The Queen of Golconda, the Ashman, and the Shepherd on a Rock: Schubert and the Vienna Volkstheater

LISA FEURZEIG

Popular theater of Schubert’s time, generally known as the Volkstheater tradition, was a vivid and expressive component of Viennese culture.1 Performed in suburban theaters outside the city walls, Volkstheater plays attracted a broad audience ranging from prostitutes to royalty. The plays held a special position as one of the only outlets, despite censorship, for the social and political concerns of the public. The famous actors and the latest plays and songs—for there was much music in Volkstheater plays—were familiar throughout the city.

In his 1924 introduction to the music for works by playwright Ferdinand Raimund (1790–1836), musicologist Alfred Orel made the claim that the Viennese Classical style was rooted in folk music, observing that “through the deficient knowledge of Viennese folklike music, a great chasm yawns, preventing the rightful understanding of Haydn’s and Beethoven’s works … not to mention Franz Schubert, that most Viennese of all the great masters, who sprang up entirely from the ground of folklike music and raised it to the highest power.”2 Orel does not clearly separate folk and folklike (volkstümliche) music in this comment—which is quite understandable in discussing music of the early nineteenth century, when such concepts were vaguely defined. The important aspect of his observation is that he recognized a pathway leading from the music practiced and enjoyed by ordinary Viennese people to the elevated music of Viennese Classicism—a pathway that even now remains largely unexplored.

“High” and “low” artistic realms in Viennese musical life frequently intersected. As a young man in the early 1750s, Haydn played for the theatrical producer Joseph Kurz and wrote the music for his play Der krumme Teufel (The Crooked Devil); there is a marvelous anecdote of how Kurz histrionically imitated a shipwreck to inspire Haydn’s improvisation at the keyboard.3 Beethoven too was well aware of the Volkstheater, as can be seen in his conversation books: his nephew Karl avidly passed along the theater gossip of the day, and his friend and assistant Anton Schindler was concertmaster of the orchestra in the Josefstadt Theater, founded in 1788—one of three principal venues that presented Volkstheater.

Theatricality was an important part of social life for Schubert and his friends, and their interest in theater took various forms. At the most casual and amateur level were such activities as the game of charades that Schubert, Franz von Schober, and others played at the castle of Atzenbrugg in July 1821.4 At the most ambitious were the plays and operas that Schubert and several librettist friends created in the hopes of having them professionally performed at theaters.

The theatrical activities of the Unsinnsgesellschaft, or Nonsense Society, a group discussed by Rita Steblin in this volume, might be considered as falling somewhere between the improvised and the composed. The handwritten journal Archiv des menschlichen Unsinns (Archive of Human Nonsense) issued by this society in 1817–18 parodied contemporaneous journal publishing by including assorted materials, from reports on politics and science to literary works. Among the latter were several plays that mocked the literary conventions of the time. One example is a play titled Der Feuergeist (The Fire Spirit) that Steblin believes to have been performed in April 1818. Although the journal issues that would have contained the text of the play are lost, a picture representing a scene from it survives, and Steblin argues that this play may have been a source for Schubert’s 1820 melodrama Die Zauberharfe (The Magic Harp), which was performed at the Theater an der Wien, one of the venues presenting a mixed repertoire, including Volkstheater.5

Schubert’s circle of friends both loved and practiced the arts; thus it is only to be expected that they were aware of theatrical news and events throughout Vienna. The writings of Franz von Hartmann, who arrived as a law student from Linz in 1825, suggest the atmosphere. He wrote to his sister Anna von Revertera of the high level of artistic quality in Vienna, “especially galleries and art collections, which all far exceeded my imaginings. As does the theater, the Burg as well as the Leopoldstadt, totally opposed as they are to each other.”6 It is significant that Hartmann mentions both these theaters. The first functioned as the center for classical drama, whereas the Leopoldstadt, founded in 1781 just across the Danube Canal from the inner city, was the central venue for Volkstheater. Hartmann’s comment shows that a sophisticated member of the upper middle class was drawn to both repertoires.

Given this cultural context, it is reasonable to assume that the two documented occasions when Schubert attended specific Volkstheater plays represent just the tip of the iceberg—he and his friends were no doubt immersed in this theatrical tradition.7 Furthermore, they were linked to the most important Volkstheater playwright of the 1820s, Ferdinand Raimund, who began his career as a comic actor and was well known to Schubert’s good friend Eduard von Bauernfeld, who may have introduced the composer and the dramatist.8 Both Raimund and Schubert were torchbearers at Beethoven’s funeral in March 1827. As it happens, Schubert also knew Johann Nestroy (1801–1862), whose more cynical plays would take over the Viennese stage in the 1830s. Nestroy had been a fellow student at the Stadtkonvikt (City Seminary). Schubert attended some of Nestroy’s performances as an opera singer, and Nestroy, who was a fine bass, participated in public performances of some of Schubert’s vocal quartets both in Vienna and in Amsterdam.9

The purpose of this essay is to explore several instances in which Schubert’s music is notably similar to that of extremely well-known Volkstheater songs—similar enough to suggest that Schubert may have intended deliberate references to Volkstheater music.10 In one such example the play involved was a classic of the genre, dating from the 1790s, and in the other three cases Schubert composed his work soon after the premiere of the relevant play. Taken together, these situations suggest that he was familiar with both the enduring Volkstheater tradition and the latest important works. The first two cases are based on observations already made by others; the second pair is presented here for the first time. In all instances the examples depend on a combination of musical and textual resemblances between the works compared. The musical similarities are not conclusive on their own, but when combined with shared textual elements—ranging from a single syllable to plot similarities to an overarching idea—they carry much more weight.

Such complex forms of reference offer a remarkable window into Schubert’s creative mind. It is widely recognized that as a song composer he unified music and text in extraordinary ways. The theatrical situations—in which textual relationships and musical connections to an outside source go hand in hand—provide further examples of how his mind operated. They may suggest models for similar readings of other works, helping us to identify larger meanings for Schubert’s music.

Schubert does not directly quote his musical sources from the Volkstheater; rather he reshapes certain elements in ways that suggest another piece of music was a partial source for his own. This was a shrewd strategy given the Austrian political situation in Clemens von Metternich’s Vienna. Censorship and police surveillance were the norm—but within that context Volkstheater plays took some liberties, criticizing government and society in ways that were impossible elsewhere—and deniability was advantageous.11

Ich hört’ ein Bächlein rauschen and Wer niemals einen Rausch hat g’habt

In an article about Schubert written some forty years after his death, Eduard von Bauernfeld recalled some discussions with the composer in which he criticized various aspects of his friend’s compositional style:

With Schubert, so much about form, musical declamation, and the fresh melodies can be reproached. [The melodies] sometimes sound too national [vaterländisch], too Austrian; they recall folk tunes whose rather low tones and unbeautiful rhythms do not have full rights to push their way into the poetic art song. On this topic, it sometimes came to little discussions with Master Franz. Thus when we tried to prove to him that certain passages in Die schöne Müllerin recalled an old Austrian grenadiers’ march or Wenzel Müller’s Wer niemals einen Rausch hat g’habt. — He grew seriously angry about such petty, carping criticism, or else he laughed at us and said, “What do you understand? That’s the way it is, and it has to be that way!”12

Evidently, the link between Classical and folk traditions that Orel posited in 1924 would have troubled some young intellectuals a century earlier. Bauernfeld’s account makes it clear that Schubert did not share that perspective. When his friends made class distinctions between folk music and art song, he either grew angry or simply laughed at the notion that to mix these genres was inappropriate.

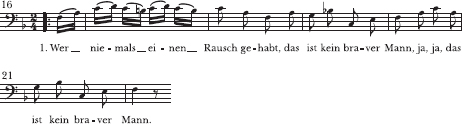

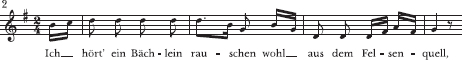

The song in which Schubert’s friends heard a link to Wenzel Müller’s Wer niemals einen Rausch hat g’habt must be the second song of Die schöne Müllerin, namely Ich hört’ ein Bächlein rauschen. The passages quoted in Examples 1 and 2 show the openings of both.

Example 1.Wenzel Müller, Wer niemals einen Rausch g’habt, vocal line, mm. 16–22.

Example 2. Franz Schubert, Ich hört’ ein Bächlein rauschen, vocal line, mm. 2–6.

Each melody moves up to the fifth scale degree, hovers on or around it, and then moves downward a full octave before coming to rest on the tonic note. In the process of descent, both melodies use the figure ˆ5–ˆ3–ˆ1 followed by other arpeggiations. These musical relationships are quite noticeable on their own, and they are strengthened by the texts, because the syllable rausch appears at the same moment in each phrase.

This textual parallelism creates a kind of pun, because the words rauschen and Rausch have entirely different meanings. The verb rauschen means to rustle or murmur and describes the sound that the miller hears as he approaches the brook. The noun Rausch means the state of being intoxicated. The character who sings Wer niemals in the play Das Neusonntagskind (Fifth Sunday’s Child) is quite the opposite of the protagonist in Die schöne Müllerin. While the miller is young, innocent, and hopeful as he sets out to seek his fortune, the play’s Hausmeister (Caretaker) is jaded and grumpy (though basically goodhearted), fond of the pleasures of alcohol, and prone to become deaf whenever someone needs him to open the door—unless the jingle of coins is added to the soundscape. The play by Joachim Perinet premiered in 1793, and the character of the Hausmeister became a Viennese classic.13 Indeed, the Hausmeister’s song praising drunkenness soon moved into the category of a folksong.14 There is specific evidence that friends of Schubert were familiar with the song, as it is mentioned in an 1817 document of the Nonsense Society. The motto at the top of the society’s newsletter of 4 December is the opening of the Hausmeister’s song, “Wer niemals einen Rausch hat g’habt der ist kein braver Mann!” (Anyone who has never been drunk is not a good man!)—which is then labeled as being from Act 7, scene 36 of Don Carlos.15 Thus Perinet is implicitly and satirically equated with Friedrich Schiller. Both the implication that Schiller is long-winded and the idea of linking such a revered writer of Weimar classicism with an icon of the popular theater are very much in the spirit of Viennese comedy of this period. One common literary practice in the Volkstheater tradition was the Verwienerung (or “Viennacization”) of well-known stories including Bluebeard, Othello, and various Greek myths. In musical quodlibets within their Volkstheater plays, composers delighted in mixing operatic and symphonic selections from composers such as Haydn, Mozart, Rossini, and Spontini with folksongs and songs from other popular plays.16 By allowing a folklike tune into his elevated song cycle, Schubert showed more affinity with these musical practices of the Volkstheater than with the taste of his friends.

The connection between the two songs goes beyond the play on the words Rausch and rauschen. It also suggests a deeper foreshadowing: the miller’s encounter with the brook will lead to intoxication, and the apparently innocent rauschen will culminate in a deadly Rausch.

Aline and the “Wanderer” Fantasy

We move next to a more elaborate connection, this one between a theater song and an instrumental work based on one of Schubert’s Lieder. On 19 October 1822, Schubert went to the Leopoldstadt Theater and saw Aline, oder Wien in einem andern Welttheile (Aline, or Vienna on Another Continent), a play by Adolf Bäuerle with music by Wenzel Müller. The author of the play was important not only because he was one of the three central playwrights of his day, but because as editor of the Theaterzeitung he had a huge influence on theatrical matters in Vienna.17 A month after attending this performance, Schubert composed his Fantasy in C Major (D760), generally known as the “Wanderer” Fantasy because of its quotation from Schubert’s song Der Wanderer (D489) on a text by Schmidt von Lübeck. Hans Költzsch, in his seminal study of Schubert’s piano music, pointed out similarities between the waltz theme in the scherzo section of that piece and a duet from Aline that begins “Was macht denn der Prater, sag blüht er recht schön?”18 See Examples 3 and 4.

As in the previous case discussed, we find definite similarity without direct quotation. The dotted rhythms are a strong link, and the melodies are quite similar. At the end of the fourth bar of each passage, the melodies diverge, with Müller’s ending on the third scale degree, while Schubert’s ends on the fourth. At the openings of their second phrases, however, each tune immediately moves to the scale degree that was emphasized by the other one, creating a kind of virtual cross-relation.

Example 3. Wenzel Müller, duet from Aline, vocal lines, mm. 32–40.

Example 4. Franz Schubert, “Wanderer” Fantasy, right hand, waltz theme, mm. 405–20.

Költzsch pointed out the relationship between these two passages, but provided no interpretation, leaving it an open question why Schubert might have linked his piano fantasy with a recent Volkstheater song. To suggest an answer, it is once again important to know some particulars about the play and the song. The “Wanderer” Fantasy has no sung text that we can turn to for answers, but its association with Schubert’s earlier song links it to the Romantic archetype of the wanderer.19 How might this be related to Bäuerle’s play and the duet?

The play’s ancestry goes back to the French novella Aline, reine de Golconde (1761), written by the Chevalier Stanislas de Boufflers (1738– 1815). The heroine is a milkmaid who is seduced by a fashionably decadent young nobleman, as in many eighteenth-century French “philosophical” novels.20 Instead of falling into ruin, she rises through the demimonde until she becomes the enlightened monarch of Golconda, a prosperous state in India. Many years later, when her former lover shows up there, she wins him back by using the resources at her command to stage a recreation of the scene of her initial seduction, with herself costumed as the milkmaid she once was, convincing him of the value of what he had thrown away when he was too young to appreciate it.

This story captured the European theatrical imagination, inspiring numerous ballets and operas across Europe from the 1760s until well into the nineteenth century.21 The most widely known version was a French opera composed in 1803 by Henri Berton (text by J. B. C. Vial and E. G. F. de Favières) that in 1804 reached Vienna, where it was performed twenty times in the court theaters in German translation. Johann Michael Vogl, later the preeminent champion of Schubert’s songs, performed the important role of Osmin, and he also composed the duet Ich widme dir mein ganzes Leben to be substituted in the Vienna version for a duet by Berton. Vogl’s duet was sufficiently familiar to Viennese audiences to be included together with many well-established favorites from both Volkstheater and opera sources in the smash hit quodlibet play performed at the Theater an der Wien for the 1809 carnival season: Rochus Pumpernickel.22 Schubert himself had encountered the Aline story before the performance of Bäuerle’s play at the Leopoldstadt. The first play with music by Schubert to be performed in a major theater, Die Zwillingsbrüder, had six performances at the Kärntnertor Theater, each time as the first half of a double bill, and on 21 July 1820 it was paired with a ballet version of Aline.23

The story of Aline evokes the conflicting emotions of Romantic wanderers, who typically feel the urge to leave their homes but are then tormented by longing (Sehnsucht) for what they have lost. Aline—an example of the rare female wanderer in this period—travels a great distance to another continent, but then paradoxically wins her former lover back through nostalgic memories of her humble childhood home. (In Bäuerle’s Vienna-centered version, the specific location she conjures up is the Brühl, a forest area outside the Vienna suburb of Mödling.)

Schubert’s waltz theme echoes the Bäuerle-Müller duet mentioned earlier, which is sung by the play’s secondary couple of Zilly—Aline’s confidante, also from Austria—and Bims, the ship’s barber. Zilly, posing as the queen and pretending to know nothing about Vienna, nevertheless asks very pointed questions that show her specific knowledge of the city, and Bims fills her in on the latest developments in the Imperial capital. (This duet provides clear evidence of the improvisatory element in the Volkstheater, as variants are seen in several sources. Rommel’s reprint of the play and two piano-vocal scores all differ in textual details.)24

The duet text alternates between praise and satire. An example of praise:

Nur noch ein Wört’l, was g’fällt denn in Wien? |

One more word: What do people like in Vienna? |

Ehrliche Leut’ und ein fröhlicher Sinn. |

Honest people and a merry spirit. |

On the ironic side, the disastrous finances of the empire are skewered in other passages:

Nun, und der Kalteberg25 [sic] ist noch in Wien? |

So, is the Kahlenberg still in Vienna? |

Den habn’s jetzt verschrieben, er geht nach Berlin. |

They’ve signed it over, it’s going to Berlin. |

Ist noch die Schwimmanstalt, schwimmt man noch dort? |

Is there still a public pool, do people still swim there? |

Mit Schulden da schwimmen s’ ohne Wasser oft fort. |

They’re swimming away in debt, even without water. |

In most versions, the duet ends with a lovely self-referential twist:

Was jetzt im Leopoldstädter Theater vorgeht? |

And what’s happening now in the Leopoldstadt Theater? |

Da singt just die Zilly mit dem Bims ein Duett. |

Zilly is singing a duet with Bims.26 |

This multivalent message leaves the question open of just how the refrain is intended. “Ja nur ein Kaiserstadt, ja nur ein Wien” (Yes, only one Imperial city, yes, only one Vienna) seems to express praise, but if said in the proper ironic tone, it could be meant cynically instead, as in “Yeah, it’s only Vienna.” The cynical reading is supported by Bäuerle’s next play, Wien, Paris, London, Constantinopel, which premiered five months after Aline in March 1823: the main characters receive a set of magical objects as they set out on their journeys, one of which is a purse that fills up with money whenever they think nice thoughts about Vienna.

By obliquely referencing the Aline duet, Schubert may have meant to evoke in his audience a sophisticated mixture of emotions: the tragic Romantic yearning of the poem “Der Wanderer” and of Schubert’s setting is intermingled with Bäuerle’s down-to-earth language and ironic rhetorical strategy that critiques Vienna in the very process of praising it. Perhaps this emotional mix reflects the ambivalence of the intelligent artist who in 1822 might both want to leave home and at the same time feel the need to stay.27

Winterreise and Der Bauer als Millionär

On 10 November 1826, a new play, Raimund’s Das Mädchen aus der Feenwelt, oder der Bauer als Millionär (The Maiden from the Fairy World, or The Peasant as Millionaire) had its premiere at the Leopoldstadt Theater. It was an enormous success, first in Vienna and then in several German cities. Raimund played the title role of Fortunatus Wurzel, a simple peasant who is used as a pawn by magical forces so that he becomes fabulously rich and then loses his money and his youth overnight. The music was composed by Joseph Drechsler (1782–1852), and two songs instantly became favorites, probably because they went beyond the particulars of the plot to become emblems of a widespread and general state of mind. There is significant evidence to support the belief that Raimund himself wrote the melodies of these songs; Orel includes facsimiles of both, written in music notation in Raimund’s handwriting, along with quotations from Raimund documents commenting on his compositional work.28

No documentation exists to prove that Schubert attended this play, but we know that his friends the Spauns did, on 21 December 1826, and that Schubert was with them later that evening, so it is likely that the play was discussed.29 I argue that both of these songs have parallels in Schubert’s Winterreise that are identifiable through musical and textual relationships.

Commentary from the time reveals how deeply the play—and in particular Fortunatus Wurzel, the central figure played by Raimund himself—moved the audience. For example, renowned German actor Ludwig Devrient “under [Raimund’s] spell, exclaimed, ‘The man is so true that a miserable person like myself freezes and suffers along with him.’ … ‘The whole house rejoiced, laughed, and cried, and I rejoiced and laughed and cried with them,’ reported an eyewitness.’”30

In order to grasp the play’s connection with Schubert’s music, we must examine Wurzel’s key scenes. Before the play begins, he is a simple peasant who is raising a foster daughter, little realizing that her mother, Lakrimosa, is a once-powerful fairy undergoing a punishment for her vainglory. For Lakrimosa to be redeemed, her daughter must grow up simply and marry an ordinary person by her eighteenth birthday—but two years before the play begins, the allegorical Envy, enraged after being rejected by Lakrimosa, has taken revenge on her by making Wurzel a wealthy man. He now lives in a great city, surrounded by flattering admirers; he indulges his appetites to excess; and he insists that his daughter must marry a rich man rather than the fisherman she loves. As Lottchen’s eighteenth birthday approaches, a grand battle of supernatural beings rages around the unknowing Wurzel. Angry at Lottchen for defying his wishes, he throws her out of the house, and he then receives a visit from an unknown person who claims to be an old friend: Jugend, or Youth. This role was played by Therese Krones, a beloved actress of the time, and Zentner observes that she “fascinated all Vienna. She too had found a task perfectly suited to her nature, and her legacy in theater history lives mostly through this role.”31

Jugend has come to say good-bye to Wurzel, who does not recognize this “old friend” or understand what is happening. In the first famous song, Brüderlein fein, Jugend begs Wurzel to forgive him and not hold a grudge when he departs. Wurzel first tries to bribe Jugend to stay, then grows angry—but finally the two sing an affectionate farewell. This song reached folksong status in Vienna, apparently because it captured a sorrowful, nostalgic mood that suited the 1820s, when the exciting years of the Congress of Vienna and the defeat of Napoleon were giving way to the frustrations of Metternich’s Restoration.

After Jugend goes offstage, Wurzel receives another visit, this time from Old Age (das hohe Alter). He is instantly transformed into an old man, his mansion disappears, and he finds himself back in the countryside. When he next appears in the play, he has just begun his new job as an Aschenmann, a collector of ashes. He expresses his newfound humility in the Aschenlied, whose text contrasts the vanity of wealth and ambition with the true values of love and faithfulness. In its original form, the song had three stanzas; here, to give a sense of its style and meaning, are the first and third:

So mancher steigt herum, |

Many a man rises up, |

Der Hochmut bringt ihn um, |

Arrogance brings him down, |

Trägt einen schönen Rock, |

Wears a nice coat, |

Ist dumm als wie ein Stock. |

Is dumb as a stick. |

Von Stolz ganz aufgebläht, |

All swollen with pride, |

O Freundchen, das ist öd, |

O my friend, that is empty, |

Wie lang stehts denn noch an, |

However long you put it off, |

Bist auch ein Aschenmann! |

You’re also an ashman! |

Ein Aschen, ein Aschen! |

Ashes! Ashes! |

Figure 1. Therese Krones as Jugend.

Yet much in the world, |

|

Ich mein nicht etwa’s Geld, |

And I don’t mean money, |

Ist doch der Mühe wert, |

Is really worth the trouble |

Daß man es hoch verehrt. |

That we should honor it highly. |

Vor alle braven Leut, |

To all good people, |

Vor Lieb und Dankbarkeit |

To love and gratitude, |

Vor treuer Mädchen Glut, |

To the ardor of faithful maidens, |

Da zieh ich meinen Hut. |

I take off my hat. |

Kein Aschen! Kein Aschen!32 |

Not ashes! Not ashes! |

Like the Aline duet, this song was a perfect candidate for added stanzas caricaturing various types of people, and recent performances continue to feature such additions, frequently commenting on current events or scandals.33 Just a month after Raimund’s death in 1836, two newly written stanzas in tribute to him were sung on the stage of the Leopoldstadt. The use of this song as a vehicle for such homage reflects how closely the Viennese public identified Raimund with the poignant figure of the Aschenmann.34

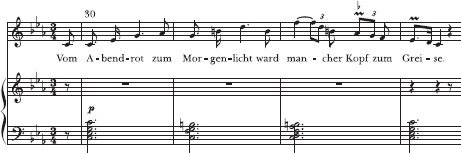

Two songs from the second half of Schubert’s Winterreise can be linked to Der Bauer als Millionär: Der greise Kopf and Die Krähe. In Der greise Kopf, the winter wanderer notices that his head has been sprinkled with snow, giving him the appearance of an old man—but alas, this is only an illusion. The lines were probably intended metaphorically by Wilhelm Müller—but in Der Bauer als Millionär this literally happens to Wurzel. The link to the song cycle is strengthened by the circumstance that Wurzel’s transformation is accompanied by the sudden magical onset of winter.

Vom Abendrot zum Morgenlicht |

From sunset to morning light |

Ward mancher Kopf zum Greise |

Many a head has turned gray |

The song Brüderlein fein is a reflection on friendship at the moment that the allegorical friendship between Wurzel and Jugend is ending, in the sense that his youth is saying farewell to him. In Die Krähe, the wanderer questions the faithfulness of a crow who is following him:

Krähe, wunderliches Tier, |

Crow, marvelous animal, |

Willst mich nicht verlassen? |

Wilt thou not abandon me? |

The crow, he realizes, is expecting his death and hopes to eat his corpse, but he ironically compares its steadfastness with the fickleness of his beloved:

Krähe, laß mich endlich sehen |

Crow, let me finally see |

Treue bis zum Grabe. |

Faithfulness unto the grave. |

What is noteworthy here is that the situations are inverted. Jugend is leaving Wurzel, but still wishes him well and begs for forgiveness. The crow stays beside the wanderer like a faithful lover or friend, but its behavior results from its selfish needs rather than true concern for another. This inversion makes the comparison between the two situations all the more interesting.

Let us presume that Schubert deliberately incorporated references to the two famous songs from Der Bauer als Millionär into Winterreise. To do so while still preserving the musical style and expressive goals of his song cycle must have been a challenge. As a result, the resemblances between the two pairs of songs are fleeting and subtle, particularly in Die Krähe.

Example 5 shows the first half of the Aschenlied, omitting the introduction. Example 6 shows the key phrase of Der greise Kopf, which is heard three times in the song: as the piano introduction, the first vocal phrase, and then again near the end of the song; the final occurrence is shown here. The Schubert phrase first ascends, in a slightly winding arpeggiated melody, then arrives at an accented tritone (B–F) before descending in a more direct manner. Susan Youens interprets this phrase as a summary of the emotional trajectory of the song, with the ascent representing the wanderer’s joy when he believes himself to be old and the descent representing his disillusionment that this is not the case.35 The two-bar phrase at the end of the Aschenlied example shares the ascent-descent contour and also features a central accented tritone (C–F♯). Youens points out that the prosody of the Schubert phrase is very unnatural the first time it is sung, on the words “Der Reif hatt’ einen weißen Schein mir übers Haar gestreuet” (The frost had sprinkled white over my hair), with strong beats falling on the unaccented syllables “ei(nen)” and “ü(bers)”—yet when the phrase is heard later, “the prosodic accents more accurately and expressively emphasize the last light of dusk and the first light of morning, the nocturnal span in which others grow old but not the unfortunate wanderer.”36 This shift from awkward to appropriate prosody suggests that Schubert was thinking of the later phrase—the one that matches Wurzel’s story—when he first composed the melody.37

Example 5. Joseph Drechsler, Aschenlied, mm. 1–8.

Example 6. Franz Schubert, Der greise Kopf, mm. 30–33.

Example 7. Joseph Drechsler, Brüderlein fein, mm. 1–5.

The musical connection between the other two songs is principally in their opening motives. The plaintive melody that opens Brüderlein fein—which occurs twice in a row and is sung repeatedly by both Jugend and Wurzel—served as a symbol for the whole song and its significance (Example 7). Die Krähe opens with the same three-note neighbor motive, but then drops a fourth instead of a third (Example 8). This could be a chance similarity—but the prominence of Raimund’s play and its particularly famous songs at the precise time when Schubert was composing Winterreise, along with the other connection to Der greise Kopf, bolster the argument for seeing it as more than that.

Another network of connections between Winterreise and the songs of Der Bauer als Millionär deserves brief mention. Just as the first four notes of Brüderlein fein became that song’s signature, so the last notes of the Aschenlied came to represent that song as well. On the words “Ein Aschen” or “Kein Aschen,” the singer first drops a sixth, then moves up a half step: C–E–F. Though this musical gesture is not uncommon, its recognizability as the melody for the Aschenlied’s refrain marked it as significant. Schubert uses this same set of intervals, on the same exact pitches, at the ends of several phrases in Das Wirtshaus, the twenty-first song of the cycle. And this recalls yet another song in Der Bauer als Millionär, Die Menschheit sitzt um bill’gen Preis (Mankind Sits for a Low Price), in which Wurzel compares the stages of a human life to a meal at a Wirtshaus—and the phrase “so endigt sich der Lebensschmaus” (so ends the feast of life) ends with this same motive of a falling sixth followed by a half step.

Example 8. Franz Schubert, Die Krähe, mm. 6–9.

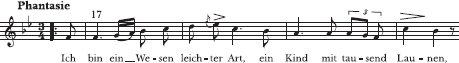

Der Hirt auf dem Felsen and Fantasy’s Aria

The final case to be presented concerns another Raimund play, Die gefesselte Phantasie (Fantasy Bound), whose premiere took place at the Leopoldstadt Theater on 8 January 1828.38 In this play, Raimund—who, according to Bauernfeld, was always convinced that he was meant to be a tragedian—reflects somewhat satirically on the relation between high and low art. Queen Hermione is in love with Amphio, a shepherd who is also a good poet, so she proposes to marry whoever wins a poetry contest. Some evil spirits, determined to thwart the queen’s desires, tie up Fantasy, the muse, so that none of the poets are able to create anything at all. She is finally released only when she desperately begins to sing a quodlibet, which persuades Jupiter to smash her chains with a thunderbolt. Reunited with Fantasy, Amphio is able to write a winning poem and all ends happily. Ironically, it turns out he is actually a prince in disguise, but in the meantime Raimund has made various points about the relative merits of high and low art.

Act 1, scene 12 of Die gefesselte Phantasie features Amphio alone. The opening stage direction reads “Amphio sits on a stone and plays a soft song on his flute.” This scenario recalls Schubert’s scena or extended song, Der Hirt auf dem Felsen (The Shepherd on the Rock, D965), which was composed in October of that same year. The shepherd in that work, also sitting on a rock, thinks longingly of his beloved while looking into the valley below, and he too is accompanied by a woodwind instrument (though it is a clarinet rather than a flute). These connections suggest the possibility that music from Die gefesselte Phantasie may be associated with Schubert’s piece.39 Another, more subtle relationship arises when we realize that although the shepherd in Der Hirt auf dem Felsen is a male character, the work was composed for soprano Anna Milder-Hauptmann. Similarly, Therese Krones, who sang the soprano role of Fantasy, was best known for playing the male character Jugend in Der Bauer als Millionär.

As with two of the Volkstheater works discussed earlier, the music for this play was written by Wenzel Müller, close to the end of his long career. When Fantasy first appears she introduces herself with a delicate song, suitable to the words that describe Fantasy’s whimsicality and her many guises. The opening stanza begins as follows:

Ich bin ein Wesen leichter Art, |

I am a being of a light kind, |

Ein Kind mit tausend Launen, |

A child with a thousand whims, |

Das Nied’res mit dem Höchsten paart, |

Who pairs the low with the highest, |

‘S ist wirklich zum Erstaunen. |

‘Tis truly astonishing. |

Müller writes a substantial introduction before Fantasy begins to sing (the beginning is shown in Example 9). The opening motive tellingly pairs low and high, beginning with an elaboration of the note F in bass clef and ending much higher, with parallel sixths descending a third in the soprano range. The first mini-phrase (mm. 1–2) outlines an interval of a sixth (F–D), and its altered repetition in mm. 5–6 extends the span to a seventh (F–E♭ The opening vocal melody (Example 10) composes out the two versions of the introductory motive by filling in that seventh.

Like this piece, Der Hirt auf dem Felsen opens in ¾ time and in the key of B-flat major. The opening gesture, though, seems to hover on D minor, hinting at a G minor that does not arrive here but will later be heard as the key of the middle section. Where Müller’s opening elaborates on the pitch F and leaps up a sixth to D before dropping a third, Schubert begins on D, elaborates on this pitch, and then drops a fourth (see Example 11). The third and fourth bars of Schubert’s version are reminiscent, in an indirect way, of Müller’s first two bars. At the same time, this melancholy, yearning opening meets Schubert’s own expressive needs.

Example 9. Wenzel Müller, Fantasy’s aria, mm. 1–8.

Example 10. Wenzel Müller, Fantasy’s aria, vocal line, mm. 17–20.

Müller’s opening gesture finds another echo much later in the Schubert piece, at the start of the final section. As noted above, Fantasy’s aria expands from a leap of a sixth to that of a seventh, and the seventh is then filled in as a scale in the vocal melody. (The presence of a grace-note F in the vocal line does two things. On the one hand, it fills out the whole octave; on the other, by putting a little interruption between scale degrees 6 and 7, it reinforces both the sixth and the seventh that existed as leaps in the introduction.)

Schubert completes the process in his final section, in which the melody ascends a sixth, leaps back down, and then ascends a seventh—thus far imitating Müller’s opening. Schubert’s vocal line then rises through the full octave, taking a different path from that point on.

Example 11. Franz Schubert, Der Hirt auf dem Felsen, mm. 1–4.

Example 12. Franz Schubert, Der Hirt auf dem Felsen, clarinet part, mm. 1–3 of Allegretto.

Final Reflections

Taken together, these four case studies link pieces by Schubert to famous Volkstheater works of his day—or, in the first example, to a piece from an earlier generation that had endured in the collective Viennese memory. They vary in the degree of musical and textual similarity, and perhaps also in the purpose and meaning of any intended correspondence. The first two cases present stronger musical resemblances than the later pair. Yet the striking plot relationships between the Schubert works and the two Raimund plays—in which we encounter a person whose hair turns white overnight, and there really is a shepherd on a rock thinking of his beloved—give meaning to the musical ties, though they are fleeting and subtle.

There is no way to prove that these references are deliberate. If Schubert was aware of what he was doing, he was not trying to draw attention to the connections, for had he wanted to, he could have quoted much more directly. If these were conscious references, I believe they were intended for his own understanding and that of anyone else who would both recognize the links and take them in the proper spirit. As Bauernfeld remembered, Schubert responded angrily when his friends appeared to criticize connections of this kind.

While some composers, such as Alban Berg, devised hidden musical references that concealed information about their personal lives,40 Schubert’s associations of his music with Volkstheater works do not veil secrets of that kind. Rather, they first signal his interest in those works and then draw connections between them and his own music. By associating his music with the popular tradition, Schubert was allying himself with the comprehensive Viennese approach to the arts that Alfred Orel acknowledges when he attributes the strengths of the Viennese Classical tradition in part to its roots in folk music. Schubert was repudiating the purist approach exemplified by some of his friends when they argued that he should not use such common sources as folk tunes and marches in elevated genres such as the Lied. He was accepting the exuberant, irreverent side of Viennese culture that delighted in quodlibets, juxtapositions of “high” and “low” art, clever intertextual references, and surreptitious critiques of the authoritarian government. He was absorbing, developing, and commenting on the thoughts and perspectives of Volkstheater writers—Bäuerle’s satiric praise of the Imperial capital, Raimund’s poignant tribute to honesty and goodness in a world of corruption and deception—while also paying tribute to the music of his Viennese theatrical colleagues, Wenzel Müller and Joseph Drechsler. He was avoiding the simple categories that divided music in his time (as in our own), and embracing the full complexity and diversity of his native city.

Recent writing on Schubert has revealed many aspects of his music that were unrecognized or unformulated in the past, broadening our understanding of his numerous complicated strategies as a composer. Some scholars have focused on musical elements, discovering new and elaborate musical structures and approaches to harmony.41 Others have emphasized his approaches to poetry that include dramatic, psychological, and intellectual elements in various cases, depending on the text.42 These connections between Volkstheater works and Schubert’s compositions reveal another aspect of Schubert the interpreter: one who drew upon the vibrant popular tradition of his home city for his own expressive purposes.

Although I am the author of this essay, all the work described here was done jointly with John Sienicki, who has explored the Volkstheater repertoire in depth. He was the first to notice and investigate some of the musical relationships discussed. I am grateful to Raymond Erickson and Walter Frisch, who offered very helpful feedback on an earlier version of this essay.

1. The Volkstheater tradition has not received much scholarly attention. The essential and magisterial history of the subject is Otto Rommel, Die Alt-Wiener Volkskomödie: Ihre Geschichte vom barocken Welt-Theater bis zum Tode Nestroys (Vienna, 1952). Rommel also published several important plays in reprint editions. More recent works include Jürgen Hein, Das Wiener Volkstheater (Darmstadt, 1997); and Beatrix Müller-Kampel, Hanswurst, Bernardon, Kasperl: Spaßtheater im 18. Jahrhundert (Paderborn, 2003). Hein has also published a set of reprints, Parodien des Wiener Volkstheaters (Stuttgart, 1986). All these writers are literary scholars, and they do not discuss the music beyond acknowledging that it was usually present. For an overview in English of the Vienna theaters during Schubert’s lifetime, see Simon Williams, “The Viennese Theater” in Schubert’s Vienna, ed. Raymond Erickson (New Haven, 1997), 214–45. Alfred Orel’s introduction to the music volume of Raimund’s complete works includes a brief but impressive discussion of Volkstheater music, with attention to general characteristics, various genres, and differences between composers. Peter Branscombe also wrote about Volkstheater music; see “Music in the Viennese Popular Theater of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 98 (1971–72): 101–12.

2. Alfred Orel, Ferdinand Raimund: Die Gesänge der Märchendramen in den ursprünglichen Vertonungen, in Sämtliche Werke, vol. 6 (Vienna: Schroll, 1924), ix.

3. See Rommel, Alt-Wiener Volkskomödie, 364.

4. See Otto Erich Deutsch, The Schubert Reader (New York, 1947), 184–85.

5. See Rita Steblin, Die Unsinnsgesellschaft: Franz Schubert, Leopold Kupelwieser und ihr Freundeskreis (Vienna, 1998), 26–31, 196. The Theater an der Wien (1801) was first established as the Freihaus Theater in 1787.

6. See Neue Dokumente zum Schubert-Kreis, vol. 2: Dokumente zum Leben der Anna von Revertera, ed. Walburga Litschauer (Vienna, 1993), 34 and 56. The “Burg” or Burgtheater was another designation for the Kärntnerthor, or the court theater. Two years earlier, in October 1823, Anna’s future husband had also visited Vienna, and he wrote to his fiancée about his visits to three theaters: the Josefstadt, Kärntnerthor, and Leopoldstadt. In 1826, Franz von Hartmann’s diary refers to Schwind and Schober’s attending Karl Meisl’s play Die beiden Spadifankerl and the Spauns attending Ferdinand Raimund’s play Der Bauer als Millionär. See Deutsch, Schubert Reader, 578, 580.

7. Peter Branscombe assembled a list of the twenty-two occasions when Schubert is reported to have attended various theatrical performances; see “Schubert and the Melodrama,” in Schubert Studies: Problems of Style and Chronology, ed. Eva Badura-Skoda and Peter Branscombe (Cambridge, 1982), 110–11. The two Volkstheater plays on that list are Adolf Bäuerle’s Aline, on 19 October 1822, and J. A. Gleich’s Herr Josef und Frau Baberl—mentioned by Schubert, but with “Josef” misnamed as “Jacob” in a letter to Eduard von Bauernfeld—in May 1826. For both plays, the music was by Wenzel Müller. See also Deutsch, Schubert Reader, 236 and 528.

8. See Bauernfeld, Bilder und Persönlichkeiten aus Alt-Wien: Erinnerungen an Moritz von Schwind, Franz Schubert, Franz Grillparzer, Ferdinand Raimund, Johann Nestroy, Anastasius Grün und Nikolaus Lenau, ed. Wilhelm Zentner (Altötting, 1948), 50–55.

9. For details on Schubert’s links to Nestroy and Raimund, see Schubert-Enzyklopädie, ed. Ernst Hilmar and Margret Jestremski (Tutzing, 2004), 2:513–14 and 581–82.

10. Schubert’s own theatrical works do not seem to refer to the Volkstheater in similarly specific ways, though of course it is possible that connections will be identified in the future. My best guess as to why we do not find Volkstheater references in Schubert’s operas is that he was less practiced in that genre and perhaps always anxious to follow stylistic models in order to achieve success.

11. Kristina Muxfeldt discusses Viennese censorship and hidden messages in theatrical works in Vanishing Sensibilities: Schubert, Beethoven, Schumann (New York, 2012), 12–17. She also considers possible expressions of rebellion in Schubert’s opera on a text by Franz von Schober, Alfonso und Estrella (22–26). Her idea that the tyrant Mauregato may represent Metternich, as their names both begin with “M,” suggests how cautious artists were in that milieu. An 1823 play by the important Volkstheater playwright J. A. Gleich, Der Leopard und der Hund, was much more direct and bold in referring to Metternich—but after the royal family attended a performance, the play disappeared from Vienna. See Theaterzeitung, 4 December 1823, supplement no. 145, between pp. 581 and 582, and 23 December 1823, 619. Another Volkstheater example that demonstrates how it was possible to challenge the authorities is the piece known as Das beliebte Quodlibet from Gleich’s 1826 play Der Eheteufel auf Reisen. In this piece, the texts of selected musical snippets continually emphasize the need for silence because of the constant danger of police intervention. This work is reprinted with commentary in Lisa Feurzeig and John Sienicki, Quodlibets of the Viennese Popular Theater (Middleton, WI, 2008), xx–xxi and 275–84.

12. Otto Erich Deutsch, Schubert: Die Erinnerungen seiner Freunde (Leipzig, 1957), 199; my translation. Bauernfeld’s article “Einiges über Franz Schubert” is supposed to be from 17 and 21 April 1869, but I was unable to find it in an online version of Die Neue Freie Presse, so those dates may be incorrect.

13. This was the first adaptation that Perinet and Müller made together during the 1790s of the plays of Philipp Hafner (1735–1764); it is a reworking of Hafner’s play Der Furchtsame. They eventually turned all eight of Hafner’s complex morality plays into musical comedies.

14. More specifically, it is frequently categorized as a student song, which implies that it found a willing public among university students. For example, it is found on a German recording of student songs performed by student groups, Studentenlieder, Sonia, 77198 (1993).

15. Steblin, Die Unsinnsgesellschaft, 263. Steblin presents evidence that Schubert was involved with the Nonsense Society at precisely the time when the 4 December 1817 issue of their journal, Archiv des menschlichen Unsinns, appeared (22–24).

16. See Feurzeig and Sienicki, Quodlibets.

17. The other two central playwrights of the day were Josef Alois Gleich and Carl Meisl.

18. Franz Schubert in seinen Klaviersonaten (Leipzig, 1927), 24–25. Költzsch uses the connection to Aline to argue against the then-accepted view that Schubert had written the fantasy in 1820. Interestingly, he also refers to this as “one of the few definitely demonstrable cases in which Schubert took melodies directly from the then inexhaustible Viennese ground of the people” (25). This comment suggests that Költzsch found it reasonable to believe that there were many other such cases that were less easily proven.

19. Maurice Brown argued against this link, pointing out that Schubert never labeled the fantasy with a name. Though he acknowledged the presence of a musical reference to Der Wanderer in the slow movement, he was uncomfortable with interpretations that then expanded this idea by associating the whole work with the sentiments in those poetic lines. See Brown, Schubert: A Critical Biography (London, 1958), 124–25. Nevertheless, others have continued to make this association, and Susan Wollenberg recently argued that this piece “shows Schubert creating a profound reflection on the song of that name in the variations at the work’s centre” and even more broadly that “like the ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy, the chamber works featuring a variations movement based on a pre-existent Lied treat this not simply as an added element inserted into the movement cycle, but as a generative force for the whole work.” See Schubert’s Fingerprints: Studies in the Instrumental Works (Aldershot, 2011), 213–14.

20. Robert Darnton comments on the links between philosophy and eroticism in literature of this period in The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France (New York, 1996). See in particular chapter 3, “Philosophical Pornography.”

21. Aside from those discussed in the main text, other versions included a ballet at the Paris Opéra in 1766, adapted by Michel-Jean Sedaine; Aline, reine de Golconde by J. A. P. Schulz (Rheinsberg, 1787), later adapted and very popular in Denmark as Aline Dronning i Golconda; Aline, reine de Golconde by Boieldieu (St. Petersburg, 1804); Alina, regina di Golconda by Donizetti (Genoa, 1828); and Franz Berwald, Drottningen av Golconda (Stockholm, 1864–65).

22. The Viennese quodlibet took various forms. Most common was a single musical number, usually but not always within a Volkstheater play, in which several preexisting musical pieces were quoted in short snippets, with surprise and disjunction being important aspects of the genre. A quodlibet play was a whole play in which entire musical numbers from preexisting works were borrowed. In both types of quodlibet, the text of the original could be left as is or changed to suit the dramatic situation. John A. Rice discusses some interesting examples that were performed at the Imperial court, including a quodlibet commissioned for Emperor Franz’s name day in 1805 by his wife. See Empress Marie Therese and Music at the Viennese Court, 1792–1807 (Cambridge, 2003), 132–40. The humor of quodlibets clearly depended on the audience’s recognition of the quoted material to be effective, so these works inform us about what music was known by their intended audiences. The very existence of the quodlibet also shows how significant the practice of quotation was in Viennese cultural life, supporting the broader points of this essay. For the Vogl duet, see the edition of Rochus Pumpernickel in Feurzeig and Sienicki, Quodlibets, 90–97 and 288–89.

23. Deutsch, Schubert Reader, 141–42.

24. Otto Rommel reprinted the play in his Alt-Wiener Volkstheater, 7 vols. (Vienna, Teschen, Leipzig, 1917), 5:81–165; in this version, the duet has five stanzas. In one publication of sheet music—Sammlung komischer Theater-Gesänge no. 21 (Vienna, ca. 1822)—there are three stanzas, two almost identical to the reprint and another that includes lines from two other stanzas in the reprint. In another sheet music version, clearly printed several years later as there is a note by Bäuerle referring to his 1826 edition, there are three stanzas, once again with words reordered and stanzas recombined. I have also found reference to a version of the duet printed by C. G. Förster in Breslau in 1822, in which the text opens “Wie gehts denn bei Liebichs,” referring to a famous Breslau landmark; presumably the text of the play was altered so that Aline comes from Breslau rather than Vienna.

25. The misspelling of Kahlenberg, a mountain just north of Vienna, could reflect dialect pronunciation or could be evidence that this version was printed outside Vienna.

26. This is from the post-1826 printing.

27. There is much to be said about the keen awareness of the Volkstheater shown by both Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Richard Strauss in Der Rosenkavalier. For example, they deliberately quoted the Aline duet. In Act 1, rehearsal number 219, at the moment when various merchants are showing their wares to the Marschallin, the Marchande de Modes announces that she has “Le chapeau Paméla, La poudre à la reine de Golconde.” (The Pamela hat, Queen of Golconda powder). The upper line in the orchestra at this moment plays the pitches B–E–D♯–F♯–A, forming exactly the same intervals as the beginning of the refrain to Müller’s Aline duet, while omitting repeated notes. The vocal melody is not identical, but it opens with B–E–E, adding the element of repetition that the orchestra has omitted. Strauss’s quotation creates an interesting anachronism, as the opera is set “in the early years of the reign of Maria Theresia”—that is, in the 1740s, even before the original literary work had been written and about eighty years before the Müller-Bäuerle theatrical version. See Strauss, Der Rosenkavalier, piano-vocal score (London, 1985), 3, 98.

28. Orel, Ferdinand Raimund, xviii–xxi.

29. Deutsch, Schubert Reader, 580. Franz von Hartmann describes a gathering at the Anker, with a list of various people who were there. The list includes the Spauns (not identified any more clearly), who had just attended the play, and also Schubert.

30. Wilhelm Zentner, in the afterword to Raimund, Der Bauer als Millionär (Stuttgart, 1952), 83; my translation. Zentner also lists German cities where the play found acclaim: Munich, Leipzig, Berlin, and Hamburg.

31. Ibid.

32. Raimund, Der Bauer als Millionär, 67–68.

33. This is shown, for example, in a performance from the Salzburg Festival of 1988 that is available on DVD, Arthaus Musik, 101 836. As explained in the accompanying notes by Werner Thuswaldner, the added stanzas in this production had to do with controversies about fighter planes, sex education, and television programming (10).

34. The text of the added stanzas is given in Fritz Brukner, ed., Ferdinand Raimund in der Dichtung seiner Zeitgenossen (Vienna, 1905), 63–64. It ends as follows: “Wer solches hat erstrebt, / Hat nicht umsonst gelebt. / Kein Aschen!” (Whoever has striven for this / Has not lived in vain. / No ashes!) Brukner specifies that the verses were sung by “Hrn. Weiß” (v), and I assume this was Eduard Weiß, who played some of Raimund’s roles when he was performing elsewhere.

35. Specifically, Susan Youens writes of “a broadly arching, symmetrical phrase that seems a musical metaphor for awakening, ascending to heights of joy, and then descending to disillusionment.” Retracing a Winter’s Journey: Schubert’s “Winterreise” (Ithaca, NY, 1991), 237.

36. Ibid., 237–38.

37. Such arguments are sometimes employed regarding Schubert’s compositional process for strophic songs; if the melody fits one stanza particularly well, then Schubert was probably composing it with that stanza in mind. For example, in the song Des Fischers Liebesglück (D933), the octave leaps are particularly well suited to the text of the final stanza.

38. We have no specific reference to this play in the Schubert documents. However, both Bauernfeld and J. (presumably Josef) Kupelwieser wrote poems about Raimund. Kupelwieser’s was published in the Theaterzeitung on 18 March 1834 after the performance of Raimund’s Der Verschwender, and Bauernfeld wrote his in response to Raimund’s death in 1836. Bauernfeld’s poem appears to refer to Die gefesselte Phantasie along with the myth of Prometheus in the final stanza: “Angeschmiedet war der Dichter / An den Fels Melancholie, / Und ein Geier fraß das Herz ihm, / Riesen-Geier: Phantasie.” (Fettered was the poet / To the rock Melancholy, / And a vulture ate his heart, / The giant vulture Fantasy.” These are reprinted in Brukner, Ferdinand Raimund in der Dichtung seiner Zeitgenossen, 32–33 and 69–70.

39. For other recent writings on this piece, see Frank Samarotto, “Intimate Immensity in Schubert’s The Shepherd on the Rock,” in Structure and Meaning in Tonal Music: Festschrift in Honor of Carl Schachter (Hillsdale, NY, 2006), 203–23; and Till Gerrit Waidelich, “‘Der letzte Hauch im Lied entflieht, im Lied das Herz entweicht!’ Varnhagens Nächtlicher Schall als letzter Baustein zum Hirt auf dem Felsen,” Schubert: Perspektiven 8 (2008): 237–43.

40. Musical aspects of several of Berg’s works, including the Lyric Suite, the Violin Concerto, and Wozzeck, have been linked to the composer’s close friendships and secret love affairs. See Douglas Jarman, “Alban Berg, Wilhelm Fliess, and the Secret Program of the Violin Concerto,” in The Berg Companion, ed. Douglas Jarman (Boston, 1989), 181– 94 and Douglas Jarman, “Secret Programmes,” in The Cambridge Companion to Berg, ed. Anthony Pople (Cambridge, 1997), 167–79.

41. See, among many examples, Susan Wollenberg, Schubert’s Fingerprints; Richard L. Cohn, “As Wonderful as Star Clusters: Instruments for Gazing at Tonality in Schubert,” 19th-Century Music 22/3 (Spring 1999): 213–32; and Su Yin Mak, “‘Et in Arcadia Ego’: The Elegiac Structure of Schubert’s Quartettsatz in C minor (D703),” in The Unknown Schubert, ed. Barbara M. Reul and Lorraine Byrne Bodley (Aldershot, 2008), 145–53.

42. See, among many examples, Susan Youens, Schubert’s Poets and the Making of Lieder (Cambridge, 1996); Marjorie Wing Hirsch, “Mayrhofer, Schubert, and the Myth of ‘Vocal Memnon,’” in Reul and Bodley, The Unknown Schubert, 3–23; and Xavier Hascher, “‘In dunklen Träumen’: Schubert’s Heine-Lieder through the Psychoanalytical Prism,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 5/2 (2008): 43–70.