6

‘Come Unto Me’

In 1848 Easter has fallen later than usual, in the fourth week of April, and as he walks home from the Church of Our Lady after the Easter Sunday service the air feels almost warm. The streets are busy and spirits are high: the crowds swarm happily from the church in all directions, released at last from their Lenten restraint, enjoying the sunshine and looking forward to dinner. When he lived on Nytorv, the Church of Our Lady was less than two minutes away; now he has moved to Rosenborggade, the walk home is a little longer – round the north side of the church, past the university, along the street to the great round tower of Trinity Church; then left into Købmagergade, past the porcelain factory, Reitzel’s bookshop, and the offices of The Fatherland, and up through Kultorvet.

Keeping to the shaded side of the street, Kierkegaard hurries home to write. Nowadays, the sermons he hears in church are fresh fuel for his own religious discourses. The consoling teaching of Bishop Mynster, who leads the Danish State Church from his episcopal residence by the Church of Our Lady, must be countered with rigorous insistence on the difficulty of the Christian life. In his mind, a new paragraph is already dashing across its page. Having drafted a trio of discourses on ‘the Lilies and the Birds’ of Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, he is now at work on another book, a sequel to the still-unpublished Sickness unto Death. While that work diagnosed the varieties of despair from which human beings suffer – many of them unaware of their spiritual disease – this new cycle of discourses proposes a single cure: following Christ. He must show that this is a demanding ideal, if not an impossible task; that Jesus called his disciples out of their comfortable, conventional lives, and set them on a dangerous and uncertain path. In this new work, provisionally titled Come Unto Me (Matthew 11:28), Kierkegaard is opposing the Christian establishment more directly – represented above all by Bishop Mynster, and by the Church of Our Lady, which as Copenhagen’s cathedral provides the model for Christian worship throughout Denmark.

He has lived all his life in this parish, though the Church of Our Lady itself was in ruins when he was born. It burned down when the British navy bombarded the city in 1807 during the Napoleonic Wars. So in June 1813 his parents took him to be baptized in the Church of the Holy Spirit, a few streets to the east of their ruined parish church. On that day Søren Aabye Kierkegaard became both a member of the Danish State Church and a citizen of Denmark – for Lutheran Christianity is so tightly knit into civic life that baptism into the national Church also confers citizenship. It is illegal to deny in print the existence of God, and the penalty is exile from Denmark. Kierkegaard has never come close to atheism, yet his whole authorship defies his baptism by asking, over and over again, whether anyone in this Lutheran country has yet become a Christian.

Although his new home on Rosenborggade is a little further from the Church of Our Lady, through his writing he is drawing closer to it – a characteristically ambiguous movement, as if the closeness tightens his heart, intensifies his long-standing ambivalence towards the religion he inherited not only from his father, but from his native land. Perhaps he is moving towards the Church in order to bombard it from within. His new book advances a sharpened critique of Bishop Mynster, and not only through an interpretation of Christianity that diverges more radically from the Bishop’s own. Mynster’s best-known book is his 1833 devotional work Observations on Christian Teachings, and Kierkegaard will make Mynster his explicit target by attacking the idea that a Christian should be an admiring ‘observer’ of Jesus. No, a Christian’s task is to follow Jesus, to imitate him – and this means suffering like he did.

And he has finally decided to publish his Christian Discourses, a collection of twenty-eight sermons which rivals, in size at least, the weighty volume of Mynster’s sermons that he used to read in 2 Nytorv when he was a boy. Christian Discourses, written last year, will be in Copenhagen’s bookshops in three days, on 25 April 1848. It may be his last book; here, for the first time, the word Christelige will appear in the title of a work by S. Kierkegaard. For years, of course, his authorship has circled around Christian themes. Since 1843 he has written dozens of ‘edifying discourses’ on the spiritual life, taking New Testament verses as their starting point; in 1844 he published Philosophical Fragments, on the ‘absolute paradox’ of the Incarnation, as well as The Concept of Anxiety, a new interpretation of the doctrine of original sin. But those works were written in the guise of fictional authors who addressed religious questions as logicians or psychologists, and refused to describe themselves as Christians. Under such pseudonyms Kierkegaard could approach Christianity obliquely, tentatively, covertly. A few months ago, in the autumn of 1847, he put his own name to Works of Love, a series of ‘Christian Deliberations’ on the commandment to ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ Now he is approaching directly the figure of Christ, who has summoned him, frightened him, and mystified him from his youth.

His questions about how to be a human being are converging on the task of following this compelling, enigmatic figure. Will this narrowing path draw him further into the Church – or take him outside it? This is a new, tightened form of the question that has troubled him persistently: how can he become fully, truly human within the ready-made patterns of life the world has to offer? Is the Church part of this world, or an alternative to it – a sacred refuge, a spiritual garrison, a holy citadel? Where does he go when he goes to church? Does he find any more truth there than in the theatre, or the lecture hall, or the marketplace – or have churches become the least truthful places in Christendom?

In this established Lutheran nation, Kierkegaard is grappling with the legacy of Luther’s own struggle. In the 1520s, while still a monk and a Roman Catholic, Luther argued that the true Church was invisible, a spiritual community formed only by faith, while all the visible buildings and bishops of Christendom were corrupt monuments to his Church’s distortion of the Gospel. Yet Lutheran faith rapidly made itself equally visible – in printed pamphlets adorned with pictures of Luther, in bonfires of books and wooden saints. Converts to Luther’s spiritual church wrested control of physical churches throughout northern Europe – including Copenhagen’s Church of Our Lady. Three hundred years later, this church is, for Kierkegaard, an ambiguous place: is it the house of the Lord, or a house of illusions?

Drawn so powerfully to his spiritual task that he can set no limits to its weight and urgency, Kierkegaard is asking how to express his inner need for God within a Church that offers to meet this need, yet seems often to diminish or divert or falsify it. He can trace this question right back to Jesus, whose teaching broke through the customs and hierarchies of his own religious community. And it runs like a spiritual pulse throughout the Christian tradition, both animating and disrupting it from within. In the Lutheran Churches, this question drove the pietist revivals which pushed at the boundaries of official religion for two centuries after Luther’s death. Pietism put devotion above dogma, spiritual awakening above orthodox belief; this was a religion of the heart, emphasizing pious feeling and conduct rather than creedal formulas. While their Church acquired political power and strengthened its position in the world, many pietists drew on monastic and mystical strands of medieval Catholicism and spoke of renouncing worldly things. For others, Jesus’s teaching inspired a forward-thinking egalitarianism: these pietists were actively anti-clerical and socialist, and put their radical ideas into practice by living in separate communities, largely independent of Church and State. The pietist counter-movement to Lutheran orthodoxy intertwined with Denmark’s official religion to form Kierkegaard’s Christian upbringing, for his father was a member of Copenhagen’s pietist congregation as well as a regular churchgoer. These religious tensions have shaped his soul, just as they have shaped Protestant Christendom: his own spiritual legacy is a miniature rendition of three centuries of Reformation history.

West Jutland, where Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard grew up, was one of the regions of Denmark where Moravian pietism took hold in the eighteenth century. After he moved to the city, Michael Pedersen remained faithful to the pietism of his Jutland family, and it suffused the Christianity he passed on to his own children. Like other pietists, the Moravians aspire to a holy life that follows the example of Christ: they seek to imitate Jesus’s deep, inward faith in God, and his pure-hearted obedience, humility and poverty. Of course, no one can live up to such a demanding ideal – and every effort to do so only makes it clearer that human beings are sinners, in need of divine forgiveness and redemption.

When Michael Pedersen arrived in Copenhagen in the 1760s, the Moravians had been established there for about three decades, and their Society of Brothers was thriving. As he became a prosperous businessman, Michael Pedersen helped to guide the Society’s financial affairs: he advised on the purchase of a larger meeting hall on Stormgade in 1816, and though he was not known to be generous with his wealth he was regarded as one of the group’s most faithful members. During the years of Kierkegaard’s childhood, the Copenhagen Brethren flourished under J. C. Reuss, who came to the city from Christiansfeld, an egalitarian Moravian settlement in east Jutland, planned around an unadorned church and other communal buildings. Reuss’s preaching drew large congregations: on Sunday evenings hundreds of Copenhageners gathered at the meeting house on Stormgade to pray together, sing hymns, and hear ‘awakening discourses’. Each week Reuss reminded the crowds of their moral frailty and deep need for God, and urged them to follow Christ: ‘We know we are sinners, great is our imperfection and weakness and we err often and many times over … Our Saviour takes pity on us, he knows our hearts, knows our sinfulness, knows how we need help, comfort, strength and encouragement in order to live for him in humility, love, and according to his mind and heart. He is also prepared to grant us all his precious blessings, and satisfy our exhausted souls with his gifts of grace. Dear Brothers, he must find our hearts opened for him.’

Michael Pedersen took this message home to his family, and in the 1820s Søren Kierkegaard began to accompany his father and older brothers to the Moravian meeting house. But Michael Pedersen was a solid citizen and a canny merchant as well as a devout man, never likely to sacrifice his hard-won bourgeois respectability to the cause of the more radical, anti-establishment Moravians. His pietist sympathies did not compromise his commitment to the Danish State Church: he went to his parish church every Sunday morning, and to Stormgade on Sunday evenings.

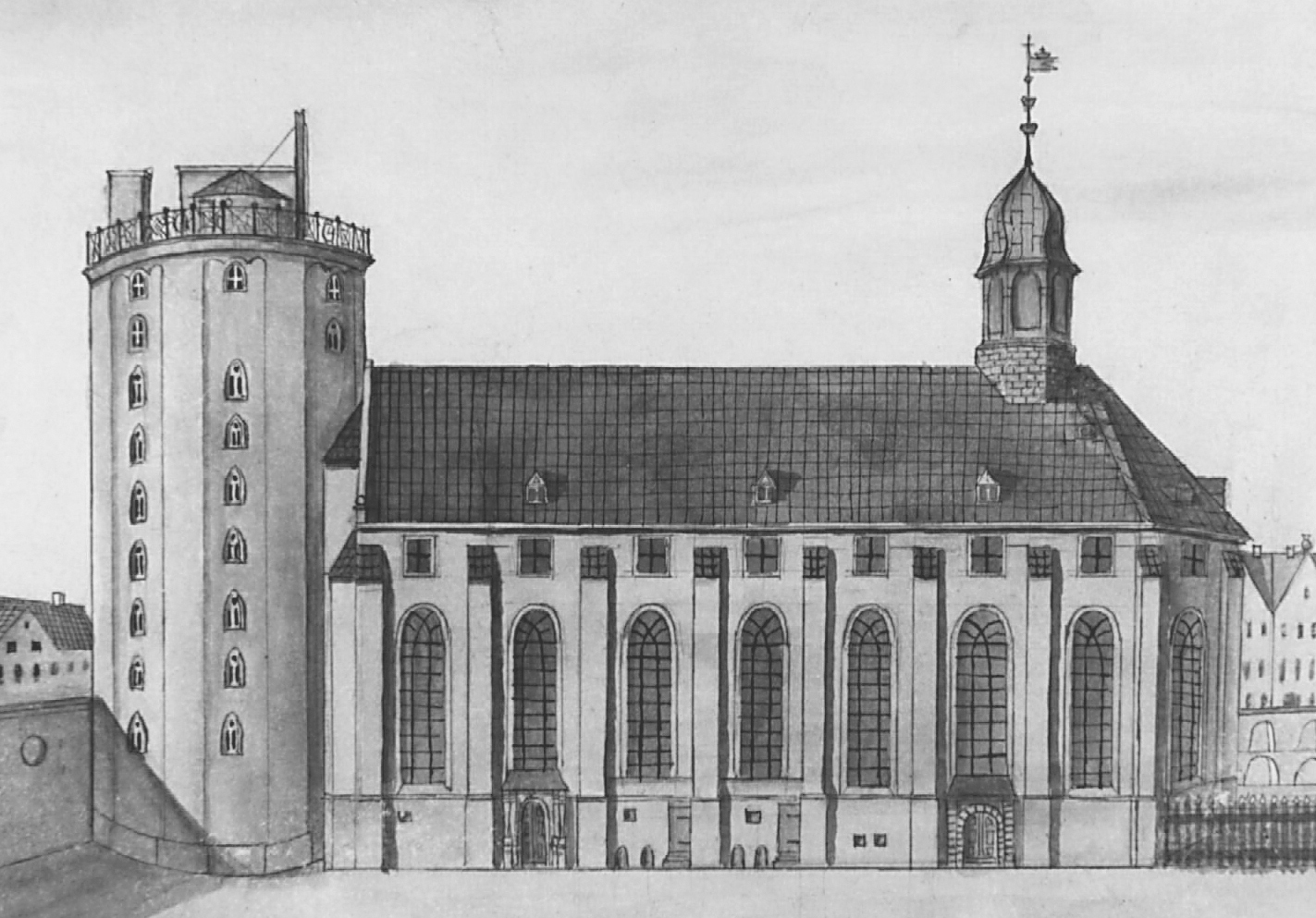

Trinity Church and the Rundetaarn (Round Tower) in 1749

While the Church of Our Lady was being rebuilt, its restoration slowed by Denmark’s dire economic straits after the 1813 crash, its clergy and most of its parishioners worshipped at the nearby Church of the Trinity. This seventeenth-century church combined religion with science and learning: it housed the University Library upstairs, supported by the massive interior columns of the church below, and its adjoining Round Tower was an observatory. During the 1820s Kierkegaard’s father joined the congregation at this grand university church – drawn, like many of his neighbours, by Jakob Peter Mynster, the charismatic senior pastor of Our Lady’s parish. Mynster’s presence ‘inspired reverence’: those who met him not only admired his ‘warmth of heart, and dignity of character’, but felt themselves uplifted by the way he embodied ‘the pure loveliness of a human soul fashioned into Christ’s divine pattern’. Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard went to Mynster for confession and communion, and took his family to Sunday services, where Mynster usually preached the sermon. So it was Mynster who confirmed Kierkegaard in the Church of the Trinity in April 1828, just before his fifteenth birthday, and it was Mynster who officiated at his first communion.

It was not only formally that Mynster initiated Kierkegaard into the Danish State Church: throughout his formative years this priest was his most influential Christian teacher and exemplar. He grew up on Mynster’s eloquent, stirring sermons, which were frequently read in 2 Nytorv as well as heard in Trinity Church. Kierkegaard remembers how, when he was a boy, his father promised him a rix-dollar if he would read one of these sermons aloud to him, and four rix-dollars to write up the sermon Mynster had preached in church that Sunday. And he remembers how he refused, though he wanted the money, and told his father that he should not tempt him in that way. Michael Pedersen’s great respect for his pastor imbued Mynster with vicarious paternal authority, which inspired in Kierkegaard the same potent mixture of sincere, overt reverence and deep, concealed defiance that he felt towards his father.

Jakob Peter Mynster by Constantin Hansen

Mynster was born in 1775, almost twenty years after Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard. He was orphaned in childhood, and the austere Christianity of his pietist stepfather injured his innate religious sensibility. Even after he became a parish priest in south Zealand, Mynster felt unsure of his vocation. But this changed in 1803, when he experienced a profound spiritual awakening, and all his doubts were assuaged by a deep trust in his own conscience, the voice of God within him. He resolved to obey this inner voice unconditionally, and in submission to it he found lasting peace. From then on, week after week, Mynster exhorted his congregations to follow their conscience, and assured them that their earnest moral efforts would be rewarded with peace and happiness. He began to publish his sermons. In 1811 he arrived in Copenhagen to take up a post at the ruined Church of Our Lady, and in the city his influence and popularity grew.

Like Kierkegaard, Mynster is a cultured, sophisticated thinker and a gifted writer as well as a remarkable preacher; he, too, struggled with his religious upbringing. Yet unlike Kierkegaard, Mynster distinguishes himself by a genius for moderation. His remarkable ability to steer a middle path has not only sustained his broad appeal, but enabled him to embody half a century of Danish Christianity while warding off its excesses. Like the Enlightenment rationalists who still dominate official theology, Mynster is optimistic about human nature: his call to conscience expresses firm faith in human judgement. Like the pietists, he is willing to venture into the emotional depths of human experience and to attend to the spiritual life. Like the Romantics, he finds harmony between God and the natural world. But he avoids the frigidity of rationalism, the fervid tendencies of pietism, the unorthodoxy of Romanticism. And Mynster’s preaching is appreciated by the less as well as the more cultured among his congregation, for he combines intellectual gravitas with a taste for simple, honest faith. He is well versed in the modern German thinkers who put the idea of freedom at the centre of their philosophies – he studied Kant and Schelling before he took his first appointment as a pastor – but his instincts are conservative. He stands – moderately, of course – for order and tradition, for theological orthodoxy and absolute monarchy, arguing that these secure structures are most conducive to individual freedom.

When he gave Kierkegaard his first communion in 1828, Mynster was well into his ascent through the Danish State Church and in sight of its highest rank. During Kierkegaard’s childhood, Mynster had steadily accumulated influence within the ecclesial establishment: he became a director of the Pastoral Seminary and of the Danish Bible Society, and a governor of the University of Copenhagen; he prepared a new edition of Luther’s Small Catechism, used in schools throughout Denmark, and helped to revise the Danish translation of the New Testament. He married the daughter of the Bishop of Zealand, leader of the national Church. In 1826 he was appointed as a preacher to the royal court, and soon afterwards promoted to the prestigious post of chaplain at the Palace Church, ‘the most fashionable place of worship in Copenhagen’. In 1834, following the death of his father-in-law, Mynster became Bishop of Zealand, and the most conspicuous representative of Denmark’s visible Lutheran Church. This high office ordains a silk robe with a velvet front. And the King made him a Knight of the Order of the Dannebrog, which requires him to wear around his neck a solid gold cross, and on his left breast an even larger cross decorated with silver rays, like a star.

Mynster had left his parish for the royal court before the Church of Our Lady finally reopened in the summer of 1829. But like Mynster’s preaching, the new church offered its parishioners a model of modern, enlightened Christianity rooted in biblical tradition. Its architect was Christian Frederik Hansen, renowned for his neoclassical style: he had already designed the imposing courthouse and city hall on Nytorv, next to Kierkegaard’s family home. Hansen rebuilt the church’s porch with six stone pillars, just like the courthouse portico. Both buildings asserted the humanist ideals of ancient Rome – now reclaimed by Protestant Christendom as the bedrock of Enlightenment rationality, the foundation for a universal morality and a stable civic life.

C. F. Hansen’s Church of Our Lady

C. F. Hansen’s Courthouse and City Hall, 1850 (Kierkegaard’s first home, 2 Nytorv, can be seen on the far right)

Kierkegaard was sixteen years old when he entered the Church of Our Lady for the first time, on 12 June 1829, five days after the church was re-dedicated. That morning – it was a Friday – he followed his family through the great pillars into the large, light interior, and looked up at the towering statues of the apostles, six on each side of the nave. There was neither Madonna nor child in this Church of Our Lady. Bertel Thorvaldsen, Scandinavia’s most celebrated sculptor, had amplified Hansen’s classical theme by casting twelve muscular disciples – larger than life-sized, too large for the alcoves Hansen built for them – in the pose of Roman generals, imperiously surveying the congregation. Yet these broad-shouldered men carried symbols of their martyrdom, reminding Kierkegaard of Jesus’s terrifying warning that his followers might have to suffer and die for their faith.

Inside the Church of Our Lady, Copenhagen

And he saw, straight ahead of him, above and behind the altar, the figure of Christ himself. Thorvaldsen had made this statue massive, even bigger than the twelve apostles – yet unlike them, this Christ exuded gentleness and grace. His head was bowed, his arms were outstretched and his hands open, and he stepped forward as if to meet his followers with his vast embrace. Somehow these gestures expressed a deep stillness. His quiet power was astonishing; he drew you in, but also brought you to a halt. On the marble pedestal beneath his feet, in golden relief, were the words KOMMER TIL MIG. Kierkegaard recognized, of course, the verse from Matthew’s Gospel: ‘Come unto me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.’

Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Christus

Since that day, nearly two decades ago now, he has walked through the Church of Our Lady’s grand entrance countless times. As is the custom of most church-going Danes, he attends the weekly Sunday morning service, and takes communion once or twice a year – but on a Friday, when the church is quiet and the congregation small. And each time he enters the Church of Our Lady and walks beneath the lofty gaze of those twelve disciples, as he did this Easter morning, the insistent invitation is repeated: ‘Come unto me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.’

These words sound so sure, so definite: they give a command, and they make a promise. For Luther, it was words like these that expressed the clear certainty of salvation for all the faithful, the hallmark of his new interpretation of the Gospel. Yet for Kierkegaard they contain endless questions – that is to say, the same questions, asked over and over again. Why is mere existence wearying, and what is this heavy burden he continues to carry? Why is being human so difficult for him, when it seems to come easily to others? What kind of rest is he seeking, and why can’t he find it for himself? What does it mean to follow Christ within this world, where most paths seem to lead away from what is true and conducive to peace? Why does Christ seem to be so far away, even after eighteen centuries of Christianity? Has all this preaching, prayer, refinement of doctrine, biblical commentary and ecclesial politics – in a word, the construction of Christendom – brought people closer to God, or cast them further from him? If it must be difficult to follow Christ – and look at those long-suffering apostles! – then who would choose his narrow thorny path, when there are far more comfortable ways to live?

Kierkegaard thinks that Bishop Mynster answers these questions too easily, and therefore hardly answers them at all. Over three hundred years, Luther’s fiery certainty has gradually cooled into complacency: Mynster’s preaching offers a ‘gentle comfort’ which underestimates the myriad, shifting layers of duplicity – self-evasion, self-deception, self-destruction – that shroud the human heart and turn it stubbornly away from God. ‘The truth that divine governance embraces everything which happens on earth can be grasped by every human understanding and felt by every human heart,’ insists Mynster. The Bishop knows that, despite the Gospel’s assurances, people are naturally burdened by anxiety and doubts about God – as he was himself before his spiritual breakthrough – but he believes this burden can be eased by Christ’s promise of forgiveness. Mynster’s sermon on Matthew 11:28 in his thick volume of sermons from 1823, so often read in Kierkegaard’s family home, explained this clearly: when Jesus says, ‘Come unto me, all you who are burdened, and I will give you rest’, he is offering ‘certainty for the doubter, strength for the struggling, comfort for the sorrowful’. If people are honest and humble, the sermon continued, they will understand Christ’s message and receive ‘happiness and blessing’.

Mynster’s comforting words are appealing – yet this very appeal makes them false for Kierkegaard, who has always found Christianity disturbing as well as inviting. And he certainly does not share Mynster’s propensity for moderation: he is drawn to a truth that lies at two opposite extremes at once – and the truth of human experience is often like this. In a single day, even in a single hour, a human being can feel suffering and joy, despair and faith, intense anxiety and profound peace.

This is how Kierkegaard finds truth in Christianity: he does not believe that Christian teaching contains facts, which can now, in the modern age, be confirmed by historians or scientists. He sees in the example of Jesus the dual extremities of human existence that, he feels, constitute his own deepest truth. ‘Though he possessed the blessing, he was like a curse for everyone who came near him … like an affliction for those few who loved him, so that he had to wrench them out into the most terrible decisions, so that for his mother he had to be the sword that pierced her heart, for the disciples a crucified love,’ Kierkegaard wrote in one of the ‘upbuilding discourses’ he published last year. Jesus is a paradox: he urged his followers to be perfect, but he spent his time with sinners and tax collectors; he taught an ideal of purity of heart which demands ceaseless striving and invokes rigorous judgement, but at the same time he manifested a mercy that accepts all things with equal love. Being human is at once a blessing and a curse, Kierkegaard believes – more and more so, the closer we come to God – and Jesus exemplifies this more than anyone.

So while there is wisdom in Mynster’s sermons – a grasp of human feeling, and earnestness about the spiritual life – this never goes far enough. Kierkegaard’s purpose as an author is now the ‘inward deepening of Christianity’. He must deepen his neighbours’ need for God, so that the grace that meets this need becomes all the more powerful and profound: ‘Christianity has been taken in vain, made too mild, so that people have forgotten what grace is. The more rigorous Christianity is, the more grace becomes manifest as grace and not a sort of human sympathy.’ When the Bishop turns the Gospel into mere consolation, Kierkegaard believes that he renders it untrue, makes Christianity too easy, too comfortable, whereas the opposite is needed in this complacent age. In the Church of Our Lady, Thorvaldsen’s welcoming Jesus echoes Mynster’s theology: this serene, powerful figure bears no resemblance to the gaunt, bloody, agonized Christ of medieval devotion, adopted by the Lutheran pietists. Yet Kierkegaard hears in his words the pietist insistence on following Christ – for he does not say ‘Admire me’ or ‘Observe me’ or even ‘Worship me’, but ‘Come unto me.’

When his Christian Discourses comes out, three days from now, Copenhageners will be ‘awakened’ from the ‘soothing security’ embodied in their solid cathedral church and in their Bishop’s reassuring sermons. Some of the book’s twenty-eight discourses are situated in the Church of Our Lady, and one considers a verse from Ecclesiastes, ‘Watch your step when you go to the house of the Lord.’ It begins by evoking the calm stillness embodied in Thorvaldsen’s painstakingly carved statues and in the patiently embroidered velvet adorning the pulpit, before exclaiming ‘How quieting, how soothing – alas, and how much danger in this security!’ Religiously, we all need ‘awakening’, but the preaching in this church will ‘lull us to sleep’. Indeed, it seems deliberately designed for ‘tranquillization’. Christian Discourses is, by contrast, an ‘attack’, an assault on its reader’s spiritual senses. Those who go to Christ will find rest – but first they must wake up, move, change their hearts. And who knows where the path that follows Christ will lead, before the promised rest is found?

Since 1843 Kierkegaard has regularly published collections of two, three or four sermons, though he calls them ‘upbuilding discourses’. These discourses are a genre of spiritual writing partly inspired by Moravian preaching: they address each reader privately, and disavow any ecclesial authority. Yet by naming his new sermons Christian Discourses, and setting many of them, theatrically, inside the Church of Our Lady, Kierkegaard is taking a bold step onto Bishop Mynster’s territory. The last seven discourses in the book are written as if for Friday communion services in the church, when a short sermon is always preached before the bread and wine are offered. The communion discourse is becoming Kierkegaard’s favourite genre: he returns to it continually, and each time he writes a new one he pushes his authorship into the heart of the church, addressing Christians as they prepare to draw close to God.

And this is not merely an imaginative act. Last summer, Kierkegaard delivered two of his Friday communion discourses in the Church of Our Lady. On the first occasion he preached on Matthew 11:28, the verse inscribed below Thorvaldsen’s statue of Christ behind the altar, and as he spoke he drew his listeners’ attention to this figure: ‘See, he stretches out his arms and says: Come here, come here unto me, all you who labour and are burdened.’ There were around thirty people taking communion in the church that morning, among them a retired butcher, a nightwatchman, a theology student, a sailor and his wife, an ironsmith, a state councillor, and the widow of an alehouse keeper and her daughter. The ‘labour’ Jesus speaks of, Kierkegaard explained to them, is the ‘longing for God’ that brought them into the church. Then he talked about how hard it is to suffer without being understood. This is one of the great human burdens, he said, which can only be relieved by Christ: ‘I do not know what in particular troubles you, my listeners; perhaps I would not understand your sorrow either or know how to speak about it with insight. But Christ has experienced all human sorrow more grievously than any human being … He not only understands all your sorrow better than you understand it yourself, but he wants to take the burden from you and give you rest for your souls.’

Although that was the first time Kierkegaard had delivered one of his discourses to a church congregation, his voice was well practised: when he composes his works, he reads his sentences aloud, often many times, to sound out their rhythm and melody. He spends hours like this, ‘like a flautist entertaining himself with his flute’, and during these hours he falls ‘in love with the sound of language – that is, when it resounds with the pregnancy of thought’. For a few minutes, those thirty Copenhageners gathered for Friday communion in the Church of Our Lady found themselves admitted into this private world. One man who heard Kierkegaard preach was struck by his ‘exceedingly weak but wonderfully expressive voice’; he had never heard a voice ‘so capable of modulating expression, even the most delicate nuances’, and he felt that he would never forget it.

A few weeks later, in August 1847, Kierkegaard preached a second time in the Church of Our Lady. Again he spoke of the ‘heartfelt longing’ for God that had drawn his listeners into church; he believes that going to Mass should not abate this longing, but only deepen and intensify it. In that sermon he reflected on the practice of Friday communion, his own custom ever since he first received communion from Mynster in 1828. Friday used to be a quiet day in Copenhagen, a day of prayer, but secular routines have gradually taken over traditional religious observance, and taking communion on Fridays now goes against the flow of life on the streets, where people are working, selling and shopping as on other weekdays. These Friday services are much smaller and more intimate than the Sunday Mass, which Kierkegaard always leaves before the communion ritual begins. When he attends church on a Sunday he goes along with the crowd; on a Friday, he can go to the Church of Our Lady ‘openly before everyone’s eyes, and yet secretly, as a stranger, in the midst of all those many people’. And inside the church, ‘the noise of the daily activity of life out there sounds almost audibly within this vaulted space, where this sacred stillness is therefore even greater.’

Kierkegaard’s way of going to communion – in view of the crowd yet surreptitiously, like a secret agent – sums up his way of being a Christian. Following this half-concealed path, he struggles to preserve his ‘inner need’ for God from the conventional dictates of custom and obligation. Remaining a ‘single individual’ within the religious structures offered by the world is such a fine and complex balancing act that it sometimes seems impossible. Last year, he considered dedicating a collection of his Friday communion discourses to Bishop Mynster – ‘with my father in mind I would very much like to do it’ – but eventually, his attitude towards the Bishop divided between reverence and scorn, he concluded that ‘my course in life is too doubtful for me to be able to dedicate my work to any living person’. He was by then uncertain whether he would ‘enjoy honour and esteem, or be insulted and persecuted’ for his writing. And he has ‘never been closer to stopping being an author’ than now, at Easter 1848, with his Christian Discourses.

‘Let us pay tribute to Bishop Mynster,’ Kierkegaard wrote in his journal last year. ‘I have admired no one, no living person, except Bishop Mynster, and it is always a joy to me to be reminded of my father. His position is such that I see the irregularities very well, more clearly than anyone who has attacked him … There is an ambivalence in his life that cannot be avoided, because the “state Church” is an ambivalence.’ Of course, there is also deep ambivalence in Kierkegaard’s admiration for the Bishop, whom he associates so closely with his father.

As he finds the comfortable worldliness of the Danish Church increasingly intolerable, his question of how to live in the world is becoming more entangled with his relationship with this Church, and with Mynster. The Moravian pietists sought holiness by withdrawing from the world: they created enclaves, like Christiansfeld, that were not so different from monastic enclosures, and formed their own congregations outside the State Church – though many Danes, like Kierkegaard’s father, moved easily between the Moravian meeting house and their parish church. Kierkegaard has heard pastors defend the worldly character of their Church by pointing out that Jesus himself did not enter a monastery, or go and live in the desert. But he thinks that, for Jesus, becoming a monk or a hermit was a temptation – for what a relief it would have been to leave the suspicious, uncomprehending crowds! – while being in the world was an act of renunciation. Jesus did not stay in the world ‘to become a councillor of justice, a member of a knightly order, an honorary member of this or that society, but in order to suffer’.

And Kierkegaard is coming to understand his own life in this way too. Becoming a writer has in one sense set him apart from civic life: in 1841 this was, for him, the clear alternative to marrying Regine and entering a profession. Yet his writings have confronted the world and demanded its attention. He has made himself conspicuous on the streets of Copenhagen, in the local press, within the city’s literary and intellectual circles, and he has subjected himself to their judgements on his life as well as on his work. Being a writer like this is no retreat from the world; this is why he has been continually tempted to stop writing, and perhaps it is also why he feels he cannot stop now. Being a recluse would be too easy, he tells himself, as he hurries home to his pen, ink and paper. Now he wonders whether he should make himself more prominent within the Church, gain greater influence there, in order to provoke it into truthfulness from within.

Just as he feels his own existence stretched between greater extremes of suffering and fulfilment, pulling him almost to breaking point, so he is trying to stretch Christianity in both these directions, in order to deepen it. Like the Moravian preachers he used to hear at the meeting house on Stormgade, he emphasizes Jesus’s suffering. But he thinks less of the bloody crucifixion than of the inward torment of living among people who could not understand the extraordinary man who tried to teach them to encounter God. He feels that he, too, is suffering in a world where he is misunderstood; he wonders whether Jesus wants his followers ‘to become just as wretched as he was, before the consolation comes’.

And he does believe that consolation will come – though only on the far side of pain and trial. He is convinced that faith must neither avoid suffering nor drown in it, but move through it to find joy. Even now, this bright Easter day, after everything that has happened to him, he considers himself ‘an extremely unhappy man, who nevertheless, by the help of God, is indescribably blessed’.