July and five on 25–27 July), Schubert stopped until three months later, when, on a single day, 19 October, he wrote the remaining seven.

Table 2. The Rough Drafts to Schubert’s 1815 Kosegarten Settings, by Date

Dates are noted by Schubert on the manuscript except for those given in brackets or parentheses; those in square brackets are taken from the Witteczek-Spaun Collection (A-Wgm) as given in the Deutsch Catalogue, and the date in parentheses is inferred from a dated composition on the same leaf. The sigla shown in the Rough Draft column stem from RISM, the international index for music sources.

Figure 1. Cutting and folding of paper into a bifolio.

Establishing the dates of the fair copies proved far more elusive. Schubert merely indicated the work’s title on these documents. Solving this dilemma required turning to an arcane branch of musical research: paper types. Understanding this method of dating requires some knowledge of paper manufacturing in Schubert’s day. The process involved dissolving cotton fiber in a chemical mixture that broke down the bonds between the strands of the material into a gooey broth. The papermaker then needed a large porous screen made of metal wire arranged in a crisscross pattern and held in place by a wooden frame around the perimeter. The screen was first dipped into the mixture and then, while being held flat, carefully lifted out of the vat. As the liquid ran through the screen and over the edges, the cotton would immediately start to re-bond in a flat layer on top of the screen. The screen with the material forming on it would be pressed to free up excess water, the wet paper lifted out and laid on racks to dry. The large sheets were eventually cut, often along one axis, A, and then folded along another axis, B. The result was a “bifolio,” consisting of a folded sheet forming two pages and four sides (see Figure 1). If the paper was to be used for music notation, a device called a rastrum was employed to create the lines of the staves across the width of the page.

Fortunately for historians, paper production was a process that led to slight variations in the finished product. Paper mills commonly left their imprint on the paper by hand-weaving letters or symbols with copper wire into the dip screen; when the paper was pressed, water would form along the edges of these shapes and leave behind a gray shadow inside the paper that would become permanent. This “watermark” functioned as a type of stamp of origin that could be traced back to the manufacturer. What is more, as screens had to be replaced after extended use, the watermark wiring would usually differ ever so slightly from its predecessors, a natural consequence of the manual process involved. These slight discrepancies can be very important in isolating unique batches of paper. Other differences can be noted as well. The process of cutting the paper rendered the bifolios (and single leaves) oblong or upright in orientation. Different formats could be used for adding staff lines (usually 12 or 16 to a page), which in turn determined the dimensions on the page—a measurement known as the “total span,” from the top of the top staff to the bottom of the bottom staff. Thus Schubert’s manuscripts can be examined and categorized according to their physical characteristics. Since the composer tended to use up piles of paper in sequence, we can plausibly group works with the same traits to the same period of notation; and if several of these manuscripts are dated within a specific time frame, it is reasonable to assign undated works on the same paper type to the same period. Even if exact dates are not possible, these groupings at least allow us with certainty to exclude the possibility of manuscripts being written before their respective types appeared. 6

Applying this method to the Kosegarten manuscripts revealed three distinct types of paper (see Table 3). Type 1 appears in the Kosegarten songs set in June and July, Type 2 in the October songs, and Type 3 for all of the fair copies. By identifying dated manuscripts from each of these types, we can isolate the time period in which they were notated. For the dated rough drafts this is clear; for the undated fair copies, related documents suggest a time frame around April 1816.7 In other words, Schubert returned to all of the Kosegarten songs a number of months after the last of them had been composed in order to copy them out again in a clean hand. He did so on the same paper and likely within a short period of time.

Table 3. Kosegarten Settings, Paper Types, June 1815-April 1816

Four leaves of rough drafts, D221/233, 227, 230/231 and 313, have not been examined; the watermark to D236/237/238 is illegible; and D241 is notated on older paper. Fair copy leaves not examined: D236/237, 238, and 315/316. “Kiesling” and “Weilhartiz” refer to two paper manufacturers whose names appear on the respective watermarks. “Type” is used for illustrative purposes. For a more detailed treatment, see the critical edition of Franz Schubert’s works that uses a different classification: Types 1 and 2 listed here would be included in “Type II” and Type 3 in “Type I.”

It was beginning to look like the fair copies constituted a set of some sort, but the next question loomed even larger: Why were they compiled? The historical record provides no indication of a special occasion or a dedication that would explain such a major project or singular event. My investigation might have ended there, were it not for a curious development. In collating what I could of the fair copies, I noticed numbers in the lower left-hand corner on all of them, numbers that suggested a sequence from 1 to 20 that had nothing to do with the order of composition. Perhaps this could explain the existence of the fair copies. If so, the questions had shifted: Who had numbered them and for what purpose?

Cracking the Code

To answer these questions I needed to return to the manuscripts and take a closer look. In doing so, I found that, for my purposes, the most important information regarding the documents lay not in the composer’s own notations but rather in the markings left behind by others. Figure 2 shows the autograph of the rough draft of Schwangesang and divides the inscriptions found on the page into eleven elements: 1–6 stemming from Schubert and 7–11 attributable to later hands.

Schubert’s inscriptions:

1. The score is quite legible and represents a complete rendering of the work. The noteheads are mostly round and clearly positioned; the text underlay of the first verse is complete; dynamic markings, phrasings, and accents are also inserted. Corrections are infrequent, though revealing. In measure 4 the voice line half note on the third beat is changed to a fermata quarter to allow for the anacrusis to the next measure. Note that the piano right hand shows no such correction (quarter note fermata following long quarter rest), implying that the voice line was notated first. A similar change in the vocal line in measure 14 (last measure in system 3) demonstrates the same characteristic. A cross-out in measure 15 shows the composer simply finding a better voice-leading solution for the descending seventh in the piano left hand.

2. Schubert carefully wrote out and underlined the title toward the center of the page.

3. Schubert notes the exact day, month, and year of the manuscript, a common procedure during this period for this type of autograph, though it was a habit he would later largely abandon. Schubert wrote out eight Lieder that day, seven of them set to texts by Kosegarten.8

4, 5. Instrumentation (“S[ingstimme]” and “P[iano]F[orte]”) and clefs, tempo marking, time signature, and key signature are all provided at the beginning of the work with the key signature and clef repeated in each system. This is hardly an unusual procedure in a musical composition, yet not always the case in Schubert’s less polished song scores.

6. Schubert identifies the author of the text, “Koseg[arten],” at the end of the score and makes a note of how many additional verses not written out here should be appended to the strophic song (“6 Str[ophen]”).

Later inscriptions (not in Schubert’s hand):

7. A reference to a copy of the song “in Franz Schubert’s hand” listed as “[Number] 17” of Series “Abth[eilung]” IV.

8. A listing of songs from the “Repertorium” with similar titles, giving text, author, publishing information, publisher or plate number (“3523”) and location or catalogue number of these related manuscripts. Idens Schwanenlied, for instance, is listed as “No. 32, Series II.”

9. A number in the lower-left-hand corner in black ink (“24”).

10. A temporary plate number (“16755”), though not yet engraved (“noch nicht gest[ochen]”).

11. Various markings in various colors to the left of the title.

Though these marginalia at first seemed like little more than cryptic scribblings, curiosity drove me to wonder what they meant and who had gone to the trouble of adding this information. The references to plate numbers in items 8 and 10 indicated the work of someone in the publishing industry in the nineteenth century, but item 9 turned out to be far more puzzling. This number in the lower-left-hand corner turned up in dozens of manuscripts, yet clearly did not indicate plate numbers. Intriguing connections seemed to emerge between the seven Kosegarten rough drafts written on 19 October, with 23, 24, 26, 29, 30, 31, and 32 appearing in this position, whereas only two of the five songs from 7–8 July were even numbered (8 and 9), and the numbers from 25–27 July read 12, 13, 14, 1, and 2.

Figure 2. Inscriptions on rough draft of Schwangesang (D318).

The key to understanding the mysterious numberings turned out to be not the numbers themselves but the references to them provided in item 7. In the case of this manuscript of Schwangesang, the annotator provides the following information, as mentioned above: “A copy (or fair copy [Reinschrift]) in Franz Schubert’s hand see 17 Series IV.” There is in fact a fair copy of this song, Schwangesang, in Schubert’s hand; see Figure 3. Fair copies such as this resemble the rough drafts, but a few differing features stand out. The musical notation is more carefully prepared, with rounder note heads; there are more musical performance indications, and usually no corrections. At the top of the page, Schubert merely indicated the title of the song; the author attribution (“Kosegarten”) and date (“comp[osed] 19/10 [1]815”) were added by the annotator mentioned above, as was most of the rest of the marginalia.

Figure 3. Fair copy of Schwangesang (D318).

The connection between the marginalia numberings on the rough draft and the fair copy of the same song now became obvious. In the lower-left corner of the fair copy stood the number “17,” as indicated in the annotation on the rough draft. What is more, this fair copy provided a cross-reference to the rough draft in a perfectly complementary fashion; it referred back to the other manuscript as follows: “Das ursprüngliche Manuscript vide Nr 24 Schubert’s Lieder mit Namensfertigung und Datum Abth. I” (The original manuscript see No. 24 of Schubert’s Lieder with signature and date Series I). Compare the numbers in the lower-left corners of both manuscripts along with the references in the marginalia along the bottom edge in Figures 2 and 3. Whoever made these markings was concerned about pointing out manuscripts of the same song. Oddly, the rough drafts and fair copies were assigned not the same but separate “series” designations. What is more, the number in the lower-left corner, though associated with a specific series, never appeared with its Roman numeral designation; this could only be derived from the autograph that referred to it. Thus the “17” on the fair copy appears with no Roman numeral next to it; the assignation of the fair copy to “Series IV” could only be determined by consulting its rough draft, where it states: “A copy (or fair copy [Reinschrift]) in Franz Schubert’s hand see 17 Series IV.” Likewise, the fair copy explains the “24” in the lower-left-hand corner of the rough draft: “The original manuscript see No. 24 of Schubert’s Lieder with signature and date Series I.”9

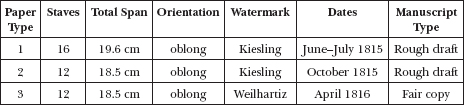

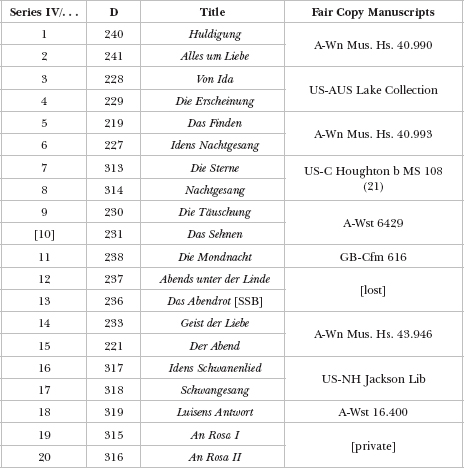

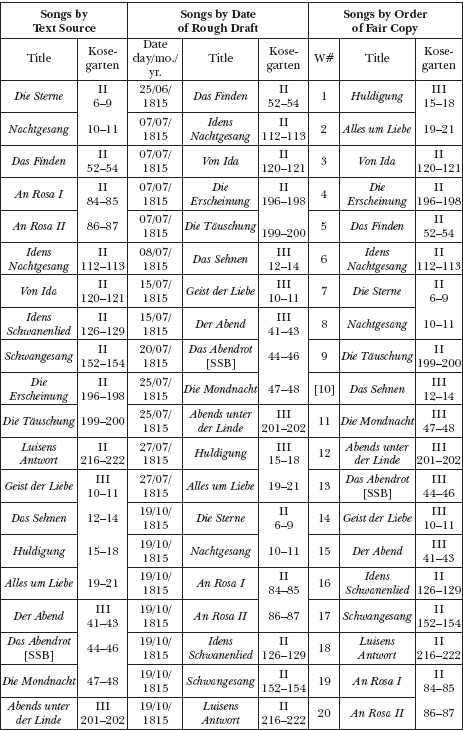

Having unlocked the secret of the numbers in the lower-left corner, it was now possible to organize the manuscripts by what looked like someone’s attempt to put the songs in order. The sequence that emerged on the rough drafts of the Kosegarten songs led to no significant patterns, but the case with the fair copies proved highly suggestive (see Table 4). By referring to the rough drafts of the 1815 Kosegarten settings, it was possible to determine that all twenty of the fair copies of these songs belonged to Series IV. In fact, Series IV would turn out to include only these twenty works. What is more, the twenty formed a set numbered consecutively from 1 to 20 that did not reflect the order of composition or sequences in any other series. But what criteria had determined these markings? Were these numberings arbitrary or did they reveal the sequence of songs as they had been grouped together as a set? It was necessary to identify who had entered these marginalia and the purpose for doing so.

Table 4. Kosegarten Fair Copies Arranged by Series IV

Note that the lower-left-hand corner of A-Wst 6429 verso is water damaged, precisely where the number “10” might otherwise be found; the recto leaf is clearly numbered “9.”

The most striking feature about these inscriptions is that nearly all of them were written in the same hand (type 7–9 and sometimes type 10).10 Fortunately, the writer left an important clue to his identity in another Schubert manuscript, where we find his signature: “Johann Wolf.”11 Aside from a note in an index by Alexander Weinmann, there is virtually nothing in the secondary literature about this person,12 yet in the manuscript collection at the Wienbibliothek we find two items that help shed some light on his murky biography.13 One is a letter from “Johann Wolf” written on 13 May 1848 to Adolf Bäuerle, editor of the Allgemeine Theaterzeitung.14 Wolf writes to correct a detail in a notice he had written for the paper concerning publications soon to appear at the publisher H. F. Müller, including several of his own works.15 The letter also contains a request to withhold certain information in lieu of the settlement of a dispute with Anton Diabelli over rights to a text. Thus the writer of the letter was obviously involved in the publishing business and also a composer. This aligns convincingly with the references to plate numbers and publishing firms in the marginalia of the Schubert song manuscripts. Significantly, the signature on this document matches exactly that found in the Schubert manuscript.

The second item at the Wienbibliothek is an album put together in honor of the publisher and music patron Karl Haslinger (1816–1868).16 This sumptuously bound volume compiled in 1862 contains dedications from over 120 friends and acquaintances, many of whom were leading figures of the music scene in Vienna in the mid-nineteenth century. Each contributor—including the likes of Simon Sechter, Carl Goldmark, Joachim Raff, and Johann Strauss—wrote a simple greeting, a short musical work or an incipit, signed his name, and provided a photograph of himself. On folio 65 we find a contribution by Johann Wolf with two short musical compositions, a signature, and a photo. Again, the signature (see Figure 4) exactly matches that found in the Schubert manuscript. The accompanying compositions confirm Wolf’s activities as a composer, but also reveal something more significant. The first of these two pieces provides indirect evidence that Wolf may have had privileged access to Schubert manuscripts. The work is a short vocal trio for men’s voices, titled Punschlied and set to a text by Schiller. Schubert also wrote a short vocal trio for men’s voices to the very same text (D277), a work that, significantly, was not published until 1892, thirty years after Wolf’s contribution to the Haslinger album.17 The publisher of the first edition of the Schubert part-song, as well as many of Wolf’s compositions, was C. A. Spina. A Viennese publisher who took over the firm established by Anton Diabelli in 1852,18 Spina brought out numerous first editions of Schubert Lieder in the 1860s. Wolf’s connection to this publisher is probably no coincidence: in all likelihood Spina hired Wolf to organize and annotate the Schubert manuscripts in question.19

Figure 4. Johann Wolf (1862).

Table 5a. An Overview of Wolf’s Manuscript Categories (Original German)

Abt. I: |

[Autograph] mit eigenhändiger Namensfertigung und Datum |

Abt. II: |

[Autograph] ohne Namensfertigung, jedoch mit Datum |

[Abt. III] |

[None] |

Abt. IV: |

Eine Copie (respect. Reinschrift) von Fr. Schubert’s Hand … aus der Sam[m]lung dessen Bruder Ferdinand herrührend |

Abt. V: |

Eine andere Bearbeitung |

Abt. VI: |

Copien von annäherungsweise Schubert’s Handschrift oder eines Verwandtens |

Abt. VII: |

Copie (von Ferdinand Schubert) … der Copien F. Schubert’scher Lieder |

Abt. VIII: |

Copien von verschiedenen Handschriften |

Several types of information provided in the margins of the Schubert manuscripts support this conclusion. In writing out his marginal comments, Wolf relied substantially on a catalogue known as the “Repertorium.” This catalogue must have contained detailed information about Schubert manuscripts such as titles, authors, dates of composition, and location, all of which Wolf dutifully notates. Several extant documents devoted to Schubert are labeled “Repertorium,”20 yet none provide the depth of information evident in the Wolf inscriptions. Instead, it seems likely that our scribe relied on a catalogue compiled by Anton Diabelli that is now lost, a probable scenario given Diabelli’s activities as a publisher and his unequaled access to Schubert manuscripts after the composer’s death.21 This suggestion is supported by yet another telling characteristic of the Wolf marginalia. Although publishers’ names (Leidesdorf, A. O. Witzendorf, etc.) often appear as part of information on publication, Wolf usually provides only the plate number if Diabelli or Spina published the song in question—a perfectly understandable procedure if Wolf was conducting an internal survey for the publishing house.

Comparing plate numbers and publication dates made it possible to determine with virtual certainty that Wolf added the inscriptions in the 1860s. Still, it was necessary to untangle the rationale behind the various designations, and particularly the numberings added to these pages as Wolf went about cataloguing the Schubert manuscripts. This, in turn, required reconstructing the problem he set out to solve. Wolf had the unenviable task of sifting through dozens if not hundreds of songs in manuscript, some published, some not, some dated, some signed, and so on. To make sense of this chaos, he had to design a system that provided him with the most important information in the most efficient manner. After culling through marginal inscriptions by Wolf on dozens of Schubert manuscripts it was possible to isolate seven categories that Wolf used repeatedly in dividing up the documents at his disposal (Table 5). 22

Table 5b. Overview of Wolf’s Manuscript Categories (Translation)

Series I: |

[Manuscript] with autograph signature and date |

Series II: |

[Manuscript] without autograph signature, but with date |

[Series III] |

[None] |

Series IV: |

A copy (or fair copy) in Franz Schubert’s hand … from the collection stemming from his brother Ferdinand |

Series V: |

Another version |

Series VI: |

Copies in a hand similar to Schubert or one related |

Series VII: |

Copies (by Ferdinand Schubert) … of the copies of Lieder by Franz Schubert |

Series VIII: |

Copies in various hands |

The scheme shows a clear progression from those manuscripts easiest to identify to those not even attributable to Schubert’s hand. Series I and II are ranked highest for being dated and sometimes also signed by the composer. This suggests that Wolf attempted as far as possible to order the manuscripts according to date of composition.23 Series III receives no mention in any of the manuscripts I have examined.24 As explained below, Series IV would turn out to be an exceptional group. Series V refers to reworkings of a previously existing Lied or Lied text. This category would make sense for someone trying to identify discrete Schubert songs, deciding to group later settings of the same text in a separate class.25 Series VI–VIII all refer to “copies”: VI in a hand closely resembling Schubert’s; VII apparently set aside for copies by his older brother Ferdinand; VIII copies by any other copyists obviously not Franz Schubert or his brother. Thus Wolf’s classification scheme was laid out according to chronological and orthographical considerations that allowed him to construct a rough overview of Schubert’s Lied compositions and, more important, file them in a fashion that made for easy retrieval. Since the marginalia frequently referred to published songs and songs of similar title, Wolf’s mission no doubt included identifying works that had not yet been printed. When publication decisions were made or when a particular song manuscript was needed, a quick glance at a catalogue would immediately provide its location. This would also explain the missing series numbers on the manuscripts themselves, since they would have been filed as physically separate groups. Once collated and archived the individual manuscripts could be found by going to the series, then searching ordinally for the number in the lower-left corner.

Series IV, the Kosegarten group, seems to have been compiled according to a rather different criterion, namely as “fair copies stemming from the collection (Sammlung) of Franz Schubert’s brother, Ferdinand.” The designation raises a puzzling question, for nearly all of the manuscripts Wolf surveyed had come from Ferdinand after the composer’s death. Many were published by Diabelli and Spina directly from Schubert’s “Nachlaß” (estate). The term “Sammlung,” then, refers to something rather more specific, a matter that emerges from the locution more clearly on second reading: not from Ferdinand Schubert’s collection, but rather from a collection in Ferdinand Schubert’s possession. This reading not only strongly supported other evidence that was coming into focus around the Kosegarten songs, but also suggested another dimension in interpreting Wolf’s numberings. If these manuscripts truly represented a self-contained collection, it would explain not only their isolated occurrence in Series IV but also the sequence Wolf assigned to them. Since all of these fair copy manuscripts lacked both date and signature, the reasonable assumption would be that Wolf numbered them as he found them gathered in the set.

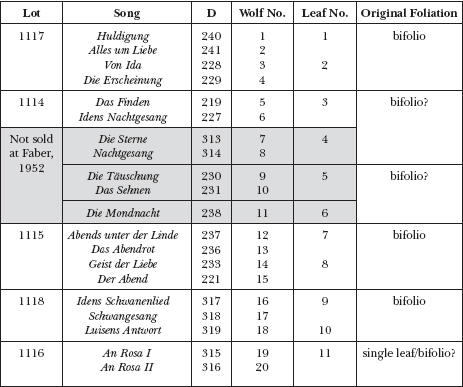

It was all the more important, then, to determine if the Kosegarten fair copies had at one time physically belonged together. The opaque formulation “collection” in the descriptions of Series IV and establishing that all the fair copies consisted of the same paper type supported this conclusion, but not definitively. The problem in attempting such a reconstruction lay in the fact that the surviving manuscripts were literally scattered around the world among numerous institutions and private collectors. Ironically, it was in tracing how the manuscripts came to be so dispersed that I found evidence for their common origin. In May 1952, the auction house Faber in Munich put five items on the block from the “Cranz Sammlung” (lot nos. 1114–1118). These consisted solely of fair copies of Schubert’s settings of Kosegarten. Fifteen of the twenty settings—all but three leaves—were included in the sale (see Table 6).

The identity of the seller of these manuscripts corroborates the connections already made with Wolf and the publisher Spina, for it was the Cranz family that finally took over Spina after it had been acquired by Friedrich Schreiber.26 The fact that so many pages of an earlier “collection” had remained together so long in the hands of the caretakers of materials handled by Wolf is itself suggestive, but the sale revealed even more important information. Lots 1117, 1115, and 1118 consisted of bifolios. Today these double leaves are separate manuscripts, but the auction in 1952 shows much of the original pagination of the set. Most striking is the alignment of the Wolf numbers with the leaves in the foliation, proof that Wolf’s sequence 1/2 (on two sides of the same leaf) was indeed followed by 3/4 on the leaf that was originally literally joined to it (the same applies, of course, to 12/13–14/15 and 16/17–18). Just why the pagination was destroyed is not difficult to determine. The reservation price for Lot 1115, a bifolio consisting of D237, 236, 233, and 221, was DM 2,400; five years later, that figure for a single leaf (D237, 236) came in at DM 2,500.27 It seems the owners more than doubled their money by literally cutting the bifolio in half.

Table 6. Kosegarten Fair Copy Manuscripts and Lots Sold at Karl & Faber, 1952

The lot numbers in the first column come from the Karl & Faber catalogue Handschriften Bücher + Autographen, 19–21 Mai 1952 (Munich, 1952), 148–49.

Wolf, we must remember, catalogued manuscripts in a state far more representative of the manner in which Schubert produced them, thus his work points to continuities now lost. Bifolios were still intact, sequences could be more readily reconstructed. To be sure, by the 1860s not all manuscripts were still in their original foliation; damage had already been done. For instance, Ferdinand Schubert gave away and sold manuscripts after his brother’s death, and publishers undoubtedly separated songs out of their original order. But Wolf was closer chronologically to the act of creation and very concerned about making sense of these documents. Since none of these manuscripts bear a date nor an author attribution, Wolf would have had no motive to intervene in the original foliation. As the paper type and auction sale of the fair copies strongly suggest, his numberings reliably reflect a group of manuscripts as he found them.28

Poet, Poems, and Plot

Although physical evidence suggested that Schubert may well have left behind a specially prepared collection of Kosegarten Lieder in fair copy, the manuscripts alone could not tell me what the composer intended with the set. To attribute this gathering of songs to Schubert’s artistic intention I had to probe much further into the collection and ask if its constituent parts likewise pointed to a large-scale construction. It made sense to begin with the text to see what may have attracted Schubert to these poems, where he found them, and how he integrated them into his song settings.

Gotthard Ludwig Kosegarten (1758–1818)29 was born in Mecklenburg but spent most of his life in Swedish Pomerania, a region in northern Germany that had come under the control of Gustav II in the 1630s. Educated in theology and classical philology, Kosegarten started his professional life as a private tutor for the well-to-do of Rügen, an island off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea, and became a preacher and eventually a professor in Greifswald, the commercial and administrative center of the region. He mingled with the educated classes and even taught such influential artists of the period as Philipp Otto Runge and Caspar David Friedrich.30 Kosegarten’s activities as a poet covered a wide range of lyric genres; his style was characterized by dramatic landscapes, Romantic longing, and occasional allusions to political struggle—themes typical of his generation. The turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars inspired in him a curious mixture of German nationalism and reverence for the French conqueror. Whereas many young nationalists initially saw an ally in Kosegarten, his subservience as an administrative official to the Napoleonic state and especially his speech in honor of Napoleon’s birthday in 1809 put him out of favor with progressive circles.31

Although he enjoyed a modest reputation in his own day, Kosegarten’s qualities as a writer were even then called into question. Friedrich Schiller, in a letter to Goethe from August 1797, writes:

I once told you that I had given Kosegarten my opinion [of him] and that I was eager to hear his response. He has now written to me and was very thankful for my frankness. Nevertheless, I can see there is no helping him, for accompanying the same letter was a publication announcement of his poems that only a lunatic [Verrückter] could have written. Some people are beyond help and God took this particular specimen and forged an iron plate around his brow.32

Figure 5. Portrait of Kosegarten.

Schubert nevertheless felt drawn to his work. Part of the reason for this no doubt lies in the tone of the texts Schubert chose. Kosegarten’s style shares a clear thematic and stylistic affinity with the works of Ossian, Klopstock, and Matthisson, all poets Schubert set during the same period.33

A look at Kosegarten’s publications reveals that the twenty poems Schubert set in 1815 were not printed as a separate set or isolated story. In all likelihood, Schubert found these texts in L. T. Kosegarten’s Poesieen. Neueste Auflage, a three-volume work dated “Berlin, 1803” (no publisher is given).34 The edition (Figure 6) demonstrates that Schubert was very selective, since the three-volume work contains a total of 144 poems.35 The verses show no strong pattern of coherence in the books, although, as is the case with the twenty Schubert selected, most tend to share a lyrical vein, strophic structure, clear scansion and rhyme schemes, and are almost all topically related to the idea of love lost and found followed by tragic demise.36 The texts also sometimes relate to one another through references to common names or events. This loosely structured, uncomplicated poetic source, though not profound in content, served Schubert with materials sufficiently pliable to craft together a larger structure.

Figure 6. Frontispiece to L. T. Kosegarten’s Poesieen: Neueste Auflage (Berlin, 1803), vol. 2.

A look at the arrangement of the poems in the printed collection compared to the Schubert settings demonstrates the point (see Table 7). In terms of continuity, the table shows numerous isolated settings as well as Schubert’s tendency to set consecutive poems (column 1), a tendency that also surfaces in the order in which they were written in rough draft (column 2). However, in the order suggested by Wolf’s fair copy numbering (column 3), the relationship to the original published source is reduced to a few paired texts. Far from the haphazard result one might expect from such a rearrangement, this departure from the Kosegarten publication demonstrates remarkable logic. In fact, the fair copy ordering strongly suggests an aesthetic intention operating independently of the poetic source. Through at times drastic intervention, it seems Schubert, perhaps working with his friends, re-formed the textual material into a sequence with clearly narrative tendencies.37

Not only do the texts collectively tell a story, they do so through the voices of three separate protagonists. Though only a few of the songs are definitively associated with a specific character—for instance, those with “Ida” in the title—it is not difficult to assign the roles as implied by the drama. The resulting story centers on a male suitor whose amorous attentions flit from one woman to the next (see Table 8). The feelings of the adventurer, Wilhelm, and two of his broken-hearted mistresses, Ida and Luisa, are presented in short strophic songs set within the typical Romantic conceits of longing and bliss. The first episode of the cycle opens with Wilhelm, who is infatuated with Elwina (song 1) but, it seems, is more enamored of love itself (2). Ida enters, despondent over a lover who has abandoned her (3). As she wanders through a grove of alderwood trees she appears to Wilhelm as if in a vision (4). The two meet; Wilhelm (5) then Ida (6) proclaim their happiness. The tryst continues as Wilhelm urges Ida to look to the stars where a far greater power resides (7). The liaison is short-lived as Wilhelm hears Luisa consoling herself under the night sky (8) and is lured away (second episode) (9). Ida succumbs to the longing that seems deemed to be her fate (10), while Wilhelm continues his escapades with a new mistress (11, 12). The cycle comes to a parenthetical caesura as all three characters sing a trio in praise of the evening (13). The third episode begins, once again, with Wilhelm praising love (14). At this point, Wilhelm’s description of the evening takes on an unaccustomedly dark tone (15). This unease proves prophetic as events take a tragic turn. The ever-distraught Ida sings of her torment (16) and decides to take her own life (17), while Luisa, Wilhelm’s beloved of the second episode, swears her fidelity even as Wilhelm betrays her (18). Wilhelm’s final appearance finds him pining for yet another woman, Rosa (the vision in the trio at the outset of episode three), who is absent (19) and who has also most likely taken her life in the face of her lover’s insincerity (20). Wilhelm is devastated, a victim of his own fickle heart.

Table 7. Schubert’s Arrangement of the Kosegarten Texts

The unfolding of a plot in Schubert’s arrangement of the texts can hardly represent the product of happenstance, especially as the resulting story echoes an archetype of the time. There is, admittedly, interpretation in assigning the characters to specific songs, but where the poetic titles do not directly reveal the identity of a figure, the situation and the content of the verses usually provide ample suggestion, such as the tryst between Wilhelm and Ida. Overall, there are three major episodes in this tale: the first focused on Wilhelm and Ida, the second introducing Luisa, and the third implying another lover, Rosa, while the women take their desperate leave.

Schubert’s Musical Setting

As surprising as it was to find a Romantic tale emerging from the sequence of songs arranged according to Wolf’s numbering of the documents supposedly in their original order, it was still necessary to determine whether any of this found expression in Schubert’s music. Only proof of the composer’s response to the structure of the story and an attempt to unify its disparate elements with conscious artistic devices could eliminate the chance of a possible, if highly unlikely accidental alignment of independent factors. A close reading of the Lieder does, in fact, reveal musical constructions that support the narrative outline and lend the twenty settings a strong sense of coherence.

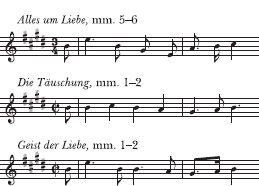

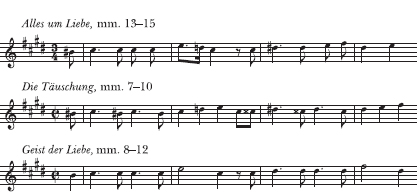

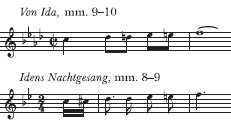

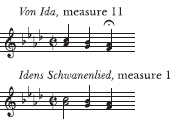

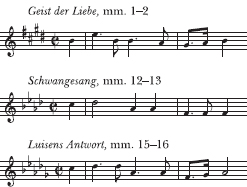

The first of these techniques involves motivic and other resemblances between songs identified with specific characters and moments in the unfolding of the drama. Schubert emphasizes the three-episode scheme in his composition by linking songs positioned just after the beginnings of each of these sections: Alles um Liebe (No. 2), Die Täuschung (No. 9), and Geist der Liebe (No. 14). All are homages to love in E major sung by the effusive protagonist, Wilhelm. Though composed over the span of several weeks, these three songs share obvious similarities. As can be seen in Example 1, all three of these songs open with virtually the same head motive, focusing on the E-major triad and finishing with an upward gesture in a dotted rhythm spanning a third. The subsequent melodic structure of these pivotal songs of the cycle displays the same close relationship (see Example 2). Note the persistence of dotted rhythms and the ascent that delineates first the third C♯–E then D♯–F♯ (see also mm. 9–13 of Huldigung). The relationship between Geist der Liebe and Alles um Liebe is even more profound (see Example 3). Here the melody (a1) and even the inner voices (b and c) are modeled on one another. The completion of the opening phrase in the piano (B–D♯–E) can be found at the end of the vocal line in Geist der Liebe: the last three notes (a2) spell out precisely this sequence, both answering Alles um Liebe and citing a motto  that occurs in many of the Lieder throughout the cycle.

that occurs in many of the Lieder throughout the cycle.

Table 8. Overview of the Kosegarten Lieder

Voice: W=Wilhelm, I=Ida, L=Luisa; names provided directly in texts to songs 3, 6, 7, 16, and 18.

Example 1. Head motive in Alles um Liebe, Die Täuschung, and Geist der Liebe.

Example 2. Melodic affinities between Alles um Liebe, Die Täuschung, and Geist der Liebe.

Ida’s songs, too, are linked by strong motivic affinities. Her first song, Von Ida, contains two gestures that will recur later. The first (Example 4) is a chromatic ascent from C to F (mm. 9–10) that both recalls the chromatic motion from  to

to  in Wilhelm’s Alles um Liebe (and following settings) and points to Idens Nachtgesang (mm. 7–9). Likewise, the descending thirds at the end of the song (measure 11) anticipate the opening of Idens Schwanenlied (measure 1); see Example 5. Note also that the idea of thirds spanning a melodic third (mm. 1–2) had already been introduced in Wilhelm’s Huldigung (measure 16) and will occur later in Die Erscheinung (measure 14).38

in Wilhelm’s Alles um Liebe (and following settings) and points to Idens Nachtgesang (mm. 7–9). Likewise, the descending thirds at the end of the song (measure 11) anticipate the opening of Idens Schwanenlied (measure 1); see Example 5. Note also that the idea of thirds spanning a melodic third (mm. 1–2) had already been introduced in Wilhelm’s Huldigung (measure 16) and will occur later in Die Erscheinung (measure 14).38

Consecutive songs linked by musical devices are common in the cycle as well. Wilhelm’s first two songs are tied together by voice leading at the end of the first (Huldigung, measure 20) that refers directly to the voice leading at the opening of the second (Alles um Liebe, mm. 1–2).39 Another example links Die Erscheinung and the following Das Finden with statements of “horn fifths,” a hunting sonority highly appropriate for Wilhelm’s successful pursuit of Ida (Example 6).

Example 3. Motivic references between Geist der Liebe and Alles um Liebe.

Example 4. Chromatic ascent in Ida’s songs.

Example 5. Descending thirds in Ida’s songs.

Example 6. Hunt motive in Wilhelm’s songs.

Similar, too, is the persistence of a dotted melody in Abends unter der Linde on C♯ at the word “Abendroth” (measure 9) heralding the opening of the following song, Das Abendrot (measure 1), with precisely the same gesture. In the case of Idens Schwanenlied and the following Schwangesang we find strong resemblances in the piano texture and voice line. After the opening gestures in the voice that both trace the F-minor triad, the voice line of Idens Schwanenlied (measure 1) can be found in the lowest line of the right hand in the piano accompaniment to Schwangesang (measure 1), whereas the lowest line of the piano accompaniment in Idens Schwanenlied is echoed by the left hand in Schwangesang. There are other similarities lurking here, but note especially the adherence to the same rhythmic patterns in both songs.

Portraying individual characters and linking consecutive songs lend a sense of sequential logic to the set as a whole, but Schubert goes further. Within the set we find subtle musical references to moments in the unfolding of the drama between the main protagonists. The tryst between Wilhelm and Ida, for instance, is depicted in three consecutive songs in B-flat major,40 the tonal midpoint between the respective realms of E major and F minor, the keys associated with Wilhelm and Ida, respectively (see Table 8).41 Soon thereafter, Wilhelm and Ida go their separate ways, or, to be more precise, Ida suffers (Das Sehnen) as Wilhelm finds himself in the throes of another romance (Die Mondnacht). In setting Ida’s complaint to a prominent descending tritone (Das Sehnen, mm. 7–8), Schubert anticipates the tragic demise of Idens Schwanenlied (tritone, measure 5) and an echo in Wilhelm’s Die Mondnacht (mm. 7, 11, 12, and 21).42 The text of the latter example is especially noteworthy in its use of an ingenious reversal of meaning. Ida’s lament of yearning (verse 1: “Fliesset, fliesset, Thränen!”) takes place not only at night, but also under the moon (verse 2). Wilhelm’s night song, on the other hand, forms a pendant to this song in a series of oppositions: he, too, sings to the moon, but does so out of joy; what is more, his adulation of the night quickly reveals itself as an homage to a distinctly earthly passion that expressly fulfills his longing: “Eines in andre gar versunken … Solches … kühlte das Sehnen, / Löschte die Wehmuth mit köstlichen Thränen” (“One sinking into the other … This … cooled the longing / Extinguished the sorrow with precious tears,” verse 3; see also “labende Thränen,” verse 2). Such blatantly sexual imagery leaves no doubt of the act being described, yet it accomplishes much more. The “precious tears” of Wilhelm’s fulfillment play ironically upon the “flowing tears” of Ida’s longing, a dialogue, as it were, over the distance that separates desire and consummation.

Schubert strikingly invokes motivic quotation in another section of the drama as well: toward the end of the set when Wilhelm’s forsaken mistresses take their leave. We literally hear the presence of the frivolous lover in the laments by Ida and Luisa as Schubert inserts Wilhelm’s signature head motive into their melodies (Example 7). Hearing echoes of Wilhelm’s enthusiasm as Ida openly greets death and as Luisa swears her faithfulness acts as a twist of the knife, an acerbic musical representation of fidelity in the face of betrayal and its tragic consequences.

Example 7. Remembering Wilhelm.

Figure 7. Rough draft of Alles um Liebe (D241).

That Schubert was aware of the significance of the head motive emerges in another context as well—in a telling alteration made during the composition of one of the Wilhelm songs. In the rough draft to Alles um Liebe (Figure 7) Schubert changed the vocal line in precisely the opening phrase, thus manipulating the musical idea in order to make patent its link with the other songs. As is clear from Example 8, had Schubert retained his first idea, the head motive would not have emerged. Instead, he crossed out the opening notes and reshaped the line into a descending triad followed by the upward dotted motion of a third, thus explicitly applying the head motive to the song.

In all, motivic references, voice leading, rhythmic constructions, textual continuities, an overall plot, a systematic use of key areas, and alterations in the musical scores lend the Kosegarten Lieder in the sequence suggested by Wolf’s numbering a compelling sense of unity and common intention. Such a preponderance of musical devices linking twenty songs together both in character depiction and dramatic interaction along with the manuscript evidence points to the conclusion that Schubert was constructing a set of Lieder intended as an integrated whole. But are we to understand this as a cycle? How were these twenty settings performed? And how does the set reflect the musical practice of the day?

Example 8. Alterations to the head motive in Alles um Liebe.

Songs, Cycles, and Society: The Liederspiel in Schubert’s World

The starting point for most considerations of Schubert’s song cycles is a set of twenty songs composed in 1823, Die schöne Müllerin. A look at Wilhelm Müller’s poems reveals that the plot of the cycle bears a striking similarity to the Kosegarten set but with the gender roles reversed: the story of a miller apprentice who falls in love with the daughter of the master miller, only to have his heart broken as she chooses another suitor; in the end he takes his life by drowning himself in a brook. In 1827, Schubert composed Winterreise to yet another set of poems by Müller, this time a more abstract tale: wandering through a winter landscape, the fraught character passes the places associated with a bygone love, seeking solace in an unforgiving world. Despite the common tragic tinge of love gone wrong, these later collections share a notable feature absent in the 1815 Kosegarten settings: the presentation of a highly personal telling of a story through the sole perspective of the protagonist, a solo voice with piano charting an inward journey. The performative and psychological framework in the late sets thus departs radically from the multi-character, essentially dramatic quality of the Kosegarten songs.

The Müller settings have made such a powerful impact on the notion of song cycle that we take for granted the overall features of both as a standard for the genre, though this does not reflect assumptions about collections of songs at the time. Schubert’s contemporaries were perplexed by Die schöne Müllerin. The set was not published as a single work but appeared in five volumes over the course of 1824. There is no known performance of the cycle during Schubert’s lifetime, and the premiere, sung by Julius Stockhausen, did not take place until 1856, twenty-eight years after the composer’s death.43 Perhaps not surprisingly, German Lied production of the 1820s and earlier demonstrates a very different approach from that of Schubert’s mature cycles. Songs could be published individually or, more commonly, in small groups. These songs often had little in common, but at times they were united by a theme or mood or even suggested a loosely narrative structure. The vast majority of Schubert’s Lieder appeared in print in precisely this fashion, and it is notable that publishers played a large role in determining how these works were released.

This is not to say that Schubert did not experiment with groupings of songs early in his career. Although not widely known, musical and codicological investigations of Schubert’s Lieder over the last few decades have turned up new evidence tying together what were once thought to be disparate musical compositions. Walther Dürr, for instance, has pointed to groupings of manuscripts in Schubert’s output such as the Selam Musenalmanach songs of 1815 that reveal an aesthetic affinity spanning seven songs.44 David Gramit has brought our attention to a “cluster of songs” centered on the Johann Mayrhofer settings from Heliopolis,45 and Richard Kramer has focused on “distant” connections between various songs spanning most of Schubert’s career.46 Nor should we forget such sets as the Don Gayseros songs (probably of 1816) or the Novalis Hymnen of 1819. Schubert’s 1815 settings of Kosegarten have been considered in this light as well, at least some of them. Already in 1928, Alfred Heuß found compelling similarities between Die Erscheinung, Die Täuschung, and Die Mondnacht and suggested that they be performed together.47 Kramer isolates a “modest Trilogy to the Night” in Die Mondnacht, Das Abendrot, and Abends unter der Linde.48 Walther Dürr refers to a “type of cycle” in the seven Kosegarten settings of October 1815; his arguments in favor of grouping these works are partly based on manuscript evidence, partly poetic mood, partly stylistic likeness.49

Truly narrative collections, with at least one clearly defined protagonist and the unfolding of dramatic content, can also be found in the song literature of other composers of the time. The most famous of these is certainly Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (1816), in which a pensive lover tells the story of his longing for a distant beloved in an uninterrupted sequence of six Lieder. Beethoven makes the unusual decision to tie together the whole by means of musical links between the songs, thereby solidifying the set into a type of through-composed composition. Though this approach is virtually unique, the idea of consecutive songs organized into the telling of a story is not. In 1799 Josef Woelfl published a set titled Die Geister des Sees that relates another tale of longing, this time of a woman who finally encounters her lost mate in the form of a ghost. Friedrich Methfessel’s Des Sängers Liebe, ein kleiner Roman in Liedern (1806?) comes to a similarly tragic end as the blooming of a romance is cut short by the death of the girl. And in Alexis und Ida (ca. 1814) Friedrich Heinrich Himmel assembled forty-six songs “for one, two and several voices” relating the sentiments of a pastoral romance between a shepherd and a maiden.

The twenty Kosegarten settings of 1815 have all the trappings of these types of collections and demonstrate that Schubert was engaged in a similar project of compiling a sequence of songs sung by several characters meant to be performed together—eight years before his radical reconception of song cycle in Die schöne Müllerin. The works are all strophic in construction, short, quite approachable for the amateur singer, and no doubt intended for presentation in a Biedermeier salon. As we have seen, the story of Wilhelm and ill-fated love is a familiar one, echoing those sketched above and countless others from the period. In all, the plot, the musical simplicity, and even the grouping of songs to act out such a story reflect the conceits and cultural practices of its day.

The most common term associated with such groups of songs that collectively told a story and involved multiple characters from this time period was “Liederspiel.” Literally a “song play,” the genre involved the dramatic interaction of several characters, usually spoken dialogue, and Lieder performed at key moments of the story to present the sentiments of the individual figures. The songs demanded little vocal ability, were nearly always strophic, and focused on a single mood or thought. The composer usually credited with inventing the art form is Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814). Writing in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in 1801, Reichardt tells of his abhorrence of vocal exaggeration in the theater, a fashion simply meant to rouse audiences by elevating the aria with effective but empty histrionics: “That inspired in me the thought of trying it with a short, songlike piece whose whole character was set on awakening but a single, pleasant impression and whether the theater public could be made interested in the simple and simply pleasant.”50 Reichardt launched a successful series of theatrical works such as Lieb und Treue that drew their texts largely from well-known poems and highly approachable, sometimes familiar tunes accompanied with a minimum of orchestration. The technique of borrowing implied here drew its inspiration in part from the French tradition of vaudeville, though the dramatic emphasis focused less on raucous parody and more on sentimental, sometimes patriotic topics. Other examples of the form include works by Friedrich Heinrich Himmel (Fanchon oder das Leyermädel, 1804) and Franz Carl Adelbert Eberwein (Lenore, 1829).

Often forgotten in discussions of the Liederspiel are the domestic origins of the genre. In the very next sentence of the passage quoted above, Reichardt continues: “I looked around for something and thought I had found it in a little piece that I had prepared several years previous for a completely different purpose: a domestic party for my own family.”51 The “little piece” that Reichardt transformed into a stage work for the theater reflected a practice of music making in the home that would continue for decades. Although intended for a private audience, such works shared many features with their theatrical namesake: stories told by text and verse involving several characters and the presentation of amateur songs. When produced at home the Liederspiel became something of a parlor game in which the literary sources, song texts, tunes selected, and stories told were chosen and arranged mainly by those attending. This was entirely in keeping with the Biedermeier practice of combining high culture and entertainment: poetry recitations, readings, charades, word games, dramatic sketches, dances, singing, and instrumental performance were all combined, presented, and received for the edification and pleasure of a gathering of friends. This is reflected compellingly in the following contemporaneous review of Hans Georg Nägeli’s Liederkranz auf das Jahr 1816:

The general purpose, which always remains foremost as regards the whole audience, is here, too, to offer these solo songs as a way to promote sociability. The texts are chosen so that they can be sung not by the group but nevertheless in the group by alternating singers. They are especially well suited for small circles where several people capable of singing come together, even though in terms of number and the character of their voices they do not constitute a choir. Such [people] can, in this manner, entertain themselves in a kind of Liederspiel, whose charm will be all the more elevated by the contrast in individuality and voice types, etc.52

This entertainment for friends to be played at home clearly enjoyed a fair share of popularity. The most famous example of this practice is described by Ludwig Rellstab in his biography of the composer Ludwig Berger:

A circle of talented young people had formed in the house of the privy state councilor Stägemann which gave each other poetic assignments …. They posed a type of dramatic puzzle by the name of “Rose, the miller maiden” that one could only solve by linking together Lieder. Rose, the pretty miller-maid is loved by the miller, the garden boy, and the hunter; carefree and a little careless, she gives her heart to the latter, though not without earlier having favored and raised the hopes of the miller. The roles were divided between the members of the circle. The bright daughter of the house [Hedwig Stägemann], endowed with an unusually fine talent for poetry, took the role of the miller maid; Wilhelm Müller became the miller; the painter [Wilhelm] Hensel, later the husband of Fanny Mendelssohn, played the hunter. Each had to express themselves in Lieder in which the relationships to one another were more clearly stated. The game grew to enjoy great popularity.53

As described above, Wilhelm Müller and numerous friends met regularly in the Stägemann home in Berlin and, during the course of their soirees, hit upon the idea of producing a poetic-dramatic rendering of a literary idea that they had borrowed from a popular tale. It was here that Wilhelm Müller found the inspiration for his own cycle of poems, Die schöne Müllerin, written and published years later. Each of the participants was responsible for producing poetry suitable to his or her part at various points in the story. The result was a simply staged play in which the feelings and thoughts of the protagonists and the unfolding of the plot were presented in a sequence of short poetic recitations. When Berger joined their circle some time later, he was employed to set the poems to music so that the roles could be sung. The result was a Liederspiel in which sociability and individual creativity were blended together into a consummate Biedermeier art form. The Berlin friends took their work seriously enough to have it published in 1818 (Figure 8). As Rellstab relates:

There were in all seven suitors around Rose, the pretty miller maiden. Berger initially composed ten purely strophic songs with simple accompaniment titled: “Songs from a Societal Liederspiel: The Pretty Miller Maid” that originally ended with the death of the repentant maiden and the hunter grieving at her grave (as in Goethe).54

Schubert’s Kosegarten settings of 1815 show every indication of having been precisely such a work. The selection of texts to tell a popular story of a fickle heart, infatuation, and tragic despair, the short, strophic songs to be sung by amateurs portraying multiple characters—all point to a Liederspiel. Even the notion of game-playing can be found here, for the song Luisens Antwort reveals Schubert at work in presenting his friends with a type of double parody: Kosegarten’s text constitutes an answer to a very popular poem of the time, “Das Lied der Trennung” by Klamer Eberhard Karl Schmidt. Schmidt’s poem depicts Wilhelm wondering whether his beloved Luisa will remember him now that they are apart; Kosegarten’s Antwort (answer) portrays Luisa confirming how deeply committed she remains to Wilhelm, and even now, “never will Luisa forget you.” Schubert was clearly cognizant of the relationship between these two poems and he chose an ingenious way of acknowledging the connection. Not long after its initial publication, “Das Lied der Trennung” was set to music by Mozart. In turning to Kosegarten’s echo of Schmidt, Schubert likewise invokes Mozart in both the accompaniment pattern and the rhythm of the melody (see Example 9).55 The clever paraphrase was almost certainly not lost on Schubert’s companions.

Figure 8. Title page, Ludwig Berger’s Die schöne Müllerin (1818).

Yet another feature of the Kosegarten songs points to its unusual construction. The thirteenth piece in the set, Das Abendrot, is, properly speaking, not a Lied at all but a vocal trio. Though Schubert set numerous texts in arrangements for two tenors and bass during his life, the voice parts here imply two female singers and one male singer. This interpretation is supported by the texture of the piano accompaniment, but such a constellation is most unusual. In fact, it is the only vocal trio in Schubert’s output that calls for this combination of voices.56 Positioned as it is within the Kosegarten set, however, the part-song makes a great deal of sense. The singing characters of the Liederspiel are joined together in a parenthetic moment of reflection before the last segment of the work turns to its denouement and sorrowful conclusion.

Example 9. Schubert’s parody of Mozart.

Conclusion

Much of Schubert’s life has gone missing in the two hundred years that have transpired since 1815, the year he composed these songs. We have no additional documents that corroborate the existence of this Liederspiel, but we know very little of the details from that year at all. If such material had been preserved, it would no doubt mention the type of music making and socializing that cultivated the domestic Liederspiel in the homes of the culturally inclined of Schubert’s world. Indeed, it would be odd if this highly productive and supremely talented song composer had not attempted to write such a set for his friends given the artistic setting described in what later became known as Schubertiades. Schubert was too aware of the artistic tastes and social practices of his day not to try his hand at this increasingly popular musical innovation. The private nature of such an entertainment combined with its dating to early in Schubert’s career could explain why no effort was made to publish this as a collection.

Eight years would pass before Schubert compiled a cycle he deemed worthy to print. In completing Die schöne Müllerin he unwittingly followed the path of its author Wilhelm Müller, who had taken the Liederspiel that he and his friends had written in 1816 and transformed it into his own poetic project. In so doing, the author radically altered the telling of the story. Rather than having individual figures reflect on their thoughts in a presentational style, Müller interiorized the entire sequence of events into the mind of the miller apprentice. The multi-character play was now an interior monologue, told by a participant in the story whose emotional involvement renders his narrative increasingly unreliable and whose voice is ultimately surrendered to the brook. The cyclical depiction of the sole protagonist caught in a reality that undoes him must have gripped Schubert as it inspired him to set a new a standard for Romantic song. Yet even in reaching for new forms of expression he must have recognized in the plot the outlines of a story or even a “song play” echoing a more innocent perspective from somewhere in his past. By 1823 that time was over, but the Kosegarten settings may well have proved an important early attempt at large-scale organization of songs, an art form that Schubert would come to master as no other. These songs, then, provide us with a previously unobserved perspective on the development of his genius.

NOTES

The initial research for this work was made possible by the Jubiläumsfond of the Austrian National Bank. The author wishes to express his gratitude for this support and to thank especially Otto Brusatti, the project coordinator.

1. This is the first publication that treats the details of this discovery in English; a monograph on the subject is planned. Aspects of this research are discussed in Morten Solvik, “Lieder im geselligen Spiel—Schuberts neu entdeckter Kosegarten-Zyklus von 1815,” Österreichische Musikzeitschrift 53/1 (1997): 31–39; “Finding a Context for Schubert’s Kosegarten Cycle,” in Schubert und seine Freunde, ed. Eva Badura-Skoda, Gerold Gruber, Walburga Litschauer, and Carmen Ottner (Vienna, 1999), 169–82; and “Of Songs and Cycles: A Franz Schubert Bifolio,” in Music History from Primary Sources: A Guide to the Moldenhauer Archives, ed. Jon Newsom and Alfred Mann (Washington, D.C., 2000), 392–99. See also Elizabeth Norman McKay, “Zu Schuberts Vertonungen von Kosegarten-Texten aus dem Jahr 1815,” Schubert durch die Brille 24 (2000): 141–46; Jörg Büchler, “Zur Diskussion über die zyklische Zusammengehörigkeit von Schuberts Kosegarten-Vertonungen aus dem Jahre 1815,” Schubert: Perspektiven 10/2 (2010): 139–55; and Schubert Liedlexikon, ed. Walther Dürr, Michael Kube, Uwe Schweikert, and Stefanie Steiner with Michael Kohlhäufl (Kassel, 2012), 158.

2. Since some songs have survived in more than one type of source, the percentages do not add up to 100 percent. This data is culled from Otto Erich Deutsch, Franz Schubert: Thematisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke in chronologischer Folge, rev. ed. (Kassel, 1978). “Lied” is defined as a song in German for solo voice and piano. These figures include compositionally separate settings of the same text (Bearbeitungen=versions) but not variants (Fassungen) of a single song. For a discussion of this distinction, see Maurice J. E. Brown, Essays on Schubert (London, 1966), 268.

3. For more on the Schubert Liederheft project, see Christopher H. Gibbs, The Life of Schubert (Cambridge, 2000), 79–80. This project was also to include Matthisson and Hölty settings.

4. None of the original fair copies of Die schöne Müllerin have survived, and original manuscripts for only four of the songs are known; see Deutsch, Verzeichnis, 488–89.

5. Two of the manuscripts held in private hands have since been acquired by public collections: A-Wn Mus. Hs. 43.946 and A-Wst 16.400, both fair copies (sigla here and elsewhere stem from RISM, the international index for music sources).

6. See Robert Winter, “Paper Studies and the Future of Schubert Research,” in Schubert Studies: Problems of Style and Chronology, ed. Eva Badura-Skoda and Peter Branscombe (Cambridge, 1982), 209–75.

7. This is confirmed by Walther Dürr in Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke, Series IV, vol. 8: Lieder (Kassel, 2009), xvii, passim.

8. The exception is Hektors Abschied, D312 (text by Schiller), today located in a separate manuscript at the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris.

9. It is thus all the more surprising that until now virtually no serious scholarly effort has sought to make sense of these marginalia. Ernst Hilmar, in “Die Schubert-Autographe der Sammlung Hans P. Wertitsch: Katalog,” Schubert durch die Brille 13 (1994): 3–42, does note inscriptions of this type but provides no explanation for them.

10. Not all marginal markings were added by Johann Wolf. Additional numberings and annotations, especially regarding typesetting, can also be found on many of these pages. Walther Dürr raises this point about sequences of numbers in red crayon (Rötel) frequently situated in the upper-left corner of Schubert manuscripts (Dürr, IV/8, xviii); so far, no comprehensive documented explanation for this different set of numbers has been proposed.

11. On folio 2 recto of A-Wn L14 Münze 2.

12. In Alexander Weinmann, Verlagsverzeichnis Giovanni Cappi bis A. O. Witzendorf: Beiträge zur Geschichte des Alt-Wiener Musikverlages, series 2, no.11 (Vienna, 1967), 207, Johann Wolf is listed as a composer of piano vignettes and paraphrases of Lieder, published mostly from the 1840s through the 1860s.

13. My thanks to Rita Steblin for bringing these to my attention.

14. Handschriftensammlung, Wienbibliothek, I.N.3584.

15. The notice had appeared in the Allgemeine Theaterzeitung 108 (5 May 1848): 436.

16. “Herrn Karl Haslinger zur Erinnerung an den 25-jährigen Bestand seiner musi-kalischen Abende gewidmet 1862,” Handschriftensammlung, Wienbibliothek, I.N.49883. This item is no longer available for study. Haslinger’s father was Tobias Haslinger (1787– 1842).

17. Another work from Wolf’s oeuvre suggests the same conclusion. His “Etüden-Variationen über Franz Schuberts Lied Das Abendroth,” was evidently based on D627 (or possibly the trio D236); D627 was published in 1867, D236 in 1892.

18. See Otto Erich Deutsch, Musikverlags-Nummern, 2nd ed. (Berlin, 1961), 11; and Alexander Weinmann and John Warren, “Diabelli, Anton,” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed. (London, 2001), 7:279–80.

19. That Wolf worked for Spina and not Diabelli can also be seen in other marginal notes. On the verso of A-Wn 43.946 (Geist der Liebe, D233), we find a Wolf reference to a song in the “Verlags Cat. Spina” that is not yet engraved, a sure sign that Wolf had access to an internal listing at C. A. Spina; see Autographen aus verschiedenem Besitz: Auktion am 17 Mai 1960 in Marburg, J. A. Stargardt Catalogue 548 (Marburg, 1960), item 537 after page 126. Walther Dürr, in “Franz Schubert: Das Finden. Von der ersten Niederschrift zur Reinschrift,” in Beiträge zur musikalischen Quellenkunde, 346, also concludes that Johann Wolf worked for Spina, but does not explain the marginalia.

20. The Witteczek-Spaun collection contains two indices of Schubert’s songs titled “Repertorium”; see Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke, Series VIII: Supplement Band 8, Quellen 2: Franz Schuberts Werke in Abschriften: Liederalben und Sammlungen by Walther Dürr (Kassel, 1975), 108.

21. This listing might be the “Aufstellung Schubertscher Lieder von Anton Diabelli” last seen at an auction in Vienna around 1922; see Deutsch, Verzeichnis, 87 (“Anmerkung” to D122).

22. Examples of numberings for each of the categories (except III) can be found in the following manuscripts: I—US-AUS Lake Collection (D228, 229), v; II—A-Wn Mus. Hs. 40.990, r; IV—A-Wn Mus. Hs. 41.628; V—US-Wc Moldenhauer (Das Mädchen aus der Fremde, D117), 1r; VI—US-CA bMS Mus 108(21), r; VII—A-Wn 40.993, r (“von verschiedenen Handschriften”); VIII—US-AUS Lake Collection (D228, 229), v.

23. A look at the songs in these two groups confirms this: the Lieder of Group I and Group II that I have thus far identified are clearly ordered in this fashion. There are only two exceptions among the 41 Lieder that I have been able to assign to these two categories: “I, 57” seems to refer to D645, which we only have in sketch form and might be dated early 1819; it may well have been written before “I, 49” (D923, 1827); “II, 45” seems to refer to D252, written 12 August 1815, long before “II, 43,” D867 (January 1826).

24. It might refer to a generic designation for manuscripts bearing neither signature nor date or signature and no date. Such a determination is at this point not possible.

25. See the discussion of different song versions above.

26. In 1876 Alwin Cranz (1834–1923), proprietor of the music publishing house of August Cranz, bought the firm of C. A. Spina from Friedrich Schreiber. Albert Cranz, a descendant, in the 1950s helped run a part of the firm in Brussels. See Riemann Musik Lexikon (Mainz, 1959), “Personenteil A–K,” 349.

27. Stargardt, September 1957, lot 421.

28. This conclusion may be confirmed by a marginal note in A-Wn Mus. Hs. 41.628, folio 1 verso (early version of Die Mondnacht): in pencil to the right of Wolf’s reference to Group IV is written what appears to be “20 Gesänge.” “Gesänge” is difficult to decipher, but the number is indisputable, which itself seems suggestive.

29. Kosegarten, it seems, used variants of his name throughout his life. The name given here appears on his certificate of baptism; in 1777 he substituted “Theobul” for “Gotthard” and from 1815 went by “Ludwig Gotthard.” See H. Franck, Gotthard Ludwig Kosegarten. Ein Lebensbild (Halle, 1887), 2–3 and 402n1. See also the biography by Kosegarten’s son: Johann Gottfried Ludwig Kosegarten, Kosegartens Leben: Dichtungen von Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten, vol. 12 (5th ed., Greifswald, 1827); and Lewis M. Holmes, Kosegarten: The Turbulent Life and Times of a Northern German Poet (Berne, 2004).

30. For more on Kosegarten’s connection to German Romanticism, see Lewis M. Holmes, Kosegarten’s Cultural Legacy: Aesthetics, Religion, Literature, Art, and Music (Berne, 2005); and Albert Boime, Art in an Age of Bonapartism: 1800–1815, vol. 2 of A Social History of Modern Art (Chicago and London, 1990), 315–635, esp. 377–79, 411–16, and 587–602.

31. For more on this speech, see Kosegarten, Kosegartens Leben, 235–39.

32. Franck, Kosegarten, 240–41 (here and elsewhere all translations mine). The publication announcement to which Schiller refers is probably the same as that which appeared at the back of the Göttingen Musen Almanach of 1798.

33. See the commentary of nineteenth-century literary historians on Kosegarten in Franck, Kosegarten, 161; see also Holmes, Kosegarten and Kosegarten’s Cultural Legacy.

34. Maximilian and Lilly Schochow in their Franz Schubert: Die Texte seiner einstimmig komponierten Lieder und ihre Dichter, 2 vols. (New York, 1974), 1:243–72, propose a volume of Gedichte published in 1788 as well as the complete edition of Kosegarten’s works of 1824 as possible text sources, but admit that neither could have been used by Schubert. Walther Dürr suggests two possibilities in Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke (Kassel), Series IV. In vol. 3b (1982), 265. Dürr identifies Kosegarten’s Poesieen (Leipzig, 1802) as the text source for all but the last of Schubert’s Kosegarten settings but revises his proposal in vol. 5b (1985), 284, to Kosegarten’s Dichtungen. Siebenter Band. Lyrischer Gedichte. Siebentes, achtes, neuntes Buch (Greifswald, 1813) or some related source; in vols. 8 (2009) and 9 (2011) he returns to the 1802 edition as the likely text source. The 1803 source I suggest here, like the 1802 edition, departs very little from Schubert’s text, preserves all titles as they appear in Schubert’s manuscripts, and includes all the Kosegarten settings Schubert ever set (including An die untergehende Sonne, D457). The 1803 edition nevertheless comes closer to the texts in Schubert’s manuscripts; see, for instance, in Abends unter der Linde, (D237), “Mondenblitz” in Schubert’s text underlay and the 1803 edition, not “Morgenblitz” as in the 1802 edition (see vol. 8, 251).

35. The 1815 settings were all taken from vols. 2 and 3. Vol. 1 contains 41 poems, including An die untergehende Sonne, first set by Schubert in 1816, though apparently not completed until 1817 (see Deutsch, Verzeichnis, 271).