Schubert’s Freedom of Song, if Not Speech

KRISTINA MUXFELDT

For Richard Kramer

In these pages I wish to probe the freedom imagery in a surprising number of Franz Schubert’s songs, some written in the heady atmosphere of the so-called Befreiungskriege, the “wars of liberation” of 1813 to 1815, others composed only over the following decade, in the reactionary police state that Austria had become. Because the political dimension is more transparent in poetry from the earlier time I will first turn our attention to Schubert’s settings of several poems by Theodor Körner (1791–1813), the poet of German patriotism who took up arms in the wars against Napoleon and died a martyr for that cause in August 1813 at the age of twenty-one. Then we will take a closer look at Schubert’s continued preoccupation with similar imagery in songs set after the war to poems by Johann Mayrhofer and Johann Gabriel Seidl—this in the face of Austria’s by-then firm stand against a constitutional Vaterland for its people.

Schubert produced his Körner settings toward the close of an era when dozens of other composers, most prominently Beethoven in Vienna, openly addressed current affairs of state in celebratory songs and occasional music—a striking contrast with opera, which frequently took a longer, and more critical, historical view.1 Patriotic lyrics flooded the marketplace during those years, helping to drum up support for the war effort. This is not to say that opinion was uniform, though, since all publications were closely monitored—for civility of discourse as well as for political conformity. One surprisingly personal invective against the self-crowned emperor of the French with whom Austria earlier had tried to forge an alliance by political marriage (in 1810) was an ironic “Ode to Napoleon” attributed to the German poet, librettist, playwright—and diplomat—August von Kotzebue (1761–1819). It appeared anonymously in Moscow (not even the publisher was identified). As the “Genius of Freedom” weeps in slavery’s chains, he laments elegiacally before building to a mocking tirade: “Let thousands go to ruin, suffocated by hunger, plague, and sword; Just so that Your flags wave victorious, and nothing disturbs Your plan. Inhuman tiger [entmenschter Tyger] all the world calls you! Defiling swindler of trust and belief! No matter, You alone are victor! That goal is worth any means.”2

True, some people vacillated between admiration (perhaps rivalry) and disdain for Napoleon, yet whatever their thoughts on the intense German-national chauvinism that sprang up in reaction to French imperialism, or their loyalties or antipathy toward the old monarchies, everyone in Napoleon’s path felt the military threat and economic burdens of foreign occupation; commodity and food shortages, troop quartering, plunder of artworks and other property, and heavy taxation were common complaints. During this chaotic period the restless Körner, a native of Dresden, bounced from university to university, first expelled for his involvement in political-gang skirmishes while a student of the law in Leipzig, next a student of history and philosophy in Berlin, until his record began to catch up with him.

In August 1811 Körner moved to Vienna, where he sought out the Prussian ambassador Alexander von Humboldt (brother of the linguist, Wilhelm) and Friedrich Schlegel, and swiftly gained a position as a court poet following a number of successes as a playwright and librettist. He received competing offers from Count Pálffy at the Theater an der Wien and Prince Lobkowitz at the Burgtheater. Josef von Spaun introduced him to Schubert at a performance of Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride, after which the teenaged composer and the poet, six years older, bonded over their mutual admiration for the singers Johann Michael Vogl and Anna Milder. Körner seemed to be putting down roots in Vienna—he became engaged to the local actress Antonie Adamberger; yet in March 1813 he enthusiastically answered Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia’s call for volunteers to free his homeland from Napoleonic occupation.3 (Austria, with its dynastic ties to the French Emperor, would enter the coalition against Napoleon only in August.) Körner joined the elite Lützow Freikorps also known as the Lützower Jäger (hunters), a specially skilled unit that drew into its ranks a number of academics and writers as well as workers, tradesmen, and even women. Among his cohorts was the soldier Eleonore Prochaska, who successfully maintained her disguise as a man until she fell in battle in early October, 1813. Her story, a variation on “don’t ask don’t tell,” was celebrated in an 1815 play titled Leonore Prohaska, written by Friedrich Duncker, a Prussian delegate at the Congress of Vienna; Beethoven supplied incidental music for it. Hopes ran high among many of the young volunteers, Kriegsfreiwillige, that their patriotic sacrifices would bring about a genuine citizenry, the foundation for a German nation based on constitutional principles. So long as military enrollees were still needed, the authorities did little to dispel their enthusiasm, and martyrdom of writers such as Körner, who was killed in battle in mid-August, only aided in recruitment.

The war had galvanized the German nationalist movement and for a short time patriotic sentiment was directed against a common foe. This unity masked the dissatisfactions and widening political rifts within and between the German states and the Austrian Empire (its diverging emphases owing to the intricacy of the Empire’s ties to Rome and, like the Catholic Rhineland, to France). At stake were the role of monarchy, demands for constitutionalism, and basic questions of national identity and unity: who was the “we” mobilizing against “them”?

Those cracks in Austro-German political unity were not about to close with Napoleon’s defeat. And so, in the decade after 1815, authorities in the Austrian Empire, the kingdom of Prussia, and in other German monarchies broke the links to the nationalist movement that they had cultivated in the last years of the Napoleonic era.4 Hopes of the German nationalists and of all in Europe who aspired to independent nationhood were betrayed when the Congress of Vienna met after Napoleon’s defeat to reapportion Europe among the major powers—the old empires and monarchies. Under the auspices of Prince Clemens von Metternich the Restoration government ruled with an iron hand, aggressively suppressing all nation-oriented patriotic sentiment in central Europe: Vaterland was to mean only “land of the Father, the Habsburg emperor.” This effort to turn back the hands of time to a pre-revolutionary—even pre-Josephinian—world order notably included “the reenactment of Jewish disabilities that had been somewhat relieved in Napoleonic times,” as Jeffrey L. Sammons gingerly puts it, and a drastic tightening of the restrictions on free speech.5 Joseph II had loosened these in the early 1780s and also promoted religious tolerance for practitioners of minority faiths and for the growing community of Freemasons. After the March 1819 murder in Mannheim of August von Kotzebue by the radicalized student Karl Ludwig Sand, who believed the former liberal, then emissary to Russia, was spying on nationalist groups, the Carlsbad Decrees were issued. Among the new measures were restrictions on student travel from or into Austria to stifle contact with the German, Bohemian—and soon after, Italian—nationhood movements that threatened absolutist Imperial rule; the 1821 Greek war of independence from the Ottoman Empire sparked similar fears.6 Reactionary government officials were quick to label extremist any opposition whatsoever and sought to rehabilitate and oversee all those they could not expel (sometimes by enlisting them as censors).7 In James J. Sheehan’s spirited formulation, “Metternich saw Sand’s murder of Kotzebue as a godsend. In July 1819 he rushed to Teplitz where Frederick William was on holiday and repeated his insistence that a representative constitution was merely the first step on the road to revolution.”8 The following year the Vienna Schlussakte would affirm the principle of Imperial autocracy. Spies infiltrated daily life, books were confiscated, and an army of bureaucratic censors, some reluctant, went to work crossing out whatever hints they could find of seditious sentiment. Within a few years’ time Vienna’s chief of police Josef Sedlnitzky could dismiss as fanatical Hirngespinste—“phantoms of the mind”—those dangerous visions of “citizenry and a system of representation”9 promulgated by the poet Johann Senn (1795–1857), one of Schubert’s friends from his Stadtkonvikt days. The police chief’s language echoes the preamble to the 1810 censorship code, thought to have been written by Friedrich von Gentz (later Metternich’s trusted advisor):

No ray of light, from wherever it may emanate, shall in future remain unrecognized or unacknowledged in the Monarchy or shall be hindered from realizing its potential usefulness; but with a careful hand the hearts and minds of minors shall be protected from the corrupting misbirths of hideous fantasy, from the poisoned breath of self-serving seducers/ corrupters [Verführer], and from the dangerous mental webs [Hirngespinsten] spun by twisted minds.10

The talent in all social classes was to be channeled to serve the interests of the state, and by the 1820s language crafted to denounce the sexual exploitation of youth was just as easily turned against anyone who opposed absolute monarchy. Metternich’s government discovered dangerous new enemies of the state on the flip side of the Napoleonic coin and panicked that local nationhood supporters might follow Sand’s lead. Instead of dying on the battlefield as Körner had, Senn would endure a different form of sacrifice, finding himself imprisoned without due process for fourteen months in the city he called home before being expelled permanently from Vienna in the spring of 1821.11

The political leanings of Schubert and his friends may be construed as an Austrian version of what Christian Jansen calls “oppositional nationalism”: in the wake of the victory against Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15, European heads of state buttressed the monarchies and redrew the map of Europe, creating institutions of “the German nation,” including the German Confederation and its bodies. “However, the liberal and democratic opposition perceived these organizations merely as a new foreign rule, which had its center in Vienna instead of Paris. Compared with the cases of western or northern Europe, oppositional nationalists in the German lands scarcely identified themselves with the institutions of the state, particularly after the Prussian Reforms and Carlsbad Decrees of 1819.”12 Jansen highlights three peaks in the “waves” of what he terms “organized nationalism” that rose to public (open) expression in Germany, spreading from the academic elite into the wider cultured bourgeoisie: 1812–19, 1830–32, and 1848–49.13 The first two periods essentially bookend Schubert’s compositional career. These peaks are bounded on one side by the crackdown on free speech, travel restrictions, and other measures enacted in Carlsbad, and on the other side by the 1830 July Revolution in France (which placed Louis-Philippe I on the throne, whose father, the Duke of Orléans, had actively supported the 1789 Revolution before he became a casualty of the Terror) and the 1832 Hambach Festival in the Rhineland. More localized energies form a counterpoint of smaller peaks and troughs. During the mid-1820s, for example, the Mühlviertel in Upper Austria was believed to be “on the eve of a revolution.”14 In Linz and Vienna during 1825 and 1826 the authorities also feared trouble.15 Moreover, limitations on free speech were publicly tested with increasing frequency, even in the theaters, if only to shame the enforcers.16

From Teutomania to Songs of Sunrise

One eloquent witness deserves to be heard here, although the scenes Heinrich Heine recalls happened at some distance from Vienna. What emerges with such clarity in Heine’s 1840 recollections is that a broad-spectrum shift in the trajectory of conversations around German nationhood took place precisely over the span of Schubert’s compositional career. Heine opens book four of Ludwig Börne: A Memorial with some impressions contrasting the political temper that prevailed at the October 1817 Wartburg Festival in Thuringia—where several hundred fraternity students, Burschenschafter, commemorated the decisive 1813 Battle of Leipzig,17 assembling at the castle where Martin Luther had translated the Bible—and the “fundamentally different spirit articulated in Hambach” fifteen years later. Whereas “the specter that spooked around on the Wartburg” was a “narrow Teutomania,” at the Hambach celebrations in May 1832 “the modern age jubilated in songs of sunrise and drank the pledge of eternal friendship with all mankind…. French liberalism delivered its most intoxicated Sermons on the Mount, and even if many irrational things were said, still reason itself was recognized as the highest authority.” A vivid memory of the earlier time follows: “In the beer cellar at Göttingen I used to have to admire the thoroughness with which my Old German friends created their proscription lists for the day when they would come to power. Whoever descended in the seventh generation from a Frenchman, Jew, or Slav was to be condemned to exile. Whoever had written the least thing against, say, Jahn or any Old German absurdities could prepare himself for death.”18 As disagreeable as the blinkered colluding of these “Old Germans” had been, Heine found it more disquieting that in the heat of the July Revolution “many of these Teutomaniacs, in order to take part in the general movement and the triumphs of the spirit of the times, forced themselves into our ranks, the ranks of the fighters for the principles of the revolution.”19

Heine’s reference to “the general movement and the triumphs of the spirit of the times” describes a majority, with the extremists safely bracketed. All the various factions opposing the state would have fought side by side for nationhood, this much Heine granted, but he brooded that the old opposition, fixated on German Nazionalität (national identity), still outnumbered the cosmopolitans in the new liberal opposition. The Deutschthümler—easy to identify in the aftermath of the wars of liberation because back then they paraded their Germanness in the cut and color of their clothes, their mannerisms and speech—underwent political conversions or, more troubling, merely masqueraded as liberal revolutionaries.20 We can add to these considerations that because the Prussian regime had cultivated ties to nationalist groups during the war their rhetoric was able to spread throughout the coalition, exerting an influence on official forms of patriotism within the Austro-German confederation as well as on the opposition. After all, visitors affiliated with the Congress of Vienna had increased the city’s population by nearly a third, and ideological arguments, reading matter, and local talk traveled with them (some 100,000 visitors flooded into the city for the Congress).

Heinrich Heine’s is only one voice, yet the unsettling mutability of political allegiances he observed is something we can also expect to see signs of elsewhere. It certainly surprised him to find that in Berlin in 1822 the songs of Theodor Körner, once taken up by patriotic choral and gymnastic societies, still could be heard (many of the poems were designed to be sung to familiar chorale melodies). In the third of the Letters from Berlin he tells of an anniversary party at which Körner’s “Schwertlied” was performed by twelve young women. “As you can see, Theodor Körner’s poems are still sung here. Naturally, not in circles of good taste: in these it is already said openly how fortunate it was that in 1814 the French could not understand German, and so could not read these bland, shallow, flat verses devoid of poetry that made us good Germans wax so enthusiastic.”21 Regrettably, Heine left no dispatches from Vienna to help us gauge the rise and fall of political temperatures in the diverse strata of society there. He did, however, compose an estimation of Austrian official politics in a preface to the 1832 Letters from Paris:

Austria was ever an open and honest enemy, which never denied, nor did it for a moment suspend its attack on Liberalism. Metternich never ogled with loving eyes the Goddess of Liberty; he never played the demagogue with troubled anxious heart; he never sang the songs of Arndt while drinking white beer; he never played at gymnastic exercises on the Hasenheide; he never played the pietist, nor did he ever weep with the prisoners of the fortresses while he kept them chained…. He acted magnanimously in the spirit of a system to which Austria had been true for three centuries.22

1815: The Lyre of a Patriot

Theodor Körner’s poetry appeared in two significant collections in the years immediately following his death: Leyer und Schwert (Lyre and Sword) was published in 1814 and a two-volume Nachlass edition appeared in 1815. Schubert set over a dozen poems of Körner that year along with a one-act opera, Der vierjährige Posten (The Four-Year Sentry Duty), about a military deserter who escaped prosecution for treason by claiming it was he who had been abandoned four years earlier; he’d never left his post. Körner’s poetry attracted many composers at this time, but Ilija Dürhammer speculates that Schubert was inspired to make his settings only after meeting Johann Mayrhofer (1787–1836), an ardent admirer of Körner.23 This would be interesting, if true, because both Mayrhofer’s and Senn’s names appear on a watch list of a dozen Burschenschafter in Vienna, as Ruth Melkis-Bihler reports in her admirable overview of Schubert’s political times. She notes that this was a very small cohort compared with fraternity membership lists from German university towns, suggesting that they were closely overseen. In fact, more of Schubert’s friends and acquaintances appear on this list than Melkis-Bihler conveys.24 Mayrhofer was a decade older than Senn or Schubert and by 1815 he had accepted the censor’s post that would become a source of inner conflict for the rest of his life, which ended dramatically in 1836 when he leapt to his death from the censorship building. Notably, his position did not prevent his 1817 Beyträge zur Bildung für Jünglinge from being banned after two issues. (See the selections from this collection of poems, essays, and aphorisms devoted to the civic education of youths, introduced by David Gramit, in this volume.) From the fall of 1818 to the end of 1820 Mayrhofer and Schubert shared the same rooms on the Wipplingerstrasse formerly occupied by Körner.

Interspersed throughout the Körner collections are poems of youthful passion for a girl, and ones extolling battle and the yearning for an ideal. The ideal, like the girl, is named only indirectly: “Die Liebe”—words that can mean simply “love,” the emotion, or can be treated as a name, pointing to a particular beloved “die Liebe,” “the beloved one,” or even to a personification of love. Telling apart the intended referents can be challenging because both kinds of poems speak of Sehnsucht (yearning), of “sweet lights,” of hope, and elevated strivings. Sometimes the ideal Liebe is figured as a bright star in the heavens whose appearance signals a rosy dawn, the spring of a new age. If that symbolism seems an obvious political cipher, it is useful to consider the cognate in Goethe’s memorable epithet “ein rosenfarbnes Frühlingswetter” (a rosy-colored spring weather) for the dewy flush that forms on the satisfied lover’s face.25 Far less skillfully than Goethe but striving for a similar tone of mystery, Körner worked images of glowing heavenly brides into both his political canvases and his poems forecasting domestic bliss. (Heine disliked his simple rhymes on technical as well as ideological grounds.) Indeed, the deeper we read into Körner’s collection the harder it is to separate confidently the two categories of poems: a pervasive religiosity colors any sensual or political reading. Compare the opening lines of Der Morgenstern (D172, D203, in seven stanzas), a hymn to Venus, the morning star—

Stern der Liebe, Glanzgebilde, |

Star of love, radiant image, |

Glühend wie die Himmelsbraut |

glowing like the bride of heaven, |

Wanderst durch die Lichtgefilde |

you wander through the realm of lights |

Kündend, daß der Morgen graut. |

heralding the morning gray. |

—with the opening stanzas of Sängers Morgenlied (D163, D165, six stanzas), in which a sweet light breaks triumphantly through the night and love’s gentle wafting in the breezes, as translated below, though it could just as well be the Beloved (Freedom) swaying in the breeze, swells the poet’s heart as he greets the roseate splendor of the dawn. Speaking in either metaphor, the language is secretive, whether we hear private intimacies expressed or whisperings of political hope.

Süßes Licht! Aus goldnen Pforten |

Sweet light! Through golden portals |

Brichst du siegend durch die Nacht. |

you break victoriously through the night. |

Schöner Tag! Du bist erwacht. |

Glorious day! You have awakened. |

Mit geheimnisvollen Worten, In melodischen Accorden Grüß’ ich deine Rosenpracht! |

With mysterious words, in melodious strains I greet your roseate splendor! |

Ach! Der Liebe sanftes Wehen |

Ah, love’s gentle breezes |

Schwellt mir das bewegte Herz, |

make my moved heart swell |

Sanft wie ein geliebter Schmerz. |

as softly as a beloved pain. |

Dürft ich nur auf gold’nen Höhen |

If only upon golden heights I might |

Mich in Morgenduft ergehen! |

bask in morning fragrance! |

Sehnsucht zieht mich himmelwärts. |

Yearning draws me heavenward. |

In this excerpt, from a lengthy patriotic poem in Leyer und Schwert not set by Schubert, “Was uns bleibt” (All that remains for us), a star’s identification with political freedom is made explicit:

Wenn auch jetzt in den bezwung’nen Hallen |

Even though now in vanquished halls |

Tyrannei der Freiheit Tempel bricht; — |

tyranny breaks Freedom’s temple; — |

Deutsches Volk, du konntest fallen, |

German people, you could fall, |

Aber sinken kannst du nicht! |

but sink under you cannot! |

Und noch lebt der Hoffnung Himmelsfunken. |

The heavenly spark of hope lives on. |

Muthig vorwärts durch das falsche Glück! |

Courageously onward through false fortune! |

‘S war ein Stern! Jetzt ist er zwar versunken, Doch der Morgen bringt ihn uns zurück. ‘S war ein Stern! —Die Sterne bleiben. ‘S war der Freiheit gold’ner Stern. 26 |

‘Twas a star! Though he has now faded the morning shall return him to us. ‘Twas a star! —The stars remain. ‘Twas Freedom’s golden star. |

Körner’s poems about death in battle revel in wedding imagery, notably so in “Schwertlied,” which draws out what today seems a ludicrous metaphor into a sixteen-stanza conversation between a soldier and his sword (its stanzas are in quotation marks). The dialogue promises young men an experience in battle as intense as the wedding night. The soldier’s sword is his beloved bride and the performers in Schubert’s setting for a unison chorus and solo voice are instructed to clink swords on those sixteen “hurrahs,” just as Körner indicated in a footnote, making a communal racket as noisy as the traditional breaking of porcelain at a Polterabend, the festivities on the eve of a wedding. Did Schubert find this absurd or did he take it seriously?

Schwertlied (D170, stanzas 3, 4, and 12):

Ja, gutes Schwert, frey bin ich, Und liebe dich herzinnig, Als wärst du mir getraut, Als eine liebe Braut—urrah! |

Yes, my good sword, I am free, and love you dearly as if you were my betrothed, as if my sweet bride—Hurrah! |

Zur Brautnachts Morgenröthe Ruft festlich die Trompete; Wenn die Kanonen schreyn, Hol’ ich das Liebchen ein.—Hurrah! |

The festive trumpet heralds the bridal-night’s rosy morn; when the cannons shriek, I shall catch up to my dearest.—Hurrah! |

…………………. |

………………….. |

“Ach herrlich ist’s im Freyen, Im rüst’gen Hochzeitsreihen Wie glänzt im Sonnenstrahl So bräutlich hell der Stahl!”—Hurrah! |

“How glorious to be in open air, in a wedding round so hale, where the sunlit steel gleams like bridal white!”—Hurrah! |

Even an apostrophe to the beloved so innocently pious as “Liebesrausch” (Love-Intoxicated) invites political reading when it is found amid these martial poems. The use of the diminutive Mädchen at first masks that this rapturous poem might sing of the ideal—for Susan Youens it is a love poem that “does not rise much above the level of platitude”27—but what eventually strikes our ears are the endings of each stanza and the narrowing of focus in the last verse: at the close of the first stanza, “your noble image shines for me”; at the end of the second, “and all my loveliest songs name only you”; and the third, with Körner’s emphases, “Only one longing lives in me, only one thought here in my heart: the eternal quest for you.” As with several Körner poems, Schubert attempted two settings (D164 and D179, in March and April 1815).

Here is the entire poem, “Liebesrausch”:

Dir, Mädchen, schlägt mit leisem Beben Mein Herz voll Treu’ und Liebe zu. In dir, in dir versinkt mein Streben, Mein schönstes Ziel bist du! Dein Name nur in heil’gen Tönen Hat meine kühne Brust gefüllt; Im Glanz des Guten und des Schönen Strahlt mir dein hohes Bild. |

For you, maiden, my heart pounds, a quiet trembling of devoted love. In you, in you my striving ceases; you are my life’s fairest goal. Your name alone, a sacred tone, fills my bold breast. In the radiance of all that’s good and beautiful your noble image shines for me. |

Die Liebe sproßt aus zarten Keimen, Und ihre Blüthen welken nie! Du, Mädchen, lebst in meinen Träumen Mit süßer Harmonie. Begeist’rung rauscht auf mich hernieder, Kühn greif ich in die Saiten ein, Und alle meine schönsten Lieder, Sie nennen dich allein. |

Love [the Beloved] sprouts from tender seeds, and its [her] blossoms never wither! You, maiden, live in my dreams in sweet harmony. Rapturous inspiration comes over me, boldly I pluck the strings, and all my loveliest songs, they name only you. |

Mein Himmel glüht in deinen Blicken |

My heaven glows in your glances; |

An deiner Brust mein Paradies. |

my paradise upon your breast. |

Ach! Alle Reize, die dich schmücken, |

Ah! All the charms adorning you, |

Sie sind so hold, so süß. |

they are so noble, so sweet. |

Es wogt die Brust in Freud und Schmerzen, |

My breast undulates in joy and pain; |

Nur eine Sehnsucht lebt in mir, |

only one desire dwells in me, |

Nur ein Gedanke hier im Herzen: |

only one thought here in my heart: |

Der ew’ge Drang nach dir. |

eternal passion for you! |

Finally, Körner himself spelled out the ambiguity, conflating Liberty and Venus, in a poem titled “Abschied vom Leben” (Departure from Life) written on the eve of a near-brush with death three months before he finally succumbed in battle. By the poem’s end freedom and love can no longer be meaningfully distinguished:

And that which I knew to be sacred here, |

|

Wofür ich rasch und jugendlich entbrannte, |

for which quickly and youthfully I became enflamed, |

Ob ich’s nun Freiheit, ob ich’s Liebe nannte: |

whether I called it Freedom, or whether Love: |

Als lichten Seraph seh’ ich’s vor mir stehen— |

As luminous Seraph I see it standing before me now— |

Und wie die Sinne langsam mir vergehen, |

and as my senses slowly leave me, |

Trägt mich ein Hauch zu morgenrothen Höhen. |

a breath carries me to rosymorning heights. |

I do not wish to linger over Schubert’s Körner settings here, I merely wish to observe that a vocabulary of images found in his (and not only his) poetry from this time resounds through many other poems that Schubert chose to set in later years. This was one way around the ever stricter censorship restrictions that came in the wake of the Congress of Vienna. Heard in isolation, faint echoes of revolutionary freedom imagery might be easily dismissed by readers, or, for that matter, could be deliberately masked by poets.

The Death of Actaeon

Especially complex examples of such concealment of freedom imagery are found in poems of Johann Mayrhofer, the conflicted censor who maintained his oppositional, at times markedly Germanic liberalism while dutifully serving the state for twenty years. Schubert’s friend Josef von Spaun would later characterize him as “extraordinarily liberal, indeed democratic, in his views … passionate about freedom of the press.”28 Mayrhofer, in his own 1829 recollection of Schubert, hinted intriguingly at a deepening rift between the two intimate friends whose personalities had often clashed even while they lived together: “The cross-currents of circumstances and society, of illness and changed views of life kept us apart later, but what had once been was no more to be denied its rights.”29 Mayrhofer’s poetic oeuvre is steeped in classical literature and Greek mythology, often presenting familiar episodes with surprising twists or omissions. We can see this in the following poem about Diana, the goddess who roams the forests freely with her handmaidens. (Her father Zeus promised he would never force her to marry against her will.) Just when Mayrhofer wrote the poem “Der zürnenden Diana” is not known; Schubert’s song dates from December 1820, the final month of his stay with Mayrhofer (by which time their mutual friend Senn had already languished in prison for nearly a year and his fate was still uncertain).

Ja, spanne nur den Bogen, mich zu tödten, Du himmlisch Weib! im zürnenden Erröthen Noch reizender. Ich werd’ es nie bereuen, Dass ich dich sah am blühenden Gestade Die Nymphen überragen in dem ade, Der Schönheit Funken in die Wildniß streuen. |

Yes, draw your bow to slay me, you heavenly woman! in the flush of anger more enchanting still. I shall never regret that I saw you on the flowering bank, towering over the nymphs in the bath, spreading rays of beauty into the wilderness. |

Den Sterbenden wird noch dein Bild erfreuen. Er athmet reiner, er athmet freyer, Wem du gestrahlet ohne Schleyer. Dein Pfeil, er traf, doch linde rinnen Die warmen Wellen aus der Wunde; Noch zittert vor den matten Sinnen Des Schauens süße letzte Stunde. |

Your image will yet gladden the dying one. He who has beheld your unveiled radiance breathes more purely, more freely. Your arrow—it struck, yet warm waves spill gently from the wound. Still trembling before failing senses is the last sweet hour of sight. |

Der zürnenden Diana (Of Diana Enraged; D707) tells the familiar story from book three of Ovid’s Metamorphoses of the hunter Actaeon accidently stumbling upon the goddess bathing in a pool. Her virgin nymphs use their own bodies to shield her from Actaeon’s gaze, “but the goddess stood head and shoulders over all the rest,” as Ovid tells it “and red as the clouds which flush beneath the sun’s slant rays, red as the rosy dawn, were the cheeks of Diana as she stood there in view without her robes.” Diana, infuriated, gazes back at Actaeon, splashes him with water and robs him of his speech: “Now you are free to tell that you have seen me all unrobed—if you can tell,” she taunts him (how could a censor-poet not have noted this challenge?) and she makes horns sprout from his forehead so that his hounds will mistake him for a stag, the very prey they have chased all day. Unable to command the dogs as before, Actaeon will be torn to shreds by them.30

Figure 1. Titian, The Death of Actaeon.

In Ovid’s telling Diana is unarmed when Actaeon happens upon her, her quiver and her unstrung bow resting with one of her handmaidens. Not so in Mayrhofer’s poem, where Actaeon is struck by Diana’s arrow—as he is in Titian’s memorable portrayal of The Death of Actaeon (1559–75), which fixes forever the instant when an athletic, rosy-cheeked Diana, clad in a rose-colored tunic, has just let fly her arrow (see Figure 1). With her right arm still drawn back and her bow-arm outstretched one breast is exposed to the viewer, who inadvertently becomes a voyeur. We do not notice immediately that on the right, blended into the brownish thickets in the distance, a partly transformed Actaeon is being mauled by bloodthirsty hounds. The picture’s time scale is complex, more like a photographic double exposure than a single moment in snapshot. (Titian’s Diana, we might note, bears a striking resemblance to the equally unforgettable figure who strides across the battlefield in Eugene Delacroix’s 1830 canvas Liberty Leading the People. As Liberty holds high the tricolor flag, her flushed cheek and exposed breasts are illuminated by the blazing heavens; only gradually do we notice the dying Revolutionary at her feet hoisting himself up to catch a last glimpse of her. Buried in plain view in both canvases is the doomed beholder of an awe-inspiring female figure.) I do not know if Mayrhofer knew Titian’s work, either by reputation or in copy, but it is not unlikely. Until the early 1790s the Duke of Orléans owned Titian’s painting. In an effort to ride out the storm of upheaval in the late 1780s he had engraved copies produced of all his paintings before he offered his magnificent collection for sale. This series was printed between 1786 and 1808, interrupted for a time by the chaos of the revolution. The Duke, or Philippe Égalité as he was known, did not live to see his Titians and other masterpieces on display in London during the early years of the nineteenth century, where they were enthusiastically viewed by many. As a member of the royal family, in line for the throne, he was guillotined. The Congress of Vienna held extensive deliberations about the fate of artworks that had changed hands during the French Revolution and the First Empire. With the rise of public museums across Europe came questions not only about stolen artworks but about the status of royal art collections as personal or national property.31 Curiously, in the Mort d’Acteon found among the Orléans engravings Titian’s graceful Diana is made to appear remarkably masculine (see Figure 2).

In Mayrhofer’s “Der zürnenden Diana” all mention of the stag’s antlers and the hounds is left out, except, perhaps, for his choice of the verb zittert (trembles) in the penultimate line—“noch zittert vor den matten Sinnen”—evoking the convulsive shivers of the wounded animal as it expires. Other features in the poem leap out: the words “du himmlisch Weib,” because high esteem for any woman is a striking anomaly in this poet’s output. More significantly, Mayrhofer tells the story from the perspective of a defiant Actaeon (though not once named in the poem) who welcomes the fatal arrow, refuses remorse, and insists that the forbidden vision was worth dying for even as warm blood gushes from his wounds and his senses leave him. This stands in stark contrast to those Renaissance accounts of Ovid’s tale that present the wayward hunter as a hapless victim punished for his error by a tyrannical goddess who knows no mercy, at least not forgiveness. Man’s fortune can spiral out of control in an instant: this was one lesson for early modern observers of Parmigianino’s Actaeon frescos, for example, and the warning is still there in Titian.32

Figure 2. Jacques Couché, engraving based on Titian’s Death of Actaeon in the Gallery of the Palais Royal with historical commentary by the abbé de Fontenai.

Mayrhofer declares his radical remove from such traditional ecclesial and courtly interpretation in strophe 2, when the mythical hunter’s singular experience is generalized: he who has glimpsed the towering beauty’s rays scattered into the wilderness, who has seen her without her veils—he will breathe more purely, will breathe more freely. Rather than warning the viewer who gazes at a painted image of Diana’s nakedness not to repeat Actaeon’s error, the defiant hunter in this poetic fable invites emulation. “Er athmet reiner, er athmet freyer / Wem du gestrahlet ohne Schleyer”: the second er appears to have been added by Schubert to intensify the meaning; it does not appear in the text Mayrhofer published in 1824.33 About this stanza we might also speculate that the word Schleyer (veil), a rhyme for the adverb freyer (freely), could evoke a symbol—a Sinnbild—borrowed from a late eighteenth-century Masonic imaginary: the veils of Isis. The Egyptian nature goddess’s veils concealed mysteries that only her initiates could fathom.34

Mayrhofer’s stripped-down telling of Actaeon’s story makes possible rosy-cheeked Diana’s transferal from the realm of myth into the domain of Sinnbild (the German term, literally a “sense picture,” a pictograph), allowing her image to lend concrete shape to an abstraction. Yet it is Schubert’s absorbing music that actually lulls us into forgetting the mythic veil. Commentators on the song have remarked on the needless repetition of phrases in Schubert’s setting: words conveyed clearly the first time through are repeated over and over again. When we pay heed to the rhetoric of those repetitions to see what is emphasized thereby, what is downplayed, and how local harmonies, modulations, and dynamics color our perception of the words, we can appreciate how much greater the freedom of song is for releasing those symbolic associations that the compact poem cloaks in myth.

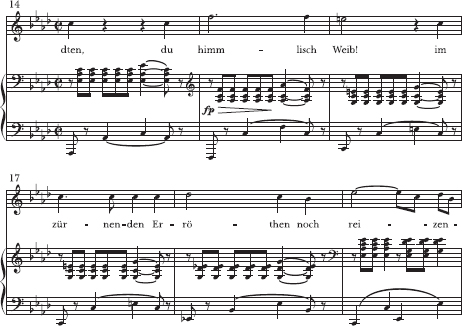

In Schubert’s ten-bar piano introduction to the poet’s words in Der zürnenden Diana there is already a hint of a poetic image, as yet inchoate, in the repeating figuration used to make a crescendo from piano to forte then pulled back to pianissimo just before the singer’s entry. From sharp fp attacks on the downbeats the quivering chordal triplets in the treble build to a climax in the accented middle of each bar. At the crescendo’s high point in measure 5 a diminished seventh thwarts a move to the relative minor, making the Feurig tremors shake yet more forcefully before the harmony veers around to a tonic cadence in A-flat major by way of a passing German augmented sixth on F♭. The coordination of tonal surge and dynamic swell draws our attention to an emerging form.35

Making bold, the singer begins—“Ja, spanne nur den Bogen mich zu tödten”—and once again the harmony bends to F minor and an arresting E♮ “promissory note”36 against the C♮ root of that key’s dominant, “Du himmlisch Weib” (see Example 1). On repetition, those words are inflected by the wondrous glow of F-flat major, I–V (the earlier leading tone now a root, and the melodic contour twisted to put C♭ into the outer voices). At play in the architecture of the song is basically a tension between the tonic-major and parallel minor modes: simply put, the relative minor, F minor, is a minor-mode adjunct to A-flat major (because its dominant sits a major third above A♭); F-flat major is a poignant major mode adjunct to A-flat minor (its dominant sits a minor third above A♭.). Much else intervenes, it needs hardly be said, but the reach of these combined harmonic and dynamic inflections extends all the way to the end of the song. For his portrayal of the cherished vision still trembling before the Sterbender’s eyes Schubert summons the strongest dynamic contrast yet, reinforced by the indications stark and leise in the vocal part, and colors the final closure in the tonic-major with a dab of F♭ as if the singer had not the strength to reach a semitone higher.

That Schubert’s song is addressed to Liberty, freedom personified—a multivalent image carrying political, sexual, even anarchic associations, and fast vanishing from open public discourse due to censorship—may be suggested in the exquisite harmonies enveloping “du himmlisch Weib” and in the threefold repetition of “im zürnenden Erröthen” that lays stress on the rosy hew in this aural canvas. Next repeated is “Ich werd’ es nie bereuen,” made even more emphatic when Schubert later repeats the declaration in this rewording: “Nie werd’ ich es bereuen, dass ich dich sah.” The place where Diana is first seen by Actaeon is indicated in a whisper, a pianissimo stream of rising and falling eighth notes: “am blühenden Gestade die Nymphen überragen in dem Bade” (on the flowering bank overtowering the nymphs in the bath). These are practically the only words in the song not to be emphasized by local repetition and further bracketed by crescendi carrying the thought through to its radiant goal. Consider that if the pianissimo words were cut away altogether, the sentence would remain perfectly coherent: “Nie werd’ ich es bereuen, dass ich dich sah, der Schönheit Funken in die Wildniß streuen” (Never shall I regret that I saw you, scattering Beauty’s rays into the wilderness). Schubert lets us hear the latter clause twice in soaring cadential phrases (four times if we count the weaker cadences to C-flat major in measures 46 and 50), bringing the first half of the song to a close in B major (Example 2). A temporal caesura is made by transforming this last root into a leading tone: from an isolated B♮ a downward arpeggio through a G-major dominant-seventh takes us to faraway C major where the action is paused and a narrating voice in sympathy with the wounded man avows that he breathes more freely now that he has been illuminated by Diana’s unveiled radiance. “Wem du gestrahlet ohne Schleyer” is heard four times, giving us ample chance to feel the scrim evaporate before our eyes. Twice the fatal arrow strikes its mark and the repetition in its wake creates something like a tableau vivant, an almost cinematic simulation of real-time dying: the narrating, now “autobiographical” voice clings to the radiant vision as his senses slowly leave him. The entire closing scene recalls Körner’s vision of a Lützower Jäger’s death on the battlefield: “Whether I called it Freedom, or whether Love: as luminous seraph I see it standing before me now; and as my senses slowly leave me a breath carries me to rosy-morning heights.” It takes little effort to hear this song as an elegy for a fallen comrade.

Example 1. Der zürnenden Diana, D707, mm. 14–30.

Paired in one Liederheft (a gathering of songs) with Der zürnenden Diana is another song on a Mayrhofer text, Nachtstück (D672), which Schubert dedicated to the singer Katharina von Lacsny, née Buchwieser. In the February 1825 publication announcement in the Wiener Zeitung the publisher Cappi took credit for the selection of the two songs in Opus 36: prospective buyers were assured that both had been well received in Johann Michael Vogl’s performances for the most select private circles.37 Surely Schubert approved the dedication and selection. The musicologist Clemens Höslinger has speculated that the song about Diana’s nakedness must have called up not only the beautiful “Catinka” Buchwieser’s many love affairs but also a scandalous naked orgy said to have been planned in November 1812 at Count Pálffy’s palace in Hernals. The police got wind of it and punished all the associates of the “Adamiten und Maurerloge.” (Since Vienna’s Masonic chapters were shut down two decades earlier, mention of an active lodge surprises almost as much as the pairing of Adamites with Freemasons.) The noblemen paid hefty fines; the women, including Buchwieser, were given a flogging, and then the poor singer had to appear onstage the next day as the Princess Navarra in François Adrien Boieldieu’s opera Jean de Paris.38 Quite possibly the dedication did invite such associations “in the most select circles”—or, worse, prompted performances meant to embarrass the singer, who was respectably married by the time Schubert composed the song.

Example 2. Der zürnenden Diana, D707, mm. 50–73.

Höslinger wonders further whether the 1869 picture of Diana in the Schwind Foyer at the Vienna Court Opera might be an homage to the former singer. The trompe l’oeil statue of Diana in the fresco by the Viennese painter and Schubert friend Moritz von Schwind (Figure 3) has just released her arrow, and her right arm is still pulled back, her bow arm outstretched, rather like Titian’s. A symbol of Luna, the crescent moon, often associated with Diana (as in Titian’s earlier Diana and Actaeon, another picture in the Orléans collection), adorns her head, and a thin shawl is snaked around her naked body. Since Schwind was introduced to Frau Lacsny by Schubert in 1825, the same year Schubert published and dedicated his Der zürnenden Diana to her, it seems reasonable to imagine that she was on his mind when he designed the tryptych portraying Diana along with other themes from Schubert’s works (also visible in Figure 3 is Goethe’s “Der Fischer”).

These suggestions are by no means mutually exclusive: to take the allusion to the former Catinka Buchwieser and the 1812 sex scandal at face value (not as a Schleyer for another political meaning) is only to acknowledge that sexual freedom, freedom from social convention, was an element in Schubert’s political credo. How entwined Restoration political agendas were with the regulation of private behavior is revealed by a later event. The right to privacy would not gain legal recognition for decades. But in March 1848, the year censorship restrictions were briefly lifted, the Wiener Zeitung announced that not only was censorship gone but the police would cease spying. Henceforth, invasive police intrusion into the private lives of the city’s residents was strictly forbidden.39 Whatever else we may imagine, the dedication to Lacsny extends to both songs in Opus 36, the Actaeon tale, Op. 36, No. 1, and the haunting Nachtstück, No. 2, composed in 1819. Both were published a half step lower than originally conceived, perhaps to accommodate a favorite singer. The subject matter of Nachtstück? When the fog descends and Luna does battle with dark clouds, “Der Alte,” the old rhapsode, takes his lyre and sings this apocalyptic prophecy into the forest: “Du heil’ge Nacht: bald ist’s vollbracht.”40 What shall be soon completed? “Soon I shall sleep the long slumber, and be released from all suffering.” The old man seems already to have lived for far too long, like old Tithonus, lover of Eos (the dawn), who grew aged but could not die. Luna’s name is the only overt hint, as in many Mayrhofer poems, of a mythological basis. The meaning of the song (and of the entire opus) changes depending on which Alter we imagine sings the prophecy “Holy Night: soon it shall be accomplished.” Is he Endymion, destined eternally to slumber in youthful beauty so that Luna may penetrate him on nightly visits, siring their many daughters? Or is he Tithonus, likewise granted longevity by his beloved Eos, in his case, however, in the form of old age? Tithonus is traditionally represented as a bard carrying a lyre or harp. The troubled, Baroque, C-sharp-minor counterpoint with which Schubert’s eerie tone-painting begins yields to blurred arpeggios created “with raised dampers” as the prophetic words are sung in a muted voice (gedämpft). Twice, novel deceptive cadences accentuate the words “old man,” then on the last page otherworldly harmonies sink mysteriously (the old man listens for Death), transforming the atmosphere for the C-sharp-major close. Moments before, the narrating voice relates that many a dear bird (mancher liebe Vogel) calls out, “Oh let the old man rest in his grassy tomb.” The fictional scene is punctured. No matter which old man came to contemporary listeners’ minds, this exhortation must have sounded like a very personal message when sung by Johann Michael Vogl.

Figure 3. Moritz von Schwind, Diana, Vienna Staatsoper.

1826: Oppositional Politics in Sehnsucht

For another case of concealed political content, let us consider a song from 1826, a year when censorship restrictions came to be tested and enforced in particularly infuriating ways. That spring, the great comic playwright and actor (also former opera singer and performer of Schubert part-songs) Johann Nestroy was jailed in Brno for the improvised lines he introduced in performance, following which the police canceled his contract and he relocated to Graz. It mattered not whether his extemporary jokes criticized heads of state or offended sexual mores or moral and religious norms: to depart from an approved script—to bring down the house without prior permission—was against the law.41 That year, too, the Parisian satirical weekly Le Figaro was founded: on its masthead appeared the words “Without the freedom to criticize, praise is empty” from Figaro’s soliloquy in Beaumarchais’s Le mariage de Figaro, the speech that had smashed through the barricades of Parisian censorship in 1784. The year 1826 also saw the formation of a secret society in Linz involving several of Schubert’s acquaintances. They called themselves Eos (Dawn) or the Frühaufstehgesellschaft—The Early-to-Rise Society—perhaps after the morning societies that formed in the early days of the French Revolution. The members were known as “Memnonites.” According to legend, a colossus associated with Memnon—son of Eos and Tithonus, he fell in battle defending Troy—gave out a lamenting cry at the hour of sunrise and then was mute for the rest of each day.42 The Memnonites had written an elaborate constitution and statutes and held assemblies in which democratic protocol could be practiced on mundane, seemingly apolitical subjects, preparing them for a post-uprising world. A branch organization was started in Vienna after two of its members, the brothers Franz and Fritz Hartmann, both students of law, moved there; they also attended Schubertiades at Spaun’s. The society’s statutes, membership, and its journal Morgenstern (later Lampe) have attracted renewed attention of late from scholars doubting that all this was simply harmless Biedermeier entertainment.43

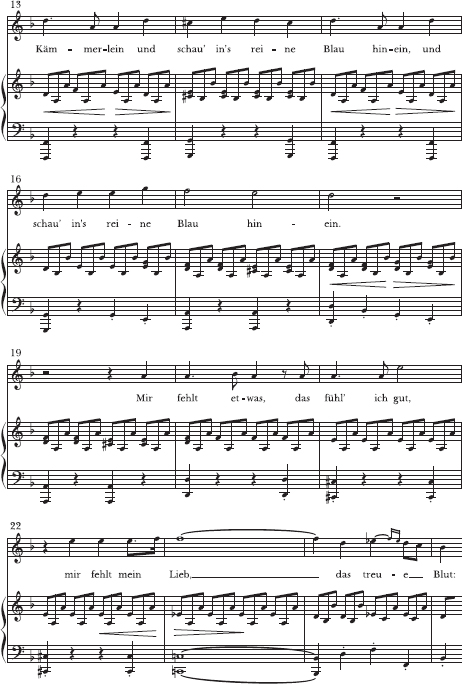

Nearly a decade after the Congress of Vienna, outrage over censored speech filled the air in that city. Now writers and artists could unite against this assault on their profession without needing to probe one another’s political persuasions because the most basic prerequisite for any form of representative government was open discussion. In 1826 there was no “foreign” tyrant to oppose; democratic-nationalist opposition was directed against Metternich’s Restoration government. This was the climate within which Schubert set the poem “Sehnsucht” by Johann Gabriel Seidl (1804–1875), a local Viennese poet who a dozen years later would himself take a position as a part-time censor. Schubert’s delightfully catchy song invites scrutiny because it is difficult to get the words of the poem to mean quite what the music’s character—its demeanor—and the rhetoric of its repetitions and phrase structure would imply; indeed, music plays an even greater role in shaping meaning here than in Der zürnenden Diana. Doubly alluring is that the poem also strikes an autobiographical pose; the fourth stanza depicts a poet struggling to overcome his writer’s block to compose this very song, Sehnsucht (D879):

Die Scheibe friert, der Wind ist rauh, |

The pane frosts over, the wind is raw, |

Der nächt’ge Himmel rein und blau: |

the nighttime sky so clear and blue. |

Ich sitz’ in meinem Kämmerlein, |

I sit in my little room |

Und schau’ ins reine Blau hinein! |

and gaze into pure blue! |

Mir fehlt etwas, das fühl’ ich gut, |

Something is lacking, this I well feel; |

Mir fehlt mein Lieb, das treue Blut: |

I miss my love, my true life’s blood, |

Und will ich in die Sterne seh’n, |

and when I gaze into the stars |

Muß stets das Aug’ mir übergeh’n! |

my eye must brim over with tears! |

Mein Lieb, wo weilst du nur so fern, |

My love, where do you tarry so far away, |

Mein schöner Stern, mein Augenstern?! |

my beautiful star, star of mine eye?! |

Du weißt, dich lieb’ und brauch’ ich ja,— |

You know ‘tis you I love and need,— |

Die Träne tritt mir wieder nah. |

Again my tears well up. |

I’ve tormented myself many a day, |

|

Weil mir kein Lied gelingen mag,— |

because no song will come together,— |

Weil’s nimmer sich erzwingen läßt |

for song never will be forced |

Und frei hinsäuselt wie der West! |

and murmurs forth freely like the west wind! |

Wie mild mich’s wieder g’rad’ durchglüht! — |

How the mild glow suffuses me again just now!— |

Sieh nur—das ist ja schon ein Lied! |

Ah, look—it is a song already! |

Wenn mich mein Loos vom Liebchen warf, |

If my lot has cast me from my love, |

Dann fühl’ ich, daß ich singen darf. |

then I feel that I may sing. |

Seidl’s poem is in five stanzas. The scene is a small chamber late at night. From here the poet gazes out into the nighttime sky; a rough wind frosts the windowpane. The first three stanzas concern a beloved absent star, addressed as “mein Lieb” in stanza three: “My love, where do you tarry so far away, My beautiful star, star of mine eye?!” (mein Augenstern). Stanza four shifts to unexpectedly inward expression, revealing a poet suffering from writer’s block: he has tormented himself for many a day but no song will come together because song will not be coerced but murmurs forth freely like the west wind: “Weil’s nimmer sich erzwingen läßt und frei hinsäuselt wie der West.” (To the west of Austria, we might reflect, lies France.) Suddenly the star’s rays create a warm glow—passing right through the frozen window—and look, already here is a song!

As soon as the poet’s muse appears his song comes together in a blink. Very charming. The next lines are puzzling, though. The final couplet is cast as a pithy summation whose “if-then” clause is meant to explain how the meditation on writer’s block follows from the yearning for the absent beloved. But something is amiss—why does no meaning spring into place? “If my lot has cast me from my love, then I feel that I may sing.” What does this intend? Why should the poet feel he can sing when his beloved is far away? We may be reminded of those famous lines from Pause in Die schöne Müllerin—“Ich kann nicht mehr singen, mein Herz ist zu voll” (I can sing no more, my heart is too full)—but that will not help us here because Seidl’s poem has nothing to do with unrequited love. What then? We step closer to understanding when we note that the words in the final verse are not “daß ich singen kann” (that I can sing) or “singen muss” (must sing) but “daß ich singen darf” (may sing). It is not that I am obliged to sing; rather, I am not barred from doing so. Moreover, “daß ich singen darf” makes a conceptual rhyme with the previous stanza’s “Weil’s nimmer sich erzwingen läßt / Und frei hinsaüselt wie der West!” The verbs “dürfen” and “erzwingen” ever so gently suggest a commanding presence, someone or something able to grant or force things. “Darf” and “warf” are not run-of-the-mill Lieder rhymes; “darf” plainly was chosen to sustain the murmur of protest in the previous lines.

Hearing the song in performance our attention may snag (mine does) on a disjunction between the meaning, on its face, of those words “Wenn mich mein Loos vom Liebchen warf, dann fühl’ ich, daß ich singen darf” (downcast at first, then cheery) and Schubert’s crystal-clear rhetoric, which turns to the major mode at the start of the strophe and builds to emphatic, almost triumphant, cadencing for the repeated pronouncement “daß ich singen darf, daß ich singen darf.” Nothing signals any ambivalence. Indeed, nothing suggests that these lines mean anything other than exactly what they say. By some mechanism, we must be able to hear what they say in a way that aligns with D-major song and dance, followed by the piano’s wistful commentary on it. Schubert’s setting makes us intuit a coherent meaning even if the words of the poem do not want to comply.

The song begins with a piano introduction in D minor with agitated triplets in the right hand against a bass descent through the chromatic tetrachord, D to A (see Example 3). In the triplets the alto voice descends in tenths against the bass, sandwiched between oscillating octave A♮s that seem locked in place. A memorable jolt in measure 3 disturbs the flow as the alto, having failed to move when the bass fell to C♮, sinks to D♯ against the bass B♮; it takes six beats before the chromatic descent can resume and move to a D-minor cadence. With the singer’s entry the bass descent begins anew, passing over the C♮ that had threatened to inflect B♮ as a dominant in measure 3. When the pattern starts up again for strophe two (“Mir fehlt etwas”), the bass stalls almost immediately on C♯ for two bars while the vocal melody is jerked up a fifth before pushing a half step higher to F♮ on the word “Lieb” just as the bass and alto sink to octave C♮s and E♭ respectively. The resulting unstable dominant seventh echoes the disturbance in the piano introduction and “Lieb” is held out for five full beats before tension is released in two quick cadences to B♭ in the middle of the verse (B♮ is bypassed this time). This places an abrupt, utterly unexpected emphasis on the word. From this point forward the D-minor “lamento” pattern loses its grip on the remaining strophes—but note that it is a bass C♮ in measure 45 (not shown in the example) that turns the harmony to a sad A minor for the cadence-ending strophe three at “Die Thräne tritt mir wieder nah.” Tears—a lament—step nearer again.

Example 3. Sehnsucht, D879, mm. 1–25.

Though the harmonic trajectory of each strophe is different, Schubert returns to the tonic for each new beginning—to D minor for strophes one, two, and four; D major for the apostrophe to the beloved star in three, and again when the star’s glow touches the poet in strophe five. The first three strophes elide one into the next and the later ones close firmly. This is underscored by the words in the last line of each, which are always heard twice, followed by an echo of the formulaic cadence in the piano. The only exception to this pattern is in strophe three where the words “dich lieb’ und brauch’ ich ja” repeat instead. A casual translation of this line, “you know that I love and need you,” would miss a crucial point expressed in the poet’s word order: by placing dich at the head of the clause, ich at the end, a special emphasis is created: “You know ‘tis you I love and need.” Seidl’s positioning of the deictic pronoun dich lays stress on the identity of the beloved, and Schubert has us linger over these words.

In the poem’s cryptic final couplet the formulation “Wenn mich mein Loos vom Liebchen warf” is awkward, undoubtedly because the poet was constrained by the need for a rhyme with “singen darf.” Words declaimed in song will sometimes rearrange themselves in our heads when musical forces gain the upper hand. To make a better fit with Schubert’s buoyant, upbeat music my own mind strains to assemble a meaning to this effect: If my lot’s been thrown to me by my love (“Wenn mir mein Loos das Liebchen warf “) then I feel that I may sing. His “Liebchen” grants him permission to sing, in conformance, say, with the courtly love tradition whereby a lowborn singer takes commands from his lady. But the syntax won’t allow this—“mich” is the accusative reflexive pronoun, not the dative “mir.”

All these problems fall away if we take into account something external to the text. The song dates from the spring of 1826 and the poem was published that same year, just as tensions were mounting in Vienna.44 The three words on which this politicized hearing turns (less so a song about absent love, which can run parallel to it until the trouble at the end) are “Lieb,” so drastically underscored by Schubert; “darf “; and most inconspicuous of all, “fühl.” Moreover, Schubert’s setting does indeed perfectly take the last line at face value, only with a different mien than we may have first thought.

“Words are proscribed,” Franz Grillparzer would observe in an April 1826 conversation with Beethoven, “it’s a good thing that tones, the exponential representatives of words, still are free.” This remark was entered into Beethoven’s conversation book just a few days after the raid on the literary association and social club known as the Ludlamshöhle (which took place during the night of 18 April and continued into the wee hours of the next morning).45 Grillparzer, who was placed under house arrest, and Seidl were both members; Schubert and Eduard von Bauernfeld (1802–1890), author of the libretto for Schubert’s Der Graf von Gleichen (it would be banned in October) and a passionate advocate of free speech, were on the verge of joining. By chance, the whole affair landed on Bauernfeld’s desk (he was an intern—Konzepts-Praktikant—in the department of the Lower Austrian Government that was expected to ratify such charges) and he was able to sweep it under a busy rug: “Had the police delayed their interventions by but a single day Schubert and I would also have become ‘Ludlamites’ and I might have had to assist at my own enquiry. What irony!”46 Even before this incident, however, there was talk that the censors did not have control over music. The political meaning in Sehnsucht comes together by a counterintuitive accent and the realization that “Lieb” or “Liebchen” names the ideal: “Wenn mich mein Loos vom Liebchen warf, / Dann fühl’ ich, daß ich singen darf” (If it is my lot to be cast away from my beloved Liberty then I truly feel that I may sing, that I may sing). The piano, all alone at the final cadence, has the last word: “singen.” I may sing—but not declare my love openly. Perhaps it was here that the political and the personal merged (Example 4).

Tucked away in the new Schubert edition’s typescript critical report for volume 5 of Lieder (1985) is mention of an intriguing autograph leaf in Seidl’s Nachlass in which the poem appears outfitted with an alternate final couplet: “Muß ich, mein Lieb, dir ferne seyn, / Gleich stellt das Lied von selbst sich ein!” This is no less ambiguous. The antecedent clause is clear as “If I must be distant from you, my love,” but the consequent “sich einstellen” can suggest numerous possibilities. Are we to understand “Then, promptly, the song does (my) duty all by itself “? If so: in love or in war? Or perhaps we hear “stellt … sich ein” as a form of “zusammenstellen” (to put together), allowing the meaning “Suddenly the song comes together all by itself “? Too many mixed signals fly for any one meaning, or even a pun, to spring into place.

Further small variants in the manuscript poem let us conclude that this was likely the earlier draft (see Figure 4). The second stanza’s first line reads “Mir fehlt etwas, das merk ich gut.” Beneath merk (to notice) we can just make out an erased fühl (to feel), the word that appears both in Schubert’s song and in Seidl’s 1826 publication, but this substitution was plainly made because fühl recurred in the last lines of the same stanza, “Und will ich in die Sterne seh’n, / Fühl ich die Augen übergeh’n” (When I wish to gaze into the stars, I feel my eyes brim over), a routine formulation next to the publication’s “muß stets das Aug’ mir übergeh’n” (again and again my eye must brim over). The excision of fühl at this point frees up this word for “Dann fühl ich, daß ich singen darf.” The only other variants are minor (but telling) ones. The penultimate stanza ends “Weil nimmer sich erzwingen lässt / Weil’s frei hinsäuselt wie der West” (in place of “Weil’s nimmer sich erzwingen lässt / Und frei hinsäuselt wie der West” in the publication). In the manuscript poem, interestingly, the first of these two clauses floats free of any referent; for a brief instant we do not know what will not be forced.

Example 4. Sehnsucht, D879, mm. 73–89.

Although the sense of the closing couplet in the manuscript poem is just as indeterminate as in the publication, its rhythm, sounds, and rhyme make better poetry than “Wenn mich mein Loos vom Liebchen warf.” A political meaning is not impossible but it is more remote. How, when, or from whom the suggestion came to replace the final couplet we do not know. Only one thing is sure: the manuscript version cannot be sung to Schubert’s music. His entire song is calibrated to be able to proclaim at the end: “daß ich singen darf.”

Sehnsucht is only one song among many (Der zürnenden Diana is another) that must have delighted attentive listeners who recognized Schubert’s virtuoso command of music’s power to shape verbal meaning. In Sehnsucht the pleasing surface and understated rhetoric create emphases similar to the subtle verbal stresses that skilled actors like Nestroy employed on the stage to get around what censorship forbade.

Figure 4. Johann Gabriel Seidl, Sehnsucht, autograph ms., Wienbibliothek.

1. Beethoven’s own Fidelio is a case in point. Even at the 1805 premiere the French libretto’s revolutionary-era story was displaced to sixteenth-century Seville to escape Viennese censorship (in contrast to adaptations of this story for other European stages). For the 1814 revival strategic revisions to the libretto and music made the story current, yet the freedom that Beethoven’s Fidelio held out remained but a fervent hope and the historical mask was not lifted.

2. August von Kotzebue, Ode an Napoleon (Moscow, 1813), 12. My translation. “Mögen Tausende zu Grunde gehen, hingewürgt von Hunger, Pest und Schwert; Wenn nur siegreich Deine Fahnen wehen, und Dich nichts in Deinen Planen stört. Nenne dich die Welt entmenschter Tyger! Treu und Glauben schändender Betrüger! Immerhin, bist Du allein doch Sieger! Dieser Zweck ist jedes Mittel werth.” One revision Georg Friedrich Treitschke made to Beethoven’s Fidelio in 1814 was to add a dramatic recitative for Leonore (adapted from Ferdinando Paer’s Leonora), “Abscheulicher! Wo eilst du hin?” In it, she excoriates the tyrant who no long feels pity, no longer hears humanity’s voice, has but a “Tigersinn” (the mind of a tiger). The vast majority of publications listed in Ernst Weber’s Lyrik der Befreiungskriege (1812–1815): Gesellschaftspolitische Meinungs- und Willensbildung durch Literatur (Stuttgart, 1991), 336–59, are poems and songs celebrating German emancipation and war heroes, but Weber also turned up two volumes apparently in praise of Napoleon “from one of his most avid followers and admirers” in Königsberg, ca. 1813–14 (343), and the above-mentioned ode attributed to Kotzebue (341).

3. A fuller biographical sketch of Körner may be found in Susan Youens, Schubert’s Poets and the Making of Lieder (Cambridge, 1996), 51–150. Besides Schubert’s settings of Körner she discusses settings by north German composers. Details about Körner’s competing offers from Pállfy and Lobkowitz and his activity as a court poet are included in the narrative biography by Heribert Rau, Theodor Körner: Vaterländischer Roman in zwei Theilen (Leipzig, 1863).

4. Jonathan Sperber, “The Atlantic Revolutions in the German Lands, 1776–1849,” in The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History, ed. Helmut Walser Smith (Oxford, 2011), 144–168, esp. 158. The picture he sketches is broad but Sperber believes that the early German nationalists were not concerned, as were their Atlantic revolutionary counterparts, with “the creation of a nation of equal citizens, repudiating the distinctions of the old regime society of orders” (157). Theirs was less a class struggle than an effort to forge a national identity, to which end they employed a range of scientific evidence, linguistic theories, and philosophical arguments.

5. Heinrich Heine, Ludwig Börne: A Memorial, translated with excellent commentary and an introduction by Jeffrey L. Sammons (Rochester, NY, 2006), xi.

6. The poet Wilhelm Müller fought in the war against Napoleon as well as in the Greek war of independence. In 1822 the journal Urania (the1823 issue contained the first twelve poems of his Winterreise) was given the Viennese censor’s damnatur, hence it was not for sale in Austria. Susan Youens, Retracing a Winter’s Journey: Schubert’s “Winterreise” (Ithaca, NY, 1991), 10. Schubert originally set only these twelve poems. He kept intact their order in Urania even after composing part two of Winterreise (in the month following the poet’s death) from the new poems Müller had interleaved before reissuing his poetic cycle.

7. Hans Sturmberger reports that as punishment for his free-thinking ideas C. E. Bauernschmied was appointed censor in Linz. The influence of Bavarian constitutionalism—Bavaria was under French stewardship—was even more pronounced there than in Vienna. Sturmberger, Der Weg zum Verfassungsstaat: Die politische Entwicklung in Oberösterreich von 1791–1861 (Vienna, 1962), 29. Contemporary reports abound of Metternich’s efforts to enlist dissident liberals as censors: Joseph Schreyvogel succumbed in 1817; Charles Sealsfield resisted. In Johann Nestroy’s 1848 play Freiheit in Krähwinkel the liberal Ultra replies to just such an offer from the Burgomeister with a brilliant tirade against censorship. Censorship restrictions finally were lifted in March 1848, only to be reinstated by year’s end. Following the premiere in Vienna on July 1, Freiheit in Krähwinkel played nightly to a packed house until the end of the season. Johann Nestroy, Stücke 26.1, Historisch-kritische Ausgabe, ed. John R. P. McKenzie (Vienna, 1995), 1–2.

8. James J. Sheehan, German History 1770–1866, The Oxford History of Modern Europe, ed. Lord Bullock and Sir William Deakin (Oxford, 1989), 423–24.

9. Moriz Enzinger, “Zur Biographie des Tiroler Dichters Joh. Chrys. Senn,” Archiv für das Studium der Neueren Sprachen 156 (1929): 169–83; letter of 24 February 1823 (176).

10. Werner Ogris, “Die Zensur in der Ära Metternich,” in Humaniora Medizin—Recht—Geschichte: Festschrift für Adolf Laufs zum 70. Geburtstag (Berlin, 2006), 248. Gentz had already backed away from his early support of the French Revolution after reading and translating Edmund Burke’s pamphlet Reflections on the Revolution in France ca. 1793.

11. Senn’s story has often been told and Schubert’s two songs on poems of Senn, Selige Welt (D743) and Schwanengesang (D744), have been richly explored in recent years. Suzannah Clark’s analysis of the “transformational” voice leading in Selige Welt, for example, is in dialogue with Gottfried Wilhelm Fink’s (we believe) observations on harmony and Charles Rosen’s comments on rhythm, phrase structure, and the song’s political implication. See Clark, Analyzing Schubert (Cambridge, 2011), 67–73. Fink’s remarks appeared anonymously in the 24 June 1824 issue of the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung; Rosen’s in “Schubert’s Inflections of Classical Form,” in The Cambridge Companion to Schubert, ed. Christopher H. Gibbs (Cambridge, 1997), 77–78. Susan Youens explores how Schubert revisited Schwanengesang in another A-flat minor-major piece belonging to the same genre in “Swan Songs: Schubert’s ‘Auf dem Wasser zu singen,’” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 5/2 (2008): 19–42. Philosophical (Hegelian) and political meanings in the Senn songs are taken up by Werner Aderhold in “Johann Chrisostomus Senn,” in Schuberts Lieder nach Gedichten aus seinem literarischen Freundeskreis: Auf der Suche nach dem Ton der Dichtung in der Musik. Kongreßbericht Ettlingen 1997, ed. Walther Dürr, Karlsruher Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft, vol. 1 (Frankfurt am Main, 1999), 97–111. Aderhold also contributed entries on these songs to the Schubert Liedlexikon, ed. Walther Dürr, Michael Kube, Uwe Schweikert, and Stephanie Steiner, in collaboration with Michael Kohlhäufl (Kassel, 2012), 591–92.

12. Christian Jansen, “The Formation of German Nationalism, 1740–1850,” in The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History, ed. Helmut Walser Smith (Oxford, 2011), 234–59, 243.

13. Ibid., 244–48. Jansen carefully notes regional differences (Bavarian, Prussian) in the accelerating development of organized nationalism. To indicate the range of early German nationalisms he provides sketches of the thinking of five influential representatives: Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, the founder of gymnastic (paramilitary) societies with nationalist aspirations, and Ernst Moritz Arndt, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Daniel Schleiermacher, and Heinrich Luden, 245ff.

14. Sturmberger reports this in Der Weg zum Verfassungsstaat 27, citing G. Grüll, Die Robot in Oberösterreich (1952), 216ff.

15. Michael Kohlhäufl, Poetisches Vaterland: Dichtung und politisches Denken im Freundeskreis Franz Schuberts (Kassel, 1999), 260. Kohlhäufl’s book sheds much light on political imagery in the poems that Schubert chose to set; he leaves others to explore how Schubert’s music inflects those meanings.

16. I have discussed several such censorship incidents in the opening chapters of my book Vanishing Sensibilities: Schubert, Beethoven, Schumann (New York, 2012).

17. Six hundred thousand soldiers fought for three days in this bloody battle known as the Völkerschlacht before Napoleon’s French army, supplemented by Italian, Polish, and German troops from the Confederation of the Rhine, lost to the coalition of Russians, Prussians, Austrians, and Swedes.

18. Ludwig Börne: A Memorial, 75–76. My brief quotations are all from Sammons’s translation. “Alt Deutsch” refers to the propensity of the early nationalist groups to trace their tribal roots back to the Middle Ages.

19. Ibid., 89. These remarks take aim at the conservative critic Wolfgang Menzel, who, to Heine’s witty and earnest relief, “joyfully vaulted back into the old circle of ideas … after the air grew cooler.”

20. Heinrich Heine, Ludwig Börne: Eine Denkschrift und kleinere politische Schriften, ed. Helmut Koopman, vol. 11 of Historisch-kritische Gesamtausgabe der Werke, ed. Manfred Windfuhr (Hamburg, 1978), 83–84, 97–98. Heine writes Teutschthümler when he speaks of Menzel (see 84 and 97), mimicking one such mannerism. For more examples see vol. 11’s massive critical commentary. Members of a Burschenschaft in Linz also had distinctive paraphernalia, carrying gnarled walking sticks with friends’ names carved into them or wearing unmarked white caps. Sturmberger, Der Weg zum Verfassungsstaat, 22.

21. Heinrich Heine, Briefe aus Berlin, ed. Jost Hermand, vol. 6 of Windfuhr, Historisch-kritische Gesamtausgabe der Werke, 43, 367. See also “The Formation of German Nationalism, 1740–1850,” 247. Heine’s readiness to name the names of political (nationalist) activists so soon after the Carlsbad Decrees was noted with surprise in the contemporary press.

22. French Affairs: Letters from Paris, vol. 7, bk. 1 of The Works of Heinrich Heine, trans. Charles Godfrey Leland (Hans Breitmann) (London, 1893), 14.

23. There is just one more Körner song from 1818. Ilija Dürhammer, “Deutsch- und Griechentum. Johann Mayrhofer und Theodor Körner,” in Schubert 200 Jahre, Schloß Achberg: Ich lebe und componiere wie ein Gott,” ed. Ilija Dürhammer and Till Gerrit Waidelich (Heidelberg, 1997), 21–24.

24. Ruth Melkis-Bihler, “Politische Aspekte der Schubertzeit,” in Schuberts Lieder nach Gedichten aus seinem literarischen Freundeskreis, 1–96, quote at 92. Her information on Senn’s and Mayrhofer’s fraternity membership is drawn from Max Doblinger and Georg Schmidgall, Geschichte und Mitgliederverzeichnisse burschenschaftlicher Verbindungen in Alt-Österreich und Tübingen 1816–1936, with an introduction by Paul Wentzke, Burschenschafterlisten, vol. 1, ed. Paul Wentzke (Görlitz, 1940), 15. The full list of twelve is Franz v. Bruchmann; Graf Colloredo (formerly a “Prager Teutone”); Anton, Freiherr von Doblhoff-Dier; Alois Fischer; “Gerhardi … aus Göttingen”; Karl Hieber; Karl Kiesewetter; Johann Mayrhofer; Josef von Scheiger; Georg Schuster; Johann Senn (later a member of Libera Germania Innsbruck); Karl Stegmayer. Doblinger and Schmidgall report that the police broke up the group even before it could be formally constituted as a Burschenschaft but that its members had already undertaken outings called “Turnfahrten” (14). Senn was arrested following a party for Alois Fischer that Bruchmann and Schubert also attended on 20 January 1820. Gerhardi fled to Prague and shot himself before the police could catch up with him. See also Enzinger, “Zur Biographie des Tiroler Dichters Joh. Chrys. Senn,” 172.

25. Goethe’s poem about a furtive passionate liaison first appeared in the early 1770s. It was revised and republished in 1789 and reissued again in 1810 under the now familiar title “Willkommen und Abschied”—perhaps its imagery sounded differently in later political climates.

26. Theodor Körner, Leyer und Schwert, 3rd ed. (Berlin, 1815), 74ff.

27. Youens, Schubert’s Poets and the Making of Lieder, 130.

28. Ibid., 154, citing Carl Glossy, “Aus den Lebenserinnerungen des Freiherrn von Spaun,” in Jahrbuch der Grillparzer-Gesellschaft, 8 (Vienna, 1898), 275–303, quote at 295.

29. Otto Erich Deutsch, Schubert: Memoirs by His Friends, trans. Rosamond Ley and John Nowell (London, 1958), 14.

30. Ovid, Metamorphoses, books 1–8, trans. Frank Justus Miller, revised by G. P. Goold, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA, 1994), 135–39.

31. For more on discussions at the Congress of Vienna on the repatriation of artworks, see Bette W. Oliver, From Royal to National: The Louvre Museum and the Bibliothèque Nationale (Plymouth, UK, 2007), 65ff. The dispersal of the Orléans collection is discussed in Francis Haskell, The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition (New Haven, 2000), 22–29; and Nicholas Penny, The Sixteenth-Century Italian Paintings, vol. 2: Venice, 1540–1600, National Gallery Catalogues (New Haven and London, 2008), 461–70.

32. Michael Thimann comes to this conclusion in his study of Parmigianino’s Actaeon frescos in Fontanellato where Latin didactic inscriptions frame the pictures on the ceiling of the Rocca Sanvitale. Michael Thimann, Lügenhafte Bilder: Ovids “favole” und das Historienbild in der italienischen Renaissance (Göttingen, 2002), 145, passim. I give thanks to Katelijne Schiltz for directing me to this stimulating study. The masculine Diana in the Orléans Mort d’Acteon is an intriguing obverse of Parmigianino’s remarkably feminine Actaeon.

33. Gedichte von Johann Mayrhofer (Vienna, 1824). Schubert’s text diverges from Mayrhofer’s publication in minor details: Mayrhofer’s published poem has “im zornigen Erröthen” and “am buschigen Gestade” whereas Schubert’s song text reads “im zürnenden Erröthen” and” “am blühenden Gestade.” Neither change is important for the present discussion. In addition, the first edition of the song is titled Die zürnende Diana, as it was in Schubert’s composition manuscript, in which it was later corrected to Der zürnenden Diana.