10

Repetition: A New Philosophy of Life

The season has turned, control of the country has changed hands, and he looks out from new windows, but the night sky is unchanged. And he can imagine the sea, close by, resting on this quiet night. He tries to open his soul to this sea, deep and transparent beneath the stars; it is possible, for a few moments, to let himself ‘rest transparently in God’, as he has described the experience of faith in The Sickness unto Death. This is one of his favourite thoughts. ‘When the sea exerts all its might, then it is precisely impossible for it to reflect the image of the heavens, and even the smallest movement means that the reflection is not quite pure; but when it becomes still and deep, then heaven’s image sinks down into its nothingness,’ he wrote in 1844. ‘Just as the sea, when it is still, deep and transparent longs for the heavens above, so too does the heart that has become pure long for the good. And as the sea reflects the vault of heaven in its pure depths, so too does the heart that has become still and deeply transparent reflect the heavenly sublimity of the good in its pure depths,’ he wrote last year, 1847. There is always longing in this stillness – a longing that touches what it longs for, and desires it all the more. When he lets his longing for God fill and expand his soul, everything else is silenced.

It is October, and earlier this month he changed addresses for the second time in 1848. Unable to bear the smell of the tanner’s yard below, he leased another ‘fine and expensive’ apartment on the same street, Rosenborggade. Copenhageners move house only on the ‘Flitting Day’ that falls every April and October, ‘when all the furniture of the town is exchanging quarters, and the streets are full of straw, feathers, dust, and every abomination’. In a sense, this practical disruption has done him good, for it forced him to write less strenuously: ‘Here, too, Governance came to my assistance and turned my mistake into a good. If anything helps me to be less productive and diminish my momentum and generally limit me, it is finite anxieties and inconveniences.’ He has also been worried about money. The bonds he bought with the cash from the sale of 2 Nytorv were quickly devalued as the political situation in Denmark became unstable, and he has lost hundreds of rix-dollars. ‘It was no doubt good,’ he has reflected, ‘that I became thoroughly aware of it in time. It also helps to burn away whatever selfishness there is in me and my work.’

Despite these upheavals and distractions, he worked on The Point of View for My Work as an Author as the October elections came and went. Having explained the spiritual origins of Either/Or, he has now turned to consider the very different work that followed it in the spring of 1843 – a slender pamphlet containing two sermons. ‘What is most important often seems so insignificant’: his first two discourses were ‘a little flower under the cover of the great forest’, and they received little attention. Although he was never on better terms with ‘the public’ than in the second or third month after Either/Or was published, what he produced during those weeks seemed to be of little consequence to readers who had excitedly devoured the ‘Seducer’s Diary’. Yet those quiet, unassuming pages introduced his crucial philosophical ‘category’, that single individual, in which ‘a whole life-view and world view is concentrated’ – and at that very moment he ‘made a break with the public’. This is not a new category, but an ancient one: he borrowed it from Socrates, ‘the most eccentric of men’. But in 1848 it has become more important than ever, for ‘if the crowd is the evil, if it is chaos that threatens, there is rescue in one thing only, in becoming the single individual.’

It was just before he took his second trip to Berlin in May 1843 that he arranged for his two sermons to be published by P. G. Philipsen, who ran a fairly new bookshop and publishing house on Købmagergade specializing in works of popular science. One sermon was on ‘The Expectancy of Faith’, which also became the central theme of Fear and Trembling; the other was on his favourite New Testament text, from the Letter of James: ‘Every good and every perfect gift is from above and comes down from the Father of lights, in whom there is no change or shadow of variation.’ Two Upbuilding Discourses was the first of several slim volumes of literary sermons on biblical texts, and he has continued to keep his religious discourses, signed in his own name, separate from the pseudonymous works published by Reitzel.

Although he dedicated Two Upbuilding Discourses to his late father, he gave it a brief preface – dated 5 May 1843, his thirtieth birthday – addressed to ‘my reader’. Here he explained that his discourses could not be called sermons because he was not ordained, and had no authority to preach. He described his little book setting out on its journey to meet ‘that single individual whom with joy and gratitude I call my reader, that single individual it is seeking, to whom, so to speak, it stretches out its arms’.

And it was during that fertile time that Kierkegaard drew the deepest philosophical lessons from his personal experience, beginning with his first appeal to the ‘single individual’ on his birthday, and continuing in his writing in Berlin that May. Yet he has not disclosed – neither in 1843, nor now in 1848 – that when he wrote his preface to Two Upbuilding Discourses he was thinking particularly of Regine: ‘my reader, because this book contained a little hint to her’. With Regine in mind, he wrote with an affectionate intimacy, laced with longing, to a ‘single individual’ – but he quickly realized that he could also address many unknown readers in this way. In late April 1843 he had a surprising encounter with the typesetter of his manuscript:

Quite strange, really. I had decided to change that little preface to the ‘Two Sermons’, since it occurred to me that it harboured a certain hidden spiritual eroticism … I rush up to the printer’s. What happens? The typesetter begs me to keep the preface. Although I laughed a little at him, to myself I was thinking: Well let him be the ‘single individual’! It was my delight at this that at first made me decide to have only two copies printed and to present one of them to the compositor. It was really wonderful to see his emotion. A typesetter – who you would have thought must be just as tired of the manuscript as an author!

Exhilarated by this new thought about how his writing might affect countless single individuals, he set off for Berlin, hoping to repeat the amazing productivity of his first visit to the city. When he got there, though, he was drawn back to the original ‘single individual’. Familiar sights and sounds evoked memories of his arrival in 1841, when he was still reeling from the break with Regine, and summoned old emotions: loss and grief, guilt and shame, self-doubt and anxiety, the sense of exile from ordinary life – and then the habitual lapses into self-pity and defiant self-justification. ‘The day after my arrival I was in a very bad way, on the brink of collapse,’ he wrote to Emil Boesen on 10 May 1843. Already in Stralsund, where he arrived by steamship from Copenhagen, he had ‘almost gone mad hearing a young girl play on the piano Weber’s last waltz’ – for when he came to Berlin before, this was the first piece he heard in the Tiergarten, ‘played by a blind man on a harp’.

The whole city conspired to remind him of his younger, freshly wounded self. As before, he spent his first couple of nights at the luxurious Hotel de Saxe on the bank of the River Spree: ‘I have a room looking out on the water where the boats lie. Heavens, how it reminds me of the past. In the background I have the church – and when it sounds the hours the chimes go right to the marrow of my bones.’ He then returned to the house on a corner of Gendarmenmarkt, where he had lived during his first visit. Then he had occupied the second floor – ‘But the owner has married and therefore I am living like a hermit in one room, where even my bed stands,’ he wrote to Emil.

View of the Spree and the Lustgarten from the Hotel de Saxe in Berlin

Former habits were immediately revived, as if the city had stored them safely for him, ready for his return. He resumed his daily walks along Unter den Linden; it seemed ‘as if everything were designed just to bring back memories’, for even those things that had changed since his previous trip evoked feelings from the past. His newly married landlord, ‘a confirmed bachelor’ less than two years earlier, explained his change of heart: ‘One lives only once, one must have someone to whom one can make oneself understood. How much there is in that; especially when said with absolutely no pretension. Then it hits really hard.’

A year and a half after leaving Regine, he was still trying to make sense of his own change of heart. Having proposed to her and then confronted his deep conviction that he could not marry, he had to break the engagement to remain true to himself – true to his emerging sense of who he was, and what his life should be. And yet his thoughts kept returning to Regine; he wore her engagement ring, refashioned into a diamond cross. Since they parted he had prayed for her every day, often twice a day. And so this second trip to Berlin brought to life a philosophical problem, entwined with the question of fidelity that preoccupied him: Who was he, Søren Kierkegaard, and how did he endure through time? Were the threads of memory connecting him to the past strong enough to secure his identity amid the constant flow of experiences and encounters? Did an eternal soul rest within him as he moved through changing landscapes? Could he find himself only by going backwards, and recollecting who he used to be? Should he be thus tethered to the past, when life must be lived forwards?

As his past life assailed him in the Tiergarten, on Gendarmenmarkt, beneath the blossoming trees along Unter den Linden, he thought about how he might find constancy through repetition. A faithful husband returns to his wife every night; a faithful Christian returns to God every day in prayer, every Sunday in church; a mother’s thoughts return continually to her child. Through such repetitions people keep their promises, and endure through time. They return to themselves, but by stepping forwards, not by thinking back – and this is how human beings remain true to their loves. With each step he took on his long journey to Moriah, Abraham repeated his leap of faith; with each step on the way home, he rejoiced again in the gift of Isaac. In every little movement he renewed his trust in God.

Yet the more Kierkegaard contemplated repetition, the more it puzzled him. Strictly speaking, it is impossible to repeat anything, for what was new the first time becomes familiar the second time, and so altered; the third time will strengthen memories or habits from the second time. The very act of repetition produces these differences – as if repetition continually thwarts itself! Repeating his previous experience in Berlin connected him to his former self, yet also made him conscious of the time that had passed, and how he had changed in the intervening months. Returning to this familiar place put him directly in touch with the deep paradox of constancy and change, sameness and difference, that makes repetition so elusive.

Inspired by his philosophical discoveries, Kierkegaard spent those spring days in Berlin writing furiously. Each morning he returned to the café he had frequented during his first visit to the city, which had ‘better coffee than in Copenhagen, more newspapers, excellent service’. Then he set to work. Once he had recovered from the long journey – the overnight steamship, the dreadful stagecoach and the miraculous train – he found that the change of scene did him good. ‘When one does not have any particular business in life, as I do not,’ he wrote to Emil Boesen on 15 May, ‘it is necessary to have an interruption like this now and then. Once more the machinery within me is fully at work, the feelings are sound, harmonious, etc.’ That was less than a week after his arrival in Berlin, but he could tell his friend that ‘I have already achieved what I might wish for … now I am climbing.’

He rapidly transmuted his experiences of repetition and recollection into a philosophical text, filling two notebooks with a draft of Repetition. As he relived his memories, he set out an original critique of Plato’s doctrine of recollection, drawing on notes he had taken with him to Berlin. During the first months of 1843 he had gained a deeper understanding of Plato by studying the Greek philosophers who came before and after him: he read about the Eleatics, the Sceptics, the Cynics, the Stoics and Aristotle. He used a notebook, labelled ‘Philosophica’, to record details of the Greeks’ metaphysical theories, cribbed from a German textbook on the history of philosophy. This notebook also contained a series of unanswered questions, each one written at the top of a blank page: What do I learn from experience? What is the universally human, and is there anything universally human? What is the self that remains behind when a person has lost the whole world and yet has not lost himself?

Sketch of Kierkegaard reading in a café, 1843

That last question echoed the one from Mark’s Gospel which he wrote in his journal on the day he first met Regine in 1837: ‘What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world, but loses his own soul?’ Six years later, this question was reversed: one world, at least, had been lost – but where was the self he had hoped to gain? He realized that these deep philosophical questions replayed within his own soul the debates among the ancient Greeks, who contemplated the cosmos as they contemplated themselves, trying to discover the secrets of existence.

First there was Heraclitus, who taught that everything is in motion. The whole of nature flows like a river, blazes like a fire, substanceless, essenceless, and this was the only truth he knew, for he could experience it. Turning his attention inwards, Heraclitus felt sensations flowing, emotions blazing. But Parmenides found timeless truths in mathematics: he believed these fixed relations to be truly real, and all the shifting things which appeared to his senses – the winds, the seas, the stars – mere illusions. His followers the Eleatics, among them Zeno with his famous paradoxes, argued that motion and change were logically impossible. How could anything new come into being? Either there is nothing, or there is something; and where is the time for becoming in between these contrary states of absence and presence? Plato’s pupil Aristotle tried to solve this paradox by defining change as a movement from potential existence to actual existence: the new qualities that emerge as a tree grows to maturity – branches, leaves, fruit – were already potentially present, though not yet actualized, in the seed. And as a tree stretches its branches, leaves seeking the light, it shows a human being his own nature. ‘The secret of all existence: movement,’ Kierkegaard wrote in his notebook.

Those studies of ancient Greek philosophy helped him to see how Plato’s doctrine that knowledge is recollection responded to an ancient question about the connection between movement and truth. Plato taught that human lives are stretched between time and eternity: between Heraclitus’ world of change and becoming, and Parmenides’ ideal, timeless truths. Plato agreed with Parmenides that truth is unchanging – yet our embodied lives begin, unfold and end within this changing world. This is our place of learning, our academy: on its return journey to eternity, each soul travels through the world of becoming, which offers reminders of timeless truths. At the sight of a beautiful woman, the soul recollects an immortal, incorruptible beauty; when it is touched by the partial, relative goodness of a human act, it recollects the immaculate Idea of the Good, impartial and absolute. Plato argued that knowledge concerns what is unchanging – but he also emphasized that knowing is itself a movement, a pursuit, in the direction of eternity. Inspired by Socrates, he taught that living a truly human life means making this movement of recollection.

Armed with these insights into the dawn of European philosophy, Kierkegaard began Repetition with an elliptical critique of the whole tradition, from the ancient Greeks to the modern Germans – for Hegel had also analysed the movement of knowledge, showing how one concept emerges logically from another in a dialectical pattern that leads progressively towards an absolute truth. In Repetition Kierkegaard turned Plato’s term ‘recollection’ into an epithet for the process of thinking which converts life into ideas, in an attempt to understand it. Recollection produces truth in the form of knowledge, but when a human being asks how he himself can be true – true to another person, or true to God, or true to himself – he is concerned not with a truth to be known, but with a truth to be lived. This truth is a matter of fidelity, constancy, integrity, authenticity. Conscious of the fluctuations in his soul, and still mostly in the dark about who he was and who he might become, Kierkegaard wondered how he could promise to be faithful to others, knowing that his mind might change. And how can any human being, whose existence is continually in motion, accomplish constancy in relation to God?

The answer to all these questions, which he wrote out in his small, slanting hand in that single room on Gendarmenmarkt, is repetition. A relationship – whether to another person, to God, or to oneself – is never a fixed, solid thing. If it is to endure through time, it must be repeatedly renewed. And each human self is made up of such relationships. The ‘new category’ of repetition would, Kierkegaard argued, finally allow philosophy to say something meaningful about the truth of life.

Meanwhile, he was struggling to reconstruct the truth of his own life – for Repetition was the revised story of his engagement crisis as well as a manifesto for existentialism. He embedded his metaphysical reflections within an experimental psychological narrative, dividing himself, once again, between two characters: an amateur philosopher called Constantin Constantius who travelled twice to Berlin, and his friend, a young man who wanted to break up with his fiancée and become a writer. Both these men were foolish, though in different ways. They played out a story composed from episodes in Kierkegaard’s life, loosely following the model of Goethe’s early epistolary novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, a founding text of Romantic literature, which had already inspired F. C. Sibbern, Kierkegaard’s former philosophy professor, to write a similar kind of novel.

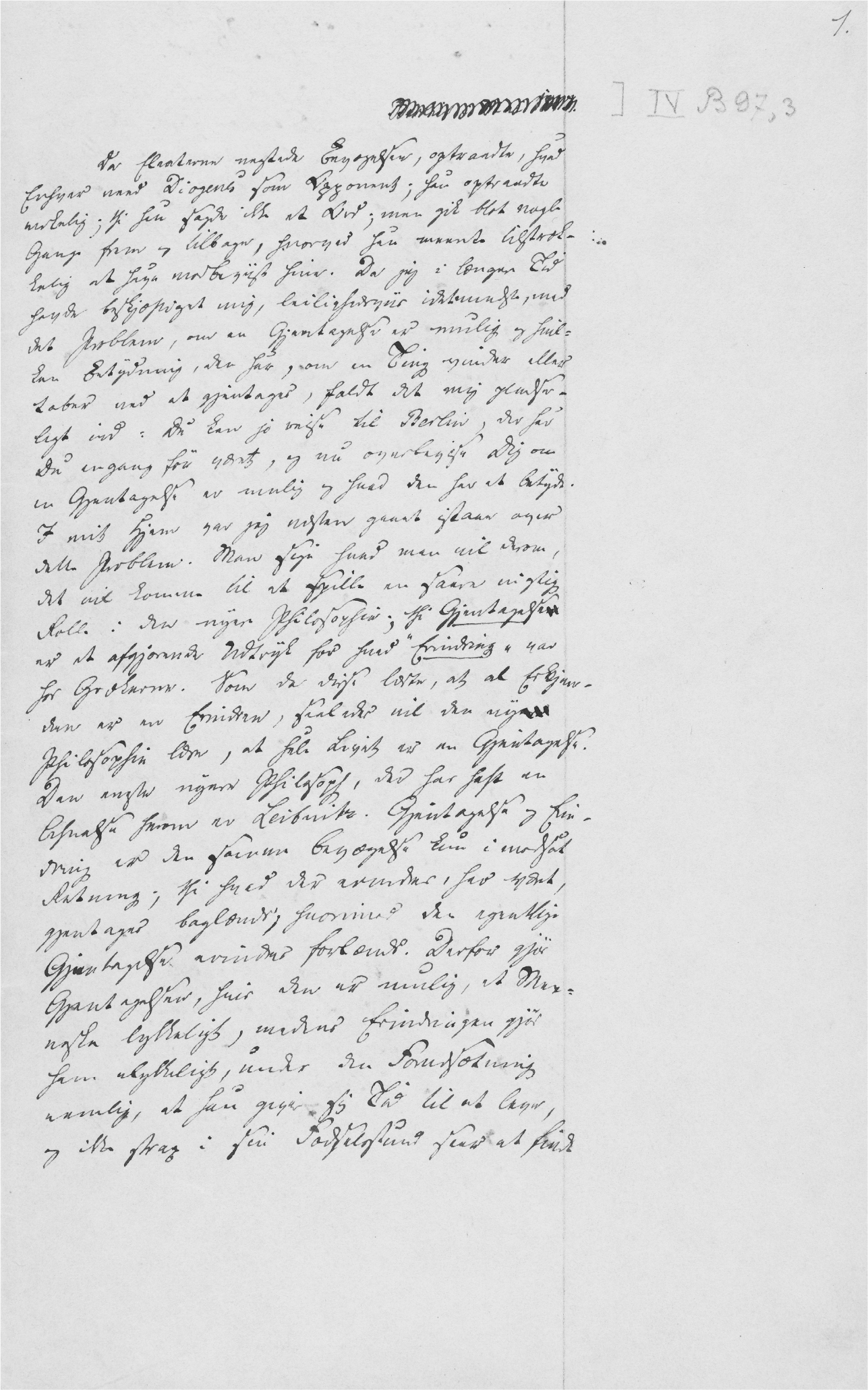

Manuscript of Repetition: first page

Repetition ’s narrator, Constantin Constantius, proposes a new theory of truth, but despite his erudition he does not fully understand his own theory. Writing in the voice of this character allowed Kierkegaard to stake his claim as a philosopher while pointing out the limits of a purely intellectual approach to questions of existence. ‘The question of repetition will play a very important role in modern philosophy,’ announces Constantin boldly, after dropping an insouciant reference to Leibniz’s metaphysics, ‘for repetition is a crucial expression for what “recollection” was to the Greeks. Just as they taught that all knowing is a recollecting, so modern philosophy will teach that all life is a repetition … Repetition is the new category that will be discovered!’

Having sketched out his theory of repetition in a few cryptic paragraphs, Constantin Constantius decides to test it by returning to Berlin, a city he has visited once before. While other well-off Danes travel abroad to see notable sights or to ride on a train – or, if in London, to take a carriage through the new tunnel under the Thames – Constantin likes to travel with no particular purpose except to observe people and philosophize. His ‘investigative journey’ will be an experiment in ‘the possibility and meaning of repetition’.

In Berlin, Constantin returns to his former lodgings on Gendarmenmarkt, in order to discover ‘whether a repetition is possible’. He has fond memories of this place:

Gendarmenmarkt is certainly the most beautiful square in Berlin; das Schauspielhaus [the theatre] and the two churches are superb, especially when viewed from a window by moonlight. The recollection of these things was an important reason for taking my journey. One climbs the stairs to the first floor in a gas-lit building, opens a little door, and stands in the hallway. To the left is a glass door leading to a small room. Straight ahead is an anteroom. Beyond are two entirely identical rooms, identically furnished, so that one sees the room double in the mirror. The inner room is tastefully illuminated. A candelabra stands on a writing table; a gracefully designed armchair upholstered in red velvet stands before the desk. The first room is not illuminated. Here the pale light of the moon blends with the strong light from the inner room. Sitting in a chair by the window, one looks out on the great square, sees the shadows of passers-by hurrying along the walls; everything is transformed into a stage setting. A dream world glimmers in the background of the soul. One feels a desire to toss on a cape, to steal softly along the wall with a searching gaze, aware of every sound. One does not do this but merely sees a rejuvenated self doing it. Having smoked a cigar, one goes back to the inner room and begins to work. It is past midnight. One extinguishes the candles and lights a little night candle. Undiluted, the light of the moon reigns supreme. A single shadow appears even blacker; a single footstep takes a long time to disappear. The cloudless arch of heaven has a sad and pensive look as if the end of the world had already come and heaven, unperturbed, were occupied with itself. Once again one goes out into the hallway, into that little room, and – if one is among the fortunate who are able to sleep – goes to sleep.

Alas, reality does not match Constantin’s dreamy recollection of his Berlin residence – part theatre, part Platonic cave, part writing retreat – with its secluded view on the world. Since his previous visit, the owner of the house has married, and only one room is available for rent. More disappointments quickly follow. Constantin goes to the Königstädter Theatre to see the same actors play in the same farce he enjoyed last time: he remembers sitting in the quiet theatre, alone in a box, and abandoning himself to laughter – but on this second visit the theatre is busy, none of the boxes are empty, he cannot get comfortable, and the play does not amuse him; after half an hour he gives up and leaves. He returns to his room, where the splendour of the red velvet chair seems to mock his cramped living quarters. The lighting is all wrong. He sleeps badly that night.

The next morning, as he tries to work, thoughts of the past prevent him from philosophizing:

My mind was sterile, my troubled imagination constantly conjured up tantalizingly attractive recollections of how the ideas had presented themselves the last time, and the tares of these recollections choked out every thought at birth. I went out to the café where I had gone every day the previous time to enjoy the beverage that, according to the poet’s precept, when it is ‘pure and hot and strong and not misused’, can always stand alongside that to which the poet compares it, namely, friendship. At any rate, I am a coffee-lover. Perhaps the coffee was just as good as last time; one would almost expect it to be, but it was not to my liking. The sun through the café windows was hot and glaring; the room was just about as humid as the air in a saucepan, practically cooking.

Every attempt to relive his recollections is frustrated, and Constantin becomes ‘weary of repetition’. ‘My discovery was not significant, yet it was curious,’ he reports, ‘for I had discovered that there is simply no repetition, and had verified it by having it repeated in every possible way.’

Meanwhile, Constantin’s friend is caught in a different kind of recollection. This young man, whose ‘handsome appearance, large glowing eyes, and flippant air’ appeal to Constantin, is ‘deeply and fervently and beautifully and humbly in love’. But he is melancholy: his love for his fiancée has quickly turned into longing, even mourning, and he has begun to ‘recollect his love’. Having turned her into a fixed idea, which he can summon and sigh over at will, he no longer relates to her as a living person. Constantin observes that his friend is ‘essentially through with the entire relationship’, though he does not yet know this himself: ‘It was obvious that he was going to be unhappy; that the girl would also become unhappy was no less obvious, although it was not so immediately possible to predict how it would happen … Nothing could draw him out of the melancholy longing by which he was not so much coming closer to his beloved as forsaking her. His mistake was incurable, and his mistake was this: that he stood at the end instead of at the beginning.’

The young man gradually realizes that there has been ‘a misunderstanding’ between himself and his fiancée, and as she becomes ‘almost a burden to him’ Constantin sees ‘a remarkable change’ in his friend: ‘A poetic creativity awakened in him on a scale I had never believed possible. Now I easily grasped the whole situation. The young girl was not his beloved: she was the occasion that awakened the poetic in him and made him a poet. That was why he could love only her, never forget her, never want to love another, and yet continually only long for her. She was drawn into his whole being; the memory of her was forever alive. She had meant so much to him; she had made him a poet – and in doing this she had signed her own death sentence.’

When Regine read this, she would find a new explanation for Kierkegaard’s behaviour: while Either/Or perpetuated the deception that he had callously used her, Repetition suggested that he loved her exclusively, in the only way he was capable of loving any woman. This book also exposed his previous strategy of subterfuge. ‘Transform yourself into a contemptible person,’ Constantin advises his friend – this will allow his fiancée to become ‘the victor’, for then ‘she is absolutely right and you are absolutely wrong.’

Kierkegaard’s resentment and indignation towards Regine gleamed through these thoughts of self-sacrifice. ‘I cannot deny that I gradually came to regard the young man’s beloved with a prejudiced eye,’ admits Constantin: ‘That she should notice nothing whatever, that she had no suspicion of his suffering and of the reason for it, that if she suspected it she did nothing, made no effort to save him by giving him the one thing he needed and which she alone could give him, namely, his freedom.’ He believes that feminine love should be sacrificial, that a woman becomes masculine if she has enough ‘egotism’ to imagine that ‘she proves the fidelity of her love by clinging to her beloved instead of giving him up.’ Such a woman, he contends bitterly, ‘has a very easy task in life, which permits her to enjoy not only the reputation and consciousness of being faithful, but also the most finely distilled sentiment of love … God preserve a man from such fidelity!’ And in any case, Constantin didn’t find this woman particularly special; he is amazed that she had such significance for his friend, ‘for there was no trace of anything really stirring, enrapturing, creative. With him it was as is usually the case with melancholy people – they trap themselves. He idealized her, and now he believes that she was that … What traps him is not the girl’s lovableness at all but his regret at having wronged her by upsetting her life.’

These pages of Repetition echoed a journal entry written in Berlin on 17 May 1843, where idealistic love and romantic regret battled with angry, self-justifying complaints about Regine’s ‘pride’ and ‘arrogance’. During and after the break-up, Kierkegaard tried to play the hero by playing the villain, feigning indifference and cruelty, and sacrificing his reputation to make her feel happier about losing him. He resented this role, and he resented Regine too for not letting him go more easily, for making him feel – and look – so guilty. As usual, the sensitivity which makes him so compassionate to others also distorted his sense of injury; defensiveness stifled his generosity, and he reacted harshly. ‘Humanly speaking I have been fair to her,’ he protested. ‘In a chivalrous sense, I loved her far better than she loved me, for otherwise she would neither have shown me pride nor alarmed me later with her shrieking … I have behaved most magnanimously towards her in not letting her suspect my pain.’

While Constantin criticizes the fictional version of Regine, the young hero of Repetition cannot let her go. Kierkegaard’s inner conflict and confusion were refracted through the ambivalent relationship between these two characters: Constantin finds his friend ‘quite irritable, like any melancholic, and despite this irritability as well as because of it, in a continual state of self-contradiction. He wants me to be his confidant, and yet he does not want it.’ The young man is appalled by Constantin’s cool, detached attitude to his situation. He leaves town, and writes letters to Constantin: he reports that he is sinking in recollections of his beloved; that he has read the Old Testament story of Job, who protested his righteousness when God took everything from him; that he is ‘nauseated by life’; that he agonizes over his guilt about breaking the engagement; that, in spite of all appearances, he is in the right.

‘I am at the end of my tether,’ begins one letter:

My whole being screams in self-contradiction. How did it happen that I became guilty? Or am I not guilty? Could I anticipate that my whole existence would undergo a change, that I would become another person? Can it be that something darkly hidden in my soul suddenly burst forth? But if it lay darkly hidden, how could I anticipate it? But if I could not anticipate it, then certainly I am innocent. Am I unfaithful? If she were to go on loving me and never loved anyone else, she would then certainly be faithful to me. If I go on wanting to love her, am I then unfaithful? Why should she be in the right and I in the wrong? Even if the whole world rose up against me, even if all the scholastics argued with me, even if it were a matter of life and death – I am still in the right. No one shall take that away from me, even if there is no language in which I can say it. I have acted rightly. My love cannot find expression in a marriage. If I do that, she is crushed. Perhaps the possibility appeared tempting to her. I cannot help it; it was that to me also.

As he reads the young man’s tormented, passionate letters, Constantin understands that repetition is ‘a religious movement’. He realizes that he was foolish to seek repetition in external things – a theatre, a coffee shop, a writing desk and a velvet chair – for true repetition is an inward, spiritual movement wherein a human being receives himself anew. Job obtained repetition when everything he had lost was restored to him, even more plentifully than before; Abraham obtained it when God renewed his gift of Isaac, and he ‘received a son a second time’. Constantin also sees that he cannot accomplish such a repetition: ‘I am unable to make a religious movement, it is contrary to my nature.’

The young man, meanwhile, hopes for an inward repetition that will restore the freedom he lost when he became romantically ensnared. Perhaps he can regain this freedom if he stops claiming to be in the right, and asks forgiveness for his mistakes – but this seems to be contrary to his nature. Instead, inspired by the Book of Job, he demands a divine miracle: ‘Make me fit to be a husband, shatter my whole personality, render me almost unrecognizable to myself.’ As he waits for grace to strike, he tries to change himself – to become a man who can be true to his love: ‘I sit and clip myself, take away everything that is incommensurable in order to become commensurable. Every morning I discard all the impatience and infinite striving of my soul – but it does not help, for the next morning it is there again. Every morning I shave off the beard of all my ludicrousness – but it does not help, for the next morning my beard is just as long again.’

By the end of Repetition the fiancé is desperate, as convinced of his righteousness as Job, yet incapable of repetition. Eventually, despairing of reform, despairing of release, he follows the example of Goethe’s romantic hero Werther, who has already inspired many sensitive young men to suicide. Seeing no way forward, all hope exhausted, Kierkegaard’s alter ego takes a pistol and shoots himself in the head.

Boarding the train in Berlin at the end of May 1843, he hardly knew how a mess of scribbled ideas and a dark tangle of feelings, some of them generations old, had been condensed into this little manuscript. It was barely coherent: its strangeness and obscurity were perhaps inevitable effects of his effort to bring together philosophy and experience, to draw out the universal significance of questions that both shaped and fractured his own life.

Had he solved the problem of how a human being can remain true to his love? He had shown that recollection preserves love only by displaying it like an exhibit behind glass, or keeping it like a lock of hair inside a reliquary – at the cost of denying it life, of closing down the future. He had also suggested that philosophical thinking, which treats truth as an idea to be grasped, is similarly sterile when it comes to making sense of human existence. And he had hinted that this kind of theoretical truth needs to give way to a religious movement – to the ‘good and perfect gifts’ repeatedly given from above to anyone willing to receive them – if human beings are to be true to themselves from moment to moment, through all the minute shifts and momentous upheavals of their lives.

By then, his effort to be true to himself had eclipsed the ideal of being true to Regine in any worldly sense. That year he noted in his journal Socrates’s ‘very fine’ remark in the Cratylus that ‘to be deceived by oneself is the worst thing of all, for how could it not be terrible when the deceiver never disappears, even for an instant, but is always ready at hand?’ Of course, being honest with himself was not exactly comfortable either. Burdened with this absurd ego slumped like a fragile giant upon his shoulders, confronted by his own faults at every turn, still filling pages with his rancour at the young woman who loved him, he reached the conclusion that ‘the main thing is that one is truly forthright with God – that one does not attempt to escape from anything, but pushes on until he himself provides the explanation. Whether or not this will be what one might wish it to be, it is still the best.’

Now, in the autumn of 1848, in his new apartment, he is still ‘pushing on’, still seeking ‘the explanation’ for what happened with Regine, for his authorship, for the man he has become. He can only bare his soul to God at times like this – at home in quiet hours, in solitude. Ancient spiritual teachers taught that ‘to pray is to breathe’, and thus it makes no sense to ask why one should pray: ‘Because I would otherwise die – so it is with praying. Nor by breathing do I intend to reshape the world, but merely to refresh my vitality and be renewed – that is how it is to pray in relation to God.’ He spends most of his time pursuing ‘the explanation’ in another way: in his journals, now in The Point of View for My Work as an Author. But when he holds his beloved pen, thoughts of the reader – whether this is Regine, or Bishop Mynster, or Professor Martensen, or an unknown reader in the distant future, far beyond his death – interpose their folds of reflection between himself and God. Quick and gossamer thin as insects’ wings, barely discernible, these fluttering thoughts pull his gaze in myriad directions. Then his soul, like the sea in a breeze or a misty night sky, loses its transparency. All his thoughts, all his journal notes, ‘are too wordy for me, and yet they do not exhaust everything I carry in my inner self, where I understand myself much more easily in the presence of God, for there I can bring everything together at once, and yet in the end understand myself best by leaving everything to him’.