14. THE COMPOSER

Besides, Mr. B was close to Tschaikovsky, and had, he explained to us, frequent consultations with him, including, apparently, the occasional phone call, and the composer often “helped”—and, with curious frequency, approved!

Bernard Taper, Balanchine’s first biographer, reports an exchange that illustrates Balanchine’s effortless rapport with Tschaikovsky. After deciding on the metronome tempo of sixty-nine for a recording being made of Serenade’s final movement, Balanchine asked our superb conductor, Robert Irving, “What does Tschaikovsky say?” After checking the composer’s arrangement, Irving reported, “Ninety-six.” “It must be a misprint,” Balanchine replied—and decided on sixty-six, even slower.

Tschaikovsky’s death, just over ten years prior to Balanchine’s birth, provided little impediment—and perhaps considerable assistance—to their bond: they were St. Petersburgers! “Petersburg is a European city that arose in Russia by miracle,” Balanchine explained, and “I was born in the Petersburg that Tchaikovsky had walked in.” Tschaikovsky, he said, was a “Russian European.” Like Balanchine.

So great was Balanchine’s reverence for his compatriot that he agreed to meet, in the final months of his life, over thirty times with the Russian writer and musicologist Solomon Volkov to speak (in Russian) about Tschaikovsky. At a time when most of us will talk of ourselves, setting the record or setting it straight, Balanchine wanted to talk about Tschaikovsky. He loved him, really loved him—the music and the man.

“I don’t quite understand how they examine the life and the works separately,” Balanchine told Volkov. The result is a telling twinning: Balanchine’s life and work filtered through Tschaikovsky’s life and work. “Tchaikovsky is Pushkin in music,” said Balanchine, “supreme craftsmanship, exact proportions, majesty.” One can, I believe, with neither exaggeration nor melodrama, conclude, by evidence of Serenade alone, that these two “Russian Europeans” indeed have a truly mystical bond—of country, culture, soul, and sound—that was sealed onstage, night after night, in Balanchine’s theater.

Pyotr Illyich Tschaikovsky is the musical father of classical ballet. “Tchaikovsky was convinced from the days of his youth,” said Balanchine in 1982, “that ballet was an art, equal to the other arts and this was a hundred years ago! Most people are only coming to that viewpoint now.” As composer of three of the four cornerstone ballets of the classical canon—Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker (the fourth is Giselle, composed by Adolphe Adam in 1841)—Tschaikovsky reigns supreme. “The stage, with all its tinsel,” the composer wrote of his love of composing music for the ballet, “continues to attract me.” His music raised the standards in the last decades of the nineteenth century, from the rather rinky-dink tunes with perfunctory, predictable rhythms that often characterized “ballet music” to that of symphonic music, with orchestral scores that stand alone in concert yet still brim with drama, romance, emotion, and pathos. And such splitting sweetness. His music is the colossus, upon which the art of ballet stands. “If it were not for Tchaikovsky,” Balanchine stated unequivocally, “there wouldn’t be any dancing.”

In Balanchine’s aqua analogy, where dancers are like fish, Tschaikovsky—his name synonymous with his music—provides our most essential, most eminent aquarium, a liquid land of misty opulence.

And such melodies!

Ballet doesn’t exist without music. It has been tried, naturally, but is a dead event. We cannot move without music; it is our animator, our propulsion, our raison d’être. “I couldn’t move without a reason, and the reason is music,” Balanchine said. He considered the music first and his choreography second in importance—thus his insistence on a first-rate, live orchestra. He liked to say that it was fine to close your eyes at a ballet performance and just listen. And to our frequent, only slightly amused lament, unlike in most dance companies, Mr. B told us to keep pace to the conductor’s tempos and not the reverse. We followed the music; the music did not follow us.

Balanchine’s catalogue lists a total of twenty-six works choreographed to Tschaikovsky, spanning five decades of allegiance, with fifteen of them extant. Balanchine’s musical compass was entire, and he was no snob despite being a trained classical musician; though he did stop short at pop music, admitting, “I can’t understand rock ’n’ roll.” He choreographed dances to music from over fifty composers, from classical to jazz to Hollywood and Broadway show tunes. He made dances to Bach, Mozart, Stravinsky, Bizet, Schumann, Handel, Brahms, and Schubert; to Verdi, Puccini, and Wagner; to Hindemith, Chabrier, Ravel, Rossini, Rachmaninoff, Offenbach, Chopin, Saint-Saëns, and Rimsky-Korsakov; to Grieg, Rieti, Donizetti, Mussorgsky, Gounod, and both Strausses (Johann and Richard); to Liszt, Delibes, Borodin, Glazunov, Minkus, and Franz Léhar; to Kurt Weill, John Philip Sousa, Charles Ives, George Gershwin, and Irving Berlin; to Vernon Duke, Richard Rodgers, Frederick Loewe, Harold Arlen, Paul Bowles, and Johnny Mercer.

But again and again he returned home, to Tschaikovsky, the Russian composer of his boyhood debut in The Sleeping Beauty. And at the end of his life, at age seventy-seven, he came back, yet one last time, to Tschaikovsky, in his transcendent masterpiece Mozartiana, which he positioned—no, he did not say this, but how clear it is!—in heaven, a joyous place filled with wit, elegance, and explicit prayer, with dancers dressed in black, trimmed in white lace. So Balanchine closed his travels with Tschaikovsky in a perfect circle: this 1981 version of Mozartiana was an entirely new ballet to the same music that had marked his first full ballet to Tschaikovsky, in 1933, at age twenty-nine.[*3] But in his final version, Balanchine, rascal to the end, changed, as he did with Serenade, the order of the composer’s score.

Serenade thus became Balanchine’s second complete ballet to the composer’s work, and it is interesting to note that in both of these scores Tschaikovsky paid homage to his musical god: “I not only love Mozart, I worship him.” I view Serenade as Balanchine’s communion with Tschaikovsky, a spiritual union that endured, fully alive, for the remaining fifty years of Balanchine’s life. The last festival he conceived, in 1981, two years before he died, when he was already in declining health, was to celebrate Tschaikovsky; it featured over twenty works by the composer. Alas, Tschaikovsky never knew, never saw, the beauty Balanchine shaped to his work, or the incalcuable effect that these ballets have had in bringing his music to a whole new audience in their visualizations—nor did he hear the changes his compatriot made in his music!

I, too, love Tschaikovsky. For most dancers, his music is the pervasive aural aura of our earliest years at the barre, in class variations, in teenage school performances. And, for me, it became the physically inculcated soundtrack of my young life when, starting at age eleven, I danced, year after year, in The Nutcracker. (I did know who the Beatles were and had heard of the Rolling Stones and of someone who growled unintelligibly called Bob Dylan and another who groaned unintelligibly called Leonard Cohen—but they were all of less than little interest.) Here lies a great obstacle for me: using words on a page to convey the experience of Serenade. The music, the music, the music. While I certainly can accurately describe these thirty-three minutes of celestial sound as lyrical, melancholy, delicate, anguished, sacral, otherworldly, exalted, vivacious, joyous, and elegiac, this will transmit to you little actual feeling. What I cannot convey is the effect of these sounds, rhythms, moods, or swaying melodies. Music enters the mind instantly like no other medium, and, if a connection is made in the core, can pierce the heart. It carves out a different route than language, blessedly bypassing intellect. “Tenderness” is perhaps the single word—should I have to choose one—to describe Tschaikovsky’s Serenade, tenderness punctuated by sorrow. The sorrow. The rapture and the loss, inseparable. And the violins—ah, the violins!

Unlike Balanchine, who left us only his ballets as his autobiography, Tschaikovsky was quite the correspondent and wrote not only voluminously—over five thousand letters to almost four hundred recipients—but eloquently, intimately, often with brutal honesty.

How beautifully Tschaikovsky breaks—as does Balanchine—the much-adored romanticization of the great artist with a raging ego and selfish temperament. His letters demonstrate compassion and kindness, generosity, penetrating self-knowledge, warmth, frequent gratitude, and a moving humility. He called himself on one occasion “merely a talented person, but no extraordinary phenomenon.” But he also revealed his irritability, shyness, reclusiveness, sensitivity, and moody, highly emotional states; he wept easily, frequently. He offers numerous damning judgments: he detested Brahms—“What a giftless bastard!”—calling him “a pot-bellied boozer” and “a conceited mediocrity”—all the while also enjoying the occasional inebriated socializing with him. And he wrote much about the day in, day out relentless struggle, particularly as his celebrity grew, to obtain the right conditions, to be alone, to work.

“I love fame and strive for it with all my soul,” he wrote the year he composed Serenade. “But from this, though, it does not follow that I love the manifestations of fame that take the form of banquets, suppers, and musical soirées, at which I have indeed suffered, just as I always suffer in the company of people who are alien to me…I want, desire, and love people to take an interest in my music and to praise and love it, but I have never sought to get them to take an interest in me personally, in the way I look or in what I say.”

His description of the delicate, thrilling process he calls “inspiration” is unmatched in its clarity:

The SEED of a future composition usually reveals itself suddenly, in the most unexpected fashion. If the soil is favourable…this seed takes root with inconceivable strength and speed, bursts through the soil, puts out roots, leaves, twigs and finally flowers. I cannot define the creative process except through this metaphor…All the rest happens of its own accord. It would be futile for me to try and express to you in words the boundless bliss of that feeling that envelops me when the main idea has appeared…I forget everything, I am almost insane, everything inside me trembles and writhes…one idea presses upon another. Sometimes in the middle of this enchanted process some jolt from outside suddenly wakens you from this somnambulist state…and reminds you that you have to go about your business. These breaks are painful, inexpressibly painful…But there is no other way. If that state of the artist’s soul…were to continue unbroken, it would not be possible to survive a single day; the strings would snap and the instrument would shatter to smithereens. Only one thing is necessary: that the main idea…appear not through SEARCHING but of its own accord as the result of that supernatural, incomprehensible force which no one has explained, and which is called INSPIRATION…I consider it is the duty of the artist never to give way, for LAZINESS is a very powerful human trait. For an artist there is nothing worse…Inspiration is a guest who does not like visiting those who are lazy. She reveals herself to those who invite her. YOU MUST, YOU HAVE TO OVERCOME YOURSELF.

Such eloquence throws into stark relief the virtually total lack of writing of any kind left to us by Balanchine, who said, “I am silence.” He left no diaries, no memoirs, a bare handful of short notes—a rarity among artists of all disciplines. Truly he was a cloud passing over and wanted it so.

Pyotr Illyich Tschaikovsky’s life was defined by his relationships with three women: his mother, his wife, and his patron. Born in 1840 in Votkinsk, a small town about nine hundred miles southeast of St. Petersburg, Tschaikovsky was the second son of a family with six children and many generations of men dedicated to military and government service. His Ukrainian Cossack great-grandfather served under Peter the Great. And the civil service was to be young Pyotr’s destiny—as it was to be Georgi’s. Tschaikovsky’s mother, eighteen years her husband’s junior, was, also like Balanchine’s, his father’s second, much younger, wife.

At age ten, the boy was abruptly separated from his family, when he was shipped off (again, like young Balanchivadze) to board at the prestigious Imperial School for Jurisprudence in St. Petersburg, to train as an imperial administrator. Four years later his mother’s sudden death from cholera began his lifelong mourning.

“Tchaikovsky loved his mother more than his father,” Balanchine told Volkov. “Even when he was a grown man he couldn’t talk about her without tears…It was an open wound for the rest of his life…Childhood impressions are…always the most powerful. This holds particularly for musicians and dancers because they usually start studying music and ballet at a very early age.”

While the young Tschaikovsky had been an outstanding student—in addition to Russian, he spoke Italian, French, English, and German—he also excelled at piano and composition. After completing his course at the School of Jurisprudence, he decided, at age twenty-two, to devote himself to music, and his talent, soon recognized, resulted in a teaching position at the newly established Moscow Conservatory. By his midthirties he had already become a well-recognized composer of singular, occasionally controversial, accomplishment. When he composed Serenade, in 1880, he was just forty years old, but the preceding few years had been the worst of his life—defining years, precipitated by his marriage.

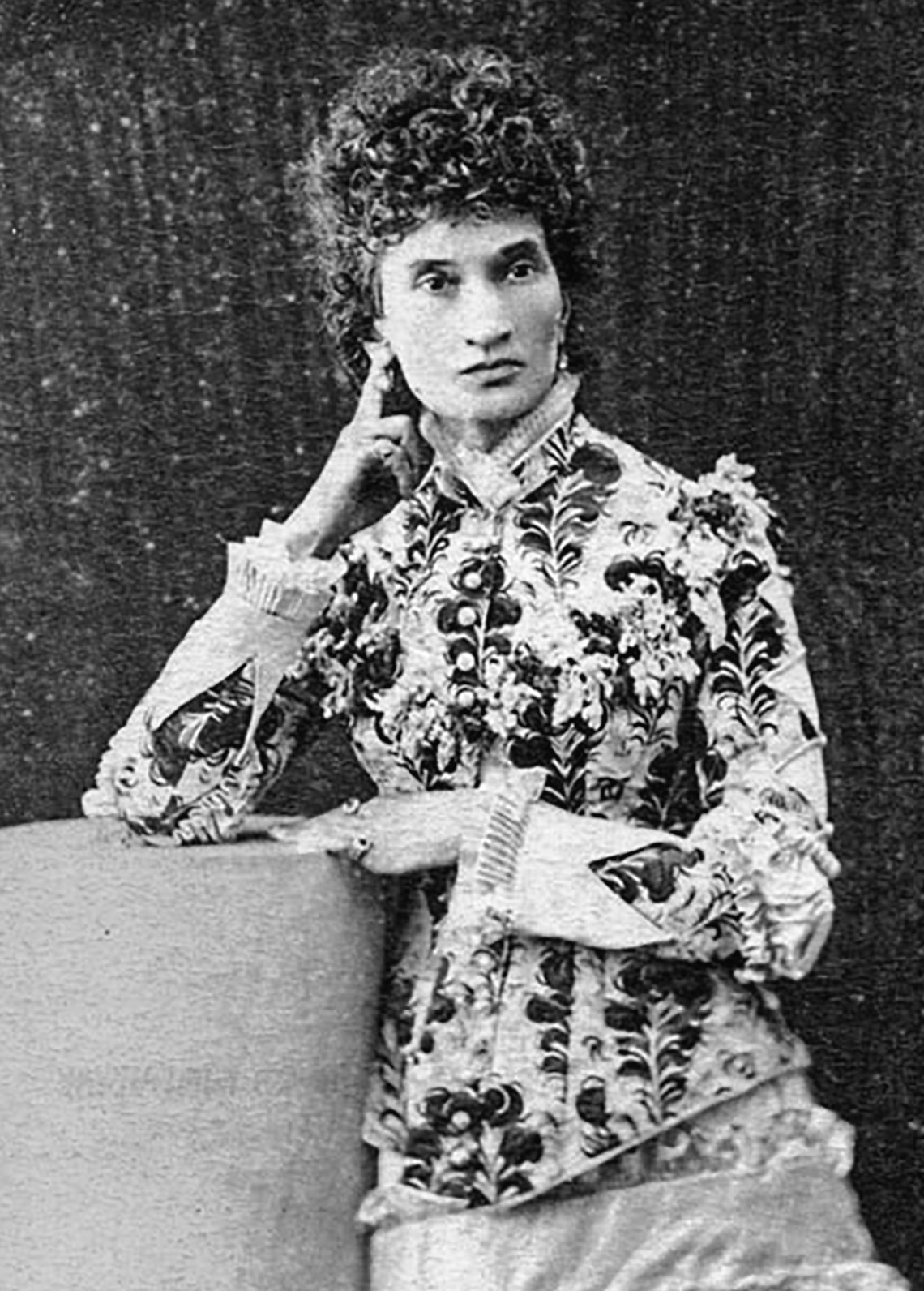

Pyotr Illyich Tschaikovsky, 1867 (ullstein bild Dtl./Getty Images)

Tschaikovsky was homosexual at a time in Russia when it was very dangerous and illegal, and the attendant shame and secrecy were particularly threatening to one of budding fame and ambition, so he decided at age thirty-six that he must abandon “forever my habits.” (He never did.) He wrote to Modest, one of his brothers, who was also homosexual: “I find that our inclinations are for both of us the greatest and most insurmountable obstacle to happiness, and we must fight our nature with all our strength.”

Fate soon provided. In May 1877, the composer received several unsolicited, passionate letters from a twenty-eight-year-old woman, Antonina Ivanovna Miliukova, who had briefly attended the Moscow Conservatory. She had been secretly in love with Tschaikovsky for four years, since a chance meeting that he did not recall.

“I am dying of longing,” she wrote to the composer. “My first kiss will be given to you and to no one else in the world…I cannot live without you, and so maybe soon I shall kill myself. So let me see you and kiss you so that I may remember that kiss in the other world.” Thus began the disaster.

“I have decided to marry,” wrote Tschaikovsky to Modest. “It’s unavoidable. I have to do this, and not only for myself, but also for you…for everyone I love. Especially for you!…Homosexuality and pedagogy cannot get along together.”

Miliukova and Tschaikovsky had met for the first time at his instigation on June 1, and three days later he proposed, telling her what she could expect from him “and on what she should not count,” namely he offered her “brotherly” love. He told her that he required complete “freedom,” though it is quite possible, given the times, that his bride-to-be still did not comprehend that he was homosexual—or perhaps she did not regard this as a hindrance.

“Why did I do this?” he wrote three days before the wedding. “Some force of Fate was driving me to this girl…I told my future wife that I did not love her…It is very distressing, through force of circumstances, to be drawn into the position of a bridegroom who, moreover, is not in the least attracted to his bride.” But Tschaikovsky was, of course, inherently romantic—not about conjugal bliss but about “Fate” as a living force.

At the altar—one of the two witnesses was Tschaikovsky’s most recent young lover—he cried when asked to kiss his bride. Within days of cohabiting, he wrote of his “intolerable spiritual torments.” The thought of her bathing he found so “totally repugnant” that he left their apartment and went to church to Mass to pray. “It appeared to me,” he wrote, that “the only good part of myself, that is, my musical talent, had perished irretrievably. My future rose up before me as some pitiful vegetation and the most insufferable and pedestrian comedy…death seemed the only way out.” He found his wife to be “an unbearable encumbrance,” “a terrible wound,” and spoke of drowning himself.

The couple separated in the fall after having lived together a total of thirty-three days: the marriage remained unconsummated. Tschaikovsky descended into an unprecedented state of emotional anxiety, a breakdown—possibly exaggerated by him and his family to justify his hasty escape.

Though she twice refused his requests to divorce, the couple never lived together again, but he supported her financially thereafter. By 1884 she had given birth to three illegitimate children with a lover, but she gave them up to an orphanage for pecuniary, health, and legal reasons.[*4]

All three children died before age eight.

Antonina Tschaikovskaya outlived her famous husband by twenty-four years, spending the last twenty of them in an insane asylum with “paranoia chronica” that included hallucinations and delirium. The lifelong pension from Tschaikovsky’s will paid for her keep. Her grave has long since disappeared.

A bare six months before his nuptials another woman had made herself known to Tschaikovsky. Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck was no dreamy, naive young woman in love but a formidable force who would change the composer’s life forever and is now inseparably melded to the music he left us.

Von Meck, at age forty-five, was nine years older than Tschaikovsky and recently widowed, leaving her an incredibly wealthy woman, when she first wrote to the musician whose work she much admired. Music was von Meck’s great passion, and she wanted something for herself—she was a pianist—and her in-house violinist to play for her own pleasure. The remuneration was handsome; inept with money, Tschaikovsky was ever in need and immediately complied, inaugurating a fourteen-year friendship.

After an elaborate confession to von Meck of his marital debacle, she offered Tschaikovsky a very generous yearly stipend of six thousand rubles (a civil servant at the time earned only three to four hundred rubles a year), which allowed the composer to renounce his teaching at the Moscow Conservatory and devote himself entirely to his composition.

“You know how I love you, how I wish you the best in everything,” she wrote with graceful insistence. “You know how many happy moments you have afforded me, how deeply grateful I am to you for them, how necessary you are to me, and how for me you must be exactly that which you were created to be. Consequently I am not doing anything for you, but everything for myself…so do not prevent me from giving my attention to your housekeeping, Pyotr Ilich!”

“Every note that will now pour out from under my pen,” he wrote to the woman he called “my own Providence,” “will be dedicated to you. Never, never, not for one second, while working, I will not forget that you give me the opportunity to continue my artistic vocation.” On another occasion, he demonstrated with startling directness their ease with each other, stating, “You are the only person in the world I am not ashamed to ask for money. First, you are very kind and generous; second, you are rich.”

While one cannot measure the exact effect this financial stability had on his output for the remainder of his life, it can be safely assumed that von Meck’s support gave us much music that perhaps otherwise would not have been made. This was patronage of the highest order—though it came with peculiar strings attached, or, more accurately, unattached.

Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck. “Music puts me in a state of intoxication,” she wrote. “One is mysteriously propelled…into a world whose magic is so great that one would be willing to die in this condition.”

Von Meck requested from the very start that they never meet in person. Tschaikovsky, suffering similarly from their mutual “illness” of “misanthropy,” agreed.

“My ideal man is a musician,” she explained. “The more I am enchanted by you, the more I fear acquaintance…I prefer to think of you in the distance, to hear your music, and to feel myself at one with you in it. Of my imaginary relationship with you…I will say only that this relationship, however abstract it may be, is precious to me as the best, the highest of all feelings of which human nature is capable.” She did, however, ask for a photo of him, and spoke of being “delirious” over his music.

Tschaikovsky, in accord, wrote back of “that disenchantment, that yearning for the ideal that follows upon every intimacy…I am in no way surprised that, loving my music, you are not attempting to make the acquaintance of its author…you would not find…that complete harmony between the musician and the man.”

On a single occasion, due to missed messages about a change in her daily schedule, they came face-to-face when he was out on one of his frequent walks while staying, at her invitation, in his own well-appointed house on one of her enormous estates. She, in her carriage, froze, and he just tipped his hat. Not a word was spoken, and both were shaken by the chance encounter.

“I am very unsympathetic in my personal relations,” von Meck wrote to her “beloved friend.” “I do not possess any femininity whatever; second, I do not know how to be tender.” This from the woman who had once written to Tschaikovsky of his marriage, “the thought of you with that woman was unbearable. I hated her because she did not make you happy; but I would have hated her 100 times more if she had.” Her years of devotion to Tschaikovsky belie in a stroke her claim that she lacked tenderness.

For over thirteen years, they wrote to each other weekly, sometimes daily, often at great length, resulting in an astonishingly intimate epistolary outpouring that produced (due to Tschaikovsky’s noncompliance with her request to destroy the letters) over twelve hundred letters that fill three volumes and offer an unprecedented window into the man behind the music.

In June 1880, Tschaikovsky received the suggestion to write a commemorative piece for an upcoming Moscow Exhibition to celebrate the Russian defeat of Napoléon in 1812. He was disgruntled at both the request to produce music glorifying “what [delighted him] not at all,” and the imprecise remuneration.

“My dear chap!” he wrote to Pyotr Jurgenson, his publisher. “You seem to think that composing ceremonial pieces for the occasion of an exhibition is some sort of supreme bliss, of which I shall rush to take advantage, and immediately begin pouring out my inspiration…I won’t lift a single finger until something is commissioned from me…(for a commission I’m even prepared to set Tchaikovsky music to the pharmacist’s advert for corn medicine)…There are two inspirations: one emerges directly from the heart with free choice of this or that motive for creativity; the other is to order. The latter requires motivation, encouragement and means of inspiration in the form of precise instructions, fixed periods of time and the prospect in the more or less distant future of (many) Catherines!”[*5] After considerable haggling, the composer agreed to the job.

On October 3, Tschaikovsky wrote to one of his brothers, Anatoly, that he had “started to write something”—but this was not the dreaded music for the Exhibition; this was Serenade. Uncommissioned, “from the heart with free choice.” Thanks to Tschaikovsky’s copious correspondence, one can track his progress to the day—and be astonished not only by the incredible speed of composition but also by the simultaneous juxtaposition of it with his work on the 1812 Overture, complete with its “platitudes and noisy commonplaces.”

On October 7, he told von Meck that he was writing a “suite for string orchestra,” and had already finished three movements. The first three movements of Serenade—Sonatina, Waltz, and Elegy—were thus composed in little more than four days! On October 12, he began the commission and finished that in just six days. Tschaikovsky acknowledged to his patron that he was on a roll: “Imagine, my dear friend, that my muse was so kind to me lately, that I wrote two things with great speed, namely: 1) a large solemn overture for the exhibition, at the request of Nick[olai] Gr[igorievich], and 2) a Serenade for String orchestra…The overture will be very loud, noisy—but I wrote it without a warm feeling of love, and therefore there will probably be no artistic merit in it. On the other hand, I composed the Serenade out of an inner urge; I felt it and therefore, I dare to think, is not devoid of real dignity.”

By November 4 Serenade was orchestrated—one month from start to finish—and a few days later he wrote to his publisher, “Pyotr Ivanovich! You have an unpleasant surprise in store. I accidentally wrote a Serenade for String Orchestra in 4 movements, and I’m sending it to you the day after tomorrow in the form of a score and 4-handed arrangement. I can see from here how you’ll be leaping up and exclaiming: thank you, I wasn’t expecting this! Whether because this is my latest offspring, or because it actually isn’t too bad, I just love this Serenade terribly, and I’m dying for it to see the light of day as soon as possible.”

The first page of Tschaikovsky’s handwritten score of Serenade. His note at the bottom reads: “The more numerous the instruments in the string orchestra, the more it will please the composer.”

On December 3, two months to the day that he began composing “something,” he was invited to a private concert at the Moscow Conservatory, his former place of work. “This piece [Serenade], which at the present time I consider the best of all that I have written,” he reported to von Meck, “was played by the professors and students of the Conservatory very satisfactorily and gave me considerable pleasure too.”[*6]

The great Russian pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein, long one of his severest critics, declared Serenade “Tchaikovsky’s best piece.” Tschaikovsky himself conducted his “favorite child” numerous times in his remaining years, including in Philadelphia and Baltimore during a celebrated tour to America in 1891, a trip occasioned by his invitation to the opening of Carnegie Hall.

The “detestable” 1812 Overture did not receive its premiere until August 1882, due to various delays, and it went on to become his most recognized work—thanks in part to Arthur Fiedler’s 1976 association of this very Russian, over-the-top-cannons-and-all pièce d’occasion with the totally unrelated American Independence Day of 1776. This is the score that made the Tschaikovsky estate very wealthy.

In 1890, von Meck mysteriously, suddenly, stopped Tschaikovsky’s yearly stipend and asked for no further contact. Having been given the honor of a yearly pension of three thousand rubles by Tsar Alexander III in 1888, Tschaikovsky was by now also making considerable money from his music, so while this did not threaten pending poverty, it was an incomprehensible cessation of the deep friendship that, he once wrote her, would “always be the joy of [my] life.”

While she referenced “bankruptcy” and various pressures from her family, she declined to mention that she was ill and her right hand had atrophied, making writing all but impossible.

In his final letter, he called her “the anchor of my salvation.”

Two years later, at age fifty-three, just nine days after conducting the premiere of his last masterpiece, Symphony No. 6 in B minor—the Pathétique Symphony—Tschaikovsky died. His cause of death continues, to this day, to be debated: the official Russian version has long been that he died of cholera (like his mother), but there is much evidence to suggest that it was suicide, related to the possible impending revelation of a homosexual liaison. Still further, there is credible evidence not only that he killed himself by purposefully drinking unsafe water during a cholera epidemic but also that he was ordered to commit suicide by an “honor court” of his peers from his days at the School for Jurisprudence. But whatever the truth, likely never to be known definitively, his reputation remained intact as the man who brought respect and fame to Russian music (as Tolstoy had brought respect and fame to Russian literature), and he had laid the musical foundation for the entire art of classical ballet. He was given a magnificent funeral, paid for personally by Tsar Alexander III, with a train of mourners over a mile long.

Balanchine believed fervently that Tschaikovsky had been persecuted due to his sexual orientation: “I believe that he wrote the Pathétique Symphony as a kind of suicide note,” he told Solomon Volkov. “He wrote it, then conducted the symphony himself; it was like coming back to life to see what people would say. He was preparing himself for his death…Tchaikovsky was a noble person. He did not want to involve people dear to him in a scandal. He couldn’t stand gossip around his name. Tchaikovsky gave in to society’s pressure, accepted its cruel laws—and left this life. They forced him to die.”

Nadezhda von Meck died just two months after her beloved Tschaikovsky. When her daughter-in-law, who was Tschaikovsky’s niece, was asked how von Meck had endured his death, she replied, “She did not endure it.”