Click here to view a plain text version.

Click here to view a plain text version.

I came in every afternoon to read. I didn’t spend much time with the real Ben at first. Half the time, I had no idea whether he knew who I was. One early “meeting” ended when I asked him how much thought he had put into some of his letters, and he said, “The number of letters I wrote twice you could put in your ear.” Another ended when he started working on a crossword puzzle while I was in the middle of a sentence.

He didn’t have much interest in the stuff I was digging up from the files, either. Whenever I found a letter that I thought was particularly incisive or relevant or funny I would bring it in to him in his office. He would hold it up, scan it for a couple of seconds, and then put it aside with the very clear intention of never looking at it again. I got used to it after a while.

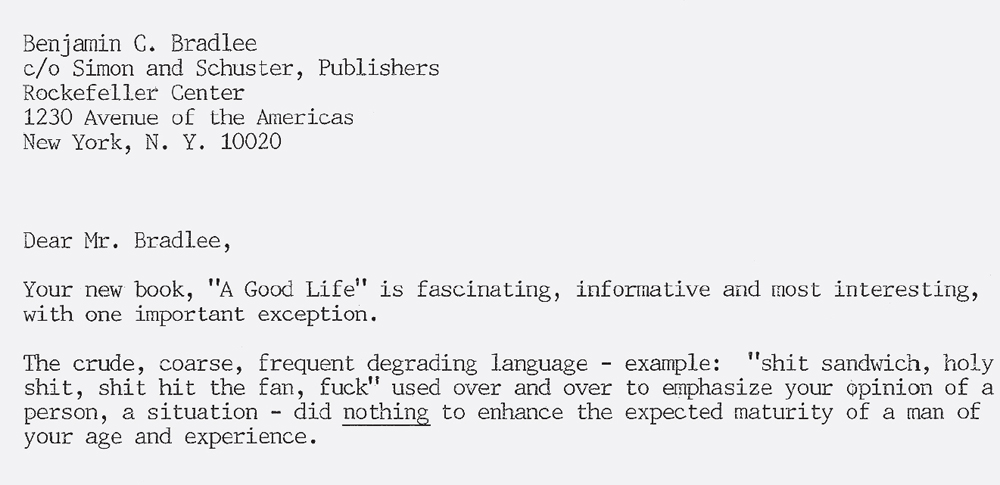

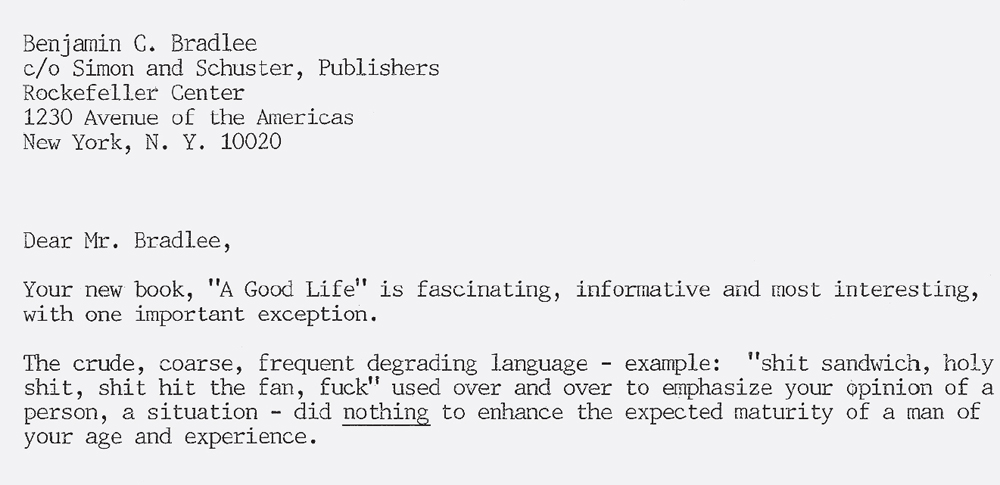

One of the first things you notice about Ben, both the written and the in-person Ben, is his vocabulary, his vernacular, his penchant for one-liners and salty phrases. You don’t have to hang around too long before you’ll get a good, honest “fuck” out of him. It’s a functional component of his charm. I could hear him cursing from the next office over, and so could the rest of the seventh floor. People would poke their heads out of their offices just to hear what he might say next.

Within days I found myself saying “fuck” or one of its equivalents in places where it didn’t belong, under the misguided notion that it would give me street cred with him. I watched other people do it, too. Swearing with Ben makes you feel like you’re part of his club, the club that doesn’t take anything too seriously. Apparently even Kay Graham started doing it, after a fashion. But Ben’s the master, and nobody will tell you differently. He can say the word “fuck” with Mandarin variation and tonal control.

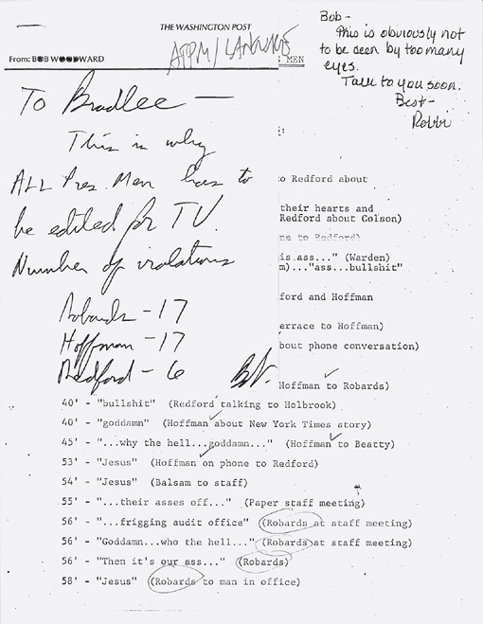

The film version of All the President’s Men is accurate in that regard. Jason Robards, who plays Ben, is constantly spewing curse words. “What kind of a crazy fucking story is this?” he says near the start. Then, later: “Fuck it! We’re sticking with the boys.” The movie had to be edited heavily in order to be shown on TV:1

Click here to view a plain text version.

It’s not just curse words, though. He uses all kinds of different colorful expressions when he wants to cut to the chase. In the middle of an interview with Woodward and Carl Bernstein in 1973, for the book version of All the President’s Men, Ben’s stepdaughter, Nancy Pittman, walked into the room:

BW: We’re interviewing your father just for posterity.

B: They’re writing a book and they’re zeroing in on some of my mistakes.

BW: Do you get any feeling about what your reaction was when Nixon came out and said rather categorically in fact no one is involved—

B: The only one that tightened my sphincter—

BW: [To Nancy] Does he always talk like this around you?

The letters are also dotted with vintage phrases, the kind that only Ben can get away with:

Dear Frank:

I’m late in answering your letter. It isn’t that I have all that goddamn much on my alleged mind, beyond imminent fatherhood, trying to thwart CBS’s plans to steal Woodward for half a million bucks or thereabouts, worrying about some new raspberry plants I just put in, and generally feeling up to my ass in midgets.

A tough situation becomes, in Ben’s mouth, “a basket of crabs”; an unaccomplished rich person a “busted flush”; somebody who disrespects a Washington Post reporter should expect to “hang by his thumbs for a month” before ever seeing his side of a story in print. On a transcribed phone call with a lawyer who had threatened to sue the Post preemptively about a story that hadn’t yet run, Ben began by saying, “I’ve got to tell you that I think that letter has got more bullshit in it per square inch than any letter I’ve received in years. Honest to God.”

Carol, Ben’s secretary, likes to tell the story about the time her son met with Ben because he’d had a problem in college and wanted some advice. After the meeting was over and her son was walking out, Ben clapped him on the back and said, for all of the seventh floor to hear, “Keep your pecker up.”

That’s Ben.

The story that can’t be topped is the one told at Ben’s retirement roast in the newsroom, in 1991, by reporter Tom Lippman:

I had become a sort of freelance guru on style and grammar and usage for people around the newsroom. One day I had an almost hesitant, almost blushing visit from Debbie Regan, who many of you will remember … was Ben’s secretary at the time. Ben had been dictating a letter on that little tape recorder, I guess, which Debbie had to transcribe, and she came over to my desk looking extremely uncomfortable.

She hemmed and hawed a little bit and she said, “Look, I have to ask you something.”

I said, “Yeah, what is it, Debbie?”

She said, “Is dickhead one word or two?”

One night early on I rode out with him to the University of Maryland for a symposium in honor of Shirley Povich, the late and celebrated sportswriter for the Post. Ben loved Povich. He always says that when he first came to the Post, in 1948, Shirley Povich and the cartoonist Herblock were The Washington Post, the only true assets the paper had. Everybody on the panel was telling sports stories, and after a while Ben got bored. A couple of times he stuck both legs straight out in front of him and looked at his shoes, like a boy would. All the talk of blogs and the Internet wasn’t doing much for him.

Then George Solomon, the former editor of the Post’s sports section, began to tell an anecdote about how Povich had helped integrate the press box at one sporting event or another. “Now this is a great story,” Solomon said, launching into it with gusto.

He had barely gotten the words out of his mouth before Ben stirred on the other side of the stage. “We’ll tell you if it’s a great story, George,” he said.

The crowd laughed, and so did the panelists. It did not require any great leap of the imagination to see a younger version of this man presiding as executive editor over a raucous story conference at the paper, cracking people up while also putting them in their place.

“It’s good to know that at your age you still know how to take a cheap shot,” Solomon said, blushing, amused, entirely unoffended.

At one point Michael Wilbon, the ESPN host who was then still a Post sports columnist, started talking about how much he had revered The Washington Post before he went to work there as an intern in 1979. He talked about how excited he had been to come to the paper that Ben Bradlee ran, how mythic Ben and the Post were in his own mind because of Watergate. He had watched All the President’s Men the night before his first day on the job, he said. He was almost misting up about it.2

As Wilbon was wrapping up his spiel, the audience collectively caught sight of Ben in the next chair over. He was sawing on an improvised air violin and rolling his eyes for effect. The gesture was expertly timed and executed, playing to an audience Ben knew would be watching. He was poking fun at Wilbon for being sentimental but also showing that he didn’t take his own mystique too seriously. The crowd roared, even Wilbon laughed. He’d been had by his old boss, and he loved it.

I’ve seen Ben whip that violin out on any number of people since then. He’s pretty ruthless. When Sally got up at his eighty-eighth birthday party and started talking about how Ben was her hero, he didn’t waste much time with it, either. When the spirit moves him, nobody is safe—not his wife or his friends, not other journalists or esteemed fellow panelists or anybody else. One step too far into sentimentality or self-importance and blam, there he is, taking the air out of the situation, showing you your pomposity (or preemptively leavening his own), demonstrating to everybody else that he’s on to you. The mocking is almost always gentle; everybody laughs, because Ben is unfailingly charming and it’s all in good fun. But the message is clear, consistent, unmistakably Ben down to its core: Cut the crap, keep it moving, save the self-serving details. Just get it out of your typewriter, kid.

1 According to Gary Arnold, who reviewed the movie in the Post in April of 1976, Robards’s performance single-handedly “liberalized the ratings system, making the most famous sexual four-letter word of them all acceptable for the PG classification as long as it isn’t spoken in a sexual context.”

2 Wilbon retired from the Post in December of 2010, and in his final column he talked about “the complete awe, even 30 years later, I still feel whenever I’m in the company of Ben Bradlee, even if it’s just seeing him in the elevator.”