21. VITRUVIAN MAN

Balanchine at a seminar, illustrating the vertical body, 1962 (© Nancy Lassalle/Eakins Press Foundation)

She and the pair behind her rise from their grouping and reassemble again toward the back of the stage, where they form a sandwich, all facing forward on a diagonal together. Their bodies are pressed tight, the man in the middle, securing each woman to him with an arm—the Dark Angel by the waist behind him, the Waltz Girl over her shoulder before him—and thus they walk forward as one. Right foot, left foot, right foot, left foot…Their intimacy is building.

After eight steps, they stop and turn to face the audience directly. They keep close, but the dynamic changes. Until now, the man has been blind, dependent, led, perhaps dominated, by the Dark Angel: even his apparent romantic interest in the fallen Waltz Girl takes place under her aegis. But now he shifts and becomes their center and, with his legs parted at shoulder width for stability, he takes in each hand the outer hand of each woman while they wedge their respective two feet together against the side of one of his feet for leverage. Each woman’s entire body weight is now secured against one of his legs. His arms are in a classic muscleman biceps flex and he slowly, slowly begins to lower their upright, barely bending bodies as he opens the right angle of his arms. And down they both go, one to his left, one to his right—down, down to the stage floor, each woman’s body tracing the soft lines of a protractor’s curve, each a side of the moon.

The man has become Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, his body the axis of symmetry, while the two women now mirror each other in a parity previously unclear. The dynamic of the Dark Angel leading him has given way to a different prospect.

This schema is dangerous and wondrous. The delicate nature of the triad is reflected in its physical tenuousness. Once elongated on the stage floor, the two women are in close proximity, and the two great pillows of tulle that amass about them as they descend are slippery, causing the risk of mishap when yet more women—yes, more, and soon—fly toward the man. In the late 1970s, Mr. B said at one rehearsal, to everyone’s astonishment, “I’m changing it!” (There had been too much skidding on the rogue tulle.) He then adjusted this Herculean display of coordination and male strength—particularly the biceps leverage—so that after only a brief leaning outward, each woman rescinds her dependence on the man and completes her own descent by lunging forward to one knee, lowering herself softly to the floor, tucking her skirt in close.

Vitruvian Man, by Leonardo da Vinci, 1490

This seemed a particular loss. But was it? One of the few moments in the entire ballet, in this land of women, where a man is unquestionably holding the center, the world, in his hands, was now gone. But Balanchine was ever serving the cause of the practical, knowing that the scaffolding of Serenade was indestructible by any single shift.

Suddenly a girl appears from the downstage-right wing (your left from the audience) and runs fast toward the man, who has just lost hold of his two consorts. She jumps over one floored dancer and her skirt, and he catches her by the waist as she leaps into a tour jeté, both legs kicked alternately skyward behind her as her body turns in space. He lifts her so high above him, over him, that she looks down upon him directly, like an angel floating. He lowers her down and she continues her diagonal trajectory offstage as if her brief conjoining with him was but chance, a mere detour while en route elsewhere. Another girl does exactly the same thing, though she enters from the opposite downstage wing. These two interjections are so swift and seamless that the airborne tulle of the dancers’ skirts wafts by, up, down, around, a mirage of blue smoke. This sole man is only beginning his negotiation of a steady bombardment of women coming at him—though we all are just passing through. Or is it he who is just passing by, like Albrecht searching for Giselle in the land of Balanchine’s Wilis?

Now the Russian Girl runs on, her loose hair trailing, and leaps madly toward the man in a large arabesque, pivoting in midair. He catches her as she flips forward. Drama is building here, through both surprise and risk. After the catch, he continues the momentum, carrying them both around yet again. Now facing you in the audience, she pirouettes, arms rising above her head as she turns twice. Remaining on pointe, held by the man at her waist, she extends her right leg into a high penché arabesque while reaching her left arm down to join hands with the Waltz Girl, who reaches her right hand upward toward her, though her body remains on the stage floor. The man extends his left arm across the front of the Russian Girl’s waist and similarly joins his hand to the Dark Angel’s right hand on the other side: all four dancers are now linked in several draping garlands of arms, an open figure eight of arms.

Minute 25:41.

There are only seven minutes and eight seconds left before the ballet ends. It is remarkable how much has yet to happen in this ballet of no story with plot to spare.

Six hands release, and the four dancers unwind; the Dark Angel and the Waltz Girl rise up, and the Russian Girl slips offstage yet again. The three are alone once more. But the women’s brief equality alters yet again, as each, from opposite sides of the stage, runs at the man alternately, while he stands center stage. As they approach him and he catches them about the waist, they swoop dangerously low in a plié on pointe with one leg, while the other is in attitude derrière. He carries one woman around in two fast circles in reverse before he releases her into fast, spinning chaîné turns back to her side of the stage. Then the other dancer repeats the same sequence with him. Then again one and again the other. This is no longer sisterly cooperation between the Dark Angel and the Waltz Girl, nor is the Dark Angel in charge: this is now all but open warfare, unveiled competition between the women for the man. But he receives each in succession with grace—choosing neither, accepting both.

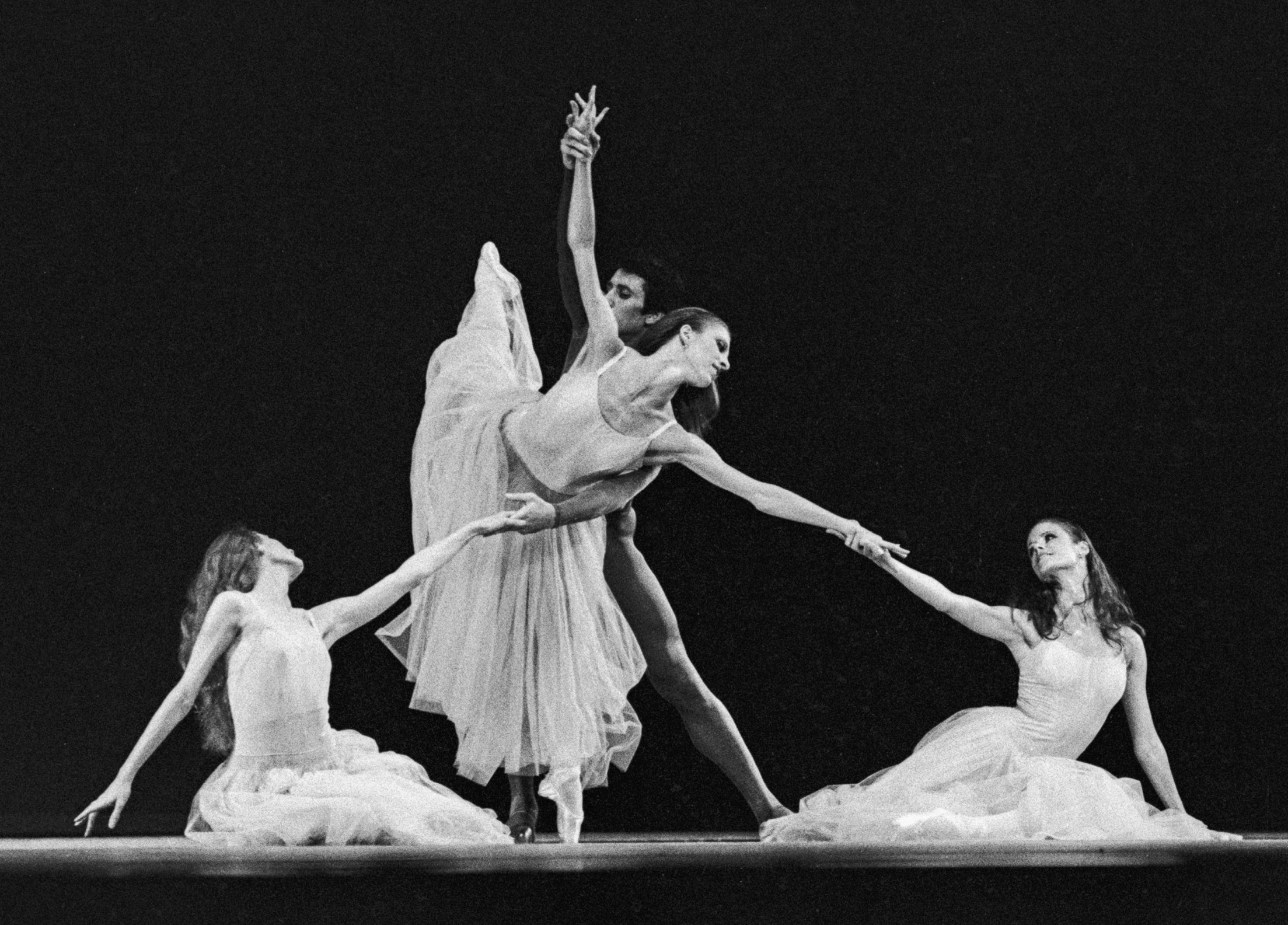

Draping garlands of arms (from left: Maria Calegari, Kyra Nichols, Leonid Kozlov, and Merrill Ashley) (© Paul Kolnik)

Then, in another shift, the women parallel each other again in united purpose, each taking one of his arms and pulling him to the back of the stage on a diagonal, clearly restraining him as he looks to escape. He pushes forward as they attempt to hold him back, and just as they release his hands for a moment, two more dancers run toward him. He lifts the second in a high arabesque before she continues her speedy exit offstage. I was one of these who was lifted, and it felt like a surreptitious interruption of the adults in the midst of their grown-up complications. And then all this again: the restraining of him, the letting go of him, his brief interaction with two other women passing through. The Russian Girl reappears and the Waltz Girl and Dark Angel clear the stage for her, assembling close together upstage right. But this is no ordinary entrance.

She runs in fast from the downstage-front wing, Mr. B’s wing, toward the man, and leaps. Shooting her right leg straight skyward in a large, lush développé. As she starts to tip behind herself, he leans forward, legs wide, and lands her on his lower back, his right arm reaching behind him to secure her waist. It is an extraordinary leap-and-catch, resulting in her right leg pointing up, past perpendicular, her left leg extending in opposition. Splayed in 180 degrees, she is upside down, her hair spilling to the stage floor. And then the man lets go with his right arm (not all dancers manage this last release), extending both his arms to the sides: free. Her entire body is now balanced, her lower back over his lower back like a seesaw, her lever to his fulcrum. My God.

During my era, a particularly passionate Russian Girl was a dancer whom Balanchine would have called one of his “nuts and raisins”; these were dancers who defied the parameters of the so-called “Balanchine dancer”—though he always denied there was such a thing. As he would have it, the single criterion for a Balanchine dancer was that he liked her—liked her dancing, found her beautiful. Thus there were dancers who were more voluptuous—like the glorious Gloria Govrin—or spikier, like the chiseled Wilhelmina Frankfurt. Or smaller and more classically romantic in demeanor like the pale, brunette Nichol Hlinka, our Russian Girl. Short by the usual company standards, she was a strong dancer, with a huge jump and the Carla Fracci–like femininity of a nineteenth-century Giselle. Her trajectory to principal dancer was full of pit stops and time-outs, and it took some years for her to bloom. Mr. B said dancers were like flowers, and not only did we all blossom on different schedules but some opened more fully than others, lasted longer than others. Most remained only buds—still beautiful, but not a dominant bloom. I was one of these.

Mr. B focused intensely on Nichol during her first years in the company—but it was not her time. She had rebellion to spare and was not always able to follow his lead. But she remained dancing in the corps throughout, and pressed forward after his death, becoming only then a leading light in the company. This put her, like Maria Calegari, in the unique category of what, to me, a true Balanchine dancer came to mean—dancing as he taught, as he loved, long after his death. Once Nichol did find her way, she was fiery and fearless, the rebellion utterly intact but focused into onstage power. When she leapt as the Russian Girl in Serenade from too far away, both legs splayed upward, her abandon had a wildness that always made me see his love for this gorgeous woman made visible—as was her love for him. And because he was not in the wings to see it, her leap of faith was not only literal, physical, but true.

Nichol Hlinka and Kip Houston (© Paul Kolnik)

The Russian Girl is swung back upright, steps into an arabesque on pointe, runs around, and spins about in the man’s arms, before he slides her back and then forward on her pointe tip, holding her in an extravagantly lunging penché…the movements are relentless and full and fast. Now, unlike in her previous entrance, when the Waltz Girl and the Dark Angel presided, the Russian Girl does not leave the stage; she stays. They are a man and three women, a neat quartet.

I have wondered if this could be the exact gathering Mr. B was referring to when I visited him in the hospital at the end of his life when he suggested I write about a “man and three women.” I must doubt it. Apollo is also the story of a man and three women, and there are numerous other moments, groupings, dances in his ballets where a man and more than one woman dance together. I think he was speaking to me that day of the story that interested him most—an artist and his muses—the story that was his life, his only story. I see his ballets as but the outpouring, the shedding, the emanation, and the elucidation of his enduring, all-consuming devotion to the mystery of the female sex. Their beauty his engine.