Considering modern societies’ obsession with economic growth, it is surprising how little attention is paid in public debate and political discourse to the question of whether more economic growth actually increases wellbeing. Perhaps this avoidance is convenient for those who have a stake in the prevailing system: if growth does not improve wellbeing, many of the economic, social and political structures of advanced capitalism cannot be justified. Perhaps ordinary people too have a stake in ignoring the evidence on growth’s effects on wellbeing. When people are persuaded that more income will make them happier, they typically react to the disappointment that follows the attainment of that income by concluding that they simply do not have enough. This is a cycle without end—hope followed by disappointment followed by hope—unless some event or sudden realisation breaks it.

In fact, there is now a large body of evidence that casts serious doubt on the dual assumptions that more economic growth improves social wellbeing and that more income improves individual wellbeing. It is a body of evidence systematically ignored by policy makers and most economists, yet it is consistent with folk knowledge, accumulated through the ages, that money cannot buy a happy life. Not only does the evidence cast doubt on the growth assumption; it also points to the factors that do contribute to individual and social wellbeing. Although many of the factors that cause people to be more or less happy are beyond the influence of governments or communities, some of them are not. From a policy point of view, if we know what improves wellbeing we can know better what to emphasise. We know that there is a general assumption that increasing people’s incomes will make them happier and that as a result increasing the rate of economic growth is vitally important. But the question, even in economic terms, is much more complex. If rising incomes result in increasing happiness then we would expect three relationships to hold:

• People in richer countries will be happier than people in poorer countries.

• Within each country, rich people will be happier than poor people.

• As people become richer they will also become happier.

What is the evidence for each of these? While acknowledging that part of the problem is the way in which consumer society has redefined our understanding of happiness, for the time being we assume that the meanings of ‘happiness’ and ‘life satisfaction’ are understood.

To start to answer these questions, a number of studies have compared average levels of reported life satisfaction across countries with varying levels of national income per person. At the national level, there is a weak positive correlation between a country’s income and self-reported life satisfaction. This relationship may, however, be due to factors other than national income but that are themselves correlated with national income—such as the presence of political freedom and democracy, and tolerance of difference. Some evidence also suggests a negative relationship between income and happiness. For example, within Asia, residents of wealthy countries such as Japan and Taiwan regularly report the highest proportion of unhappy people, while the countries with the lowest incomes, such as the Philippines, report the highest number of happy people.1

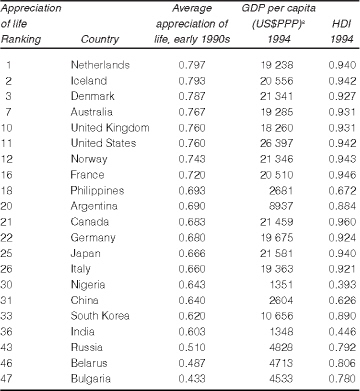

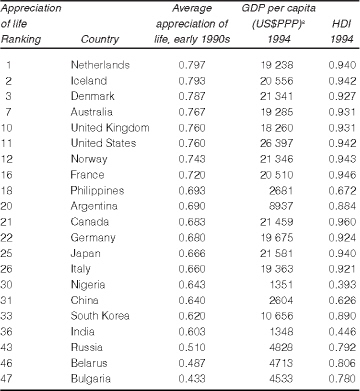

Table 1 shows reported levels of ‘average appreciation of life’, on a scale of 0 to 1, for a selection from 48 nations for which data are available. Measures of life satisfaction are based on self-reported perceptions of happiness. The first column shows the ‘happiness’ ranking of each country. The figures on average appreciation of life apply to the early 1990s. The other columns show real GDP per capita in 1994 and the Human Development Index, an index constructed by the United Nations Development Program that includes measures of life expectancy and education levels as well as per capita incomes.

Table 1 Appreciation of life, GDP and Human Development Index: selected countries, early 1990s

a. Exchange rates converted to US$ at purchasing power parity.

Sources: Appreciation of life—A. Wearing & B. Headey, ‘Who Enjoys Life and Why? Measuring Subjective Wellbeing’, in Richard Eckersley (ed.), Measuring Progress: Is Life Getting Better? (CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood), Table 1; GDP and HDI–UNDP, Human Development Index (<www.undp.org/hdro/98hdi.htm>)

The figures suggest that Dutch people are the happiest in the world and Bulgarians the most miserable. Perhaps the Bulgarians are naturally lugubrious, or perhaps the survey was done during a dark chapter in their history. It is apparent that, while there is a tendency for wealthier nations to be higher on the scale of appreciation of life, there are many cases where a country with a much lower per capita GDP ranks higher than countries with much higher per capita GDP. The correlation between the two is not strong.2 If we take the top 17 ranked countries, with per capita incomes ranging from $16 000 to $34 000 (not all shown in Table 1), there is no relationship at all between higher incomes and higher reported appreciation of life.3 Another study indicates that there is a threshold level of around US$10 000 above which a higher average income makes no difference to a population’s reported life satisfaction.4 As noted, Table 1 also lists the 1994 Human Development Index for a selection from the 48 countries (for the early 1990s). Perhaps surprisingly, this index—one that includes measures of education and life expectancy as well as income—does not do any better than GDP as a proxy for appreciation of life.5

Overall, the figures suggest that it is unlikely that in itself additional income makes much difference to wellbeing in developed countries. Other social researchers have tried to relate levels of subjective wellbeing to various characteristics of a nation. Among the factors associated with higher levels of happiness are knowledge, industrialisation, civil rights and tolerance. Among the factors associated with lower levels of happiness are unsafe drinking water, the murder rate, corruption, lethal accidents and gender inequality.6 These suggest priorities for government policies and changes to the social structure that would put increasing the growth rate of GDP well down on the list.

Obviously, income matters a great deal for people living in poverty. There are powerful arguments for more economic growth in countries where a large proportion of the populace lives in poverty. But this should not be construed as an unalloyed endorsement of growth at all costs. The nature of the growth process matters. Increases in average income often conceal widening inequality, and in countries undergoing industrialisation large numbers of people are thrown out of rural impoverishment into a worse condition in the informal economies of the cities. In addition, millions of people who have climbed their way out of poverty have been plunged back into it by economic collapse, with no safety net and in an even more parlous situation than when they had a plot of land to fall back on. When a nation is above the threshold below which increasing income does improve wellbeing, it is no longer persuasive to argue that more growth is needed to conquer residual poverty. Rich nations have been rich for a long time but the residual poverty has become intractable. Indeed, in most industrialised nations (and certainly the Anglophone ones), by some measures poverty rates have risen in the last two decades despite the fact that incomes have continued to grow.

The question of the relationship between inequality and improvements in wellbeing is less clear-cut than that of the relationship between poverty and growth. In general, more equal societies are more happy societies. In a review of the evidence, Michael Argyle notes studies that conclude that income equality is a stronger predictor of national happiness than income levels.7 There are two sets of reasons for believing this. First, a body of evidence shows that, with respect to income, people judge their wellbeing not by the absolute amount of their income but by its relative level. Thus psychological wellbeing is shown to depend not on one’s level of income but on the perceived gap between one’s actual and desired income, one’s actual and expected income, and one’s actual income and the incomes of others.8 Richard Easterlin, who did much of the early work in this field, referred to a ‘hedonic treadmill’, on which people have to keep running in order to keep up with the others, but they never go forward. Thus, even if rich people were significantly happier than people with moderate incomes, this does not mean that raising the incomes of the latter group would make them happier. If the rich have become richer still, no one is better off. The rich would need to become less rich. Other studies suggest that, as incomes rise, income and economic factors become less important in welfare. This has been described by the British economist Sir John Hicks as the ‘law of diminishing marginal significance of economics’.9 The second reason is that more equal societies are happier societies because even in rich countries inequality itself has been shown to be associated with increased ill-health. It seems hard to sustain the view that people in richer countries are happier than people in poorer countries.

What of our second question: Are rich people happier than poor people? There is evidence from an array of studies relating individual or household incomes to levels of happiness or wellbeing. The evidence shows that, beyond a certain point, increased income does not result in increased wellbeing.10 In other words, the rich do not appear to be happier than those who have a moderate level of income. The direct evidence on the relationship between income levels and happiness is extensive.11 In the United States there is virtually no difference in reported satisfaction between people with incomes of $20 000 and $80 000. In Switzerland the highest income group reports a somewhat lower level of happiness than the income group just below it.12 The poor, as opposed to those on moderate incomes, do have significantly lower levels of wellbeing than the rich, although the difference is not large. In poor countries such as Bangladesh, wealthier people have higher levels of wellbeing than poor people. But in rich countries, having more income makes surprisingly little difference.13 A survey of the 100 people on the Forbes list of wealthiest Americans, each with a net worth exceeding $100 million, found only slightly higher levels of subjective wellbeing than a sample of ordinary people drawn from the telephone book. When asked about the sources of their happiness none of the wealthy group claimed that money is a major source of happiness; they more often mentioned self-esteem and self-actualisation as the sources of wellbeing.14 According to the authors of the study, ‘One fabulously wealthy man said he could never remember being happy. One woman reported that money could not undo misery caused by her children’s problems. Examples of the wretched wealthy are not hard to come by—Howard Hughes, Christina Onassis, J. Paul Getty’.15 In the United States, there are now counselling services for the rich and their children, providing advice on how to deal with the psychological damage caused by great wealth.

If more income results in more happiness we would expect a growing nation to report increasing levels of life satisfaction over time. Data for Japan show that in the period 1958 to 1991 real GDP per person increased sixfold, yet reported satisfaction with life did not change at all.16 In the United States, where consistent surveys have been conducted since 1946, real incomes have increased by 400 per cent, yet there has been no increase in reported levels of wellbeing.17 Indeed, the proportion of Americans reporting themselves to be ‘very happy’ declined from 35 per cent in 1957 to 30 per cent in 1988, while the percentage who said they agreed with the statement that they were ‘pretty well satisfied with [their] financial situation’ fell from 42 to 30 per cent.18 This is astonishing: despite a trebling of real incomes during the period, fewer Americans in the 1990s are satisfied with their incomes than was the case in the 1950s. The implications of the figures cannot be brushed aside: if a sharp rise in personal incomes does not result in any increase in reported life satisfaction, why do we as societies give such enormous emphasis to economic growth?

One answer to this conundrum can be found in figures presented by Juliet Schor in her book The Overspent American. Schor reports that 27 per cent of households with incomes of more than $100 000 a year say they cannot afford to buy everything they really need. ‘Overall, over half of the population of the richest country in the world say they cannot afford everything that they really need. And it’s not just the poorer half.’19 Moreover, more than a third of those with incomes of $50 000 to $75 000 say they spend nearly all of their income on the basic necessities of life. A similar study in Australia in 2002 found that among the richest 20 per cent of households, 46 per cent said that they could not afford everything they really need.20 Schor also reports on a poll conducted in 1986, in which Americans were asked how much income they would need to fulfil all of their dreams. (Notice the assumption on which the question is based.) The answer was $50 000. Eight years later the figure had risen to $102 000.

Further insight into the relationship between national income and wellbeing can be gained from a 1992 study comparing living standards in Japan and Australia.21 Japan has a substantially higher level of per capita GNP than Australia, but does this make Japanese people better off? In the 1990s it was often pointed out that Japanese per capita income was almost the highest in the world and that for some decades other countries had been falling behind. In his analysis of Japanese and Australian living standards, Castles observed that the usual comparisons are based on estimates of real expenditure per person, so he set out to make a more comprehensive comparison of living standards in Sydney and four Japanese cities—Tokyo, Kanagawa, Kyoto and Osaka. The Japanese cities have population densities about five or six times greater than that of Sydney, and people in the Japanese cities have much less private and public space. The dwellings are less spacious than those in Sydney (75 square metres compared with 139 square metres), and they are on allotments of land only a quarter the size. The provision of public amenities—in the form of parks, roads, school grounds, hospital grounds, and sporting facilities—is much higher in Sydney than in the Japanese cities. While Japanese city dwellers enjoy around 250 hectares of public open space per million of population, Sydneysiders have over 4000 hectares, and while Japanese have 32 playing fields per million of population, Sydney residents have more than 500.

These facts have a major bearing on living standards. Another vital question concerns how much time Australians and Japanese must sacrifice in order to sustain their levels of consumption. Whereas Sydneysiders worked around 35 hours a week (males, 38.5; females, 30), Japanese city dwellers worked around 47 hours each week (males, 50.5; females, 41), suggesting that higher incomes in Japan are acquired at a high cost in terms of overwork.22 One way to look at this is to calculate the cost of a basket of foodstuffs measured in hours of work. Whether measured in terms of either a Japanese or a Sydney basket, Japanese city dwellers must work more than twice as long as Sydneysiders. The results represent a biased picture of living standards to the extent that foodstuffs are relatively more expensive in Japan, but the cost in hours worked of most other goods and services is also higher in Japan than in Australia, although by a much narrower margin.

Castles concludes that, while the growth rate of per capita income has been much faster in Japan than in Australia for some decades, Australians ‘continue to enjoy higher real consumption levels per capita, in respect of virtually every significant category of expenditure. This was true notwithstanding the facts that they worked fewer hours each week, took longer holidays and had shorter working lives’. The comparison of Japan and Australia tells us that income per person can be a very misleading indicator of wellbeing, even when considered only in material terms. At a minimum, we need to know the conditions under which that income was generated and the circumstances in which it is consumed. The discussion of ‘the emptiness of Japanese affluence’ is taken up again in Chapter 3, but the study just summarised poses the question of whether people in Japan would have been happier if they had exchanged some economic growth for more time.

On the basis of the evidence reviewed here, it is reasonable to draw the following broad conclusions: above a certain level of national income people in richer countries are no happier than people in poorer countries; in any given country rich people are no happier than those with moderate incomes; and as people become richer they do not become happier. These conclusions need to be tempered by the observation that more income does make a difference to people who are very poor and lack the basics of food, shelter and health care. But this does not change the fundamental observation that in rich countries increasing incomes through more economic growth does not improve levels of national wellbeing. Moreover, the economic structure and policies that maximise growth come at the expense of measures to improve the lot of the residual poor.

A deeper understanding of the aetiology of happiness can be gained by considering the relationship between levels of happiness and the personal characteristics of people. There is an extensive psychological literature on this question. Myers and Diener summarise the results from a large number of studies and conclude that there are four traits characteristic of happy people.23 First, they have high levels of self-esteem and usually ‘believe themselves to be more ethical, more intelligent, less prejudiced, better able to get along with others, and healthier than the average person’. Second, they tend to feel more in control of their lives. Those with little control—those trapped in poverty and citizens living under authoritarian regimes—tend to be more despondent and less healthy. Third, happy people tend to be more optimistic. Fourth, they are more extroverted.

More detailed research has broken down the variation in happiness levels between individuals into several components. Personal psychological factors (such as those just mentioned) explain 30 per cent of the variation in levels of happiness. Life events such as divorce, the birth or death of a child, and illness account for a further 25 per cent. Social participation, including voluntary activities, paid work and marriage, account for another 10 per cent. It is surprising to discover that income and material wealth account for only about 10 per cent of the variation in personal levels of happiness.24

Further evidence on the chimerical effect of wealth is provided by studies of lottery winners. A study of winners of major lotteries found that they were no happier than a control sample but that they took significantly less pleasure in mundane events.25 Although there is an immediate lift in mood, the euphoria is temporary and activities that previously gave pleasure, such as reading, may become less pleasurable. Summarising this research, Myers quotes the author of these studies—‘Happiness is not the result of being rich, but a temporary consequence of having recently become rich’—and notes other work that confirms that ‘those whose incomes have increased over a 10-year period are not happier than those whose income has not increased . . . Happiness is less a matter of getting what we want than of wanting what we have’.26 On the other hand, gambling plays a powerful part in social control by promising a way of breaking out of the constraints of everyday life. For many people, living in the hope of a chance external intervention deprives them of the motivation to change their personal or community circumstances.

These studies show that, in general, social relationships, including relationships with family and friends, are the most important determinant of happiness. They also show that married people tend to be more happy than divorced (or separated) people. While unemployment is a source of great unhappiness, job satisfaction is very significant as a source of happiness, as is ‘serious or committed leisure’ (as opposed to passive television viewing). Religious belief is also a very important source of happiness for some. In one of the most thorough investigations of the determinants of happiness, the researchers came to a startling conclusion: ‘A sense of meaning and purpose is the single attitude most strongly associated with life satisfaction’.27 I return to this later because it demands a deeper consideration of the notions of happiness and wellbeing than has underpinned the discussion so far.

The studies described generally find that personal happiness is heavily influenced by relative factors. Personal happiness depends on what people have compared with what they want, what they expect, and what other people have. This leads naturally to an exploration of the goals people set for themselves. In other words, the determinants of happiness are not simply given and immutable—part of the human condition and therefore beyond influence by social organisation and public policies. The goals people set are strongly influenced by social expectations, which can change rapidly. A large body of psychological research shows that these goals have a major bearing on people’s subjective wellbeing. In 1998 three psychologists reviewed the evidence:

There is a substantial research base that demonstrates that people’s priorities are prime determinants of their wellbeing, and that these priorities are based on their current and long-term goals, projects and concerns . . . The goals people strive for, the manner in which they strive for them, and their ability to integrate the goals into a reasonably coherent framework influence their subjective wellbeing.28

The psychologists reported that people whose goals emphasise intimacy and affiliation with others (reflecting ‘a concern for establishing deep and mutually gratifying relationships’) have higher levels of wellbeing than those whose goals emphasise power (reflecting a desire to have an impact and influence on others). Statistically, the associations between types of strivings and wellbeing are only modest. However, conflict between personal goals—a situation in which attainment of a primary goal interferes with the ability to attain another goal—is strongly related to diminished wellbeing. Trying to spend more time with one’s family while doing well in one’s career is a good example of a goal conflict that will cause distress, especially if the conflict becomes chronic and is associated with poorer psychological health and physical ill-health.

In a series of studies, some published in leading journals, Kasser and Ryan distinguish between two sets of beliefs about the sources of happiness.29 The first is the belief that the path to happiness lies in the pursuit of the external goals of wealth, fame and physical attractiveness. The second is that happiness grows from striving for deeper relationships and personal growth and from contributing to the community. The first set of beliefs is a self-focused system, one in which happiness is derived from extrinsic material rewards. Clearly, this is the modern myth of the consumer society: we are bombarded daily with images and messages that try to persuade us that we can find contentment and fulfilment by acquiring this product or that one or by pursuing a perfect body image or clawing our way up the corporate ladder. Thus we celebrate the wealthy, the powerful, the famous and the beautiful.

After classifying individuals according to whether they operate on the basis of a belief in extrinsic goals (money, fame and beauty) or intrinsic goals (relationships and personal growth), the researchers then ask which group is happier. The conclusions, summarised by Tim Kasser, are unambiguous: ‘Individuals oriented towards materialistic, extrinsic goals are more likely to experience lower quality of life than individuals oriented toward intrinsic goals’. But the news gets worse. Not only are those with extrinsic orientation in life less happy than those with intrinsic goals; they make others less happy too:

Further, extrinsically oriented individuals are shown to have shorter, more conflictual, and more competitive relationships with others, thus impacting the quality of life of those around them. In sum, the pursuit of personal goals for money, fame and attractiveness is shown to lead to a lower quality of life than the goals of relatedness, self-acceptance and community feeling.

The four traits of happy people that Myers and Diener identified—self-esteem, control over one’s life, optimism and extroversion—are also associated with close personal relationships. People who can name several intimate friends are healthier and happier than those who have few or no close friends. As noted, married people tend to be happier than unmarried people, although there is a risk of a period of great unhappiness if the marriage founders. In the United States around 40 per cent of married people say they are ‘very happy’, while only around 25 per cent of those who have never married report being very happy.

These studies confirm what many people know intuitively—that the goals of wealth, fame and attractiveness are hollow. They show that when people pursuing these goals achieve them they do not feel any better as a result. Indeed, the research shows that people who have extrinsic goals tend to be more depressed than others, and they suffer from higher levels of psychological disturbance as well as scoring lower on measures of vitality and self-awareness. One study found that teenagers in a high-risk group who put great stress on financial success were less likely to contribute to their communities and more likely to engage in antisocial behaviour such as muggings and vandalism. Another study found that extrinsically oriented individuals had briefer, more narcissistic relationships and their romantic attachments were marked by more jealousy and less trust: ‘This is a particularly poignant finding, especially when one considers that behind an extrinsically oriented individual’s behavior may lie a desire to be loved and admired’.30 On the other hand, those who have intrinsic goals concentrated on closer relationships, self-development and helping others improve their levels of wellbeing as they attain their goals. Although this research program focused on the United States, the results are beginning to be replicated in other cultures, notably Germany, Russia and India.

The researchers provide further insight into the relationship between goals and wellbeing. Longitudinal studies show that people who make progress towards reaching intrinsic goals experience improved wellbeing, while those who attain their extrinsic goals are no happier.31 In other words, if our relationships improve we become happier, but if our bank balance grows we do not. Moreover, people who invest themselves in the external goals of wealth and fame are distracted from attending to their intrinsic needs and find themselves in situations characterised by ‘more ego-involved, controlling and competitive settings that themselves can ‘undermine’ intrinsic satisfactions’. In an observation with profound implications for consumer societies, Kasser and Ryan write:

Procuring externally visible outcomes that convey ‘outer’ worth thus may reflect a compensatory attempt to obtain a sense of ‘inner’ worth . . . [One study showed] that adolescents who were more materialistic came from maternal-care environments that were less nurturant . . . environments characterized by cold, controlling maternal care.

I explore the relationship between family structure and consumption habits later. Kasser and Ryan also show that individuals with extrinsic orientation use drugs, cigarettes and alcohol more frequently and that these may be a form of self-medication to cope with their less satisfying lives or lower self-esteem.32 It is also apparent that levels of television watching are especially related to extrinsic goals, a relationship that may be explained by television’s role as a stress reliever or its power to induce a greater orientation to goals of wealth and fame. There is experimental evidence to support the latter interpretation.

The authors of these studies—staid, careful psychologists—draw a radical conclusion, one that presents no threat as long as it remains safely confined to the academic literature: ‘Thus it appears that the suggestion within American culture that wellbeing and happiness can be found through striving to become rich, famous, and attractive may themselves be chimerical’.33

The implications of this research for public policy and social development could not be more far-reaching. The results strongly suggest that the more our media, advertisers and opinion makers emphasise financial success as the chief means to happiness the more they promote social pathologies. This is why the researchers gave their papers such titles as ‘Be Careful What You Wish For’ and ‘A Dark Side of the American Dream’.

Although the citizens of rich countries have attained unprecedented levels of personal wealth, they are also afflicted by an epidemic of psychological disorders. According to one study, depression has increased tenfold among Americans born since the Second World War.34 Young people, the principal beneficiaries of super-affluence, are most prone to clinical depression, evidenced in record rates of teenage suicide and other social pathologies such as self-destructive drug taking. The risk of major depression is two or three times higher among women than among men, but the gap is closing because of the faster increase in the incidence of depression among young males. These trends are evident across rich Western countries—including the United States, Canada, Sweden, Germany and New Zealand—but not in Korea or Puerto Rico.35

According to the World Health Organization and the World Bank, the burden of psychiatric conditions has been greatly underestimated. Of the ten leading causes of disability worldwide in 1990 (measured in years lived with a disability), five were psychiatric disorders—major depression (the number one cause), alcohol use (fourth), bipolar disorder (sixth), schizophrenia (ninth) and obsessive-compulsive disorders (tenth).36 Major depression is responsible for more than one in ten of all years lived with a disability. The burden is greater in, but by no means restricted to, the rich countries. While major depression is already the leading cause of disability worldwide, when measured in terms of disability-adjusted life-years it is expected to leap from being the fourth most burdensome disease in the world in 1990 to second place in 2020. In rich countries, one out of every four disability-adjusted life-years is lost due to psychiatric disorders, which is an astounding burden of mental ill-health. In developing countries, psychiatric disorders are fast replacing traditional infectious diseases as the leading causes of ill-health.

Reflecting a 19th century preoccupation with mortality rates, the critical role of neuropsychiatric disorders in community wellbeing has been ignored because they are absent from the list of causes of death. Moreover, psychiatric disorders are frequently misdiagnosed and improperly treated as physical disorders because of the general social fixation on correcting deviations from a happy ideal rather than acknowledging widespread social distress. Mental health care does not generally require sophisticated equipment and invasive medicine; it requires properly trained, suitable professionals with plenty of time to deal with each patient.

Although researchers have been effective at mapping the increasing incidence of major depression, they have been unable to explain it. They identify vague risk factors (including in one case ‘being a female adolescent’) but are yet to explore them. It is known that a person’s chances of suffering from depression are greater if they are impoverished, unemployed or living in a dysfunctional family, if they have been abused as a child, or if they have a family history of mental illness. Other studies suggest broader social changes that probably get closer to a social explanation and avoid focusing on problems with individuals. They mention urbanisation, geographic mobility, changes in family structure, and the changing roles of women. But one factor stands out in the discussion of the aetiology of depression and solutions to it: social isolation. The erosion of social connectedness—manifested in loss of face-to-face contact, the change in family structures, the transformation of workplaces, and the commercialisation of community activities such as sport—and the consequent deterioration of relationship skills lie at the heart of the epidemic of mental illness. The problem then becomes how to explain it. What is the explanation for the erosion of social connectedness and the pervasive loneliness of modern societies?

People who are obsessed by the accumulation of wealth necessarily focus on their own circumstances and those of their immediate family. Focusing on one’s own perceived needs means an inward psychological orientation, so that the needs of others fade into the background. Moreover, the pursuit of wealth is inherently competitive: success demands that one elbow out rivals; one’s own superiority depends on the inferiority of others. People who pursue wealth put themselves under time pressure, so that they lack time to devote to activities that build communities, including simple activities such as talking to neighbours and taking an interest in the rest of the world and its travails. Finally, people who are preoccupied with money and material acquisition have a psychological affinity with things rather than with relationships, and their relationships are more likely to be structured so as to assist the quest for accumulation. Relationships with family, friends and the wider community are mediated through materialist objectives. This is the story of postwar consumer capitalism.

Depression is not the only unexplained psychological disorder in wealthy societies. Increasing numbers of people are easily distracted, find it difficult to concentrate on the task before them, have difficulty listening to what is being said, talk too much, cannot sit still for more than a few minutes, and are drawn to physically dangerous activities without considering the possible consequences. In fact, these are the signs listed by the American Psychiatric Association as characterising attention deficit disorder (also known as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder). Rates of diagnosis of ADD in the United States grew extraordinarily in the 1990s. No one knows what ‘causes’ this disease, which predominantly affects white middle-class boys, but there is a suspicion that ‘toxins, environmental problems, or neurological immaturity’ could be responsible.

The response to ADD says as much about the modern world as the rise of the disorder itself. The answer has been drug therapy. Prescription of Ritalin, a powerful stimulant derived from the cocaine family, increased by 700 per cent in the United States between 1990 and 1999, with between 4 and 5 million children taking the drug regularly. In some schools, 20 per cent of fifth-grade boys take daily doses of Ritalin and—in an eerie reminder of mental hospital routine—teachers line up bottles of medication, clearly marked by name, so that children can be doped to get through the day. Ritalin masks some of the symptoms of ADD and has given rise to side effects known as ‘Ritalin rebound’, including weight loss, insomnia, facial tics and a ‘sense of sadness’. It is increasingly used as a recreational drug by teenagers and college students, who refer to it as ‘vitamin R’. Crushed and snorted like cocaine, it gives a rush and helps when cramming for exams.

Although a small number of children do require drug therapy, the boom in prescription of Ritalin reflects expectations of children in a society in the grip of the growth fetish. Lawrence Diller, a physician whose book Running on Ritalin exposes the misuse of the drug, links the frequency of diagnosis of ADD and the explosion in prescription of Ritalin to social changes in the community. Classrooms and child-care centres are now pressure environments. In the 1970s only 30 per cent of mothers of young children worked outside the home; now over 70 per cent do, and both parents work harder at jobs that are often less secure. Diller suggests that normal children who are simply inattentive or bored with school or who are prone to daydreaming or slow at finishing their chores at home are brought into doctors’ surgeries by hyped-up parents, willingly diagnosed as having a chemical disorder of the brain, and prescribed a powerful drug. The rates of Ritalin prescription vary enormously from one community to the next but are much higher in white middle-class communities, where Ritalin has become a sort of performance-enhancing drug that would be illegal in sport. ‘American psychiatry which used to blame Johnny’s mother for his behavior problems now blames Johnny’s brain.’37 Diller offers a Swiftian ‘modest proposal’: ‘With classroom sizes now averaging about 30 kids per class and about four million children taking Ritalin, I propose we increase the number of children taking Ritalin to seven million and we could probably increase class sizes to 45 children and save a lot of money’.

When doctors reach for their prescription pads they send a series of powerful messages, especially to children. Deviations from the norm, defined increasingly by the imperatives of commerce and the need to secure employment, are medical conditions and the answer is to take drugs to fix them. Trying to understand who you are and how you fit into social structures is a waste of time because the problem is neurological. Reconciling your emotional responses is not something you do through relationships with other human beings and self-understanding; you do it by correcting your faults through outside intervention. As Diller puts it, a ‘living imbalance’ has become a ‘neurochemical imbalance’, and at a time when we are no longer willing to intimidate children into compliance we are willing to drug them into it. It is difficult to avoid the parallel with the Soviet Union’s use of psychiatry as a device for controlling political dissidents.

A society obsessed with ‘making it’—in which the markers of success demand extraordinary commitment to paid employment—has little time to nurture its children with the care they require and deserve. Once a part of the age-old process of reproducing and attaining emotional fulfilment as an adult, children are increasingly expressions of their parents’ preoccupations and abstract desires. Thus they become an encumbrance. The ‘epidemic’ of ADD says more about the changing structure of families, absentee parents, crippling pressure to succeed, a culture of winners and losers, and economies that are ever richer but can devote no more resources to education than it does about brain chemistry. It says more about drug companies’ manipulation of the medical profession and parental demands for instant fixes for children deemed deviant. The ADD craze and Ritalin are making children sick, but society would sooner believe that behavioural problems are caused by neurological disease than confront its own sickness. In this way no one is to blame—not the parents, not the education system, not family structures, not social expectations, not changes in work patterns, and not the pursuit of wealth.

As already discussed, in one of the most systematic statistical analyses of the relationship between self-reported happiness and personal characteristics, the researchers came to a disquieting conclusion: ‘A sense of meaning and purpose is the single attitude most strongly associated with life satisfaction’.38 In contrast with the other factors that have been related to variations in perceived wellbeing—extroversion, goal orientation, personal circumstances such as marriage, and especially income—a focus on a sense of meaning and purpose in life demands a more careful examination of the notion of wellbeing.

The evidence reviewed so far could be criticised for undue empiricism—that is, for being too occupied with measuring happiness and its influences, to the exclusion of a deeper consideration of the nature of wellbeing and the human condition. Philosophers, playwrights and sages have been investigating the fundamental question of human happiness and its determinants for millennia, and they have done so without any recourse to empirical studies other than day-to-day observation of their social milieus. Yet these thinkers have enriched our understanding enormously. The proof of their ideas lies in the ideas’ intuitive plausibility, rather than any validation against the data. In the end, most people will be motivated to accept a new way of thinking about life and social change (such as that advocated in this book) not by the accretion of scientific evidence that contradicts their beliefs but because those beliefs become untenable when confronted by the evidence of their own senses and their understanding of society around them. Despite this recognition of the unimportance of formal empirical evidence, it does remain true in our society that even the most obvious must be backed by dispassionate evidence—if only because those who benefit from denying the obvious will challenge the critic.

Most studies of happiness and its determinants have focused on positive and negative affect (emotions or feelings) and the longer term idea of life satisfaction. In other words, happiness or wellbeing is conceived of as the outcome of events that influence the senses or the self-perceived state. This notion of happiness is generally measured by ‘subjective wellbeing’, based on individuals’ responses to questioning. One implication of thinking of happiness in this way is that it can be consistent with a hedonistic, shallow approach to life, in which questions of values and meaning are reduced to short-term emotional highs and lows. So far, the discussion has been based on the assumption that the objective of humans is to increase their level of happiness and that social organisation and practical politics should be directed towards this aim, or at least to providing the environment in which people can pursue happiness. This premise in itself concedes a great deal to the economic way of thinking and, more broadly, to the thrust of liberal political thought. But this is a modern and rather superficial conception of what it is to be human. Freud used to complain that his American acolytes had interpreted his psychotherapeutic ideas as a technique for making people happy. Steeped in European philosophical tradition, Freud believed this to be a trivialisation of a movement whose purpose was to understand the meaning of what people do and what their behaviour tells us about the human condition. The purpose of life is not to be happy; it is to understand ourselves so that we can achieve personal integration or reconciliation with our selves. It is a process rather than a final state.

Despite his split with Freud, Carl Jung was in accord. For him the purpose of life, and the role of psychotherapy, was to bring the conscious and unconscious minds into harmony and so find wholeness, a process he called ‘individuation’. The approach of Freud and Jung grew out of a much longer tradition, one stretching back to the Greeks. Aristotle discussed happiness using the term eudaimonia. As Carol Ryff observes, the Greeks used daimon to mean genius, and in its original use the word ‘genius’ referred to the spirit assigned to each person at birth to preside over their destiny. Eudaimonia thus means good fortune in life, but Ryff prefers to describe daimon as ‘an ideal in the sense of an excellence, a perfection towards which one strives, and which gives meaning and direction to one’s life’.39 Cast in this light, the pursuit of wellbeing becomes something associated less with day-to-day gratification and more with the evolution of a life, of the potential within each person, and of the ethical principles that underpin right behaviour, an idea that has as much resonance in Buddhist as in Christian thought.

This deeper notion of wellbeing is consistent with psychological theories that identify human lives as the unfolding of potential, notably Maslow’s idea of self-actualisation as well as Jung’s central concept of individuation. From this perspective, stages of life and of maturity become important for self-understanding, and wellbeing becomes identified with positive psychological functioning rather than a snapshot of a person’s emotional state. The question of happiness must be understood in terms of a person’s progress towards self-actualisation, or individuation; that is, approaching a state of psychological maturity in which, among other things, unconscious drives and motivations are being brought to light and made consistent with conscious life goals and principles. From this perspective, happiness is recast as inner contentment—sitting easily with whom one is—rather than a state of more or less positive emotion. The dimensions of psychological wellbeing may be described as ‘self-actualisers’. They include self-acceptance; the ability to maintain warm, trusting and loving relationships; being free of social and cultural pressures to conform in ways that are inconsistent with inner standards; having a clear sense of personal direction and purpose in life; and being in a state of growth and realisation of potential.40

The question arises as to whether this is just a complex way of getting at whatever it is that the simple indicators of life satisfaction measure. This question lends itself to empirical investigation. Ryff ’s study of the meaning of wellbeing indicates that there is a high correlation between measures of generalised self-reported life satisfaction and some dimensions of self-actualisation (notably self-acceptance, environmental mastery and purpose in life) but only a weak association with others (positive relations with other people, autonomy and personal growth). Using the standard measures of wellbeing, women show up as being less happy than men, but using the broader conception of wellbeing provides a more balanced view because women score relatively well on factors such as interpersonal relationships. The research suggests that measures of short-term affective wellbeing may disguise changes in the longer term and a deeper need to realise one’s potential and one’s life purpose. Indeed, as is argued in the next chapter, 20th century consumer capitalism has seen a progressive substitution of activities and desires that result in immediate stimulation for the more challenging and potentially more fulfilling demands of realising one’s potential. There are, then, trade-offs that must be made between short-term gratification and attaining deeper goals of self-realisation, so that it may indeed be necessary to make oneself miserable in order to acquire the understanding needed to become ‘happy’.

This more subtle understanding of wellbeing provides a way into another important but neglected body of research, one that investigates the relationship between happiness and religion. In their overview of this research, Emmons and colleagues observe that religious commitment and participation consistently appear as significant contributors to life satisfaction. However, not all religious commitment is equally valuable, and some forms can be harmful to wellbeing:

At a minimum, critical distinctions need to be made between extrinsic (religion as a means to an end) and intrinsic (religion as a way of life) religiousness, with measures of the former generally showing negative correlations with wellbeing and measures of the latter showing positive correlations with wellbeing.41

Even this distinction—remarkably similar to the secular one made by Kasser and Ryan—fails to reflect the complexity and depth of spirituality since ‘spirituality, as typically defined, encompasses a search for meaning, for unity, for connectedness, for transcendence, for the highest of human potential’.42 This broad conceptualisation of spirituality, which Paul Tillich refers to as an ‘ultimate concern’, has close secular parallels in Jung’s concept of individuation and Maslow’s notion of self-actualisation.

The research affirms that higher forms of spirituality contribute more to contentment than the rituals of church attendance and daily prayer—extrinsic manifestations of religion that may reflect nothing more than a desire for social acceptance, the internalisation of parental expectations, or an insurance policy against the possibility of an afterlife. In a conclusion that suggests that women take their religious beliefs more seriously than men do, the evidence shows that spiritual commitment in women is more likely to be associated with improved wellbeing than it is for men. One of the benefits of spirituality is that it provides an inner landscape within which other, more mundane life goals are embedded. As a consequence, spiritual striving resolves conflicts between other life goals and this conflict resolution makes for more contented souls. In sum, the studies show that spiritual striving contributes more to wellbeing than any other type of goal, including the goals of intimacy, power and symbolic immortality.

Although many people feel uncomfortable discussing spirituality in the context of political and social change—believing that questions of meaning and religion belong in another, more private realm—this compartmentalisation itself is a manifestation of the political and social structure. Consumption and materialism tend to drive out religion, and the more a society emphasises material pursuits and extrinsic motivations as the path to a happy life, the less validity it attaches to the pursuit of meaning or to life’s inner evolution. This is not to suggest that we need government policies designed to increase church attendance. It is to say that modern consumer capitalism’s preoccupation with calculation and a narrow form of rationality is hostile to the acknowledgment and expression of humans’ deeper need for some connection with the mysterious, whether through organised religion or through more personal forms of spirituality. Karl Marx was one of the first to recognise the power of capitalism to change consciousness:

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his ‘natural superiors’, and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment’. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy waters of egotistical calculation.43

Modern capitalism elevates a certain form of rationality to a higher plane. Consumerism and the logic of capitalism are intensely bound up with the rationality of money. As Norman Brown observed, ‘Money reflects and promotes a style of thinking which is abstract, impersonal, objective, and quantitative, that is to say, the style of thinking of modern science—and what could be more rational than that?’.44 The early sociologists and historians of capitalism were struck by the dominance of this new and peculiar form of rationality whose influence spread from market exchange to all forms of social interaction. Like Marx, Max Weber pointed to the irrelevance of all commitments other than self-interest and the depersonalisation of social life. In the world of market relationships the inner worlds of feelings and spirituality were banished from the conscious mind and trivialised to the point where religious affiliation or expression of religious sense attracted derision. In popular culture, spiritual urges and religious convictions are disparaged, and a series of superficial arguments is advanced to prove the irrelevance and futility of religion—it causes more wars than it solves, it’s a crutch for weak people, and so on. All this reflects a deeper transformation, the alienation of self from the seminal urge for meaning and the flight to the triviality of material consumption and frivolous gratification. In the end, religion is seen as ‘uncool’, something that says much more about modern marketing culture than about the relevance of religious striving to the human condition.

The argument here is not that wellbeing should or can be advanced through promotion of religious belief or spiritual endeavour; it is that a society that scorns intrinsic religiousness and trivialises the pursuit of meaning discards thousands of years of insight and can only suffer for it.

Returning to the realm of everyday economics, it is not difficult to show that, even within the framework of market values and humans as consumption machines, the preoccupation with growth can be immiserising. On one hand, our measures of progress show that for decades things have been getting better; on the other, most people complain that society is going to the dogs. Perhaps the problem is that our measures of progress are getting it wrong. Our measure of national progress—growth in GDP or GNP—is bound inseparably to the price system. An activity is taken to contribute to our national wellbeing by virtue of the fact that, and solely to the extent that, it is produced for sale. The defining feature of prosperity has become monetary transaction. This way of measuring national wellbeing omits two large realms: the contributions to wellbeing of family and community and the contribution of the natural environment. Both of these are vital to our wellbeing but, because their contributions lie outside the marketplace, they simply do not count.

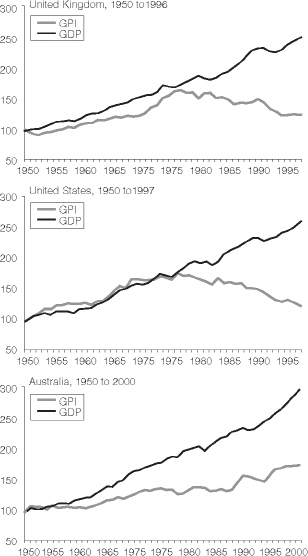

We cannot separate the social afflictions of crime, drug abuse and youth suicide from the societal changes wrought by the market economy. Unemployment, overwork and the pervasive expectation that contentment derives from material acquisition are products of the market system and have profound effects on our welfare. The failure to establish a close relationship between economic growth and improvements in wellbeing, at least above a certain threshold, suggests that the pursuit of growth is occurring at the expense of things that really do increase people’s wellbeing. This has led some to broaden the discussion of the determinants of wellbeing and attempt to build numerical alternatives to GDP as the measure of national progress. One such alternative is the Genuine Progress Indicator, also known as the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare. Using established economic methods, the GPI incorporates a range of factors that influence wellbeing and aggregates them into a single index that can be compared directly over time with GDP. Although there are some conceptual and measurement difficulties with the alternative indicator, its construction points graphically to the glaring inadequacies of GDP as a measure of national progress.

The essential rationale of the GPI is that a measure of national wellbeing that is confined to goods and services produced for the market makes no sense. Many things people ‘consume’ lie outside the market yet affect their wellbeing. As this suggests, the GPI accepts the basic starting point of GDP (and economics more generally) that wellbeing is a function of consumption. This is the GPI’s greatest weakness, but it nevertheless challenges those whose thinking is confined to the consumption model. Within the confines of an economic framework, the GPI attempts to get much closer than GDP to how the growth process is actually experienced by people. It does not include everything that affects wellbeing—or even everything that affects economic wellbeing. Only some aspects that lend themselves to monetary measurement are included. But just adding in a few of the factors that affect people’s daily lives generates a story that is startlingly different from the official one.

The GPI has been constructed for around a dozen OECD countries and usually covers the period from the 1950s to the 1990s.45 It incorporates more than twenty aspects of economic wellbeing that are either ignored or treated incorrectly in the official estimates of GDP. While there are many complex conceptual and measurement questions to be dealt with in compiling the new index, most of it is based on commonsense. An economy growing at 4 per cent but shedding jobs does not leave a community as well off as a similar economy growing at 4 per cent but maintaining employment. An economy that can grow at 4 per cent while minimising pollution is better than one growing at 4 per cent but polluting the air and water. Thus the GPI provides a national balance sheet that includes both the costs and the benefits of economic growth.

What are some of the principal factors included in the GPI?46 When used as a measure of national progress, GDP implicitly assumes that the distribution of income is perfect and that it does not matter whether the richest family or the poorest family receives the extra income economic growth generates. Yet most people would agree that a growing economy contributes more to national wellbeing if poorer households receive a larger share of the new income.47 Although the situation has varied from country to country, one of the general features of the industrialised world in the era of globalisation since the early 1970s has been a worsening of income distribution. The GPI adjusts growth in consumption by a measure of the changing distribution of income.

Much of the work that contributes to wellbeing occurs in the home and the community; examples are caring for children and the elderly, cooking meals, cleaning the house, and coaching the children’s hockey team. Most of this work has traditionally been done by women and continues to be so. Because these activities lie outside the market, their contributions do not appear in the national accounts. Only when the market captures them—as with paid child care, the purchasing of fast food, and the employment of housekeepers—do they appear to add to our wellbeing, because they now have price tags. The GPI includes an estimate of the value of household and community work that falls outside the market.

Unemployment imposes costs on communities and nations well beyond the loss in economic output implied by enforced idleness. Many studies have shown that unemployment leads to a decline in health and skill levels, increased family breakdown and rising crime rates. There are often severe psychological impacts on unemployed people and their families. The GPI includes estimates of the financial costs of unemployment beyond the lost output implicit in the national accounts.

A substantial portion of the spending captured by GDP is defensive in nature; that is, it is undertaken to protect against some decline in wellbeing. For example, if a crime wave (real or imagined) induces increased expenditure on household security and insurance premiums, this spending is recorded as a positive contribution to our wellbeing in the official national accounts. In reality, these defensive expenditures are an attempt to maintain levels of security in the face of a more threatening world. The costs of crime are enormous and include not only the costs of preventing it (through ‘target hardening’) but also the health and repair bills for the victims of it. The GPI deducts from consumption spending crime-related defensive expenditures. Some other types of spending on health and accident repairs are also defensive in character and are deducted to obtain the GPI.

When economic growth causes depletion of stocks of natural resources and a decline in environmental quality, the national accounts either ignore the effects or treat them as a gain. The GPI attempts to assess these costs properly. While GDP counts the value of timber from native forests as a benefit and stops there, the GPI also counts the environmental costs of logging. In the GPI the damage done by greenhouse gas emissions is not ignored (and left as a problem for future generations to deal with); it is counted as a cost of economic activity in the year the gases are released into the atmosphere. The GPI also accounts for the costs of ozone depletion, water pollution, and depletion of nonrenewable resources.

Figure 1 shows the results of GPI studies for the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. Despite the differences in national circumstances, there is a very consistent and startling pattern: while GDP per capita has risen steadily since the 1950s, the more comprehensive measure of national prosperity, GPI, has risen much more slowly and has stagnated or declined since the 1970s. The costs of economic growth appear to have begun to outweigh the benefits. If GDP is used as a measure of national wellbeing, it must be concluded that the citizens of these countries are now much better off than they were in the 1950s and that their condition has continued to improve in each decade. If we take GDP to be a measure of national wellbeing, then young people today appear to be much better off than their parents were. But as soon as we start to add in some of the factors that are excluded from the national accounts a very different story emerges—one that helps to explain the political alienation of recent times. In each of these countries, economic growth appears to be maintained by running down the stocks of industrial capital and infrastructure as well as the stocks of social capital and natural capital, leaving gaping holes in the wealth-creation possibilities of future generations.

Figure 1 GPI and GDP per person: United Kingdom, United States and Australia (1950–2000)

Sources: T. Jackson, N. Marks, J. Ralls and S. Stymne, Sustainable Economic Welfare in the UK: 1950–1996, Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey, 1997; M. Anielski and J. Rowe, The Genuine Progress Indicator—1998 update, Redefining Progress, San Francisco, 1999; C. Hamilton and R. Denniss, Tracking Wellbeing in Australia: the Genuine Progress Indicator 2000, Discussion Paper no. 35, The Australia Institute, Canberra, 2000.

The new indicator is not infallible, or even an especially good measure of changes in national wellbeing, but it does challenge growth fetishism on its own terms. It uses conventional methods to demonstrate some facts that sit uneasily with the official view. The economy draws what it needs from the social realm and the natural world, and only in this way do things acquire prices so that they can be included in the national accounts. The economy spits out what it does not need—redundant workers, toxic wastes—and by this act they no longer appear in the national accounts. Contributions to our wellbeing count only if they are transferred to the market sector; the ‘side effects’ of the market that diminish our wellbeing are sent back to the social and environmental sectors, where they no longer count. The economy values only what it needs; what it does not need has no value.

Defenders of the growth fetish argue that aspects of life outside the economy are distinct and separate and, where they require government intervention, the policy response should not interfere with the activities of the market. But the decline of community and family life and the deterioration of the natural world are not independent of the economy: commerce, the labour market and consumerism are inseparable from their decline. Yet our measure of national wellbeing, GDP, continues to rise. If we look only at the official figures, life should be getting better. It is no longer tenable to maintain that the problems of the world beyond the market can be sliced off for separate treatment. The decline of social life and the environment must be placed at the core of the problem, growth fetishism.