20. MARIA’S ARABESQUE

The man, crouching behind the Waltz Girl, places both his hands under the Dark Angel’s long tulle skirt and around her leg, above the knee, holding her ramrod straight in place. Because the man is now invisibly supporting her, the Dark Angel can sustain her arabesque far beyond her own balancing abilities—though it is still a tricky situation. As if this magical arabesque on pointe were not enough, the man then rotates her supporting leg clockwise while she maintains her position. It is a magnificent event. While she is revolving, she not only holds her arabesque leg high behind her, perpendicular to her torso, but holds her head high too, as if balancing a crown, and her eyes face constantly forward—unlike “spotting” in pirouettes, where we keep our eyes on a single point in front of us and then quickly whip our heads back to that same point.

Rotating thus as a single entity, the Dark Angel magisterially maps the globe. She is sister incarnate to Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s weather vane of Diana, virgin goddess of women, slaves, nature, and the moon, who twirled for three decades at the turn of the twentieth century atop Madison Square Garden in New York, where her gilded body caught the sunlight and glittered for miles around.

The “Lady Higher Up,” as the writer O. Henry called Saint-Gaudens’s golden goddess, was commissioned by architect Stanford White in 1891 for his new design of Madison Square Garden, and White was infamously shot dead on the rooftop, just beneath Diana, fifteen years later amid a love triangle involving the beautiful young model Evelyn Nesbit. This Diana did not sport her usual tunic and boots but—scandalously in 1894—was nude. And she is slim, leggy, small-breasted, narrow-hipped, her hair gathered in a high bun, presaging not only what became known as a “Balanchine dancer” but more specifically his revolving Dark Angel in Serenade, as Diana balances in arabesque on a single demi-pointe, her scarf trailing, her bow drawn before her, like Cupid’s crossbow of love.

Saint-Gaudens’s Diana was, at the time, the highest point in New York’s skyline—forty-two feet taller than Lady Liberty. She was removed from her perch in 1925, and nine years later Balanchine echoed her in Serenade—probably unknowingly, as Diana had been taken down eight years before he arrived in New York. He reincarnated her revolution in the flesh.

The Dark Angel makes her full 360-degree inscription in space not just once, but then again, with increased risk, a second time—in case you missed round one. Repeats in ballet, as in music, are frequent and purposeful and often arrive in threes, but here it’s just two.

For the man and the Dark Angel, this arabesque double rotation is a tricky choreographic moment that can be fraught with trouble—mostly due to the fact that as he pivots her, however carefully he proceeds, the endless yards of tulle of her skirt will wrap into his hands, loosening his secure grip on her leg while also pulling on her skirt and threatening her already perilous balancing act on her right toe tips.

Balanchine did a version of this movement eight years earlier, in 1926, in a ballet for Diaghilev called La Pastorale, starring the elegant, endlessly leggy Felia Doubrovska. But for her—and in pre-1952 versions of Serenade—the skirt was short, so the audience could see the man’s hands turning her. Easier for the dancers, but not so mysterious as it is when his hands are hidden by tulle. This precarious turn is usually rehearsed a lot. A lot.

Minute 24:12.

Over the decades there have been some memorable Dark Angels, including Mimi Paul, Yvonne Mounsey, and Jillana. Maria Calegari was the reigning Dark Angel of Balanchine’s last years—my own time dancing the ballet. Her presence in our midst onstage was particularly felt in the amplified grandeur of her quiet authority. After Balanchine’s death, she continued dancing the role for yet another decade, during the fragile, transitional years of the company, during which his ballets became, for us, even more literally him. By the time Calegari retired, she had danced the Dark Angel almost one hundred times: it was imprinted in her DNA.

Born in Bayside, Queens, Maria is of Italian heritage, and like so many thousands of little girls, started classes at a local ballet school at age five. But this girl, unlike 99.9 percent of young ballet students, actually became a great ballerina.

Maria entered the big-league School of American Ballet in Manhattan at age fourteen and was invited by Balanchine to join the company at age seventeen, in 1974. She was promoted to soloist six years later, and became a lead dancer in 1983, the year of his death.

While this may sound like a smooth, steady rise to stardom, it was not, and Maria’s stall-stop-start struggle is illustrative of a certain alchemy wrought by Balanchine. He could make a ballerina out of a merely graceful, talented dancer. But he could not do it alone. A real ballerina is magic, but to become one, the dancer, the very rare one, must rise to the occasion and incarnate that tenuous entity called “promise.” Most of us, beautiful and accomplished as we were to even be chosen by Mr. B for the company, did not, could not, would not, go as far as Maria did.

Within two years of joining the company, she was cast by Mr. B in a few solo roles—the fierce and fast-spinning Dewdrop in The Nutcracker; the lead in the sultry, soft Elegy section of Tschaikovsky Suite No. 3; a tight, fiendish solo in Divertimento No. 15—and the Dark Angel in Serenade. It was an unusual, but not unprecedented, occurrence for a young dancer, fresh out of the School, to be singled out, but when Balanchine liked something, he abided by no rules of seniority, even less so any notion of “fairness.” He knew that budding talent needed immediate attention, how quickly a flower can blossom—or wilt. And he loved her name; Maria was his mother’s name. But soon after being showcased, she faltered and went into what she calls her “hibernation,” her “rest period.” Calegari says, “I wanted results without the work. I couldn’t handle the jealousy from other dancers. I also couldn’t handle his attention, so I gained twenty pounds.” Weight gain was often a sign in a ballet dancer, as it would be in an athlete whose profession resides in their body, that she was troubled, conflicted—a way, unconsciously, to put forward movement on hold. “I had a lot to work out,” she explains. “I was so insecure, and I hated the thought of being by myself on the stage. It was just too scary.”

Maria Calegari, age five, in her first tutu and ballet slippers, before a recital (© Richard Calegari)

Balanchine was frustrated with Maria’s inability to handle her own talent and its attendant pressures, and he stopped scheduling her in her various solos. Casting for Balanchine always told the real story, as he once said: “It’s all in the programs.” Maria went to Mr. B’s office for an explanation of his apparent withdrawal of interest.

“He really let me have it,” she says. “He told me the truth, is what he did. He said that dancing was 99 percent skill, not art. He told me I was too ‘fancy-schmancy.’ That I was trying to elaborate without getting to the nitty-gritty. ‘You have to work,’ he said. ‘You have to get in a room and you have to work. I can’t do it for you. You have to do it. You have to be able to jump; you have to be able to turn.’ Then he said, ‘You have no aura,’ which really killed me because that was the one thing I thought I had. He said, ‘If you want to do a matinee for your mother, I’ll give it to you. Or you can go to Ballet Theater and become a soloist.’ It was brilliant, saying everything that was against my real nature. He took a chance: I could react to this by going either straight up—or straight down. I started to cry, those sobs where you can’t control what you’re doing. As I cried, he said, ‘Now, dear, grown-up people do not get hysterical.’ Well, that just lifted me straight into reality. I remember leaving that room and that conversation and I began to change my life.”

Maria Calegari as the Dark Angel in 1974, age seventeen (Martha Swope © The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts)

Maria bit the bullet and started the real work Balanchine had referred to—with demonic focus. “I stuck it out. I lost the weight and I asked to reaudition for him for Dewdrop. He made me go through every entrance without a break—in actual performance there is time to recover between entrances. But he cast me again and started giving me my parts back.”

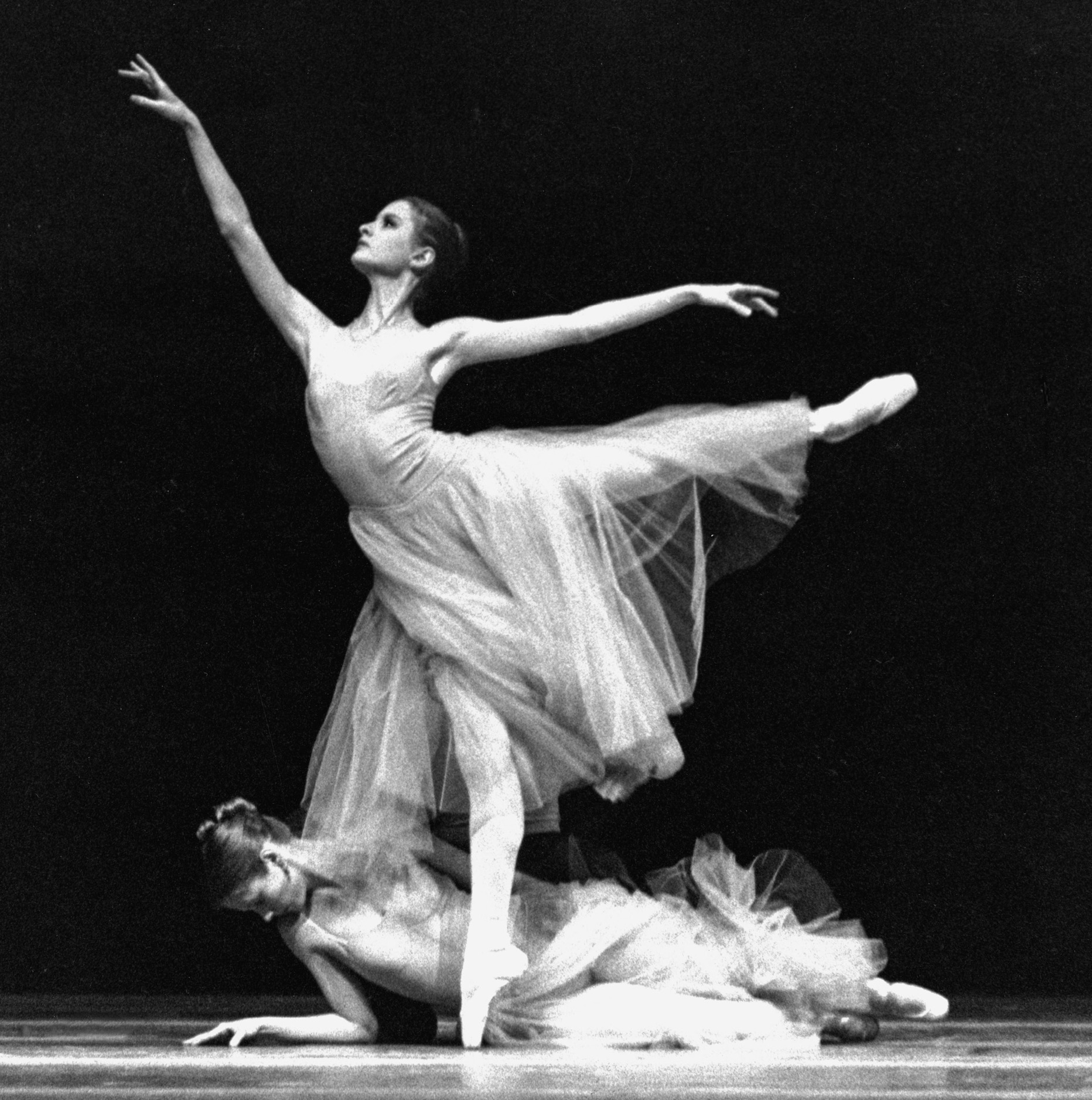

Maria Calegari as the Dark Angel in 1984 (© Paul Kolnik)

And so the butterfly was born of the chrysalis. How many dancers over Balanchine’s sixty years of teaching, of overseeing, encouraging the development of individual dancers, had such a life-altering talk with him? Many. But who among us could match the challenge to go even further than we already had? Maria.

In a telling visual, one can even view Calegari’s ascension to greatness from goodness, to beauty from sweetness, in two photographs of that same moment where she is the Dark Angel who circles the world. At age seventeen in the Workshop performance her position is precise and pretty, her clear lines resting on the space about her, a lovely lithograph. A decade later her limbs are amplified, cutting into the air, bending it, pushing it aside; her body is carving out space, commanding it, thus searing the sculpted dimensions into a viewer’s subconscious so that they remain there over time, perhaps forever. I can see her now before me. This kind of depth of movement—virtue embodied, fueled by soul rather than youthful duty—becomes, somehow, instantly identifiable as the gift of an utterly unique person, as if you have entered into their world rather than their passing through your own. It is the way one identifies the voice of Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley so instantaneously: we don’t just recognize them, we know them.

Despite the death of Balanchine midway through her career, Calegari managed, against many odds, to push through. He was gone just as she was entering that delicate realm where a beautiful dancer becomes a true ballerina, no longer a promising presence, a reliable soloist, or a dazzling technician, but a full-blown, engaged creature whose femininity so ascends as to attain unsurpassed dominion—and all of us onstage reside, with delight, in her monarchy. Others were not so able to proceed after he was gone and their careers halted, stalled, or occasionally regressed after his death, so essential was his daily vigilance, his mere presence providing the inside of the theater with an unavoidable, pervasive, silent oversight.

Even with Maria, we will never know how much farther, or in what directions, she might have traveled had he lived longer: her particular mysticism suggests a distinct loss. But, somehow, she inserted her sorrow into the abyss of his absence, and there she danced each night on the edge of the volcano, her beauty distilled by fragility, yet so sustained. And by then she was doing it entirely alone, so well had she—and her body—absorbed what he taught her. Her commitment was manifest, and she became the last of his ballerinas with true gravitas—and the glamour of a 1940s movie star. I see him giving that rare, barely discernible, nod of approval.

Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum.