When championship golf courses had no grandstands, spectators came with folding stepladders in order to see over the mass of heads blocking their view. To the U.S. Open at Winged Foot in 1929, a lady in a flapper dress and a wide-brimmed hat brought a bamboo pole and two guys, who held the pole three feet off the ground while she stood on it between them for an unimpeded view of Al Espinosa and Bobby Jones. She kept her balance by placing a hand on each porter’s head.

By 1947, when I was spending the summer caddying in Wisconsin and happened to visit the All-American Open at the Tam O’Shanter Country Club in Niles, Illinois, cardboard periscopes were on sale, and I bought one. Long square columns with angled mirrors, they had become so popular that they gave the compressed galleries an agronomic look, as if they were a growing crop. Through my periscope, I watched Arthur D’Arcy (Bobby) Locke, of South Africa, in his white shoes and plus-fours, tracking long winning putts with his hickory-shafted gooseneck putter. Although I couldn’t actually see him, just his twice-caromed image, he became my instant golfing hero, and he did not disappoint. He went on to win the British Open four times.

I also periscoped Ben Hogan in an early round of the U.S. Open at Merion in 1950, but not long thereafter I abandoned golf in all forms except television, and did not actually go to a tournament until the U.S. Open at Oakmont, in 2007. In the twenty-first century, this is what had become of the periscopes and the stepladders: loaned to the press was a TwitterPod sort of thing called myLeaderboard. It was tied into the United States Golf Association’s central real-time scoring system. You could choose any player in the field and learn what he was doing at any time; you could store certain groups, and the device would follow them. TV screens in countless places—some of them outdoors and in size reminiscent of drive-in movies—gave spectators carrying myLeaderboard the visual assistance necessary for a complete championship experience; myLeaderboard lacked a future, however. Spectators at subsequent U.S. Opens have been commercially encouraged to carry in their hands the four-inch screens of Kangaroo TV, a Canadian company that covers many sports through various on-site feeds and “allows fans attending live events to see and hear all of the action.”

And now, in 2010 at St. Andrews, on the sesquicentennial of the British Open, no one was feeding anything to handheld TV, but neither was the technology of the spectator experience a hundred and fifty years old. For eight pounds sterling, you could buy an “on-course radio” that hung around your neck like a medal while half a dozen commentators described the action through plugs in your ears. On this hallowed Scottish golf course—the Old Course, closely surrounded by five other golf courses—the radio was something like an Acoustiguide in the Victoria and Albert Museum, with the difference that you might not be seeing what you were hearing. While—as described into your ears—a bunker shot beside the fourteenth green made a high tight parabola that stopped within a foot of the flagstick, you would be watching, say, Angel Cabrera driving on the first into the Swilken Burn. “Up and down like an Otis lift!” said Radio Free Fife, whose services were nonetheless valuable.

And pedagogical: “‘British Open’ is an Americanism,” the radio intoned. In Great Britain, yes, it is known simply as the Open, in the way that the Oxford-Cambridge annual eight-oared crew competition is known as the Boat Race, in the way that the apex of American baseball is known as the World Series, and in the way that the revival of Jesus Christ is known as the Resurrection. From Angus to Ayrshire, Fife to Kent, the rota, as it is called, moves currently among nine golf courses. Wars had shut down the championship, and this was actually the hundred-and-thirty-ninth playing of it, the twenty-eighth at St. Andrews, and there was not a lot of dramatic tension in the 2010 Open unless you found it dramatic that a twenty-seven-year-old who had missed three cuts in recent weeks (including the cut at the U.S. Open in Pebble Beach) and ranked fifty-fourth in the world started off as a flash in the pan and then went on flashing and—on the third and fourth days, when he was supposed to go dark—flashed brighter and finished one stroke short of a record set ten years before by Tiger Woods. Leaving far behind the likes of Woods (twenty-third) and Phil Mickelson (forty-eighth), Lodewicus Theodorus Oosthuizen collected a prize of eight hundred and fifty thousand pounds and bought a tractor for his farm in the Western Cape of South Africa, where he was born.

“I won’t talk to them if they call me that.” He answers to Louis now.

After a visit in London, I was joined at St. Andrews before the tournament by Rand Jerris, director of communications and director of the museum and archives of the United States Golf Association, shepherd of the press and post-round interviewer of golfers at U.S. Opens, who had never been to Scotland or seen a British Open. On the evening he arrived, he was so stirred just by being there that we walked the unpopulated course from one end to the other and back in a dense and darkening fog. It is not a long walk—maybe three miles round-trip—because when golf was first played there, on the linksland beside the North Sea, the golfers, speaking Middle English, knocked the ball north to a dunish point over water, then turned around and knocked the ball south on the same path, using the same holes. Grazing animals had eaten away the secondary rough, and there were patches of open sand. The Old Course contains its original self and has evolved at less than Darwinian speed. Jerris is a living textbook of golf and golf-course architecture, and one of the first remarks he made was that he could see Augusta National in that fog. He said that Alister MacKenzie, a Boer War surgeon, English, born in Yorkshire of Scottish parents, had surveyed and mapped the Old Course in the early nineteen-twenties for the Royal and Ancient Golf Club. Having dropped surgery, MacKenzie went on to be a golf-course architect and designed, among many courses in the world, Cypress Point, Royal Melbourne, and Augusta National (with Bobby Jones). In this treeless and littoral terrain, the waters beside it did not suggest to me the Savannah River, but Jerris’s concentration was on the swales, hollows, and longitudinal mounds of the fairways.

I had known Jerris since the nineteen-nineties, when he was a graduate student at Princeton. After Williams College, he had entered the Ph.D. program in geology at Duke, but had become uncomfortable in the Duke curriculum and had eventually landed in Princeton’s Ph.D. program in art history. Recently I asked Lincoln Hollister, a Princeton professor of petrology, how many people he thought could bring off such a move. Hollister said, “One.” Jerris wrote his dissertation on sixth-century to tenth-century churches in the Swiss valley of the Engadine. Absorbed from childhood by golf, he also did an art-history paper on golf courses and the picturesque movement in landscape architecture—golf courses fitting landscapes and not altering them. In Scotland, the natural courses come in three main forms: the linksland courses by the sea, the moorland courses everywhere, and the forested parkland courses of the interior, some involving eskers, drumlins, and lateral moraines, but all the result of various glacial effects. In the United States for almost a century land has been shaped with bulldozers to imitate those forms. After we had walked a mile, a grandstand suddenly materialized in a shroud of fog, a uniformed security guard shivering beside it. He told us to be careful if we meant to continue to the far end. The tee and green signage notwithstanding, we could get turned around and lost.

* * *

WE ALSO WALKED THE COURSE, on the second day of play, with the golf historian David Hamilton, a friend of Jerris’s, who lives in St. Andrews and is a member of the R&A, as the Royal and Ancient Golf Club is known to almost everyone in the world who has ever played enough to break 120 and a scattered few who have not. Rory McIlroy, of Northern Ireland, had shot 63 on the first day, writing his name in golf history beside others’ for the lowest score ever made in a major championship. (Johnny Miller’s 63 at Oakmont in the 1973 U.S. Open stands alone as the lowest-ever final-round score by a champion.) Here at St. Andrews, Louis Oosthuizen had begun this Open with a 65, and John Daly, the low American, with a 66. David Hamilton said of Daly that the Scottish galleries really like him, and that Scottish galleries know what they are looking at and are dead silent in the presence of mediocre golf and will have louder applause for strategic high risk—for a certain shot that ends up fifty feet from the flagstick—than for a shot of lower complexity that ends up eighteen inches from the hole. Scottish galleries take to Daly, Hamilton mused, “perhaps because Presbyterians like a sinner.”

He mentioned certain “Presbyterian features” of the course—the Valley of Sin, the Pulpit bunker, the bunker named Hell—pointing them out as we passed them. St. Andrews’s pot bunkers are nothing like the scalloped sands of other courses. The many dozens of them on the Old Course are small, cylindrical, scarcely wider than a golf swing, and of varying depth—four feet, six feet, but always enough to retain a few strokes. Their faces are vertical, layered, stratigraphic walls of ancestral turf. As you look down a fairway, they suggest the mouths of small caves, or, collectively, the sharp perforations of a kitchen grater. On the sixteenth, he called attention to a pair of them in mid-fairway, only a yard or two apart, with a mound between them that suggested cartilage. The name of this hazard is the Principal’s Nose. Hamilton told a joke about a local man playing the course, who suffered a seizure at the Principal’s Nose. His playing partner called 999, the U.K. version of 911, and was soon speaking with a person in Bangalore. The playing partner reported the seizure and said that the victim was at the Principal’s Nose bunker on the sixteenth hole on the Old Course at St. Andrews, in Scotland; and Bangalore asked, “Which nostril?”

As the Old Course expanded in the nineteenth century from a single track to a closely paralleled double track, seven of the new pairs of fairways ended in common greens, as they do today. These double greens, each sporting two flagsticks, are even weirder than the pot bunkers. Their cardinal feature is immensity. Putts on them are sometimes described in yards rather than feet. An approach shot blown off course can result in a putt with fifty yards to the hole. Standing beside the expanse shared by the fifth and thirteenth flags, David Hamilton said it was the largest. American football teams could play an exhibition game on this green.

While the greens are outsize, the Old Course, as a unit, is much the opposite. Championship golf courses in the United States typically occupy about a hundred and sixty acres. This ancient links course, with its contiguous fairways and longitudinal economy, fits into a hundred and twenty. It is like a printed circuit with its sibling courses on a linksland peninsula between the estuary of the River Eden and the North Sea. When I was twelve years old, I was so naïve that I thought golf links must be called that because the game was played on a sort of chain of consecutive holes. Jimmy Kahny, also in the eighth grade, introduced me to the term as a result of my telling him that I needed money so I could buy an all-weather basketball and dribble my way to school. He said, “There’s good money at the golf links, caddying.” The good money was one dollar for toting two players’ bags, a service known as doubles eighteen. I got my basketball, but—in those caddying seasons—no hint that links were called links before golf was played. The word comes from Old English and refers to a coastal topography behind a beach, a somewhat dunal and undulating landscape, untillable, under bushes of prickly gorse, scattered heather, and a thin turf of marram and other grasses. Scotland is necklaced by these essentially treeless linkslands, brought up from the deep by the crustal rebounding of a region once depressed by glacial ice, links about as vulnerable to sea surges as Los Angeles is to earthquakes, common grazings good for little else but the invention of public games, where marine whirlwinds could blow out the turf and create ancestral bunkers—for example, Turnberry, Muirfield, Dornoch, Crail, Carnoustie, Prestwick, Royal Troon. Carnoustie, to the north of St. Andrews, was just past the Firth of Tay. “If you can’t see Carnoustie, it’s raining,” David Hamilton said. “If you can see Carnoustie, it’s going to rain.” We could not see Carnoustie. David Hamilton—in moccasins, cotton trousers, a blue shirt, a maroon tie, a beige sweater-vest, and a billed cap that said “The Old Course, St. Andrews Links”—seemed unaware of rain, as befitted the author of Golf—Scotland’s Game (Partick Press, 1998), an attractively written definitive history, amply and informatively illustrated.

Golf links are wherever you call them that. There’s a difference between golf links and links golf. Linksland is where links golf is played. It differs substantially from landlocked, parkland, A to B to C to D golf in this way, among others: it is less linear, and there is greater freedom to select a line from tee to green. For example, on the Old Course players can aim anywhere on the mated fairways. Tiger Woods goes off the first tee to a strategic lie on the eighteenth fairway. Players we watched on the sixteenth were driving up the third to avoid the Principal’s Nose. Never mind the occasional high hedgerows of impenetrable gorse, the rippling hay, the patches of heather; most of this wide and treeless panoramic savannah is a carpet of smooth grass; you could all but use a putter from tee to green. It looks easy until you see John Daly hunting for his ball on the third fairway, which, typifying a links fairway, has the loved-in texture of a rumpled sheet. A ball lost in a fairway! A player has five minutes to locate a lost ball, and Daly and his entourage need it. The third fairway, like nearly every other Old Course fairway, has the pit-and-mound topography of a virgin forest, but it wasn’t made by trees.

Golf-course architecture has tried to imitate linksland in some most unlikely places (Pennsylvania’s Oakmont, on the Appalachian Plateau; California’s so-called Pebble Beach Golf Links, on Salinian granite) and to create parkland so universally that countless acres of artificial biosphere have to be sustained on mined water and synthetic chemicals. Rand Jerris remarked that the U.S.G.A. has embarked on a crusade of “sustainability—more sustainable turf grass, use of less water. The ideal of the lush green course is not so ideal anymore. There’s a trend toward minimalism in golf-course architecture. Courses by Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw, for example, move as little dirt as possible.” Resonating as this does with the origins of the game itself, golf might do well to get rid of the lush and plush, and go back to the lyrical imprecision of playing over natural country, as the first golfers did on the Old Course, teeing up on wee pyramids of sand and whacking the ball past the sheep toward holes that grew larger by the end of the day. For six hundred years—let alone the Open’s hundred and fifty celebrated this summer—golfers on the Old Course have not been able to see where they are going. Links courses generally are described in the sport as blind—all those dunes and mounds hiding greens from tees and fairways. Going out—away from the university town—the golfers and their caddies use an experiential form of dead reckoning. Turning around, they see a skyline of cathedral spires, crenellated battlements, church steeples, and bell towers, and they use them to avoid the invisible bunkers and find the hidden flagsticks on the inward nine.

To one extent or another, an architect can make a simulacrum of all of the above, but what nobody can imitate—you’ve either got it or you haven’t—is wind. Jerris said, “This is not target golf, but more a matter of strategy, choosing your route, so many blind shots. The more you play links golf, the more you understand the subtleties. It takes a lifetime to learn it. Its defense is the wind.” Yesterday, a near absence of wind was the main reason so many golfers scored exceptionally low in Round 1 of this 2010 Open. In the eerie calm and after a night of heavy rain, well-aimed shots would stick like darts in cork. Oosthuizen, his saga scarcely begun, was already seven under par—hitting good, loose shots with his technically flawless swing. Among the A.M. threesomes the average score was 71. The average in the afternoon was 73. The difference was a rising but nonetheless substandard wind.

Now, before Round 2 was half over, winds that had been gusting at thirty miles an hour started running thirty in low gear, gusting to forty and fifty. People in the galleries, ignoring rain, were tilting umbrellas ninety degrees to fend off the wind. In grandstands, they wore umbrellas on their backs like capes. The weather made Jerris happy. He called it “true links conditions.” Lorne Rubenstein, of the Toronto Globe and Mail, the author of This Round’s on Me, once wrote, “The surprise is that so few players, professionals and amateurs, really get it when it comes to playing links golf.” His remark embraced the geometric strategies and all the additional aspects of golf-ball navigation on this trackless green ocean, but it mainly meant coping with the wind. And who might those few players be who really got it? Rubenstein: “Nicklaus, and now Woods, grasp links golf.” If the book goes into another printing, he could be adding Oosthuizen, of whom the English golfer Lee Westwood has said, “He flights the ball very well when it gets windy. Has good penetration on his iron shots, and he has obviously got a lot of bottle.” “Bottle” is English for unflappable demeanor and nerves of steel. According to Jerris, Tom Watson, who grew up in Kansas City, is “a master” in wind, and golfers from Texas have tended to be wind masters, too—Ben Hogan, Ben Crenshaw, Byron Nelson. “They’re good at reading the wind, and at the interaction between wind and topography. A crosswind can put a ball thirty to forty yards off line. Downwind can be even more difficult. Downwind takes spin off the ball. Links golf is more of a ground game than an aerial game like parkland golf. A ball hit lined up with your rear foot has a lower trajectory. The lower they go, the more penetrating the shot is. If they bounce and roll, wind has less effect. If you want to go right or left with the wind, you don’t just leave it to the wind; you apply a fade or a draw, too. Hit a draw up into the wind—a shot that bores into the wind. It’s like tacking. You can tack in three dimensions—distance, trajectory, direction.” Links golf has more than a little in common with regatta sailing. Close hauled. Running before the wind. Jibing over. Luffing. Coming about, hard alee. In irons.

Phil Mickelson, the 2010 Masters champion, understands links golf perhaps better than he plays it. It is just a matter of “taking more club and swinging easier,” he said in a pre-Open press interview. He finished tied for forty-eighth. Easy doesn’t always do it. Against a stiff wind, you might have to punch hard—a shorter backswing, a shorter follow-through, delofting your club for a lower flight. On the seventh at Pebble Beach, a very short par 3, players have hit 5-irons that would splash in the Pacific if the wind did not blow the ball back. They use, in other words, a hundred-and-ninety-yard club for a hundred-and-ten-yard hole.

Radio Free Fife: “How many pins have the players aimed at this week?”

“Dead aim?”

“Yes.”

“None.”

Where on earth are these guys?

Jerris: “In a trailer somewhere on the course, monitoring their feeds.”

Wind affects putts, too—crosswinds blow them off line, gusts from behind can fatally accelerate a roll downhill. Westwood again: “Everybody thinks when the wind blows it affects the long game most, but it doesn’t. It tends to affect the putting the most. The putter is getting blown all over the place, and the ball gets hit by the wind.” When the force of the wind reaches forty miles an hour and more, balls that have come to rest on greens may move on their own. The wind putts them. More often the motion is no more than an oscillation. A golfer prepares to putt, and his ball wobbles back and forth as if the earth beneath it were quaking. When balls move on greens, play is suspended, and the several dozen playing players leave the course, to return to their exact positions at some unpredictable time. In this second round of the Open, play was suspended for sixty-five minutes in the early afternoon, but Jerris and I and David Hamilton had already suspended ourselves and were lunching in St. Rule, one of the two women’s golf clubs that play on the Old Course.

* * *

ST. RULE is on the public street beside the eighteenth green and fairway—on one side, two hundred and fifty yards of contiguous shops, the houses of clubs like St. Rule, and private homes. Unpaying galleries collect on the street to watch golfers finishing their rounds and others, beyond them, hitting off the first tee. This inboard extremity of the Old Course is a world-class cliché in golfing scenes, likely to be on calendars in McMurdo Sound, which makes it no less impressive—the double fairway three hundred and eighty feet wide, the university buildings, and the Royal and Ancient clubhouse like a monopoly token made over time by six architects working in six idioms and finding the offspring of a moated Highland villa and a Florentine castle.

From upstairs bay windows, ladies of St. Rule are watching, too, decorously yielding the view to one another, while members of the St. Andrews Golf Club, all male and in their own bay window a few doors along the fairway, are marginally less yielding. The golf course under these windows belongs to the town and not to any of the golfing clubs, including the Royal and Ancient one. In Scotland, there are relatively few private courses, and few golfing clubs with clubhouses, but every factory, church, hospital, bank, and insurance company has a golf club without a course, and pays green fees at municipal courses. Among the thousands of “club without clubhouse” golfing societies was the one David Hamilton’s father—a “minister of religion”—belonged to in Glasgow. Ministers’ Monday consisted wholly of clergy who met on Mondays where “they could talk golf and swear.” The name of David’s wife, Jean Hamilton—a slender, supple athlete with quick dark eyes—was up on a wall of St. Rule as a champion, as were, for example, “Lady Baird-Hay, 1896,” and “Lady Anstruther, 1898.” Also, Jean belongs to St. Regulus, and she explained the difference: “St. Rule is a ladies’ club with a golfing component; St. Regulus members are scratch golfers.” Offhandedly, her husband added, “The ladies’ clubs are not clamoring for male members.”

The University of St. Andrews, brooding above those terminal fairways, is led by a principal whose accession to office has traditionally been accompanied by an automatic membership in the Royal and Ancient Golf Club. In 2009, Louise Richardson became the principal of the University of St. Andrews, the first of her gender, and to date she is not a member of the R&A. David Hamilton kindly showed us through the place, with its varieties of panelled hardwood and its central social Big Room full of deep-leather comfort and—through multipaned windows—a floor-to-ceiling view of the course. In a philosophically Scottish manner, the Big Room doubles as a locker room. Actual panelled-wood lockers line the walls. The place is a form of nude bar, a sanctuary for the nude member. The professional golfers are said to dress in an R&A basement locker room, but they don’t. After their rounds, they leave in spikes and go back to their hotels and bed-and-breakfasts. Phil Mickelson leaves in spikes. Louise Richardson does not even arrive in spikes. Born in Ireland, she is a Harvard Ph.D. who was also a Harvard professor before her move to St. Andrews. Her field is political science, and her expertise is in, among other things, terrorism. She plays about as much golf as the Statue of Liberty does. But a tradition is a tradition, an honor can be honorific, and a principle is a principle is a principal.

In real-property terms, the R&A is just an ungainly house on a fragment of an acre between the university and the municipal golf courses, but the R&A is source, arbiter, and guardian of most of the rules of golf, keeper of the political science of golf, and it could use some help. For nearly sixty years, it has shared its world hegemony with the United States Golf Association. No major rule on either side has differed since the R&A gave up the small ball, in 1990. It was about 3.6 per cent smaller than the American ball, and behaved like a bullet in the wind.

Of the three alpha-level all-male clubs in St. Andrews, the two others are the New Golf Club and the St. Andrews Golf Club. Not to put too fine an edge on it, there is class stratigraphy in these organizations. Read up from the St. Andrews Golf Club, which, in a local vulgate, is called the Artisans. Jack Nicklaus is an honorary member. The New Club embraces the middle class. The R&A is a club of “gentlemen.” It has two thousand four hundred members, that fine an edge.

We looked in at the Artisans, a four-story hubbub of men holding pints. At the bottom of its atrial stairwell, a sign on the newel post said, “Members are reminded that the Snooker Room is closed until 19 July.” David Hamilton said he was a member of the Artisans as well as of the R&A, and he described the Artisans as most populous on Thursdays, because it is the club of shopkeepers, and shopkeepers historically have been busy on Saturdays and off on Thursday afternoons.

I said, incredulously, “You’re a shopkeeper?”

He said, “I have a printing shop.”

Off we went for coffee and to see his printing shop at his house on North Street in the middle of town. In a stone shed between house and garden were two hot-metal presses, gleaming with mechanical health in a cluttered space more suitable for potting. In racks overhead were upwards of fifty hickory-shafted golf clubs. This was Partick Press, where he prints what he calls his “short, arcane things.” For example? “A poem on student golf.” When Partick published Golf—Scotland’s Game, in 1998, it was printed in Edinburgh. “All the various studies were headed toward a big book,” he said. “I wanted complete control, so I published it myself.”

Most people in David Hamilton’s profession prefer complete control. He was teaching medicine at Oxford in the nineteen-eighties when he followed an avocational interest and “took instruction in letterpress.” He and Jean had little money, and to finance this two-year “sabbatical” from his work in Glasgow they went for a fortnight every couple of months to Baghdad, where he performed kidney transplants for Iraqis. In the United Kingdom, he was an early practitioner of organ-transplant surgery, the author of classic papers in medical journals. He has written a book called A History of Organ Transplantation (2012). His other books include The Healers: A History of Medicine in Scotland (1981) and The Monkey Gland Affair (1986), which cast something heavier than heavy doubt on the claims of a Russian surgeon to have restored erectile function in humans by implanting tissue from the testicles of monkeys.

Remarking on his years in Oxford, he said, “It was a midlife escapade. They regarded me as an amiable eccentric.” He was a six-handicap golfer, and back in Glasgow he became an occasional champion of the Western Infirmary Golf Club. Retired from surgery since 2004, he teaches each year about a hundred and fifty future doctors as a lecturer in medicine at the University of St. Andrews.

I asked, “Are they all undergraduates?”

“We say ‘students’ in Scotland,” he replied. “They say ‘undergraduates’ in England.”

On the way to his house, we had passed a university door on which block lettering said in gold: “STUDENT EXPERIENCE OFFICE.”

We had dinner at the New Golf Club with David and Jean Hamilton as guests of their friends and neighbors David and Ruth Malcolm. A St. Andrews native with auld Scotland in his ruddy face and pure Fife in his lilting voice, David Malcolm is the co-author (with Peter E. Crabtree) of Tom Morris of St. Andrews: The Colossus of Golf 1821–1908 (2008). The book is not only a biography of the caddie-player-greenkeeper-clubmaker who was the sport’s most famous figure in the nineteenth century but also, as wider history, the peer of David Hamilton’s Golf—Scotland’s Game. There is a society in St. Andrews called the Literati of the Links whose members meet now and again to talk golf history and discuss one another’s monographs. The two Davids are Literati. At Prestwick, in Ayrshire, Tom Morris won four Opens. Tiger Woods has won three. Tom Morris became Old Tom Morris after his son Tom Morris won four more. In a hundred and fifty years, twenty-two Scottish golfers have won the Open—three since the First World War. This nostalgic macaroon is more than enough to set David Hamilton onto what he calls “the golfing diaspora” of Scottish professional golfers, immigrating a century ago to the United States and Canada. In his words, “It was a black hole in professional golf in Britain. The sudden decline in Open champions was because young men were leaving Scotland in huge numbers. In Scotland, they were working class, treated as inferiors. Working-class kids from Carnoustie and St. Andrews would be immediately pigeonholed in England, but not in North America. In America, they may have been gruff and taciturn, but they were classy.” The Morrises remained autochthonous. In 1902, Old Tom Morris helped found the New Golf Club, on the third floor of which we were dining by windows overlooking the Old Course. In 1908, Old Tom fell down the New Club stairway and did not survive.

Play had resumed, but the wind had not much subsided. If the MetLife blimp were to take off here and now, it would soon be in Yorkshire. Blimps and Scotland are contradictions in terms. The BBC looks down on the golfers from Guinness-record cherry pickers. Even our own altitude, in the New Golf Club dining room, was enough to make particularly evident the contrast between the two sides of the planet’s widest fairway. Below us, the eighteenth-hole side was wrinkled with mounds and deep hollows, including the Valley of Sin—the depressed apron of the eighteenth green, something like a large deep bunker full of sod. The eighteenth side, like nearly all of the Old Course, was an image of its former self—ancestral linksland topography. Beyond the eighteenth and down the eastern side—below the first tee—was a sweep of ground unnaturally smooth. David Malcolm explained that it was “reclaimed” land. Hulls of old herring boats, loaded up with rock, had been positioned there to anchor new ground filled in around them. The project had also roofed a sewer, he said, that ran out from the town. When the sewer flooded, armies of large rats ran into the R&A.

After dinner, in the all but endless summer daylight, Jerris and I return to the course, and to the wind-chilled grandstand over the seventeenth tee, one of three fixed positions from which we have decided to watch things from day to day unfold, another being above the seventeenth green. In the defenseless calm of the first round, as various players have remarked, all but one hole was easy; the seventeenth was, as ever, “impossible.” A dogleg par 4 newly stretched to four hundred and ninety-five yards, it presents an arresting scenario. The tee shot is completely blind and eliminates the bend by going over a large, elongate shed. The golfers confront its north-facing wall and aim across a sign above which nothing is visible but sky. The sign says:

OLD COURSE HOTEL

St. Andrews

Golf Resort & Spa

The shed is a part of the grand hotel, and close on the right are a great many guest-room windows. To the left of the sign is a lion rampant. A pusillanimous shot is a drive hit over the lion rampant. Wind heavily influences the selection of vector, but, generally speaking, a reasonable choice is over the “O” in OLD, and there is high risk and big money in the “O” in HOTEL.

The fairway is scarcely fifteen yards wide at its narrowest. In Jerris’s words, “You are hitting over out of bounds to a fairway you can’t see. The fairway is a right-hand dogleg fade, but if you fade it too much”—as you influence the ball to curl to the right—“you are back on the tee hitting 3.” Psychologically unbalanced by this possibility, golfers “get quick,” roll their hands as they swing, close the club face, and send the ball into too big a draw to the left and into hay that is less suitable for rough than for harvest. Brute strength is needed to get out and reach the green. After Angel Cabrera hits his second shot to some other destination, hay is hanging from his follow-through like Spanish moss. The longest successful drive we see on seventeen is by the American sinner John Daly, wearing slacks meant to resemble the skin of a red-and-black tiger. Daly won the Open at St. Andrews in 1995, ballooned in weight in subsequent years, did some rehab, and now has an implanted turnbuckle around the upper end of his stomach, like a great cormorant on the Yangtze River.

Because an asphalt thoroughfare runs beside the green and some of the fairway, the seventeenth is known as the Road Hole. Small and narrow and shaped like a kidney, the green is one of the four on the Old Course that have only one flagstick. The celebrated Road Hole bunker—straight-walled, cylindrical, five feet deep—fits so snugly into the kidney’s indentation that it can virtually be regarded as a bunker in the middle of a green. From the grandstand above the green, the wider view right to left a hundred and eighty degrees is of the crowds on the public street, the eighteenth green, the university, the R&A clubhouse, the media’s big white tent, the North Sea rolling toward the beach where the British runners ran in the film classic Chariots of Fire, the coast across the water on its way to Dundee, and the shed that makes this hole the blindest on the course. Players on the tee are as invisible to us as we are to them, so we don’t see them hitting. Balls just appear on the fairway, seemingly out of nowhere, or they disappear elsewhere, while we stare at the old shed in anticipation of the players who will come around it next, like scouts coming over a ridge.

A yellow golf ball appears. I ask Jerris whose it might be.

“Hirofumi Miyase’s,” he says.

“And how do you know that?”

“Because he’s playing with Steven Tiley, and there’s no way an Englishman is going to use a yellow ball.”

This is the third round now, and the flag is out straight in the stiff wind. Henrik Stenson, seven under coming into seventeen and tied for the best score of the day, gets into the Road Hole bunker, is compelled by his lie to come out in an ersatz direction, and is no longer tied for the best score of the day. The pin is positioned close to the road, with short steep rough and a cinder path between, and a few feet behind the road is a stone wall that would not look amiss in New England. Watching bogey after double bogey, we see errant balls bump-and-running beside the green and going up against the wall, or bouncing on the asphalt and over the wall. “The wall on seventeen is an immovable obstruction from which you don’t get relief,” Jerris says. “It is not a T.I.O.—a temporary immovable obstruction, like a TV tower or a grandstand. At this stone wall, there’s no relief.”

Comes Mickelson and he is over the road and close to the wall with room barely for a short swing. He smacks a great shot against the short, steep greenside rough; the ball pops up, continues, and comes to rest near the hole. In Southern California, behind the house he grew up in, Mickelson’s parents installed a golf green with a short-game practice area in the way that other people install swimming pools. But he misses this putt and is down in bogey five. Miguel Ángel Jiménez will soon appear, and go so close to the wall that he has no open swing whatever, so he punches the shot straight into the stone wall, and it ends up behind him on the green.

Most of the entourages walking with the golfers and caddies number about twelve—marshals, scorer, standard bearer, R&A rules official, forward observer, and so forth. Woods and Darren Clarke come around the shed with an entourage two and a half times the usual size, starting with extra marshals. Clarke is out of bounds by the hotel. Woods is in the hay. He blasts out, goes into more hay. His third shot ignores the green. It crosses the cinder path, crosses the asphalt road, and stops a club length from the stone wall. Woods conjures a high parabola that sits down close to the hole. Jerris calls it “the ultimate cut shot, a parachute shot.” It saves a bogey, but not a major.

Comes Rory McIlroy around the shed, and his second shot is so close to the stone wall that he can only hit his next one away from the green. In the wild winds of the second round, the Old Course rebuked him with an 80. Now he takes a double bogey—on his way, however, to a 69.

A time comes when the groups that like clockwork appear around the shed have stopped appearing like clockwork around the shed. The spectators in the grandstand by the green stare at the shed as if to make things happen, but nothing happens; the shed seems to have more past than future. As if the seventeenth, across time, had not developed within and around itself enough unusual hazards, a railroad ran up it until fifty years ago and was not out of bounds. The shed had been built for storing coal and curing golf-club hickory, which the trains dropped off. Only golfers are overdue now.

Vijay Singh appears around the shed. The Big Fijian is deliberate. Read: slow. He takes his time, and yours. He has also taken home as much as ten million dollars in a year. He is a Masters champion and a P.G.A. champion (twice), and has won the FedEx Cup—a résumé that has not made him overly selective about where he plays. He is as professional as it is possible to be, signing on for more tournaments worldwide than almost anyone. Golf pays well, and Singh may take his time but he is on hand to be paid. Even with his easygoing liquid swing, he bogeys the hole.

From this same grandstand perch, the eighteenth tee and the great home fairway are right in front of us as well, where the Swilken Burn, straight-sided and in cross section no less engineered than the Los Angeles River, leaves town in ampersand fashion on its leisurely way, across the eighteenth and the first, to the sea. Player after player, released from the seventeenth, explodes up the final fairway—par 4, three hundred and fifty yards—and lots of them drive the green. Birdies gather. And while the guys on eighteen go up the killing ground, Louis Oosthuizen and Mark Calcavecchia, playing in our direction, hit off from the first tee, each about to bogey. They are the last twosome—No. 1 and No. 2 halfway through the championship—but Calcavecchia will disintegrate today, taking nine strokes on the fifth and finishing in 77. Not so Oosthuizen, who is expected to crack but will not. Seeming less tense than a length of string, he walks down the first, his caddie beside him.

Oosthuizen’s caddie is a black South African nearly twice his age—one of few black caddies on the European tour. His name is Zack Rasego. He lives in Soweto, has worked for Oosthuizen for seven years, and was once Gary Player’s caddie. Frustrated by missing so many cuts in recent weeks, Oosthuizen decided that he needed a fresh caddie, and so he told Zack Rasego that after the Open the two of them would be parting ways.

* * *

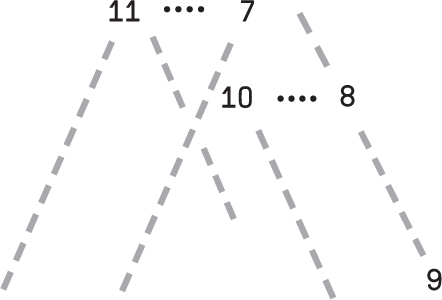

AT THE ANCIENT TRACK’S REMOTE END—where the Old Course makes the turn—are five tees, five flagsticks, and three greens, collectively known as the Loop:

It is a sequence of holes so hallowed in the game that Amen Corner, at Augusta National, has been compared with it, but while the Loop is far more complex geometrically, as golf goes it is less difficult. Birdies are to be made, just lying there for the taking, unless the wind is blowing hard, which it nearly always is. This prow of the linksland is much like the bow of a ship in the winter North Atlantic.

In the experience of David Fay, the executive director of the United States Golf Association, the grandstand above the 10-8 green in the Loop, which also looks over the crisscrossing fairways that lead to 11-7, has “the best view in all of sports.” He may not have consulted with Spike Lee. He may have avoided Jack Nicholson. Nonetheless, the place is breathless in every meaning of the word, as the cold wind bends the simplest of shots and penetrates every layer of every fabric armed against it. If you are in the top row and the wind is coming over your back, seagulls hang motionless and stare into your eyes, a club length from your face. It’s a Brueghelian scene against the North Sea, with golfers everywhere across the canvas—putting here, driving there, chipping and blasting in syncopation, but being too smart to loft a wedge lest the ball be blown to the streets of St. Andrews a mile and a half away. When we turn around, the rest of the course is visible, all the way back to the masonry of the medieval town: golfers and galleries stopping and moving, moving and stopping—it’s like watching a Swiss astronomical clock reacting to the arrival of noon. The dark marching lines of the galleries cross fairways in hooded parkas, in rain pants—serious, this. They are much grayer, these Scottish cognoscenti, than, say, a gallery in California. They are mainly from Edinburgh and Glasgow, in addition to the locals from Fife, and they appear to be of an age with the parents and grandparents of American galleries.

As course design, the X point in the Loop, where the eleventh and seventh fairways cross, may have been thought out by the same ram and ewe that caused West Fourth Street to wander all over Greenwich Village and eventually intersect West Twelfth. Jerris remarks that when Bobby Jones played through the Loop in his first Open, in 1921, he hit across the X, went into a bunker, came out ripping up his scorecard, and walked off the course. In 1958, he was made a freeman of the Town of St. Andrews—the first American so honored since Benjamin Franklin.

Morning on the Loop, Round 4, and a chill wind is blowing.

On-course radio: “There really isn’t any wind to think about now.”

Jerris: “Not in their trailer.”

Vijay Singh makes the turn, strolling around the Loop. Think sixty minutes to go through a revolving door.

Ryo Ishikawa, three under par, hits to fifteen feet on the tenth, and holes the putt. He is eighteen years old. A few months ago, in a tournament on the Japan Golf Tour, he shot a 58. From St. Andrews, tied for twenty-seventh, he will take home four million yen. For thirteen years, the bright aura of Tiger Woods put the field behind him into relative twilight. Woods was like a screen saver, or some sort of curtain or scrim, veiling what else might be seen. Now and again, directors clicked on Phil Mickelson and others, but the focus of narrative attention was Tiger Woods, cameras buzzing his every stroke like horseflies. Now that the scrim has been removed, not the least of the dividends is the montage of young and outstanding golfers—like Ishikawa, like Oosthuizen—going by. The German Martin Kaymer, twenty-five, will gross $186,239 in a tie for seventh, as will the Americans Sean O’Hair, twenty-eight, and Nick Watney, twenty-nine. Rory McIlroy will tie for third despite his 80 in the second round, and he will collect $394,237. Before the 80, McIlroy had played nine rounds of tournament golf on the Old Course at St. Andrews, among which his worst score was 69. In May, at Quail Hollow, in Charlotte, he shot a final-round 62 to win $1,170,000 and beat Phil Mickelson by four strokes. Five years ago at Royal Portrush in Northern Ireland, where the Open was once played, McIlroy shot a 61 and set the course record. He was sixteen years old. And Rickie Fowler, aged twenty-one, comes into the Loop dressed in hunter orange, blaze “orange from head to toe—shoes, pants, belt, shirt, hat, bracelet, necklace, it’s my school colors, I went to Oklahoma State!” Radio Free Fife says he “looks like a prisoner.” So far this year, Fowler’s first full year on the tour, he has twice finished second and has won more than two million dollars. He will add $87,839 today, as he ties for fourteenth, like South Carolina’s Dustin Johnson, aged twenty-six, and the Korean Jin Jeong, twenty; but Jeong will get nothing—he’s an amateur.

Out in the Open are old guys, too. Here John Daly comes into the Loop with an entourage of twenty-one people. Daly’s habiliments change daily. He now has stars on his right leg and stripes down his left leg—red, white, and blue. Red jacket. White cap. When Ian Poulter, of Buckinghamshire, appeared in clothes derived from the Union Jack, it was said that he looked as if he were about to be buried at sea. Jerris says Daly is dressed for a Princeton reunion, but I would put him in any town’s parade on the Fourth of July. He shot a 66 in the first round. He is now one over for the Open. On the seventh, he hits an iron off the tee to lay up short of a bunker, then a dare-the-wind wedge to twenty feet past the hole, then a lagged putt and in for a par. The grandstand is wild for him. “He plays fast,” Jerris says. “Scots like that. They play faster than we do.” After Daly drives off the eleventh tee and nears the end of the Loop, there’s a mass exodus from the grandstand.

* * *

IN THE AFTERNOON, Jerris and I split up—he to stay on the course, I to go into the Media Centre. After Tiger Woods scored 67 in the first round and went to the Media Centre for a press interview, the crush of spectators outside the tent was so heavy that hundreds were gridlocked on foot, compressed, unable to move. A Scottish voice in the crunch asked, “And what did he end up shooting?” To which a Scottish voice replied: “His missus.” To the extent that there is any crush outside the tent now, it is caused by the media crowding in to watch the climactic holes of the 2010 Open on the BBC feed.

The Media Centre is sixty yards long and thirty yards wide, or enough to provide desk space, Internet access, and free food to five hundred journalists—not to mention swiftly distributed transcriptions of all player interviews, the common source for essentially every line of dialogue that goes out into the print world. The atmosphere is less bookish than bookie-ish. Along one side is a full-field scoreboard that resembles a tote board in an off-track betting parlor. It is not electronic, though. Its many numbers are changed by hand by women on sliding ladders. At either end is the BBC—golfers in action on silent screens about the size of sheets of plywood. Heavy rain on the tent roof can be so loud that nobody would hear the audio anyway. It helps to have an on-course radio around your neck. My assigned space is between Peter Stone, of The Sydney Morning Herald, and Brian Viner, of The Independent. In our immediate surroundings are The Detroit News, the Tokyo Shimbun, The Augusta Chronicle, The Charlotte Observer, the Golf Press Association, Desert Golf Magazine, and a line of laptops from the Associated Press. As the Open nears its end, more people are in here than have been in here at any other time all week. When those British runners in Chariots of Fire came off the beach and jumped a fence and headed toward the first tee, they ran right through the Media Centre, in a manner of speaking.

Stewart Cink, the defending champion, finishes the eighteenth one over par. Tied for forty-eighth, he will barely make it home to Georgia with $21,130. After a three-hundred-and-fifty-six-yard drive that stops two feet from the flagstick, Tom Lehman eagles the eighteenth ($87,839). Meanwhile, the on-course radio is impressed enough with Louis Oosthuizen to jinx him into the Valley of Sin, the Principal’s Nose, and the Swilken Burn. He is “totally relaxed,” “looks unstoppable,” “looks very solid indeed,” and has it “just the way he wants it to be—a one-horse race.”

Gradually, as I listen to the radio and watch the tote board and the television images, dawn cracks and I come to realize that the BBC is the only feed that the on-course radio commentators have. They are not out there, as imagined, rolling around in some mobile home with windscreen wipers and video-cam monitors. Like all the other journalists in five or six media, they are doing their reporting from inside this tent.

Paul Casey, who is English and almost thirty-three, is with Oosthuizen in the final pairing, having begun the day eleven under and four strokes behind. If the Open championship is to result in any kind of duel, most likely it will happen here. But while they match each other hole for hole, they walk along chattering, joking, laughing, failing to act as if a drive here or a chip there could be worth more than a few hundred thousand pounds. My pendant radio says to me, “It’s all going to start to happen down in the Loop.”

Down in the Loop, Oosthuizen bogeys the eighth while Casey makes par. Grandstand and gallery, the crowd waxes partisan with a Great British roar. It seems loud enough to crack concrete, but perhaps not loud enough to crack Oosthuizen. Casey, with the honor, now drives the ninth green—three hundred and fifty-seven yards—again detonating the crowd. Oosthuizen looks down steadily at his glove, now tees up, drives, and also reaches the green, but closer to the flagstick and on a better line. Casey putts for eagle. Misses. Oosthuizen putts for eagle and the ball rolls in. There is a red spot on Oosthuizen’s glove. He put it there to help him concentrate. He continually glances at it as if it were a coach.

Again chattering and joking, Oosthuizen and Casey come to the twelfth hole, where Oosthuizen’s drive carries five mid-fairway bunkers and rolls out between islands of gorse, leaving only a short pitch to the green. There is an aggregate acre of gorse. Casey goes into it. R&A marshals plunge into the bushes, searching—a brave thing to do among the concertina spines. Playing yesterday with Oosthuizen, Mark Calcavecchia also went into gorse. He played a provisional ball, but after he was told that his ball had been found he picked up the provisional and went to play the found ball. It wasn’t his. Penalized stroke-and-distance for the lost ball and another stroke for lifting the provisional ball, he ended up with a 9, and it was ciao, Calcavecchia. Now, standing idle in the cold wind during the search for Casey’s ball, Oosthuizen pulls on a sweater. If nothing else can affect his momentum, maybe it can be frozen. After Casey’s ball is found unplayable, Casey takes a drop, with a stroke penalty. Radio Free Fife says, “It smells like a 7.” Whatever the smell of a 7 might be, Casey very quickly is in a position to describe it. His shot flies over the green. Oosthuizen birdies with a fifteen-foot putt, and the duel is over; but before he can bury the corpse Oosthuizen still has to drag it twenty-four hundred yards. Walking up the eighteenth fairway, his final drive just off the green, and seven strokes ahead of the entire field, Oosthuizen at last permits himself (as he soon tells a tentful of reporters) to think that he has won his first major, and to say to himself reassuringly, “I’m definitely not going to ten-putt.” He also reports that, walking up there, he thought of Nelson Mandela. This morning before coming to the golf course, Oosthuizen learned on the Internet that this is Mandela’s ninety-second birthday.

Michael Brown, the chairman of the R&A’s championship committee, thanks the Town of St. Andrews for the use of the golf course. Oosthuizen receives the Claret Jug, his name engraved upon it. Waiting for the press to finish assembling in the Media Centre, he sits on a stage, holds the trophy like a book, and reads it.

Medium: “When did you know you weren’t going to choke?”

Oosthuizen, grinning: “That’s pretty mean, saying ‘choke.’”

Medium: “It seemed remarkable that you and Paul were chatting away when there was such a big prize at stake.”

Oosthuizen: “We have a lot of fun on the course. It’s still just a game you’re playing. Otherwise, it’s going to be quite miserable.”

Between them, Oosthuizen and Casey have just received more than a million pounds. It was the only game in town.

At eight under par, Casey has tied for third with Henrik Stenson and Rory McIlroy. At nine under, Lee Westwood is second (half a million pounds). At sixteen under, Oosthuizen becomes one of the few golfers in history to win a major by seven or more strokes, a list that includes Nicklaus and Woods. A list of those who did not includes Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Sam Snead, and Bobby Jones.

Medium: “You had a temper at one time. It boggles many of us to see how calm you are. Did you get any help to get over that?”

Oosthuizen: “It’s just a matter of growing up, really.”

Oosthuizen’s caddie, Zack Rasego, interviewed by on-course radio: “What’s it like to caddy for him?”

Rasego: “It’s a mixed bag, to be honest with you.”

Radio: “What is your drink of choice?”

Rasego: “Whisky.”

Radio (aside): “He’s in the right place.”

He is also secure in his job, Oosthuizen heaping praise and gratitude on him for many things, from his reading of putts to his bolstering advice down the stretch (“You’ve hit your driver so well—just hit it”). Rasego’s share of the prize is eighty-five thousand pounds.

Rasego: “It’s good to win for South Africa on Nelson Mandela’s birthday today. It’s a fantastic day for us.”

Oosthuizen: “What he’s done for our country is unbelievable. So happy birthday to him once again.”

This is the extent to which Oosthuizen was troubled by St. Andrews’s remorseless wind: “The thing is that wind, to me, it’s a nice wind to use a little cut up against.” Growing up in the Cape winds, Oosthuizen, son of a struggling farmer, was trained and educated at the expense of a foundation set up by Ernie Els, who did not make the cut in this 2010 Open. In Open history, Oosthuizen is the fourth Open champion from South Africa. Ernie Els was the third. Before him, Gary Player won it three times. To encourage Oosthuizen and to offer him advice, Gary Player called him this morning, and spoke with him in Afrikaans.

The first Open champion from South Africa was Arthur D’Arcy (Bobby) Locke in his plus-fours and with his hickory-shafted gooseneck putter winning the Open four times.

Medium: “Do you know much about Bobby Locke?”

Oosthuizen, with jug: “Unfortunately, I don’t. Yeah, unfortunately, I don’t.”

In 2009, Bill Tierney resigned as the men’s lacrosse coach at Princeton and became the men’s lacrosse coach at the University of Denver. He had won six national championships at Princeton, and now he was making, in every respect, including geography, a spectacular jump downscale. I had come to know him well and needless to say regretted his departure, but my interest in the game particularly had to do with its growth—its spreading out from Eastern enclaves—and this was the best example yet.

How would Bill do? Out there in Colorado, how would he get things going? This is how he got things going.